I don’t believe that it will come as a surprise to most readers that Western Civilization is obsessed with the idea of being “modern,” and has been for quite a while. Concomitant with this concept is that of “newness.” If something is new, then this is equated with it being better. Conversely, things which are old are viewed as out-of-date or even useless. This mentality has wormed its way into practically every facet of life in the West. Indeed many of our industries operate on the principle of planned obsolescence – purposefully engineering their products to be superseded buy newer models on a regular basis.

Coupled with this tendency is the one similar to it that fetishizes youth while disdaining old age. Our shallow societies equate youth with beauty, and give preference to those in our societies who have the least knowledge and wisdom. Youthful foolishness is honored over staid, grumpy old wisdom. Westerners spend billions of dollars every year on surgeries and pharmaceuticals, vainly trying to stave off the inevitable effects of both entropy and their degenerate lifestyles. Nearly the entirety of our entertainment, advertising, and related establishments are focused on catering to the young – when is the last time you saw an older person hawking the latest electronic gadget or starring in the hottest new sitcom?

In his essay “On Old Age,” Cicero lauds the blessing of the aged, giving four reasons why men fear growing old and then refuting those reasons.

First, there is the reason that old age withdraws a man from the public life. Because he is not as physically vigourous, an old man could not participate in the wars and other employments requiring bodily strength. Yet, to this Cicero rejoins that there were many, many examples of old men still active in the public life who rendered great services to the state through their passion, oratory, and wisdom. Though the sword arm may be enfeebled, the swords of the tongue and the mind need not be dulled in the least.

Second, old age saps the bodily strength of a man. Yet, as Cicero through the elder Cato argues, though this is often the case, it is not always so. Even when it is, old men bring forth other areas of strength in which they exercise power with others – dignity, influence, paternal authority, knowledge, erudition, wisdom. These allow them to act in ways even greater than those who merely depend on physical strength.

Third, there is the reason that old age deprives a man of the enjoyment of sensual pleasures. Yet, Cicero points out that the aged should be thankful for this, rather than regretting it. Sensual pleasures generally corrupt a man, being the author of innumerable evils ranging from adulteries to treason. If a man did not train himself through philosophy to eschew these pleasures anywise, then he ought to be glad that old age deprives him of them. Yet, the old man may still enjoy the pleasures of intellectual attainments, of philosophy and literature and the cultivation of his property and family. So while old age robs a man of the evil, it leaves him in possession of the capability to enjoy the good.

Fourth, old age brings one nearer to death than other men. Yet, as the author notes, death comes to us all, and none will enjoy the possession of this life for very long in the grand scheme of things. A great-souled man will not fear what he cannot escape anywise, but will instead strive to act in such a way as to bring the most good through his life at every stage of it, in the ways most appropriate to each of its seasons.

These four reasons are generally complementary, and while he examines them in detail, they may essentially be boiled down to the fact that old age allows a man full access to the wisdom of both study and experience. Leading the contemplative, examined life is indeed easiest for the hoary head. At the same time, the exercise of his wisdom – in giving counsel, in providing the sum of his wisdom through the influence of oratory, of passing on his accumulated knowledge and the perspicacity that comes with long exercise of his foresight and judgment – allows him to lead the active life even while physically weakened. In a sense, he is able to participate in both of Evola’s “two paths.”

Cicero’s observations are indeed in very good accord with what we may observe in Traditional societies. Unlike cultures ravaged by modernism, Traditional societies do not view their elders as burdens or as hindrances. Instead, the elders are the repositories of their society’s collective shared wisdom. Equally as important, they are the vehicles through which this wisdom is passed on to future generations. There are very good reasons why kings and generals were often attended by councils of elders.

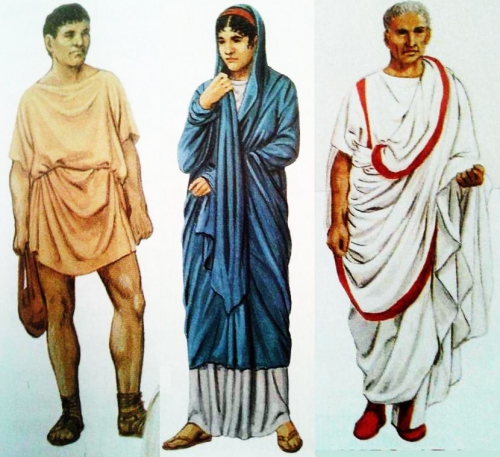

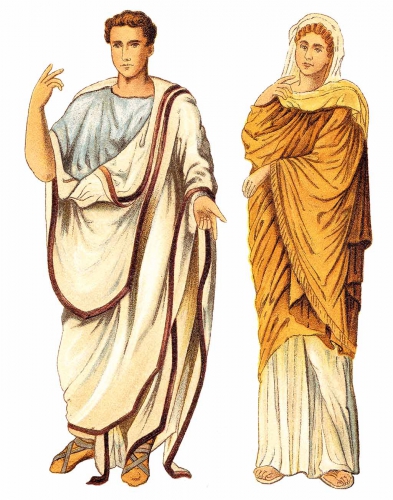

This may be seen in Cicero’s own Roman Republic. The word “senate” derives from the Latin root senex, meaning “old, aged” and by connotation describe old men who were full of wisdom. The Senate as originally constituted was intended to be a source of council for the executive, a place where the collective wisdom of aristocrats who had spent their lives in service to the state could be drawn upon by the consuls tasked with leading the nation.

In Cicero’s day – as in our own – this reverence for age and wisdom was passing away. Much of this was because Roman society was falling into the trap of idolising youth without requiring either manly vigour or sound wisdom from it. One need only look at the relative leniency with which Clodius Pulcher, of bona dea and trial for incest fame, was dealt and his ability to secure the exile of Cicero later on. Clodius was so popular with the plebs, in part, because his youthful beauty and sexual magnetism ingratiated him with an increasingly frivolous and trivially-minded populace. However, another cause for the Republic’s decadence was that her old men were acting foolishly, pursuing individual ambition at the expense of the state and nation. Much like the Baby Boomers in America, the people in Roman society who should have been passing on timeless wisdom were merely passing time pleasing themselves with flippancy.

The Scripture hints at the divide between the two types of elders when it says,

“The hoary head is a crown of glory, if it be found in the way of righteousness.” (Proverbs 16:31)

The grey hairs are the corona of golden grandeur surrounding the head of the wise and majestic elder who follows the path of wisdom and righteousness. Yet, what a cause for shame and disgrace is it for an elder to be found in frivolity, puerility, and waste!

The inordinate amount of money which Westerners spend on try to hide the effects of age and extend their youth has already been mentioned above. Unfortunately, Westerners also spend billions of dollars hiding our elders away in nursing homes and other facilities which are designed to replace traditional familial piety and enable the children to live lives just a little bit freer from their responsibilities. Nursing homes are perhaps the perfect storm of ways in which our wrongheaded society deals with our elders. In these facilities, our elders are shuffled off to die, treated like children, abused by the scum of our society – there is no pursuit of their knowledge and experience, no respect for their exalted status. That this is the case, in light of the decades-long trends in our societies, should not be surprising, for reasons which are quite manifest. Age demands things like responsibility, maturity, and faithfulness. Our youth- and pleasure-centered societies today prefer to shift their burdens onto others while living for themselves for as long as they possibly can.

Even aside from its treatment of people, the West worships newness in other ways while unmooring itself from tradition, experience, wisdom, and what is old and tried. We see this even in the very architecture of the buildings constructed in recent years. For centuries, the West built beautiful buildings, finely proportioned and richly decorated, as befitting a civilisation full of confidence in itself. This architecture built upon millennia of traditional forms and consciously sought to connect the present with the past. Now, we build angular, disjointed monstrosities which no sane or reasonable person could ever call “beautiful.”

In our literature, the West has abandoned timeless forms in poetry and prose in favour of “free verse” and “stream of consciousness” and other modernistic forms. In our music, we’ve replaced musical forms that invigourated the soul and spirit and which celebrated our history and cultural legacy with repetitive, pre-packaged garbage appealing only to the flesh. In our education system, we have replaced the traditional curricula and classical learning with useless electives on one hand, and with such narrow specialisations in technical fields on the other that the students are functionally retarded in any area outside their specialty.

All of this combined – the casting off of the anchors of our cultural traditions with their nobility and cultivation – is why very few know, and even fewer really understand, our history. “History” is the very opposite of today’s zeitgeist that worships at the altar of modernity and innovation. History, by its very nature, turns the eye back to the past, demanding that the soul learn from those who have gone on before. When the focus of your attention only goes back a few months, it’s hard to connect with music, poetry, architecture, or philosophy which is centuries old. And when your primary concern is getting the latest iPhone so that millennials will think you’re “with it,” it’s hard to be sympathetic to your elders who are there, just waiting to pass on to you our combined civilisational wisdom, if only you’d have the sense to receive it.

Restoring a reverence for the elders of our society – and doing so in a timely enough fashion that the elders remaining will be ones with any traditional wisdom left to pass on – ought to be a long-term goal for Traditionalists and neoreactionaries. The idolatry of youth must give way once again to the veneration of the elders. This is a shift in polarity which will go completely against the grain of so-called modern society. Yet, it is one which must take place – and which we must encourage at every step and in every way we can – if the good and noble elements of our civilisation are to be preserved for future generations.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg