mardi, 24 septembre 2013

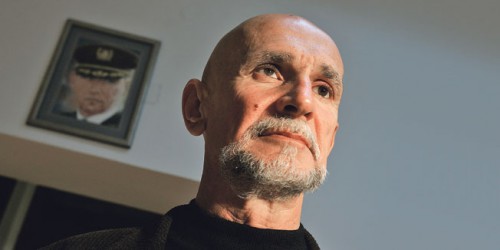

Zvonko Busic, un suicide pour le salut de la Croatie et de l’Europe

In memoriam

Zvonko Busic, un suicide pour le salut de la Croatie et de l’Europe

par Jure Georges VUJIC

Trois mois seulement après la mort tragique de Dominique Venner, un autre suicide sacrificiel a retenti au matin du 1er septembre, non sous le Soleil de Paris au cœur de Notre-Dame, mais cette fois-ci en Croatie à Rovanjska sur le littoral croate de l’Adriatique. C’est le suicide de Zvonko Busic, l’un des derniers dissidents et révolutionnaires croates de l’époque yougoslave communiste.

Busic venait de purger une peine de trente-deux ans de prison pour avoir détourné pour des raisons politiques (la cause de l’indépendance croate) en 1976 un avion étatsunien. Il fut libéré en 2008. Son retour en Croatie suscita un accueil triomphal de la part d’une grande partie de la population croate. En 1976, il avait dirigé un groupe de révolutionnaires et nationalistes croates qui détourna un Boeing 727 de la compagnie T.W.A. sur un vol New York – Chicago avec soixante-seize passagers à bord afin d’attirer l’attention du monde sur la lutte indépendantiste croate désireuse de se séparer de la Yougoslavie communiste et titiste… L’avion s’était finalement posé à Paris et la presse étatsunienne avait publié leur revendication. Mais un policier à New York avait été tué en tentant de désamorcer une bombe que les pirates de l’air avaient dissimulé dans une station de métro. Condamné par les autorités américaines sous la pression de Belgrade à la prison á vie, il fut amnistié pour conduite exemplaire. Alors qu’il avait retrouvé de retour en Croatie son épouse Julienne Eden Busic, de citoyenneté étatsunienne qui l’avait secondé dans sa prise d’otage (elle avait été libérée en 1990), il décida de poursuivre la lutte politique dans sa patrie qui, après avoir gagné la guerre d’indépendance en 1991, est plongé dans le marasme politique, économique et moral par la responsabilité des gouvernements successifs néo-communistes et mondialistes. Ils ont livré la Croatie aux magouilles politico-affairistes, au Diktat des eurocrates de Bruxelles et de leurs laquais locaux ainsi qu’à la convoitise des oligarchies anti-nationales. Toutes s’efforcent de faire table rase de l’identité nationale croate en imposant comme d’ailleurs partout en Europe, le sacro-saint modèle néo-libéral, des lois liberticides, la propagande du gender à l’école, la légalisation du mariage homosexuel. Bref, le scénario classique de l’idéologie dominante et mondialiste. Busic qui aimait citer Oswald Spengler n’était pas homme à accepter cet état de fait qu’il qualifiait lui-même de « déliquescence morale et sociale catastrophique ».

Busic soutint toutes les luttes révolutionnaires et nationales, de l’O.L.P. palestinien à l’I.R.A. irlandaise en passant par les Indiens d’Amérique du Nord. Ironie de l’histoire, il avait découvert les écrits historique de Dominique Venner en prison et fut peiné par sa disparition tragique.

Homme « classique » épris des vertus de l’Antiquité, Busic était avant tout un résistant croate et européen, un baroudeur qui n’avait que du mépris pour le conformisme, la tricherie, la petite politique partisane et parlementaire, les calculs électoraux. Son idéal type était évolien : le moine-soldat, un style sobre et austère, guerrier, un genre de vie qu’il a appliqué durant toute sa vie. Ce n’est pas par hasard qu’il fut très vite marginalisé par le système politique croate qu’il soit de droite ou de gauche. Après avoir rallié fort brièvement le Parti du droit croate (H.S.P.) du Dr. Ante Starcevic et de l’actuelle députée croate au Parlement européen, Ruza Tomasic, il tenta, en fondant l’association Le Flambeau, de constituer un « front national » regroupant l’ensemble des forces nationales croates (droite et gauche confondues). Mais très vite, cette vision et ce projet frontiste, d’orientation nationale-révolutionnaire, se soldèrent par un échec en raison des luttes de pouvoir inhérentes à la mouvance nationale croate. Busic n’avait pas caché sa déception en déclarant qu’« il n’avait pas réussi dans l’unification et la création d’un front uni patriotique ». Il annonça alors dans la presse croate sa décision de se retirer de la politique, car « il ne voulait pas contribuer à la destruction continue des forces politiques nationales et patriotiques en Croatie ».

Les obsèques de Zvonko Busic auxquels ont assisté des milliers de personnes et l’ensemble de la mouvance nationale croate, constituèrent (à Zagreb le 4 septembre dernier) furent un sérieux avertissement à la classe politique mondialiste croate. Son suicide fut un événement sans précédent pour l’opinion croate, habituée à ses coups de de colère, son franc parler et son idéalisme infatigable face à l’apathie sociale et la corruption de classe politique. Il faut dire qu’il a été longtemps traîné dans la boue par la presse croate gauchisante qu’il l’a continuellement traité de terroriste dès sa sortie de prison. Personne, et encore moins moi-même qui l’avait régulièrement côtoyé, ne s’était attendu à la fin tragique, de cet homme d’action à l’allure légionnaire et don quichottesque. Et après tout, est-ce que quelqu’un avait pu s’attendre au suicide de Dominique Venner ? Probablement non. Peu avant sa mort, Zvonko Busic a laissé une lettre à son ami Drazen Budisa, dans laquelle il avait demandé pardon á ses proches et qu’il se retirait car « il ne pouvait plus continuer de vivre dans l’obscurité de la Caverne platonicienne », faisant allusion à l’allégorie platonicienne de la Caverne. C’est vrai. Busic était trop pur, trop droit et trop sensible pour vivre dans le mensonge de cette Croatie post-communiste néo-libérale hyper-réelle, une Croatie qui avait fait allégeance à l’U.E. et à l’O.T.A.N., domestiquée et néo-titiste, alors que le gouvernement actuel refuse de livrer aux autorités allemandes, Josip Perkovic, qui fait l’objet d’un mandat d’extradition européen. Cet ancien agent de l’U.D.B.A. (la police politique et services secrets titiste yougoslaves) est impliqué dans l’assassinat de plusieurs dissidents croates à l’étranger.

La Croatie est le seul pays post-communiste à ne pas avoir voté une loi sur la lustration et où les rênes du pouvoir politique et économique sont encore entre les mains des anciens cadres titistes et de la police secrète qui n’a jamais été officiellement démantelée. Busic – c’est vrai – ne pouvait supporter ces ombres factices et éphémères de la société marchande et consumériste mondiale, à l’égard de laquelle il s’est tant offusqué. Et pourtant, Busic, tout comme Venner, est tombé, volontairement, froidement, consciemment, je dirai même sereinement. Comme pour Venner, il s’agit du même modus operandi, du même esprit sacrificiel, d’une mort annoncée, une mors triumfalis qui dérange et interroge. Dans le cas de la Croatie, sa mort a retenti non comme une fin, mais comme un avertissement, un appel à la mobilisation, un dernier appel à la lutte, un dernier sursaut pour le salut de la nation croate et européenne. Puisse ses vœux être exhaussés !

Jure Georges Vujic

Article printed from Europe Maxima: http://www.europemaxima.com

URL to article: http://www.europemaxima.com/?p=3415

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Hommages | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : politique internationale, croatie, mitteleuropa, europe, affaires européennes, hommage, zvonko busic, mort volontaire, politique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

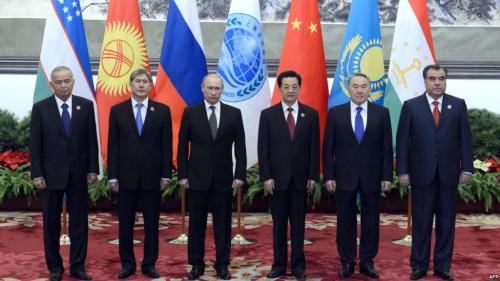

Shanghai Cooperation Organisation warns against US-led war on Syria

Shanghai Cooperation Organisation warns against US-led war on Syria

By John Chan

Ex: http://www.wsws.org/

The latest summit of the Russian- and Chinese-led Central Asian grouping, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), held in Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan, on September 13, was dominated by the rising global tensions produced by the US preparations for war against Syria.

Russian President Vladimir Putin insisted that “military interference from outside the country without a UN Security Council sanction is inadmissible.” The summit’s joint declaration opposed “Western intervention in Syria, as well as the loosening of the internal and regional stability in the Middle East.” The SCO called for an international “reconciliation” conference to permit negotiations between the Syrian government and opposition forces.

As he had done at the recent G20 summit in St Petersburg, Chinese President Xi Jinping lined up with Russia against any military assault on Damascus, fearing that it would be a prelude to attack Iran, one of China’s major oil suppliers.

Significantly, Iran’s new President Hassan Rouhani attended the meeting, despite suggestions that his government would mark a shift from former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and his anti-American rhetoric at previous SCO summits. Rouhani welcomed Russia’s proposal to put Syria’s chemical weapons under international control, claiming that it has “given us hope that we will be able to avoid a new war in the region.”

The SCO explicitly supported Iran’s right to develop its nuclear program. Putin insisted in an address that “Iran, the same as any other state, has the right to peaceful use of atomic energy, including [uranium] enrichment operations.” The SCO declaration warned, without naming the US and its allies, that “the threat of military force and unilateral sanctions against the independent state of [Iran] are unacceptable.” A confrontation against Iran would bring “untold damage” to the region and the world at large.

The SCO statement also criticised Washington’s building of anti-ballistic missile defence systems in Eastern Europe and Asia, aimed at undermining the nuclear strike capacity of China and Russia. “You cannot provide for your own security at the expense of others,” the statement declared.

Despite such critical language, neither Putin nor Xi want to openly confront Washington and its European allies. Prior to the SCO summit, there was speculation that Putin would deliver advanced S-300 surface-to-air missile systems to Iran and build a second nuclear reactor for the country. Russian officials eventually denied the reports.

Russia and China are facing growing pressure from US imperialism, including the threat that it will use its military might to dominate the key energy reserves in the Middle East and Central Asia. The SCO was established in 2001, shortly before the US utilised the “war on terror” to invade Afghanistan. Although the SCO’s official aim is to counter “three evils”—separatism, extremism and terrorism in the region—it is above all a bid to ensure that Eurasia does not fall completely into Washington’s orbit.

Apart from the four former Soviet Central Asian republics—Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan—the group also includes, as observer states, Mongolia, Iran, India, Pakistan and Afghanistan. The “dialogue partners” are Belarus, Sri Lanka and, significantly, Turkey, a NATO member, which was added last year.

However, US influence is clearly being brought to bear on the grouping. Before the summit, there were reports in the Pakistani press that the country could be accepted as a full SCO member. Russia invited new Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif to attend. However, Sharif only sent his national security advisor Sartaj Aziz, and no Pakistan membership was granted.

While the SCO is looking to enhance its role in Pakistan’s neighbour, Afghanistan, after the scheduled withdrawal of NATO forces, Aziz said Pakistan’s policy was “no interference and no favorites.” He insisted that the US-backed regime in Kabul could achieve an “Afghan-led reconciliation” if all countries in the region resisted the temptation to “fill the power vacuum.”

China and Russia are also deeply concerned by the US “pivot to Asia” to militarily threaten China and to lesser extent, Russia’s Far East, by strengthening Washington’s military capacities and alliances with countries such as Japan and South Korea. In June, China and Russia held a major joint naval exercise in the Sea of Japan, and in August, they carried out joint land/air drills in Russia involving tanks, heavy artillery and warplanes.

Facing US threats to its interests in the Middle East and the Asia-Pacific, China is escalating its efforts to acquire energy supplies in Central Asia. For President Xi, the SCO summit was the last stop in a 10-day trip to Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan—where he signed or inaugurated multi-billion-dollar deals for oil and gas projects.

At his first stop, Turkmenistan, Xi inaugurated a gas-processing facility at a massive new field on the border with Afghanistan. Beijing has lent Turkmenistan $US8 billion for the project, which will triple gas supplies to China by the end of this decade. The country is already China’s largest supplier of gas, thanks to a 1,800-kilometer pipeline across Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan to China.

In Kazakhstan, where Xi signed a deal to buy to a minority stake in an offshore oilfield for $5 billion, he called for the development of a new “silk road economic belt.” Trade between China and the five Central Asian republics has increased nearly 100-fold since 1992, and Kazakhstan is now the third largest destination of Chinese overseas investment.

Xi delivered a speech declaring that Beijing would never interfere in the domestic affairs of the Central Asian states, never seek a dominant role in the region and never try to “nurture a sphere of influence.” This message clearly sought to also placate concerns in Russia over China’s growing clout in the former Soviet republics.

During the G20 summit, the China National Petroleum Corporation signed a “basic conditions” agreement with Russia’s Gazprom to prepare a deal, expected to be inked next year, for Gazprom to supply at least 38 billion cubic metres of gas per year to China via a pipeline by 2018.

With so much at stake, Wang Haiyun of Shanghai University declared in the Global Times that “maintaining regime security has become the utmost concern for SCO Central Asian members, including even Russia.” He accused the US and other Western powers of inciting “democratic turmoil” and “colour revolutions” and warned that if any SCO member “became a pro-Western state, it will have an impact on the very existence of the SCO.” If necessary, China had to show “decisiveness and responsibility” to join Russia and other members to contain the turmoil, i.e. to militarily crush any “colour revolution” in the region.

The discussions at the SCO meeting are a clear indication that Russia and China regard the US war plans against Syria and Iran as part of a wider design to undermine their security, underscoring the danger that the reckless US drive to intervene against Syria will provoke a far wider conflagration.

Copyright © 1998-2013 World Socialist Web Site - All rights reserved

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Eurasisme, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : politique internationale, géopolitique, sco, chine, russie, inde, brics, syrie, levant, moyen orient, proche orient |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Dette abyssale : pourquoi ?

Dette abyssale : pourquoi ? Que risque-t-il de se passer ?

par Guillaume Faye

Ex: http://www.gfaye.com

La dette souveraine française va bientôt atteindre les 2000 milliards d’euros, c’est-à-dire 95,1% du PIB fin 2014, soit 30.000 € par Français. Bombe à retardement. Il y a dix ans, elle atteignait 1.000 milliards et l’on criait déjà à la catastrophe. Mais personne n’a rien fait. Depuis 1974 ( !) aucun budget n’a été en équilibre : tous déficitaires. Les multiples rapports, comme ceux de la Cour des Comptes, ont tous été jetés au panier. Chaque année, il faut rembourser 50 milliards d’euros d’intérêts, deuxième budget de l’État.

Mais pourquoi s’endette-t-on ? Certainement pas pour investir (et donc pouvoir rembourser par les gains escomptés) (1), mais pour les raisons suivantes : A) Payer une fonction publique pléthorique et surnuméraire, qui ne cesse d’enfler. B) Régler les prestations sociales d’un État Providence qui suit (droite et gauche confondues) les préceptes absurdes du collectivisme (2). Parmi ces prestations, on note les allocations chômage les plus généreuses au monde qui, paradoxalement, provoquent l’accroissement du chômage et dissuadent les embauches ; le coût croissant des allocations aux immigrés d’origine et aux étrangers les plus divers, y compris clandestins et fraudeurs (type AME), pris en charge comme nulle part ailleurs au monde ; l’absurdité totale des emplois aidés – pour les mêmes populations – qui ne créent aucune valeur ajoutée. C) L’endettement sert aussi à payer les intérêts de la dette ! Absurdité économique totale, qui ne choque pas la cervelle de nos énarques. On creuse un trou pour en boucher (sans succès d’ailleurs) un autre.(3)

L’Allemagne, elle, a rééquilibré son budget et voit décroître sa dette. Elle mène une politique d’austérité d’expansion, incompréhensible pour les dirigeants français, incapables d’envisager le moindre effort et abonnés au déni de réalité. Et, contrairement à une certaine propagande, pas du tout au prix d’une paupérisation de la société par rapport à la France. Je parlerai du cas de l’Allemagne dans un prochain article. Maintenant, quels risques majeurs font courir à la France cet endettement colossal et croissant (4) ?

A) L’agence France Trésor qui emprunte actuellement à taux bas va automatiquement se voir imposer très bientôt des taux à plus de 5%. Donc on ne pourra plus emprunter autant. B) Il semble évident que, si l’on peut encore rembourser les intérêts, on ne pourra jamais rembourser le ”principal”, même en 100 ans. Point très grave. Un peu comme les emprunts russes d’avant 1914. C) Cette situation aboutira à la ”faillite souveraine”, avec pour conséquence l’effondrement mécanique, brutal et massif, de toutes les prestations sociales de l’État Providence, des salaires des fonctionnaires, des pensions de retraite, etc. D) La France sera donc soumise au bon vouloir de ses créanciers et contrainte de solliciter l’aide d’urgence du FMI, de la BCE et, partant de l’Allemagne, voire de la Fed américaine… Indépendance nationale au niveau zéro, mise sous tutelle. (5) E) Une position débitrice insolvable de la France, seconde économie européenne, provoquera un choc économique international d’ampleur lourde – rien à voir avec la Grèce. F) Paupérisation et déclassement dans tous les domaines : plus question d’entretenir les lignes SNCF ou d’investir dans la recherche et les budgets militaires, etc. G) Enfin, surtout avec des masses d’allogènes entretenues et qu’on ne pourra plus entretenir, cette situation pourra déboucher sur une explosion intérieure qu’on n’a encore jamais imaginée – sauf votre serviteur et quelques autres.

Et encore, on n’a pas mentionné ici la dette de la Sécurité sociale et celles des collectivités locales, en proie à une gestion dispendieuse, irresponsable, incompétente. L’impôt ne pourra plus rien compenser car il a largement atteint son seuil marginal d’inversion de rendement. Mais enfin, le mariage des homos, la punition contre le régime syrien, la suppression des peines de prison pour les criminels, ne sont-ils pas des sujets nettement plus urgents et intéressants ? Un ami russe, membre de l’Académie des Sciences de son pays, me disait récemment, à Moscou : « je ne comprends plus votre chère nation. Vous n’êtes pas dirigés par des despotes, mais par des fous ».

(1) Depuis Colbert jusqu’aux enseignements basiques de toutes les écoles de commerce, on sait qu’un endettement ne peut être que d’investissement et surtout pas de fonctionnement ou de consommation. Qu’il s’agisse d’entreprises, de ménages, de communes, de régions ou d’États. Autrement, on ne pourra jamais le rembourser et ce sera la faillite. Une célèbre Fable de La Fontaine l’avait expliqué aux enfants : La cigale et la fourmi. La fourmi refuse de lui prêter pour consommer pendant l’hiver car elle sait qu’elle ne sera jamais remboursée puisque la cigale chante gratuitement et ne travaille pas. En revanche, si la cigale lui avait demandé un prêt pour organiser une tournée de chant payante, la fourmi aurait accepté. Logique économique basique, hors idéologie.

(2) Le collectivisme peut fonctionner plusieurs décennies dans une économie entièrement socialisée, sans secteur privé, comme on l’a vu en URSS et dans le défunt ”bloc socialiste”. Au prix, évidemment, d’un système de troc autarcique. Pourquoi pas ? Mais l’expérience (plus forte que les idées pures des idéologues) a démontré que ce système est hyperfragile sur la durée car il nécessite un système politique pyramidal et de forte contrainte, et provoque une austérité générale que les populations ne supportent pas objectivement, en dépit de tous les discours et utopies des intellectuels. Mais l’aberration française, c’est d’entretenir un système intérieur collectiviste dans un environnement européen et international mercantile et ouvert. Du socialisme à l’échelle d’un petit pays dans un énorme écosystème libéral. Cette contradiction est fatale : c’est un oxymore économique. Ça ne pourra pas durer. L’énorme Chine elle, peut surmonter ce paradoxe : un régime pseudo-communiste, anti-collectiviste, mais animé par un capitalisme d’État. Mais c’est la Chine…Inclassable.

(3) Aberration supplémentaire: la France s’endette pour prêter aux pays du sud de l’UE endettés afin qu’ils puissent payer les intérêts de leur dette ! On creuse des trous les uns derrière les autres pour pouvoir reboucher le précédent. Le « Plan de soutien financier à la zone euro » à augmenté la dette française de 48 milliards d’euros et culminera en cumulé à 68,7 milliards en 2014. Emprunter pour rembourser ses dettes ou celles de ses amis, ou, pire les intérêts desdites dettes, cela à un nom : la cavalerie.

(4) Contrairement à qu’on entend un peu partout, la dette ne peut que croître en volume principal, même si le déficit passe en dessous du chiffre pseudo-vertueux des 3% négocié avec Bruxelles. La créance brute ne décroît que si le budget du débiteur est définitivement à l’équilibre, voire excédentaire, pendant plusieurs années – et encore cet excédent doit-il est majoré en fonction des taux d’intérêt. Arithmétique de base, qu’on n’enseigne probablement pas à l’ENA.

(5) La solution du Front national – sortir de l’Euro, reprendre le Franc, retrouver une politique monétaire indépendante, pouvoir dévaluer (bon pour l’exportation), pouvoir faire fonctionner la planche à billets librement comme la Fed, s’endetter par des émissions auprès de la Banque de France et non plus des marchés – est irréaliste. Pour deux raisons techniques : d’abord parce que l’économie française n’a pas la taille mondiale de l’économie américaine qui est en situation de ”monétarisation autonome” (self money decision) ; ensuite, et pour cette raison, parce qu’une telle politique, même si elle ferait baisser la charge de la dette, aurait pour conséquence mécanique un effondrement de l’épargne et des avoirs fiduciaires des Français, en termes non pas nominaux mais marchands. ”Vous aviez 100.000 € en banque, le mois dernier, avant le retour au Franc ? En compte courant, assurance vie, épargne populaire, etc ? Désolé, en Francs, il ne vous reste plus que l’équivalent de 50.000.” Politiquement dévastateur. La seule solution (voir mon essai Mon Programme, Éd. du Lore) est de bouleverser le fonctionnement de la BCE, dont l’indépendance est une hérésie, et d’envisager une dévaluation de l’Euro.

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Economie, Nouvelle Droite, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : guillaume faye, nouvelle droite, économie, dette, france, europe, affaires européennes, politique internationale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

A 70 años de la muerte de Simone Weil

Mailer Mattié*

Instituto Simone Weil/CEPRID

Ex: http://paginatransversal.wordpress.comEl 18 de julio de 1943, un mes antes de morir, Simone Weil escribió desde Londres a sus padres que se encontraban en Nueva York:

Tengo una especie de certeza interior creciente de que hay en mí un depósito de oro puro que es para transmitirlo. Pero la experiencia y la observación de mis contemporáneos me persuade cada vez más de que no hay nadie para recibirlo. Es un bloque macizo. Lo que se añade se hace bloque con el resto. A medida que crece el bloque, deviene más compacto. No puedo distribuirlo en trocitos pequeños. Para recibirlo haría falta un esfuerzo. Y un esfuerzo ¡es tan cansado!

Aquí Weil señala tres requisitos a su parecer imprescindibles para acercarse a la comprensión de su pensamiento: ese bloque compacto de oro puro. Ciertamente, es necesario un importante esfuerzo intelectual el cual, sin embargo, resultaría del todo insuficiente si no podemos acceder a la verdad sobre el mundo social en el que vivimos y si no contamos con determinadas experiencias; es decir, con determinadas referencias de aprendizaje.

¿A qué se refería en realidad Simone Weil? ¿Qué era aquello que impedía a sus contemporáneos comprender sus propuestas?

Con gran probabilidad, es posible que aludiera a dos de los rasgos que caracterizan la existencia humana en la sociedad moderna: ignorar la experiencia histórica que constituye el pasado y aceptar la distorsión del conocimiento que creemos tener sobre la realidad. El pasado, en efecto, ha sido borrado por el progreso, arrasado por el desarrollo del Estado y de la economía, destruido por la industrialización. Las ideologías y el pensamiento académico, por otra parte, han secuestrado la verdad al adscribirla a los dogmas heredados del siglo XIX.

Sería legítimo, entonces, preguntarnos sobre nuestras propias posibilidades de llegar a contar al menos en parte con esas referencias, puesto que ahora nos encontramos en disposición de dar testimonio real de los errores y el fracaso de las formas de organización social sustentadas en las ideologías del progreso económico. Somos testigos desde finales del siglo pasado, además, de la determinación y autonomía de la emergencia de la invalorable riqueza de saberes –que apenas la ciencia está comenzando a validar- contenida en las antiguas culturas y cosmovisiones de muchos pueblos originarios, sobrevivientes del exterminio en los territorios andinos o amazónicos, por ejemplo.

Asimismo, nos devuelven la verdad del pasado los recientes –aunque aún escasos- estudios que intentan revelar la realidad social que constituyó la Alta Edad Media en Europa, oculta en la falsa e interesada definición del Feudalismo y en la interpretación lineal que simplifica la historia, entre los cuales podemos destacar la obra del filósofo e historiador Félix Rodrigo Mora en referencia a la península Ibérica: Tiempo, Historia y Sublimidad en el Románico Rural, publicada en 2012. La crisis de las ideologías, por otra parte, anima el verdadero conocimiento, incluyendo la recuperación del pensamiento de autores importantes que fueron condenados al olvido porque sus criterios comprometían seriamente la solidez de las ideas dominantes. Es el caso, por ejemplo, de la obra de Silvio Gesell escrita a principios del siglo XX sobre la función del dinero en los sistemas económicos y el lugar que la moneda podría desempeñar en un proceso de transformación social. Planteamiento que ha servido de inspiración al matemático estadounidense Charles Eisenstein para proponer una transición hacia la economía del don en su libro Sacred Economics. Gift and Society in the Age of Transition, publicado en 2010.

Simone Weil fue, ciertamente, una tenaz observadora del mundo social, cualidad que la condujo siempre a desconfiar de las teorías y de las interpretaciones a priori. Una actitud, además, que contribuyó indudablemente a impregnar su corta vida de la intensidad que nos asombra. Exploró también el pasado, al encontrar absurdo enfrentarlo al porvenir. Halló así en la experiencia histórica que había constituido la sociedad occitana del sur de Francia en el siglo XIII –destruida sin piedad por la fuerza incipiente del Estado- los fundamentos para elaborar el núcleo de lo que sería su gran obra, Echar Raíces: la noción de las necesidades terrenales del cuerpo y del alma. A la luz de la mirada occitana, en efecto, advirtió el júbilo de la vida convivencial, basada en la obediencia voluntaria a jerarquías legítimas (no al Estado, cuya autoridad aunque sea legal no es necesariamente legítima) y en la satisfacción de las necesidades vitales. Un espacio colectivo que encuentra su justo equilibrio en la estrategia que consiste en juntar los contrarios -libertad y subordinación consentida, castigo y honor, soledad y vida social, trabajo individual y colectivo, propiedad común y personal-, para sustentar así el arraigo de las personas en un territorio, en la cultura, en la comunidad. Es lo mismo que el pueblo kichwa y el pueblo aymara llaman Sumak Kawsay o Suma Qamaña –el Buen Vivir que es convivir-; eso que el pueblo mapuche nombra Kyme Mogen y el pueblo guaraní Teko Kaui, siguiendo el mandato original de construir la tierra sin mal; en fin, aquello que para los pueblos amazónicos significa Volver a la Maloca, valorando el saber ancestral: es decir, regresar a la complementariedad comunitaria donde lo individual emerge en equilibrio con la colectividad; a la vida en armonía con los ciclos de la naturaleza y del cosmos; a la autosuficiencia; a la paz y a la reciprocidad entre lo sagrado y lo terrenal.

