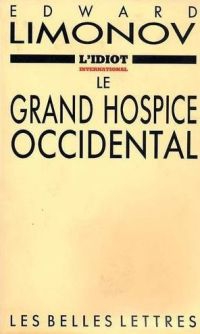

An Interview with Edward Limonov

The premier Italian daily, Il Corriere Della Serra, published a long interview with Edward Limonov by Paolo Valentino on two pages in its Sunday supplement, La Lettura, on 8 February 2015. The following was translated by Eugene Montsalvat from the French version.

In a year, Russian society has radically changed. We have lived with more than 20 years of humiliations, as a country and as a people. We have submitted to defeat after defeat. The country that Russia constructed, the Soviet Union, committed suicide. A suicide assisted by greedy foreigners. For 23 years we have remained in a full collective depression. The people of a great country constantly needs victories, not necessarily of a military nature, but it should see itself as a victor. The reunification of Crimea with Russia was seen by the Russians as the victory that we had lacked for so long. Finally! That was something comparable to the Spanish Reconquista.

– Edward Limonov

He has done everything and been everything in his life. Edouard Veniaminovitch Savenko, alias Edward Limonov. Ghetto thug, maybe KGB agent, beggar, vagabond, butler of a progressive American mogul, poet, writer in Parisian salons, irresistible seducer, sniper with Arkan’s Tigers at the time of the collapse of Yugoslavia, political leader, founder of the National Bolshevik Party before it dissolved, and he created the party The Other Russia.

But Limonov, sour as the citrus from which he takes his pseudonym, is above all an anti-hero, an aesthete, an outsider who has always chosen, voluntarily, the camp you shouldn’t choose, without ever being a loser for all that.

Basically, Edouard Limonov is a grand exhibitionist, who never feared the risks and paid the heavy price for all his adventures: for example, with two and a half years in prison, of which a dozen months were spent in Penal Colony Number 13, on the steppe near Saratov, in 2003.

It can seem paradoxical that for the first time in his life full of dangers, the personality made famous by the eponymous book by Emmanuel Carrère found himself more marginalized, in the catacombs of Russian national history, as a charismatic eccentric capable of leading a few dozen desperadoes. Fully on the contrary, he is today clearly in the mainstream, a champion of nationalist inspiration, which has spread in the collective spirit of the Russian nation due to the events in Ukraine and the reaction of the Western countries.

Limonov received us in his little apartment in the center of Moscow, near Mayakovsky Place. A large and robust young man picked us up a few streets from there, and led us to the building. Another beefy guy opened the armoured door. These are his militants, who serve as his bodyguards.

He will soon be 72, and, despite his silver hair, seems twenty years younger. Thin, narrow-faced with his famous goatee, and wearing a small earring, he is dressed all in black, with tight pants, a sleeveless vest, and a turtleneck sweater.

He spoke in a soft voice, slightly hoarse. He had a calm demeanour and a certain gentleness, in apparent contradiction with the furor that has marked his life.

‘You Westerners, you understand nothing of what happened’, he began, offering a glass of tea.

What don’t we understand?

What don’t we understand?

That Donbass is populated by Russians. And that there is no difference with the Russians who live in the neighbouring regions, in Russia, like Krasnodar or Stavropol: the same people, the same dialect, the same history. Putin is at fault for not saying it clearly to the USA and Europe. It is in our national interest.

So for you, Ukraine is Russia?

No, not entirely. Ukraine is a little empire, composed of territory taken from Russia, and others taken from Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Hungary. Its borders were the administrative frontiers of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Ukraine. Borders that never existed. It’s an imaginary territory, that, I repeat it, only exists due to administrative decrees.

Take Lviv, the city that is considered to be the the capital of Ukrainian nationalism: you know that Ukraine received it in 1939 with the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. At that time, 57% of the population was Polish, the rest principally Jewish, and there were practically no Ukrainians. The south of the country was then given to Ukraine after having been conquered by the Red Army. That’s history. But then, when Ukraine was separated from the Soviet Union, it did not return those territories, beginning with Crimea, which was given as a gift by Khrushchev in 1954. I do not understand why Putin has yet to say that Donbass and Russia, they’re the same thing.

Maybe because they are territories recognized at the international level.

When the territory of the Soviet Union was dismembered, in 1991, the international community mocked it. Did anyone say anything? No. That is what I reproach the West for: applying a double standard to international relations. There are certain rules for a country like Russia, and others for the West. There will not be peace in Ukraine so long as they won’t liberate their colonies, I mean Donbass. Putin is at fault for not saying it directly.

Maybe Putin does so because he doesn’t want to annex Donbass, as he did with Crimea, because that can only create problems?

Maybe you are right. Maybe he didn’t want to annex Crimea. That was his duty, whether it pleases him or not. He is the President of Russia. And he risked a lot.

A limited risk all the same, because his popularity remains above 80%.

He still benefits from the effects of the inertia created by Crimea. But if he abandons Donbass, by leaving it to the government of Kiev, with the thousands of Russian volunteers who risk being killed, his popularity will melt like snow in the Sun. For the moment, that doesn’t seem to be the case, but Putin is stuck.

What will he do, according to you?

He reacts well. He is in the process of radicalizing. He understood that the Minsk accords were a farce. They only aid the Ukrainian President, Poroshenko. Even if he doesn’t want to, he must act. A year ago, when the problem of Crimea arose, Putin was obsessed with the Olympic Games, which he considered as his great work. He was happy. He was obliged to put in practice the plans prepared by the Russian Army, that have evidently existed for a long time. Crimea was a victory for Putin, although despite himself. Donbass was not absolutely on the horizon. The Western countries accuse him of wanting to annex it, but in fact he is very hesitant.

After Ukraine, what will be the next territories that will be reconquered? The Baltic countries?

No, evidently not. To return to Ukraine, I believe that it should exist as a state, composed only of the Western provinces that can be considered as Ukrainian. It’s not that I want to deny their culture and their beautiful language. But I repeat it: on the condition that they liberate the Russian territories.

You have attacked Putin many times in the past. So is he the leader Russia needs, yes or no?

We have an authoritarian regime. And Putin is the leader that we have. There is no means to escape it. But there is a difference between the Putin of the first two elections and that of today. The first was catastrophic, given his inferiority complex of an old KGB petty officer. He liked the company of international leaders: Bush Jr., Schröder, Berlusconi. But he learned over time. He improved. He said goodbye to the glitter and began serious work. He is in a difficult time, and he does what is necessary. It is impossible today not to ask him to be authoritarian.

Can Russia be a non-authoritarian country?

If Obama continues to say that he must punish us, then this obliges us to have authoritarian leaders.

What does Russia represent for you?

The greatest European nation. We are twice as numerous as the Germans. Truly, we are Europe. The Western part is a little appendix, not only in terms of territory, but also in wealth.

In truth, the European Union is the number one commercial power in the world.

There are things more important than commerce and markets.

If you the the greatest European power, why are you also nationalists?

If you the the greatest European power, why are you also nationalists?

We are no more nationalists than are the French or Germans. We are a power more imperial than nationalist. I recall that more than 20 million Muslims live in Russia, but they are not immigrants, they have always been there. We are anti-separatist. Certainly, there is still an ethnic nationalism in Russia, luckily in the minority, and that creates problems. I am not a Russian nationalist and I have never been. I consider myself to be an imperialist. I want a country with all its diversity, but rallying to Russian civilisation, culture, and history. Russia can only exist as a mosaic.

But are you, or are you not, part of the Western world?

That is not important. It’s a dogmatic question, without real meaning. Is South Korea part of the Western world? No, and yet it is considered as such. Where is the border of the West? That is not important for Russians.

What distinguishes Russian identity?

Our history. We are not better than others, but not worse either. We do not accept being treated as inferiors, left to the side and humiliated. That enrages us. It’s our spiritual state today.

The West claims the values of the French Revolution: democracy, separation of powers, the rights of man. Is democracy part of your values?

For Russians, the most important and fundamental notion is that of spravedlivost. This means justice, in the senses of social justice, equity,and aversion to inequalities. I think that our spravedlivost is very close to what you call democracy.

The sanctions and the economic crisis, could they threaten Putin’s position?

I think that in the world today, economics is overvalued. It is the passions which are the motor of history. We can resist economic pressure, and we will resist. But will Putin do what he must do in Donbass? Look at our history: the Siege of Leningrad, the Battle of Stalingrad. We can do it. There were many throughout history who tried to beat us, from Napoleon to Hitler. But Russian national pride weighs more than political economy, and I think I know the character of my people well.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Si può comunque affermare con una certa sicurezza che attorno alla fine degli anni ’20 le tesi schmittiane subiscano un’evoluzione da una prima fase incentrata sulla “decisione” a una seconda che volge invece agli “ordini concreti”, per una concezione del diritto più ancorata alla realtà e svincolata non solo dall’eterea astrattezza del normativismo, ma pure dallo “stato d’eccezione”, assenza originaria da cui il diritto stesso nasce restando però co-implicato in essa.

Si può comunque affermare con una certa sicurezza che attorno alla fine degli anni ’20 le tesi schmittiane subiscano un’evoluzione da una prima fase incentrata sulla “decisione” a una seconda che volge invece agli “ordini concreti”, per una concezione del diritto più ancorata alla realtà e svincolata non solo dall’eterea astrattezza del normativismo, ma pure dallo “stato d’eccezione”, assenza originaria da cui il diritto stesso nasce restando però co-implicato in essa. Lo spazio, cardine di quest’impianto teorico, viene analizzato nella sua evoluzione storico-filosofica e con riferimenti alle rivoluzioni che hanno cambiato radicalmente la prospettiva dell’uomo. La modernità si apre infatti con la scoperta del Nuovo Mondo e dello spazio vuoto d’oltreoceano, che disorienta gli europei e li sollecita ad appropriarsi del continente, dividendosi terre sterminate mediante linee di organizzazione e spartizione. Queste rispondono al bisogno di concretezza e si manifestano in un sistema di limiti e misure da inserire in uno spazio considerato ancora come dimensione vuota. È con la nuova rivoluzione spaziale realizzata dal progresso tecnico – nato in Inghilterra con la rivoluzione industriale – che l’idea di spazio esce profondamente modificata, ridotta a dimensione “liscia” e uniforme alla mercé delle invenzioni prodotte dall’uomo quali «elettricità, aviazione e radiotelegrafia», che «produssero un tale sovvertimento di tutte le idee di spazio da portare chiaramente (…) a una seconda rivoluzione spaziale» (Ivi, p.106). Schmitt si oppone a questo cambio di rotta in senso post-classico e, citando la critica heideggeriana alla res extensa, riprende l’idea che è lo spazio ad essere nel mondo e non viceversa. L’originarietà dello spazio, tuttavia, assume in lui connotazioni meno teoretiche, allontanandosi dalla dimensione di “datità” naturale per prendere le forme di determinazione e funzione del “politico”. In questo contesto il rapporto tra idea ed eccezione, ancora minacciato dalla “potenza del Niente” nella produzione precedente, si arricchisce di determinazioni spaziali concrete, facendosi nomos e cogliendo il nesso ontologico che collega giustizia e diritto alla Terra, concetto cardine de Il nomos della terra, che rappresenta per certi versi una nostalgica apologia dello ius publicum europaeum e delle sue storiche conquiste. In quest’opera infatti Schmitt si sofferma nuovamente sulla contrapposizione terra/mare, analizzata stavolta non nei termini polemici ed oppositivi di Terra e mare

Lo spazio, cardine di quest’impianto teorico, viene analizzato nella sua evoluzione storico-filosofica e con riferimenti alle rivoluzioni che hanno cambiato radicalmente la prospettiva dell’uomo. La modernità si apre infatti con la scoperta del Nuovo Mondo e dello spazio vuoto d’oltreoceano, che disorienta gli europei e li sollecita ad appropriarsi del continente, dividendosi terre sterminate mediante linee di organizzazione e spartizione. Queste rispondono al bisogno di concretezza e si manifestano in un sistema di limiti e misure da inserire in uno spazio considerato ancora come dimensione vuota. È con la nuova rivoluzione spaziale realizzata dal progresso tecnico – nato in Inghilterra con la rivoluzione industriale – che l’idea di spazio esce profondamente modificata, ridotta a dimensione “liscia” e uniforme alla mercé delle invenzioni prodotte dall’uomo quali «elettricità, aviazione e radiotelegrafia», che «produssero un tale sovvertimento di tutte le idee di spazio da portare chiaramente (…) a una seconda rivoluzione spaziale» (Ivi, p.106). Schmitt si oppone a questo cambio di rotta in senso post-classico e, citando la critica heideggeriana alla res extensa, riprende l’idea che è lo spazio ad essere nel mondo e non viceversa. L’originarietà dello spazio, tuttavia, assume in lui connotazioni meno teoretiche, allontanandosi dalla dimensione di “datità” naturale per prendere le forme di determinazione e funzione del “politico”. In questo contesto il rapporto tra idea ed eccezione, ancora minacciato dalla “potenza del Niente” nella produzione precedente, si arricchisce di determinazioni spaziali concrete, facendosi nomos e cogliendo il nesso ontologico che collega giustizia e diritto alla Terra, concetto cardine de Il nomos della terra, che rappresenta per certi versi una nostalgica apologia dello ius publicum europaeum e delle sue storiche conquiste. In quest’opera infatti Schmitt si sofferma nuovamente sulla contrapposizione terra/mare, analizzata stavolta non nei termini polemici ed oppositivi di Terra e mare