lundi, 22 janvier 2018

Camp Bondsteel muss geschlossen werden!

Camp Bondsteel muss geschlossen werden!

Steigende Spannungen und Gefahrenherde alter und neuer Krisen erfordern die Einig-keit und das Bemühen aller Friedenskräfte zur Schliessung ausländischer Militärbasen, insbesondere der rund um den Globus in anderen Staaten aufgebauten US- und Nato-Basen. Die Kräfte, die sich um den Frieden bemühen, sind verpflichtet, die klare Botschaft zu verbreiten, dass die in anderen Staaten bestehenden US- und Nato-Militärbasen Werkzeuge des Hegemonismus, der Aggression und der Besetzung darstellen und als solche geschlossen werden müssen.

Frieden und eine alle mit einschliessende Entwicklung, die Eliminierung von Hunger und Armut bedingen eine Umverteilung der Ausgaben für die Aufrechterhaltung solcher Militärbasen zugunsten von Entwicklungsbedürfnissen, Bildung und Gesundheitsversorgung. Nach dem Ende des Kalten Krieges erwartete die ganze Menschheit Stabilität, Frieden und Gerechtigkeit in einer Welt gleichberechtigter Staaten und Völker. Diese Erwartungen erwiesen sich als vergebliche Hoffnungen.

Anstatt die US- und Nato-Basen in Europa zu schliessen, wurde der Kontinent im Laufe der zwei letzten Jahrzehnte durch eine ganze Reihe neuer US-Militärbasen in Bulgarien, Rumänien, Polen und den baltischen Staaten vernetzt. Infolgedessen gibt es heute mehr US-Militärbasen in Europa als auf dem Höhepunkt des Kalten Krieges. Frieden und Sicherheit sind brüchiger, und die Lebensqualität wird aufs Spiel gesetzt.

Diese gefährliche Entwicklung wurde 1999 eingeleitet durch die Nato-US-geführte Aggression gegen Serbien (die Bundesrepublik Jugoslawien). Am Ende der Aggression errichteten die USA in Kosovo und Metochien, dem besetzten Teil des serbischen Territoriums, eine militärische Basis, Camp Bondsteel genannt, die eine der teuersten und die grösste US-Militärbasis ist, die nach dem Vietnam-Krieg aufgebaut worden ist. Das war nicht nur illegal, sondern ein brutaler Akt der Missachtung der Souveränität und territorialen Integrität Serbiens sowie anderer Grundprinzipien des Völkerrechts. Heute gibt es gar den Plan, Camp Bondsteel zu erweitern und es – mit Blick auf geopolitische Absichten und Konfrontationen – zu einem permanenten Standort amerikanischer Truppen und zu einem Dreh- und Angelpunkt der US-Militärpräsenz in Südosteuropa zu machen.

Wir verlangen, dass der Militärstützpunkt Camp Bondsteel geschlossen wird, und genauso alle anderen US-Militärbasen in Europa und der Welt. Vorbereitungen für das Vorantreiben von Konfrontation und neuen Kriegen sind eine sinnlose Verschwendung von Geld, Energie und Entwicklungsmöglichkeiten.

Das Belgrad-Forum als integraler Teil der Friedensbewegung der Welt steht entschieden zur Initiative, alle Militärbasen in der Welt zu schliessen und die Ressourcen statt dessen den wachsenden Entwicklungsbedürfnissen und der Sehnsucht der Menschen nach einem besseren Leben zukommen zu lassen.

The Belgrade Forum for a World of Equals. Belgrad, 12. Januar 2018

(Übersetzung Zeit-Fragen)

01:00 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : états-unis, armée américaine, occupation américaine, camp bondsteel, kosovo, balkans, europe, affaires européennes, politique internationale, géopolitique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 14 janvier 2018

L’armée américaine prépare la guerre du futur : le Pentagone va aligner des essaims de drones, prêts à l’action

L’armée américaine prépare la guerre du futur : le Pentagone va aligner des essaims de drones, prêts à l’action

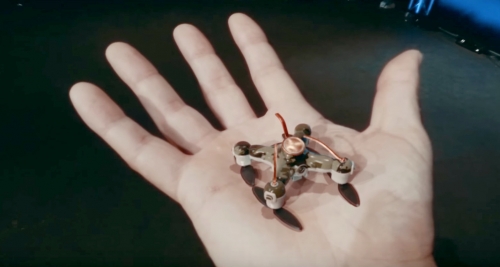

Washington. Des innovations étonnantes préparent la guerre du futur : le gouvernement américain a inauguré un projet d’armement à plusieurs niveaux, lequel prévoit l’engagement d’essaims compacts de drones. Dans le cadre de ce projet, les autorités militaires américaines envisagent de combiner l’engagement de drones en essaims sur terre et dans les airs. Le projet est à l’étude et serait sans cesse perfectionné. Les militaires américains ont en vue d’utiliser ces dispositifs dans des « zones opérationnelles complexes » comme les espaces urbains.

Les militaires américains expérimentent depuis un temps déjà assez long l’utilisation opérationnelle d’essaims de drones. Il s’agit ainsi de mettre en œuvre de petits drones intelligents en réseau qui, tel un essaim d’insectes, iraient par exemple reconnaître le terrain, échangeraient des informations ou même aborderaient des cibles et les combattraient. Les drones autonomes constitueront surtout une arme de premier plan dans les futurs combats urbains, biotopes dangereux où il s’agira surtout d’épargner des hommes et du matériel.

Dès 2016, le ministère américain de la défense avait testé des micro-drones en essaims sur un terrain en Californie. 103 drones avaient été lancés au départ de trois avions de combat. Ces petits drones ont mené plusieurs missions de combat : vol en formation, repérage collectif d’objectifs et auto-réparation. Une vidéo montre comment l’essaim trouve sa cible, l’encercle en quelques secondes et s’en approche.

Les Etats-Unis entendent utiliser cette technologie en essaim dans les airs, sur terre et en environnement maritime. La Chine, elle aussi, met les bouchées doubles pour être, dans un futur proche, prête à aligner sur un front de combat des essaims de drones.

(Source : http://www.zuerst.de ).

04:58 Publié dans Défense, Militaria | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : drones, guerre du futur, états-unis, défense, armée américaine |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 02 janvier 2018

Comparaison entre les moyens militaires américains et russes

Comparaison entre les moyens militaires américains et russes

par Jean-Paul Baquiast

Ex: http://www.europesolidaire.eu

Il est intéressant de comparer les moyens de celles-ci à ceux de l'armée américaine. Le site Russiafeed fournit des éléments à cet égard. Nous ne pouvons évidemment pas garantir la validité des chiffres. Disons seulement qu'ils paraissent très vraisemblables. Précisons qu'ils ne concernent pas les moyens aéro-navals, notamment en nombre de porte-avions et de flottes aériennes embarquées. Sur ce point l'Amérique dispose d'une supériorité écrasante. La Russie est en train de mettre au point de nouveaux missiles capables de traverser les barrières électroniques actuelles des navires américains. Mais l'US Navy ne restera certainement pas sans réponse.

Voir http://russiafeed.com/russia-vs-us-who-has-the-stronger-m...

Nous en retiendrons les éléments suivants:

Budget militaire annuel.

Etats-Unis $594 milliards, Russie $67 milliards.

Personnels d'active.

Etats-Unis 1.492.200, Russie 845.000

Bases militaires à l'étranger

Etats-Unis 800 dans 80 pays dont 174 en Allemagne, Russie 12 dont 10 dans les anciens Etats de l'Union soviétique à sa frontière sud, 2 autres l'une en Syrie et l'autre au Viet-Nam.

Arsenal nucléaire.

Nous ne reprendrons pas ici les chiffres. Disons que chacun des deux adversaires éventuels dispose de la capacité de rayer l'opposant de la carte mais aussi d'anéantir la Terre entière. Néanmoins, récemment, Donald Trump a ordonné de moderniser et renforcer les moyens américains, tètes nucléaires et ICBM, sans doute sous la pression du complexe militaro-industriel, toujours avide de nouveaux contrats, même s'ils ne reposent sur aucun besoin.

Aptitude à la « réponse asymétrique ».

On appelle ainsi, dans le cas des grandes puissances, la disponibilité de systèmes de défense aérienne, de systèmes de détection, de systèmes de défense anti-missiles. Or sur ce point la Russie, beaucoup plus exposée que l'Amérique aux attaques provenant des bases militaires qui l'encerclent, à mis au point divers systèmes qui semblent beaucoup plus efficaces que leurs homologues américains. Elle a pu les utiliser avec succès et les améliorer encore lors de la récente campagne en Syrie.

Le représentant russe à l'Otan a prévenu en été 2016 ses homologues des capacités de réponse asymétrique russes, non seulement peu couteuses, mais hautement efficace https://www.rt.com/news/337818-russia-nato-asymmetrical-r.... Voir aussi, en langue russe https://ria.ru/syria/20161006/1478654294.html?utm_source=...

Cyber-guerres.

Sur ce point, l'Amérique possède une indéniable supériorité sur la Russie, compte tenu du nombre et de la variété de systèmes d'espionnage, y compris spatiaux, dont disposent notamment la CIA et la NSA (National Security Agency). On peut penser que rien d'important de ce qui de passe à Moscou ou plus généralement en Russie n'échappe aux « grandes oreilles américaines.

Les capacités russes ont été volontairement surévaluées par le Pentagone et le Département d'Etat à propos de l'affaire dite du Russiagate. Il avait été dit que des Hackers russes étaient intervenus dans l'élection présidentielle américaine pour gêner la candidature d'Hillary Clinton. Mais après des mois d'enquêtes approfondies, les services américains n'ont jamais pu identifier la moindre cyber-intervention. Ceci n'est pas la preuve d'une « incomparable supériorité de la Russie dans la cyber-guerre », comme prétendu par le gouvernement américain, mais de l'absence de toute intervention russe d'ampleur, faute de moyens adéquats.

Dans son récent discours au Club de Valdaï, Vladimir Poutine avait ironisé sur la capacité de son pays d'intervenir dans la vie politique américaine avec des moyens électroniques. « L'Amérique est un grand Etat et non une république bananière. Dites moi si je me trompe »

11:49 Publié dans Actualité, Géopolitique, Militaria | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : états-unis, russie, politique internationale, armées, armée russe, armée américaine |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 19 septembre 2017

Les Etats-Unis risquent bientôt de ne plus pouvoir assumer les coûts des guerres

Les Etats-Unis risquent bientôt de ne plus pouvoir assumer les coûts des guerres

par Beat Kappeler, ancien syndicaliste, économiste et chroniqueur suisse

Ex: http://www.zeit-fragen.ch/fr

Tout est lié – de nouveaux soldats américains en Afghanistan, la lutte pour limiter les dettes et le déficit budgétaire ainsi que le cours du dollar et du franc suisse.

Pour garder la vue d’ensemble à plus long terme, empruntons donc une méthode de l’historien britannique Peter Heather. Dans son analyse historique «The Fall of the Roman Empire», il décrit comment – en raison de la chute des recettes étatiques et de la hausse des déficits – Rome était de moins en moins en mesure de financer ses troupes. Plus l’Empire perdit de terres et de provinces, plus l’argent se raréfia. Suite à la réduction des troupes, d’autres provinces durent être abandonnées à l’ennemi – une spirale de la mort.

Nous allons appliquer cela aux Etats-Unis, où le Congrès et le président luttent pour obtenir une limite plus élevée de l’endettement. Car les dettes sont déjà plus élevées que la production d’un an de cet immense pays. Jusqu’à présent, elles ont été financées par des crédits. Rome payait en monnaie de toujours plus mauvaise qualité. C’est là qu’intervient le levier inexorable de l’Histoire. Le déficit budgétaire est de 680 milliards de dollars. Les dépenses militaires sont au même niveau et également la croissance économique en dollars. Le calcul est donc simple – tout ce qui est produit en plus, va dans les dépenses militaires, et celles-ci sont empruntées à crédit. Ces déficits courants absorbent toute la croissance et toutes les augmentations de salaires et de prix. Suite à cela, les dettes augmentent proportionnellement plus vite que l’économie nationale, elles augmentent massivement d’année en année. Cela fait baisser les taux d’intérêt, ce qui fait augmenter le déficit.

Contrairement à la Rome antique, ces dettes militaires ont d’abord été financées avec du papier – avec des obligations émises par l’Etat. Neta Crawford du Watson Institute a évalué les dépenses pour toutes les interventions impériales dans le domaine de l’antiterrorisme en Irak, en Syrie, au Pakistan et en Afghanistan depuis 2001 à 5000 milliards de dollars. Depuis, la banque centrale a racheté 4000 milliards de dollars de dettes publiques. Des quantités correspondantes d’argent nouvellement imprimé ont alimenté la hausse boursière, les gains du secteur financier, les comptes des banques auprès de la banque centrale, mais moins l’économie nationale. Par l’acquisition des titres de créances, les intérêts de l’Etat sont tombés à 1,3% en moyenne, ou 266 milliards par an. Maintenant la banque d’émission ne veut plus acheter d’obligations d’emprunts et désire normaliser les taux d’intérêts ce qui pourrait hisser le service des intérêts des années à venir à 600 milliards et plus. C’est-à-dire que les dépenses militaires du passé vont massivement faire augmenter les déficits futurs, et l’heure de la vérité approche: ce sera pour les Etats-Unis le moment de faire des économies. Comme dans la Rome antique, il manquera chaque année davantage d’argent pour des légions entières. Comme les dépenses destinées aux redistributions à l’intérieur du pays sont largement liées et politiquement inattaquables, on ne pourra faire des économies que dans le domaine militaire, et cela massivement. La seule issue serait la Banque d’émission qui devrait retourner à la création massive d’argent. Mais cela ferait plonger le dollar, ce qui ferait encore davantage baisser la réputation des Etats-Unis. Les agences de notation menacent déjà de dégrader à nouveau la solvabilité de l’empire. Malheureusement, le franc suisse serait réévalué.

Les guerres ont aussi des conséquences humaines dramatiques, celles-ci ont également des répercussions économiques aux Etats-Unis. Pour un soldat actif en mission, il y a déjà 16 vétérans au pays. Ce sont 21 millions de personnes, pratiquement le double du nombre de travailleurs dans l’industrie américaine. Cela, il faut le payer deux fois, car il manque le rendement économique de millions de jeunes hommes et les retraites, les maladies des vétérans coûtent cher. Cela augmente également le déficit du commerce extérieur qui est déjà très élevé. La qualité de vie des Américains diminue, car il manque de l’argent à l’intérieur du pays. L’intervention massive en Afghanistan sous le président Obama – le modèle pour l’intervention actuelle – a coûté 100 milliards par an, pendant plusieurs années. C’est la même somme que le président Trump voulait dépenser pour les infrastructures bancales. Cela a aussi disparu.

Y a-t-il des alternatives? Car l’Irak, la Syrie, le Pakistan et l’Afghanistan ne se sont pas tous transformés en «a better place», comme les Américains aiment à dire.

Nombreux sont ceux qui pensent qu’avec leur extension mondiale les Etats-Unis convoitent les matières premières. Le ministre des mines de l’Afghanistan les a proposées pour 3000 milliards cette semaine. Mais on peut aussi se procurer ces mines et le pétrole du Moyen-Orient en déposant quelque chose dans les mains tendues des tribus et des dirigeants de la région. Cela coûte beaucoup moins, et l’on peut obtenir le bon comportement aussi en menaçant de bloquer tout paiement. L’Empire romain et les Habsbourgeois se sont les deux procurés deux siècles de paix en payant leur tribut aux Barbares et aux Ottomans. Cependant, si les firmes occidentales payaient, elles s’effondreraient sous la tempête d’indignation des défenseurs de l’éthique et de la gouvernance. On y ajouterait des plaintes, des décisions judiciaires et des amendes à hauteur de milliards. Mais entend-on hurler ces défenseurs de l’éthique et de la gouvernance quand il s’agit de mener de nouvelles guerres? Non, le droit des sociétés anonymes, une comptabilité péniblement propre, et une gouvernance politique entêtée sont plus importants qu’une paix facilement suspecte. On préfère la guerre aux pots-de-vin. Trump n’est pas le seul qui manque de morale, l’Occident n’en a pas non plus. •

(Traduction Horizons et débats)

18:38 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : armée américaine, us army, états-unis, politique internationale, budgets militaires |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 24 novembre 2014

A Permanent Infrastructure for Permanent War

In a September address to the United Nations General Assembly, President Barack Obama spoke forcefully about the “cycle of conflict” in the Middle East, about “violence within Muslim communities that has become the source of so much human misery.” The president was adamant: “It is time to acknowledge the destruction wrought by proxy wars and terror campaigns between Sunni and Shia across the Middle East.” Then with hardly a pause, he went on to promote his own proxy wars (including the backing of Syrian rebels and Iraqi forces against the Islamic State), as though Washington’s military escapades in the region hadn’t stoked sectarian tensions and been high-performance engines for “human misery.”

Not surprisingly, the president left a lot out of his regional wrap-up. On the subject of proxies, Iraqi troops and small numbers of Syrian rebels have hardly been alone in receiving American military support. Yet few in our world have paid much attention to everything Washington has done to keep the region awash in weaponry.

Since mid-year, for example, the State Department and the Pentagon have helped pave the way for the United Arab Emirates (UAE) to buy hundreds of millions of dollars worth of High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS) launchers and associated equipment and to spend billions more on Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) vehicles; for Lebanon to purchase nearly $200 million in Huey helicopters and supporting gear; for Turkey to buy hundreds of millions of dollars of AIM-120C-7 AMRAAM (Air-to-Air) missiles; and for Israel to stock up on half a billion dollars worth of AIM-9X Sidewinder (air-to-air) missiles; not to mention other deals to aid the militaries of Egypt, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia.

For all the news coverage of the Middle East, you rarely see significant journalistic attention given to any of this or to agreements like the almost $70 million contract, signed in September, that will send Hellfire missiles to Iraq, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar, or the $48 million Navy deal inked that same month for construction projects in Bahrain and the UAE.

The latter agreement sheds light on another shadowy, little-mentioned, but critically important subject that’s absent from Obama’s scolding speeches and just about all news coverage here: American bases. Even if you take into account the abandonment of its outposts in Iraq -- which hosted 505 U.S. bases at the height of America’s last war there -- and the marked downsizing of its presence in Afghanistan -- which once had at least 800 bases (depending on how you count them) -- the U.S. continues to garrison the Greater Middle East in a major way. As TomDispatch regular David Vine, author of the much-needed, forthcoming book Base Nation: How U.S. Military Bases Overseas Harm America and the World, points out in his latest article, the region is still dotted with U.S. bases, large and small, in a historically unprecedented way, the result of a 35-year-long strategy that has been, he writes, “one of the great disasters in the history of American foreign policy.” That’s saying a lot for a nation that’s experienced no shortage of foreign policy debacles in its history, but it’s awfully difficult to argue with all the dictators, death, and devastation that have flowed from America’s Middle Eastern machinations. Nick Turse

The Bases of War in the Middle East

From Carter to the Islamic State, 35 Years of Building Bases and Sowing DisasterBy David Vine

With the launch of a new U.S.-led war in Iraq and Syria against the Islamic State (IS), the United States has engaged in aggressive military action in at least 13 countries in the Greater Middle East since 1980. In that time, every American president has invaded, occupied, bombed, or gone to war in at least one country in the region. The total number of invasions, occupations, bombing operations, drone assassination campaigns, and cruise missile attacks easily runs into the dozens.

As in prior military operations in the Greater Middle East, U.S. forces fighting IS have been aided by access to and the use of an unprecedented collection of military bases. They occupy a region sitting atop the world’s largest concentration of oil and natural gas reserves and has long been considered the most geopolitically important place on the planet. Indeed, since 1980, the U.S. military has gradually garrisoned the Greater Middle East in a fashion only rivaled by the Cold War garrisoning of Western Europe or, in terms of concentration, by the bases built to wage past wars in Korea and Vietnam.

In the Persian Gulf alone, the U.S. has major bases in every country save Iran. There is an increasingly important, increasingly large base in Djibouti, just miles across the Red Sea from the Arabian Peninsula. There are bases in Pakistan on one end of the region and in the Balkans on the other, as well as on the strategically located Indian Ocean islands of Diego Garcia and the Seychelles. In Afghanistan and Iraq, there were once as many as 800 and 505 bases, respectively. Recently, the Obama administration inked an agreement with new Afghan President Ashraf Ghani to maintain around 10,000 troops and at least nine major bases in his country beyond the official end of combat operations later this year. U.S. forces, which never fully departed Iraq after 2011, are now returning to a growing number of bases there in ever larger numbers.

In short, there is almost no way to overemphasize how thoroughly the U.S. military now covers the region with bases and troops. This infrastructure of war has been in place for so long and is so taken for granted that Americans rarely think about it and journalists almost never report on the subject. Members of Congress spend billions of dollars on base construction and maintenance every year in the region, but ask few questions about where the money is going, why there are so many bases, and what role they really serve. By one estimate, the United States has spent $10 trillion protecting Persian Gulf oil supplies over the past four decades.

Approaching its 35th anniversary, the strategy of maintaining such a structure of garrisons, troops, planes, and ships in the Middle East has been one of the great disasters in the history of American foreign policy. The rapid disappearance of debate about our newest, possibly illegal war should remind us of just how easy this huge infrastructure of bases has made it for anyone in the Oval Office to launch a war that seems guaranteed, like its predecessors, to set off new cycles of blowback and yet more war.

On their own, the existence of these bases has helped generate radicalism and anti-American sentiment. As was famously the case with Osama bin Laden and U.S. troops in Saudi Arabia, bases have fueled militancy, as well as attacks on the United States and its citizens. They have cost taxpayers billions of dollars, even though they are not, in fact, necessary to ensure the free flow of oil globally. They have diverted tax dollars from the possible development of alternative energy sources and meeting other critical domestic needs. And they have supported dictators and repressive, undemocratic regimes, helping to block the spread of democracy in a region long controlled by colonial rulers and autocrats.

After 35 years of base-building in the region, it’s long past time to look carefully at the effects Washington’s garrisoning of the Greater Middle East has had on the region, the U.S., and the world.

“Vast Oil Reserves”

While the Middle Eastern base buildup began in earnest in 1980, Washington had long attempted to use military force to control this swath of resource-rich Eurasia and, with it, the global economy. Since World War II, as the late Chalmers Johnson, an expert on U.S. basing strategy, explained back in 2004, “the United States has been inexorably acquiring permanent military enclaves whose sole purpose appears to be the domination of one of the most strategically important areas of the world.”

In 1945, after Germany’s defeat, the secretaries of War, State, and the Navy tellingly pushed for the completion of a partially built base in Dharan, Saudi Arabia, despite the military’s determination that it was unnecessary for the war against Japan. “Immediate construction of this [air] field,” they argued, “would be a strong showing of American interest in Saudi Arabia and thus tend to strengthen the political integrity of that country where vast oil reserves now are in American hands.”

By 1949, the Pentagon had established a small, permanent Middle East naval force (MIDEASTFOR) in Bahrain. In the early 1960s, President John F. Kennedy’s administration began the first buildup of naval forces in the Indian Ocean just off the Persian Gulf. Within a decade, the Navy had created the foundations for what would become the first major U.S. base in the region -- on the British-controlled island of Diego Garcia.

In these early Cold War years, though, Washington generally sought to increase its influence in the Middle East by backing and arming regional powers like the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Iran under the Shah, and Israel. However, within months of the Soviet Union’s 1979 invasion of Afghanistan and Iran’s 1979 revolution overthrowing the Shah, this relatively hands-off approach was no more.

Base Buildup

In January 1980, President Jimmy Carter announced a fateful transformation of U.S. policy. It would become known as the Carter Doctrine. In his State of the Union address, he warned of the potential loss of a region “containing more than two-thirds of the world’s exportable oil” and “now threatened by Soviet troops” in Afghanistan who posed “a grave threat to the free movement of Middle East oil.”

Carter warned that “an attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America.” And he added pointedly, “Such an assault will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force.”

With these words, Carter launched one of the greatest base construction efforts in history. He and his successor Ronald Reagan presided over the expansion of bases in Egypt, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and other countries in the region to host a “Rapid Deployment Force,” which was to stand permanent guard over Middle Eastern petroleum supplies. The air and naval base on Diego Garcia, in particular, was expanded at a quicker rate than any base since the war in Vietnam. By 1986, more than $500 million had been invested. Before long, the total ran into the billions.

Soon enough, that Rapid Deployment Force grew into the U.S. Central Command, which has now overseen three wars in Iraq (1991-2003, 2003-2011, 2014-); the war in Afghanistan and Pakistan (2001-); intervention in Lebanon (1982-1984); a series of smaller-scale attacks on Libya (1981, 1986, 1989, 2011); Afghanistan (1998) and Sudan (1998); and the "tanker war" with Iran (1987-1988), which led to the accidental downing of an Iranian civilian airliner, killing 290 passengers. Meanwhile, in Afghanistan during the 1980s, the CIA helped fund and orchestrate a major covert war against the Soviet Union by backing Osama Bin Laden and other extremist mujahidin. The command has also played a role in the drone war in Yemen (2002-) and both overt and covert warfare in Somalia (1992-1994, 2001-).

During and after the first Gulf War of 1991, the Pentagon dramatically expanded its presence in the region. Hundreds of thousands of troops were deployed to Saudi Arabia in preparation for the war against Iraqi autocrat and former ally Saddam Hussein. In that war’s aftermath, thousands of troops and a significantly expanded base infrastructure were left in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. Elsewhere in the Gulf, the military expanded its naval presence at a former British base in Bahrain, housing its Fifth Fleet there. Major air power installations were built in Qatar, and U.S. operations were expanded in Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, and Oman.

The invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 and of Iraq in 2003, and the subsequent occupations of both countries, led to a more dramatic expansion of bases in the region. By the height of the wars, there were well over 1,000 U.S. checkpoints, outposts, and major bases in the two countries alone. The military also built new bases in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan (since closed), explored the possibility of doing so in Tajikistan and Kazakhstan, and, at the very least, continues to use several Central Asian countries as logistical pipelines to supply troops in Afghanistan and orchestrate the current partial withdrawal.

While the Obama administration failed to keep 58 “enduring” bases in Iraq after the 2011 U.S. withdrawal, it has signed an agreement with Afghanistan permitting U.S. troops to stay in the country until 2024 and maintain access to Bagram Air Base and at least eight more major installations.

An Infrastructure for War

Even without a large permanent infrastructure of bases in Iraq, the U.S. military has had plenty of options when it comes to waging its new war against IS. In that country alone, a significant U.S. presence remained after the 2011 withdrawal in the form of base-like State Department installations, as well as the largest embassy on the planet in Baghdad, and a large contingent of private military contractors. Since the start of the new war, at least 1,600 troops have returned and are operating from a Joint Operations Center in Baghdad and a base in Iraqi Kurdistan’s capital, Erbil. Last week, the White House announced that it would request $5.6 billion from Congress to send an additional 1,500 advisers and other personnel to at least two new bases in Baghdad and Anbar Province. Special operations and other forces are almost certainly operating from yet more undisclosed locations.

At least as important are major installations like the Combined Air Operations Center at Qatar’s al-Udeid Air Base. Before 2003, the Central Command’s air operations center for the entire Middle East was in Saudi Arabia. That year, the Pentagon moved the center to Qatar and officially withdrew combat forces from Saudi Arabia. That was in response to the 1996 bombing of the military’s Khobar Towers complex in the kingdom, other al-Qaeda attacks in the region, and mounting anger exploited by al-Qaeda over the presence of non-Muslim troops in the Muslim holy land. Al-Udeid now hosts a 15,000-foot runway, large munitions stocks, and around 9,000 troops and contractors who are coordinating much of the new war in Iraq and Syria.

Kuwait has been an equally important hub for Washington’s operations since U.S. troops occupied the country during the first Gulf War. Kuwait served as the main staging area and logistical center for ground troops in the 2003 invasion and occupation of Iraq. There are still an estimated 15,000 troops in Kuwait, and the U.S. military is reportedly bombing Islamic State positions using aircraft from Kuwait’s Ali al-Salem Air Base.

As a transparently promotional article in the Washington Post confirmed this week, al-Dhafra Air Base in the United Arab Emirates has launched more attack aircraft in the present bombing campaign than any other base in the region. That country hosts about 3,500 troops at al-Dhafra alone, as well as the Navy's busiest overseas port. B-1, B-2, and B-52 long-range bombers stationed on Diego Garcia helped launch both Gulf Wars and the war in Afghanistan. That island base is likely playing a role in the new war as well. Near the Iraqi border, around 1,000 U.S. troops and F-16 fighter jets are operating from at least one Jordanian base. According to the Pentagon’s latest count, the U.S. military has 17 bases in Turkey. While the Turkish government has placed restrictions on their use, at the very least some are being used to launch surveillance drones over Syria and Iraq. Up to seven bases in Oman may also be in use.

Bahrain is now the headquarters for the Navy’s entire Middle Eastern operations, including the Fifth Fleet, generally assigned to ensure the free flow of oil and other resources though the Persian Gulf and surrounding waterways. There is always at least one aircraft carrier strike group -- effectively, a massive floating base -- in the Persian Gulf. At the moment, the U.S.S. Carl Vinson is stationed there, a critical launch pad for the air campaign against the Islamic State. Other naval vessels operating in the Gulf and the Red Sea have launched cruise missiles into Iraq and Syria. The Navy even has access to an “afloat forward-staging base” that serves as a “lilypad” base for helicopters and patrol craft in the region.

In Israel, there are as many as six secret U.S. bases that can be used to preposition weaponry and equipment for quick use anywhere in the area. There’s also a “de facto U.S. base” for the Navy’s Mediterranean fleet. And it’s suspected that there are two other secretive sites in use as well. In Egypt, U.S. troops have maintained at least two installations and occupied at least two bases on the Sinai Peninsula since 1982 as part of a Camp David Accords peacekeeping operation.

Elsewhere in the region, the military has established a collection of at least five drone bases in Pakistan; expanded a critical base in Djibouti at the strategic chokepoint between the Suez Canal and the Indian Ocean; created or gained access to bases in Ethiopia, Kenya, and the Seychelles; and set up new bases in Bulgaria and Romania to go with a Clinton administration-era base in Kosovo along the western edge of the gas-rich Black Sea.

Even in Saudi Arabia, despite the public withdrawal, a small U.S. military contingent has remained to train Saudi personnel and keep bases “warm” as potential backups for unexpected conflagrations in the region or, assumedly, in the kingdom itself. In recent years, the military has even established a secret drone base in the country, despite the blowback Washington has experienced from its previous Saudi basing ventures.

Dictators, Death, and Disaster

The ongoing U.S. presence in Saudi Arabia, however modest, should remind us of the dangers of maintaining bases in the region. The garrisoning of the Muslim holy land was a major recruiting tool for al-Qaeda and part of Osama bin Laden’s professed motivation for the 9/11 attacks. (He called the presence of U.S. troops, “the greatest of these aggressions incurred by the Muslims since the death of the prophet.”) Indeed, U.S. bases and troops in the Middle East have been a “major catalyst for anti-Americanism and radicalization” since a suicide bombing killed 241 marines in Lebanon in 1983. Other attacks have come in Saudi Arabia in 1996, Yemen in 2000 against the U.S.S. Cole, and during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Research has shown a strong correlation between a U.S. basing presence and al-Qaeda recruitment.

Part of the anti-American anger has stemmed from the support U.S. bases offer to repressive, undemocratic regimes. Few of the countries in the Greater Middle East are fully democratic, and some are among the world’s worst human rights abusers. Most notably, the U.S. government has offered only tepid criticism of the Bahraini government as it has violently cracked down on pro-democracy protestors with the help of the Saudis and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Beyond Bahrain, U.S. bases are found in a string of what the Economist Democracy Index calls “authoritarian regimes,” including Afghanistan, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Ethiopia, Jordan, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Yemen. Maintaining bases in such countries props up autocrats and other repressive governments, makes the United States complicit in their crimes, and seriously undermines efforts to spread democracy and improve the wellbeing of people around the world.

Of course, using bases to launch wars and other kinds of interventions does much the same, generating anger, antagonism, and anti-American attacks. A recent U.N. report suggests that Washington’s air campaign against the Islamic State had led foreign militants to join the movement on “an unprecedented scale.”

And so the cycle of warfare that started in 1980 is likely to continue. “Even if U.S. and allied forces succeed in routing this militant group,” retired Army colonel and political scientist Andrew Bacevich writes of the Islamic State, “there is little reason to expect” a positive outcome in the region. As Bin Laden and the Afghan mujahidin morphed into al-Qaeda and the Taliban and as former Iraqi Baathists and al-Qaeda followers in Iraq morphed into IS, “there is,” as Bacevich says, “always another Islamic State waiting in the wings.”

The Carter Doctrine’s bases and military buildup strategy and its belief that “the skillful application of U.S. military might” can secure oil supplies and solve the region’s problems was, he adds, “flawed from the outset.” Rather than providing security, the infrastructure of bases in the Greater Middle East has made it ever easier to go to war far from home. It has enabled wars of choice and an interventionist foreign policy that has resulted in repeated disasters for the region, the United States, and the world. Since 2001 alone, U.S.-led wars in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, and Yemen have minimally caused hundreds of thousands of deaths and possibly more than one million deaths in Iraq alone.

The sad irony is that any legitimate desire to maintain the free flow of regional oil to the global economy could be sustained through other far less expensive and deadly means. Maintaining scores of bases costing billions of dollars a year is unnecessary to protect oil supplies and ensure regional peace -- especially in an era in which the United States gets only around 10% of its net oil and natural gas from the region. In addition to the direct damage our military spending has caused, it has diverted money and attention from developing the kinds of alternative energy sources that could free the United States and the world from a dependence on Middle Eastern oil -- and from the cycle of war that our military bases have fed.

David Vine, a TomDispatch regular, is associate professor of anthropology at American University in Washington, D.C. He is the author of Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia. He has written for the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Guardian, and Mother Jones, among other publications. His new book, Base Nation: How U.S. Military Bases Abroad Harm America and the World, will appear in 2015 as part of the American Empire Project (Metropolitan Books). For more of his writing, visit www.davidvine.net.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Book, Rebecca Solnit's Men Explain Things to Me, and Tom Engelhardt's latest book, Shadow Government: Surveillance, Secret Wars, and a Global Security State in a Single-Superpower World.

Copyright 2014 David Vine

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : politique internationale, géopolitique, géostratégie, bellicisme, états-unis, armée américaine, us navy, bases militaires |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook