Author’s Note:

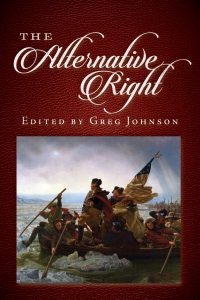

This is the opening essay of a forthcoming anthology called The Alternative Right.

The Alternative Right does not have an essence, but it does have a story, a story that begins and ends with Richard Spencer. The story has four chapters.

First the term “Alternative Right” was coined in 2008. Then the Alternative Right webzine was launched on March 1, 2010 and ran until December 25, 2013. When it was first coined, the Alternative Right simply referred to an alternative to the American conservative mainstream. When it became the name of a publication, it functioned as a broad umbrella term encompassing such schools of thought as paleoconservatism, libertarianism, race-realism, the European New Right, Southern Nationalism, and White Nationalism. By the time the Alternative Right webzine was shut down, however, the term Alt Right had taken on a life of its own. It was not just the name of a webzine, but a generic term for Right-wing alternatives to the conservative mainstream.

The second chapter is the emergence in 2015 of a vital, youth-oriented, largely online Right-wing movement. This movement encompassed a wide range of opinions from White Nationalism and outright neo-Nazism to populism and American civic nationalism. Thus this movement quite naturally gravitated to the broad generic term Alt Right. The new Alt Right threw itself behind Donald Trump’s run for the presidency soon after he entered the race in 2015 and became increasingly well-known as Trump’s most ferocious defenders in online battles, to the point that Hillary Clinton actually gave a speech attacking the Alt Right on August 25, 2016.

The second chapter is the emergence in 2015 of a vital, youth-oriented, largely online Right-wing movement. This movement encompassed a wide range of opinions from White Nationalism and outright neo-Nazism to populism and American civic nationalism. Thus this movement quite naturally gravitated to the broad generic term Alt Right. The new Alt Right threw itself behind Donald Trump’s run for the presidency soon after he entered the race in 2015 and became increasingly well-known as Trump’s most ferocious defenders in online battles, to the point that Hillary Clinton actually gave a speech attacking the Alt Right on August 25, 2016.

The third chapter is the Alt Right “brand war” of the fall of 2016. The Alt Right “brand” had become so popular that it was being widely adopted by Trumpian civic nationalists, who rejected the racism of White Nationalists. White Nationalists began to worry that their brand was being coopted and started to push back against the civic nationalists. The brand war ended on November 21, 2016 at a National Policy Institute conference with the incident known as Hailgate [2], in which Richard Spencer uttered the words “Hail Trump, hail our people, hail victory!” and raised his whiskey glass in a toast, to which some people in the audience responded with Hitler salutes. When video of this went public, civic nationalists quickly abandoned the Alt Right brand, and the “Alt Lite” was born.

The fourth chapter is the story of the centralization and decline of the Alt Right, largely under the control of Richard Spencer. This period was characterized by polarization and purges, as well as the attempt to transform the Alt Right from an online to a real-world movement, which culminated at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia on August 11–12, 2017. Both trends led the Alt Right to shrink considerably. Some abandoned the brand. Others abandoned the entire movement. The remnant has retreated back to its strongholds on the internet. As of this writing, there is no fifth chapter, and the Alt Right’s future, if any, remains to be seen. Like cancer, there may be no stage five.

1. The Invention of a Brand

The Alternative Right brand first emerged in the fuzzy space where the paleoconservative movement overlaps with White Nationalism. The term “paleoconservatism” was coined by Paul Gottfried, an American Jewish political theorist and commentator. Paleoconservatism defined itself as a genuinely conservative opposition to the heresy of neoconservatism.

The paleoconservative movement was a safe space for the discussion and advocacy of everything that neoconservatism sought to abolish from the conservative movement: Christianity, tradition, America’s white identity, an America-first foreign policy, immigration restriction, opposition to globalization and free trade, the defense of traditional/biological sexual roles and institutions, and even—although mostly behind closed doors—biological race differences and the Jewish question.

