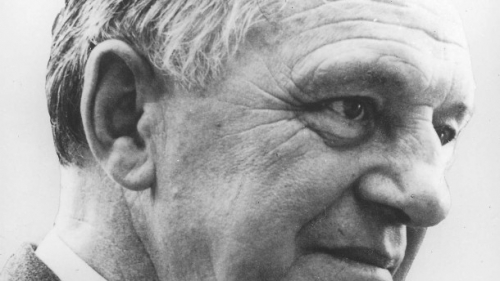

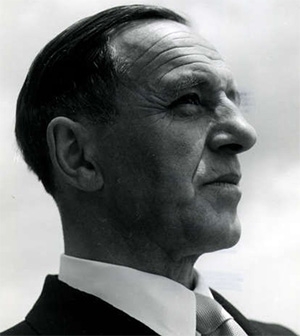

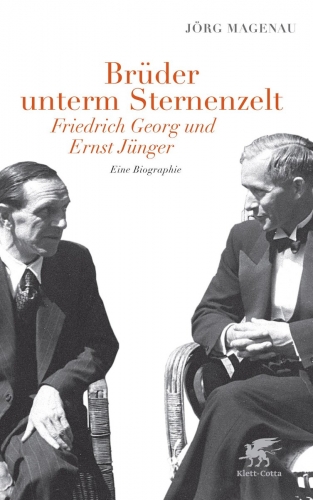

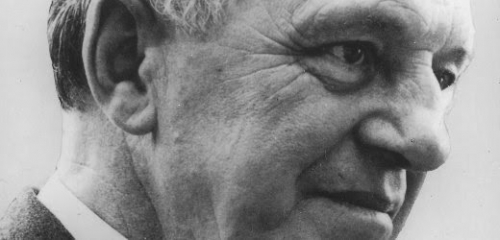

Nascido em 1 de setembro de 1989 em Hannover, irmão do famoso escritor alemão Ernst Jünger, Friedrich-Georg Jünger se interessou pela poesia desde uma idade muito jovem, despertando nele um forte interesse pelo classicismo alemão em um itinerário que atravessa Klopstock , Goethe e Hölderin. Graças a esta imersão precoce no trabalho de Hölderin, Friedrich-Georg Jünger é fascinado pela antiguidade clássica e percebe a essência da helenidade e da romanidade antigas como uma aproximação à natureza, como uma glorificação da elementalidade, ao mesmo tempo que é dotada de uma visão do homem que permanecerá imutável, sobrevivendo ao longo dos séculos na psique européia, às vezes visível à luz do dia, às vezes escondida. A era da técnica separou os homens dessa proximidade vivificante, elevando-o perigosamente acima do elemental. Toda a obra poética de Friedrich-Georg Jünger é um protesto veemente contra a pretensão mortífera que constitui esse distanciamento. Nosso autor permanecerá profundamente marcado pelas paisagens idílicas de sua infância, uma marca que se refletirá em seu amor incondicional pela Terra, pela flora e pela fauna (especialmente insetos: foi Friedrich-Georg quem apresentou seu irmão Ernst ao mundo da entomologia), pelos seres mais elementares da vida no planeta, pelas raízes culturais.

A Primeira Guerra Mundial acabará com essa imersão jovem na natureza. Friedrich-Georg se alistará em 1916 como aspirante a oficial. Severamente ferido no pulmão, na frente do Somme, em 1917, passa o resto do conflito em um hospital de campo. Depois de sua convalescença, se matricula em Direito, obtendo o título de doutor em 1924. Mas ele nunca seguirá a carreira de jurista, logo descobriu sua vocação como escritor político dentro do movimento nacionalista de esquerda, entre os nacional-revolucionários e o nacional-bolcheviques, unindo-se mais tarde à figura de Ernst Niekisch, editor da revista "Widerstand" (Resistência). A partir desta publicação, bem como de "Arminios" ou "Die Kommenden", os irmãos Jünger inauguraram um novo estilo que poderíamos definir como do "soldado nacionalista", expressado pelos jovens oficiais que chegaram recentemente do front e incapazes de se adaptar à vida civil . A experiência das trincheiras e o fragor dos ataques mostraram-lhes, através do suor e do sangue, que a vida não é um jogo inventado pelo cerebralismo, mas um rebuliço orgânico elemental onde, de fato, os instintos reinam. A política, em sua própria esfera, deve compreender a temperatura dessa agitação, ouvir essas pulsões, navegar em seus meandros para forjar uma força sempre jovem, nova e vivificante. Para Friedrich-Georg Jünger, a política deve ser apreendida de um ângulo cósmico, fora de todos os miasmas "burgueses, cerebrais e intelectualizantes". Paralelamente a esta tarefa de escritor político e profeta desse nacionalismo radicalmente anti-burguês, Friedrich-Georg Jünger mergulha na obra de Dostoiévski, Kant e dos grandes romancistas americanos. Junto com seu irmão Ernst, ele realiza uma série de viagens pelos países mediterrâneos: Dalmácia, Nápoles, Baleares, Sicília e as ilhas do Mar Egeu.

Quando Hitler sobe ao poder, o triunfante é um nacionalismo das massas, não aquele nacionalismo absoluto e cósmico que evocava a pequena falange (sic) "fortemente exaltada" que editou seus textos nas revistas nacional-revolucionárias. Em um poema, Der Mohn (A Papoula), Friedrich-Georg Jünger ironiza e descreve o nacional-socialismo como "a música infantil de uma embriaguez sem glória". Como resultado desses versículos sarcásticos, ele se vê envolto em uma série de problemas com a polícia, pelo que ele sai de Berlim e se instala, com Ernst, em Kirchhorst, na Baixa Saxônia.

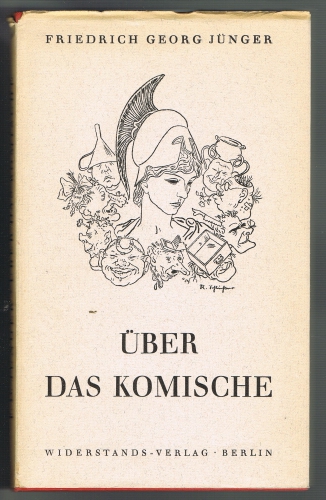

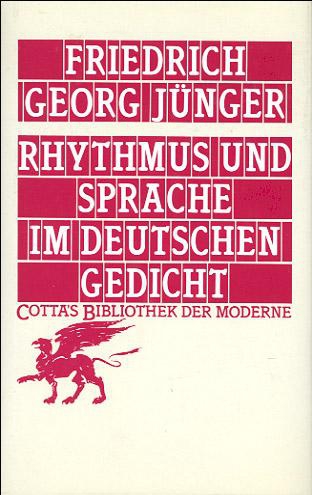

Aposentado da política depois de ter publicado mais de uma centena de poemas na revista de Niekisch - que vê pouco a pouco o aumento das pressões da autoridade até que finalmente é preso em 1937 -, Friedrich-Georg Jünger consagra por inteiro à criação literária, publicando em 1936 um ensaio intitulado Über das Komische e terminando em 1939 a primeira versão de seu maior trabalho filosófico: Die Perfektion der Technik (A Perfeição da Técnica). Os primeiros rascunhos deste trabalho foram destruídos em 1942, durante um bombardeio aliado. Em 1944, uma primeira edição, feita a partir de uma série de novos ensaios, é novamente reduzida às cinzas devido a um ataque aéreo. Finalmente, o livro aparece em 1946, provocando um debate em torno da problemática da técnica e da natureza, prefigurando, apesar de sua orientação "conservadora", todas as reivindicações ambientais alemãs dos anos 60, 70 e 80. Durante a guerra, Friedrich-Georg Jünger publicou poemas e textos sobre a Grécia antiga e seus deuses. Com o surgimento de Die Perfektion der Technik, que verá várias edições sucessivas, os interesses de Friedrich-Georg se voltam aos temas da técnica, da natureza, do cálculo, da mecanização, da massificação e da propriedade. Recusando, em Die Perfektion der Technik, enunciar suas teses sob um esquema clássico, linear e sistemático; seus argumentos aparecem "em espiral", de maneira desordenada, esclarecendo volta após volta, capítulo aqui, capítulo lá, tal ou qual aspecto da tecnificação global. Como filigrana, percebe-se uma crítica às teses que seu irmão Ernst mantinha então em Der Arbeiter (O Trabalhador), que aceitou como inevitável a evolução da técnica moderna. Sua posição antitécnica aborda a tese de Ortega y Gasset em Meditações sobre a Técnica (1939) de Henry Miller e de Lewis Munford (que usa o termo "megamaquinismo"). Em 1949, Friedrich-Georg Jünger publicou uma obra de exegese sobre Nietzsche, onde es interrogava sobre o sentido da teoria cíclica do tempo enunciado pelo anacoreta de Sils-Maria. Friedrich-Georg Jünger contesta a utilidade de usar e problematizar uma concepção cíclica dos tempos, porque este uso e esta problematização acabarão por conferir ao tempo uma forma única e intangível que, para Nietzsche, é concebida como cíclica. O tempo cíclico, próprio da Grécia das origens e do pensamento pré-cristão, deve ser percebido a partir dos ângulos do imaginário e não da teoria, que obriga a conjugar a naturalidade a partir de um modelo único de eternidade e, assim, o instante e o fato desaparecem sob os cortes arbitrários estabelecidos pelo tempo mecânico, segmentarizados em visões lineares. A temporalidade cíclica de Nietzsche, por seus cortes em ciclos idênticos e repetitivos, preserva, pensou Friedrich-Georg Jünger, algo de mecânico, de newtoniano, pelo que, finalmente, não é uma temporalidade "grega". O tempo, para Nietzsche, é um tempo policial, sequestrado; carece de apoio, de suporte (Tragend und Haltend). Friedrich-Georg Jünger canta uma a-temporalidade que é identificada com a natureza mais elementar, o "Wildnis", a natureza de Pã, o fundo natural intacto do mundo, não manchado pela mão humana, que é, em última instância, um acesso ao divino, ao último segredo do mundo. O "Wildnis" - um conceito fundamental no poeta "pagão" que é Friedrich-Georg Jünger - é a matriz de toda a vida, o receptáculo aonde deve retornar toda vida.

Em 1970, Friedrich-Georg Jünger fundou, juntamente com Max Llimmelheber, a revista trimestral "Scheidwege", onde figuraram na lista de colaboradores os principais representantes de um pensamento ao mesmo tempo naturalista e conservador, céticos em relação a todas as formas de planificação técnico. Entre os pensadores desta inclinação conservadora-ecológica que apresentaram suas teses na publicação podemos lembrar os nomes de Jürgen Dahl, Hans Seldmayr, Friederich Wagner, Adolf Portmann, Erwin Chargaff, Walter Heiteler, Wolfgang Häedecke, etc.

Friedrich-Georg Jünger morreu em Überlingen, perto das margens do lago de Constança, em 20 de julho de 1977.

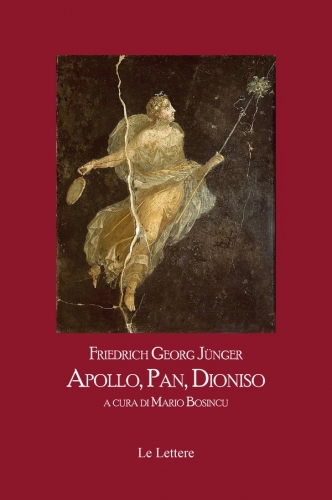

O germanista norte-americano Anton H. Richter, em seu trabalho sobre o pensamento de Friedrich-Georg Jünger, ressalta quatro temas essenciais em nosso autor: a antiguidade clássica, a essência cíclica da existência, a técnica e o poder de o irracional. Em seus escritos sobre antiguidade grega, Friedrich-Georg Jünger reflete sobre a dicotomia dionisíaca/titânica. Como dionisismo, abrange o apolíneo e o pânico, numa frente unida de forças organizacionais intactas contra as distorções, a fragmentação e a unidimensionalidade do titanismo e do mecanicismo de nossos tempos. A atenção de Friedrich-Georg Jünger centra-se essencialmente nos elementos ctônicos e orgânicos da antiguidade clássica. Desta perspectiva, os motivos recorrentes de seus poemas são a luz, o fogo e a água, forças elementares às quais ele homenageia profundamente. Friedrich-Georg Jünger zomba da razão calculadora, da sua ineficiência fundamental exaltando, em contraste, o poder do vinho, da exuberância do festivo, do sublime que se aninha na dança e nas forças carnavalescas. A verdadeira compreensão da realidade é alcançada pela intuição das forças, dos poderes da natureza, do ctônico, do biológico, do somático e do sangue, que são armas muito mais efetivas do que a razão, que o verbo plano e unidimensional, desmembrado, purgado, decapitado, despojado: de tudo o que torna o homem moderno um ser de esquemas incompletos. Apolo traz a ordem clara e a serenidade imutável; Dionísio traz as forças lúdicas do vinho e das frutas, entendidos como uma dádiva, um êxtase, uma embriaguez reveladora, mas nunca uma inconsciência; Pan, guardião da natureza, traz a fertilidade. Diante desses doadores generosos e desinteressados, os titãs são usurpadores, acumuladores de riqueza, guerreiros cruéis e antiéticos que enfrentam os deuses da profusão e da abundância que às vezes conseguem matá-los, lacerando seus corpos, devorando-os.

O germanista norte-americano Anton H. Richter, em seu trabalho sobre o pensamento de Friedrich-Georg Jünger, ressalta quatro temas essenciais em nosso autor: a antiguidade clássica, a essência cíclica da existência, a técnica e o poder de o irracional. Em seus escritos sobre antiguidade grega, Friedrich-Georg Jünger reflete sobre a dicotomia dionisíaca/titânica. Como dionisismo, abrange o apolíneo e o pânico, numa frente unida de forças organizacionais intactas contra as distorções, a fragmentação e a unidimensionalidade do titanismo e do mecanicismo de nossos tempos. A atenção de Friedrich-Georg Jünger centra-se essencialmente nos elementos ctônicos e orgânicos da antiguidade clássica. Desta perspectiva, os motivos recorrentes de seus poemas são a luz, o fogo e a água, forças elementares às quais ele homenageia profundamente. Friedrich-Georg Jünger zomba da razão calculadora, da sua ineficiência fundamental exaltando, em contraste, o poder do vinho, da exuberância do festivo, do sublime que se aninha na dança e nas forças carnavalescas. A verdadeira compreensão da realidade é alcançada pela intuição das forças, dos poderes da natureza, do ctônico, do biológico, do somático e do sangue, que são armas muito mais efetivas do que a razão, que o verbo plano e unidimensional, desmembrado, purgado, decapitado, despojado: de tudo o que torna o homem moderno um ser de esquemas incompletos. Apolo traz a ordem clara e a serenidade imutável; Dionísio traz as forças lúdicas do vinho e das frutas, entendidos como uma dádiva, um êxtase, uma embriaguez reveladora, mas nunca uma inconsciência; Pan, guardião da natureza, traz a fertilidade. Diante desses doadores generosos e desinteressados, os titãs são usurpadores, acumuladores de riqueza, guerreiros cruéis e antiéticos que enfrentam os deuses da profusão e da abundância que às vezes conseguem matá-los, lacerando seus corpos, devorando-os.

Pan é a figura central do panteão pessoal de Friedrich-Georg Jünger; Pan é o governante da "Wildnis", da natureza primordial que os titãs desejam arrasar. Friedrich-Georg Jünger se remete a Empédocles, que ensinava que ele forma um "contiuum epistemológico" com a natureza: toda a natureza está no homem e pode ser descoberta através do amor.

Simbolizado por rios e cobras, o princípio da recorrência, do retorno incessante, pelo qual todas as coisas alcançam a "Wildnis" original, é também o caminho para retornar a esse mesmo Wildnis. Friedrich-Georg Jünger canta o tempo cíclico, diferente do tempo linear-unidirecional judaico-cristão, segmentado em momentos únicos, irrepetíveeis, sobre um caminho também único que leva à Redenção. O homem moderno ocidental, alérgico aos esconderijos imponderáveis onde a "Wildnis" se manifesta, optou pelo tempo contínuo e vetorial, tornando assim a sua existência um segmento entre duas eternidades atemporais (o antes do nascer e o depois da morte). Aqui se enfrentam dois tipos humanos: o homem moderno, impregnado com a visão judaico-cristã e linear do tempo, e o homem orgânico, que se reconhece inextricavelmente ligado ao cosmos e aos ritmos cósmicos.

A Perfeição da Técnica

Denúncia do titanismo mecanicista ocidental, este trabalho é a pedreira onde todos os pensadores ecológicos contemporâneos se nutriram para afinar suas críticas. Dividida em duas grandes partes e uma digressão, composta por uma multiplicidade de pequenos capítulos concisos, a obra começa com uma observação fundamental: a literatura utópica, responsável pela introdução do idealismo técnico no campo político, só provocou um desencanto da própria veia utópica. A técnica não resolve nenhum problema existencial do homem, não aumenta o gozo do tempo, não reduz o trabalho: ela tão somente desloca o manual em proveito do "organizativo". A técnica não cria novas riquezas; pelo contrário: condena a classe trabalhadora ao pauperismo físico e moral permanente. O desdobramento desenfreado da técnica é causado por uma falta geral da condição humana que a razão se esforça para sanar. Mas essa falta não desaparece com a invasão da técnica, que não é senão uma camuflagem grosseira, um remendo triste. A máquina é devoradora, aniquiladora da "substância": sua racionalidade é pura ilusão. O economista acredita, a partir de sua apreensão particular da realidade, que a técnica é uma fonte de riquezas, mas não parece observar que sua racionalidade quantitativista não é senão aparência pura e simples, que a técnica, em sua vontade de ser aperfeiçoada até o infinito, não segue senão sua própria lógica, uma lógica que não é econômica.

Uma das características do mundo moderno é o conflito tático entre o economista e o técnico: o último aspira a determinar processos de produção a favor da lucratividade, um fator que é puramente subjetivo. A técnica, quando atinge seu grau mais alto, leva a uma economia disfuncional. Essa oposição entre técnica e economia pode produzir estupor em mais de um crítico da unidimensionalidade contemporânea, acostumada a colocar hipertrofias técnicas e econômicas na mesma caixa de alfaiate. Mas Friedrich-Georg Jünger concebe a economia a partir de sua definição etimológica: como medida e norma dos "oikos", da habitação humana, bem circunscrita no tempo e no espaço. A forma atual adotada pelos "oikos" vem de uma mobilização exagerada dos recursos, assimilável à economia da pilhagem e da rapina (Raubbau), de uma concepção mesquinha do lugar que se ocupa sobre a Terra, sem consideração pelas gerações passadas e futuras.

A idéia central de Friedrich-Georg Jünger sobre a técnica é a de um automatismo dominado por sua própria lógica. A partir do momento em que essa lógica se põe em marcha, ela escapa aos seus criadores. O automatismo da técnica, então, se multiplica em função exponencial: as máquinas, por si só, impõem a criação de outras máquinas, até atingir o automatismo completo, mecanizado e dinâmico, em um tempo segmentado, um tempo que não é senão um tempo morto. Este tempo morto penetra no tecido orgânico do ser humano e sujeita o homem à sua lógica letal particular. O homem é, portanto, despojado do "seu" tempo interno e biológico, mergulhado em uma adaptação ao tempo inorgânico e morto da máquina. A vida é então imersa em um grande automatismo governado pela soberania absoluta da técnica, convertida senhora e dona de seus ciclos e ritmos, de sua percepção de si e do mundo exterior. O automatismo generalizado é "a perfeição da técnica", à qual Friedrich-Georg, um pensador organicista, opõe a "maturação" (die Reife) que só pode ser alcançada por seres naturais, sem coerção ou violência. A principal característica da gigantesca organização titânica da técnica, dominante na era contemporânea, é a dominação exclusiva exercida por determinações e deduções causais, características da mentalidade e da lógica técnica. O Estado, como entidade política, pode adquirir, pelo caminho da técnica, um poder ilimitado. Mas isso não é, para o Estado, senão uma espécie de pacto com o diabo, porque os princípios inerentes à técnica acabarão por remover sua substância orgânica, substituindo-a por puro e rígido automatismo técnico.

Quem diz automatização total diz organização total, no sentido de gestão. O trabalho, na era da multiplicação exponencial de autômatos, é organizado para a perfeição, isto é, para a rentabilidade total e imediata, deixando de lado ou sem considerar a mão-de-obra ou o útil. A técnica só é capaz de avaliar a si mesma, o que implica uma automação a todo custo, o que, por sua vez, implica troca a todo custo, o que leva à normalização a todo custo, cuja conseqüência é a padronização a todo custo. Friedrich-Georg Jünger acrescenta o conceito de "partição" (Stückelung), onde "partes" não são mais "partes", mas "peças" (Stücke), reduzidas a uma função de mero aparato, uma função inorgânica.

Friedrich-Georg Jünger cita Marx para denunciar a alienação desse processo, mas se distancia dele ao ver que este considera o processo técnico como um "fatum" necessário no processo de emancipação da classe proletária. O trabalhador (Arbeiter) é precisamente "trabalhador" porque está conectado, "volens nolens", ao aparato de produção técnica. A condição proletária não depende da modéstia econômica ou do rendimento, mas dessa conexão, independentemente do salário recebido. Esta conexão despersonaliza e faz desaparecer a condição de pessoa. O trabalhador é aquele que perdeu o benefício interno que o ligava à sua atividade, um benefício que evitava sua intercambiabilidade. A alienação não é um problema induzido pela economia, como Marx pensou, mas pela técnica. A progressão geral do automatismo desvaloriza todo o trabalho que possa ser interno e espontâneo no trabalhador, ao mesmo tempo que favorece inevitavelmente o processo de destruição da natureza, o processo de "devoração" (Verzehr) dos substratos (dos recursos oferecidos pela Mãe-Natureza, generosa e esbanjadora "donatrix"). Por causa dessa alienação técnica, o trabalhador é precipitado em um mundo de exploração onde ele não possui proteção. Para beneficiar-se de uma aparência de proteção, ela deve criar organizações - sindicatos - mas com o erro de que essas organizações também estejam conectadas ao aparato técnico. A organização protetora não emancipa, enjaula. O trabalhador se defende contra a alienação e a sua transformação em peça, mas, paradoxalmente, aceita o sistema de automação total. Marx, Engels e os primeiros socialistas perceberam a alienação econômica e política, mas eram cegos para a alienação técnica, incapazes de compreender o poder destrutivo da máquina. A dialética marxista, de fato, se torna um mecanicismo estéril ao serviço de um socialismo maquinista. O socialista permanece na mesma lógica que governa a automação total sob a égide do capitalismo. Mas o pior é que o seu triunfo não terminará (a menos que abandone o marxismo) com a alienação automatista, mas será um dos fatores do movimento de aceleração, simplificação e crescimento técnico. A criação de organizações é a causa da gênese da mobilização total, que transforma tudo em celulares e em todos os lugares em oficinas ou laboratórios cheios de agitação incessante e zumbidos. Toda área social que tende a aceitar essa mobilização total favorece, queira ou não, a repressão: é a porta aberta para campos de concentração, aglomerações, deportações em massa e massacres em massa. É o reinado do gestor impávido, uma figura sinistra que pode aparecer sob mil máscaras. A técnica nunca produz harmonia, a máquina não é uma deusa dispensadora de bondades. Pelo contrário, esteriliza os substratos naturais doados, organiza a pilhagem planejada contra a "Wildnis". A máquina é devoradora e antropófaga, deve ser alimentada sem cessar e, uma vez que acumula mais do que doa, acabará um dia com todas as riquezas da Terra. As enormes forças naturais elementares são desenraizadas pela gigantesca maquinaria e retém os prisioneiros por ela e nela, o que não conduz senão a catástrofes explosivas e à necessidade de uma sobrevivência constante: outra faceta da mobilização total.

As massas se entrelaçam voluntariamente nesta automação total, ao mesmo tempo que anulam as resistências isoladas de indivíduos conscientes. As massas são levadas pelo rápido movimento da automação, a tal ponto que, em caso de quebra ou paralisação momentânea do movimento linear para a automação, elas experimentam uma sensação de vida que acham insuportável.

A guerra, também, a partir de agora, será totalmente mecanizada. Os potenciais de destruição são amplificados ao extremo. A reivindicação de uniformes, o valor mobilizador dos símbolos, a glória, desaparecem na perfeição técnica. A guerra só pode ser suportada por soldados tremendamente endurecidos e tenazes, apenas os homens que possam exterminar a piedade em seus corações poderão suportá-la.

A mobilidade absoluta que inaugura a automação total se volta contra tudo tudo que pode significar duração e estabilidade, especificamente contra a propriedade (Eigentum). Friedrich-Georg Jünger, ao meditar sobre essa afirmação, define a propriedade de uma maneira original e particular. A existência de máquinas depende de uma concepção exclusivamente temporal, a existência da propriedade é devida a uma concepção espacial. A propriedade implica limites, definições, cercas, paredes e paredes, "clausuras" em suma. A eliminação dessas delimitações é uma razão de ser para o coletivismo técnico. A propriedade é sinônimo de um campo de ação limitado, circunscrito, fechado em um espaço específico e preciso. Para progredir de forma vetorial, a automação precisa pular os bloqueios da propriedade, um obstáculo para a instalação de seus onipresentes meios de controle, comunicação e conexão. Uma humanidade privada de todas as formas de propriedade não pode escapar da conexão total. O socialismo, na medida em que nega a propriedade, na medida em que rejeita o mundo das "zonas enclausuradas", facilita precisamente a conexão absoluta, que é sinônimo de manipulação absoluta. Segue-se que o proprietário de máquinas não é proprietário; o capitalismo mecanicista mina a ordem das propriedades, caracterizada por duração e estabilidade, em preferência de um dinamismo omnidisolvente. A independência da pessoa é uma impossibilidade nessa conexão aos fatos e ao modo de pensar próprio do instrumentalismo e do organizacionismo técnicos.

A mobilidade absoluta que inaugura a automação total se volta contra tudo tudo que pode significar duração e estabilidade, especificamente contra a propriedade (Eigentum). Friedrich-Georg Jünger, ao meditar sobre essa afirmação, define a propriedade de uma maneira original e particular. A existência de máquinas depende de uma concepção exclusivamente temporal, a existência da propriedade é devida a uma concepção espacial. A propriedade implica limites, definições, cercas, paredes e paredes, "clausuras" em suma. A eliminação dessas delimitações é uma razão de ser para o coletivismo técnico. A propriedade é sinônimo de um campo de ação limitado, circunscrito, fechado em um espaço específico e preciso. Para progredir de forma vetorial, a automação precisa pular os bloqueios da propriedade, um obstáculo para a instalação de seus onipresentes meios de controle, comunicação e conexão. Uma humanidade privada de todas as formas de propriedade não pode escapar da conexão total. O socialismo, na medida em que nega a propriedade, na medida em que rejeita o mundo das "zonas enclausuradas", facilita precisamente a conexão absoluta, que é sinônimo de manipulação absoluta. Segue-se que o proprietário de máquinas não é proprietário; o capitalismo mecanicista mina a ordem das propriedades, caracterizada por duração e estabilidade, em preferência de um dinamismo omnidisolvente. A independência da pessoa é uma impossibilidade nessa conexão aos fatos e ao modo de pensar próprio do instrumentalismo e do organizacionismo técnicos.

Entre suas reflexões críticas sobre a automatização e a tecnificação totais nos tempos modernos, Friedrich-Georg Jünger apela aos grandes filósofos da tradição europeia. Descartes inaugura um idealismo que estabelece uma separação insuperável entre o corpo e o espírito, eliminando o "sistema de influências psíquicas" que interligava ambos, para eventualmente substituí-lo por uma intervenção divina pontual que faz de Deus um simples demiurgo-relojoeiro. A "res extensa" de Descartes em um conjunto de coisas mortas, explicável como um conjunto de mecanismos em que o homem, instrumento do Deus-relojoeiro, pode intervir completamente impune em todos os momentos. A "res cogitans" é instituído como mestre absoluto dos processos mecânicos que governam o Universo. O homem pode se tornar um deus: um grande relojoeiro que pode manipular todas as coisas ao seu gosto e alvedrio, sem cuidado ou respeito. O cartesianismo dá o sinal de saída da exploração tecnicista ao extremo da Terra.

O germanista norte-americano Anton H. Richter, em seu trabalho sobre o pensamento de Friedrich-Georg Jünger, ressalta quatro temas essenciais em nosso autor: a antiguidade clássica, a essência cíclica da existência, a técnica e o poder de o irracional. Em seus escritos sobre antiguidade grega, Friedrich-Georg Jünger reflete sobre a dicotomia dionisíaca/titânica. Como dionisismo, abrange o apolíneo e o pânico, numa frente unida de forças organizacionais intactas contra as distorções, a fragmentação e a unidimensionalidade do titanismo e do mecanicismo de nossos tempos. A atenção de Friedrich-Georg Jünger centra-se essencialmente nos elementos ctônicos e orgânicos da antiguidade clássica. Desta perspectiva, os motivos recorrentes de seus poemas são a luz, o fogo e a água, forças elementares às quais ele homenageia profundamente. Friedrich-Georg Jünger zomba da razão calculadora, da sua ineficiência fundamental exaltando, em contraste, o poder do vinho, da exuberância do festivo, do sublime que se aninha na dança e nas forças carnavalescas. A verdadeira compreensão da realidade é alcançada pela intuição das forças, dos poderes da natureza, do ctônico, do biológico, do somático e do sangue, que são armas muito mais efetivas do que a razão, que o verbo plano e unidimensional, desmembrado, purgado, decapitado, despojado: de tudo o que torna o homem moderno um ser de esquemas incompletos. Apolo traz a ordem clara e a serenidade imutável; Dionísio traz as forças lúdicas do vinho e das frutas, entendidos como uma dádiva, um êxtase, uma embriaguez reveladora, mas nunca uma inconsciência; Pan, guardião da natureza, traz a fertilidade. Diante desses doadores generosos e desinteressados, os titãs são usurpadores, acumuladores de riqueza, guerreiros cruéis e antiéticos que enfrentam os deuses da profusão e da abundância que às vezes conseguem matá-los, lacerando seus corpos, devorando-os.

O germanista norte-americano Anton H. Richter, em seu trabalho sobre o pensamento de Friedrich-Georg Jünger, ressalta quatro temas essenciais em nosso autor: a antiguidade clássica, a essência cíclica da existência, a técnica e o poder de o irracional. Em seus escritos sobre antiguidade grega, Friedrich-Georg Jünger reflete sobre a dicotomia dionisíaca/titânica. Como dionisismo, abrange o apolíneo e o pânico, numa frente unida de forças organizacionais intactas contra as distorções, a fragmentação e a unidimensionalidade do titanismo e do mecanicismo de nossos tempos. A atenção de Friedrich-Georg Jünger centra-se essencialmente nos elementos ctônicos e orgânicos da antiguidade clássica. Desta perspectiva, os motivos recorrentes de seus poemas são a luz, o fogo e a água, forças elementares às quais ele homenageia profundamente. Friedrich-Georg Jünger zomba da razão calculadora, da sua ineficiência fundamental exaltando, em contraste, o poder do vinho, da exuberância do festivo, do sublime que se aninha na dança e nas forças carnavalescas. A verdadeira compreensão da realidade é alcançada pela intuição das forças, dos poderes da natureza, do ctônico, do biológico, do somático e do sangue, que são armas muito mais efetivas do que a razão, que o verbo plano e unidimensional, desmembrado, purgado, decapitado, despojado: de tudo o que torna o homem moderno um ser de esquemas incompletos. Apolo traz a ordem clara e a serenidade imutável; Dionísio traz as forças lúdicas do vinho e das frutas, entendidos como uma dádiva, um êxtase, uma embriaguez reveladora, mas nunca uma inconsciência; Pan, guardião da natureza, traz a fertilidade. Diante desses doadores generosos e desinteressados, os titãs são usurpadores, acumuladores de riqueza, guerreiros cruéis e antiéticos que enfrentam os deuses da profusão e da abundância que às vezes conseguem matá-los, lacerando seus corpos, devorando-os.

A mobilidade absoluta que inaugura a automação total se volta contra tudo tudo que pode significar duração e estabilidade, especificamente contra a propriedade (Eigentum). Friedrich-Georg Jünger, ao meditar sobre essa afirmação, define a propriedade de uma maneira original e particular. A existência de máquinas depende de uma concepção exclusivamente temporal, a existência da propriedade é devida a uma concepção espacial. A propriedade implica limites, definições, cercas, paredes e paredes, "clausuras" em suma. A eliminação dessas delimitações é uma razão de ser para o coletivismo técnico. A propriedade é sinônimo de um campo de ação limitado, circunscrito, fechado em um espaço específico e preciso. Para progredir de forma vetorial, a automação precisa pular os bloqueios da propriedade, um obstáculo para a instalação de seus onipresentes meios de controle, comunicação e conexão. Uma humanidade privada de todas as formas de propriedade não pode escapar da conexão total. O socialismo, na medida em que nega a propriedade, na medida em que rejeita o mundo das "zonas enclausuradas", facilita precisamente a conexão absoluta, que é sinônimo de manipulação absoluta. Segue-se que o proprietário de máquinas não é proprietário; o capitalismo mecanicista mina a ordem das propriedades, caracterizada por duração e estabilidade, em preferência de um dinamismo omnidisolvente. A independência da pessoa é uma impossibilidade nessa conexão aos fatos e ao modo de pensar próprio do instrumentalismo e do organizacionismo técnicos.

A mobilidade absoluta que inaugura a automação total se volta contra tudo tudo que pode significar duração e estabilidade, especificamente contra a propriedade (Eigentum). Friedrich-Georg Jünger, ao meditar sobre essa afirmação, define a propriedade de uma maneira original e particular. A existência de máquinas depende de uma concepção exclusivamente temporal, a existência da propriedade é devida a uma concepção espacial. A propriedade implica limites, definições, cercas, paredes e paredes, "clausuras" em suma. A eliminação dessas delimitações é uma razão de ser para o coletivismo técnico. A propriedade é sinônimo de um campo de ação limitado, circunscrito, fechado em um espaço específico e preciso. Para progredir de forma vetorial, a automação precisa pular os bloqueios da propriedade, um obstáculo para a instalação de seus onipresentes meios de controle, comunicação e conexão. Uma humanidade privada de todas as formas de propriedade não pode escapar da conexão total. O socialismo, na medida em que nega a propriedade, na medida em que rejeita o mundo das "zonas enclausuradas", facilita precisamente a conexão absoluta, que é sinônimo de manipulação absoluta. Segue-se que o proprietário de máquinas não é proprietário; o capitalismo mecanicista mina a ordem das propriedades, caracterizada por duração e estabilidade, em preferência de um dinamismo omnidisolvente. A independência da pessoa é uma impossibilidade nessa conexão aos fatos e ao modo de pensar próprio do instrumentalismo e do organizacionismo técnicos.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les éditions Allia publient cette semaine un essai de Friedrich-Georg Jünger intitulé La perfection de la technique. Frère d'Ernst Jünger. Auteur de très nombreux ouvrages, Friedrich-Georg Jünger a suivi une trajectoire politique et intellectuelle parallèle à celle de son frère Ernst et a tout au long de sa vie noué un dialogue fécond avec ce dernier. Parmi ses oeuvres ont été traduits en France un texte écrit avec son frère, datant de sa période conservatrice révolutionnaire,

Les éditions Allia publient cette semaine un essai de Friedrich-Georg Jünger intitulé La perfection de la technique. Frère d'Ernst Jünger. Auteur de très nombreux ouvrages, Friedrich-Georg Jünger a suivi une trajectoire politique et intellectuelle parallèle à celle de son frère Ernst et a tout au long de sa vie noué un dialogue fécond avec ce dernier. Parmi ses oeuvres ont été traduits en France un texte écrit avec son frère, datant de sa période conservatrice révolutionnaire,