Simone Weil, por tanto, consideró la destrucción del pasado el mayor de los crímenes.

En ausencia de convivencialidad, al contrario, Weil observó que la sociedad se convierte en el reino de la fuerza y de la necesidad. Cuando la sociedad es el mal, cuando la puerta está cerrada al bien –afirmó-, el mundo se torna inhabitable. Los medios que deberían servir a la satisfacción de las necesidades se han transformado en fines, tal como sucede con la economía, con el sistema político, con la educación, con la medicina y con la alimentación industrial. Si esta metamorfosis ha tenido lugar, entonces en la sociedad impera la necesidad.

Una realidad que nos impone, en consecuencia, la obligación absoluta y universal como seres sociales de intentar limitar el mal. Es decir, la obligación absoluta de amar, desear y crear medios orientados a la satisfacción de las necesidades humanas. Medios –según Weil- que solo pueden ser creados a través de lo espiritual, de aquello que ella misma llamó sobrenatural: solo a través del orden divino del universo puede el ser humano impedir que la sociedad lo destruya. En la sociedad moderna –expresó- el orgullo por la técnica –por el progreso- ha permitido olvidar que existe un orden divino del universo.

En ausencia de espiritualidad –afirmó-, no es posible construir una sociedad que impida la destrucción del alma humana.

Lo espiritual en Weil –algo que siempre parece tan difícil de precisar-, la fuente de luz, lo que debería guiar nuestra conducta social, representa la diferencia entre el comportamiento humano y el comportamiento animal: una diferencia infinitamente pequeña que es, no obstante, una condición de nuestra inteligencia -en espera aún de rigurosa definición científica que la concrete-. El papel de lo infinitamente pequeño es infinitamente grande, señaló en una oportunidad Louis Pasteur.

Es a partir de la influencia de esta ínfima diferencia, entones, que es posible limitar el mal en la sociedad, porque esa condición de nuestra inteligencia es justamente la fuente del bien: es decir, es la fuente de la belleza, de la verdad, de la justicia, de la legitimidad y lo que nos permite subordinar la vida a las obligaciones. La misma influencia, pues, que debemos explorar en la experiencia del pasado: en el medioevo cristiano –señaló Weil-, pero también en todas aquellas civilizaciones donde lo espiritual ha ocupado un lugar central y hacia donde toda la vida social se orientaba. Precisar sus manifestaciones concretas, sus metaxu: los bienes que satisfacen nuestras necesidades e imprimen júbilo a la vida social.

*Mailer Mattié es economista y escritora. Este artículo es una colaboración para el Instituto Simone Weil de Valle de Bravo en México y el CEPRID de Madrid.

Fuente: CEPRID

00:05 Publié dans Histoire, Philosophie, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : simone weil, philosophie, politologie, sciences politiques, théorie politique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 23 septembre 2013

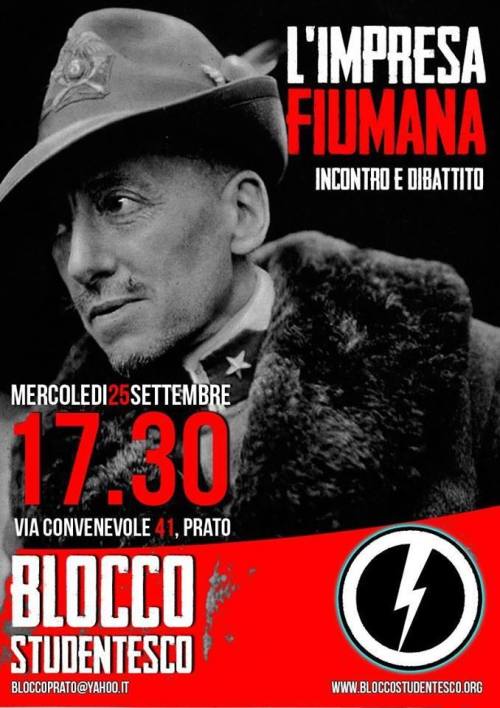

L'impresa fiumana

19:09 Publié dans Evénement, Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : italie, d'annunzio, événement, lettres, littérature, lettres italiennes, littérature italienne |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

L’etno-nazionalismo e l’ideologia völkisch

L’etno-nazionalismo e l’ideologia völkisch

Come già scritto, l’etnonazionalismo si rifà al federalismo etnico, forma modernizzata del nazionalismo etnico e dell’ideologia völkisch. Tale ideologia assegna la priorità alla tutela del Volk, inteso come comunità di Sangue e Suolo. L’etnicità costituisce per noi etnonazionalisti il criterio fondante della nazione, che prende corpo attraverso la forza del Sangue. Il singolo individuo è subordinato al volere della Volksgemeinschaft, della comunità etnica. Nella visione etnonazionalista la mappa geopolitica dell’Europa deve essere ridisegnata, attraverso la nascita di una Federazione europea etnica, costituita da Regioni-Stato, etnicamente omogenee. Ecco perché nel nostro edificio etnocentrico non vi è posto per lo Stato nazionale etnicamente eterogeneo.

Come già scritto, l’etnonazionalismo si rifà al federalismo etnico, forma modernizzata del nazionalismo etnico e dell’ideologia völkisch. Tale ideologia assegna la priorità alla tutela del Volk, inteso come comunità di Sangue e Suolo. L’etnicità costituisce per noi etnonazionalisti il criterio fondante della nazione, che prende corpo attraverso la forza del Sangue. Il singolo individuo è subordinato al volere della Volksgemeinschaft, della comunità etnica. Nella visione etnonazionalista la mappa geopolitica dell’Europa deve essere ridisegnata, attraverso la nascita di una Federazione europea etnica, costituita da Regioni-Stato, etnicamente omogenee. Ecco perché nel nostro edificio etnocentrico non vi è posto per lo Stato nazionale etnicamente eterogeneo.Il pensiero etnonazionalista si rifà ad una concezione oggettiva della nazione, che corrisponde al Volk della tradizione di Herder, Fichte e M.H. Boehm.

La forza di tale pensiero risiede proprio nella profonda carica emotiva e passionale che era (è) capace di trasmettere. Dunque la teoria völkisch, termine che in italiano si traduce in “etnonazionale”, sostiene la prevalenza di una concezione della cittadinanza che contrappone “das Volk” a “the people”, e fa sì che in Germania si sia applicato lo jus sanguinis, il diritto del Sangue: cittadino tedesco era solo chi discendeva da genitori tedeschi, parlava tedesco e propagava la cultura tedesca. Per noi etnonazionalisti lo jus sanguinis è un punto fermo, irrinunciabile.

La forza di tale pensiero risiede proprio nella profonda carica emotiva e passionale che era (è) capace di trasmettere. Dunque la teoria völkisch, termine che in italiano si traduce in “etnonazionale”, sostiene la prevalenza di una concezione della cittadinanza che contrappone “das Volk” a “the people”, e fa sì che in Germania si sia applicato lo jus sanguinis, il diritto del Sangue: cittadino tedesco era solo chi discendeva da genitori tedeschi, parlava tedesco e propagava la cultura tedesca. Per noi etnonazionalisti lo jus sanguinis è un punto fermo, irrinunciabile.Un extraeuropeo che lavora da 30 anni in una delle comunità etnonazionali che costituiscono la Padania (ad esempio il Veneto) non sarà mai un cittadino Veneto, dal momento che conserva le sue racines, la sua cultura allogena, la sua lingua. Il diritto di cittadinanza, a nostro avviso, dovrà spettare, infatti, solo a chi appartiene alla comunità etnica, cioè, ad esempio in Veneto, è cittadino chi è Veneto di sangue.

- Il federalismo basato sul criterio etnico quale elemento costitutivo di un nuovo ordine europeo (“L’Europa delle comunità etnonazionali e delle Stirpi”), in cui alla disintegrazione degli Stati nazionali etnicamente eterogenei corrisponda la nascita di una federazione di Stati regionali etnicamente omogenei; il federalismo quale forma istituzionale che consenta l’esercizio del diritto all’autodeterminazione;

- La richiesta di una nuova mappa politica dell’Europa, con la modifica degli odierni confini, da noi considerati artificiali;

- La priorità assegnata ai diritti collettivi, di gruppo, rispetto ai diritti fondamentali dell’individuo; l’avversione verso l’universalismo;

- Il rigetto della società multiculturale, considerata fonte di conflitti interetnici, la teorizzazione di forme del pensiero differenzialista;

- L’esaltazione di comunità naturali e omogenee contrapposte all’idea di nazione nata dalla rivoluzione francese;

- La relativizzazione della democrazia liberale, che necessita di correttivi etnici.

