To listen in a player, click here [2]. To download the mp3, right-click here [2] and choose “save link as” or “save target as.” To subscribe to the CC podcast RSS feed, click here[3].

The political system of the German Republic is so fashioned as to favor long periods of stable rule under the same head of state, but even by its own standards the term of office of Angela Merkel (uninterrupted since 2005) has been very long. People had begun to experience it as a natural law, a fact of life to be endured because it could not be changed.Rivals were eased out of office or silenced, tempted away by highly remunerative posts outside politics, or overthrown by scandal.

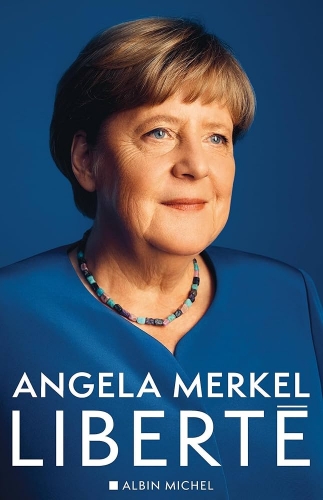

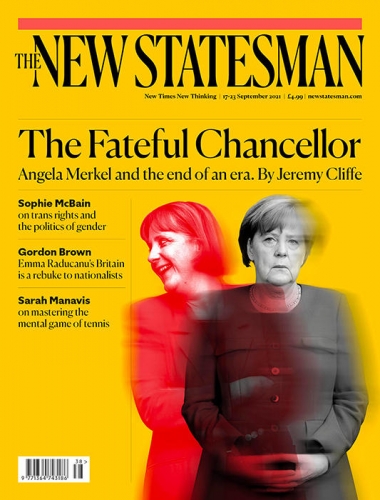

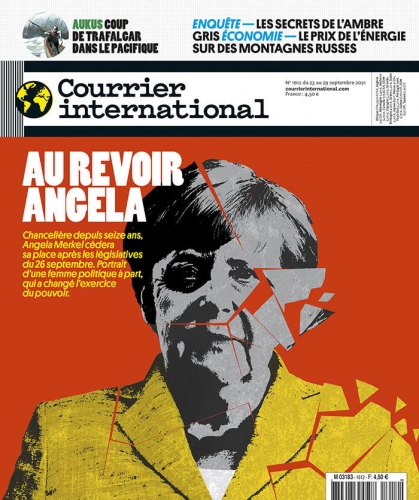

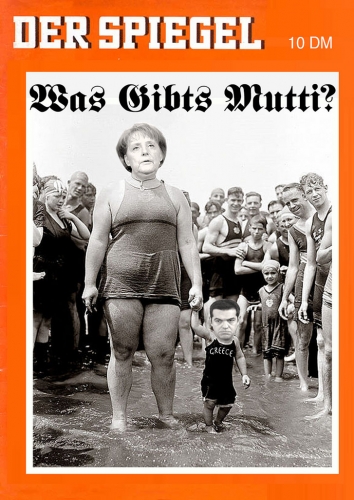

Dr. Merkel (nobody to this writer’s knowledge has investigated the possibility that her doctoral thesis was plagiarized to obtain the title in a country where such plagiarism is common) enjoys a sobriquet which suggests – in its caricaturish, specious innocence – a name lifted from the horror movie genre: Mutti, mommy. Since 2005, and still at the time of this writing, there has been an unbroken line of Merkel governments which have presided over the morphing of a nation called Germany into a location on the map of Europe which defines itself not in terms of history or race, but only in terms of economic growth. Merkel’s German Republic has become Europe’s Silicon Valley. At last, however, the end of Mutti‘s chancellorship seems imminent. She has announced that she will not stand again as party Chairman of her governing party, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), although she wishes to continue until the next general election as Chancellor. It is therefore an opportune moment to review the impact of her prolonged administration and the kind of “democracy” which enabled such a person to remain head of state for so long.

To understand politics in the Federal Republic of Germany, it is necessary to have at least a rudimentary understanding of the state’s post-war Constitution, the so-called Grundgesetz (literally “basic law”), also called the Verfassung, which was established in 1949 with the approval of the occupying forces, and which constituted the legal and ideological basis of what was at that time the West German state. From the very beginning, West Germany and West German patriotism was based not on ethnicity, but on law; a patriotism of the Constitution (Verfassungspatriotismus), for citizens of the Republic, a majority of whom were and are uneasy about expressing any loyalty to their nation, and yet happily affirm their loyalty to their Constitution. Indeed, not to pay lip service to the Grundgesetz guarantees that one will be excluded from all influential positions of office; and the livelihood of anyone – certainly anyone in a prestigious position – who openly criticizes the Constitution is in jeopardy.

The Grundgesetz aims to uphold a system of values fully integrated into the worldview of the Western powers. It does so by enshrining a constitutional system of checks and balances and a notion of equal rights, both before the law and in respect of ever-more aspects of daily life. The principle purpose of the Grundgesetz can be summarized thus: to ensure that nobody comparable to Hitler or a person of that ilk, and nothing like his party (or indeed any movement propounding an “anti-democratic” vision – or at least what is interpreted as such by the establishment) – ever holds sway in Germany again.

The Grundgesetz borrowed many features from the American Constitution. There is a President (whose role is principally symbolic); a head of state called the Chancellor (whose role roughly corresponds to a weakened version of the American presidency); two legislative houses, the Bundestag and the Bundesrat, which are comparable to the House of Representatives and the Senate; the equivalent of the Supreme Court, the Bundesverfassungsgericht; and a body called the Verfassungsschutz (Defense of the Constitution). The Bundestag is (more or less) directly elected. The regional parliament (Landrat) elects members to the Bundesrat. For decades, as in the United States and the United Kingdom, West Germany, and then reunified Germany, has had an essentially two-party system. The two principal parties have always been the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and the Christian Democratic Union-Christian Social Union (CDU-CSU), with a shadow liberal party, the Free Democratic Party (FDP) in attendance to catch protest votes. The SDP was founded in 1863 as a socialist party, and is the only political party in the German Republic to have existed before the war; the CDU-CSU (sometimes called “the Union”) claims to be Christian, social, and pro-free market; the FDP is also a strongly free market-oriented party.

As head of state, the Chancellor does not have the same powers as the American President. The Federal Court is appointed by the legislature, not the President, and enjoys retrospective powers (that is to say, it can declare laws which have already been passed as “unconstitutional,” and therefore per definition null and void). The governing committees of the major parties exercise effective control over who is selected as a parliamentary candidate on their respective party tickets. Thanks to a seniority list and a highly complex system of proportional representation combined with direct voting – a system so complicated that even educated Germans are hard-put to explain it to outsiders – a political loose cannon will not be able to make his or her way to the top of a list of candidates without falling under close establishment scrutiny. Another notable feature of this self-serving system is that the political parties are financed in large part by the taxpayer, and receive state funding in proportion to the number of votes they garner in a general election, specifically an initial eighty cents for every vote they receive. The CDU received over eleven million euros from the German taxpayer out of the 2017 general election alone. Even a small nationalist party like the National Democratic Party (NPD), which appears to boast more members of the Verfassungsschutz in its ranks than genuine nationalists, is funded in this way by the taxpayer.

Members of Parliament are payed handsomely, earning a salary of 9,541.74 euros per month. This does not include an additional expense account bonus (travelling, entertainment, etc.) of another 4,300 euros a month. As public employees, or Beamter, German parliamentarians are exempt from pension deductions from their salary. Nevertheless, they receive a substantial state pension for every year they sit in Parliament. It seems that the work of an elected representative is not so hard as to exclude the opportunity of taking up additional jobs on the side. Thus it is that all those who take part in German politics, including those who seek change, are sucked into a machinery of massive self-enrichment. I know of no state in the world where the system so effortlessly and successfully corrupts its harshest critics. Anyone who enters their local or national parliament is showered with privilege and munificence. On the other hand, there is a stick to go with the carrot: A member of any organization deemed by the state to be an enemy of the Grundgesetz is automatically disqualified from holding public office, and will find it difficult to obtain or hold any good job, or indeed any job in the public sector at all, if his status becomes public knowledge.

Article Five of the Grundgesetz enshrines the “right to free speech,” but theory and practice in this case are different beasts. Firstly, the Grundgesetz also enshrines the right to “peaceful” political protest, and, to take one example, all opposition to non-European immigration will be obstructed from day one by “peaceful” protests organized by groups which are often state-funded. Secondly, the word “peaceful” is very loosely interpreted indeed, and permits loud music to be played to disrupt events, and for demonstrators to physically obstruct conference attendees from entering a venue. Thirdly, said “peaceful” protest will be invariably accompanied by a fringe whose main form of protest will be physical intimidation, the destruction of property, and threats to any establishment which hosts any “unconstitutional,” “undemocratic,” or “fascist” group. If compelled against their will to acknowledge the existence of such non-peaceful protest at all, the “peaceful” protesters – which will include members of all the establishment political parties – will shed crocodile tears and mendaciously claim that the fringe activities in question were exceptional, but nevertheless understandable, in view of the “provocation” involved. Thus, it is the case that while free speech and free assembly are in theory guaranteed by the Constitution, in reality anyone stepping out of the narrow, and ever-narrowing, internationalist liberal and “democratic” consensus of the Republic will invite severe repercussions on their heads.

Anyone deemed to be conspiring against the Constitution is regarded ipso facto as an enemy of the state, and will be “placed under observation” by state intelligence, aka the Verfassungschutz, an organization which is directed by government appointees. The Verfassungschutz itself decides what group or movement is acting outside the limits of constitutional order. Being “placed under observation” is a political and social kiss of death. Those who receive notice that they are being “observed” by the Verfassungsschutz may attempt to “improve” their behavior, and thus be rewarded with the removal of their group from the list of those under observation – for if they do not, they run the risk of being further adjudged by the Verfassungsschutz after a period of observation to be “enemies of the Constitution” (Verfassungsfeind), after which they will be banned. The group’s being banned is not only a matter of declaring members to be outlaws, but also entails losing the right to propagate its message, and it will of course no longer benefit from state subsidies.

In recent years, this self-serving system which, since the war, has ensured that the little German state remained entirely subservient to the ideology of the West, has come under strain. The two-party system has been seriously eroded, firstly as a result of the emergence of a Green (Grünen) party in the 1980s – a party which was originally conservative, but which was soon taken over by extreme internationalists. Even though it is entirely loyal to the system, it has nevertheless disrupted the two-party balance that was an important part of the system’s stability. After the reunification of East and West in 1990, there followed other “new kids on the block”: firstly, the repackaged ex-Communist Party, which was called – with that lack of imagination for which Germans are justly famous – die Linke (“the Left”); and finally, in more recent years, a party “to the right of the CDU” called Alternative für Deutschland (Alternative for Germany, or AfD) – a name conceived as a riposte to Merkel’s famous statement that there existed “no alternative” to her policies.

The expression “to the right of the CDU” has special resonance. It is an expression which is often repeated by establishment speakers, and refers to the Republic’s red line of “democracy.” From its foundation, the German state dedicated itself to ensuring that no party would flourish which espouses views further to the political Right than the suburban “growth and security” mantras of the CDU-CSU. Not having a party of any significance “to the right of the CDU” is seen as proof of the dedication of the “new Germany” to the “values of democracy.” In this respect, all the establishment parties are in complete accord. Any group or individual daring to utter views deemed to be “to the right of the CDU” will be mocked, denounced in the press, its representatives will be hounded from public office, its organizations will be infiltrated by the Verfassungsschutz, and its activities will at every turn be intimidated by the “anti-fascist” Left with the tacit approval of the “democratic” and “peaceful” politicians of the establishment. All the time, the Sword of Damocles of “observation by the Verfassungsschutz” hangs over every movement “to the right of the CDU.”

For years, the German Republic has been at the forefront of promoting a pan-European democratic order throughout all of Europe. During the long chancellorship of Angela Merkel, who was party Chairman of the CDU as well, the aim of replacing the indigenous German population through mass immigration on such a scale as to destroy German identity forever is no longer a matter of circumspection or conspiracy, since the intention is quite open. Merkel received the Charlemagne Prize in 2008 for her services towards European unity. Significantly, the first winner of the prize was Richard von Coudenhove-Kalegri in 1950, the half-Asian writer who founded the Pan-European Union, a project for a mulatto Europe. “Germans” are, as Merkel herself defines it, “those who live in this country.” No public figure ever questioned her definition of nationhood.

Many times over the years, parties have arisen “to the right of the CDU,” but until recently the checks and hindrances briefly mentioned here have effectively thwarted every attempt by such parties to become a permanent feature of the political landscape. The two-party system was able to accommodate the Grünen, who governed in coalition with the SPD from 1998 until 2005. Since 2005, there has been a gradual decline in support for the two major parties – the so-called Volksparteien (peoples’ parties) – both in terms of votes, but also in respect of membership. With a cynicism extreme even by the low standards of the German Republic, the CDU and the SPD now govern together, while the largest opposition party, the AfD, is frozen out of all cross-party initiatives in and out of the Bundestag. So long as erosion of support is reflected in terms of abstentions, the system at least ensures that the other political parties receive the same generous funding. However, when a new party emerges and gains seats in the Bundestag, it effectively takes money away from the other parties. Since its inception in 2013, the AfD, which is now represented in every regional parliament as well as the Bundestag, is not only siphoning off votes, it is syphoning euros away from them as well, which is seen by them as an intolerable affront to what the leader of the FDP calls the “coalition of democracy.”

The system is biased to ensure that one of the two main parties remains in power even when the share of the votes for the party is low. In the 2017 election, the CDU-CSU share fell from 41.5 percent to 32.9 percent. Merkel remained in power, but it was an unwelcome warning to the “Volksparteien” that the SPD share of the vote fell as well, from 25.7 percent to 20.5 percent. Up to this time the results for the two parties have see-sawed, with results for one party rising as results for the other fell. Both parties now cling to each other in an uneasy governmental alliance.

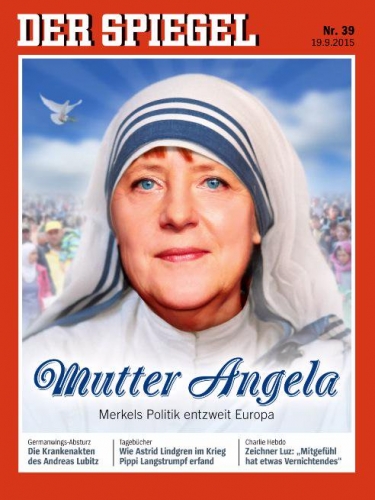

The success of the Afd is owing to two main factors: one is the courage of its members, many of whom risk intimidation, the loss of their jobs, and threats to their family just by publicly acknowledging their membership; the other is Merkel’s decision to allow a million pesudo-refugees to cross the German border in 2015. This outrageous decision was seen by many – and not only in the AfD – as an abuse of the constitutional provision which allows the acceptance of genuine refugees, as well as being a flagrant disregard of parliamentary privilege, since she took the step without consulting the Bundestag or even her own government colleagues. Some have even suggested that the decision was unconstitutional. Klaus Rüdiger Mai, writing for the ultra-internationalist Die Zeit on September 22, 2017, dismissed all such objections. It is in any case irrelevant, he opined, what the federal law or constitutional provision may stipulate, because “the European provisions override the constitutional right to asylum, which effectively has no further role to play.” Observers of the European political scene will be all too familiar with this blame-shifting game, where the national government and its supporters in the media intimate that an unpopular or legally questionable enactment or law is Brussels’ responsibility, while Brussels affirms that it is the national governments which make the decisions.

Be that as it may, the 2015 decision, which followed the bungling of the euro crisis in 2010, as well as populist sentiment growing elsewhere in Europe, has accelerated the decline of the two so-called “Volksparteien.” In spite of this, no prominent CDU member has dared challenge Mutti until this year. In an unstable world, voters in the German Republic are fearful of change, and Merkel’s non-ideological, tedious, unemotional platitudes appealed to voters feeling insecure and threatened in an age of political and environmental upheaval. So Mutti acted as a bromide. Her message, insofar as we might concede that her dreary sermons hold any substantial message at all, could be summarized as “everything is fine, we can manage, we are growing every day, there is no alternative.”

Mutti governments were especially adept at manipulating green issues to create economic growth. Every “environmentally friendly” provision, from the installation of filters in diesel cars, to the insulation of buildings with costly cladding, to new regulations for building materials and new safety provisions, all – as though by chance – have brought with them full order books in the affected branch of the economy and opened new business opportunities. The Chancellor always had an open ear for business opportunities of every kind, so long as they promote growth, boost her popularity, and pump up the GDP. The year Merkel opened the gates to a million “refugees” was the first of a series of good years for the construction industry, which had been suffering from the knock-on effect of stagnating birth rates in the form of declining demand for housing. A million “new citizens” gave the industry a shot in the arm, in addition to ongoing support in the form of complex energy-saving provisions for buildings, state-backed renewable energy investment, and costly and legally enforceable building “improvements.” It is no coincidence that costly regulations fall less heavily on the public sector than they do on the private sector. In the end, the cliché – like so many national clichés – about German obedience and awe of authority goes some way toward explaining the astonishing fear and subservience which Merkel enjoyed from the majority of citizens. CDU party conferences were not easily distinguishable from the former Communist Party conferences in East Germany, from where Merkel herself originates – and they were about as exciting.

Signs of real dissatisfaction with Mutti first made themselves felt in the CDU’s sister party, the CSU. The CSU is the equivalent of the CDU in Bavaria, to which it is confined. It has traditionally operated as the conservative wing of the CDU-CSU, and has been ruling Bavaria without interruption since the founding of the Republic. With opinion polls indicating a strong shift away from the CSU and towards the AfD in Bavaria, the President of the CSU, a trimmer named Horst Seehofer, began to take a tone more critical of “refugees,” presumably in an attempt to win back votes; it was an attempt which failed, but marked a precedent in that a member of the ruling coalition had plainly taken a line in unequivocal opposition to Mutti‘s. It was as though a sheep had barked.

The precedent was soon followed. On September 25, 2018, the CDU elected its new parliamentary Chairman, a fast-speaking, shrill stuffed shirt named Ralph Brinkhaus. This, although in itself unremarkable, thrilled mainstream journalists. It was seen as significant because Brinkhaus won in competition (practically unknown in itself) with Merkel’s favorite, Volker Kauder. It says a lot about how politics in the Republic works when one learns that Kauder, Merkel’s unquestioning and obedient servant, had been reelected at each party conference, unchallenged ever since she first became Chancellor in 2005. This little shock was followed by another, in the elections for the Bavarian regional parliament on October 14. The CDU and SPD each lost 10 percent of their vote compared to 2013, while the Grünen and AfD each gained 10 percent.

The results of the election in Hesse on October 28 were very similar, being accompanied by a sinister precedent: along with the normal ballot paper, the electors in Hesse were handed a list of fifteen questions introduced by the Grünen-CDU regional government which were described as “proposals to amend the regional constitution.” This so-called referendum, consisting of questions on a paper handed to voters at the same time as their voting slip, put forward single-sentence proposals principally aimed at linking the state constitution to the ideology of internationalism. The simplistic proposals were explained in a separate pamphlet which was not given to the voters on election day. Among other measures which were proposed not as new legislation, but as texts to be added to the state’s constitution, were the right of the state to decide on the well-being of children, the passing of laws electronically, and the existing description of Hesse as “part of the Republic of Germany” to be amended to include “and part of the EU and a united Europe.” Voters put their cross to a document of apparently harmless generalizations whose import it was not intended they should understand. All fifteen proposals for amendments to the constitution were approved with massive majorities.

In the wake of the electoral affronts to her dignity, Angela Merkel announced that she would not be standing as a candidate for Chairman of the CDU in December. Wholly in character is the non-consultative style of the woman who seems to have made this announcement without previously discussing it with her colleagues: the surprise of even her closest party comrades to the announcement seems genuine. However, her intention of resigning as party Chairman has been accompanied by her declared intention to soldier on as Chancellor. This arrogant gesture, contemptuous of both her party and the people she claims to govern, has been a bit too much even for some servants of the system to swallow. The leader of the FDP, Christian Lindner, while paying the usual obsequious tribute to Mutti, has argued that a fresh impetus is as desirable in the nation as it is in the CDU, meaning in the diplomatic language of establishment politicians that she should resign as Chancellor as well. Merkel’s curious resignation/continuation statement possibly serves two purposes: to ensure minimum disruption in her party and to the system as a whole, and to assist her preferred candidate in succeeding her. Her decision means that the Chairman of the governing party and the head of state would be two different people, something impossible in many countries, and without precedent in the Federal Republic.

A slew of candidates have rushed to apply for the job of CDU Chairman, of whom three are regarded as having a serious chance of being elected. The candidates are not chosen by party members, but rather by party delegates at the national conferences. One candidate is a woman who looks like a man, and enjoys the silly, tongue-twisting name (even for Germans) of Annegret Kamp-Karrenbauer. She/he is the Merkel favorite – if not clone – and seems to have worked for years as the Chancellor’s characterless factotum. Another candidate is the Health Minister Jens Spahn, who some consider “unsound” because he has expressed the view that an overgenerous policy regarding immigration has driven CDU voters into the arms of the AfD.

The third candidate is none other than Merkel’s personal enemy, Friedrich Merz, who happens to be a member of the exclusive Trilateral Commission, a passionate free-marketer, and a lawyer who has made himself fabulously rich advising and liaising in company takeovers and mergers after retiring from politics since Merkel beat him to the CDU chairmanship in 2005. He also sits on several supervisory boards, including BlackRock. Merz once unsuccessfully appealed to the Verfassungsgericht against a law obliging members of the Bundestag to publicly reveal what jobs they had outside of being parliamentary deputies. Unlike Merkel and his two opponents, Merz is an able and relaxed speaker. He has not been a member of the Bundestag since 2009, but no doubt the CDU could settle that small problem were he to become its Chairman. Merz also has good connections in the United States, and would undoubtedly seek to improve European-American relations, whoever happens to be the American President. There is a hint that he is not entirely unsympathetic to the Europe-as-a-superpower thesis of writers such as Jean Thiriart, a view which sees a united Europe not as a way towards a one-world state, but rather as a superpower comparable to the US or China. Sebastian Kurz in Austria also seems to be inclined to this view. But to what extent an Atlanticist like Merz would really close the borders or expel illegal “refugees” is very doubtful. The two male candidates have expressed their desire to attract dissatisfied AfD voters back into the CDU fold. From the point of view of the AfD, Merkel’s favorite should arguably be the optimal choice, since a continuation of the Chancellor’s extremist internationalism would be the best way to bolster a genuine opposition – but such a point of view is too cynical for the AfD, whose leaders have publicly declared that an AfD-CDU coalition under Merz or Spahn is conceivable, with no mention of a Kamp-Karrenbauer one.

Whatever happens in Germany in the coming months and years, the damage caused by the outgoing Chancellor is probably irreparable. The ethnic base of the German people, which was first decimated by war and then weakened by massive Turkish immigration, is unlikely to survive the final death blow of the million pseudo-refugees she welcomed in. The ethnic base is not even reproducing itself while the newcomers flourish, a development which became an established pattern during the term of a woman who, appropriately enough, is herself childless.

Churchill famously said that “our intention is to make Germany fat, but impotent.” Impotent the Germans may be, and they are also fat, literally and in terms of economic prosperity. The Federal Republic of Germany is the financial powerhouse of Europe, is profoundly sympathetic to internationalist NGOs, and endeavors to excel as the financial engine which drives the euro and the EU project as a whole. (Having been expelled from Budapest, it is no surprise to learn that George Soros’ Open Society Foundations decided to move to the more congenial political climate offered by Berlin.) Citizens of the Republic are coddled by all kinds of social insurance, rental protection, and job security. In relation to income, the prices for food, drink, and household goods are among the lowest in Europe.

If there is hope for any kind of reaction to the slow genocide of the German indigenous population, it lies, among other things, in the falling support for both wings of the dreary CDU-SPD coalition, as well as in the increasing and justified distrust of the mainstream media’s propaganda and the Republic’s “democratic” swindle, coupled with fear of and the real possibility of economic turbulence to come. Public weariness with the “same old song” of the old parties and their media friends is evident, as is widespread disquiet at Mutti‘s increasing high-handedness. Also, the AfD has achieved the feat of being the first party “right of the CDU” to be represented in all regional parliaments at the same time.

How can it be that a woman whose total personal, intellectual, physical, moral, and rhetorical mediocrity is evident at every step she takes – and from the first words she utters – has remained head of state for so long? Even more than most, German voters are drawn to authority, stability, and reassurance. Shrillness and insecurity frightens them. Merkel was very successful in presenting a picture of low-key but hugely complacent economic security and superiority, a formula which pleased millions. The German Republic, bar a few “refugee” outrages, has remained a sea of tranquility in a troubled world, and a sea of prosperity, too; both are perceived, rightly or wrongly, as Merkel achievements. She represented the benefits of a non-confrontational style of government which benignly blessed economic prosperity, especially in terms of nearly full employment, which was itself fuelled by a successful and expanding export market.

Whenever she has been confronted with strong criticism, mostly from the Linke or the AfD, she does not respond to it. She ignores it. Denounced in the Bundestag for encouraging massive income disparity by Sarah Wagenknecht, leader of Die Linken, Merkel pointedly played with her mobile phone for the duration of Wagenknecht’s speech; when attacked by the AfD’s Alice Veidel in the Bundestag, she simply rose and left the chamber.

But while Merkel made a virtue of her vacuity, German business has played another tune. Politically inept and hardly independent on the world stage, behind the scenes the German Republic has been tough in business matters, placing good sales pitches for German goods and closing many lucrative deals. A notoriously complex domestic tax system offers substantial opportunities for tax relief to companies and the self-employed, and helps to keep the wheels of the economy well-oiled. However, were for any reason those wheels to slow down or halt, such as if the export boom upon which German prosperity is wholly dependent to founder, the security-loving Germans who would be cheated of their cherished Wohlstand (prosperity) may well become less placid and complacent about the political system than they have been until now.

The democratic alliance of parties not “to the right of the CDU” will be doing all it can in the coming months to ensure that the Federal Republic remains just as Churchill wanted it to be: fat and impotent. It is not talk or logic, nor any kind of romanticism, which would lead to a collapse or rejection of the present system. A sea change can only come about if the average Hans loses the benefits and security of the post-war German consumer society – if he began, so to speak, to lose weight. A lean and hungry Germany would look very different from the docile Federal Republic that was created in 1949. It might look more like the Weimar Republic of 1929. The priority for Merkel’s successor, whoever he or she may be, will be to ensure that such a catastrophe does not befall the land of the impotent and the fat.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

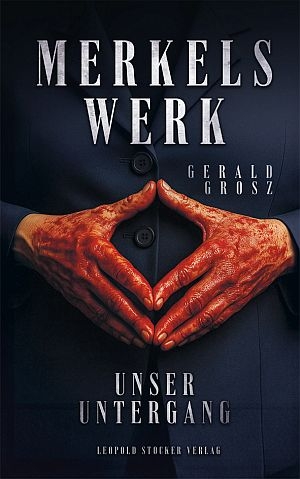

Avec son cinquième livre, « L'œuvre de Merkel – notre perte » (

Avec son cinquième livre, « L'œuvre de Merkel – notre perte » (

Der Autor der Jungen Freiheit, Hinrich Rohbohm, hat zudem für sein Buch System Merkel monatelang im Umfeld von Merkels Familie recherchiert. Demnach lehnte ihr Vater nicht nur die Wiedervereinigung, sondern auch die Gesellschaftsordnung der BRD ab. Am Abendbrottisch der Familie wurde ebenso intensiv über Politik gesprochen wie bei den regelmäßigen Treffen seines politischen »Hauskreises«, an denen auch Angela Merkel rege teilnahm. In Konflikt mit der SED-Diktatur kamen weder die Familie noch Merkel; ganz im Gegenteil, sie waren Teil der privilegierten Oberschicht und besaßen neben einem Dienstwagen auch einen Privatwagen. Ferner waren der Familie zahlreiche Russlandaufenthalte sowie Westreisen gestattet. Der SED-Staat ermöglichte Merkel zudem das Abitur und ein Physikstudium an der »roten« Karl-Marx-Universität in Leipzig, die als deutlich SED-konformer als andere Hochschulen galt. Ein Klassenkamerad Merkels erinnert sich, dass diese am Ende ihrer Schulzeit an den FDJ-Aktivitäten ihrer Abiturklasse führend mitwirkte. Auch an der Karl-Marx-Universität, wo die ideologische Indoktrination stark ausgeprägt war und es von Stasi-Mitarbeitern nur so wimmelte, übernahm sie FDJ-Funktionen. Gemäß Rohbohms Recherchen wurde Merkel von Kommilitonen als FDJ-Funktionärin bezeichnet, die Studenten »auf Linie gebracht« habe.

Der Autor der Jungen Freiheit, Hinrich Rohbohm, hat zudem für sein Buch System Merkel monatelang im Umfeld von Merkels Familie recherchiert. Demnach lehnte ihr Vater nicht nur die Wiedervereinigung, sondern auch die Gesellschaftsordnung der BRD ab. Am Abendbrottisch der Familie wurde ebenso intensiv über Politik gesprochen wie bei den regelmäßigen Treffen seines politischen »Hauskreises«, an denen auch Angela Merkel rege teilnahm. In Konflikt mit der SED-Diktatur kamen weder die Familie noch Merkel; ganz im Gegenteil, sie waren Teil der privilegierten Oberschicht und besaßen neben einem Dienstwagen auch einen Privatwagen. Ferner waren der Familie zahlreiche Russlandaufenthalte sowie Westreisen gestattet. Der SED-Staat ermöglichte Merkel zudem das Abitur und ein Physikstudium an der »roten« Karl-Marx-Universität in Leipzig, die als deutlich SED-konformer als andere Hochschulen galt. Ein Klassenkamerad Merkels erinnert sich, dass diese am Ende ihrer Schulzeit an den FDJ-Aktivitäten ihrer Abiturklasse führend mitwirkte. Auch an der Karl-Marx-Universität, wo die ideologische Indoktrination stark ausgeprägt war und es von Stasi-Mitarbeitern nur so wimmelte, übernahm sie FDJ-Funktionen. Gemäß Rohbohms Recherchen wurde Merkel von Kommilitonen als FDJ-Funktionärin bezeichnet, die Studenten »auf Linie gebracht« habe.

Politische Gewalttäter können und werden dieses Schweigen als Zustimmung und Legitimierung der Gewalt durch den Mainstream werten, solange die Brandanschläge und Gewaltexzesse im Namen der guten Sache begangen werden. Die ständige Drohkulisse durch Nazi-Vergleiche und einer linksextremen, geduldeten Gewalt auf der Straße, wird augenscheinlich ganz offen als Herrschaftsform durch das Merkel-Regime eingesetzt. Die Einheitsparteien der Grenzöffnungen ersticken so den breiten Unmut in der bürgerlichen Mitte und tabuisieren jegliche Kritik und Debatte an den epochalen Fehlentwicklungen im Land.

Politische Gewalttäter können und werden dieses Schweigen als Zustimmung und Legitimierung der Gewalt durch den Mainstream werten, solange die Brandanschläge und Gewaltexzesse im Namen der guten Sache begangen werden. Die ständige Drohkulisse durch Nazi-Vergleiche und einer linksextremen, geduldeten Gewalt auf der Straße, wird augenscheinlich ganz offen als Herrschaftsform durch das Merkel-Regime eingesetzt. Die Einheitsparteien der Grenzöffnungen ersticken so den breiten Unmut in der bürgerlichen Mitte und tabuisieren jegliche Kritik und Debatte an den epochalen Fehlentwicklungen im Land.

Un autre grand format du parti de Merkel a pris la parole: Volker Rühe. Répondant aux questions du magazine Stern, cet ancien secrétaire général de la CDU et ancien ministre de la défense ne ménage pas ses critiques à l’endroit des talents de négociatrice de la Chancelière ; sans mâcher ses mots, Rühe déclare : « Pour l’avenir de la CDU, la manière dont Merkel a négocié est un vrai désastre, alors que le salut du parti aurait dû davantage la préoccuper que sa propre situation présente ».

Un autre grand format du parti de Merkel a pris la parole: Volker Rühe. Répondant aux questions du magazine Stern, cet ancien secrétaire général de la CDU et ancien ministre de la défense ne ménage pas ses critiques à l’endroit des talents de négociatrice de la Chancelière ; sans mâcher ses mots, Rühe déclare : « Pour l’avenir de la CDU, la manière dont Merkel a négocié est un vrai désastre, alors que le salut du parti aurait dû davantage la préoccuper que sa propre situation présente ».

A titre liminaire, notons qu'une telle situation de blocage survenant immédiatement après une élection est bel et bien unique dans l'histoire de l'Allemagne depuis 1949. En revanche, la République fédérale a déjà connu des impasses constitutionnelles comparables et même un gouvernement minoritaire dans les années 1970, comme nous allons le voir plus bas.

A titre liminaire, notons qu'une telle situation de blocage survenant immédiatement après une élection est bel et bien unique dans l'histoire de l'Allemagne depuis 1949. En revanche, la République fédérale a déjà connu des impasses constitutionnelles comparables et même un gouvernement minoritaire dans les années 1970, comme nous allons le voir plus bas. Scénario 3 :

Scénario 3 :  Contrairement à ce que beaucoup peuvent imaginer, l'Allemagne a déjà connu une telle situation en 1972 après que plusieurs élus de la majorité SPD-FDP ont quitté leurs partis respectifs par rejet de l'Ostpolitik menée par Willy Brandt, tandis que l’opposition de droite menée par Rainer Barzel avait échoué à faire adopter à deux voix près sa motion de défiance constructive déposée dans le cadre de l'article 67 de la Loi fondamentale. Brandt continua donc à gouverner sans majorité jusqu'à un retournement de conjoncture politique qu'il exploita en engageant la responsabilité de son gouvernement par le dépôt d'une Motion de confiance (art. 68 LF) dont il savait qu'elle serait rejetée par le Bundestag... ce qui entraîna une dissolution de l'assemblée et une victoire de Brandt à l'élection qui s'ensuivit. Mais dans le cas présent, Angela Merkel a d'ores et déjà fait savoir qu'elle préférait une nouvelle élection que former un gouvernement minoritaire.

Contrairement à ce que beaucoup peuvent imaginer, l'Allemagne a déjà connu une telle situation en 1972 après que plusieurs élus de la majorité SPD-FDP ont quitté leurs partis respectifs par rejet de l'Ostpolitik menée par Willy Brandt, tandis que l’opposition de droite menée par Rainer Barzel avait échoué à faire adopter à deux voix près sa motion de défiance constructive déposée dans le cadre de l'article 67 de la Loi fondamentale. Brandt continua donc à gouverner sans majorité jusqu'à un retournement de conjoncture politique qu'il exploita en engageant la responsabilité de son gouvernement par le dépôt d'une Motion de confiance (art. 68 LF) dont il savait qu'elle serait rejetée par le Bundestag... ce qui entraîna une dissolution de l'assemblée et une victoire de Brandt à l'élection qui s'ensuivit. Mais dans le cas présent, Angela Merkel a d'ores et déjà fait savoir qu'elle préférait une nouvelle élection que former un gouvernement minoritaire.

Militariste ou pacifiste, raciste ou antiraciste, militariste orgueilleuse ou masochiste culpabilisée, atlantiste américanolâtre (l’ex RFA), ou stalinienne et néo-hitlérienne (l’ex RDA), la politique allemande a toujours été catastrophique. Mme Merkel, en ouvrant les frontières de l’Europe aux ”migrants” envahisseurs est dans la continuité de cette irresponsabilité allemande. Cette dernière n’est pas seulement nuisible à l’Europe mais aussi au peuple allemand lui–même

Militariste ou pacifiste, raciste ou antiraciste, militariste orgueilleuse ou masochiste culpabilisée, atlantiste américanolâtre (l’ex RFA), ou stalinienne et néo-hitlérienne (l’ex RDA), la politique allemande a toujours été catastrophique. Mme Merkel, en ouvrant les frontières de l’Europe aux ”migrants” envahisseurs est dans la continuité de cette irresponsabilité allemande. Cette dernière n’est pas seulement nuisible à l’Europe mais aussi au peuple allemand lui–même