jeudi, 08 septembre 2022

De Macron à Mitterrand : remarques sur la dictature pérenne du parti socialiste en France

De Macron à Mitterrand : remarques sur la dictature pérenne du parti socialiste en France

Nicolas Bonnal

Quelques analystes de papier-mâché vantaient la disparition du parti socialiste en France. En réalité il est puissant comme jamais, en France, en Allemagne ou en Amérique. Car le parti socialiste ou la social-démocratie est le parti de la Fin des Temps, le parti de l’Etat omniprésent et forcené, et de la guerre éternelle (pour Rothbard et les libertariens américains). Le PS en France comme la SPD en Allemagne ou le parti démocrate en Amérique constituent aussi l’armature de l’Etat profond de ces malheureux pays et il semble qu’ils agissent comme une tunique de Nessus dont on ne puisse jamais se débarrasser. C’est que la masse des cancres vote pour eux et que la droite crève (rêve).

Il y a quelques mois l’excellent et bon communiste Régis de Castelnau écrivait : "La campagne de l’élection présidentielle 2022 est un grand révélateur de la déshérence politique dans laquelle se trouve notre pays. En 2017, un trio constitué de la haute fonction publique d’État, de l’oligarchie économique et de la magistrature politisée, a organisé de longue main un coup d’État pour faire élire à la magistrature suprême un parfait inconnu. S’appuyant sur l’essentiel de l’armature politique du Parti socialiste, Emmanuel Macron a ainsi réalisé un hold-up mettant la dernière main à la destruction des institutions républicaines."

J’avais un grand-oncle jadis, inévitable retraité de la fonction publique, qui me disait voter socialiste car c’était le parti fourre-tout. De fait ça l’est.

Le PS est le parti de la ponction publique et des retraités.

C’est le parti des boomers et des octogénaires ludiques façon Cohn-Bendit.

C’est le parti des affairistes et des magouilleurs (relisez les Montaldo)

C’est le parti des écolos, des antiracistes et des féministes, le parti du sociétal déstructurant.

C’est le parti de l’américanisation à mort.

C’est le parti bourgeois héritier de la bohême et de la Terreur révolutionnaire.

C’est le parti de la conspiration et de l’occultisme (Muray en a bien parlé dans son Dix-neuvième et moi dans mon Mitterrand).

Le PS est aussi le parti de la désindustrialisation. On avait un déficit commercial de cent milliards en 1982 ; aujourd’hui on est à 150 milliards de francs mensuels.

Enfin c’est le parti des envahisseurs. 92% des musulmans ont voté pour Hollande en 2012, Hollande qui a sonné le glas de la France.

Le PS contrôle l’Elysée avec Macron et ses acolytes du business, et aussi l’opposition avec l’ineffable Mélenchon, monsieur antiracisme des années 80. Il contrôle aussi la républicaine fille Le Pen (la Marine, je lui dis merde comme Escartefigue, moi qui ai une carte du père me demandant d’être candidat) et ce troupeau d’assistés républicains dont Tocqueville a si brillamment parlé :

« Au-dessus de ceux-là s'élève un pouvoir immense et tutélaire, qui se charge seul d'assurer leur jouissance et de veiller sur leur sort. Il est absolu, détaillé, régulier, prévoyant et doux. Il ressemblerait à la puissance paternelle si, comme elle, il avait pour objet de préparer les hommes à l'âge viril; mais il ne cherche, au contraire, qu'à les fixer irrévocablement dans l'enfance; il aime que les citoyens se réjouissent, pourvu qu'ils ne songent qu'à se réjouir. Il travaille volontiers à leur bonheur; mais il veut en être l'unique agent et le seul arbitre; il pourvoit à leur sécurité, prévoit et assure leurs besoins, facilite leurs plaisirs, conduit leurs principales affaires, dirige leur industrie, règle leurs successions, divise leurs héritages; que ne peut-il leur ôter entièrement le trouble de penser et la peine de vivre? »

Le reste est toujours d’actualité, sauf que le troupeau n’est plus du tout industrieux comme on sait :

« Après avoir pris ainsi tour à tour dans ses puissantes mains chaque individu, et l'avoir pétri à sa guise, le souverain étend ses bras sur la société tout entière; il en couvre la surface d'un réseau de petites règles compliquées, minutieuses et uniformes, à travers lesquelles les esprits les plus originaux et les âmes les plus vigoureuses ne sauraient se faire jour pour dépasser la foule; il ne brise pas les volontés, mais il les amollit, les plie et les dirige; il force rarement d'agir, mais il s'oppose sans cesse à ce qu'on agisse; il ne détruit point, il empêche de naître; il ne tyrannise point, il gêne, il comprime, il énerve, il éteint, il hébète, et il réduit enfin chaque nation à n'être plus qu'un troupeau d'animaux timides et industrieux, dont le gouvernement est le berger. »

Que le berger gouvernemental du reste, sur ordre de Fink, de Blinken, d’Harari et de Klaus Schwab mène son troupeau à l’abattoir, ce n’est plus moi qui m’y opposerai. Marre d’être traité de facho pour exiger du chauffage en hiver ; pas assez PS pour ça.

Comme disait Vigny : « vous ne recevrez pas un cri d’amour de moi ».

Sources:

https://www.amazon.fr/gp/product/B0B7QLGBZ8/ref=dbs_a_def...

https://www.amazon.fr/Mitterrand-grand-initi%C3%A9-Nicola...

https://www.vududroit.com/2022/09/jean-luc-melenchon-en-m...

23:55 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : france, parti socialiste, europe, affaires européennes, emmanuel macron, françois mitterrand |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 17 juin 2022

De la génération Mitterrand au peuple nouveau de Macron

De la génération Mitterrand au peuple nouveau de Macron

Nicolas Bonnal

Le peuple nouveau n’a pas fini de nous étonner avec son crétinisme électoral : il est de gauche ou d’extrême-gauche bien tempérée, écolo, russophobe, américanisé jusqu’à l’os, pleurnichard humanitaire. Il est super ce peuple. Et il est prêt à vivre sans rire de l’éolienne et de la bicyclette (pour repousser Poutine et la Chine avec Biden ?) avant de se coller antenne et puce dans son cerveau branché.

La droite BCBG et attardée est bien attrapée et découvre que le peuple nouveau dont a parlé Macron donc ne veut plus d’elle : ce peuple nouveau veut du Reset de la pénurie écologiquement programmée ; ce peuple nouveau, abstentionniste ou pas, veut terminer le grand remplacement ; le peuple nouveau adore la dictature sanitaire (vite le vaccin obligatoire) et il veut de la tyrannie bureaucratique de Bruxelles et de la guerre éternelle US contre la Russie, condition du maintien de la caste au pouvoir (comme le rappelle Orwell) ; le peuple nouveau woke, féministe (Chesterton annonçait que sous le règne de l’ogresse américaine nous ne serions plus des citoyens mais des enfants) et humanitaire a même remplacé le vieux peuple de droite sur la côte d’azur, comme vient de s’en rendre compte l’infortuné Zemmour qui aurait dû se contenter de rédiger des brochures touristiques, seule destination légitime des amateurs d’histoire aujourd’hui ; car le reste est bon pour la culture de l’annulation. Je dis cela sans animosité car j’ai plus retenu enfant de mes lectures du guide vert Michelin que de mes manuels Malet-Isaac.

Mais j’ai parlé de Mitterrand et de sa génération. C’est bien lui l’oncle de Mélenchon et le grand-père de Macron. Il me semble que son ombre s’est étalée partout, que son bras s’est allongé, comme dit Gandalf. Et j’ai expliqué pourquoi jadis : Mitterrand avait fondé une religion New Age et rétrofuturiste bien plus efficace que toutes les autres réunies. Mélenchon incarne la génération Mitterrand, la génération des potes et du trotskisme, de SOS Racisme et du mondialisme ; mais Macron aussi, qui incarne le mariage de la gauche caviar et du mondialisme américano-bruxellois. Sous Mitterrand, après le départ des communistes qui avaient énervé plus qu’effrayé les bourgeois, ce petit monde s’est entendu. Et le peuple petit-bourgeois bohême a pris de la graine.

Mitterrand est le père du PS, le parti attrape-tout, qui s’est toujours très bien entendu avec les milliardaires (la fortune de Bernard Arnault a été multipliée par cent en quarante ans) qui ont frayé depuis cette époque bénie avec les hauts fonctionnaires mondialisés et désireux de ne plus se contenter de miettes : ils bradent le patrimoine national et empochent la commission. Cela n’a pas empêché le bon peuple de voter et de rester socialo et mitterrandien : il est bien passé des ténèbres à la lumière.

Sources :

https://www.amazon.fr/Mitterrand-grand-initi%C3%A9-Nicola...

https://www.amazon.fr/DANS-GUEULE-BETE-LAPOCALYPSE-MONDIA...

16:54 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, europe, affaires européennes, france, françois mitterrand, emmanuel macron, nicolas bonnal |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 27 avril 2019

Macron et le couronnement de la génération Mitterrand

Macron et le couronnement de la génération Mitterrand

Les Carnets de Nicolas Bonnal

Ex: http://www.dedefensa.org

Certains s’énervent après Macron, il n’y a pas de quoi. De toute manière si le système le remplace, on aura pire après (c’est le syndrome de Denys de Syracuse, étudié ici). Personne ne veut de révolution parce que tout le monde a de quoi bouffer, cliquer et regarder la télé. Le système c’est nous, c’est tout.

Désolé, mais Macron ce n’est que la continuation de la génération Mitterrand. C’est du présent perpétuel sur trente ans, pas celui sur 200 que j’ai l’habitude de commenter ici, à coups de Nietzsche et de Dostoïevski, de Poe ou de Baudelaire. Autoritarisme (coup d’Etat permanent), haine du peuple et des pauvres, américanisme, inféodation à l’Allemagne, aux richissimes, monarchie culturelle, tout est déjà chez Mitterrand deuxième mouture, chez qui Macron aura puisé son inspiration, y compris en recyclant les cathos zombies et les larves bureaucratiques de la droite folle ou molle. Alors un rappel…

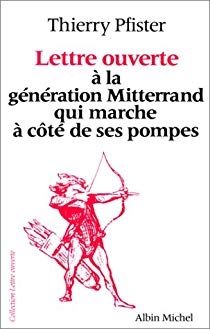

Thierry Pfister fut mon éditeur chez Albin Michel et me publia la deuxième version du Mitterrand grand initié. Ce grand professionnel était un gentilhomme et un homme de gauche convaincu qui avait rompu avec le mitterrandisme deuxième mouture des années 84-85 qui dégénérait alors en « tonton mania ». En 1989 il publia sa splendide lettre à la génération Mitterrand qui vendit 300 000 exemplaires. Les années 90 marquèrent l’agonie du mitterrandisme revenu depuis à la mode dans ce pays sans mémoire et sans histoire.

Thierry Pfister fut mon éditeur chez Albin Michel et me publia la deuxième version du Mitterrand grand initié. Ce grand professionnel était un gentilhomme et un homme de gauche convaincu qui avait rompu avec le mitterrandisme deuxième mouture des années 84-85 qui dégénérait alors en « tonton mania ». En 1989 il publia sa splendide lettre à la génération Mitterrand qui vendit 300 000 exemplaires. Les années 90 marquèrent l’agonie du mitterrandisme revenu depuis à la mode dans ce pays sans mémoire et sans histoire.

Florilège (je n’ai pas le PDF et ma secrétaire est en vacances !) :

Sur les intellectuels juifs qui en énervent tant aujourd’hui (et qui énervaient déjà Adorno en personne), Thierry Pfister rappelle « une plaisanterie en yiddish qui fit rire tous les leaders de mai 68 ». Et d’ajouter que « Mai 68 fut pour un leader juif une révolution juive, un écho millénaire du messianisme hébraïque (p.39-40). » ;

SOS racisme ? « Une association de défense de beurs peuplée de sionistes ravis d’avoir trouvé plus métèques qu’eux (p.71)… »

Europe allemande ? Pfister ajoute que déjà « la France se soumet de bonne grâce aux règles de la zone deutschemark où elle fait désormais figure de première sous-traitante. »

Manipulation historique ? Sur la débilité des experts d’alors, il rappelle que « dénoncer l’horreur nazie ne justifie pas le dangereux matraquage d’approximations… (p.43) ».

Amusant : Pfister explique que le PS se situe à l’extrême droite de l’internationale socialiste et souligne que le FN fait grossièrement partie du système… En bref, Mitterrand avant Macron célèbre le « conformisme étatique et social » de cette France pas très réformatrice.

Triomphe du communautarisme et fin d’un modèle ? « La civilisation US est celle du ghetto ; à chacun son quartier, à chacun sa piscine… »

On parle de Macron et des riches. On oublie Mitterrand et l’Oréal, Mitterrand et Bettencourt, Mitterrand qui fabriqua avec le crédit lyonnais les ultra-riches actuels comme Arnault et Pinault. Pfister écrit déjà « qu’on a une fiscalité qui touche les cadres possesseurs de leur appartement mais épargne les dynasties qui se transmettent des collections d’objets d’art comme ceux qui se dissimulent derrière la notion floue d’outil de travail… (p.94). » Et comme on n’aime pas le peuple qui vous porta au pouvoir en 1981, « les socialistes se déchargent sur d’anciens ministres de droite du soin de négocier avec les syndicats (p.96). »

Abrutissement et aggiornamento ? La télévision se limite à « la promotion des disques, des magazines et des myopathes », et les brillants oligarques de la gauche sociétale demandent à la gauche de « rompre avec le corpus poussiéreux qui la tenait prisonnière du siècle précédent (Kouchner, Karmitz, Lévy, Minc, p.111). » Pfister ajoute que « les élites vont au peuple comme les dames patronnesses vont au peuple. » Il remarque au cours d’un voyage en Bourgogne qu’un « haut fonctionnaire de la culture parle d’indigène, de typique en regardant le retraité qui arrose son jardin en bordure de voie »… Pfister souligne inutilement la monstruosité du propos (p.119) qui ne rassurera pas les gilets jaunes qui se font flinguer ou mutiler tous les dimanches.

On termine : notre auteur dénonce les jeunes bobos d’alors, « les baskets si sensibles à la pollution et à la protection de la nature… ». Il rappelle que bien avant le navrant Hollande, Mitterrand et ses socialos se montrèrent de « parfaits porte-paroles de l’OTAN », d’ailleurs ponctuellement « pris à contre-pied » (p.155) par le revirement américain et soviétique d’alors !

Conclusion : « la gauche pue » ; certes, mais elle reste au pouvoir car elle pue comme ce pays, ni plus ni moins.

J’oubliais Notre-Dame. On va la relooker et en faire un musée-shopping centre-salle de spectacle, ce qu’elle est déjà. Il y a longtemps que ce n’est plus une Eglise et il y a longtemps que l’église catho a crevé. Voyez mon texte sur Swift-Hazard-Michelet-Feuerbach. Le catholicisme est un conglomérat de zombis, de Tartufes, d’octogénaires (Bergoglio fait fuir les jeunes) qui subiront tout.

A propos de la profanation des grands travaux mitterrandiens, Pfister parle déjà de « monarchie culturelle » et de cet « habillage administratif des foucades royales (façades, Louvre, Beaubourg, Orsay, Bastille, bibliothèque). » Il ajoute que « le président s’est offert tous les symboles antiques de la gloire et de l’immortalité » (p.167), ce qui est un « aveu d’inquiétude pour ce jeune chrétien » qui épatait notre couillon Mauriac ! Bloy ou Bernanos savaient mieux que le catho moderne avait muté en rentier humanitaire bon à voter progressiste-humanitariste-impérialiste-je-m’en-foutiste !

Et pour ceux qui se gonflent avec l’affaire Benalla, on recommandera cette perle : « la France socialiste supporte sans broncher les extravagances des vigiles de luxe de l’Elysée… »

Le pamphlet est un genre qui vieillit bien.

Source

Thierry Pfister – Lettre ouverte à la génération Mitterrand qui marche à côté de ses pompes (Albin, Michel, 1989)

00:43 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : france, françois mitterrand, thierry pfister, emmanuel macron, nicolas bonnal, europe, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 29 février 2016

Le dernier coup de Jarnac de François Mitterrand

Salan/’t Pallieterke :

Le dernier coup de Jarnac de François Mitterrand

Naguère, nous avions évoqué dans cette rubrique française l’avalanche de livres récemment publiés à l’occasion du vingtième anniversaire du décès de l’ancien Président français François Mitterrand. Dans cette masse de bouquins, un seul n’a pas vraiment été recensés mais il mérite une attention toute particulière : Dites-leur que je ne suis pas le diable (Plon, 2016, 188 p.). Ce livre est dû à la plume de Georges-Marc Benamou. Ce journaliste a suivi Mitterrand de très près au cours des dernières années de sa vie. Juste après la mort du Président, Benamou avait écrit Mémoires interrompues, soit les mémoires incomplètes de Mitterrand. En 1997, parait Le dernier Mitterrand, ouvrage consacré aux mille derniers jours de la vie du président socialiste. Dites-leur que je ne suis pas le diable en est une sorte de complément. On y trouve un florilège de commentaires et d’analyses posés par Mitterrand dans ses dernières années. Il s’agit de citations non encore publiées à ce jour. Benamou analyse en profondeur une série de controverses relatives au Mitterrand âgé, malade et mourant. Ainsi, Benamou analyse la dernière allocution de Mitterrand à la télévision, à la fin de l’année 1994. Mitterrand avait dit qu’il « croyait en les forces de l’esprit ». Et qu’à la fin de l’année 1995, il écouterait le message du Nouvel An du nouveau Président du « lieu où il se trouverait ». Ce fut donc un discours à connotations religieuses évidentes. En France, où l’église et l’Etat sont strictement séparés, ce ton religieux était inédit. Mitterrand avait éprouvé du plaisir en assistant au tollé que son discours avait suscité. « Vous avez vu ? », demandait à Benamou un Mitterrand rigolard, « j’ai osé ! ». A la fin de sa vie, Mitterrand était fasciné par la mort. Ou mieux : par le passage de la vie après la mort. Il en parlait à des médecins, des philosophes, des théologiens.

Naguère, nous avions évoqué dans cette rubrique française l’avalanche de livres récemment publiés à l’occasion du vingtième anniversaire du décès de l’ancien Président français François Mitterrand. Dans cette masse de bouquins, un seul n’a pas vraiment été recensés mais il mérite une attention toute particulière : Dites-leur que je ne suis pas le diable (Plon, 2016, 188 p.). Ce livre est dû à la plume de Georges-Marc Benamou. Ce journaliste a suivi Mitterrand de très près au cours des dernières années de sa vie. Juste après la mort du Président, Benamou avait écrit Mémoires interrompues, soit les mémoires incomplètes de Mitterrand. En 1997, parait Le dernier Mitterrand, ouvrage consacré aux mille derniers jours de la vie du président socialiste. Dites-leur que je ne suis pas le diable en est une sorte de complément. On y trouve un florilège de commentaires et d’analyses posés par Mitterrand dans ses dernières années. Il s’agit de citations non encore publiées à ce jour. Benamou analyse en profondeur une série de controverses relatives au Mitterrand âgé, malade et mourant. Ainsi, Benamou analyse la dernière allocution de Mitterrand à la télévision, à la fin de l’année 1994. Mitterrand avait dit qu’il « croyait en les forces de l’esprit ». Et qu’à la fin de l’année 1995, il écouterait le message du Nouvel An du nouveau Président du « lieu où il se trouverait ». Ce fut donc un discours à connotations religieuses évidentes. En France, où l’église et l’Etat sont strictement séparés, ce ton religieux était inédit. Mitterrand avait éprouvé du plaisir en assistant au tollé que son discours avait suscité. « Vous avez vu ? », demandait à Benamou un Mitterrand rigolard, « j’ai osé ! ». A la fin de sa vie, Mitterrand était fasciné par la mort. Ou mieux : par le passage de la vie après la mort. Il en parlait à des médecins, des philosophes, des théologiens.

La controverse des ortolans

Le nouveau livre de Benamou nous apprend que Mitterrand a cessé de s’alimenter le jour du Nouvel An, 1 janvier 1996. Il ne prit plus aucun médicament. Le 8 janvier, il mourut. Le soir de la Saint-Sylvestre, il avait pris un ultime repas. Benamou l’avait déjà évoqué dans Le dernier Mitterrand. L’ancien président avait d’abord ingurgité quelques bonnes huîtres. Ensuite, il prit une délicatesse du Pays des Landes, une région du Sud-ouest de la France, où Mitterrand possédait une résidence, à Latche, où il passa sa dernière Saint-Sylvestre.

Cette délicatesse du dernier repas de Mitterrand consistait en ortolans. Ce sont de petits oiseaux que l’on capture, que l’on engraisse et puis que l’on noie vivants dans l’armagnac. Ils sont ensuite rôtis au four. On doit les manger tout entiers, os et viscères compris. Pour manger ce met de manière traditionnelle, on doit se pencher sur le récipient contenant les ortolans, se placer une serviette sur la tête pour se régaler des odeurs de l’armagnac.

Cette délicatesse du dernier repas de Mitterrand consistait en ortolans. Ce sont de petits oiseaux que l’on capture, que l’on engraisse et puis que l’on noie vivants dans l’armagnac. Ils sont ensuite rôtis au four. On doit les manger tout entiers, os et viscères compris. Pour manger ce met de manière traditionnelle, on doit se pencher sur le récipient contenant les ortolans, se placer une serviette sur la tête pour se régaler des odeurs de l’armagnac.

Lorsque Benamou raconta cette anecdote pour la première fois, cela provoqua une avalanche de critiques. Quelques personnages de l’entourage de Mitterrand se sont empressés de dire que le Président moribond n’avait nullement avalé ces oiseaux. Car les ortolans sont une espèce désormais protégée. Ce démenti est faux, affirme Benamou dans son dernier ouvrage de 2016. Les faits sont exacts, nous dit-il. Ce fut par ailleurs un camarade du PS français, Henri Emmanuelli, qui fit livrer à temps les ortolans à Latche. Benamou voit dans ce plat traditionnel des Landes tout un symbole : les ortolans, dans les œuvres de La Fontaine et de Balzac sont un repas de roi.

Les avocats de province

Mitterrand n’aurait pas été lui-même s’il n’avait pas donné, en ses heures ultimes, quelques coups de canifs, bien acérés, à la classe politique. Le livre Dites-leur que je ne suis pas le diable contient quelques belles perles à ce niveau. Quand il s’agit du PS, Mitterrand est vraiment assassin. Dans le lot des socialistes français, il ne voit personne capable de lui succéder. Il ne cite même pas le Président actuel, François Hollande. Les dirigeants du PS sont, selon les Mitterrand des derniers mois, des « avocats de province », ce qu’il était lui-même dans ses jeunes années, dans sa Charente natale. En 1995, lors des Présidentielles, il a soutenu implicitement le néo-gaulliste Jacques Chirac contre le candidat socialiste Lionel Jospin. Mitterrand n’avait pas une haute opinion des autres dirigeants socialistes, comme Pierre Mendès-France. Quant à l’agitation gauchiste de mai 68, il eut ces mots : « Tous des fous ! » ou « Des enfants gâtés de la petite bourgeoisie catholique ».

Mitterrand n’aurait pas été lui-même s’il n’avait pas donné, en ses heures ultimes, quelques coups de canifs, bien acérés, à la classe politique. Le livre Dites-leur que je ne suis pas le diable contient quelques belles perles à ce niveau. Quand il s’agit du PS, Mitterrand est vraiment assassin. Dans le lot des socialistes français, il ne voit personne capable de lui succéder. Il ne cite même pas le Président actuel, François Hollande. Les dirigeants du PS sont, selon les Mitterrand des derniers mois, des « avocats de province », ce qu’il était lui-même dans ses jeunes années, dans sa Charente natale. En 1995, lors des Présidentielles, il a soutenu implicitement le néo-gaulliste Jacques Chirac contre le candidat socialiste Lionel Jospin. Mitterrand n’avait pas une haute opinion des autres dirigeants socialistes, comme Pierre Mendès-France. Quant à l’agitation gauchiste de mai 68, il eut ces mots : « Tous des fous ! » ou « Des enfants gâtés de la petite bourgeoisie catholique ».

A propos du jeune homme qu’était encore Nicolas Sarkozy en 1995, Mitterrand disait qu’il fallait s’en méfier : « C’est un grand cynique ». Alain Juppé, disait-il, « avait certes les allures d’un homme d’Etat ». Mais il n’y aurait plus jamais de grand président, selon Mitterrand. Il disait de lui-même qu’il était le dernier grand président de la France. Ultérieurement, l’Europe dominera tout, pensait-il. Il ne pouvait évidemment pas prévoir la crise actuelle qui frappe l’Europe.

10.000 Français seulement ont entendu De Gaulle en juin 1940

A la fin de sa vie, Mitterrand donna également un coup de canif au prestige de son grand rival, Charles De Gaulle. Selon Mitterrand, son appel du 18 juin 1940, lancé depuis Londres pour inciter les Français à reprendre le combat contre l’Allemagne nationale-socialiste, n’a eu aucun impact au départ. Seulement 10.000 Français l’auraient entendu, affirmait Mitterrand. Et : « entendu par hasard. Le 18 juin en soi, ce ne fut rien. C’est plus tard qu’on en fit un mythe ». Mitterrand a toujours indirectement défendu le Maréchal Pétain et le régime de Vichy, jusqu’à la fin de sa vie. Il considérait la résistance intérieure, dont il fit partie, comme plus importante que celle orchestrée depuis Londres.

Salan/’t Pallieterke.

(article paru dans « ‘t Pallieterke », Anvers, 25 février 2016).

00:05 Publié dans Histoire, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : françois mitterrand, france, histoire, biographie, hommage, livre |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 19 août 2015

François Mitterrand: European Statesman, Anti-American, & Judeophobe

François Mitterrand:

European Statesman, Anti-American, & Judeophobe

President François Mitterrand is a notoriously ambiguous figure and one which, indeed, is an object of both interest and repulsion for the European Right. In his trilogy of little memoirs, hastily written at the end of his life, the president and founder of the European Union makes clear that his passion for “European integration” was founded upon a hostility to the United States of America’s domination of the Old Continent. Intense hostility to American power as well as Jewish power is also evident from private comments he made to his friends and associates. Yet, Mitterrand was also instrumental in the ostracism and persecution of French nationalists from the 1980s onwards.

Mitterrand had been traumatized by the Fall of France in 1940 – during which he had been captured as a soldier before escaping to Vichy after two previous failed attempts. He had personally witnessed European nations’ fratricidal war and calamitous fall from world-hegemony to imperial dependencies of the American and Soviet superpowers. The solution, as he saw it, was eternal peace in Europe and the creation of a European superpower through a fusion of nations, and in particular of France and Germany.

Hostility to American power is evident throughout Mitterrand’s memoirs. He says he rejected the proposed European Defense Community in the 1950s – which would have created a kind of European army made up of French, West German, Italian, and Benelux troops – because it would have been under effective American control:

To refuse the [European Defense Community] was to take the risk of knocking down the fragile edifice of the emerging Europe. To accept it would be a contradiction. To build the Europe of generals before a serious embryo of political authority existed, especially in this period of cold war, left the field too open to general staffs who would have been in a position to determine the fate of Europe and of the countries making it up through the military necessities they would have alone been judges of. And as speaking of general staffs in the plural was in addition no more than a fiction, this defense community would only have been an additional instrument at the service of the Pentagon. That is to say of the Americans. I had not forgotten that at [Georges] Bidault’s request [John] Foster Dulles had gone so far as to imagine deploying the atomic bomb in Vietnam. I could not conceive of Europe being so colonized, and I feared would be destroyed both the body and the soul of what appeared to me as the great ambition of men of my time.[1]

Mitterrand’s attitude towards U.S. influence in Europe had not fundamentally changed between the 1950s and 1990s. He said on the American view of post-Cold War Europe: “the concept of European unity did not mean the same reality depending on if one was American or French.”[2] He rejected closer ties with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who was gravely concerned about the return of German power, citing the same concerns:

Great Britain did not have sufficient leeway to escape the control of the United States, and I would not exchange European construction, of which Federal Germany was one of the pillars, for a Franco-English entente which was desirable but reduced to good wishes.[3]

In private, Mitterrand would go further, telling the journalist Georges-Marc Benamou, with whom he was co-writing one of his memoirs:

France is at war with America. Yes, a constant war, a vital war, an economic war, a war without death. In appearance. Yes, they are very tough, the Americans, they are rapacious, they want undisputed power over the world . . . You saw, after the Gulf war, that they wanted to control this part of the world. They left nothing to their allies.[4]

Certainly, those on the Right have long lamented that after the Second World War all the nations of Europe were subjected to the Soviet and American Empires. The Soviet Union imposed crude military coercion. The United States in contrast reduced Western Europe to a fluctuating combination of economic, military-atomic, political, and, most perniciously, cultural dependence.[5]

But why was Mitterrand so concerned with American power over Europe? What, exactly, is the problem from a so-called universalist liberal-democratic perspective? Mitterrand’s private comments perhaps provide an indication. On May 17, 1995, his last day in office as president, Mitterrand told a friend inquiring about the continuing media-political campaign surrounding his association with former Secretary-General of the Police René Bousquet (who had deported Jews during the Second World War): “You are observing here the powerful and harmful influence of the Jewish lobby in France.”[6] If France, according to François Mitterrand, suffers from “the powerful and harmful influence of the Jewish lobby,” well then what dark forces of disintegration, eternally hostile to Europe, are lurking in America?

Mitterrand the European and Prussophile

Perhaps surprisingly for a Frenchman, Mitterrand saw the shattered German realm of Prussia as an important part of Europe’s redemption. He considered Prussia’s destruction by the Allies in 1945 as a great injustice designed to “strike Germany to the head,” reducing that great nation to decerebrated impotence. Mitterrand notes: “The influence of the United States exercised itself more strongly over the Federal Republic than over France – or at least with more success.”[7] But the Germans, unlike the British, at least wanted to “build Europe.”

Mitterrand sharply distinguishes between the culture and civilization of Prussia and National Socialism.[8] He seems to imagine German Reunification as a kind of return of Prussia to the Federal Republic:

Prussia, home of civilization and culture, inseparable from the civilization and culture that we, Frenchmen, claim as our own . . . before the end of the century Prussia would reappear in her real dimension, one of the richest reservoirs of men and means of Europe and Germany.[9]

Germany would then find its “head” through reunification with “Prussia,” which in turn would free Europe, through Germany’s union with France.

Indeed, Mitterrand went so far, in one of his last speeches in Berlin, to praise the courage of the Third Reich’s soldiers, offending many Jews:

I knew what there was of strong in the German people, its virtues, its courage, and his uniform matters little to me, and even the idea which inhabited the spirit of these soldiers who would die in such large numbers. They were brave, they accepted to lose their lives. For a bad cause, but their gesture had nothing to do with that. They loved their country.[10]

In any event, Mitterrand’s Prussophilia was too optimistic to not say archaic. Prussia is not reborn. Reunification, in destroying the oddly national socialist German Democratic Republic,[11] actually furthered Germany’s demographic collapse with a sharp fall of fertility in the east and continued economic retardation. But there are flickers in the embers: The Patriots Against the Islamization of the West (PEGIDA) protests are strongest in former Prussia, and it is eastern Germans who have radicalized Alternative for Germany (AfD) towards focus against immigration.

Mitterrand rejected the “Europe of Generals” in the 1950s. Yet he proved was the single most important figure in pushing for the “Europe of Bankers” created by the Maastricht Treaty in the 1990s, with its unlimited free movement of capital and its formal reduction of states to dependence upon financial markets. But Mitterrand apparently hoped this would be compensated by the creation of a European common currency – the écu or the Euro – and a powerful, autocratic European Central Bank. In destroying the Deutsche Mark and creating a formidable European currency to rival the U.S. dollar, Mitterrand believed the monetary dominance of the German Bundesbank and of the U.S. Federal Reserve would be ended. The Mitterrandian poetry reaches its greatest heights on this theme of Franco-German reconciliation and European power:

The incessant tumult of History teaches the vanity of treaties as soon as the balance of power changes. . . . I cannot give up however of the idea that a society can survive only by its institutions. So it will be with Europe. Given that everything thus far rests upon force which itself gives way only to violence, let us break this logic and replace it with free contract. If the community, the daughter of reason, adopts lasting structures, victor, vanquished, these notions will belong to our prehistory. The smallness of our continent, the birth of the [European] Community which includes two thirds of its inhabitants, the need felt in both the east and West of Europe to exist and influence the destiny of the planet by widening the vice which, from Asia and America, is closing upon us, are pushing for this realization. I dream of the predestination of Germany and France, which geography and their old rivalry designate to give the signal. I also work towards this. . . . If they have kept within themselves the best of what I do not hesitate to call their instinct of greatness, they will understand that this here is a project worthy of them. I am drawing a design which I know will be muddled, compromised year by year, beyond this century. . . . France is always tempted by withdrawal upon herself and the epic illusion of glory in solitude . . . The great powers of the rest of the world will seek to ruin the arrival of an order which is not theirs. Those nostalgic for death on the street corner, of the hospital one crushes beneath bombs, of car bombs for the sole honor of raising up a plot of land as a nation, with its border posts at the first hedge, will wrap themselves in the folds of a thousand and one flags . . .[12]

Pétain and Mitterrand

Mitterrand’s Failure

France, whether embodied in a De Gaulle, a Mitterrand, or a Le Pen, has often provided inspiration for Europeans in other countries who dream of freeing the Old Continent from foreign domination. The French enjoyed a relative freedom and national ambitions far beyond anything the occupied Germans could be allowed to have.

France’s decline is viscerally-felt and painful for the French. Indeed, the French political class, at least from the beginning of the presidency of Charles de Gaulle in 1958 to that of Nicolas Sarkozy in 2007, was sincerely motivated to strengthen French and Europe as a power in the world. This was evident in autonomy within NATO, a relatively independent “Arab policy,” the push for European integration, efforts to promote French language and culture through various protectionist measures, and opposition to the 2003 Iraq War. These efforts were overwhelmingly conservative ones, however, and completely disregarded the deep roots of the nation’s decadence, and were thus doomed to failure.

Mitterrand himself was haunted by the decline of France. He told Benamou:

In fact, I am the last of the great presidents . . . Well, I mean the last in the line of De Gaulle. After me, there will be no more in France . . . Because of Europe . . . Because of globalization . . . Because of the necessary evolution of institutions.[13]

Charles de Gaulle had a similar view. But while the General believed Europe had been strongest, most free and alive, when there had been vigorous warring nations, Mitterrand famously declared that “Nationalism is war!”

Mitterrand was entirely complicit in the demonization of European nationalisms and the rise of the Shoah to what Éric Zemmour has called “the official religion of the French Republic,”[14] notably with the passage of the Fabius-Gayssot Act criminalizing critical historical study of the Holocaust. He empowered Jewish “anti-racist” organizations such as the CRIF, the LICRA, and SOS Racisme. He participated in a concerted police and politico-media campaign to frame the Front National for the desecration of a Jewish cemetery at Carpentras in 1990, indefinitely excommunicating that party from respectability in the eyes of mainstream public opinion. Mitterrand did this for personal and political gain, pandering to the most powerful ethnic networks in the country, and working to keep the Socialist Party in power, despite its manifest economic failures, by dividing the opposition into a “mainstream” right and a “far-right.”

Alain Soral has said that whomever rises by the Jews must fall by the Jews. And, sure enough, Mitterrand was caught in his web of sins: He empowered Jewish organizations to persecute revisionist historians and nationalist activists in the name of the Shoah, but in turn an ever-more-vocal fraction of this same community resented Mitterrand’s own so-called “ambiguities” on the Vichy period, namely his youthful admiration for Marshal Philippe Pétain, his postwar association with Bousquet, and his refusal to officially debase France by recognizing collective and national guilt for participation in the Holocaust.[15]

Characteristically, Mitterrand chose to write his three memoirs with the collaboration of three Jews: the infamous Elie Wiesel, the young Georges-Marc Benhamou, and the atrociously-botoxed publisher Odile Jacob. This no doubt reflected the density of Jewish networks around Mitterrand, many in which still had affection for the old leader, but also (especially in the case of the High Priest of Holocaustianity Wiesel) an attempt by Mitterrand to secure his legacy and respectability before the Jewish community.

Mitterrand’s attempts to appease ethnocentric Jews[16] naturally failed. He continued to be attacked until his dying day and, after his death, Wiesel all but called the recently-departed president a liar, accusing him of “a deformation of facts” and “falsehood” concerning “that bastard Bousquet.”[17] Benamou also repeatedly tried to get Mitterrand to confess some imagined guilt, but failed:

Actually, François Mitterrand did not believe in the specificity of the holocaust, despite his fascination for the Old Testament and his ‘friendship for the Jewish people.’ He had not understood the Twentieth Century and its tragedy. . . . He had always been indifferent to the Jewish question, and that is a positive point, in view of his milieu. The flip side is that this indifference never allowed him to understand the scale of the Jewish tragedy. He was a man of the Nineteenth Century, that is, a man who considered the greatest tragedy of all time to be Verdun, those thousands square kilometers overturned by bombs, that ossuary. . . .

But the cornered monarch had closed in on himself. This confrontation had taken for him such an obsessive turn that to concede apologies on behalf of France, in his eyes, was a personal humiliation. He had convinced himself of this and became again, in these movements, that Gaulish chieftain that I did not like very much.[18]

Indeed, neither Wiesel nor Benamou could tolerate the arrogance of a goy prince who would put his own dead, those French peasants rooted for millennia, before those of their own Tribe. Mitterrand could protest to Benamou that wartime was complicated: “Young man, you do not know what you are talking about,” to no avail.

Mitterrand apparently believed that Europe could become a world-power despite the hegemony of a hostile anti-European culture, despite the demonization of any European ethno-national self-assertion, and despite the founding of the “European Union” on fundamentally neoliberal and plutocratic principles of open borders.

So far, his œuvre has singularly failed, with the Eurozone in particular being a byword for economic failure and permanent crisis. Perhaps this is unsurprising. Indeed, even in his own day Mitterrand had a singular contempt for the man he had appointed to oversee – or perhaps, merely, spectate over – his grand design: European Commission President Jacques Delors. Mitterrand mocks Delors as a non-entity, doing who-knows-what in Brussels, superficially idealized by the French media. He reacts to Delors’ declaration that he would not be running for president despite the superficial polls in his favor: “Oh, what a non-event on live television, that doesn’t happen every day!”[19] It seems very strange of Mitterrand to be so invested in the European Union as his “legacy,” and yet be so mocking of his chosen executor. Indeed, elsewhere he argues that European leaders will know to be conciliatory and push forward with integration precisely because of the fragility of the project: “They know that the European Meccano would collapse if one piece were removed.”[20] That is not exactly a vote of a confidence in a sound foundation.

The ultimate legacy of the flawed Union Mitterrand bestowed upon Europe remains unclear. Perhaps, it is a bridge too far in transnationalism which will, in a dialectical response, bring about a nationalist regime firmly dedicated to the restoration of the nation-state. Perhaps, as Guillaume Faye hoped, the Union can in time be hijacked as an effective power which would enable Europe’s emancipation from the small-states’ seductive temptation of collaboration with American political and military power. Perhaps the whole EU project will simply prove irrelevant to the continued steady decline of Europeans in the face of American cultural-political hegemony and Afro-Islamic demographic submersion.

And what can we conclude on Mitterrand? Every man is indelibly marked by the world of his childhood. In the case of Mitterrand, he was raised a French-speaking, Right-wing Catholic milieu in which America, Jewry, and high finance were seen with suspicion as corrupting and overlapping entities. The values of Mitterrand’s childhood milieu had many similarities with those of a Charles de Gaulle, a Léon Degrelle, or a Hergé, men who also dreamed, each in their way, of a Europe free from America.

There is little logic in Mitterrand’s sinuous rise to power besides perhaps a hostility to an overbearing De Gaulle, openness to alliance with the French Communists, and a good feel for the political center of gravity of the country. Mitterrand served as a decorated Vichy official, joined the Resistance, quickly rose as a postwar minister in the corrupt, parliamentary Fourth Republic and pledged to defend French Algeria. After over two decades in the desert of opposition, he finally became the first Socialist President of the Fifth Republic in 1981, after which he quickly had to renege upon his exaggerated social promises, but maintained his power in part through collaboration with ethnocentric Jewish networks.

In a sense, Mitterrand betrayed the values of his childhood and yet he never went far enough to fully appease a large fraction of the Jewish community. I cannot help but think, in his sincere reconciliation with Germany and his clumsy efforts to set the foundations for a European superpower, Mitterrand also sought to redeem his European soul.

Notes

1. François Mitterrand, Mémoires interrompus (Paris: Odile Jacob, 1996), 212-3.

2. François Mitterrand, De l’Allemagne, de la France (Paris: Odile Jacob, 1997), 45.

3. Mitterrand, De l’Allemagne, 43.

4. Georges-Marc Benamou, Le dernier Mitterrand (Paris: Plon, 1996), 52.

5. Kevin B. MacDonald, The Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth-Century Intellectual and Political Movements (1st Book Library: 2002).

6. Renaud Dely, “Quand Mitterrand parlait du ‘lobby juif’,” Libération, August 27, 1999. http://www.liberation.fr/politiques/1999/08/27/quand-mitterrand-parlait-du-lobby-juif-jean-d-ormesson-revele-des-propos-tenus-en-1995_280524

7. Mitterrand, De l’Allemagne, 139.

8. Indeed, anti-Nazism is the stated center of Mitterrand’s moral universe. In fact there are both breaks and continuity between Frederick the Great’s Prussia and Adolf Hitler’s Germany. Among the points of continuity: autocracy, militarism, and sacrifice.

9. Mitterrand, De l’Allemagne, 125.

10. Jean Guisnel, “Mitterrand célèbre les soldats morts, allemands compris,” Libération, May 10, 1995. http://www.liberation.fr/evenement/1995/05/10/mitterrand-celebre-les-soldats-morts-allemands-compris_133400

11. The GDR, despite its obsessive anti-Nazism, appeared very national socialist in its Prusso-Stalinism. Indeed, from a demographic point of view East Germany was a superior regime, maintaining higher birth rates and encouraging the more educated to have children.

12. Mitterrand, De l’Allemagne, 128-9.

13. Benhamou, Mitterrand, 146. Indeed, Mitterrand seems to be the last French president whose name American journalists can remember, as miserable an indicator as any. http://www.ohmymag.com/le-petit-journal/le-petit-journal-les-journalistes-americains-ont-du-mal-avec-le-president-francais_art73699.html

14. Éric Zemmour, “The Rise of the Shoah as the Official Religion of the French Republic,” The Occidental Observer, May 12, 2015. http://www.theoccidentalobserver.net/2015/05/eric-zemmour-the-rise-of-the-shoah-as-the-official-religion-of-the-french-republic/

15. Towards the end of his term as president, Mitterrand famously rejected on live television the Sephardic journalist Jean-Pierre Elkabbach’s relaying Jewish organizations’ demands for “apologies” for Vichy:

Mitterrand: “They will wait a long time. They will not get any. France has no need to apologize, nor has the Republic. I would never accept it. I consider that it is an excessive demand from people who do not deeply feel what it means to be French and the honor of being French, and the honor of the history of France. . . .

Elkabbach: “[You successors] will also feel the pressure.

Mitterrand: [Scoffs.] “Perhaps in a hundred year still too? What does this mean? This maintains hatred and it is not hatred which must govern France.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=owFF0K9-jcs

16. And Wiesel is truly absurdly ethnocentric in his unenlightening book of interviews with Mitterrand. He opens the book with: “For us, Jews,” and never stops. At least half the questions must have a Jewish focus or framing. I am sorry if I must appear unkind but such selfish self-centeredness is rightly mocked. In his interventions, Wiesel mentions the synagogue, the concentration, the psychoanalyst, the Talmudic sage, a Talmudic saying, “the death of a Hasidic master,” the trauma of forgetting his speech scrolls while in Israel (because he is “very pious,” he says), his being raised “the Bible” [sic], the Jewish tradition, the Yiddish writer, the rabbi, Kafka’s equaling Dostoevsky, and on and on and on. As the libertarian comedian Doug Stanhope has put it: “Jew, Jew, Jew, Jew, Jew, Jew, Jew, Jew!” Wiesel also repeatedly, and quite transparently, emotionally manipulates through selective righteous indignation, either to distract (Biafra, Yugoslavia) or to harass the Jews’ enemies (Islamic fundamentalism in Iran and Algeria, Iranian and Libyan efforts to get nuclear weapons . . .) without a peep on Israel’s crimes against the Palestinians or its nuclear weapons. François Mitterrand and Elie Wiesel, Mémoire à deux voix (Paris: Odile Jacob, 1997).

17. Christophe Barbier, “Wiesel Contre Mitterrand,” L’Express, October 3, 1996. http://www.lexpress.fr/informations/wiesel-contre-mitterrand_618526.html

18. Benamou, Mitterrand, 199-201.

19. Benamou, Mitterrand, 90.

20. Mitterrand, De l’Allemagne, 129-30.

00:05 Publié dans Affaires européennes, Biographie, Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : france, françois mitterrand, histoire, biographie, europe, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 22 mai 2011

François Mitterrand & the French Mystery

François Mitterrand & the French Mystery

Dominique Venner

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Translated by Greg Johnson

In the center of all the questions raised by the sinuous and contradictory path of François Mitterrand is the famous photograph of the interview granted to a young unknown, the future socialist president of the Republic, by Marshall Philippe Pétain in Vichy, on October 15th, 1942.

In the center of all the questions raised by the sinuous and contradictory path of François Mitterrand is the famous photograph of the interview granted to a young unknown, the future socialist president of the Republic, by Marshall Philippe Pétain in Vichy, on October 15th, 1942.

This document was known to some initiates, but it was verified by the interested party only in 1994, when he saw that his life was ending. Thirty years earlier, the day before the presidential election of 1965, the then Minister of the Interior, Roger Frey, had received a copy of it. He demanded an investigation which went back to a former local head of the prisoners’ association, to which François Mitterrand belonged. Present at the time of the famous interview, he had several negatives. In agreement with General de Gaulle, Roger Frey decided not to make them public.

Another member of the same movement of prisoners, Jean-Albert Roussel, also had a print. It is he who gave the copy to Pierre Péan for the cover of his book Une jeunesse française (A French youth), published by Fayard in September 1994 with the endorsement of the president.

Why did Mitterrand suddenly decide to make public his enthusiastic Pétainism in 1942–1943, which he had denied and dissimulated up to that point? It is not a trivial question.

Under the Fourth Republic, in December 1954, from the platform of the National Assembly, Raymond Dronne, former captain of the 2nd DB, now a Gaullist deputy, had challenged François Mitterrand, then Minister of the Interior: “I do not reproach you for having successively worn the fleur de lys and the francisque d’honneur [honors created by the Third Republic and Marhsall Pétain’s French State respectively – Trans.] . . .” “All that is false,” retorted Mitterrand. But Dronne replied without obtaining a response: “All that is true, and you know very well . . .”

The same subject was tackled again in the National Assembly, on February 1st, 1984, in the middle of a debate on freedom of the press. We were now under the Fifth Republic and François Mitterrand was the president. Three deputies of the opposition put a question. Since the past of Mr. Hersant (owner of Figaro) during the war had been discussed, why not speak about that of Mr. Mitterrand? The question was judged sacrilege. The socialist majority was indignant, and its president, Pierre Joxe, believed that the president of the Republic had been insulted. The three deputies were sanctioned, while Mr. Joxe declared loud and clear Mr. Mitterrand’s role in the Résistance.

This role is not contestable and is not disputed. But, according to the concrete legend imposed after 1945, a résistant past is incompatible with a Pétainist past. And then at the end of his life, Mr. Mitterrand suddenly decided to break with the official lie that he had endorsed. Why?

To be precise, before slowly becoming a résistant, Mr. Mitterrand had first been an enthusiastic Pétainist, like millions of French. First in his prison camp, then after his escape, in 1942, in Vichy where he was employed by the Légion des combattants, a large, inert society of war veterans. As Mitterrand found this Pétainisme too soft, he sought out some “pure and hard” (and very anti-German) Pétainists like Gabriel Jeantet, an old member of the Cagoule [the right-wing movement of the late 1930s dedicated to overthrowing the Third Republic – Trans.], chargé in the cabinet of the Marshal, one of his future patrons in the Ordre de la francisque.

On April 22nd, 1942, Mitterrand wrote to one his correspondents: “How will we manage to get France on her feet? For me, I believe only in this: the union of men linked by a common faith. It is the error of the Legion to have taken in masses whose only bond was chance: the fact of having fought does not create solidarity. Something along the lines of the SOL,[1] carefully selected and bound together by an oath based on the same core convictions. We need to organize a militia in France that would allow us to await the end of the German-Russian war without fear of its consequences . . .” This is a good summary of the muscular Pétainism of his time. Quite naturally, in the course of events — in particular after the American landing in North Africa of November 8th, 1942 — Mitterand’s Pétainism evolved into resistance.

The famous photograph published by Péan with the agreement of the president caused a political and media storm. On September 12th, 1994, the president, sapped by his cancer, had to explain himself on television under the somber gaze of Jean-Pierre Elkabbach. But against all expectation, the solitude of the accused, as well as his obvious physical distress, made the interrogation seem unjust, causing a feeling of sympathy: “Why are they picking on him?” It was an important factor that reconciled the French to their president. It was not an endorsement of a politician’s career. It was Mitterrand the man who had suddenly became interesting. He had acquired an unexpected depth, a tragic history that stirred an echo in the secret of the French mystery.

Note

1. The SOL (Service d’ordre légionnaire) was constituted in 1941 by Joseph Darnand, a former member of the Cagoule and hero of the two World Wars. This formation, by no means collaborationist, was made official on January 12th, 1942. In the new context of the civil war which is then spread, the SOL was transformed into the French Militia on January 31st, 1943. See the Nouvelle Revue d’Histoire, no. 47, p. 30, and my Histoire de la Collaboration (History of collaboration) (Pygmalion, 2002).

Source: http://www.dominiquevenner.fr/#/edito-nrh-54-mitterrand/3845286 [3]

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2011/05/francois-mitterrand-and-the-french-mystery/

00:05 Publié dans Affaires européennes, Histoire, Nouvelle Droite, Politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : france, françois mitterrand, histoire, nouvelle droite, dominique venner, cinquième république |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook