samedi, 28 mai 2022

Au-delà du "gauchisme": le fléau "trotskyste" dans les mouvements contre-hégémoniques

Au-delà du "gauchisme": le fléau "trotskyste" dans les mouvements contre-hégémoniques

Tácio Nepomuceno Reis

Source: https://novaresistencia.org/2022/05/20/para-alem-do-esquerdismo-a-chaga-trotskista-nos-movimentos-contra-hegemonicos/

Il est possible d'affirmer avec force conviction que le vingtième siècle a représenté le scénario de la plus grande polarité idéologique de l'histoire de l'humanité. Même si nous comprenons que d'autres questions géopolitiques fondamentales ont dicté les orientations de cette polarité, le poids des idées qui se sont affrontées à cette époque est indéniable. En ce sens, il est également notable que ces paradigmes idéologiques du passé reflètent encore le modus operandi de nombreuses organisations politiques à notre époque, ce qui rend nécessaire la compréhension de ces problèmes pertinents, et de nature idéologique, pour les organisations contre-hégémoniques dans le monde.

La gauche communiste, d'héritage bolchevique, a posé un jalon important au vingtième siècle au sein des paradigmes politiques contre-hégémoniques. Bien qu'elle constituait un pôle hégémonique dans sa sphère d'influence, l'Union soviétique représentait, pour la grande majorité des mouvements dissidents et révolutionnaires du monde entier, un pilier contre-hégémonique. Ceci pour des raisons évidentes. La ligne stalinienne a établi une URSS terrestre, qui pouvait facilement être comprise comme un contrepoint au pôle maritime dirigé par les États-Unis, beaucoup plus négativement ressenti par les peuples du tiers monde que leur rival rouge.

Dans cette logique, il est possible d'observer dans l'histoire des mouvements dissidents de l'après-Seconde Guerre mondiale une nette tendance à la "soviétisation", à l'acceptation des paradigmes soviétiques comme moyen de s'établir en tant qu'organisation contre-hégémonique dans l'espace de pouvoir américain. Ce comportement a mis en évidence une question fondamentale pour la lutte contre l'hégémonie: la nécessité de renforcer d'autres pôles de pouvoir comme moyen de disperser le pouvoir centralisé de la puissance hégémonique ennemie. En ce sens, il est remarquable que la plupart des soulèvements populaires et dissidents les plus pertinents de la seconde moitié du vingtième siècle soient basés sur une lecture de la géopolitique soviétique, même s'ils avaient des racines traditionnelles différentes. Il est possible de se souvenir de la Corée populaire, de Cuba, du Vietnam, de la lutte pour l'indépendance de plusieurs pays africains et de la résistance latino-américaine. Dans la grande majorité de ces processus, la question nationale était la flamme initiale de la révolution, qui cherchait à se consumer sur les piliers mondiaux qui lui permettaient d'établir sa résistance contre son ennemi le plus immédiat : les États-Unis d'Amérique et les puissances coloniales d'Europe occidentale.

Malgré cette compréhension correcte qui a conduit au succès de plusieurs groupes dissidents à travers le monde dans leur lutte contre l'impérialisme américain, il y a toujours eu l'émergence constante de groupes fragmentaires ancrés dans un idéal de purisme idéologique, ignorant les conditions réelles de la géopolitique dissidente. C'est surtout au sein des mouvements communistes qu'ont émergé les "trotskystes". Léon Trotsky était un marxiste révolutionnaire qui, entre autres contributions théoriques au marxisme, a représenté la première opposition majeure au sein du parti bolchevik dans la période post-Lénine. Léon Trotsky a mis en avant une ligne "plus marxiste" au détriment d'une ligne "plus nationale" adoptée par Josef Staline. C'était une façon de chercher à préserver les acquis de la révolution russe, de fortifier son propre État plutôt que d'appliquer la vision marxiste d'une soi-disant révolution mondiale.

Trotsky, cependant, n'a pas péché que dans les idées. Son problème central réside dans la manière dont il s'est imposé en tant qu'opposant. Le principe du mode d'organisation léniniste est le centralisme démocratique, qui établit l'unité de la majorité au sein du parti. Trotsky réagit à ses défaites au sein du parti communiste et fonda un mouvement international antisoviétique, qui sera établi jusqu'à aujourd'hui avec les partisans de la "Quatrième Internationale". Dans la pratique, le trotskisme a cherché à transformer la dissidence antilibérale en une dissidence antisoviétique, à décentraliser les mouvements communistes à l'ère du centralisme, en ignorant le niveau complexe des relations géopolitiques établies à cette époque.

Alors, il est important de se demander : dans quelle mesure serait-il raisonnable d'imaginer un Vietnam, un Cuba, une Corée basés sur des idées trotskystes ? Serait-il assez réaliste d'imaginer que Fidel Castro refuse l'aide soviétique parce qu'il n'était tout simplement pas communiste dans ses premières années de révolution ? Évidemment non ! Le trotskisme, en tant que dissidence dans la dissidence, servait au fond les intérêts occidentaux de fragmentation et d'affaiblissement de la gauche, en lui retirant son principal allié dans la géopolitique des idées du 20ème siècle : l'URSS ! Le trotskisme (en tant que mouvement) était naïf, il croyait en la fatalité dépassée du matérialisme historique. Elle croyait être dissidente et omettait de se situer stratégiquement dans le contexte géopolitique de l'époque. Ce comportement n'a qu'un seul réflexe: les trotskystes n'ont jamais réussi à accéder au pouvoir, contrairement aux mouvements nationaux qui ont compris le rôle central de l'URSS dans le contrepoids international du pouvoir.

Mais après tout, que signifie tout cela encore aujourd'hui ? Il est curieux de méditer sur l'idée qu'aujourd'hui au Brésil, par exemple, il y a plus de partis "communistes" au siècle du communisme. Plus ils s'éloignent du pouvoir, plus les communistes se fragmentent en idéaux puristes (au sens marxiste) et plus ils s'éloignent de la géopolitique. Il était et il est toujours très difficile pour les mouvements de gauche de comprendre le bon équilibre des pouvoirs dans le monde. Il est difficile pour ces mouvements de comprendre l'idée qu'être contre-hégémonique, c'est aussi être pro-actif pour faire advenir de nouvelles hégémonies ayant la capacité de dissuader le pouvoir centralisateur d'une hégémonie unipolaire. Ce problème central n'est pas exclusif à la gauche communiste, qui a longtemps baigné dans cette logique. Elle a affecté la grande majorité des mouvements contre-hégémoniques en général. On peut voir, par exemple, la difficulté de la "droite" contre-hégémonique à reconnaître la pertinence de la Chine, ainsi que celle de la "gauche" à reconnaître le rôle de la Russie.

Le rôle de ces deux superpuissances aujourd'hui ne diffère pas beaucoup du rôle que jouait l'Union soviétique pour les pays du tiers monde pendant la guerre froide: le potentiel d'affronter l'ennemi en commun. Était-il possible d'être un Brésilien contre l'hégémonie des États-Unis sans défendre le rôle de l'URSS (il ne s'agit pas de communisme, mais de géopolitique !)? Y a-t-il un moyen d'être brésilien, dissident et contre-hégémonique sans défendre le rôle de la Russie dans un nouveau rééquilibrage des pouvoirs dans le monde ? Pour les trotskystes, en théorie et en esprit, c'est supposé l'être. Ils croient fidèlement qu'il est possible de mener une lutte dissidente en dehors des hiérarchies du pouvoir dans le monde. Les Chinois, les Cubains, les Coréens, les Iraniens, les Vietnamiens, entre autres, ont précisément réussi à définir correctement ce que signifie le pouvoir du prince.

Pour nous, Brésiliens dissidents, une lecture correcte des rapports de force dans le monde est de la plus haute importance. Si des pôles se mettent en place dans le monde pour s'opposer à l'hégémonie qui nous opprime, il faut s'allier brutalement avec eux ! Kim Il Sung, par exemple, n'a pas gaspillé son brio à critiquer les réformes de marché chinoises ; au contraire, il s'est centré sur la Corée afin de soutenir fermement le succès chinois en tant qu'étape cruciale dans le maintien de la révolution coréenne, même s'il n'était pas d'accord avec les méthodes de marché. De même, Fidel a toléré une URSS qui, à bien des égards, ne dialoguait pas dans la même langue que les révolutionnaires cubains. Il est remarquable que la lutte dissidente et contre-hégémonique réussie sache à l'avance qui sont ses ennemis et qui sont leurs ennemis. Les trotskystes et autres sectaires diviseurs ont défendu et défendent encore la conception d'être le seul et unique soleil capable de sortir le peuple de l'obscurité hégémonique occidentale, ignorant complètement la réalité géopolitique et les rapports de force dans le monde. Toutefois, il est facile de comprendre comment naissent de telles conceptions, qui n'étaient autrefois formulées qu'au sein des universités et des congrès, loin de la réalité complexe et progressive de la société.

Lorsque l'on a un objectif véritablement révolutionnaire, dissident et contre-hégémonique, il n'y a pas de temps pour les divisions et les purismes incompatibles avec la réalité. La construction du monde multipolaire passe directement par le soutien que chaque pôle non hégémonique apporte aux autres pour son établissement en tant que source souveraine de pouvoir. La victoire de tous les pôles de pouvoir ennemis de l'unipolarité occidentale est la victoire de la souveraineté brésilienne !

Le trotskisme est la maladie infantile de la dissidence !

18:37 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, communisme, idéologie, trotskisme, contre-hégémonisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 18 novembre 2020

La democracia del miedo y la ingenuidad

La democracia del miedo y la ingenuidad

En 1938 a un año de terminar la Guerra Civil española, el coronel del KGB Leonid Eitingon, empezó a formar con su colaboradora Caridad del Río Mercader (foto), comunista catalana y madre de Ramón Mercader del Río, un equipo de asesinos controlados por el Trust o sección exterior de la inteligencia soviética.

En 1938 a un año de terminar la Guerra Civil española, el coronel del KGB Leonid Eitingon, empezó a formar con su colaboradora Caridad del Río Mercader (foto), comunista catalana y madre de Ramón Mercader del Río, un equipo de asesinos controlados por el Trust o sección exterior de la inteligencia soviética.

En realidad fue Roberto Sheldon Harte, que era uno de los infieles pistoleros de Trotski, un recién llegado que había sido reclutado en Nueva York por el dirigente del grupo sionista Socialist Workers Party, Joseph Hansen, a quien el portal World Socialist Web Site puso en evidencia como agente del FBI, lo mismo que a su esposa Rebeca.

En realidad fue Roberto Sheldon Harte, que era uno de los infieles pistoleros de Trotski, un recién llegado que había sido reclutado en Nueva York por el dirigente del grupo sionista Socialist Workers Party, Joseph Hansen, a quien el portal World Socialist Web Site puso en evidencia como agente del FBI, lo mismo que a su esposa Rebeca. El libro de la destacada escritora costarricense Marjorie Ross, mencionado en este subtítulo, tiene de todo, incluidas las respuestas cruciales a las preguntas que se hicieron en todos los países los enterados de las discrepancias entre los dos beneficiarios eventuales de cara al poder que dejaría vacante Lenin al morir y que fueron mencionados en su “testamento”. Lenin destacó la inclinación de Trotski por el aspecto administrativo de los asuntos, y de Stalin su deslealtad y su poca delicadeza en el tratamiento de sus camaradas.

El libro de la destacada escritora costarricense Marjorie Ross, mencionado en este subtítulo, tiene de todo, incluidas las respuestas cruciales a las preguntas que se hicieron en todos los países los enterados de las discrepancias entre los dos beneficiarios eventuales de cara al poder que dejaría vacante Lenin al morir y que fueron mencionados en su “testamento”. Lenin destacó la inclinación de Trotski por el aspecto administrativo de los asuntos, y de Stalin su deslealtad y su poca delicadeza en el tratamiento de sus camaradas.

08:38 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : histoire, communisme, trotskisme, services soviétiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 04 février 2015

Trotskisme yankee et invention du néo-conservatisme

Trotskisme yankee et invention du néo-conservatisme

Qui sont les « néoconservateurs » américains et occidentaux ? Historique du mouvement issu du trotskisme en gardant présent à l’esprit que Trotski, tout comme Lénine, était un agent de Wall Street et de la City de Londres. Voir à ce sujet notre dossier sur « Wall Street et la révolution bolchévique » de l’historien Antony Sutton. Ceci nous éclaire sur le pourquoi capitalisme et capitalisme d’état (marxisme et ses variantes léniniste, trotskiste, staliniste, puis plus tard maoïste…) sont les deux côtés de la même pièce capitaliste, pilotés par les mêmes intérêts convergents de la haute finance et de l’industrie transnationale. Le mouvement trotskiste néoconservateur n’en est qu’un des avatars supplémentaire…

En France, Jospin et Cambadélis (entre autres) issus du mouvement « lambertiste », en sont les représentants de longue date…

À partir de 1945, les services de propagande états-uniens et britanniques recrutent des intellectuels souvent issus des milieux trotskistes afin d’inventer et promouvoir une « idéologie rivalisant avec le communisme ». Les New York Intellectuals, Sidney Hook (photo) en tête, accomplissent différentes missions confiées par la CIA avec zèle et efficacité, devenant rapidement des agents de premier plan de la Guerre froide culturelle. Des théoriciens majeurs de ce mouvement, comme James Burnham et Irving Kristol, ont élaboré la rhétorique néo-conservatrice sur laquelle s’appuient aujourd’hui les faucons de Washington.

À partir de 1945, les services de propagande états-uniens et britanniques recrutent des intellectuels souvent issus des milieux trotskistes afin d’inventer et promouvoir une « idéologie rivalisant avec le communisme ». Les New York Intellectuals, Sidney Hook (photo) en tête, accomplissent différentes missions confiées par la CIA avec zèle et efficacité, devenant rapidement des agents de premier plan de la Guerre froide culturelle. Des théoriciens majeurs de ce mouvement, comme James Burnham et Irving Kristol, ont élaboré la rhétorique néo-conservatrice sur laquelle s’appuient aujourd’hui les faucons de Washington.

En 1945, les stratèges soviétiques veulent obtenir la reconnaissance des démocraties populaires de l’Europe de l’Est. Ils lancent, en s’appuyant sur les services secrets, une campagne internationale pour la paix. Leur objectif est de conserver le contrôle du « glacis défensif » en évitant une série de conflits armés avec la coalition anglo-saxonne. En Grande-Bretagne, les gouvernements, notamment celui de Clement Attlee, cherchent à rompre avec la propagande de guerre qui a justifié de 1942 à 1945 l’alliance avec Moscou. Dans ce contexte, en février 1948, Attlee crée, au sein du Foreign Office, le Département de recherche de renseignements (IRD), véritable « ministère de la Guerre froide » alimenté par les fonds secrets et chargé de produire de fausses informations pour discréditer les communistes. Aux États-Unis, la situation est plus favorable. Les procès de Moscou, l’exil de Trotski, ancien bras droit de Lénine, et le pacte germano-soviétique ont considérablement nui au Parti communiste. Dans ce contexte, les marxistes rejoignent massivement l’aile trotskiste de la gauche radicale dont une fraction pactisera avec la CIA, trahissant la IVe Internationale. Après une série d’échecs désastreux, les services soviétiques renoncent à toute influence idéologique aux États-Unis et privilégient les pays d’Europe de l’Ouest, spécialement la France et l’Italie.

Les services secrets britanniques et états-uniens cherchent à fabriquer une pensée assez crédible et universelle pour rivaliser avec le marxisme-léninisme. Dans ce contexte, les New York Intellectuals – Sidney Hook, James Burnham, Irving Kristol, Daniel Bell…- vont constituer des combattants culturels particulièrement efficaces.

Les premiers « coups tordus »

Les New York Intellectuals n’ont pas besoin d’infliltrer les milieux communistes : ils s’y trouvent déjà et s’y définissent comme militants trotskistes. La CIA, en recrutant des hommes comme le philosophe marxiste Sidney Hook, collecte des renseignements utiles sur la gauche radicale états-unienne et tente de saboter les réunions internationales parrainées par Moscou.

En mars 1949, à New York, se tient une « conférence scientifique et culturelle pour la paix mondiale », à l’hôtel Waldorf Astoria. Des délégations de militants communistes s’y pressent ; la réunion est secrètement supervisée par le Kominform. Mais l’hôtel est sous contrôle de la CIA, qui y a installé un quartier général secret au dixième étage. Sidney Hook, qui joue le communiste repenti, reçoit à part des journalistes auxquels il explique « sa » stratégie contre « les staliniens » : intercepter le courrier du Waldorf et diffuser de faux communiqués. Profitant de la « position de cheval de Troie » de Sidney Hook, la CIA mène une campagne d’intoxication médiatique allant jusqu’à divulguer publiquement l’appartenance politique de certains participants préfigurant ainsi la « chasse aux sorcière » du sénateur McCarthy. Avec zèle et brio, Hook mène son équipe d’agitateurs, de délateurs et de manipulateurs, rédigeant des tracts et semant le désordre lors des tables rondes… Simultanément, à l’extérieur de l’hôtel Waldorf, des dizaines de militants d’extrême-droite défilent pancarte à la main pour dénoncer l’ingérence du Kominform. L’opération est un succès total, la conférence tourne au fiasco. ?Tirant les leçons du « coup du Waldorf », la CIA états-unienne et l’IRD britannique systématisent l’enrôlement de trotskistes dans la lutte secrète contre Moscou, au point d’en faire une constante de la « guerre psychologique » qu’ils livrent à l’URSS.

En mars 1949, à New York, se tient une « conférence scientifique et culturelle pour la paix mondiale », à l’hôtel Waldorf Astoria. Des délégations de militants communistes s’y pressent ; la réunion est secrètement supervisée par le Kominform. Mais l’hôtel est sous contrôle de la CIA, qui y a installé un quartier général secret au dixième étage. Sidney Hook, qui joue le communiste repenti, reçoit à part des journalistes auxquels il explique « sa » stratégie contre « les staliniens » : intercepter le courrier du Waldorf et diffuser de faux communiqués. Profitant de la « position de cheval de Troie » de Sidney Hook, la CIA mène une campagne d’intoxication médiatique allant jusqu’à divulguer publiquement l’appartenance politique de certains participants préfigurant ainsi la « chasse aux sorcière » du sénateur McCarthy. Avec zèle et brio, Hook mène son équipe d’agitateurs, de délateurs et de manipulateurs, rédigeant des tracts et semant le désordre lors des tables rondes… Simultanément, à l’extérieur de l’hôtel Waldorf, des dizaines de militants d’extrême-droite défilent pancarte à la main pour dénoncer l’ingérence du Kominform. L’opération est un succès total, la conférence tourne au fiasco. ?Tirant les leçons du « coup du Waldorf », la CIA états-unienne et l’IRD britannique systématisent l’enrôlement de trotskistes dans la lutte secrète contre Moscou, au point d’en faire une constante de la « guerre psychologique » qu’ils livrent à l’URSS.

Sidney Hook, chef de file des New York Intellectuals

Né dans un quartier pauvre de Brooklyn en 1902, Sidney Hook entre en 1923 à l’université de Colombia où il rencontre John Dewey, son premier maître à penser. Après son doctorat, il obtient une bourse de la fondation Guggenheim qui lui permet d’étudier en Allemagne et de visiter Moscou. Comme tant d’autres intellectuels de l’époque, il est fasciné par Staline et le régime soviétique. À son retour aux États-Unis, il débute sa carrière à l’université de New York au département de Philosophie. Il ne quittera son poste qu’en 1972 pour s’installer à Stanford au terme d’une évolution intellectuelle qui l’aura conduit du communisme au néoconservatisme. À la fin de la Première Guerre mondiale, après s’être marié avec une militante communiste, Hook s’inscrit dans un syndicat d’enseignants proche du Parti. Il travaille à une traduction de Lénine et publie un livre remarqué, Towards the understanding of Karl Marx. Intellectuel typique de la gauche radicale, il participe aux manifestations contre l’exécution des anarchistes Sacco et Vanzetti.

Au début des années 30, Hook rompt avec les communistes et se rallie au clan des trotskistes réunis au sein de l’American Workers Party, fondé en 1938. Il organise la « Commission d’enquête sur la vérité dans les procès de Moscou » qui a pour but d’innocenter Trotski écarté du pouvoir par Staline.

À partir de 1938, il abandonne définitivement l’idéal révolutionnaire. En 1939, il fonde le Committee for cultural freedom, une organisation antistalinienne qui constituera, après la guerre, l’une des bases du Congress for cultural freedom. Plus qu’une rupture, cette « trahison » – Hook surveille ses anciens amis pour le compte de la CIA – constitue pour lui une opportunité politique et financière attractive. Lorsque Hook évoque les raisons de sa conversion, il désigne des « staliniens » comme Brecht qui, au cours d’une discussion à New York en 1935 aurait plaisanté à propos de l’arrestation de Zinoviev et Kamenev : « Ceux-là, plus ils sont innocents, plus ils méritent d’être fusillés ». Une dénonciation qui en dit long sur les méthodes de Hook qui n’hésitait pas à citer des propos critiques en les retirant de leur contexte pour les rendre odieux.

Dans cette logique de délation, l’initiative du sénateur du Wisconsin, McCarthy, est soutenue discrètement par Hook qui publie deux articles, « Heresy, yes ! Conspiracy, no ! » (Hérésie, oui ! Conspiration, non !) et « The dangers of cultural vigilantism » (Les dangers de la vigilance culturelle) dans lesquels, prétendant critiquer McCarthy, il encourage à espionner et dénoncer les fonctionnaires, intellectuels et politiques proches des communistes. Hook a toujours prétendu par la suite qu’il n’avait jamais soutenu le sénateur du Wisconsin, ce que récuse la philosophe Hannah Arendt, pourtant alliée naturelle de Hook. Dans « Heresy, yes ! », il décrit la postures idéologique des « libéraux réalistes » et la notion de « culpabilité par fréquentation ». Il en déduit que l’État doit mener la « chasse aux sorcières » en gardant l’apparence d’un régime libéral. Pour cela, l’administration, plutôt que de criminaliser les fonctionnaires communistes, doit pouvoir amener les individus suspects à démissionner. Concernant les enseignants, Hook note qu’un professeur communiste « pratique une véritable fraude professionnelle ». Au finale, Hook considère que la « chasse aux sorcières » constitue une erreur politique, non pas en raison de la nature fasciste de cette campagne de délation, mais plutôt parce que l’initiative de McCarthy, trop peu discrète, contribue à mettre en équivalence la violence soviétique et états-unienne. Dans « The dangers of vigilantism », il préconise d’autres moyens, plus secrets, afin de chasser les communistes : il s’agit par exemple de confier la charge des enquêtes de loyauté aux instances professionnelles.

Effectivement Sidney Hook préfère les actions discrètes. Son implication dans plusieurs opérations de la Guerre froide culturelle, dont le Congrès pour la liberté de la culture, met en évidence sa conception de la démocratie, conçue comme une façade nécessaire du bloc atlantiste mené par les États-Unis. En 1972, il quitte New York et devient jusqu’à sa mort l’un des principaux théoriciens conservateurs rassemblés au sein de la Hoover Institution. En fréquentant les cercles de la diplomatie secrète, Sidney Hook devient un conservateur respecté par les gouvernants. En 1985, Ronald Reagan lui remet la plus haute distinction civile états-unienne, la Medal of Freedom après avoir décoré, le même jour Frank Sinatra et Jimmy Stewart. Il meurt en 1989. Sa femme reçoit les condoléances du Président Bush : « Pendant toute sa vie, il fut un défenseur sans peur de la Liberté (…) Alors qu’il affirmait souvent qu’il n’existe rien d’absolu dans la vie, l’ironie voulut qu’il prouve lui-même le contraire car s’il y eut un absolu, ce fut Sidney Hook toujours prêt à combattre courageusement pour l’honnêteté intellectuelle et la vérité ».

Convertir les trotskistes

La « trahison » de Sidney Hook qui a rendu possible la réussite de la campagne d’intoxication du Waldorf est le point de départ d’un mouvement de conversion d’une fraction de l’aile trotsksite. La CIA et l’IRD font confiance aux marxistes repentis pour mener à bien une opération de grande envergure : la fabrication d’une « idéologie rivalisant avec le communisme », selon l’expression de Ralph Murray, premier chef de l’IRD, dont le Congrès pour la liberté de la culture sera le principal instrument de promotion.

La tactique de la CIA et l’IRD consiste donc, dans un premier temps, à « retourner » des militants trotskistes et à s’assurer de leur obéissance. Pour cela, les services investissent une partie des fonds secrets dont ils disposent afin de « sauver » des revues radicales de la faillite totale. Ainsi la Partisan Review, fief des New York Intellectuals, ancienne tribune communiste orthodoxe, puis trotskiste, reçoit plusieurs dons. En 1952, le chef de l’Empire Time-Life, Henry Luce, verse grâce à Daniel Bell 10 000 dollars pour que la revue ne disparaisse pas. La même année, Partisan Review organise un symposium dont le thème général peut être résumé ainsi : « l’Amérique est maintenant devenue la protectrice de la civilisation occidentale ». Dès 1953, alors que les New York Intellectuals dominent le Congrès pour la liberté de la culture, Partisan Review reçoit une subvention issue du « compte du festival » du Comité américain pour la liberté de la culture, alimenté par la fondation Farfield… avec des fonds de la CIA. De la même manière, New leader animé par Sol Levitas est « sauvé » après l’intervention financière de Thomas Braden… avec l’argent de la CIA. On comprend mieux comment l’agence est parvenue à fidéliser certains groupes de la gauche radicale.

La tactique de la CIA et l’IRD consiste donc, dans un premier temps, à « retourner » des militants trotskistes et à s’assurer de leur obéissance. Pour cela, les services investissent une partie des fonds secrets dont ils disposent afin de « sauver » des revues radicales de la faillite totale. Ainsi la Partisan Review, fief des New York Intellectuals, ancienne tribune communiste orthodoxe, puis trotskiste, reçoit plusieurs dons. En 1952, le chef de l’Empire Time-Life, Henry Luce, verse grâce à Daniel Bell 10 000 dollars pour que la revue ne disparaisse pas. La même année, Partisan Review organise un symposium dont le thème général peut être résumé ainsi : « l’Amérique est maintenant devenue la protectrice de la civilisation occidentale ». Dès 1953, alors que les New York Intellectuals dominent le Congrès pour la liberté de la culture, Partisan Review reçoit une subvention issue du « compte du festival » du Comité américain pour la liberté de la culture, alimenté par la fondation Farfield… avec des fonds de la CIA. De la même manière, New leader animé par Sol Levitas est « sauvé » après l’intervention financière de Thomas Braden… avec l’argent de la CIA. On comprend mieux comment l’agence est parvenue à fidéliser certains groupes de la gauche radicale.

En plus du « sauvetage » de Partisan Review, la CIA collabore avec les services britanniques afin de créer une revue anticommuniste. Il recrute ainsi Irving Kristol, le directeur exécutif du Comité américain pour la liberté de la culture. Kristol est entré en 1936 à City College où il rencontre deux futurs camarades de la guerre froide, Daniel Bell et Melvin Lasky. Trotskiste antistalinien, il travaille pour la revue Enquiry. Après la guerre, recruté par les services états-uniens il retourne à New York pour diriger la revue juive Commentary. Directement financé par les crédits Farfield (CIA), il est chargé d’inventer Encounter sous la surveillance de Josselson. Le « magazine X », qu’il dirige avec le naïf Stephen Spender sera le fer de lance de l’idéologie néoconservatrice états-unienne.

La lutte contre le communisme au Congrès pour la liberté de la culture

Les New York Intellectuals et autres communistes repentis sont logiquement contactés par Josselson (placé sous les ordres de Lawrence de Neufville) qui, pour le compte de la CIA, est chargé de créer le Congrès pour la liberté de la culture. L’objectif est alors d’organiser en Europe de l’Ouest la « guerre psychologique », selon l’expression d’Arthur Koestler, contre Moscou.

Arthur Koestler, né en 1905 à Budapest, a été un militant communiste actif pendant plusieurs années. En 1932, il visite l’Union soviétique. L’Internationale finance l’un de ses livres. Après avoir dénoncé à la police secrète sa petite amie russe, il quitte Moscou et rejoint Paris. Pendant la guerre, il est arrêté et déporté en tant que prisonnier politique. La guerre terminée, Koestler écrit Le Zéro et l’infini, un livre dans lequel il retrace son parcours et dénonce les crimes du stalinisme. La rencontre des New York Intellectuals, par l’intermédiaire de James Burnham, lui permet de fréquenter les milieux où se décident les opérations culturelles secrètes. À la suite de nombreux entretiens avec des agents de la CIA, il supervise l’écriture d’un ouvrage collectif, une commande directe des services. Le Dieu des ténèbres (André Gide, Stephen Spender…) constitue une sévère condamnation du régime soviétique. Arthur Koestler est ensuite employé dans le cadre de la mise en place du Congrès pour la liberté de la culture.

Koestler écrit le Manifeste des hommes libres à la suite de la réunion du Kongress für Kulturelle freiheit de Berlin organisé en 1950 par son ami Melvin Lasky. Pour lui, « la liberté a pris l’offensive ». James Burnham est largement responsable du recrutement de Koestler qui va vite devenir, en raison de son enthousiasme, trop gênant aux yeux des conspirateurs du Congrès.

Le parrain de Koestler, James Burnham, est né en 1905 à Chicago. Professeur à l’université de New York, il collabore à diverses revues radicales et participe à la construction du Socialist Workers Party. Quelques années plus tard, il organisera la scission du groupe trotskiste. En 1941, il publie The Managerial Revolution, futur manifeste du Congrès pour la liberté de la culture, traduit en France en 1947 sous le titre de L’Ère des organisateurs. La conversion de Burnham est particulièrement spectaculaire. En quelques années, après avoir rencontré le chef des réseaux stay-behind, Franck Wisner et son assistant Carmel Offie, il devient un ardent défenseur des États-Unis, selon lui unique rempart face à la barbarie communiste. Il déclare : « Je suis contre les bombes actuellement entreposées en Sibérie ou au Caucase et qui sont destinées à la destruction de Paris, Londres, Rome, (…) et de la civilisation occidentale en général (…) mais je suis pour les bombes entreposées à Los Alamos (…) et qui depuis cinq ans sont la défense – l’unique défense – des libertés de l’Europe occidentale ». Parfaitement conscient de la fonction du réseau stay-behind, Burnham, ami intime de Raymond Aron, passe du trotskisme à la droite conservatrice devenant l’un des intermédiaire principaux entre les intellectuels du Congrès et la CIA. En 1950, lorsque le turbulent Melvin Lasky reçoit des fonds détournés du Plan Marshall, Burnham, Hook et Koestler sont vraisemblablement mis dans la confidence. Burnham va pouvoir, grâce au Congrès pour la liberté de la culture diffuser dans toute l’Europe de l’Ouest son livre The Managerial Revolution.

« Une idéologie rivalisant avec le communisme »

Raymond Aron est le principal artisan de l’importation en France des thèses des New York Intellectuals. En 1947, il sollicite les éditions Calmann-Lévy afin de afin de faire publier la traduction de The Managerial Revolution. Au même moment, Burnham défend aux États-Unis son nouveau livre Struggle for the World (Pour une domination mondiale). L’Ère des organisateurs est immédiatement interprété (à juste titre), notamment par le professeur Georges Gurvitch, comme une apologie de la « technocratie ».

Cherchant à disqualifier l’analyse en termes de luttes de classe, Burnham déclare que les directeurs sont les nouveaux maîtres de l’économie mondiale. Selon l’auteur, l’Union soviétique, loin d’avoir réalisé le socialisme, est un régime dominé par une nouvelle classe constituée de « techniciens » (dictature bureaucratique). En Europe de l’Ouest et aux États-Unis, les directeurs ont pris le pouvoir au détriment des parlements et du patronat traditionnel. Ainsi, l’ère directoriale signifie un double échec, celui du communisme et du capitalisme. La principale cible de Burnham est évidemment l’analyse marxiste-léniniste dont le principe, la dialectique historique, annonce l’avènement d’une société communiste mondiale. En fait, « le socialisme ne succédera pas au capitalisme » ; les moyens de production, partiellement étatisés, seront confiés à une classe de directeurs, seul groupe capable de diriger, en raison de leur compétence technique, l’État contemporain.

Léon Blum a bien compris la dimension fondamentalement anti-marxiste des thèses technocratiques de James Burnham. Après la guerre, en tant qu’allié de Washington, l’ancien homme fort du Front populaire doit pourtant préfacer la traduction française, non sans une certaine gêne : « Si je n’étais sûr de la sympathie des uns et de l’amitié des autres, j’aurais vu dans cette demande comme une trace de malice (…) on imagine guère d’ouvrage qui, sur la pensée d’un lecteur socialiste, puisse exercer un choc plus inattendu et plus troublant ». Avec un parrain comme Raymond Aron et un préfacier comme Léon Blum, L’Ère des organisateurs connaît un succès considérable.

Proche de Sidney Hook avec qui il soutient la « chasse aux sorcières », Daniel Bell publie en 1960 La Fin des idéologies, un recueil d’articles publiés dans Commentary, Partisan Review, New Leader et de communications du Congrès pour la liberté de la culture. La traduction française est préfacée par Raymond Boudon, qui durant toute sa vie a combattu les théories de l’école française de sociologie incarnée par Émile Durkheim et Pierre Bourdieu dans le but d’imposer une conception américanisée des sciences sociales. La Fin des idéologies, comme son nom l’indique, reprend la thèse favorite des New York Intellectuals, à savoir l’extinction du communisme comme idéal. Daniel Bell, membre actif du Congrès pour la liberté de la culture qui contribue à diffuser son livre, annonce aussi l’émergence de nouveaux conflits idéologiques : « La Fin des idéologies fait le pronostic de la désintégration du marxisme comme foi, mais ne dit pas que toute idéologie va vers sa fin. J’y remarque plutôt que les intellectuels sont souvent avides d’idéologies et que de nouveaux mouvements sociaux ne manqueront pas d’en engendrer de nouvelles, qu’il s’agisse du panarabisme, de l’affirmation d’une couleur ou du nationalisme »

De l’anticommunisme au néo-conservatisme

Les New York Intellectuals, engagés dans de multiples opérations d’infiltration, ne revèlent leur véritable appartenance idéologique que tardivement rejoignant massivement les rangs des néoconservateurs dont les principaux bastions sont déjà tenus par des marxistes repentis. Irving Kristol, qui entretient des rapports conflictuels avec Josselson, dirige de 1947 à 1952 Commentary. Une autre figure majeure du néoconservatisme, Norman Podhoretz, sera ensuite placée à la tête de la revue quasi-officielle du Congrès pour la liberté de la culture de 1960 à 1995. En France, Raymond Aron crée Commentaire en 1978. Le fils d’Irving Kristol, William, est le directeur du très néoconservateur Weekly Standard.

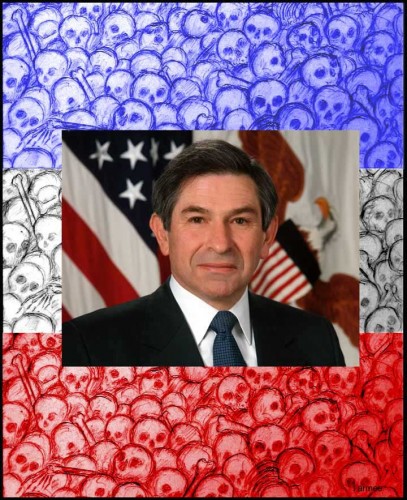

William Kristol

Contrairement à une thése répandue, il n’y a pas eu d’infiltration trotskiste dans la droite états-unienne, mais une récupération par celle-ci d’éléments trotskistes, d’abord dans une alliance objective contre le stalinisme, puis pour employer leurs capacités dialectiques au service de l’impérialisme pseudo-libéral. Burnham et Shatchman quittent le Socialist Workers Party et la IVe Internationale en 1940 pour fonder un parti scisionniste. Max Shatchman prône bientôt l’entrisme dans le Parti démocrate. Il rejoint le faucon démocrate Henry « Scoop » Jackson, surnommé le « sénateur Boeing » en raison de son soutien acharné au complexe militaro-industriel. Il réorganise son parti comme une tendance au sein du Parti démocrate sous l’appellation Parti des sociaux démocrates états-uniens (SD/USA). Au cours des années 70, le sénateur Jackson s’entoure de brillants assistants tels que Paul Wolfowitz, Doug Feith, Richard Perle, Elliot Abrams. En conservant le plus longtemps possible son discours d’extrême gauche, Max Shatchman fait de SD/USA une officine de la CIA apte à discréditer les formations d’extrême gauche, tandis qu’il devient l’un des principaux conseillers de l’organisation syndicale anticommuniste AFL-CIO. On trouve au bureau politique de SD/USA des personnalités comme Jeanne Kirkpatrick qui deviendront des icônes de l’ère Reagan. Dans une complète confusion des genres, le théoricien d’extrême droite Paul Wolfowitz intervient comme orateur aux congrès du parti d’extrême gauche. Carl Gershamn devient président de SD/USA, il est aujourd’hui directeur exécutif de la National Endowment for Democracy. D’une manière générale les membres de ce parti, dont les principaux relais sont la revue Commentary et le Committee for the Free World, sont récompensés pour leurs manipulations dès l’élection de Ronald Reagan.

Les New York Intellectuals n’ont pas seulement développé une critique de gauche du communisme, ils ont aussi inventé un habillage « de gauche » aux idées d’extrême droite dont la maturation finale est le néoconservatisme. Ainsi, les Kristol et leurs amis peuvent-ils présenter avec aplomb George W. Bush comme un « idéaliste » qui s’emploie à « démocratiser » le monde.

- Source : Denis Boneau

00:05 Publié dans Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : trotskisme, néo-conservatisme, états-unis, théorie politique, philosophie, philosophie politique, politologie, histoire, sciences politiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 04 mai 2013

Le trotskisme dégénéré

Le trotskisme dégénéré

« Il est indispensable de démonter pièce par pièce le véhicule funèbre du trotskisme. Il faut dresser son bilan historique,falsifié par lui-même avec le même cynisme crapuleux que le stalinisme, son frère ennemi »

Entretien avec Patrick Gofman, auteur du livre Le Trotskisme dégénéré (éditions Les Bouquins de Synthèse nationale)

Entretien avec Patrick Gofman, auteur du livre Le Trotskisme dégénéré (éditions Les Bouquins de Synthèse nationale)

(propos recueillis par Fabrice Dutilleul).

Naufrage avec son concurrent stalinien

Pourquoi la chaloupe trotskiste coule-t-elle avec le Titanic stalinien ?

Parce qu’elle est à sa remorque ! Depuis 1938, le trotskisme, dans ses mille et une chapelles, se présente comme la direction alternative du prolétariat révolutionnaire mondial. La disparition du pouvoir soviétique, l’effondrement électoral et moral du PCF devrait donc ouvrir un boulevard aux trotskistes ? Eh bien, non. Les remous de l’immense naufrage stalinien entraînent vers le fond les frêles esquifs de son opposition de gauche. Patrick Gofman décrit ici avec précision, brièveté, références, humour et cruauté, les dégénérescences parallèles des staliniens et des stalinains, leur choc fatal avec l’iceberg de l’Histoire, leurs derniers gargouillis dans l’eau glaciale.

Eh bien, Monsieur Gofman, vous tirez sur les ambulances, à présent ?

Les corbillards, vous voulez dire ? Oui, c’est bien triste. Mais il est indispensable de démonter pièce par pièce le véhicule funèbre du trotskisme. Il faut dresser son bilan historique, falsifié par lui-même avec le même cynisme crapuleux que le stalinisme, son frère ennemi.

Mais quelle importance ?!

Le stalinisme et son appendice trotskiste se sont emparés d’un mythe – utopie ou uchronie, si vous préférez – permanent et fondamental de l’humanité : le communisme. « Partageons tout en frères ». Ils ont souillé, défiguré, empoisonné ce beau rêve. Il ne faut pas permettre que l’ultra-libéralisme mondialiste l’enterre pour mille ans avec ses falsificateurs.

De quoi vous mêlez-vous ?

De mes oignons. J’ai donné ma jeunesse (1967-79) au trotskisme, dans sa variante « lambertiste », la plus sectaire et dogmatique. Mon expérience et ma documentation m’autorisent à montrer la dégénérescence et la nature criminelle du bolchevisme intégriste. Du moins, je veux ouvrir la voie à des historiens plus compétents, tout comme mon roman Cœur-de-Cuir (Flammarion, 1998) a été suivi d’autres révélations.

Le trotskisme dégénéré de Patrick Gofman, 134 pages, 18 euros, éditions Les Bouquins de Synthèse nationale, dirigée par Roland Hélie. Cliquez ici ou cliquez là

00:05 Publié dans Entretiens | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : trotskisme, idéologie, patrick gofman |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 14 février 2013

De trotskistische wortels van het neoconservatisme

Filip MARTENS:

De trotskistische wortels van het neoconservatisme

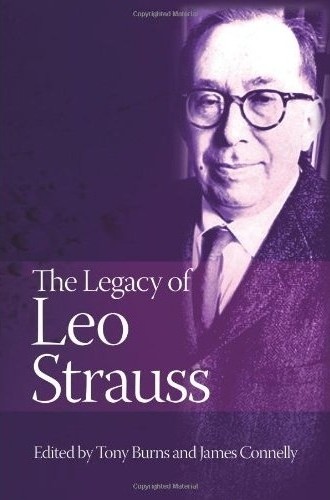

De neoconservatieve ideologie kreeg vanaf het begin der jaren 1980 een toenemende invloed in de internationale politiek. Ondanks de misleidende naam is het neoconservatisme echter helemaal niet conservatief, maar wel een linkse ideologie die het Amerikaanse conservatisme kaapte. Hoewel het neoconservatisme niet tot één bepaalde denker te herleiden valt, worden de politieke filosoof Leo Strauss (1899-1973) en de socioloog Irving Kristol (1920-2009) algemeen als grondleggers beschouwd.

1. De stichters van het neoconservatisme

Leo Strauss werd in een joods gezin in de Duitse provincie Nassau geboren. Hij was een actieve zionist tijdens zijn studentenjaren in het Duitsland van na de Eerste Wereldoorlog. In 1934 emigreerde Strauss naar Groot-Brittannië en in 1937 naar de VS, waar hij aanvankelijk aangesteld werd aan de Colombia University in New York. In 1938-1948 was hij hoogleraar politieke filosofie aan de New School for Social Research in New York en in 1949-1968 aan de University of Chicago.

Aan de University of Chicago leerde Strauss zijn studenten dat het Amerikaanse secularisme zijn eigen vernietiging inhield: het individualisme, egoïsme en materialisme ondermijnden immers alle waarden en moraal en leidden in de jaren 1960 tot enorme chaos en rellen in de VS. De creatie en cultivering van religieuze en vaderlandslievende mythes zag hij als oplossing. Strauss stelde dat leugens om bestwil geoorloofd zijn om de maatschappij samen te houden en te sturen. Bijgevolg waren volgens hem door politici geponeerde en niet te bewijzen mythes noodzakelijk om de massa een doel te geven, wat tot een stabiele maatschappij zou leiden. Staatslieden moesten dus sterke inspirerende mythes creëren, die niet noodzakelijk met de waarheid moesten overeenstemmen. Strauss was hiermee één der inspirators achter het neoconservatisme dat in de jaren 1970 opkwam in de Amerikaanse politiek, hoewel hij zelf nooit aan actieve politiek deed en altijd een academicus bleef.

Aan de University of Chicago leerde Strauss zijn studenten dat het Amerikaanse secularisme zijn eigen vernietiging inhield: het individualisme, egoïsme en materialisme ondermijnden immers alle waarden en moraal en leidden in de jaren 1960 tot enorme chaos en rellen in de VS. De creatie en cultivering van religieuze en vaderlandslievende mythes zag hij als oplossing. Strauss stelde dat leugens om bestwil geoorloofd zijn om de maatschappij samen te houden en te sturen. Bijgevolg waren volgens hem door politici geponeerde en niet te bewijzen mythes noodzakelijk om de massa een doel te geven, wat tot een stabiele maatschappij zou leiden. Staatslieden moesten dus sterke inspirerende mythes creëren, die niet noodzakelijk met de waarheid moesten overeenstemmen. Strauss was hiermee één der inspirators achter het neoconservatisme dat in de jaren 1970 opkwam in de Amerikaanse politiek, hoewel hij zelf nooit aan actieve politiek deed en altijd een academicus bleef.

Irving Kristol was de zoon van Oost-Europese joden die in de jaren 1890 emigreerden naar Brooklyn, New York. In de eerste helft der jaren 1940 was hij lid van de Vierde Internationale van Leon Trotski (1879-1940), de door Stalin uit de USSR verbannen bolsjewistische leider die met deze rivaliserende communistische beweging Stalin bestreed. Vele vooraanstaande Amerikaans-joodse intellectuelen traden toe tot de Vierde Internationale.

Kristol was tevens lid van de invloedrijke New York Intellectuals, een eveneens anti-stalinistisch en anti-USSR collectief van trotskistische joodse schrijvers en literaire critici uit New York. Naast Kristol behoorden hier ook Hannah Arendt, Daniel Bell, Saul Bellow, Marshall Berman, Nathan Glazer, Clement Greenberg, Richard Hofstadter, Sidney Hook, Irving Howe, Alfred Kazin, Mary McCarthy, Dwight MacDonald, William Phillips, Norman Podhoretz, Philip Rahy, Harold Rosenberg, Isaac Rosenfeld, Delmore Schwartz, Susan Sontag, Harvey Swados, Diana Trilling, Lionel Trilling, Michael Walzer, Albert Wohlstetter en Robert Warshow toe. Velen van hen hadden gestudeerd aan het City College of New York, de New York University en de Colombia University in de jaren 1930 en 1940. Ze woonden tevens voornamelijk in de New Yorkse stadsdelen Brooklyn en de Bronx. Tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog groeide bij deze trotskisten het besef dat de VS nuttig kon zijn om de door hen gehate USSR te bestrijden. Sommigen van hen, zoals Glazer, Hook, Kristol en Podhoretz, ontwikkelden later het neoconservatisme, dat het trotskistische universalisme en zionisme behield.

Kristol begon als een overtuigd marxist bij de Democratische Partij. Hij was in de jaren 1960 een leerling van Strauss. Hun neoconservatisme bleef geloven in de marxistische maakbaarheid van de wereld: de VS moest internationaal actief optreden om de parlementaire democratie en het kapitalisme te verspreiden. Daarom was Kristol een fel voorstander van de Amerikaanse oorlog in Vietnam. Strauss en Kristol verwierpen bovendien de liberale scheiding van Kerk en Staat, daar de seculiere maatschappij tot individualisme leidde. Zij maakten religie weer bruikbaar voor de Staat.

Kristol verspreidde zijn gedachtegoed als hoogleraar sociologie aan de New York University, via een column in de Wall Street Journal, via de door hem gestichte tijdschriften The Public Interest en The National Interest en via het door zijn zoon William Kristol gestichte invloedrijke neocon-weekblad The Weekly Standard (dat gefinancierd wordt door mediamagnaat Rupert Murdoch).

Kristol was tevens betrokken bij het in 1950 door de CIA opgerichte en gefinancierde Congress for Cultural Freedom. Deze in ca. 35 landen actieve anti-USSR organisatie gaf het Britse blad Encounter uit, dat Kristol samen met de Britse ex-marxistische dichter en schrijver Stephen Spender (1909-1995) oprichtte. Spender voelde zich door zijn gedeeltelijke joodse afkomst erg aangetrokken tot het jodendom en was ook gehuwd met de joodse concertpianiste Natasha Litvin. Toen in 1967 de betrokkenheid van de CIA bij het Congress for Cultural Freedom uitlekte in de pers, trok Kristol zich er uit terug en engageerde zich in de neocon-denktank American Enterprise Institute.

Kristol redigeerde tevens samen met Norman Podhoretz (°1930) het maandblad Commentary in 1947-1952. Podhoretz was de zoon van joodse marxisten uit Galicië, die zich in Brooklyn vestigden. Hij studeerde aan de Columbia University, het Jewish Theological Seminary en de University of Cambridge. In 1960-1995 was Podhoretz hoofdredacteur van Commentary. Zijn invloedrijke essay ‘My Negro Problem – And Ours’ uit 1963 bepleitte een volledige raciale vermenging van het blanke en zwarte ras daar voor hem “the wholesale merging of the 2 races the most desirable alternative” was.

Podhoretz was in 1981-1987 adviseur van de US Information Agency, een Amerikaanse propagandadienst die tot doel had om buitenlandse publieke opinies en staatsinstellingen op te volgen en te beïnvloeden. In 2007 kreeg Podhoretz de Guardian of Zion Award, een jaarlijkse prijs die de Israëlische Bar-Ilan Universiteit schenkt aan een belangrijke steunpilaar van de staat Israël.

Andere leidende namen in deze nieuwe ideologie waren Allan Bloom, Podhoretz’ vrouw Midge Decter en Kristols vrouw Gertrude Himmelfarb. Bloom (1930-1992) werd geboren in een joods gezin in Indiana. Aan de University of Chicago werd hij sterk beïnvloed door Leo Strauss. Later werd Bloom hoogleraar filosofie aan diverse universiteiten. De latere hoogleraar Francis Fukuyama (°1952) was een van zijn studenten. De joodse feministische journaliste en schrijfster Midge Decter (°1927) was een der stichters van de neocon-denktank Project for the New American Century en zetelt tevens in de raad van bestuur van de neocon-denktank Heritage Foundation. De joodse historica Gertrude Himmelfarb werd in 1922 geboren in Brooklyn. Tijdens haar studies aan de University of Chicago, het Jewish Theological Seminary en de University of Cambridge was ze een actieve trotskiste. Later was Himmelfarb actief in de neocon-denktank American Enterprise Institute.

2. De trotskistische wortels van het neoconservatisme

Het neoconservatisme wordt onterecht als ‘rechts’ beschouwd vanwege het voorvoegsel ‘neo’, dat verkeerdelijk een nieuw conservatief denken suggereert. Vele neocons hebben echter integendeel een extreem-links verleden, namelijk in het trotskisme. De meeste neocons stammen immers af van trotskistische joodse intellectuelen uit Oost-Europa (voornamelijk Polen, Litouwen en Oekraïne). Daar de USSR in de jaren 1920 het trotskisme verbande, is het begrijpelijk dat zij in de VS actief werden als anti-USSR lobby binnen de links-liberale Democratische Partij en in andere linkse organisaties.

Irving Kristol definieerde een neocon als “een progressief die getroffen werd door de realiteit”. Dit wijst er op dat een neocon iemand is die wisselde van politieke strategie om zo beter zijn doelen te kunnen bereiken. In de jaren 1970 ruilden de neocons immers het trotskisme in voor het liberalisme en verlieten de Democratische Partij. Vanwege hun sterke aversie tegen de USSR en tegen de verzorgingsstaat sloten zij om strategische redenen aan bij het anticommunisme der Republikeinen.

Als voormalige trotskist bleef de neocon Kristol marxistische ideeën promoten, zoals reformistisch socialisme en internationale revolutie via natievorming en militair opgelegde democratische regimes. Daarnaast verdedigen de neocons progressieve eisen als abortus, euthanasie, massa-immigratie, mondialisering, multiculturalisme en vrijhandelskapitalisme. Ook de verzorgingsstaten worden gezien als overbodig, hoewel de bevolking liefst haar moeizaam opgebouwde sociale zekerheid ziet blijven bestaan. De neocons zwaaien daarom met zwaar overdreven doemscenario’s – zoals vergrijzing en mondialisering – om de bevolking rijp te maken voor een slachtpartij in de overheidssector en in de sociale voorzieningen. Ze zoeken daarvoor steun bij de liberaal-kapitalistische politieke krachten. Ook de term ‘armoedeval’ (poverty trap), die slaat op werklozen die niet gaan werken omdat de daardoor veroorzaakte kosten hun iets hogere inkomen uit arbeid afzwakken, werd uitgevonden door neocons.

Stuk voor stuk zijn dit kernconcepten van de neocon-filosofie. In 1979 noemde het tijdschrift Esquire Irving Kristol “the godfather of the most powerful new political force in America: neoconservatism”. Dat jaar verscheen ook Peter Seinfels’ boek ‘The Neoconservatives: The Men Who Are Changing America’s Politics’, dat wees op de toenemende politieke en intellectuele invloed der neocons.

Het maandblad Commentary was de opvolger van het in 1944 stopgezette blad Contemporary Jewish Record en werd in 1945 gesticht door het American Jewish Committee. Onder hoofdredacteur Elliot Cohen (1899-1959) richtte Commentary zich op de traditioneel zeer linkse joodse gemeenschap, terwijl het tegelijk de ideeën van jonge joodse intellectuelen bij een breder publiek wou bekendmaken. Norman Podhoretz, die in 1960 hoofdredacteur werd, stelde dan ook terecht dat Commentary de radicaal-trotskistische joodse intellectuelen verzoende met het liberaal-kapitalistische Amerika. Commentary vaarde een anti-USSR koers en ondersteunde volop de 3 pilaren van de Koude Oorlog: de Truman-doctrine, het Marshallplan en de NAVO.

Dit tijdschrift over politiek, maatschappij, jodendom en sociaal-culturele onderwerpen speelt sinds de jaren 1970 een leidinggevende rol in het neoconservatisme. Commentary vormde het joodse trotskisme om tot het neoconservatisme en is het invloedrijkste Amerikaanse blad van de voorbije halve eeuw omdat het het Amerikaanse politieke en intellectuele leven grondig veranderde. Immers, het verzet tegen de Vietnamoorlog, tegen het aan die oorlog ten grondslag liggende kapitalisme en vooral de vijandigheid tegen Israël in de Zesdaagse Oorlog van 1967 wekten de woede van hoofdredacteur Podhoretz. Commentary schilderde deze oppositie daarom af als anti-amerikaans, antiliberaal en antisemitisch. Dit leidde tot het ontstaan van het neoconservatisme, dat hevig de liberale democratie verdedigde en zich afzette tegen de USSR en tegen Derde Wereldlanden die het neokolonialisme bestreden. Strauss’ studenten – onder meer Paul Wolfowitz (°1943) en Allan Bloom – stelden dat de VS een strijd tegen ‘het Kwade’ moest voeren en de als ‘Goed’ beschouwde parlementaire democratie en kapitalisme in de wereld verspreiden.

Daarnaast praatten zij de Amerikaanse bevolking een – fictief – islamgevaar aan, op basis waarvan ze Amerikaanse interventie in het Nabije Oosten voorstaan. Maar bovenal pleiten neocons voor enorme en onvoorwaardelijke steun van de VS aan Israël, zelfs in die mate dat de traditionele conservatief Russel Kirk (1918-1994) ooit stelde dat neocons de Amerikaanse hoofdstad verwarden met Tel-Aviv. Volgens Kirk was dit zelfs het hoofdonderscheid tussen neocons en de oorspronkelijke Amerikaanse conservatieven. Hij waarschuwde reeds in 1988 dat het neoconservatisme zeer gevaarlijk en oorlogszuchtig was. De door de VS gevoerde Golfoorlog van 1990-1991 gaf hem meteen gelijk.

Neocons streven nadrukkelijk naar macht om hun hervormingen te kunnen doordrukken in de verwachting dat de kwaliteit der samenleving daardoor zal verbeteren. Daarbij zijn ze zozeer overtuigd van hun eigen gelijk dat ze niet wachten tot er brede steun is voor hun ingrepen, ook niet bij ingrijpende hervormingen. Daardoor is neoconservatisme een marxistische maakbaarheidsutopie.

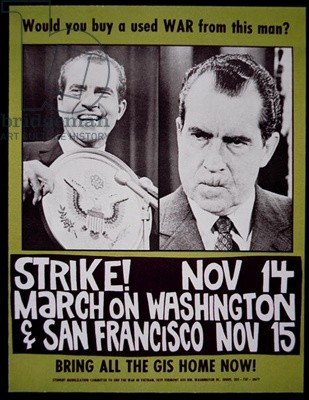

3. De neocons in het verzet tegen president Richard Nixon

In de jaren 1970 kwam het neoconservatisme op als verzetsbeweging tegen president Nixons beleid. De Republikein Richard Nixon (1913-1994) voerde samen met Henry Kissinger (°1923) – nationaal veiligheidsadviseur in 1969-1975 en minister van Buitenlandse Zaken in 1973-1977 – immers een volkomen ander buitenlands beleid door relaties aan te knopen met maoïstisch China en een détente te starten met de USSR. Daarnaast voerde Nixon ook een sociaal beleid en schafte hij de goudstandaard af, waardoor dollars niet langer inwisselbaar waren in goud.

Nixon en Kissinger maakten gebruik van de hoogoplopende spanningen en grensconflicten tussen de USSR en China om in 1971 in het diepste geheim relaties aan te knopen met China, waarna Nixon in februari 1972 als eerste Amerikaanse president maoïstisch China bezocht. Mao Zedong bleek enorm onder de indruk van Nixon. Uit vrees voor een Chinees-Amerikaanse alliantie zwichtte de USSR nu voor het Amerikaanse streven naar détente, waardoor Nixon en Kissinger de bipolaire wereld – het Westen vs. het communistische blok – omvormden in een multipolair machtsevenwicht. Nixon bezocht in mei 1972 Moskou en onderhandelde er met Sovjetleider Brezjnev handelsakkoorden en 2 baanbrekende wapenbeperkingsverdragen (SALT I en het ABM-verdrag). De vijandigheid van de Koude Oorlog werd nu vervangen door de détente, die de spanningen deed luwen. De relaties tussen USSR en VS verbeterden vanaf 1972 dan ook sterk. Eind mei 1972 kwam al een vijfjarig samenwerkings-programma inzake ruimtevaart tot stand. Dit leidde tot het Apollo-Sojoez-testproject in 1975, waarbij een Amerikaanse Apollo en een Sovjet-Sojoez een gezamenlijke ruimtevaartmissie uitvoerden.

China en de USSR bouwden nu hun steun af voor Noord-Vietnam, dat geadviseerd werd om vredesbesprekingen te starten met de VS. Hoewel Nixon aanvankelijk de oorlog in Zuid-Vietnam nog ernstig had doen escaleren door ook de buurlanden Laos, Cambodja en Noord-Vietnam aan te vallen, trok hij geleidelijk zijn troepen terug en kon Kissinger in 1973 een vredesakkoord sluiten. Nixon begreep immers dat voor een succesvolle vrede de USSR en China er bij betrokken moesten worden.

Nixon was voorts de overtuiging toegedaan dat een verstandig regeringsbeleid de gehele bevolking kon ten goede komen. Hij hevelde federale bevoegdheden over naar de deelstaten, zorgde voor meer voedselhulp en sociale hulp en stabiliseerde de lonen en prijzen. De defensieuitgaven daalden van 9,1% tot 5,8% van het BNP en het gemiddelde gezinsinkomen steeg. In 1972 werd de sociale zekerheid sterk uitgebreid door een minimuminkomen te garanderen. Nixon werd vanwege zijn succesvolle sociaal-economische beleid zeer populair. Hij werd dan ook in november 1972 herkozen met een van de allergrootste verkiezingsoverwinningen uit de Amerikaanse geschiedenis.

De neocons vormden toen nog binnen de Democratische Partij een oppositiebeweging, die hevig anti-USSR was en de détente van Nixon en Kissinger met de USSR afwees. Neocon-zakenlui stelden enorme geldsommen beschikbaar voor neocon-denktanks en -tijdschriften. In 1973 vroegen de Straussianen dat de VS druk zou uitoefenen op de USSR om Sovjetjoden te laten emigreren. Minister van Buitenlandse Zaken Kissinger – nochtans zelf een jood – vond echter dat de situatie der Sovjetjoden niets met Amerika’s belangen van doen had en weigerde dan ook de USSR hierop aan te spreken. De Democratische senator Henry Jackson (1912-1983) ondergroef de détente door het Jackson-Vanik-amendement van 1974, dat détente afhankelijk maakte van de bereidheid der USSR om Sovjetjoden te laten emigreren. Jackson werd in de Democratische Partij bekritiseerd vanwege zijn nauwe banden met de wapenindustrie en zijn steun voor de Vietnamoorlog en voor Israël. Voor dit laatste kreeg hij tevens aanzienlijke financiële steun van Amerikaanse joden. Diverse medewerkers van Jackson, zoals Elliot Abrams, Richard Perle (°1941), Benjamin Wattenberg (°1933) en Wolfowitz, zouden later leidinggevende neocons worden.

Kissinger was ook niet opgezet met de aanhoudende Israëlische verzoeken voor Amerikaanse steun en noemde de Israëlische regering “a sick bunch”: “We have vetoed 8 resolutions for the past years, given them 4 billion dollar in aid (…) and we still are treated as if we have done nothing for them”. Uit diverse bandopnames van het Witte Huis uit 1971 blijkt dat ook president Nixon ernstige twijfels had over de Israëllobby in Washington en over Israël.

Kissinger weerhield er Israël tijdens de Yom Kippoeroorlog van 1973 van om het omsingelde Egyptische 3de Leger in de Sinaï te vernietigen. Toen ook de USSR zijn pro-Arabische retoriek niet durfde hardmaken, kon hij Egypte uit het Sovjetkamp losweken en omvormen tot een bondgenoot der VS, wat een ernstige verzwakking van de Sovjetinvloed in het Nabije Oosten betekende.

Nixon zette ondertussen zijn sociale hervormingen voort. Zo voerde hij in februari 1974 een ziekteverzekering in op basis van werkgevers- en werknemersbijdragen. Hij diende echter in augustus 1974 af te treden vanwege het Watergate-schandaal, dat begon in juni 1972 en bestond uit een meer dan 2 jaar aanhoudende reeks sensationele media-‘onthullingen’ die diverse Republikeinse regeringsfunctionarissen en uiteindelijk president Nixon zelf in zeer ernstige moeilijkheden brachten.

In het bijzonder de krant Washington Post bevuilde het blazoen van de regering-Nixon aanzienlijk: de redacteuren Howard Simons (1929-1989) en Harry Rosenfeld (°1929) organiseerden al in een heel vroeg stadium de buitengewone berichtgeving over wat het Watergate-schandaal zou worden en zetten de journalisten Bob Woodward (°1943) en Carl Bernstein (°1944) op de zaak. Onder het goedkeurend oog van hoofdredacteur Benjamin Bradlee (°1921) suggereerden Woodward en Bernstein op basis van anonieme bronnen talloze verdachtmakingen tegen de regering-Nixon. Rosenfeld kwam uit een familie van Duitse joden die zich in 1939 in de Bronx, New York vestigden. Bernsteins joodse ouders waren lid van de Communist Party of America en werden gedurende 30 jaar geschaduwd door het FBI wegens subversieve activiteiten, waardoor zij een FBI-dossier van meer dan 2.500 bladzijden hadden. Woodward wordt al decennia beschuldigd van overdrijvingen en verzinsels in zijn verslaggeving, vooral inzake zijn anonieme bronnen over het Watergate-schandaal.

Door dit media-offensief tegen de regering-Nixon werd een intensief gerechtelijk onderzoek gevoerd en richtte de Senaat zelfs een onderzoekscommissie op die overheidsmedewerkers begon te dagvaarden. Nixon diende bijgevolg in 1973 diverse topmedewerkers te ontslaan en kwam uiteindelijk zelf onder vuur te liggen, hoewel hij niets te maken had met de inbraak en de smeergeldaffaire die aan de basis van het Watergate-schandaal lagen. Vanaf april 1974 werd openlijk gespeculeerd over de afzetting van Nixon en toen dit in de zomer van 1974 effectief dreigde te gebeuren, nam hij op 9 augustus zelf ontslag. Minister van Buitenlandse Zaken Kissinger voorspelde tijdens deze laatste dagen dat de geschiedschrijving Nixon zou herinneren als een groot president en dat het Watergate-schandaal slechts een voetnoot zou blijken te zijn.

Nixon werd opgevolgd door vicepresident Gerald Ford (1913-2006). De neocons oefenden aanzienlijke druk uit op Ford om George Bush sr. (°1924) als nieuwe vicepresident aan te stellen, doch Ford ontstemde hen door voor de gematigder Nelson Rockefeller (1908-1979), ex-gouverneur van de staat New York, te kiezen. Daar ondanks Nixons aftreden het parlement en de media er bleven naar streven om hem voor het gerecht te brengen, verleende Ford in september 1974 een presidentieel pardon aan Nixon voor diens vermeende rol in het Watergate-schandaal. Ondanks de enorme impact van dit schandaal werden de wortels ervan nooit blootgelegd. Nixon bleef tot zijn dood in 1994 zijn onschuld volhouden, hoewel hij wel beoordelingsfouten in de aanpak van het schandaal toegaf. De resterende 20 jaar van zijn leven zou hij besteden aan het herstel van zijn zwaar gehavende imago.

Nixon werd opgevolgd door vicepresident Gerald Ford (1913-2006). De neocons oefenden aanzienlijke druk uit op Ford om George Bush sr. (°1924) als nieuwe vicepresident aan te stellen, doch Ford ontstemde hen door voor de gematigder Nelson Rockefeller (1908-1979), ex-gouverneur van de staat New York, te kiezen. Daar ondanks Nixons aftreden het parlement en de media er bleven naar streven om hem voor het gerecht te brengen, verleende Ford in september 1974 een presidentieel pardon aan Nixon voor diens vermeende rol in het Watergate-schandaal. Ondanks de enorme impact van dit schandaal werden de wortels ervan nooit blootgelegd. Nixon bleef tot zijn dood in 1994 zijn onschuld volhouden, hoewel hij wel beoordelingsfouten in de aanpak van het schandaal toegaf. De resterende 20 jaar van zijn leven zou hij besteden aan het herstel van zijn zwaar gehavende imago.

In oktober 1974 werd Nixon getroffen door een levensbedreigende vorm van flebitis, waarvoor hij geopereerd diende te worden. President Ford kwam hem bezoeken in het ziekenhuis, maar de Washington Post – opnieuw – vond het nodig om de zwaar zieke Nixon te bespotten. In het voorjaar van 1975 verbeterde Nixons gezondheid en begon hij aan zijn memoires te werken, hoewel zijn bezittingen opgevreten werden door onder meer hoge advocatenkosten. Op een bepaald moment had ex-president Nixon nog amper 500 dollar op zijn bankrekening staan. Vanaf augustus 1975 verbeterde zijn financiële toestand door een reeks interviews voor een Brits televisieprogramma en door de verkoop van zijn buitenverblijf. Zijn in 1978 verschenen autobiografie ‘RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon’ werd een bestseller.

Chinese staatsleiders als Mao Zedong en Deng Xiaoping bleven Nixon nog jarenlang dankbaar voor de verbeterde relaties met de VS en nodigden hem herhaaldelijk uit naar China. Nixon slaagde er pas halfweg de jaren 1980 in om zijn geschonden reputatie enigszins te herstellen na druk in de media becommentarieerde reizen naar het Nabije Oosten en de USSR.

President Ford en Kissinger zetten Nixons détente voort door onder meer de Helsinki-Akkoorden te sluiten met de USSR. En toen Israël bleef weigeren om vrede te sluiten met Egypte, schortte Ford in 1975 onder hevig protest der neocons gedurende 6 maanden alle Amerikaanse militaire en economische steun aan Israël op. Dit was een waar dieptepunt in de Israëlisch-Amerikaanse relaties.

4. De opmars van het neoconservatisme

Neocons als stafchef van het Witte Huis Donald Rumsfeld (°1932), presidentieel adviseur Dick Cheney (°1941), senator Jackson en diens medewerker Paul Wolfowitz duidden tijdens de regering-Ford (1974-1977) de USSR aan als ‘het Kwade’, ook al stelde de CIA dat er géén bedreiging uitging van de USSR en er geen enkel bewijs voor te vinden was. De CIA werd dan ook verweten – onder meer door de Straussiaanse neocon-hoogleraar Albert Wohlstetter (1913-1997) – dat het eventuele bedreigende intenties van de USSR onderschatte.

De Republikeinse Partij verloor door het Watergate-schandaal zwaar bij de parlementsverkiezingen van november 1974, waardoor de neocons de kans kregen om meer invloed te verwerven in de regering. Toen William Colby (1920-1996), hoofd van de CIA, bleef weigeren om een ad hoc studiegroep van externe experten het werk van zijn analisten te laten overdoen, ijverde Rumsfeld in 1975 met succes bij president Ford voor een grondige herschikking van de regering. Op 4 november 1975 werden in dit ‘Halloween Massacre’ diverse gematigde ministers en topambtenaren vervangen door neocons. Onder meer Colby werd vervangen door Bush sr. als hoofd van de CIA, Kissinger bleef minister van Buitenlandse Zaken maar verloor zijn functie van nationaal veiligheidsadviseur aan generaal Brent Scowcroft (°1925), James Schlesinger werd opgevolgd door Rumsfeld als minister van Defensie, Cheney kreeg Rumsfelds vrijgekomen plaats van stafchef van het Witte Huis en John Scali stond zijn plaats als ambassadeur bij de VN af aan Daniel Moynihan (1927-2003). Vicepresident Rockefeller kondigde tevens onder druk der neocons aan dat hij niet zou opkomen als running mate van Ford bij de presidentsverkiezingen van 1976.

Het nieuwe CIA-hoofd Bush sr. vormde de anti-USSR studiegroep Team B onder leiding van de joodse hoogleraar Russische geschiedenis Richard Pipes (°1923) om de intenties der USSR te ‘herbestuderen’. Alle leden van Team B waren a priori al anti-USSR gezind. Pipes nam op aanraden van Richard Perle Wolfowitz op in Team B. Het zwaar omstreden rapport uit 1976 van deze studiegroep beweerde “een ononderbroken streven van de USSR naar wereldhegemonie” en “een falen der inlichtingendiensten” vastgesteld te hebben.

Achteraf bleek Team B op alle vlakken volkomen fout geweest te zijn. De USSR had immers helemaal geen “toenemend BNP waarmee het zich steeds meer wapens aanschafte”, maar verzonk langzaam in economische chaos. Ook een vermeende vloot niet door radar detecteerbare kernonderzeeërs heeft nooit bestaan. Door deze pure verzinsels praatten de Straussianen de VS bijgevolg een fictieve bedreiging door ‘het Kwade’ aan. Team B’s rapport werd gebruikt om de massale (en onnodige) investeringen in bewapening te rechtvaardigen, die begonnen op het einde der regering-Carter (1977-1981) en explodeerden tijdens de regering-Reagan (1981-1989).

In de aanloop naar de presidentsverkiezingen van 1976 schoven de neocons ex-gouverneur van Californië én ex-Democraat (!) Ronald Reagan (1911-2004) naar voor als alternatief voor Ford, die onder meer zijn détente tegenover de USSR en het opschorten van de steun aan Israël werd verweten. Desondanks slaagde Ford er toch in om zich tot Republikeins presidentskandidaat te laten aanduiden. In de eigenlijke presidentsverkiezing verloor hij echter tegen de Democraat Jimmy Carter (°1924).

Binnen de door neocons geïnfiltreerde Republikeinse Partij kwam in de jaren 1970 de denktank American Enterprise Institute op. Deze telde invloedrijke neocon-intellectuelen als Nathan Glazer (°1924), Irving Kristol, Michael Novak (°1933), Benjamin Wattenberg en James Wilson (°1931). Zij beïnvloedden de traditioneel-conservatieve achterban der Republikeinen, waardoor het groeiende protestantse fundamentalisme aansloot bij het neoconservatisme. De protestant Reagan werd hierdoor in 1981 president en benoemde direct een reeks neocons (zoals John Bolton, Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz, Doug Feith, William Kristol, Lewis Libby en Elliot Abrams). Bush sr. werd vicepresident.

Binnen de door neocons geïnfiltreerde Republikeinse Partij kwam in de jaren 1970 de denktank American Enterprise Institute op. Deze telde invloedrijke neocon-intellectuelen als Nathan Glazer (°1924), Irving Kristol, Michael Novak (°1933), Benjamin Wattenberg en James Wilson (°1931). Zij beïnvloedden de traditioneel-conservatieve achterban der Republikeinen, waardoor het groeiende protestantse fundamentalisme aansloot bij het neoconservatisme. De protestant Reagan werd hierdoor in 1981 president en benoemde direct een reeks neocons (zoals John Bolton, Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz, Doug Feith, William Kristol, Lewis Libby en Elliot Abrams). Bush sr. werd vicepresident.

In plaats van détente kwam er nu een agressief buitenlands en fel anti-USSR beleid, dat sterk steunde op de Kirkpatrick-doctrine die de ex-marxiste en ex-Democrate (!) Jeane Kirkpatrick (1926-2006) in 1979 in haar spraakmakende artikel ‘Dictatorships and Double Standards’ in Commentary beschreef. Dit behelsde dat hoewel de meeste regeringen in de wereld autocratieën zijn én dat ook altijd waren, het mogelijk zou zijn om die op lange termijn te democratiseren. Deze Kirkpatrick-doctrine moest vooral dienen om de steun aan pro-Amerikaanse dictaturen in de Derde Wereld te rechtvaardigen.

Veel immigranten uit het Oostblok werden actief in de neocon-beweging. Zij waren eveneens hevige tegenstanders van détente met de USSR en beschouwden het progressisme als superieur. Podhoretz bekritiseerde bovendien in het begin der jaren 1980 de voorstanders van détente zeer scherp.

De Amerikaanse bevolking werd nu een nog grotere Sovjetbedreiging aangepraat: de USSR zou een internationaal terreurnetwerk sturen en dus achter de terreuraanslagen in de hele wereld zitten. Opnieuw deed de CIA dit af als onzin, maar verspreidde toch de propaganda van het “internationale Sovjet-terreurnetwerk”. Bijgevolg moest de VS reageren. De neocons werden nu democratische revolutionairen: de VS zou internationaal krachten steunen om de wereld te veranderen. Zo werden in de jaren 1980 de Afghaanse mudjaheddin zwaar gesteund in hun strijd tegen de USSR en de Nicaraguaanse Contra’s tegen de sandinistische regering-Ortega. Daarnaast startte de VS een wapenwedloop met de USSR, die echter tot grote begrotingstekorten en een stijgende overheidsschuld leidde: Reagans defensiebeleid deed immers de defensie-uitgaven met 40% stijgen in 1981-1985 en verdriedubbelde het begrotingstekort.

De opkomst der neocons leidde tot een jarenlange Kulturkampf in de VS. Zij verwierpen immers het schuldgevoel over de nederlaag in Vietnam, evenals Nixons buitenlandse beleid. Daarnaast ontstond er verzet tegen een actief internationaal optreden der VS en tegen de vereenzelviging van de USSR met ‘het Kwade’. Reagans buitenlands beleid werd bekritiseerd als agressief, imperialistisch en oorlogszuchtig. Bovendien werd de VS in 1986 door het Internationaal Gerechtshof veroordeeld voor oorlogsmisdaden tegen Nicaragua. Ook veel Centraal-Amerikanen veroordeelden Reagans steun aan de Contra’s en noemden hem een overdreven fanaticus die bloedbaden, martelingen en andere gruwelen over het hoofd zag. De Nicaraguaanse president Ortega gaf ooit aan te hopen dat God Reagan zou vergeven voor zijn “vuile oorlog tegen Nicaragua”.

Ook in de regering-Bush sr. (1989-1993) beïnvloedden neocons het buitenlands beleid. Bijvoorbeeld Dan Quayle (°1947) was toen vicepresident en Cheney minister van Defensie met Wolfowitz als medewerker. Wolfowitz verzette zich in 1991-1992 tegen Bush’ beslissing om het Iraakse regime niet af te zetten na de Golfoorlog van 1990-1991. Hij en Lewis Libby (°1950) stelden in 1992 in een rapport aan de regering ‘preventieve’ aanvallen om “de aanmaak van massavernietigingswapens te voorkomen” – tóen reeds! – en hogere defensie-uitgaven voor. De VS kampte door Reagans bewapeningswedloop echter met een enorm begrotingstekort.

Tijdens de regering-Clinton (1993-2001) werden de neocons verdreven naar de denktanks, waar een twintigtal neocons regelmatig samenkwam, onder meer om over het Nabije Oosten te praten. Een door Richard Perle geleidde neocon-studiegroep met onder meer Doug Feith en David Wurmser stelde in 1996 het betwiste rapport ‘A Clean Break: A New Strategy for Securing the Realm’ op. Dit adviseerde de net aangestelde Israëlische premier Benjamin Netanyahu een agressief beleid tegenover zijn buren: stopzetting van de vredesonderhandelingen met de Palestijnen, afzetting van Saddam Hoessein in Irak en ‘preventieve’ aanvallen tegen de Libanese Hezbollah, Syrië en Iran. Israël moest dus volgens dit rapport streven naar een grondige destabilisering van het Nabije Oosten om zijn strategische problemen op te lossen, doch Israël kon zo’n enorme ondernemingen niet aan.

In 1998 schreef de neocon-denktank Project for the New American Century een brief aan president Clinton om Irak binnen te vallen. Deze brief was ondertekend door een reeks vooraanstaande neocons: Elliott Abrams, Richard Armitage, John Bolton, Zalmay Khalilzad, William Kristol, Richard Perle, Donald Rumsfeld, Paul Wolfowitz en Robert Zoellick. Dit toont nogmaals aan dat deze ideeën bij het aantreden van de regering-Bush jr. zeker niet uit het niets kwamen.

De obsessie der neocons voor het Nabije Oosten is te herleiden tot hun liefde voor Israël. Veel neocons zijn immers van joodse afkomst en voelen zich verbonden met Israël en met de partij Likoed. De neocons menen verder dat in de unipolaire wereld van na de Koude Oorlog de VS zijn militaire macht moet gebruiken om zelf niet bedreigd te worden en om de parlementaire democratie en het kapitalisme te verspreiden. Ook het begrip ‘regime change’ komt van hen.

Hoewel de presidenten Reagan en Bush sr. al neocon-ideeën overnamen, triomfeerde het neoconservatisme pas echt onder president George Bush jr. (°1946), wiens buitenlands en militair beleid volledig gedomineerd werd door neocons. Tijdens de zomer van 1998 ontmoette Bush jr. op voorspraak van Bush sr. diens voormalige adviseur voor Sovjet- en Oost-Europese Zaken Condoleeza Rice op het landgoed van de familie Bush in Maine. Dit leidde er toe dat Rice Bush jr. zou adviseren inzake buitenlands beleid tijdens zijn verkiezingscampagne. Hetzelfde jaar werd ook Wolfowitz aangetrokken. Begin 1999 vormde zich een volwaardige adviesgroep voor buitenlands beleid, die grotendeels afkomstig was uit de regeringen-Reagan en -Bush sr. De door Rice geleide groep omvatte verder Richard Armitage (ex-ambassadeur en ex-geheim agent), Robert Blackwill (ex-adviseur voor Europese en Sovjetzaken), Stephen Hadley (ex-adviseur voor defensie), Lewis Libby (ex-medewerker van de ministeries van Buitenlandse Zaken en Defensie), Richard Perle (adviseur voor defensie), George Schultz (ex-adviseur van president Eisenhower, ex-minister van Arbeid, Financiën en Buitenlandse Zaken, hoogleraar en zakenman), Paul Wolfowitz (ex-medewerker van de ministeries van Buitenlandse Zaken en Defensie), Dov Zakheim (ex-adviseur voor defensie), Robert Zoellick (ex-adviseur voor en ex-viceminister van Buitenlandse Zaken). Bush jr. wou op deze manier zijn gebrek aan buitenlandse ervaring ondervangen. Deze adviesgroep voor buitenlands beleid kreeg tijdens de verkiezingscampagne in 2000 de naam ‘Vulcans’ toebedeeld.

Na Bush’ verkiezingsoverwinning kregen bijna alle Vulcans belangrijke functies in zijn regering: Condoleeza Rice (nationaal veiligheidsadviseur en later Minister van Buitenlandse Zaken), Richard Armitage (viceminister van Buitenlandse Zaken), Robert Blackwill (ambassadeur en later veiligheidsadviseur), Stephen Hadley (veiligheidsadviseur), Lewis Libby (stafchef van vicepresident Cheney), Richard Perle (bleef adviseur voor defensie), Paul Wolfowitz (viceminister van Defensie en later voorzitter van de Wereldbank), Dov Zakheim (opnieuw adviseur voor defensie), Robert Zoellick (presidentieel vertegenwoordiger voor Handelsbeleid en later viceminister van Buitenlandse Zaken).

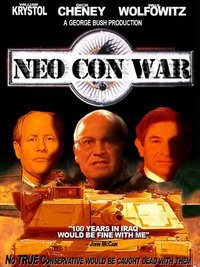

Ook andere neocons kregen hoge functies: Cheney werd vicepresident, terwijl Rumsfeld opnieuw minister van Defensie, John Bolton (°1948) viceminister van Buitenlandse Zaken, Elliot Abrams lid van de National Security Council en Doug Feith (°1953) presidentieel defensie-adviseur werden. Hierdoor was het Amerikaanse buitenlandse en militaire beleid volledig afgestemd op de geopolitieke belangen van Israël. Wolfowitz, Cheney en Rumsfeld waren de drijvende krachten achter de zogenaamde ‘Oorlog tegen het terrorisme’, die leidde tot de invasies van Afghanistan en van Irak.

Met het ‘Clean Break’-rapport uit 1996 (cfr. supra) was reeds 5 jaar vóór het aantreden van de regering-Bush jr. de blauwdruk van diens buitenlands beleid al ontworpen. Bovendien waren de 3 voornaamste auteurs van dit rapport – Perle, Feith en Wurmser – actief binnen deze regering als adviseur. Een herstructurering van het Nabije Oosten leek nu een stuk realistischer. De neocons stelden het voor alsof de belangen van Israël en de VS samenvielen. Het belangrijkste onderdeel van het rapport was de verwijdering van Saddam Hoessein als de eerste stap in de omvorming van het Israël-vijandige Nabije Oosten in een meer pro-Israëlische regio.