Aside from Gottfried, the leading paleocons included Samuel Francis, who openly associated with White Nationalists; Joseph Sobran, who was purged from National Review for anti-Semitism and who also openly associated with White Nationalists; and Patrick Buchanan, who stayed closer to the political mainstream but was eventually purged from MSNBC for “racism” because his book Suicide of a Superpower [3] defended the idea of the United States as a normatively white society.

William H. Regnery II (b. 1941) is a crucial figure in the rise of the Alt Right because of his work in creating institutional spaces in which paleoconservatives and White Nationalists could exchange ideas. Lazy journalists repeatedly refer to Regnery as a “publishing heir.” In fact, his money came from his grandfather William H. Regnery’s textile business. The conservative Regnery Publishing house was founded by Henry Regnery, the son of William H. Regnery and the uncle of William H. Regnery II. (In 1993, the Regnery family sold Regnery Publishing to Phillips Publishing International.)

In 1999–2001, William H. Regnery II played a key role in founding the Charles Martel Society, which publishes the quarterly journal The Occidental Quarterly, currently edited by Kevin MacDonald. In 2004–2005, Regnery spearheaded the foundation of the National Policy Institute, which was originally conceived as a vehicle for Sam Francis, who died in February of 2005. NPI was run by Louis R. Andrews until 2011, when Richard Spencer took over. Both the Charles Martel Society and the National Policy Institute are White Nationalist in orientation. The Occidental Quarterly is also openly anti-Semitic.

But at the same time Regnery was involved with CMS and NPI, he was also working with Jewish paleocon Paul Gottfried to create two academic Rightist groups that were friendly to Jews. First, there was the Academy of Philosophy and Letters,[1] [4] of which Richard Spencer was reportedly a member.[2] [5] But Regnery and Gottfried broke with the Academy of Philosophy and Letters over the issue of race, creating the H. L. Mencken Club, which Gottfried runs to this day.[3] [6] The Mencken Club, like the Charles Martel Society and NPI, is a meeting ground for paleoconservatives and White Nationalists, although it is also friendly to Jews.

Richard Spencer began as a paleoconservative, entered Regnery’s sphere of influence, and emerged a White Nationalist. In 2007, Spencer dropped out of Duke University, where he was pursuing a Ph.D. in modern European intellectual history. From March to December of 2007, Spencer was an assistant editor at The American Conservative, a paleoconservative magazine founded in 2002 by Scott McConnell, Patrick Buchanan, and Taki Theodoracopulos in opposition to the neocon-instigated Iraq War. By the time Spencer arrived, however, Buchanan and Taki had departed. After being fired from The American Conservative, Spencer went to work for Taki, editing his online magazine Taki’s Top Drawer, later Taki’s Magazine, from January of 2008 to December of 2009. Taki thought his magazine was stagnant under Spencer’s editorship, so they parted ways. With money raised through Regnery’s network, Richard Spencer launched a new webzine, Alternative Right (alternativeright.com) on March 1, 2010.

The phrase “alternative right” first appeared at Taki’s Magazine under Spencer’s editorship. On December 1, 2008, Spencer published Paul Gottfried’s “The Decline and Rise of the Alternative Right [7],” originally given as an address at that year’s H. L. Mencken Club conference in November. Spencer claims credit for the title and thus the phrase “alternative right,” while Gottfried claims that they co-created it.[4] [8] The Alternative Right in decline is, of course, the paleoconservative movement. The Alternative Right on the rise is the more youthful post-paleo movement crystallizing at the Mencken Club and allied forums. The Alternative Right webzine was to be their flagship.

The Alternative Right webzine had an attractive design and got off to a strong start. I particularly respected Spencer’s decision to publish Steve McNallen and Jack Donovan, important writers who were anathema to Christians and paleocons. But after about six months, the site seemed to lose energy. Days would go by without new material, which is the key to building regular traffic, and matters were not helped by the site layout. Instead of simply putting new material at the top of a blog roll, the site had a host of departments, so one had to click six or eight links to discover that there was no new material. After doing this for a couple of weeks, readers would stop coming, waiting to hear about new material by email or on social media. By the beginning of 2012, Spencer had lost interest in editing the webzine. On May 3, 2012, he stepped down and handed the editorship to Andy Nowicki and Colin Liddell.

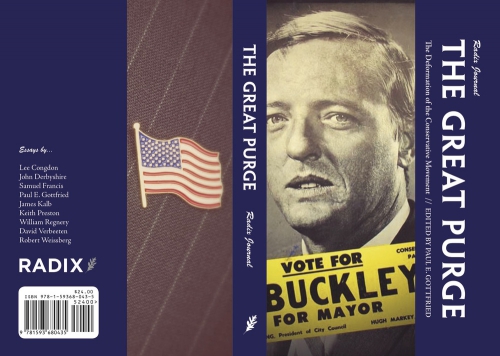

However, in 2013, Spencer was embarrassed by negative press coverage of one of Liddell’s articles and realized that he would always be linked to Alternative Right, even though he no longer had control of its contents. On Christmas day of 2013, Spencer shut Alternative Right down without consulting or warning Nowicki and Liddell. The domain address was repointed to Spencer’s new webzine, Radix Journal, which would never become a household name. Then, after another strong start, Radix too slumped into a low-energy site.

Nearly four years of articles and comments at Alternative Right—the collective contributions of hundreds of people—simply vanished from the web. Nowicki and Liddell salvaged what they could and carried on with the Alternative Right brand at blogspot.com, although their site had few readers and little influence. In 2018, embarrassed by the decline of the Alt Right brand, they changed the name to Affirmative Right.

Spencer’s greatest mistake in shutting down Alternative Right was not his high-handed manner, which caused a good deal of bitterness, but the fact that he pulled the plug after its name had become a generic term. Just as the brand “Xerox” became a term for photocopying in general, the brand “Hoover” became a verb for vacuuming in general, Sony’s “Walkman” became a generic term for portable cassette players, and “iPod” became a generic term for portable mp3 players, the Alt Right had become a generic term for a whole range of radical alternatives to mainstream conservatism. Imagine Xerox rebranding with a weird sounding Latinate name like Effingo once it had become synonymous with its entire industry.

The beauty of the Alt Right brand is that it signaled dissidence from the mainstream Right, without committing oneself to such stigmatized ideas as White Nationalism and National Socialism. As I put it in an article hailing Alternative Right to my readers at TOQ Online:

I hope that Alternative Right will attract the brightest young conservatives and libertarians and expose them to far broader intellectual horizons, including race realism, White Nationalism, the European New Right, the Conservative Revolution, Traditionalism, neo-paganism, agrarianism, Third Positionism, anti-feminism, and right-wing anti-capitalists, ecologists, bioregionalists, and small-is-beautiful types. . . . The presence of articles by Robert Weissberg and Paul Gottfried indicates that Alternative Right is not a clone of TOQ or The Occidental Observer. (Not that anybody expected that, although some might applaud it.) But that is fine with me. It is more important to have a forum where our ideas interface with the mainstream that to have another Occidental something-or-other.com.[5] [9]

Obviously, a term as useful as Alternative Right was going to stick around, even after being abandoned by its creator. Writers at Counter-Currents, the Alternative Right blogspot site, and even Radix kept the concept of the Alt Right in circulation in 2014 and the early months of 2015, after which it caught on as the preferred name of a new movement.

2. The Emergence of a Movement

The second phase of the Alt Right was quite unlike the first. The new Alt Right had different ideological origins, different platforms, and a radically different ethos. But it rapidly converged on White Nationalism and carried off some of its best ideas, as well as the term Alt Right. Then it became an international media phenomenon.

In terms of ideology, the first Alt Right was heavily influenced by White Nationalism and paleoconservatism. But the new Alt Right emerged largely from the breakdown of the Ron Paul movement, specifically the takeover of the libertarian movement by cultural Leftists, which drove culturally more conservative libertarians to the Right. (In 2009, I predicted that people in the Ron Paul movement would start moving toward white identity politics, so I sponsored an essay contest on Libertarianism and Racial Nationalism at The Occidental Quarterly, which I edited at the time, to develop arguments to ease the conversion of libertarians.[6] [10]) Other factors driving the emerging racial consciousness of this group were the Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown controversies, the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, and the beginning of the migrant crisis in Europe.

The first Alt Right emerged from a milieu of dissident book publishers and print journals, quasi-academic conferences where speakers wore coats and ties, and middle to highbrow webzines. The new Alt Right emerged on social media, discussion forums, image boards, and podcasts, with the webzines coming later. The most influential incubators of the new Alt Right were 4chan and 8chan, Reddit, and The Right Stuff, especially its flagship podcast, The Daily Shoah, and affiliated discussion forums.

The new Alt Right also had a very different ethos and style. While the first Alt Right published reasonable and dignified articles on webzines, the new Alt Right’s ethos was emerging from flame wars in the comment threads below. Whereas the first Alt Right cultivated an earnest tone of middle-class respectability, avoiding racial slurs and discussing race and the Jewish question in terms of biology and evolutionary psychology, the new movement affected an ironic tone and embraced obscenity, stereotypes, slurs, and online trolling and harassment.

There were also generational differences between the two Alt Rights. The first Alt Right was the product of a Gen-Xer under the patronage of people born in the Baby Boom and before, who actually had memories of America before the cultural revolution of the 1960s and the massive demographic shifts after 1965, when America opened its borders to the non-white world. The new Alt Right consisted primarily of Millennials and Gen-Zs, some of them as young as their early teens, who were products of a multicultural America with rampant social and familial decay, sexual degeneracy, and drug and alcohol abuse. The first group tended to be conservative, because they had memories of a better country. The latter group had no such memories and tended toward radical rejection of the entire social order.

In 2013, I argued that White Nationalists needed to reach out to significant numbers of white Millennials who had graduated from college during the Obama years, often with crushing debts, and who found themselves unemployed or underemployed, and frequently ended up living at home with their parents.[7] [11] I believed that White Nationalists had better explanations for and solutions to their plight than the Occupy Movement, and this “boomerang generation” could be an ideal “proletariat,” because they were highly educated; they were from middle and upper middle class backgrounds; they had a great deal of leisure time, much of which they spent online; and they were angry and disillusioned with the system, and rightly so.

As is so often the case, our movement’s outreach gestures went nowhere, but the logic of events drove these people in our direction anyway. Boomerang kids became a core group of the new Alt Right known as the “NEETs”—an acronym for Not in Education, Employment, or Training. When these NEETs and their comrades focused their wit, intelligence, anger, tech savvy, and leisure time on politics, a terrible beauty was born.

The Gamergate controversy of 2014 was an important trial run and tributary to what became the new Alt Right in 2015. Gamergate was a leaderless, viral, online populist insurrection of video gaming enthusiasts against arrogant Leftist SJWs (Social Justice Warriors) who were working to impose political correctness on gaming. Gamergate activists turned the tables on bullying SJWs, brutally trolling and mocking them and relentlessly exposing their corruption and hypocrisy. Gamergate got some SJWs fired, provoked others to quit their jobs, and went after the advertisers of SJW-dominated webzines, closing some of them down.[8][12]

Gamergate is important because it showed how an online populist movement could actually roll back Leftist hegemony in a specific part of the culture. Although not everyone involved in Gamergate went on to identify with the Alt Right, many of them did. A leading Gamergate partisan, for instance, was Milo Yiannopoulos of Breitbart, who later gave favorable press to the Alt Right and is now a prominent Alt Lite figure. Moreover, Alt Rightists who had nothing to do with Gamergate eagerly copied and refined its techniques of online activism. Indeed, I would argue that Gamergate was the moral and organizational model for the Disney Star Wars boycott of 2018, which tanked the movie Solo [13] and cost Disney hundreds of millions of dollars in lost revenue.

One of the best ways to understand the evolution of the new Alt Right is to read The Right Stuff and listen to The Daily Shoah from its founding in 2014 through the summer of 2015, when Donald Trump declared his candidacy for the President of the United States. The members of The Daily Shoah Death Panel began as ex-libertarians and “edgy-Republicans” and educated themselves about race realism and the Jewish question week after week, bringing their ever-growing audience along with them. In February of 2015, Mike Enoch attended the American Renaissance conference and afterwards started calling himself a White Nationalist.

By the spring of 2015, this new movement was increasingly comfortable with the term Alt Right.

When Donald Trump declared his candidacy for the US Presidency on June 16, 2015, most White Nationalist currents found common cause in promoting his candidacy. Trump advocacy encouraged cooperation and collegiality within the movement and provided a steady stream of new targets for creative memes and trolling, and as Trump’s candidacy ascended, the new Alt Right ascended with him.

In July of 2015, in the runup to the Republican Primary debates, the new Alt Right scored a major victory by injecting a meme that changed the mainstream political conversation: “cuckservative.” The inception of this meme was at Counter-Currents when on May 2, 2014, Gregory Hood referred to “cuckhold conservatives like Matt Lewis.”[9] [14] At this point, many in the media and political establishment realized that a genuine alternative to the mainstream Right had arrived.

The new Alt Right became skilled in using social media to solicit attention and promote backlashes from mainstream media and politicians. This attention caused the movement to grow in size and influence, reaching its peak when Hillary Clinton gave her speech denouncing the Alt Right on August 25, 2016.

An older generation of white advocates saw the notoriety of the Alt Right as an opportunity to reach new audiences. Jared Taylor, who was never thrilled with the Alt Right label, wrote about “Race Realism and the Alt Right.”[10] [15] Kevin MacDonald wrote about “The Alt Right and the Jews.”[11] [16] Peter Brimelow spoke at National Policy Institute conferences. David Duke began circulating memes.

Although I prefer to describe myself with much more specific terms like White Nationalism and the New Right, I always appreciated the utility of a vague term like Alt Right, so I allowed its use at Counter-Currents and occasionally used it myself. But whenever I use “we” and “our” here, I am referring to White Nationalism and the New Right, not the fuzzy-minded civic nationalists and Trumpian populists who also came to use the term Alt Right.

Some have dismissed the Alt Right as a Potemkin movement because it was small, existed largely online, and grew by provoking reactions from the mainstream. But this ignores the fact that America is ruled by a tiny elite employing soft power propagated by the media. So if the Alt Right is somehow illegitimate, so is the entire political establishment. The new Alt Right was a perfect mirror image of the establishment media: it was a metapolitical movement that promoted political change by transforming values and perceptions, but it was promoting change in the opposite direction by negating the establishment’s values and worldview.

The Alt Right’s particular tactics were dictated by the asymmetries between itself and the mainstream media. They had billions of dollars and armies of professional propagandists. We had no capital and a handful of dedicated amateurs. But new software gave us the ability to create quality propaganda at home, and the Internet gave us a way to distribute it, both at very little cost. The establishment’s vast advantages in capital and personnel were also significantly negated by the facts that the multicultural consensus it promotes is based on falsehoods and can only cause misery, and the people who control it are weakened by arrogance, smugness, and degeneracy. They are easily mocked and triggered into self-defeating behavior. Our great advantage was telling the truth about liberalism and multiculturalism and proposing workable alternatives. As long as we could stay online, and as long as we attacked from our strengths to their weaknesses, we went from success to success.

But many in the movement were not psychologically ready for success.

Notes

[1] [17] https://philosophyandletters.org/ [18]

[2] [19] https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/aramroston/hes-spent... [20]

[3] [21] http://hlmenckenclub.org/ [22]

[4] [23] Thomas J. Main, The Rise of the Alt-Right (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2018), p. 63.

[5] [24] Greg Johnson, “Richard Spencer Launches Alternative Right,” TOQ Online, March 2, 2010, https://web.archive.org/web/20161204105956/http://www.toq... [25]

[6] [26] The essays appeared in The Occidental Quarterly, vol. 11, no. 1 (Spring 2011).

[7] [27] Greg Johnson, “The Boomerang Generation: Connecting with Our Proletariant,” Counter-Currents, August 23, 2013, https://www.counter-currents.com/2013/08/the-counter-curr... [28]

[8] [29] For a fuller account of Gamergate, see Vox Day’s SJWs Always Lie: Taking Down the Thought Police (Castalia House, 2015).

[9] [30] Gregory Hood, “For Others and their Prosperity,” Counter-Currents, May 2, 2014, https://www.counter-currents.com/2014/05/for-others-and-t... [31]

[10] [32] Jared Taylor, “Race Realism and the Alt Right,” Counter-Currents, October 25, 2016, https://www.counter-currents.com/2016/10/race-realism-and... [33]

[11] [34] Kevin MacDonald, “The Alt Right and the Jews,” Counter-Currents, September 13, 2016, https://www.counter-currents.com/2016/09/the-alt-right-an... [35]

[12] [36] George Hawley, Making Sense of the Alt-Right (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017), p. 68.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

L’Alt Right américaine est constituée d’une variété de groupes très différents les uns des autres. D’une part, nous avons des revues et des maisons d’édition qui ne se distinguent guère des nouvelles droites française ou germanophones, dans la mesure où elles entendent se poser comme des initiatives sérieuses et intellectuelles. D’autre part, nous avons des personnalités qui s’adonnent à la moquerie et à la satire. Citons, en ce domaine, le comique « RamZPaul » (photo), les séries de caricatures « Murdoch Murdoch ». L’humour que répandent ces initiatives-là est, bien sûr, politiquement incorrect, et de manière explicite ! Parfois, il est espiègle et seulement accessible aux « initiés ». Les tenants de gauche de la « religion civile » américaine y sont fustigés à qui mieux-mieux, sans la moindre pitié. Personne n’oserait un humour pareil sous nos latitudes européennes.

L’Alt Right américaine est constituée d’une variété de groupes très différents les uns des autres. D’une part, nous avons des revues et des maisons d’édition qui ne se distinguent guère des nouvelles droites française ou germanophones, dans la mesure où elles entendent se poser comme des initiatives sérieuses et intellectuelles. D’autre part, nous avons des personnalités qui s’adonnent à la moquerie et à la satire. Citons, en ce domaine, le comique « RamZPaul » (photo), les séries de caricatures « Murdoch Murdoch ». L’humour que répandent ces initiatives-là est, bien sûr, politiquement incorrect, et de manière explicite ! Parfois, il est espiègle et seulement accessible aux « initiés ». Les tenants de gauche de la « religion civile » américaine y sont fustigés à qui mieux-mieux, sans la moindre pitié. Personne n’oserait un humour pareil sous nos latitudes européennes. Het oude rechts heeft de slag om de samenleving verloren. Het is zo volledig door links verdreven dat tegenwoordig bijna iedereen, bewust of onbewust, meegaat in het linkse dogma van de gelijkheid. En dan meer en meer de gelijkheid van uitkomsten. Ieder verschil in macht en middelen wordt door de bien pensants als een ondraaglijk gevolg van onderdrukking gezien. En de grote boeman, de rechtgeaarde blanke man, heeft de plicht zijn “privileges” te onderkennen en zijn thuisland te delen met de onuitputtelijke stroom zielige bruine mensen van over de hele wereld. Zo doet hij boete voor de zondes en successen van zijn voorvaderen tot hij opgaat in de grote smeltkroes.

Het oude rechts heeft de slag om de samenleving verloren. Het is zo volledig door links verdreven dat tegenwoordig bijna iedereen, bewust of onbewust, meegaat in het linkse dogma van de gelijkheid. En dan meer en meer de gelijkheid van uitkomsten. Ieder verschil in macht en middelen wordt door de bien pensants als een ondraaglijk gevolg van onderdrukking gezien. En de grote boeman, de rechtgeaarde blanke man, heeft de plicht zijn “privileges” te onderkennen en zijn thuisland te delen met de onuitputtelijke stroom zielige bruine mensen van over de hele wereld. Zo doet hij boete voor de zondes en successen van zijn voorvaderen tot hij opgaat in de grote smeltkroes.