samedi, 24 mai 2025

Orthodoxie et hérésie durant l’Antiquité tardive

Orthodoxie et hérésie durant l’Antiquité tardive

Claude Bourrinet

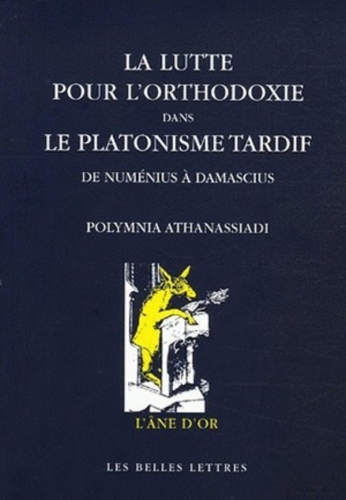

La période qui s’étend du IIIe siècle de l’ère chrétienne au 6ème, ce qu’il est convenu d’appeler, depuis les débuts de l’Âge moderne, le passage de l’Antiquité gréco-romaine au Moyen Âge (ou Âges gothiques), fait l’objet, depuis quelques années, d’un intérêt de plus en plus marqué de la part de spécialistes, mais aussi d’amateurs animés par la curiosité des choses rares, ou poussés par des besoins plus impérieux. De nombreux ouvrages ont contribué à jeter des lueurs instructives sur un moment de notre histoire qui avait été négligée, voire méprisée par les historiens. Ainsi avons-nous pu bénéficier, à la suite des travaux d’un Henri-Irénée Marrou, qui avait en son temps réhabilité cette époque prétendument « décadente », des analyses érudites et perspicaces de Pierre Hadot, de Lucien Jerphagnon, de Ramsay MacMullen, de Christopher Gérard et d’autres, tandis que les ouvrages indispensable, sur la résistance païenne, de Pierre de Labriolle et d’Alain de Benosit étaient réédités. Polymnia Athanassiadi, professeur d’histoire ancienne à l’Université d’Athènes, a publié, en 2006, aux éditions Les Belles Lettres, une recherche très instructive, La Lutte pour l’orthodoxie dans le platonisme tardif, que je vais essayer de commenter.

Avant tout, il est indispensable de s’interroger sur l’occultation, ou plutôt l’aveuglement (parce que l’acte de voiler supposerait une volonté assumée de cacher, ce qui n’est pas le cas), qu’ont manifesté les savants envers cette période qui s’étend sur plusieurs siècles. L’érudition classique, puis romantique (laquelle a accentué l’erreur de perspective) préféraient se pencher sur celle, plus valorisante, du 5ème siècle athénien, ou de l’âge d’or de l’Empire, d’Auguste aux Antonins. Pourquoi donc ce dédain, voire ce quasi déni ? On s’aperçoit alors que, bien qu’aboutissant à des présupposés laïques, la science historique a été débitrice de la vision chrétienne de l’Histoire. On a soit dénigré ce qu’on appela le « Bas Empire », en montrant qu’il annonçait l’obscurantisme, ou bien on l’a survalorisé, en dirigeant l’attention sur l’Église en train de se déployer, et sur le christianisme, censé être supérieur moralement. On a ainsi souligné dans le déclin, puis l’effondrement de la civilisation romaine, l’avènement de la barbarie, aggravée, aux yeux d’un Voltaire, par un despotisme asiatique, que Byzance incarna pour le malheur d’une civilisation figée dans de louches et imbéciles expressions de la torpeur spirituelle, dans le même temps qu’on saluait les progrès d’une vision supposée supérieure de l’homme et du monde.

Plus pernicieuse fut la réécriture d’un processus qui ne laissa guère de chances aux vaincus, lesquels faillirent bien disparaître totalement de la mémoire. À cela, il y eut plusieurs causes. D’abord, la destruction programmée, volontaire ou non, des écrits païens par les chrétiens. Certains ont pu être victimes d’une condamnation formelle, comme des ouvrages de Porphyre, de Julien l’Empereur, de Numénius, d’autres ont disparu parce qu’ils étaient rares et difficiles d’accès, comme ceux de Jamblique, ou bien n’avaient pas la chance d’appartenir au corpus technique et rhétorique utile à la propédeutique et à la méthodologie allégorique utilisées par l’exégèse chrétienne. C’est ainsi que les Ennéades de Plotin ont survécu, contrairement à d’autres monuments, considérables, comme l’œuvre d’Origène, pourtant chrétien, mais plongé dans les ténèbres de l’hérésie, qu’on ne connaît que de seconde main, dans les productions à des fins polémiques d’un Eusèbe.

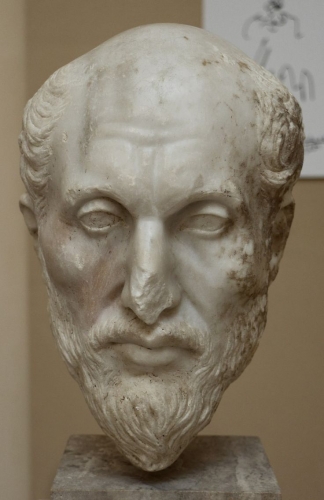

La philosophie, à partir du 2ème siècle, subit une transformation profonde, et se « platonise » en absorbant les écoles concurrentes comme l’aristotélisme et le stoïcisme, ou en les rejetant, comme l’académisme ou l’épicurisme, en s’appuyant aussi sur un corpus mystique, plus ou moins refondé, comme l’hermétisme, le pythagorisme ou les oracles chaldaïques. De Platon, on ne retient que le théologien. Le terme « néoplatonisme » est peu satisfaisant, car il est un néologisme qui ne rend pas compte de la conscience qu’avaient les penseurs d’être les maillons d’une « chaîne d’or », et qui avaient hautement conscience d’être des disciples de Platon, des platoniciens, des platonici, élite considérée comme une « race sacrée ». Ils clamaient haut et fort qu’il n’y avait rien de nouveau dans ce qu’ils avançaient. Cela n’empêchait pas des conflits violents (en gros, les partisans d’une approche « intellectualisante » du divin, de l’autre ceux qui mettent l’accent sur le rituel et le culte, bien que les deux camps ne fussent pas exclusifs l’un de l’autre). Le piège herméneutique dont fut victime l’appréhension de ces débats qui éclosent au seuil du Moyen Âge, et dont les enjeux furent considérables, tient à ce que le corpus utilisé (en un premier temps, les écrits de Platon) et les méthodes exégétiques, préparent et innervent les pratiques méthodologiques chrétiennes. Le « néoplatonisme » constituerait alors le barreau inférieur d’une échelle qui monterait jusqu’à la théologie chrétienne, sommet du parcours, et achèvement d’une démarche métaphysique dont Platon et ses exégètes seraient le balbutiement ou la substance qui n’aurait pas encore emprunté sa forme véritable.

