It may have been the dawning sense of this new global “division of labour” that hastened the removal of the old colonial system from Africa rather than any impetus caused by the largely feeble efforts of African nationalism. Although colonialism certainly taught the African to hate the White man by driving home his inferiority in a number of key indices, anyone who has lived in Africa, as I have, will know that petty tribalism, and not broad-based nationalism, has been and is always likely to be the driving force in that considerable part of the world.

So, what use does the global economic order have for Africa? Sadly, the Africans are terrible producers, lacking the precision, conscientiousness, group ethic, and self-sacrificing qualities needed to constitute a hard-working, reliable industrial population. Not to mention the issue of IQ! They are equally inept when it comes to consumption, and not only because of their proverbial penury and otherwise laudable penchant for reusing every piece of junk that comes their way. Even when they have money to burn, they seem more attracted to simple bling than to acquiring the wide variety of gizmos, gadgets, home appliances, bric-a-brac, and exotic interests that support vast export industries. The lack of protection accorded property in Africa also plays an important role in disqualifying them from this key economic function.

This means that Africa’s economic destiny is simply to be a raw material source—oil, gas, minerals, and a few tropical crops—something for which its still relatively virgin vastness makes it an ideal candidate. In the past this was always the case, although then it was gold, ivory, and slaves that slowly turned the wheels of commerce. Nobody thought the continent was worth bothering about beyond this, especially the Sub-Saharan portion. That was until the discovery of the Americas, two virgin continents that proved eminently more developable.

The tragic shortage of labour in the fast developing New World, in large part caused by European diseases, led to the unfortunate institution of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, and while the labour mobilized at the crack of whip played a key role in working sugar cane plantations and silver mines, the partial success of the system also fostered the mistaken belief among Europeans that Africa and the Africans had the same sort of economic potential as anywhere and anyone else in the World. All it would take would be a few guns, Bibles, and copies of Samuel Smiles Self-Help to turn Bulawayo into Chicago.

This is how 19th-century colonialism really should be seen—as a vote of confidence by Europeans in the capabilities and ultimate potential of the Black man. Without the belief that the African could ultimately become just as economically upstanding as the European or Asian, the great 19th-century wave of colonization and investment in the Dark Continent would never have happened.

Harold Macmillan’s Winds of Change speech probably marks the point when European colonialists and capitalists realized that the game was up and that, for one reason or another, Africa was never going to be America or Japan, leapfrogging from wilderness or agrarian backwater to economic greatness.

Once the colonialists upped sticks, merely allowing Africa to revert to its wild state was not an option. In the period before colonization, various goods from the interior had naturally trickled down to the European and Arab trading posts and forts dotted along the coast. However, in the post-colonial period the kind of amounts produced by this process were wholly insufficient. Although the flags were lowered, Africa had to be kept on tap. This is what determined the characteristics of Neocolonialism: a system that could get the raw materials out more efficiently than the natives would left to themselves. Absolute efficiency was not required as that would simply flood the market and reduce profits, but some quickening of Africa’s natural tendencies was required.

The characteristics of the system of Neocolonialism that emerged included:

-

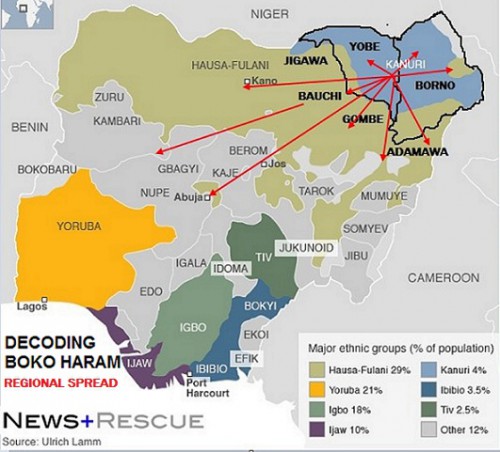

Creating and maintaining vast ethnic and tribal patchwork states that ignored the principle of local self-determination

-

Fostering tribal divisions to keep the states weak, encourage tyranny, and to exert leverage on the rulers

-

Various forms of bribery, including corporate bribery, foreign “aid,” and other incentives

-

Granting major Western corporations carte-blanche exploitation rights and allowing them access to cheap unskilled labour to supplement imported skilled labour

-

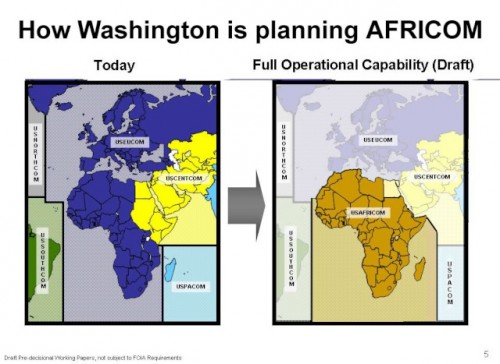

Occasional, low-key military intervention

The most successful African dictators, like the Congo’s Joseph Mobutu and Ivory Coast’s Félix Houphouët-Boigny, realized that their role was to facilitate raw material extraction, rather than develop their countries or challenge the ex-colonial masters. They instinctively understood that their slice of the profits should be used in ways the Neocolonialists found non-threatening—depositing the money in Swiss banks, for example, importing European haute-couture, or building shining palaces or cathedrals in the jungle.

Joseph Mobutu and Richard Nixon, 1973

But Neocolonialism could only work when applied to weak states, of which Africa has plenty. Some African rulers, buoyed up by Islam, Communism, or Arab Nationalism, could escape its grasp. Examples here include Nasser in Egypt, Gaddafi in Libya, and Mengistu in Ethiopia. Against such rulers, Neocolonialism could do little except play a waiting game.

Nor was Neocolonialism always negative. Under its first president Houphouët-Boigny, Ivory Coast saw particularly good relations with its ex-colonial power, France, and the development of the country’s coffee and cocoa crops, with a large influx of foreign labour from poorer Northern countries like Burkina Faso and French experts who helped run everything from the army and economic planning to the cocoa harvest. This gave the country one of the highest standards of living in post-colonial Africa, leading to the term “The Ivorian Miracle,” although problems started to set in following the slump in the price of its main export cocoa in the 1980s.

Many of the coups and revolutions in post-colonial African history that otherwise look so random and pointless, and seem like the result of tribalism or over-ambitious army officers, start to make more sense in the context of Neocolonialism. Ivory Coast is a good example. In 1999, Houphouët-Boigny’s successor, Henri Konan Bédié, was removed by a coup; while in 2002 an attempted coup tried to remove Laurent Gbagbo, and ended up splitting the country into Northern and Southern halves. Unlike their esteemed predecessor, both these leaders succeeded in antagonizing France, most noticeably by attempting to shore up their positions through mobilizing resentment against immigrant labourers and foreign economic interests.

But old-fashioned Neocolonialism of the type that was behind removing Bédié and putting and keeping Mabuto in power in the Congo had to rely on low-key opportunism and subtle methods. The public back home could not be made too aware of the bribery, contacts with thugs and tyrants, weapons smuggling, and occasional employment of small groups of mercenaries. The environment of the Cold War also meant that Neocolonialism had to tread softly, so much so that even petty dictators like Robert Mugabe, who could benefit from the crutch of having a White population to oppress, were able to defy it.

But the soaring need for African commodities combined with the festering apathy of Africans, who, after 50 years of being tyrannized and brutalized by their own kind, have largely lost their faith in the dream of independence, has led to a major revamping of Neocolonialism, so much so that it has effectively become something else that can best be termed “Global-colonialism” because (a) it is designed to subordinate Africa to the global division of economic functions, (b) the moral justification for the system hinges on globalist “humanitarian values,” and (c) its chief agents are the key globalist nations, America, Britain and France.

The system retains many of the methods of Neocolonialism, including setting tribe against tribe, extensive bribery, weapons smuggling, and giving the green light to those with their own axe to grind. But there are also important differences:

- Unlike Neocolonialism, which preferred long-term rulers and only sought to remove leaders who were uncooperative, Global-colonialism has a preference for shorter-term leaders and places more emphasis on elections. This actually creates more leverage as rulers constantly need the endorsement of the West. Even if elections produce the “wrong” result, they can always be declared invalid due to ballot fraud or corruption as these phenomena are always present in any African election.

- While Neocolonialism tended to be low-key and avoided publicity, Global-colonialism is noisy and demonstrative. It always tries to involve the media, which is one of its key arms. (In the event that the individuals and groups it elevates turn out to be Al-Qaeda sympathizers or genocidal thugs, expect Orwellian U-turns and the full exploitation of the public’s short attention span and near total ignorance of Africa.)

- Global-colonialism is prepared to use much greater military force. This includes the smuggling of larger quantities of arms than before, as well as higher calibre weapons, such as the Ukrainian tanks the U.S. was caught smuggling to the Southern Sudanese rebels through Kenya in 2008. It also includes direct military intervention of the kind that removed Gbagbo and prevented Gaddafi crushing the Libyan rebellion. There is a preference for air power and specialist ground forces rather than the kind of heavily involved military intervention that has occurred in other parts of the world. Cost may be a factor. Nevertheless, this is certainly a step up from the old days of “The Dogs of War.”

- To justify such military action, “human rights” and “protecting the civilian population” are tirelessly invoked. However, such “Totalitarian Humanism” can be applied very selectively, as we see in the case of Ivory Coast, where massacres by the French- and UN-approved rebels did not result in any military action being taken except on behalf of the same rebels.

- There is a willingness to change borders as seen in Sudan and the suggestion that Libya too might be partitioned.

- Perhaps because the system is new, Global-colonialism places great importance on getting someone—indeed anyone—to sign the chit for its actions. This is supposed to give a disinterested gloss to any intervention. Ideally, the signer should be the United Nations, but other suitable candidates include the African Union, the Arab League, or even, I suspect, the local chapter of the Abidjan Boy Scouts.

Global-colonialism can be seen as a combination of three separate pre-existing strands: (i) Neocolonialism, (ii) the kind of humanitarian intervention pioneered by the United Nations Mission to Sierra Leone in 1999, and (iii) a more cynical but equally virulent form of the old neocon crusading spirit.

The element of humanitarian intervention, oddly enough, has rock n’ roll roots, stemming from the naïve do-goodism of Bob Geldof’s Live Aid and other efforts by pop stars like Bono to “improve” the world without touching their own bank balances. This has played a significant role in seeding the idea among the wider public and giving Global-colonialism its strong pseudo moral imperative.

Given Neocolonialism’s preference for large ethnic patchwork states, Global-colonialism’s willingness to change borders is noteworthy. This has its precedents in the campaign to help the Kosovars and Montenegrins break away from Serbia, but seeing this concept applied to Africa in the case of Sudan is intriguing. If followed to its logical conclusion, the decision to support the creation of new states based on local ethnic factors would lead to practically every border in Africa being redrawn, with the creation of dozens, if not hundreds, of new statelets. Clearly this would remove a useful mechanism for imposing effective tyrannies over large areas or destabilizing and removing leaders it did not like, so why has Global-colonialism supported it in this case?

The PR men for Global-colonialism would claim that, after decades of civil war and millions of deaths, partition is the only way to “save human lives” and achieve a “lasting peace.” But this ignores the fact that both the states created by this division will still be ethnic patchworks. A more likely explanation is that, in addition to wishing to humiliate Khartoum, the Global-colonialists are simply removing an overly polarizing division that serves to unite the diverse groups on either side of the divide. With the non-Muslims in the South out of the way, the simmering divisions between the Muslim Furs, Nubians, Bejas, and various Arab-speaking groups in the North will move to the fore; while, in the same way, in the new state of South Sudan ethnic divisions long suppressed by the need to fight Islamic oppression will also bubble to the surface. This, in effect, creates much better conditions for the profitable exploitation of the oil fields in the region.

The PR men for Global-colonialism would claim that, after decades of civil war and millions of deaths, partition is the only way to “save human lives” and achieve a “lasting peace.” But this ignores the fact that both the states created by this division will still be ethnic patchworks. A more likely explanation is that, in addition to wishing to humiliate Khartoum, the Global-colonialists are simply removing an overly polarizing division that serves to unite the diverse groups on either side of the divide. With the non-Muslims in the South out of the way, the simmering divisions between the Muslim Furs, Nubians, Bejas, and various Arab-speaking groups in the North will move to the fore; while, in the same way, in the new state of South Sudan ethnic divisions long suppressed by the need to fight Islamic oppression will also bubble to the surface. This, in effect, creates much better conditions for the profitable exploitation of the oil fields in the region.

Global-colonialism means that no African ruler can now count himself safe. This was vividly demonstrated in Côte d'Ivoire, where Laurent Gbagbo was perhaps its first clear-cut scalp. Having displeased the French with his anti-immigrant and anti-French populism, he suffered an old style Neocolonialist coup in 2002 that didn’t quite work. After a stand-off lasting several years that was resolved by an agreement to hold an election, the campaign against him then entered a new phase that was clearly Global-colonialist in character.

After a disputed election result, Gbagbo’s authority was undermined by foreign criticism and calls for him to stand down, immediately followed by a military push from the Northern rebels supported by France and then the UN, along with a media blitz. At the same time that NATO was bombing Libya to “protect human life,” the rebel forces on their way south committed massacres, most notably at the town of Duekoue, but rather than NATO or even France bombing the roads carrying the rebels south, the issue was fudged and forgotten, allowing the perpetrators to close in on Gbagbo’s power base of Abidjan.

With the rebels unable to storm the president’s heavily-defended compound, French ‘peacekeepers’ in the country since 2002, along with some Ukrainian helicopter gun-ships under the auspices of the UN, blew away Gbagbo’s heavy defences, leading to his capture. There have also been rumours that rather than the undisciplined rebel forces, it was actually French specialist ground troops who delivered the coup de grâce. Either way, the rebel leader and the new president, Alassane Ouattara, with his immigrant origins, ties to the old Houphouët-Boigny regime, and French-Jewish wife is much more to the tastes of the old Neocolonialists as well as the new Global-colonialists.

With successes in The Sudan and the Ivory Coast, the new paradigm of Global-colonialism has so far been proving itself effective. Cheaper than full-scale war, but with more cutting edge than Neocolonialism, Global-colonialism seems the ideal tool for integrating Africa’s resources into the global economy.

Of the three cases mentioned, Libya is obviously proving the more difficult one, but even here the removal of half the country from the control of Gaddafi must be counted a success. This is the kind of result that Neocolonialism could never have achieved. The Gaddafi clan may hang on. They may even regain control over the rebel-held part of the country. But, even if they do, they will be much weaker than they were before and may well decide to follow the route of Mabuto and Houphouët-Boigny, especially as the next generation of the clan is likely to lack the Quixotic tendencies of its founder.

In its early days Gaddafi’s regime gave a glimpse of what a new kind of radical African nationalism might be like. Rather than spending the nation’s oil revenue on the bling that attracted other African leaders, Gaddafi used it to stir up trouble and challenge the status quo, rather like a latter day Hannibal taking on the Roman Empire. This was possible in the post-colonial age when Neocolonialism had to tread lightly and pull its punches, but now recalcitrant African leaders face a different beast, armed with longer teeth and sharper claws and the kind of PR that makes it seem all fuzzy and cute. Back in the ‘50s and ‘60s, the Wind of Change ruffled the coat tails of a departing colonial order, but now, the hurricane of Global-colonialism is blowing the other way.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

To paraphrase Harold Macmillan, a “wind of change” is blowing through Africa. But, unlike 1960, when the former British Prime Minister made his famous remark, the wind today is not that of a growing national consciousness in the mud huts and shanty-towns, but instead the stiff breeze of a new kind of Neocolonialism.

To paraphrase Harold Macmillan, a “wind of change” is blowing through Africa. But, unlike 1960, when the former British Prime Minister made his famous remark, the wind today is not that of a growing national consciousness in the mud huts and shanty-towns, but instead the stiff breeze of a new kind of Neocolonialism.

.jpg)