Nostro punto di riferimento culturale sono:

Nostro punto di riferimento culturale sono:-

Intereg (Internationales Institut fur Nationalitatenrecht und Regionalismus, ossia Istituto Internazionale per il diritto dei gruppi etnici e il regionalismo). Finanziato attraverso la Bayerische Landeszentrale fur Politische Bildungsarbeit (ente centrale bavarese di istruzione politica), fino alla sua scomparsa è sostenuto caldamente da Franz Joseph Strauss. Nella dichiarazione istitutiva dell’Intereg si precisa l’obbiettivo di una “relativizzazione degli stati nazionali”, al fine di conseguire “l’affermazione di un diritto dei gruppi etnici e dei princìpi dell’autodeterminazione e dell’autonoma stabilità delle regioni”.

-

BdV (Bund der Vertriebenen), è l’associazione regionale dei tedeschi espulsi dopo il 1945 dai territori orientali del Terzo Reich. BdV nasce grazie al land della Baviera e su iniziativa dei profughi dei Sudeti, la regione popolata da tedeschi grazie a cui Hitler invase la Cecoslovacchia. Il BdV non riconosce gli attuali confini della Germania.

-

SL: (Sudetendeutsche Landsmannschaft), è la lega dei profughi dei Sudeti

-

Fuev (Federalistiche Union Europaischer Volksgruppen), Unione federalista delle comunità etniche in Europa. Per gruppo etnico, secondo la Fuev, si intende una comunità che si definisce “attraverso caratteri che vuole mantenere come la propria etnia, lingua, cultura e storia”. Dopo la caduta del muro di Berlino e dell’Urss, tre milioni di cittadini di origine tedesca sono presenti negli stati post sovietici, per cui Bonn, dopo il 1989, ha iniziato a finanziare la Fuev.

-

VdA: (Verein fur das Deutschtum in Ausland), associazione per la germanicità all’estero.

-

Guy Héraud: coeditore di “Europa Etnica”, organo ufficiale della Fuev e di Intereg, figura nel comitè de patronage della “Nouvelle Ecole”, la rivista della nuova Destra francese. È il padre del federalismo etnico, la dottrina istituzionale che presenta le “Piccole Patrie”, nate dalla secessione dallo Stato nazionale multietnico, come l’estremo bastione contro la globalizzazione e l’invasione allogena. “Padre spirituale” del nazionalismo etnico è R.W. Darré e il suo testo, fondamentale per ogni etnonazionalista, è Neuadel aus Blut un Boden (Ed. italiana: Edizioni di Ar, Padova 1978): l’indissolubile binomio di “sangue e suolo” esprimeva la carica fortemente etnonazionalista e biologista del pensiero ruralistico di Darré. L’uomo, considerato innanzi tutto nella dimensione biologica di portatore e custode nel suo sangue di un prezioso patrimonio genetico, doveva realizzare la sua esistenza attraverso un’intima fusione con la terra.

Egli doveva “come la pianta mettere radici nel suolo per prendere parte alla forza primigenia, eternamente rinnovantesi della terra”. “Vogliamo far diventare di nuovo il sangue e il suolo il fondamento di una politica agraria tedesca chiamata a far risorgere il “contadinato” e con ciò superare le idee del 1789, cioè le idee del liberalismo. Perché le idee del 1789 rappresentano una Weltanschauung che nega la razza, l’adesione al contadinato invece è il nucleo centrale di una Weltanschauung che riconosce il concetto di razza. Intorno al contadinato si scindono gli spiriti del liberalismo da quelli del pensiero völkisch”. Tra i molti importanti esponenti del pensiero völkisch vi furono: Julius Langbehn (Rembrandt als Erzieher), Paul de Lagarde (Deutsche Schriften), il movimento dei Wandervoegel, W. Schwaner (Aus heiligen Schriften germanischer Völker), Hermann Ahlwardt (Der Verzweiflungskampf der arischen Völker mit dem Judentum), Artur Dinter (Die Sünde wider das Blut), H.F.K. Guenther (Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes, Rassenkunde Europas, Rassengeschichte des hellenischen und des römischen Volkes), Friederich Naumann, Alfons Stoecker e infine Georg Ritter von Schönerer.

Egli doveva “come la pianta mettere radici nel suolo per prendere parte alla forza primigenia, eternamente rinnovantesi della terra”. “Vogliamo far diventare di nuovo il sangue e il suolo il fondamento di una politica agraria tedesca chiamata a far risorgere il “contadinato” e con ciò superare le idee del 1789, cioè le idee del liberalismo. Perché le idee del 1789 rappresentano una Weltanschauung che nega la razza, l’adesione al contadinato invece è il nucleo centrale di una Weltanschauung che riconosce il concetto di razza. Intorno al contadinato si scindono gli spiriti del liberalismo da quelli del pensiero völkisch”. Tra i molti importanti esponenti del pensiero völkisch vi furono: Julius Langbehn (Rembrandt als Erzieher), Paul de Lagarde (Deutsche Schriften), il movimento dei Wandervoegel, W. Schwaner (Aus heiligen Schriften germanischer Völker), Hermann Ahlwardt (Der Verzweiflungskampf der arischen Völker mit dem Judentum), Artur Dinter (Die Sünde wider das Blut), H.F.K. Guenther (Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes, Rassenkunde Europas, Rassengeschichte des hellenischen und des römischen Volkes), Friederich Naumann, Alfons Stoecker e infine Georg Ritter von Schönerer.La battaglia è appena iniziata: siamo noi, tutti noi Popoli Padano-Alpini ed Europei che dobbiamo alzare il grido di battaglia, serrare i ranghi, e inondare le piazze di questa Terra antica dal nuovo destino. Inondarla delle nostre millenarie bandiere di libertà! E soprattutto noi etnonazionalisti dobbiamo restare uniti e legati come lo sono gli alberi di una stessa foresta, le onde di uno stesso fiume, le gocce di uno stesso sangue. Allora sarà veramente impossibile fermarci! Forza dunque: Padania, Europa in piedi!

00:08 Publié dans Révolution conservatrice, Terroirs et racines, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques, ethnisme, ethno-nationalisme, révolution conservatrice |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Réflexion sur l’État dans l’économie

Qu’est-ce que le vrai colbertisme?

Réflexion sur l’État dans l’économie

Par Guillaume Faye

Ex: http://www.gfaye.com

Par manque de formation historique et économique, on présente le « colbertisme » comme de l’interventionnisme étatique à la façon de l’État Providence ou des velléités de notre bruyant ministre du ”Redressement productif ”, M. Montebourg. Première erreur. On s’imagine aussi que le colbertisme est un dirigisme anti-libéral, le choix d’une économie bureaucratique et administrée, sous prétexte de ”volontarisme” anti-marché. Seconde erreur. Le colbertisme n’a rien à voir avec ces clichés, bien au contraire. Dans l’histoire de France récente, les véritables politiques colbertistes ont été menées par De Gaulle et Pompidou, mais certainement pas par les socialistes. Explications.

Par manque de formation historique et économique, on présente le « colbertisme » comme de l’interventionnisme étatique à la façon de l’État Providence ou des velléités de notre bruyant ministre du ”Redressement productif ”, M. Montebourg. Première erreur. On s’imagine aussi que le colbertisme est un dirigisme anti-libéral, le choix d’une économie bureaucratique et administrée, sous prétexte de ”volontarisme” anti-marché. Seconde erreur. Le colbertisme n’a rien à voir avec ces clichés, bien au contraire. Dans l’histoire de France récente, les véritables politiques colbertistes ont été menées par De Gaulle et Pompidou, mais certainement pas par les socialistes. Explications.

Colbert, homme pragmatique, principal ministre de Louis XIV, était révulsé par l’économie corporatiste, héritée de la période médiévale, avec ses corsets réglementaires, coutumiers, paralysants, fiscalistes. Un type d’économie archaïque que défendent, en fait, aujourd’hui les socialistes au pouvoir et les féodalités syndicales. Colbert était un adepte du mercantilisme anglais : il ne faut pas entraver le commerce, même avec les meilleures mais stupides intentions, mais le favoriser, afin d’augmenter la richesse et la prospérité. Mais Colbert ajouta une french touch, comme on dit : l’État ne doit pas seulement veiller à laisser en paix les acteurs économiques, à ne pas les assommer de règlements, les imposer, les contraindre, mais aussi à les aider et à leur construire un environnement favorable et à mener de grands projets d’investissement ciblés, et énormes pour l’époque : la manufacture de Saint-Gobain, celle des Gobelins, celle de Sèvres, le canal du Midi, les grandes routes royales (1), le pavage de Paris, les grands chantiers et commandes artistiques somptueuses, vitrines de la France, etc.

Colbert développa ainsi l’idée d’investissements d’État productifs : les manufactures, les infrastructures et les comptoirs coloniaux. Ces ”grands projets” constituaient à la fois un appel d’offre pour les entrepreneurs privés mais s’inscrivaient dans la doctrine mercantiliste anglo-hollandaise : créer un environnement propice à l’expansion commerciale et à l’exportation – plus d’ailleurs qu’à l’industrie. Loin de lui l’idée de faire de l’État royal un acteur interventionniste, mais plutôt un ”facilitateur”. Pour Colbert, l’État devait être économe, avec des comptes équilibrés, d’où son conflit avec le dispendieux Louvois. L’État colbertiste est libéral et initiateur à la fois. Il limite les impôts. Il favorise le commerce maritime avec les comptoirs.

Le bricolage économique et industriel des socialistes n’a donc rien à voir avec le colbertisme dont l’approximatif M. Montebourg se réclame. Le gouvernement socialiste veut au contraire (mythe marxiste de la ”nationalisation”) que l’État bureaucratique se substitue aux entreprises, les dirige avec prétention et incompétence, tout en les assommant de charges par ailleurs. D’où par exemple le prétentieux et inutile programme étatique en 34 plans techno-industriels (septembre 2013) qualifié avec cuistrerie de « troisième révolution industrielle », par lequel l’État va « faire naître les inventions de demain, les usines de demain, les produits de demain ». Les dirigeants de Google ou de X Space doivent bien rigoler. Ce projet coûtera 3,7 milliards d’euros. Ce sera un coup d’épée dans l’eau. Car les élus et les fonctionnaires sont les plus mal placés pour définir les axes de recherche-développement du secteur industriel marchand. Ce dernier sait faire son job tout seul. À ce propos, Yves de Kerdrel écrit (2) : « à quoi bon mettre l’accent sur la production de textiles intelligents lorsque dans le même temps des industriels de ce secteur se voient refuser l’autorisation d’ouvrir un site de production dans telle friche industrielle sous prétexte qu’on y aurait aperçu une espèce protégée d’escargots. » (3)

De même, la création de la récente banque publique d’investissements est une usine à gaz bureaucratique et coûteuse. L’État ferait mieux non pas de se mêler de créer des emplois, mais de faciliter leur création, non pas de subventionner ça et là des entreprises de pointe mais de cesser de pressurer de taxes, de paralyser par des règlementations l’ensemble des entreprises, d’assouplir le marché du travail, etc. L’État français socialisé est un fossoyeur qui se fait passer pour un infirmier, un destructeur d’industries qui se pose en sauveur de l’industrie. (4)

Tout autre est le véritable colbertisme, ou plutôt le néo-colbertisme de l’ère gaullo-pompidolienne. En ce temps-là (1958-1974), le budget était en équilibre. Ce qui n’empêchait l’État d’aider au financement (lui seul pouvait le faire) de grands projets structurants pour l’avenir, avec une vraie vision, pour la France et pour l’Europe. Nous sommes toujours les héritiers de ces projets, qui n’ont plus de successeurs à la hauteur.

Mentionnons pour mémoire : le programme nucléaire des 58 réacteurs (indépendance énergétique et électricité propre), le Concorde (échec commercial franco-britannique mais énormes retombées technologiques), le programme spatial (Arianespace, leader mondial), le TGV, le réseau autoroutier, Airbus, l’avionique militaire française et tant d’autres initiatives. Bien sûr il y eut des échecs cruels. (5) Le néo-colbertisme se caractérise donc par une action de l’État dans deux domaines essentiels : fournir aux entrepreneurs, forces vives d’une nation, les infrastructures nécessaires à grande échelle ; passer des commandes d’État ou proposer des partenariats dans des domaines stratégiques. Pas ”bricoler” avec des boîtes à outils socialistes, avec de la ”com” (propagande mensongère) à la rescousse.

Maintenant, pour conclure, n’oublions pas que l’État américain fédéral pratique le néo-colbertisme dans certains domaines, avec la NASA ou le pilotage du complexe militaro-industriel. L’Union européenne, elle, adepte d’un fédéralisme mou, bureaucratique, ”libéral” au mauvais sens du terme, n’a aucun projet techno-industriel de grande ampleur, et mobilisateur. Le colbertisme suppose une volonté nationale et l’Union européenne ne se pense toujours pas véritablement comme nation. Très probablement – c’est l’enseignement de l’Histoire – elle ne le fera que si l’alchimie explosive se fait entre une menace et un leader. La menace existe, et le leader européen pas encore.

Notes:

(1) Au début du XVIIe siècle, il fallait trois fois plus de temps pour aller de Paris à Marseille ou à Bordeaux que du temps de l’Empereur Trajan, à la fin du Ier siècle, lorsque les voies romaines étaient entretenues. Après les investissements routiers de Colbert, cette différence n’existe plus. Dans le Paris de Henri IV, le confort urbain était inférieur à celui de Rome ou de Pompéi : pas de rues pavées, pas d’égouts, très peu d’apports hydrauliques non phréatiques.

(2) Le Figaro, 18/09/2013, in « Colbert, reviens ! Ils sont devenus fous », p. 15, article stimulant qui m’a donné l’idée d’écrire celui-ci.

(3) Toujours le principe de précaution, frilosité écolo, que Claude Allègre a dénoncé. Voir l’interdiction, en France, même des recherches sur l’exploitation propre des gaz et huiles de schiste. Les escargots valent mieux que les emplois. Le lobby écologiste (même fanatisme que les islamistes) est dans l’utopie contre le réel. Hélas, il est écouté.

(4) La cause principale de la désindustrialisation de la France est la perte de compétitivité des entreprises industrielles, du fait du fiscalisme pseudo-social étatique, et non pas la recherche de la maximisation des profits par les ”patrons”, contrairement au discours paléo-marxiste.

(5). Par exemple, le “Plan Calcul“ gaulliste des années soixante, maladroit et trop étatiste, qui n’a pas empêché l’informatique mondiale d’être dominée par les Américains. Ou encore notre bon vieux Minitel, lui aussi trop piloté par l’État (sub regnum Mitterrandis), trop cher, balayé par l’Internet US, en dépit de ses innovations et de ses avantages.

00:05 Publié dans Economie, Nouvelle Droite, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : colbert, colbertisme, économie, politologie, théorie politique, sciences politiques, guillaume faye, nouvelle droite |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

LA CHARTE DE LA LAÏCITE

LA CHARTE DE LA LAÏCITE

De l’éducation du vulgaire ou comment on y remédie

Michel LHOMME

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Ecole/Education | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : laïcité, école, éducation, france, actualité |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

La teoria etnonazionalista

La teoria etnonazionalista

00:05 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Terroirs et racines, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : ethno-nationalisme, ethnies, livre, théorie politique, sciences politiques, politologie, ethnisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

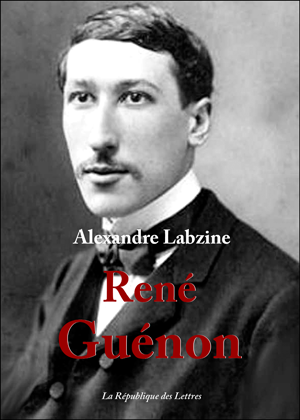

René Guénon and Eric Voegelin on the Degeneration of Right Order

René Guénon and Eric Voegelin on the Degeneration of Right Order

Ex: http://www.brusselsjournal.com

I. Introduction. No area of Western history is quite as recondite as that of the Diadochic empires, the successor-kingdoms that sprang up in the wake of Alexander the Great’s meteoric campaigns (334 – 323 BC) to subdue the world under militaristic Hellenism. One knows that the unity of Alexander’s Imperium, ever tenuous and improvisatory, broke down immediately on his death, when his “companions” fell to bellicose squabbling over bleeding chunks of the whole. Of Ptolemy’s Macedonian Egypt, one knows something – largely because the realm’s newly built Greek metropolis, Alexandria, became culturally the most important polis in the Mediterranean world, even after Octavian conquered Cleopatra and organized her Macedonian rump-state into Rome’s emergent world-federation. To transit from historical fair-certainty to historical incertitude, however, requires only that one switch focus from the Ptolemaic kingdom in the Nile Delta to the Seleucid... Indeed, to the Seleucid what? For Seleucus’ prize in the wars of the successors stretched in geographic space from Syria and Cilicia, and associated insular territories, eastward through portions of Mesopotamia and Asia Minor into the hinterlands of Parthia and Bactria. The Seleucid kingdom’s borders, as distinct from those of the more stable Ptolemaic kingdom in Egypt, remained, like the Heraclitean river, in constant flux; moreover, the Seleucid kingdom steadily withdrew in the direction of the sunrise, sacrificing its westerly regions for the defensibility of its easterly keeps, until in its last act, as the remnant Greco-Bactrian principality, it attempted to perpetuate itself against political mortality by an exodus-through-conquest from Central Asia across the Hindu Kush into Northern India.

One progresses, it seems, from obscurity to super-obscurity, as one might progress from Antioch, a polity known more or less in the annals of Western history (it served Seleucus for a capital city), to Pushkalavati, a polity all but unknown in those annals. These murky events in half-legendary places nevertheless issued in archeologically and literarily documentable consequences. When the Maurya emperor Ashoka (304 – 232 BC) converted to Buddhism around 250 BC and established it as his state religion, for example, he had to promulgate his policy in the northwest provinces of his expansive kingdom in Greek as well as in the indigenous languages. As late the First Century BC, Greek communities – if not actual poleis – still existed in what would today be Pakistan and Afghanistan, the original name of whose second largest city, Alexandria, corrupted itself over the centuries into the barbarism Kandahar. A post-Bactrian dux bellorum, Strato II, controlled a territory in the Indus Valley as late as 10 BC. Under the Seleucids and their heirs, the canons of Greek art influenced local sculpture and painting. The Bamiyan Buddhas, completed around 500 and dynamited by the Taliban in 2001, still reflected stylistic elements of Hellenistic statuary. Finally, it was through the Seleucid kingdom and its sequelae that India and the Mediterranean came into significant communication with one another so that Brahmanism and Buddhism might be known and studied by the Greek-speaking scholars of the Serapeum and something of the dialectical method might be adopted by Hindu philosophy.

This précis of Hellenistic penetration into the Near East and Central Asia in the great age of competing empires that consummated itself in the ascendancy of Rome in the West is by way of introduction to a modest comparative study of René Guénon’s Spiritual Authority & Temporal Power (1929) and Eric Voegelin’s Ecumenic Age (1974), the fourth volume of his five-volume Order and History (incipit 1956, with Israel and Revelation). The “Bactrian” chapter of the Alexandrian Drang nach Osten provides an important object of study in both books. Voegelin (1901 – 1985) could not, of course, have been known to Guénon (1886 – 1951) and it seems relatively unlikely that this particular book by Guénon would have been known to Voegelin, who, however, might have been familiar with The Crisis of the Modern Age (1927) and The Reign of Quantity & the Signs of the Times (1945); Spiritual Authority is something of a sequel to The Crisis, whose topics The Reign of Quantity revisits. Of interest is that Guénon and Voegelin, while quite different in the style of their thinking, nevertheless identify in the phenomenon of the Bactrian episode (including its Indian prequel) the same historical and spiritual significances and see in closely similar ways the relevance of that episode to an understanding of the modern phase of Western history. It goes almost without saying that for both Guénon and Voegelin, modernity is a disorderly and corrupt period in which the dominant elites have betrayed the hard-earned wisdom of philosophy and revelation and believe themselves anointed to remake a wicked world into a rational paradise liberated from superstition and bigotry, a project necessarily entailing the destruction of tradition. Modernity is “Gnostic,” in Voegelin’s term. Gnosticism designates a markedly low order of mental activity, in spiteful rebellion against the difficulties entailed by a contrasting openness to and participation in reality. Following chronology, it is natural to begin with Guénon.

II. Guénon. A student of comparative religion, Guénon took lively interest in Hinduism, Brahmanism, and Buddhism. The Hindu scriptures especially provided him with a rich symbolism, which he found that he could instructively put in parallel with, among other vocabularies, that of the Platonic lexicon. Spiritual Authority & Temporal power draws on Guénon’s knowledge of the Vedas and related documents – a propensity that can at first stymie a reader uninitiated in the specialist vocabulary. (I put myself in the category.) However, Spiritual Authority repays readerly perseverance; the references to Plato give context to the exploration of caste not as an item of sociological but rather as one of metaphysical importance. A central political-philosophical question, who should govern, as Guénon points out, is shared by Hindu religious speculation and Platonic discourse. Guénon declares the topic of his essay to be “principles that, because they stand outside of time, can be said to possess as it were a permanent actuality.” Respecting the debate about the fundamental legitimacy of temporal offices, Guénon asserts, “the most striking thing is that nobody, on either side, seems concerned to place these questions on their ground or to distinguish in a precise way between the essential and the accidental, between necessary principles and contingent circumstances.” The petulant habit of deliberately ignoring first things by itself merely provides “a fresh example [so writes Guénon] of the confusion reigning today in all domains that we consider to be eminently characteristic of the modern world for reasons already explained in our previous works.” Guénon’s phrase for the Twentieth-Century contemporaneity of his book is “the modern deviation.”

II. Guénon. A student of comparative religion, Guénon took lively interest in Hinduism, Brahmanism, and Buddhism. The Hindu scriptures especially provided him with a rich symbolism, which he found that he could instructively put in parallel with, among other vocabularies, that of the Platonic lexicon. Spiritual Authority & Temporal power draws on Guénon’s knowledge of the Vedas and related documents – a propensity that can at first stymie a reader uninitiated in the specialist vocabulary. (I put myself in the category.) However, Spiritual Authority repays readerly perseverance; the references to Plato give context to the exploration of caste not as an item of sociological but rather as one of metaphysical importance. A central political-philosophical question, who should govern, as Guénon points out, is shared by Hindu religious speculation and Platonic discourse. Guénon declares the topic of his essay to be “principles that, because they stand outside of time, can be said to possess as it were a permanent actuality.” Respecting the debate about the fundamental legitimacy of temporal offices, Guénon asserts, “the most striking thing is that nobody, on either side, seems concerned to place these questions on their ground or to distinguish in a precise way between the essential and the accidental, between necessary principles and contingent circumstances.” The petulant habit of deliberately ignoring first things by itself merely provides “a fresh example [so writes Guénon] of the confusion reigning today in all domains that we consider to be eminently characteristic of the modern world for reasons already explained in our previous works.” Guénon’s phrase for the Twentieth-Century contemporaneity of his book is “the modern deviation.”

Where Voegelin stands out as above all an exegete of symbols, Guénon strikes one as rather more a modern mythopoeic thinker who takes symbols as his main stuff of purveyance, but this is not to say that he lacks analytical ability. Rather, Guénon grasps that symbols and myths – while they might be, as Voegelin would later call them, compact – articulate reality more fully and more truly than the clichés of modern reductive thinking and that therefore one best wrests intoxicated minds from the drug of those clichés by jerking them around (rhetorically, of course) so as to get them to face and contemplate the symbols in their numinous fullness. It belongs to Guénon’s suasory strategy that the strangeness of Hindu or even European Medieval symbols can fascinate the modern subject even when, as usual, that subject diametrically misunderstands them. Get their attention, Guénon seems to say – interrupt the trance; explanations can come later. Guénon’s unblushing references to a primordial tradition, “as old as the world,” can cause him, in the case of a superficial reader, to resemble a Theosophist or a spiritualist. It is worth remembering that the hard-headed Guénon wrote studies exposing Theosophy as a “pseudo-religion” and spiritualism as mountebank hocus-pocus. But if modernity were a “deviation,” then from what would it have deviated? Although Guénon’s first chapter in Spiritual Authority bears the title “Authority and Hierarchy,” the actual topics are caste and hierarchy, two of the range of first principles that modernity has insouciantly rejected.

Caste and authority relate to one another in complex ways. Modernity bristles at one or the other of the two terms with equal righteousness, but whereas traditionalists and reactionaries acknowledge the necessity of authority, they too might nevertheless feel aversion to caste, as it has manifested itself in India since the Muslim conquest. Guénon reminds his sympathetic but possibly skeptical readers that the existing caste-system of the British Raj of his time is itself a latter-day deviation and quite as acute a one as any aspect of the Western deviation into modernity. Guénon finds the true definition of caste in the Sanskrit etymologies. Accordingly, “The principle of the institution of castes, so completely misunderstood by Westerners, is nothing else but the differing natures of human individuals; it establishes among them a hierarchy the incomprehension of which only brings disorder and confusion, and it is precisely this incomprehension that is implied in the ‘egalitarian’ theory so dear to the modern world.” Additionally, “The words used to designate caste in India signify nothing but ‘individual nature,’ implying all the characteristics attaching to the ‘specific’ human nature that [differentiates] individuals from each other.” Finally, “One could say that the distinction between castes… constitutes a veritable natural classification to which the distribution of social functions necessarily corresponds.” Guénon also asserts that caste, even in the moment when it appears, suggests a fallen condition, “a rupture of the primordial unity” by which “the spiritual power and the temporal power appear separate from one another.” The assertion will disturb no one familiar with the Platonic relation between the realm of the ideas and the realm of social action; or with the Augustinian distinction between the City of God and the City of Man.

In classical Indian society, the roles of authority on the one hand and of power on the other fell respectively to the Brahmins, or the priestly caste, and the Kshatriyas, or the warrior caste. What is at first a harmonious functional distinction becomes, however, in the course of time, “opposition and rivalry,” or so Guénon states. The functionaries of the two castes yield to their baser instincts; they commence a struggle for absolute domination in the society. The struggle finds its outcome “in total confusion, negation, and the overthrow of all hierarchy.” Long before the climax, the real functions of the two castes have lapsed in desuetude. “As for the priesthood, its essential function is the conservation and transmission of the traditional doctrine, in which every regular social organization finds its fundamental principles.” In rivalry with the warrior caste, the priesthood abandons “its proper attribute,” which is “wisdom.” As for the warrior caste, its essential function is active policing of right order within the society, including the maintenance of the priesthood, and defense of the society against external predation. In rivalry with the priesthood, the warrior caste repudiates its guidance under wisdom, whereupon its virtues (heroism, nobility, rectitude) become unintelligible. The rebellious warrior caste claims that no power exists superior to its own, a boast brutally plausible once the community has lost sight of transcendence and “where knowledge is denied any value.”

In addressing the phenomenon of “insubordination,” which as he says modernity instantiates in extremis, Guénon in fact has a particular historical episode in mind, which he treats in the chapters of Spiritual Authority called “The Revolt of the Kshatriyas” and “Usurpations of Royalty and their Consequences.” Guénon cites no dates and names no names, but the episode in question belongs to the career of the Bactrian Greeks in India. A few facts will help to vivify Guénon’s purely abstract account. I take the facts from The Greeks in Bactria and India (1951) by William Woodthorpe Tarn. The chronology runs from the late Third Century to the middle Second Century BC. The main players on the Greco-Bactrian side of the drama are Demetrius I (reigned 200 – 190 or 180 BC); two of his sons, Demetrius II (reigned 175 – 170 BC) and Apollodotus (reigned 174 – 165 BC); and a general, Menander, who soon acquired kingship (reigned 155 – 130 BC). The two sons of the first Demetrius just mentioned, and their sons and grandsons, and Menander, ruled over Indian territories exclusively, the Bactrian Kingdom itself having succumbed by degrees to nomadic invaders (the Yueh-chi) during this period, ceasing to exist after 130 BC. The main players on the Indian side of the drama are the Maurya emperors, who were Buddhists, and their usurper-successors the Sunga emperors, beginning with Pushyamitra (reigned 185 – 149), who were Brahmins. Demetrius II, Apollodotus, and Menander were likely by profession also Buddhists.

When Demetrius I with his sons and Menander as generals invaded India, he was both responding opportunistically to events in Indian politics and acting on the ambition-provoking model of concupiscential militarism, as established by Alexander and the successors. As for Pushyamitra – when he deposed the last Maurya emperor by assassination, he merely continued a long-simmering civil conflict between Brahmins and Buddhists that had been begun by Chandragupta, the first Maurya emperor, who climbed to power by promoting the Buddhist Kshatriyas against the Brahmin overlord class. Tarn notes that in this period “the Brahman was the natural enemy of the Greek,” whom the priestly class categorized under the caste system as Kshatriyas. The corollary of priestly ire against the Greeks was Buddhist (that is, Kshatriya) interest in Greek military support against the Sunga dynasts. Tarn writes, “Both Apollodotus and Menander on their coins… called themselves Soter, ‘the Saviour.’” The discussion will return to the numerous implications of these details in the section on Voegelin, to follow. At this point, we will switch focus back to Guénon and Spiritual Authority.

In the chapter on “The Revolt of the Kshatriyas,” Guénon writes, “Among almost all peoples and throughout diverse epochs – and with mounting frequency as we approach our times – the wielders of temporal power have tried… to free themselves of all superior authority, claiming to hold their power alone, and so to separate completely the spiritual from the temporal.” When the office of the purely temporal order “becomes predominant over that representing the spiritual authority,” Guénon argues, the result will be social chaos masquerading as order under blatantly “anti-metaphysical doctrines.” A doctrine qualifies as “anti-metaphysical” for Guénon when it “denies the immutable by placing… being entirely in the world of ‘becoming.’” To deny first or transcendent principles is equivalent to submitting unconditionally to what Guénon dubs “succession.” The sequence of names in the Bactro-Indian “Who’s Who” – Chandragupta, Pushyamitra, Demetrius, Apollodotus, Menander, and Eucratides – suggests the resounding vanity of mere “succession.” Guénon reminds his readers that: “Modern ‘evolutionist’ theories… are not the only examples of this error that consists in placing all reality in ‘becoming’”; rather, “theories of this kind have existed since antiquity, notably among the Greeks, and also in certain schools of Buddhism.” Let it be noted that Guénon criticizes only the political Buddhism of the Indian Time of Troubles, not the original Buddhism of the Gautama, which “never denied… the permanent and immutable principle of… being.” Guénon implicitly also criticizes the politicized Brahmanism of the same Time of Troubles, which, entangling itself in grossly temporal affairs, forfeited its legitimacy under the law of spiritual immutability.

“Immutable being” is the same as reality; it is a verbal symbol of reality taken as the inalterable nature of the totality of things. To rebel against immutable being is therefore to rebel against reality, with inevitable consequences, the same in every case. As Guénon writes, the Revolt of the Kshatriyas “overshot its mark.” The immediate victors “were not able to stop it at the precise point where they could have reaped advantage from what they had set in motion.” The denial of “Atman,” the Brahmanic First Principle, led to the denial of caste, which led to the usurpation of offices by individuals unsuited to exercise them. It fell out that the Kshatriyas, in dispossessing the Brahmins, made themselves vulnerable to rebellious dispossession by the classes formerly arranged beneath them in the social hierarchy. “The denial of caste opened the door to [one and] every usurpation, and men of the lowest caste, the Shudras, were not long in taking advantage of it.” In fact, “the denial of caste” created a power-crisis in the Indus Valley and adjacent areas that eventually drew in, first, the Persians, then Alexander himself, and then in their turn the Bactrians, who were Alexander’s epigones of the nth degree, and finally a wave of nomadic destroyer-invaders. A familiar theme in Indian politics, foreign occupation, has a history that begins long before the British Empire. Northern India had Greco-Bactrian rulers from the time of Demetrius II, Apollodotus, and Menander until the time of Julius Caesar in the West.

Guénon insists that the Revolt of the Kshatriyas with its aftermath provides only an instance of a general pattern, pedagogically useful in its starkness whose essential features appear, however, in other instances. In the chapter in Spiritual Authority on “Usurpations of Royalty and their Consequences,” Guénon writes of “an incontestable analogy… between the social organization of India and that of the Western Middle Ages,” adding that “the castes of the one and the classes of the other” reveal how “all institutions presenting a truly traditional character rest on the same natural foundations.” Similarly, the Western Middle Ages know parallel experiences to the Revolt of the Kshatriyas. “Long before the ‘humanists’ of the Renaissance, the ‘jurists’ of Philip the Fair were already the real precursors of modern secularism; and it is to this period, that is, the beginning of the Fourteenth Century, that we must in reality trace the rupture of the Western world from its own tradition.” Even before Louis IV, Philip pursued the policy of consolidating all power in France in the kingship. Guénon writes that, “Temporal ‘centralization’ is generally the sign of an opposition to spiritual authority, the influence of which governments try to neutralize in order to substitute their own.”

The analyst may follow the line from Philip in France through the Protestants in Northern Europe, with their national churches, to the secular revolutionary movements that ensue from the Jacobin usurpation of national power in France in the events of 1789 and beyond that to the political-ideological chaos of the Twentieth Century.

III. Voegelin. The fourth volume of Order and History bears the title The Ecumenic Age. The term ecumene functions centrally in Voegelin’s theory that the order of history emerges through the history of order, that is, as successive differentiations of consciousness and the concomitant increases in noetic clarity. But what is the ecumene and what is meant by The Ecumenic Age? Etymologically, the word ecumene refers to any organized district (the English word economy shares the same Greek root); by the time of the historian Polybius (200 – 118 BC), however, ecumene, which Polybius uses, had come to mean any – or rather the – geographical area over which rival empires or empire-builders might compete. Since by Polybius’ day this geographical area included everything that Alexander had conquered or tried to conquer in the East and everything that Rome had conquered in the West through the Third Punic War, the word effectively meant the known world, from Spain and Gaul to Bactria and India. In one of Voegelin’s several definitions in The Ecumenic Age, the ecumene arises when “empire as an enterprise of institutionalized power” becomes (in the phrase) “separated from the organization of a concrete society,” as happened for the first time in the case of Achamaenid expansion beyond the boundaries of the traditional Persian state in the Sixth Century BC. Persian conquests in the Greek field soon enough produced a reaction in the form of Alexander, who subdued Persia on his way to India; on Alexander’s death, as we have noted, his generals tried to wrest his conquests for themselves – the result being the Diadochic kingdoms. Voegelin writes that, “The new empires [beginning with Persia] apparently are not organized societies at all, but organizational shells that will expand indefinitely to engulf former concrete societies.” The ecumene may additionally be defined as, “the fatality of a power vacuum that attracted, and even sucked into itself, unused organizational force from outside”; and which therefore “originated in circumstances beyond control rather than in deliberate planning.”

Again in The Ecumenic Age, Voegelin writes how, in distinction to the polis, which organizes itself on the lines of a subject, the ecumene “is an object of organization rather than a subject.” This geographical-political phenomenon of the ecumene appears moreover not as “an entity given once and for all as an object for exploration,” the way the earth was given to Eratosthenes or Strabo; “it rather was something,” Voegelin writes, “that increased or diminished correlative with the expansion or contraction of imperial power” radiating from an “imperial center.” Working up to a striking phrase, “The ecumene… was not a subject of order but an object of conquest and organization; it was a graveyard of societies, including those of the conquerors, rather than a society in its own right” (emphasis added). As for the Ecumenic Age – it is the datable period, beginning with Persian expansion and ending with the disintegration of the Roman Empire in the West during which, amidst the destruction of the traditional, concrete societies, the actors of the drama forgot how to heed received wisdom while the victims of their agency had to rethink basic questions about the meaning of existence. In this way, ironically, “the Ecumenic was the age in which the great religions had their origin, and above all Christianity,” but including Buddhism, which had a Greek phase.