Or, non seulement la pensée « païenne » s’inséra difficilement dans un schéma dont la cohérence n’apparaît qu’à l’aide d’un récit rétrospectif peu fidèle à la réalité, mais elle dut batailler longuement et violemment contre les gnostiques, puis contre les chrétiens, quand ces derniers devinrent aussi dangereux que les premiers, quitte à ne s’avouer vaincue que sous la menace du bras séculier.

Cette résistance, cette lutte, Polymnia Athanassiadi nous la décrit très bien, avec l’exigence d’une érudite maîtrisant avec talent la technique philologique et les finesses philosophiques d’un âge qui en avait la passion. Mais ce qui donne encore plus d’intérêt à cette recherche, c’est la situation (pour parler comme les existentialistes) adoptée pour en rendre compte. Car le point de vue platonicien est suivi des commencements à la fin, de Numénius à Damascius, ce qui bascule complètement la compréhension de cette époque, et octroie une légitimité à des penseurs qui avaient été dédaignés par la philosophie universitaire. Ce n’est d’ailleurs pas une moindre gageure que d’avoir reconsidéré l’importance de la théurgie, notamment celle qu’a conçue et réalisée Jamblique, dont on perçoit la noblesse de la tâche, lui qui a souvent fort mauvaise presse parmi les historiens de la pensée.

Pendant ces temps très troublés, où l’Empire accuse les assauts des Barbares, s’engage dans un combat sans merci avec l’ennemi héréditaire parthe, où le centre du pouvoir est maintes fois disloqué, amenant des guerres civiles permanentes, où la religiosité orientale mine l’adhésion aux dieux ancestraux, l’hellénisme (qui est la pensée de ce que Paul Veyne nomme l’Empire gréco-romain) est sur la défensive. Il lui faut trouver une formule, une clé, pour sauver l’essentiel, la terre et le ciel de toujours. Nous savons maintenant que c’était un combat vain (en apparence), en tout cas voué à l’échec, dès lors que l’État allait, par un véritable putsch religieux, imposer le culte galiléen. Durant trois ou quatre siècles, la bataille se déroulerait, et le paganisme perdrait insensiblement du terrain. Puis on se réveillerait avec un autre ciel, une autre terre. Comme le montre bien Polymnia Athanassiadi, cette « révolution » se manifeste spectaculairement dans la relation qu’on cultive avec les morts : de la souillure, on passe à l’adulation, au culte, voire à l’idolâtrie des cadavres.

À travers cette transformation des cœurs, et de la représentation des corps, c’est une nouvelle conception de la vérité qui vient au jour. Mais, comme cela advient souvent dans l’étreinte à laquelle se livrent les pires ennemis, un rapport spéculaire s’établit, où se mêlent attraction et répugnance. Récusant la notion de Zeitgeist, trop vague, Polymnia Athanassiadi préfère celui d’« osmose » pour expliquer ce phénomène universel qui poussa les philosophes à définir, dans le champ de leurs corpus, une « orthodoxie », tendance complètement inconnue de leurs prédécesseurs. Il s’agit là probablement de la marque la plus impressionnante d’un âge qui, par ailleurs, achèvera la logique de concentration extrême des pouvoirs politique et religieux qui était contenu dans le projet impérial. C’est dire l’importance d’un tel retournement des critères de jugement intellectuel et religieux pour le destin de l’Europe.

Il serait présomptueux de restituer ici toutes les composantes d’un processus historique qui a mis des siècles pour réaliser toutes ses virtualités. On s’en tiendra à quelques axes majeurs, représentatifs de la vision antique de la quête de vérité, et généralement dynamisés par des antithèses récurrentes.

L’hellénisme, qui a irrigué culturellement l’Empire romain et lui a octroyé une armature idéologique, sans perdre pour autant sa spécificité, notamment linguistique (la plupart des ouvrages philosophiques ou mystiques sont en grec) est, à partir du 2ème siècle, sur une position défensive. Il est obligé de faire face à plusieurs dangers, internes et externes. D’abord, un scepticisme dissolvant s’empare des élites, tandis que, paradoxalement, une angoisse diffuse se répand au moment même où l’Empire semble devoir prospérer dans la quiétude et la paix. D’autre part, les écoles philosophiques se sont pour ainsi dire scolarisées, et apparaissent souvent comme des recettes, plutôt que comme des solutions existentielles. Enfin, de puissants courants religieux, à forte teneur mystique, parviennent d’Orient, sémitique, mais pas seulement, et font le siège des âmes et des cœurs. Le christianisme est l’un d’eux, passablement hellénisé, mais dont le noyau est profondément judaïque.

Plusieurs innovations, matérielles et comportementales, vont se conjuguer pour soutenir l’assaut contre le vieux monde. Le remplacement du volume de papyrus par le Codex, le livre que nous connaissons, compact, maniable, d’une économie extraordinaire, outil propice à la pérégrination, à la clandestinité, sera déterminant dans l’émergence de cette autre figure insolite qu’est le missionnaire, le militant. Les païens, par conformisme traditionaliste, étaient attachés à l’antique mode de transmission de l’écriture, et l’idée de convertir autrui n’appartenait pas à la Weltanschauung gréco-romaine. Nul doute qu’on ait là l’un des facteurs les plus assurés de leur défaite finale.

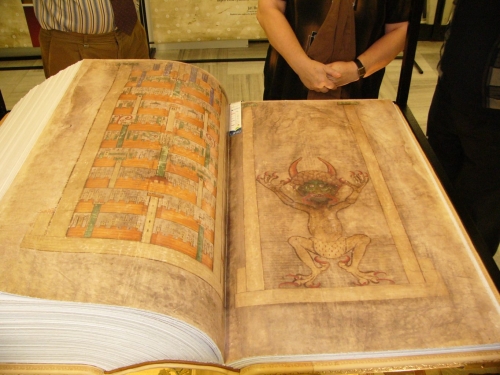

Le livre possède aussi une qualité intrinsèque, c’est que la disposition de ses pages reliées et consultables à loisir sur le recto et le verso, ainsi que la continuité de lecture que sa facture induit, le rendent apte à produire un programme didactique divisé en parties cohérentes, en une taxinomie. Il est par excellence porteur de dogme. Le canon, la règle, l’orthodoxie sont impliqués dans sa présentation ramassée d’un bloc, laissant libre cours à la condamnation de l’hérésie, terme qui, de positif qu’il était (c’était d’abord un choix de pensée et de vie) devient péjoratif, dans la mesure même où il désigne l’écart, l’exclu. Très vite, il sera l’objet précieux, qu’on parera précieusement, et qu’on vénérera. Les religions du Livre vont succéder à celles de la parole, le commentaire et l’exégèse du texte figé à la recherche libre et à l’accueil « sauvage » du divin.

Pour les Anciens, la parole, « créature ailée », selon Homère, symbolise la vie, la plasticité de la conscience, la possibilité de recevoir une pluralité de messages divins. Rien de moins étrange pour un Grec que la théophanie. Le vecteur oraculaire est au centre de la culture hellénique. C’est pourquoi les Oracles chaldaïques, création du fascinant Julien le théurge, originaire de la cité sacrée d’Apamée, seront reçus avec tant de faveur. En revanche la théophanie chrétienne est un événement unique: le Logos s’est historiquement révélé aux hommes. Cependant, sa venue s’est faite par étapes, chez les Juifs et les Grecs d’abord, puis sous le règne d’Auguste. L’incarnation du Verbe est conçue comme un progrès, et s’inscrit dans un temps linéaire. Tandis que le Logos, dans la vision païenne, intervient par intermittence. En outre, il révèle une vérité qui n’est cernée ni par le temps, ni par l’espace. La Sophia appartient à tous les peuples, d’Occident et d’Orient, et non à un « peuple élu ». C’est ainsi que l’origine de Jamblique, de Porphyre, de Damascius, de Plotin, les trois premiers Syriens, le dernier Alexandrin, n’a pas été jugé comme inconvenante. Il existait, sous l’Empire, une koïnè théologique et mystique.

Que le monothéisme sémitique ait agi sur ce recentrement du divin sur lui-même, à sa plus simple unicité, cela est plus que probable, surtout dans cette Asie qui accueillait tous les brassages de populations et de doctrines, pour les déverser dans l’Empire. Néanmoins, il est faux de prétendre que le néoplatonisme fût une variante juive du platonisme. Il est au contraire l’aboutissement suprême de l’hellénisme mystique. Comme les Indiens, que Plotin ambitionnait de rejoindre en accompagnant en 238 l’expédition malheureuse de Gordien II contre le roi perse Chahpour, l’Un peut se concilier avec la pluralité. Jamblique place les dieux tout à côté de Dieu. Plus tard, au 5ème siècle, Damascius, reprenant la théurgie de Jamblique et l’intellectualité de Plotin (3ème siècle), concevra une voie populaire, rituelle et cultuelle, nécessairement plurielle, et une voie intellective, conçue pour une élite, quêtant l’union avec l’Un. Le pèlerinage, comme sur le mode chrétien, sera aussi pratiqué par les païens, dans certaines villes « saintes », pour chercher auprès des dieux le salut.

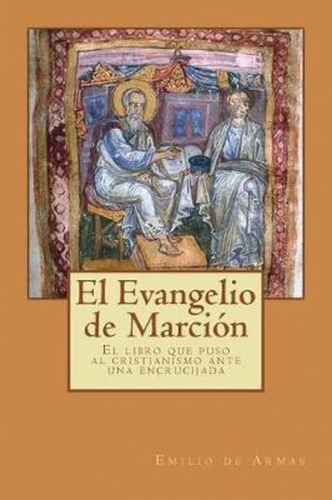

Les temps imposaient donc un changement dans la religiosité, sous peine de disparaître rapidement. Cette adaptation fut le fait de Numénius qui, en valorisant Platon le théologien, Platon le bacchant, comme dira Damascius, et en éliminant du corpus sacré les sceptiques et les épicuriens, parviendra à déterminer la première orthodoxie païenne, bien avant la chrétienne, qui fut le fruit des travaux de Marcion le gnostique, et des chrétien plus ou moins bien-pensants, Origène, Valentin, Justin martyr, d’Irénée et de Tertullien. La notion centrale de cette tâche novatrice est l’homodoxie, c’est-à-dire la cohérence verticale, dans le temps, de la doctrine, unité garantie par le mythe de la « chaîne d’or », de la transmission continue de la sagesse pérenne. Le premier maillon est la figure mythique de Pythagore, mais aussi Hermès Trismégiste et Orphée. Nous avons-là une nouvelle religiosité qui relie engagement et pensée. Jamblique sera celui qui tentera de jeter les fondations d’une Église, que Julien essaiera d’organiser à l’échelle de l’Empire, en concurrence avec l’Église chrétienne.

Quand les persécutions anti-païennes prendront vraiment consistance, aux 4ème, 5ème et 6ème siècles, de la destruction du temple de Sérapis, à Alexandrie, en 391, jusqu’à l’édit impérial de 529 qui interdit l’École platonicienne d’Athènes, le combat se fit plus âpre et austère. Sa dernière figure fut probablement la plus attachante. La vie de Damascius fut une sorte de roman philosophique. À soixante-dix ans, il décide, avec sept de ses condisciples, de fuir la persécution et de se rendre en Perse, sous le coup du mirage oriental. Là, il fut déçu, et revint dans l’Empire finir ses jours, à la suite d’un accord entre l’Empereur et le Roi des Rois.

De Damascius, il ne reste qu’une partie d’une œuvre magnifique, écrite dans un style déchiré et profondément poétique. Il a redonné des lettres de noblesse au platonisme, mais ses élans mystiques étaient contrecarrés par les apories de l’expression, déchirée comme le jeune Dionysos par les Titans, dans l’impossibilité qu’il était de dire le divin, seulement entrevu. La voie apophatique qui fut la sienne annonçait le soufisme et une lignée de mystiques postérieure, souvent en rupture avec l’Église officielle.

Nous ne faisons que tracer brièvement les grands traits d’une épopée intellectuelle que Polymnia Athanassiadi conte avec vie et talent. Il est probable que la défaite des païens provient surtout de facteurs sociaux et politiques. La puissance de leur pensée surpassait celle des chrétiens qui cherchaient en boitant une voie rationnelle à une religion qui fondamentalement la niait, folie pour les uns, sagesse pour les autres. L’État ne pouvait rester indifférent à la propagation d’une secte qui, à la longue, devait devenir une puissance redoutable. L’aristocratisme platonicien a isolé des penseurs irrémédiablement perdus dans une société du ressentiment qui se massifiait, au moins dans les cœurs et les esprits, et la tentative de susciter une hiérarchie sacrée a échoué pitoyablement lors du bref règne de Julien.

Or, maintenant que l’Église disparaît en Europe, il est grand temps de redécouvrir un pan de notre histoire, un fragment de nos racines susceptible de nous faire recouvrer une part de notre identité. Car ce qui frappe dans l’ouvrage de Polymnia Athanassiadi, c’est la chaleur qui s’en dégage, la passion. Cela nous rappelle la leçon du regretté Pierre Hadot, récemment décédé, qui n’avait de cesse de répéter que, pour les Anciens, c’est-à-dire finalement pour nous, le choix philosophique était un engagement existentiel.

18:27 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, philosophie grecque, christianisme, gnosticisme, antiquité tardive, antiquité grecque |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 22 octobre 2021

Aleksandr Douguine et la politique gnostique

Aleksandr Douguine et la politique gnostique

Cristian Barros

Qu'est-ce que le gnosticisme? La question est certainement aussi ancienne que le mouvement spirituel et intellectuel auquel elle fait allusion. Historiquement, le gnosticisme semble être la pénombre ésotérique, marginale, voire élitiste de la plupart des religions abrahamiques, et en tant que tel, il coule comme un courant sous-jacent dans les piétiés exotériques et officielles. Ses sources sont opaques et fragmentaires, et son portrait dépend largement des critiques hostiles, principalement chrétiennes, qui ont contribué à sa ruine. Les gnostiques ont vraisemblablement délibéré avec une grande véhémence sur l'origine du mal, dont découlerait une théogonie fondée sur l'aliénation de l'homme au cosmos. Leur métaphysique est dualiste: le mal et le bien coexistent, le premier étant identifié à la matière et le second à l'esprit. La relation entre les deux dimensions est hautement dramatique, et repose sur un acte de trahison ou d'usurpation. Ainsi, des gnostiques comme Marcion affirment que la fable de la Chute est en réalité une inversion profane du véritable secret du monde: le Serpent est le dispensateur de la lumière et le Dieu biblique une entité asservissante et jalouse.

Certains récits gnostiques soutiennent que la lutte entre le mal et le bien sera résolue dans un dénouement climatique, d'où les diverses apocalypses découvertes à Nag Hammadi (1). D'autres versions, en revanche, se désintéressent froidement du sort du monde actuel. Ce pessimisme radical accepte que le mal soit le tissu même de la réalité, échappant à toute rédemption.

Il est clair que nous avons affaire à une hétérodoxie qui est elle-même une tradition complexe offrant de multiples interprétations. Mais son caractère marginal, proprement initiatique, se prête assez mal à la constitution d'un horizon politique, surtout à l'ère de la politique de masse. Néanmoins, il convient de rappeler que nombre des mouvements politiques de la Modernité sont nés dans des contextes sectaires, voire conspirationnistes, des francs-maçons de 1789 aux ligues d'artisans de 1848. Pour paraphraser Carl Schmitt, on peut dire que les catégories de la politique moderne résultent de la sécularisation des motifs religieux. En effet, l'évidement même du sacré en Occident a déplacé les aspirations prophétiques de l'autel vers la tribune parlementaire et les bureaux bureaucratiques. De manière symptomatique, le bourgeois Bentham et le révolutionnaire Lénine reposent aujourd'hui encore momifiés dans leurs sanctuaires murés de cristal respectifs.

Le XXe siècle a vu réapparaître, cette fois plus que comme une simple curiosité de cabinet, l'ancienne gnose héritée d'Alexandrie et du Levant hellénistique. Je pense ici en particulier aux études d'Adolph von Harnack, un savant prussien qui a réhabilité la figure de l'hérésiarque Marcion dans son livre éponyme, Marcion : Le testament d'un Dieu étrange. Rétrospectivement, le texte de Harnack peut être considéré comme le renouvellement philologique des études gnostiques, celles-ci étant tacitement impliquées dans la polémique protestante. Harnack semble avoir fait de Marcion un véhicule pour sa critique du légalisme religieux sclérosé qui perdure dans le christianisme, une rigidité que Harnack impute finalement au judaïsme.

En effet, en tant que religion purement intérieure, une forme d'intériorité mystique, le gnosticisme était proche du piétisme luthérien, mais se distançait de ce dernier dans la mesure où le gnosticisme primitif promettait à l'initié un processus de déification intérieure ou théosis. En tout cas, la redécouverte du gnosticisme dans le romantisme allemand avait un aspect politique évident, concernant l'épuration des éléments orientaux ou pharisiens d'un nouveau credo d'authenticité autochtone. Marcion lui-même s'attaquait à la tendance pétrinienne et philosémite du christianisme du deuxième siècle, et visait ainsi à créer un Évangile purifié, idéalement exempt des stigmates du tribalisme et du ritualisme mosaïques.

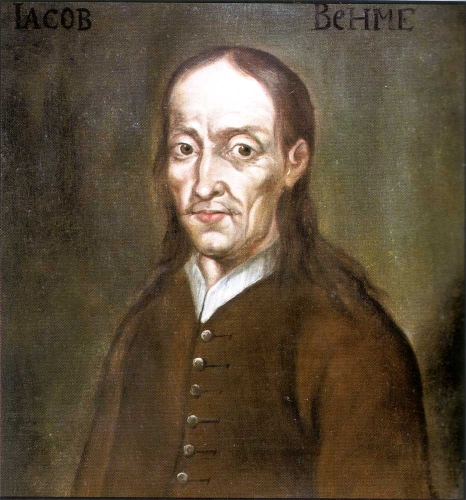

Bien sûr, la théosophie romantique peut être retracée jusqu'au visionnaire baroque autodidacte Jacob Boehme, qui influencera finalement Hegel, comme l'atteste solidement le livre notoire de F. C. Baur. D'ailleurs, le romantisme lui-même, en tant que rébellion contre la rationalité extérieure, antagoniste du légalisme universel jacobin, peut être comparé à une explosion instinctive des motifs antinomiens, ataviques, de la gnose : aliénation et authenticité, pessimisme métaphysique et héroïsme existentiel.

En ce sens, Hegel est un acteur majeur de ce que nous pouvons appeler la nébuleuse du gnosticisme moderne. Hegel a adapté les anciennes figures de l'histoire sacrée en langage académique, sécularisant la théorie même de la Trinité chrétienne dans sa dialectique, tout en masquant l'historicisme providentiel de Joachim de Fiore derrière sa téléologie idéaliste. D'une manière ou d'une autre, nous dit-on, Hegel a contribué au programme des futures religions politiques ou laïques et de leurs régimes subséquents, comme des chercheurs à l'esprit libéral comme Raymond Aron, Karl Popper et Eric Voegelin ont surnommé les expériences totalitaires du 20e siècle. En conséquence, nous pouvons considérer le siège de Stalingrad comme le choc apocalyptique des deux ailes opposées de la chimère hégélienne: l'universalisme marxiste et le particularisme nazi. Avec le temps, cependant, le camp triomphant allait connaître sa propre Némésis : la chute du mur de Berlin en 1989. Depuis lors, le pragmatisme libéral, dans son incarnation la plus nihiliste, récupère tout le butin du monde.

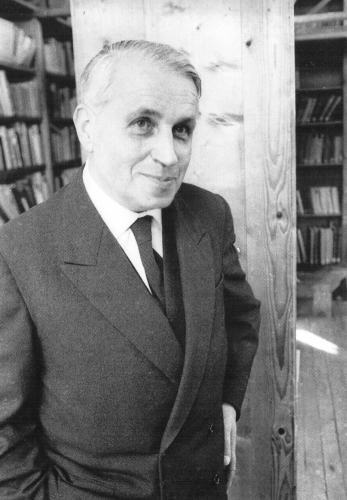

Il est révélateur que le professeur émigré de l'entre-deux-guerres Eric Voegelin ait inventé la thèse tant vantée de "l'immanentisation de l'Eschaton" afin d'anathématiser, plutôt que d'analyser sérieusement, l'émergence d'agendas totalisants ou révolutionnaires en politique. Voegelin se réfère ici à l'Eschaton comme à la consommation surnaturelle de l'histoire, déplorant la perversion démagogique qui transforme "la fin du temps sacré" en "le début d'une nouvelle ère profane". En vérité,

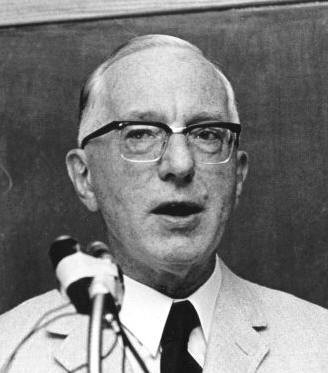

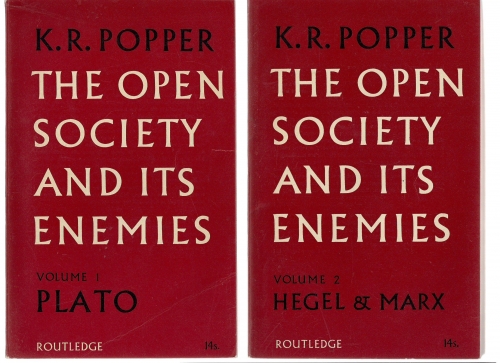

Voegelin tente d'exorciser l'infiltration de l'espérance chiliastique dans le statu quo bourgeois. Un effort similaire a également été déployé par un autre exilé libéral, Karl Popper, qui a rédigé le volumineux manifeste de la nouvelle foi antitotalitaire, La société ouverte et ses ennemis (1945), condamnant Platon et Hegel en tant que rêveurs d'une utopie spartiate, verticale et introvertie : la société fermée, un paradis du même.

En réalité, tous ces polémistes libéraux ont lutté contre l'intégration des masses, et donc de l'irrationnel, dans la politique moderne. Contrairement à eux, les essayistes antilibéraux comme Georges Bataille et Carl Schmitt voyaient les choses avec une sorte d'optimisme cryptique. Bataille, pornographe obscur, primitiviste bohème et saint manqué, a également été un brillant interprète de la nouvelle politique de masse tout au long des années trente. À cette époque, Bataille était profondément immergé dans l'hermétisme, au point de fonder le "Collège de sociologie sacrée", un cénacle cultuel visant à restaurer les rites sacrificiels dans les bois parisiens, une affaire sans doute extravagante. Pourtant, l'article en question, La structure psychologique du fascisme (1933), présente encore de puissantes intuitions nietzschéennes. En résumé, le texte considère le fascisme comme une résurgence de l'"hétérogène", l'étiquette de Bataille pour l'irrationnel et le refoulé: un magma qui monte du monde souterrain animal de la psyché humaine.

Bien que formellement communiste, le projet anthropologique de Bataille était créativement antimoderne, puisqu'il prétendait racheter l'aliénation de l'homme au moyen de liens sacrés comme le sexe et le jeu. De manière anecdotique, l'historien marxiste Richard Wolin considère Bataille comme un énergumène totalitaire, situé quelque part sur le spectre du national-bolchevisme. Notre point de vue est peut-être moins indulgent, puisque nous accusons Georges Bataille d'être un sombre gnostique, qui n'a fait que flirter avec le communisme et le fascisme en tant que stratégies terre-à-terre pour finalement inaugurer l'Eschaton.

Presque en chœur, maintenant sur l'autre rive du Rhin, le juriste Carl Schmitt a écrit son essai Staat, Bewegung, Volk, un sinistre chant du cygne pour le régime constitutionnel et parlementaire de Weimar, dont Schmitt ne pleure pas du tout l'agonie. En fait, Schmitt postule ici une identification dynamique entre masses et appareil d'État, voire le dépassement même de la technocratie par le peuple en armes. Également catholique ex-ultramontain comme Bataille lui-même, Schmitt fustige le marxisme universaliste tout en menaçant les capitalistes d'un futur État ouvrier populiste et plébiscitaire. Il va sans dire que la dénonciation de Marx par Schmitt concerne son libéralisme voilé, son universalisme abstrait, et non son élan prolétarien.

Par parenthèse, Schmitt était également un lecteur avide de l'hermétiste français René Guénon, une figure dont la gravitation était également très palpable dans le milieu de Bataille. De manière intrigante, une autre présence commune hantant le champ intellectuel de Schmitt et de Bataille est celle de Joseph de Maistre, l'ennemi juré de 1789, et pourtant son garant providentiel. La théorie du sacrifice de Maistre, qui remonte à Origène, peut-être le seul gnostique parmi les Pères de l'Église, résonne étrangement avec l'œuvre de Bataille et de Schmitt. D'une manière ou d'une autre, on pense naturellement à ces deux auteurs, ces deux maudits, mi-chanteaux mi-icônes de la contre-culture, lorsque Popper invoque les "ennemis" de la société ouverte...

Jusqu'à présent, un avatar récent de ce que nous pourrions appeler la politique gnostique est le polygraphe russe Alexandre Douguine, dépeint pendant ses années juvéniles par un romancier français contemporain comme un "ours dansant avec un sac à dos rempli de livres". Au-delà des digressions, Douguine a suffisamment mûri pour devenir un intellectuel antilibéral lucide et un prosélyte des blocs civilisationnels au-delà de l'esprit de clocher des petits États-nations. Souvent diabolisé comme un impérialiste russe, Douguine prône plutôt la création d'œcumènes ou de "grands espaces" en fonction des strates culturelles et religieuses. En conséquence, il pourrait être plus justement caractérisé comme un zélateur agissant contre l'impérialisme unipolaire, à savoir l'hégémonie atlantiste, que comme un simple bigot nostalgique du passé russe.

Bien au contraire. Douguine est un activiste acharné, un terroriste de l'esprit, et non un rat de bibliothèque mélancolique de la variété slave.

Tout bien considéré, Dugin est un penseur géostratégique et aussi un théoricien politique, mais ces appellations transcendent l'étiquette académique. Il ressemble à la fois à Bataille et à Schmitt dans la mesure où l'écriture exotérique masque un noyau ésotérique et anagogique plus profond. Encore une fois, il est plus un mystagogue qu'un érudit formel, bien qu'il accomplisse ce rôle de façon impeccable. Quant à Douguine, nous pouvons ajouter que la Tradition et la Révolution sont des pôles voués à être réconciliés dans un futur apogée, ce qui est une entreprise à laquelle il tient beaucoup.

Ainsi, son évolution du dissident soviétique au national-bolchevisme et à l'eurasianisme n'enlève rien à son noyau intérieur, qui est certainement gnostique et apocalyptique. En ce qui concerne sa première description, le "complexe national-bolchevisme" a toujours eu une dimension territoriale, visant à réaliser une entente continentale entre l'Allemagne et la Russie - comme un rempart contre l'étouffoir capitaliste atlantiste. Dès lors, l'eurasianisme de Douguine devient cohérent, un déploiement naturel. En outre, son "socialisme populiste" n'est pas abstrait mais historiquement enraciné, il n'est pas technophile mais plutôt tellurique, il s'appuie donc sur le développement organique des communautés établies. Quant à son eurasianisme, Douguine emprunte de manière transparente aux travaux de terrain de Lev Gumilev sur la symbiose entre agriculteurs et pasteurs dans les steppes, auxquels Gumilev attribuait un "zeste cyclique" (passionarnost) pour conquérir puis être à son tour assimilé à des structures sédentaires: des barbares revitalisant l'horizon agraire.

Une précision s'impose donc.

Certes, l'esprit grec faisait la distinction entre topos et chôra. Selon le Timée de Platon, par exemple, il y avait une véritable différence entre un point d'une extension abstraite, à savoir un crux cartographique, et le "lieu existentiel". Ainsi, la chôra était un espace d'enracinement, une réalité ancrée. Platon, quant à lui, considérait évidemment l'Attique, et plus particulièrement Athènes, comme son véritable lieu d'appartenance. C'est pourquoi l'exil politique, l'éviction de sa propre ville, était considéré comme pire que la mort, condition illustrée par le procès de Socrate. En revanche, le topos que l'on retrouve plus tard chez Aristote représente l'espace pur, le continuum quantitatif - qui se transformera finalement en res extensa de Descartes, le tableau physique et géométrique.

Il est révélateur que les Grecs classiques n'aient renoncé au patriotisme et embrassé le cosmopolitisme qu'une fois les cités hellénistiques vaincues par les légions romaines. Les besoins pratiques d'accommodement et de survie ont dicté un nouveau compromis, dès que la Grèce a été réduite au statut de colonie. Les philosophes s'adaptent progressivement à la domination impériale et, finalement, se divisent en deux écoles, l'une cynique et l'autre stoïcienne. Apparemment, Diogène le Cynique ("qui vivait comme un chien") fut le premier à inventer le terme kosmopolitês ("citoyen du monde"). Cette innovation subtile impliquait un changement radical par rapport au mythe traditionnel athénien de l'autochtonie, la croyance ancestrale partagée de descendre du sol même de la Grèce. Mais alors que les cyniques étaient plutôt des universalistes individualistes, les stoïciens étaient des organicistes cosmiques. En temps voulu, le stoïcisme est devenu la philosophie de l'oligarchie romaine, avec tout son fatalisme patricien et son sens du devoir déguisé en alibi pour la conquête.

L'espace en tant que quantité est finalement une aberration de la conscience, un phantasme-phénomène mathématique exacerbé plus tard par le commerce et la science moderne. Heureusement, l'écologie, en tant que "science holistique", est apparue dans les années 1900 comme un antidote opportun contre cette vision positiviste, technocentrique et réductionniste. De même, on pourrait citer ici les résultats de l'éthologie et de la géographie humaine de Jacob von Uexküll à Auguste Berque, et même des "écologistes culturels" comme Leo Frobenius, qui ont respectivement abordé l'interaction environnementale en utilisant des notions empathiques et contextuelles comme Umwelt, oecumène et Paideuma.

Douguine lui-même défend la notion de Heidegger du Dasein en tant que lieu d'être organique, enraciné et historiquement significatif. Heidegger célèbre la surface plutôt que la profondeur, l'impression quotidienne plutôt que la théorie incarnée, la routine inconsciente plutôt que l'effort délibéré, et il crée ainsi une sorte de populisme existentiel: "Être, c'est habiter". En conséquence, l'appropriation par Douguine de ce motif heideggérien lui permet de construire un projet géopolitique totalisant, qui repose à la fois sur le localisme et le pluralisme.

Cependant, la vision finale du monde de Douguine concerne les polities géostratégiques ou les "blocs civilisationnels". Plus encore, Dugin postule qu'un esprit transcendant ou un "ange" surplombe chaque civilisation, ce qui essentialise fortement sa théorie des relations internationales. Néanmoins, l'angélologie politique de Douguine permet une lecture métaphorique fructueuse - un exercice également proposé par Giorgio Agamben, un schmittien de gauche. Maintenant, pour récapituler, je souligne l'endroit même où Douguine affirme sa singularité, en habitant un paysage posthistorique - pour ainsi dire, une arène eschatologique.

En tant que gnostique, Douguine est un dualiste métaphysique et comprend que la lutte finale, en tant que point culminant d'une série d'escarmouches mineures, est exclusivement binaire, littéralement manichéenne. À ce stade, la fin du temps terrestre devient donc le début du temps sacré. De même, l'espace du conflit devient lui aussi sacralisé, c'est-à-dire orienté vers le sacrifice et la mort. Les anges de la fin s'incarnent dans les puissances de la Mer et de la Terre, thalassocratie contre tellurocratie, Léviathan contre Béhémoth... En d'autres termes, il s'agit de cultures mobiles contre des cultures axiales, ces dernières étant amalgamées dans la masse eurasienne, appelée Heartland.

16:41 Publié dans Nouvelle Droite, Philosophie, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : alexandre douguine, nouvelle droite, nouvelle droite russe, philosophie, philosophie politique, théologie politique, gnosticisme, tradition, traditionalisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 20 février 2013

Know Your Gnostics

Know Your Gnostics

Eric Voegelin diagnosed the neoconservatives' disease

Eric Voegelin often is regarded as a major figure in 20th-century conservative thought—one of his concepts inspired what has been a popular catchphrase on the right for decades, “don’t immanentize the eschaton”—but he rejected ideological labels. In his youth, in Vienna, he attended the famous Mises Circle seminars, where he developed lasting friendships with figures who would be important in the revival of classical liberalism, such as F.A. Hayek, but he later rejected their libertarianism as yet another misguided offshoot of the Enlightenment project. Voegelin has sometimes been paired with the British political theorist Michael Oakeshott, who greatly admired his work, but he grounded his political theorizing in a spiritual vision in a way that was quite foreign to Oakeshott’s thought. Voegelin once wrote, “I have been called every conceivable name by partisans of this or that ideology… a Communist, a Fascist, a National Socialist, an old liberal, a new liberal, a Jew, a Catholic, a Protestant, a Platonist, a neo-Augustinian, a Thomist, and of course a Hegelian.”

But whatever paradoxes he embodied, Voegelin was, first and foremost, a passionate seeker for truth. He paid no attention to what party his findings might please or displease, and he was willing to abandon vast amounts of writing, material that might have enhanced his reputation as scholar, when the development of his thought led him to believe that he needed to pursue a different direction. As such, his ideas deserve the attention of anyone who sincerely seeks for the origins of political order. And they have a timely relevance given recent American ventures aimed at fixing the problems of the world through military interventions in far-flung regions.

Voegelin was born in Cologne, Germany in 1901. His family moved to Vienna when he was nine, and there he earned a Ph.D. in political science in 1922, under the dual supervision of Hans Kelsen, the author of the constitution of the new Austrian republic, and the economist Othmar Spann. He subsequently studied law in Berlin and Heidelberg and spent a summer at Oxford University mastering English. (He commented that his English was so poor when he arrived that he spent some minutes wondering why a street-corner speaker was so enthusiastic about the benefits of cheeses, before he realized the man was preaching about Jesus.) He then traveled to the United States, where he took courses at Columbia with John Dewey, Harvard with Alfred North Whitehead, and Wisconsin with John R. Commons, where he said he first discovered “the real, authentic America.”

Upon returning to Austria, he resumed attending the Mises Seminar, and he published two works critical of the then ascendant doctrine of racism. These made him a target of the Nazis and led to his dismissal from the University of Vienna after the Anschluss. As with many other Austrian intellectuals, the onslaught of Nazism made him leave Austria. (He and his wife managed to obtain their visas and flee to Switzerland on the very day the Gestapo came to seize his passport.) Voegelin eventually settled at Louisiana State University, where he taught for 16 years, before coming full circle and returning to Germany to promote American-style constitutional democracy in his native land. The hostility generated by his declaration that the blame for the rise of Nazism could not be pinned solely on the Nazi Party elite, but must be shared by the German people in general, led him to return to the United States, where he died in 1985.

During his lifelong search for the roots of social order, Voegelin came to understand politics not as an autonomous sphere of activity independent of a nation’s culture, but as the public articulation of how a society conceives the proper relationship of its members both to one another and to the rest of the cosmos. Only when a society’s political institutions are an organic product of a widely shared and existentially workable conception of mankind’s place in the universe will they successfully order social life. As a corollary of his understanding of political life, Voegelin rejected the contemporary, rationalist faith in the power of “well-designed,” written constitutions to ensure the continued existence of a healthy polity. He argued that “if a government is nothing but representative in the constitutional sense, a [truly] representational ruler will sooner or later make an end of it… When a representative does not fulfill his existential task, no constitutional legality of his position will save him.”

For Voegelin, a truly “representative” government entails, much more crucially than the relatively superficial fact that citizens have some voice in their government, first of all that a government addresses the basic needs of “securing domestic peace, the defense of the realm, the administration of justice, and taking care of the welfare of the people.” Secondly, a political order ought to represent its participants’ understanding of their place in the cosmos. It may help in grasping Voegelin’s meaning here to think of the Muslim world, where attempts to create liberal, constitutional democracies can result in Islamic theocracies instead: the first type of government is “representative” in the narrow, constitutional sense, while the second actually represents those societies’ own understanding of their place in the world.

Voegelin undertook extensive historical analysis to support his view of the representative character of healthy polities, analysis that appeared chiefly in his great, multi-volume works History of Political Ideas—which was largely unpublished during Voegelin’s life because his scholarship prompted him to change the focus of his research—and Order and History. This undertaking was more than merely illustrative of his ideas, since he understood political representation itself not as a timeless, static construct but as an ongoing historical process, so that an adequate political representation for one time and place will fail to be representative in a different time or for a different people.

The earliest type of representation Voegelin described is that characterizing the ancient “cosmological empires,” such as those of Egypt and the Near East. Their imperial governments succeeded in organizing those societies for millennia because they were grounded in cosmic mythologies that, while containing cyclical phenomena like day and night and the seasons, depicted the sequence of such cycles as eternal and unchanging. They “symbolized politically organized society as a cosmic analogue… by letting vegetative rhythms and celestial revolutions function as models for the structural and procedural order of society.”

The sensible course for members of a society with such a self-understanding was to reconcile themselves to their fixed roles in the functioning of this implacable, if awe-inspiring, universe. The emperor or pharaoh was a divine being, the representative for his society of the ruling god of the cosmic order, and as remote and unapproachable as was that god. The demise of the cosmological empires in the Mediterranean world came with Alexander the Great’s conquests. After his empire was divided among his generals following his death, the new monarchs could not plausibly claim the divine mandate that native rulers had asserted as the basis of their authority since their ascension was so clearly based on military conquest and not on some ancient act of a god seeking to provide the now-conquered peoples with a divine guide.

The basis of the Greek polis was the Hellenic pantheon. When the faith in that pantheon was undermined by the work of philosophers, the polis ceased to be a viable form of polity, as those resisting its passing recognized when they condemned Socrates to death for not believing in the civic gods. The Romans, a people not generally prone to theoretical speculation, managed to sustain their republican city-state model of politics far longer than had the Greeks but eventually the stresses produced by the spoils of possessing a vast empire and the demands of ruling it—as well as the increasing influence of Greek philosophical thought in Rome—proved fatal to that republic as well.

Mediterranean civilization then entered a period of crisis characterized by cynical, imperial rule by the Roman emperors and an urgent search for a new ordering principle for social existence among their subjects, which produced the multitude of cults and creeds that proliferated during the imperial centuries. The crisis was finally resolved when Christianity, institutionalized in the Catholic Church, triumphed as the new basis for organizing Western society, while the Orthodox Church, centered in Constantinople, played a similar role in the East.

Voegelin contends that this medieval Christian order began to fracture due to the de-spiritualization of the Church that resulted from its increasing focus on power over secular affairs. Having succeeded in restoring civil order to Western Europe during the several centuries following the fall of Rome, the Church would have done best, as Voegelin saw it, to have withdrawn voluntarily “from its material position as the greatest economic power, which could be justified earlier by the actual civilizing performance.” Furthermore, the new theories of natural philosophy produced by the emerging “independent, secular civilization… required a voluntary surrender on the part of the Church of those of its ancient civilizational elements which proved incompatible with the new Western civilization… [but] again the Church proved hesitant in adjusting adequately and in time.”

The crisis caused by the Church’s failure to adjust its situation to the new realities came to a head with the splintering of Western Christianity during the Protestant Reformation and the ascendancy of the authority the nation-state over that of the Church.

The newly dominant nation-states energetically and repeatedly attempted to create novel myths that could ground their rule over their subjects. But these were composed from what Voegelin called “hieroglyphs,” superficial invocations of a pre-existing concept that failed to embody its essence because those invoking it had not themselves experienced the reality behind the original concept. As hieroglyphs, the terms were adopted because of the perceived authority they embodied. But as they were being employed without the context from which their original validity arose, none of these efforts created a genuine basis for a stable and humane order.

The perception of the hollow core of the new social arrangements became the motivation for and the target of a series of modern utopian and revolutionary ideologies, culminating in fascism and communism. These movements evoked what had been living symbols for medieval Europe—such as “salvation,” “the end times,” and the “communion of the saints”—but as the revolutionaries had lost touch with the spiritual foundation of those symbols, they perverted them into political slogans, such as “emancipation of the proletariat,” “the communist utopia,” and “the revolutionary vanguard.”

This analysis is the source of the phrase “immanentize the eschaton”: as Voegelin understood it, these revolutionary movements had mistaken a spiritual symbol, that of the ultimate triumphant kingdom of heaven (the eschaton), for a possible goal of mundane politics, and they were attempting to create heaven on earth (the immanentizing) through revolutionary action. He sometimes described this urge to create heaven on earth by political means as “Gnostic,” especially in what remains his most popular work, The New Science of Politics. (Voegelin later came to question the historical accuracy of his choice of terminology.)

But communism and fascism were not the only options on the table when Voegelin was writing: the constitutional liberal democracies, especially those of the Anglosphere, resisted the revolutionary movements. While Voegelin was not a modern liberal, his attitude towards these regimes was considerably more sympathetic than it was towards communism or fascism. He saw certain tendencies in the Western democracies, such as the near worship of material well-being and the attempted cordoning off of religious convictions into a purely private sphere, as symptoms of the spiritual crisis unfolding in the West. On the other hand, he believed that in places like Britain and the United States there had been less destruction of the West’s classical and Christian cultural foundations, so that the liberal democracies had retained more cultural resources with which to combat the growing disorder than was present elsewhere in Europe.

As a result, he firmly supported the liberal democracies in their effort to resist communism and fascism, and his return to Germany after the war was prompted by the hope of promoting an American-inspired political system in his native land. We can best understand Voegelin’s attitude towards liberal democracy as being, “Well, this is the best we can do in the present situation.”

He saw the pendulum of order and decay as always in motion, and he was convinced that one day a new cosmology would arise that would be the basis for a new civilizational order. In the meantime, the Western democracies had at least worked out a way for people with profoundly divergent understandings of their place in the cosmos to live decently ordered lives in relative peace. Always a realist, Voegelin was not one to look down his nose at whatever order it is really possible to achieve in our actual circumstances.

But the liberal democracies are liable to fall victim to their own form of “immanentizing the eschaton” if they mistake the genuinely admirable, albeit limited, order they have been able to achieve for the universal goal of all history and all mankind. That error, I suggest, lies behind the utopian adventurism of America’s recent foreign policy, in both its neoconservative and liberal Wilsonian forms. Voegelin’s analysis of “Gnosticism” can help us to understand better the nature of that tendency in Western foreign policy. (We can still use his term “Gnostic” while acknowledging, as he did, its questionable historical connection to ancient Gnosticism.)

Voegelin was no pacifist—for instance, he was committed to the idea that the West had a responsibility to militarily resist the expansive barbarism of the Soviet Union. Yet it is unlikely that he would have had any patience for the utopian Western triumphalism often exhibited by neoconservatives and Wilsonians.

What Voegelin called “the Gnostic personality” has great difficulty accepting that the impermanence of temporal existence is inherent in its nature. Therefore, as he wrote, the Gnostic seeks to freeze “history into an everlasting final realm on this earth.” The common view that any nation not embracing some form of liberal, constitutional democracy is in need of Western re-education, by force if necessary, and the consequent fixation on installing such regimes wherever possible, displays a faith that we in the West have achieved the pinnacle of social arrangements and should “freeze history.”

One of the chief vices Voegelin ascribes to Gnosticism is the will to live in a dream world and the reluctance to allow reality to intrude upon the dream. During the many years of chaotic violence following America’s “victory” in Iraq, the difficulty of continuously evading the facts on the ground compelled some who supported the war to admit that things did not proceed as envisioned in their prewar fantasy. Even so, few of these reluctant realists are moved to concede that launching the war was a mistake. A popular dodge they engage in is to ask critics, “So, you’d prefer it if Hussein was still in power and still oppressing the Iraqi people?”

That riposte assumes that, if a goal is laudable when evaluated in a vacuum from which contraindications have been eliminated, then pursuing it is fully justified. Unfortunately, as the post-invasion years in Iraq demonstrate, it was quite possible to depose Hussein while creating greater misfortunes for Iraqis. The Western moral tradition developed primarily by the Greek philosophers and Christian theologians denied that a claim of good intentions was a sufficient defense of the morality of an action. This tradition held that anyone seeking to pursue the good was obligated to go further, giving as much prudent consideration to the likely ramifications of a choice as circumstances allowed.

But in the Gnostic dream world, the question of whether the supposed beneficiaries of one’s virtuously motivated crusade realistically can be expected to gain or lose as a result of it is dismissed as an unseemly compromise with reality. What matters to the Gnostic revolutionary is that his scheme intends a worthy outcome; that alone justifies undertaking it. Such contempt for attending to the messy and complex circumstances of the real world is exemplified in the account of George W. Bush’s foreign policy that one of his advisers provided to a puzzled journalist, Ron Suskind, who described their encounter in the New York Times Magazine:

The aide said that guys like me were ‘in what we call the reality-based community,’ which he defined as people who ‘believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality.’ I nodded and murmured something about enlightenment principles and empiricism. He cut me off. ‘That’s not the way the world really works anymore,’ he continued. ‘We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality—judiciously, as you will—we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors… and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.’

As it became obvious that their Iraq adventure was not living up to its promise of rapidly and almost without cost producing a stable, democratic, and pro-Western regime in the midst of the Arab world, supporters of the war were loath to entertain the possibility that its failure was due to their unrealistic understanding of the situation. Instead, they often sought to place the blame on the shortcomings of those they nobly had attempted to rescue, namely, the people of Iraq. Voegelin had noted this Gnostic tendency several decades earlier: “The gap between intended and real effect will be imputed not to the Gnostic immorality of ignoring the structure of reality but to the immorality of some other person or society that does not behave as it should according to the dream conception of cause and effect.”

Much more could be said concerning the relevance of Voegelin’s political philosophy to our recent foreign policy, but the brief hints offered above should be enough to persuade those open to such realistic analysis to read The New Science of Politics and draw further conclusions for themselves.

While it is true that Voegelin resisted being assigned to any ideological pigeonhole, there are important aspects of his thought that are conservative in nature. He rejected the notion, sometimes present in romantic conservatism, that the solution to our present troubles can lie in the recreation of some past state of affairs: he was too keenly aware that history moves ever onward, and the past is irretrievably behind us, to fall prey to what we might call “nostalgic utopianism.” Nevertheless, he held that our traditions must be studied closely and adequately understood because, while it is nonsensical to try to duplicate the past, still it is only by understanding the insights achieved by our forebears that we can move forward with any hope of a happy outcome.

While historical circumstances never repeat, Voegelin understood human nature and its relation to the eternal to create a similar ground in all times and places, an insight that surely is at the core of any genuine conservatism. Thus, it is our task to recreate, in our own minds, the brilliant advances in understanding the human condition that were achieved by such figures as Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, and Aquinas. Those advances serve as the foundation for our efforts to respond adequately to the novel conditions of our time. Voegelin’s message is one that any thoughtful conservative must try heed.

Gene Callahan teaches economics at SUNY Purchase and is the author of Oakeshott on Rome and America.

00:05 Publié dans Philosophie, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : eric voegelin, théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques, philosophie, états-unis, gnosticisme, gnoses, gnoses politiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook