Here’s a headline that deserves some attention: “Russia to China: Together we can rule the world.” It appeared at Politico EU on February 17, and the author was Bruno Maçães, a former Europe minister for Portugal. Maçães wrote, “In the halls of the Kremlin these days, it’s all about China—and whether or not Moscow can convince Beijing to form an alliance against the West.” (Maçães also wrote a book called The Dawn of Eurasia: On the Trail of the New World Order.)

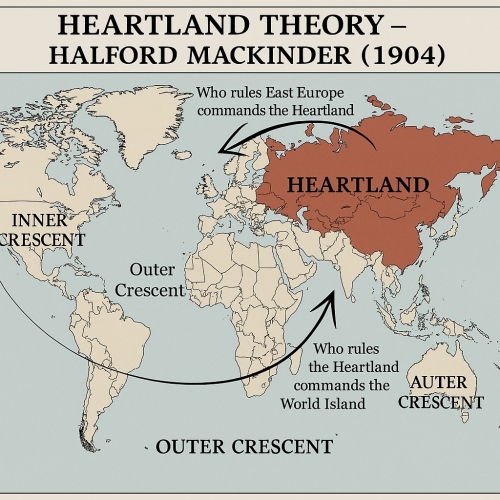

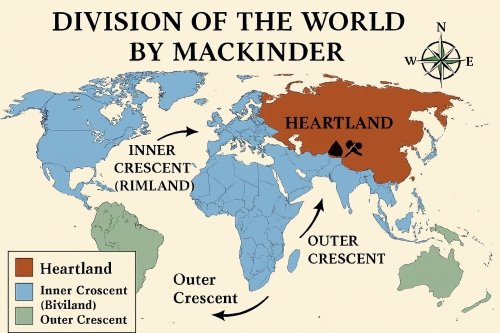

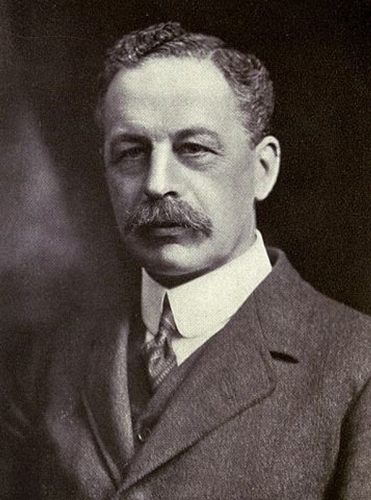

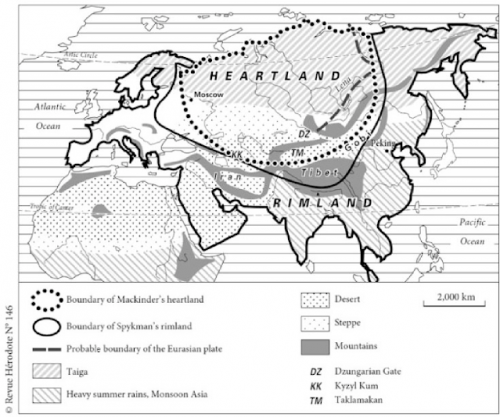

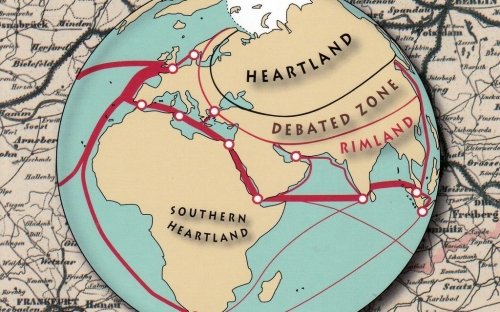

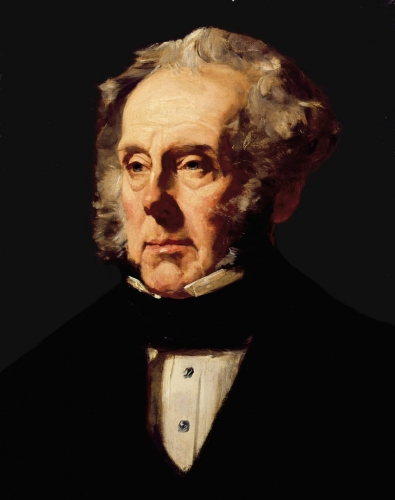

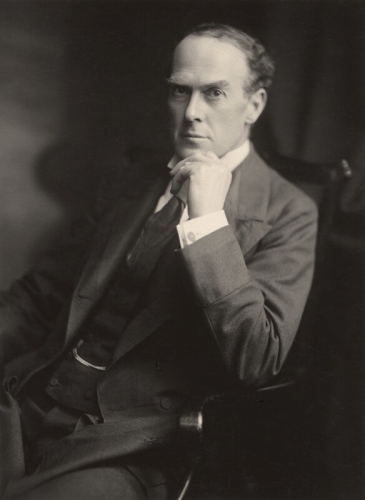

If Maçães is correct in his reporting, then we’re back to the gloomy world of geopolitician Halford MacKinder—although some would say that we never left it.

Back in 1904, Mackinder, a reader in geography at Oxford, published a paper, “The Geographical Pivot of History.” In it, he warned Britain that the strategic value of its key military asset was waning.

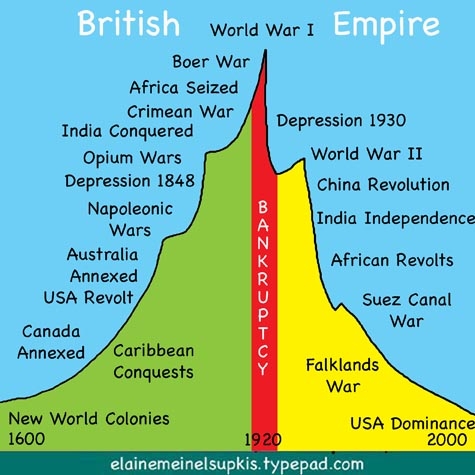

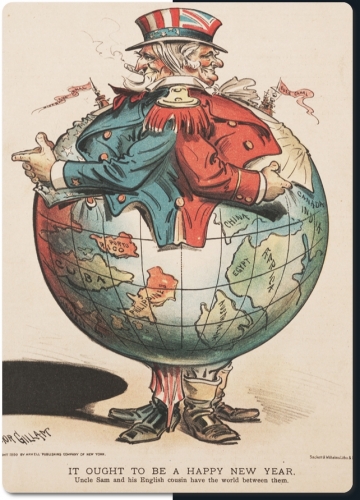

That key asset was the British Navy. For centuries, Britain had mostly relied on naval strength to win wars and maintain the balance of power in continental Europe. During the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), for instance, the British were undistinguished in ground combat, and yet they won big at sea, using their ships to snap up valuable French possessions in North America, Africa, and India.

That key asset was the British Navy. For centuries, Britain had mostly relied on naval strength to win wars and maintain the balance of power in continental Europe. During the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), for instance, the British were undistinguished in ground combat, and yet they won big at sea, using their ships to snap up valuable French possessions in North America, Africa, and India.

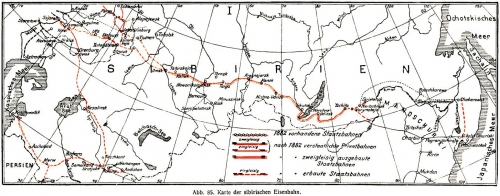

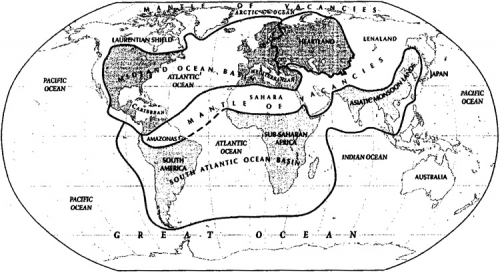

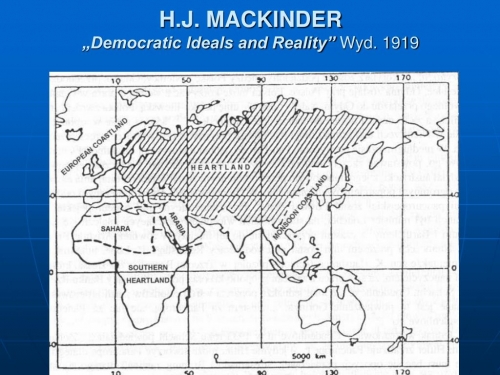

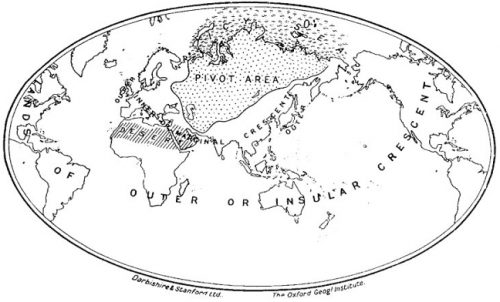

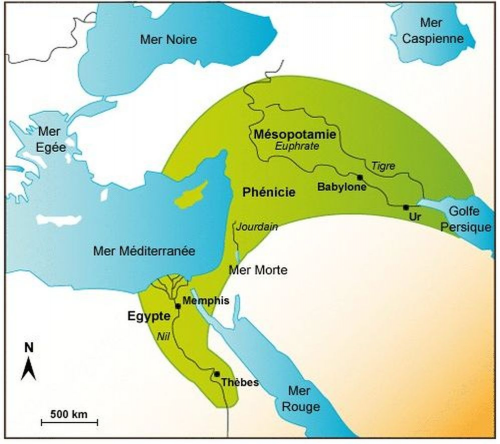

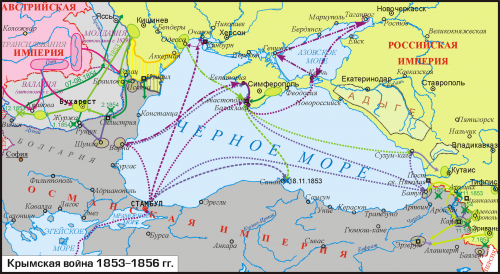

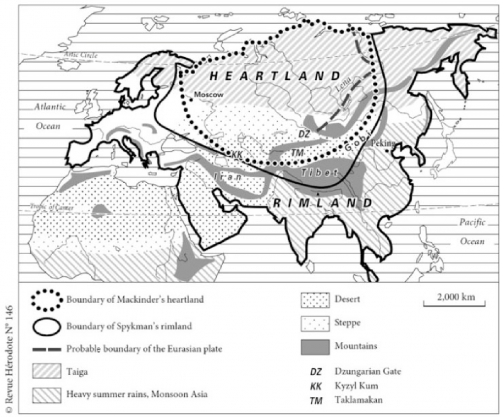

Yet in the 20th century, MacKinder argued, new trends were diminishing the power of fleets. As he wrote, “Trans-continental railways are now transmuting the conditions of land power, and now they can have such an effect on the closed heart-land of Euro-Asia.” Mackinder’s point was that the railroad enabled land powers to send armies quickly to far frontiers:

The Russian railways have a clear run of 6,000 miles from Wirballen [Virbalis in present-day Lithuania] in the west to Vladivostok in the east. The Russian army in Manchuria is as significant evidence of mobile land-power as the British army in South Africa was of sea-power.

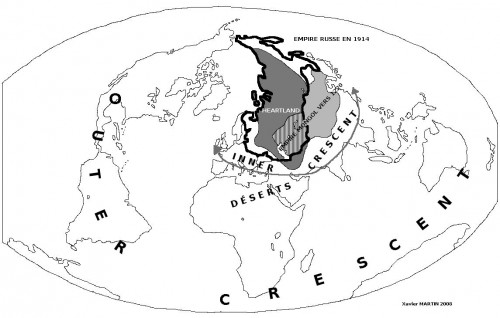

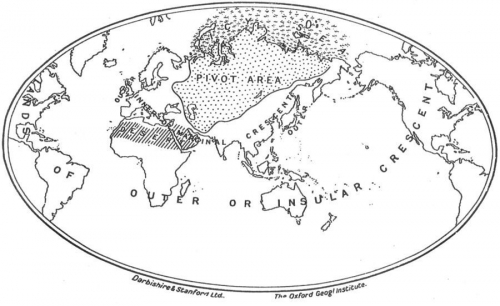

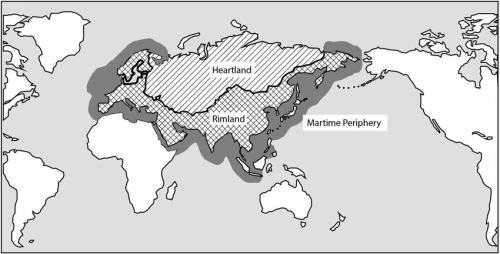

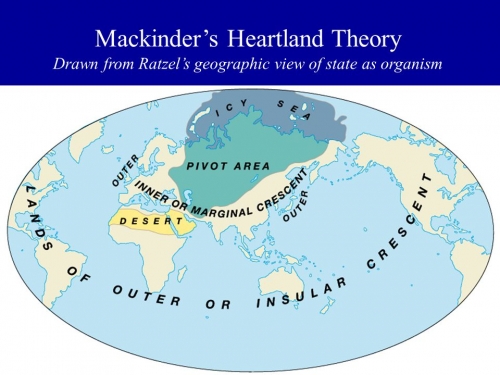

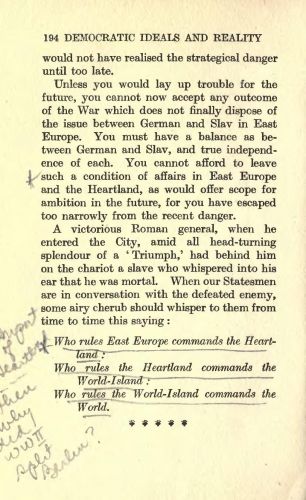

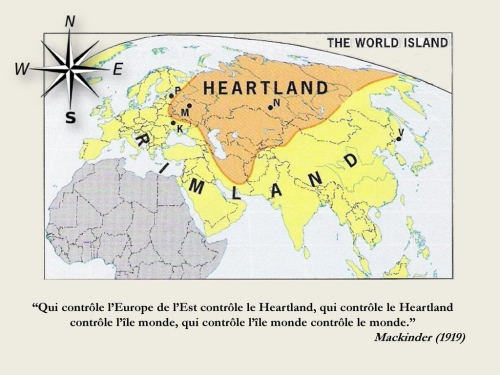

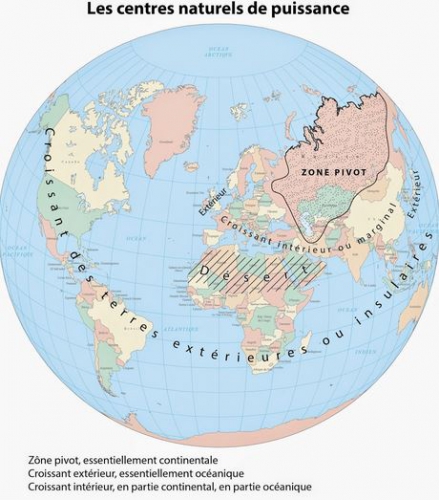

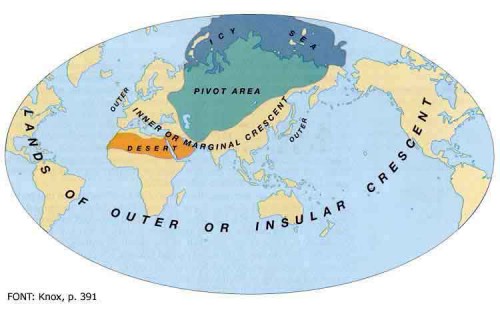

This recent extension of armies on land was ushering in the possibility of an all-powerful “pivot state,” which, according to Mackinder, could lead to “the oversetting of the balance of power in favour of the pivot state, resulting in its expansion over the marginal lands of Euro-Asia.”

This new kind of geopolitical muscle on the Eurasian landmass, he continued, “would permit the use of vast continental resources for fleet-building, and the empire of the world would be in sight” (emphasis added). In other words, a powerful pivot state in Eurasia would threaten Britain’s navy, and thus Britain itself.

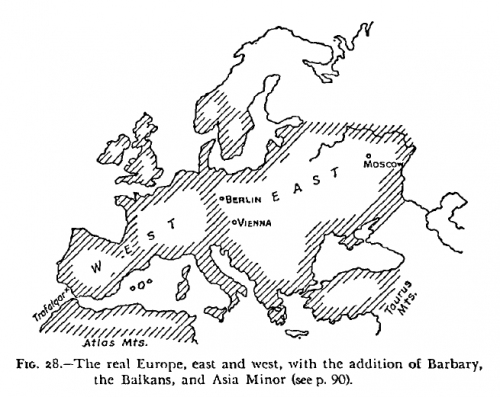

Specifically, Mackinder suggested that Germany and Russia might unite—most likely by conquest—at least part of the Eurasian “world-island.” Or perhaps Japan and China might similarly be joined. Either scenario, Mackinder warned, would be a “peril to the world’s freedom.”

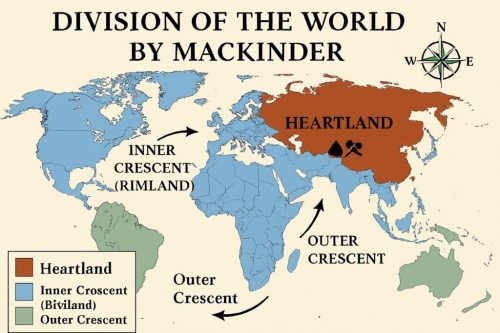

We might add that so far as Mackinder was concerned, a peril to Britain was also a peril to the United States. In Mackinder’s geopolitical reckoning, the two nations were part of the planet’s “outer crescent,” and as such were both less powerful than a united Eurasia—were that ever to happen.

Interestingly enough, at about the same time as Mackinder’s bleak assessment, Sergei Witte, a top minister to Russia’s Czar Nicholas II, was trying to make exactly that scenario come true.

As Witte recorded in his 1915 memoir, he proposed a Eurasian alliance to Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II. As he said to the Kaiser, “Your majesty, picture a Europe that does not waste most of its blood and treasure on competition between individual countries.” That is, the Kaiser might envision a land mass “which is…one body politic, one large empire.” He added:

To achieve this ideal we must seek to create a solid union of Russia, Germany, and France. Once these countries are firmly united, all the States of the European continent will, no doubt, join the central alliance and thus form an all-embracing continental confederation.

Witte records that the Kaiser liked the idea, especially since it specifically excluded Britain. Of course, nothing ever came of the suggestion, and in fact, just a decade later, Germany was at war with Russia, France, and Britain.

Yet the dream of a large alliance endured. In the 1920s, an Austrian, Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi, published a book entitled Pan-Europa, which snowballed into a social movement aimed at uniting the continent. Obviously this effort didn’t get very far, although in subsequent decades, others, too, sought to unify Europe, by means of both war and peace.

So what are we to make of Mackinder’s vision today? In the century since his paper, many power variables have changed. For instance, railroads are not as critically important as they once were.

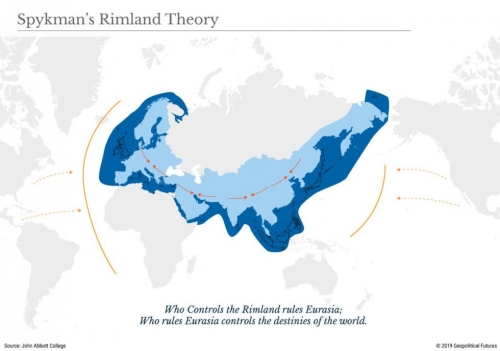

To Mackinder in 1904, a Eurasian land power would have had the advantage of being able to move its forces around by rail, benefiting from interior lines of communication. By contrast, a sea power would need to transport its forces offshore, along the coast of the world-island, a far slower process. That was a good argument at the time, yet post-Mackinder innovations such as the airplane have changed the nature of both combat and transport. And long-range missiles moot distance altogether.

However, there’s still the basic reality that Russia is a great power. And nowadays, of course, China is a far greater power. So if those two countries were ever to form an alliance, they would pose a huge threat to the West—which is exactly the point that Maçães is making.

Of course, it’s far from obvious that Russia and China are destined to be allies. After all, the normal pattern of geopolitics is that adjacent countries are foes, not friends, and Russia and China have been feuding over Siberia, Mongolia, and Central Asia, on and off, for centuries. Yes, it’s true that during Mao’s early years in power, China and Russia were seemingly joined together, but that red fraternalism didn’t last long. The two states fought a series of border skirmishes for six months in 1969.

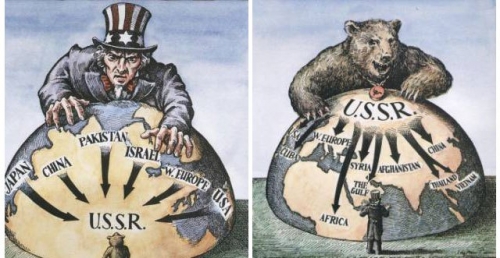

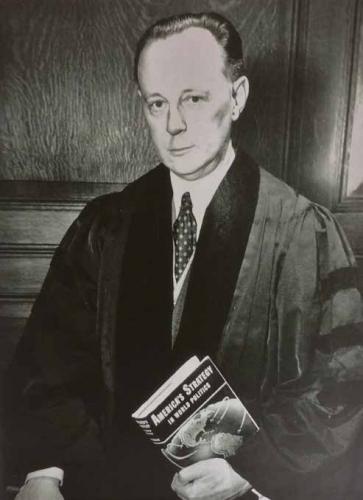

That’s why Richard Nixon’s opening to China in 1972 was so important: it turned the Sino-Soviet split into a tacit Sino-American alliance. Indeed, it’s easy to argue that Nixon’s diplomacy was the turning point in the Cold War, dooming the Russians to defeat.

So we can see, the U.S., being what Mackinder would call an outer-crescent state, benefits when Eurasia is divided.

Unfortunately, subsequent American presidents have not been so wise about keeping the Eurasians at odds with each other. In the ’90s, after the Soviet Union collapsed, Bill Clinton, proto-neocon that he was, chose to expand the NATO alliance so it reached all the way to the Russian border. In so doing, the U.S. won the affection of Estonia—and the enmity of Russia. In Mackinderian terms, that wasn’t such a smart swap.

Then, over the next decade, George W. Bush went full neocon. He turned a justifiable invasion of Afghanistan—what should have been a quick punitive mission and nothing more—into a long-term commitment to “nation-building.” And then came the invasion of Iraq, which was neither just nor smart.

As we know, our gains among Afghans and Arabs have been evanescent, if not negative. Yet in the meantime, both Russia and China had been given good reason to believe that Uncle Sam had long-term designs in Asia—Afghanistan borders both China and the former USSR—and that such designs threatened them both.

As a result, a once-modest Chinese initiative, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), gained both members and real momentum, as Beijing and Moscow worked jointly together to counter American power in their backyard. The SCO is exactly the sort of Eurasian alliance of Mackinder’s nightmare.

As for the European part of Eurasia, the news from the just-ended Munich Security Conference is a bit ominous. The headline from Bloomberg News reads: “China, Russia Join for Push to Split U.S. From Allies.” Of course, the split may already have occurred: The New York Times quotes one “senior German official” saying, “No one any longer believes that Trump cares about the views or interests of the allies. It’s broken.”

Underscoring that anonymous official’s point, Johann-Dietrich Worner, head of the European Space Agency, went on the record to say that his agency ought to be cooperating more with China.

To be sure, it’s hard to believe that the European Union, Russia, and China could all end up on the same side—and so maybe we should choose to believe that it’s simply not possible. Moreover, another important Eurasian country, India, has yet to make plain its strategic choices. And let’s not forget one of those outer-crescent countries, Japan.

Yet one can’t look at a globe—a globe reminding us of the size of Eurasia, home to two thirds of the world’s population—and not think of Mackinder’s grim geopolitical prognosis.

Nobody ever said that Mackinder was an optimist. And come to think of it, in our time, Maçães doesn’t seem to be one either.

James P. Pinkerton is an author and contributing editor at The American Conservative. He served as a White House policy aide to both Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush.

Pourquoi la pensée géopolitique importe

Pourquoi la pensée géopolitique importe

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Er ging davon aus, dass unter anderem die Rohstoffreserven der Weltinsel es ermöglichen würden, von dort aus alle anderen Länder zu beherrschen, also solcher in kontinentaler Randlage und langfristig auch den amerikanischen Kontinent, Japan und Australien. Für Mackinder ist damit die Beherrschung des Kernlandes Eurasien der Schlüssel zur Weltmacht. In Deutschland fand seine Theorie so gut wie keine Rezeption und sein

Er ging davon aus, dass unter anderem die Rohstoffreserven der Weltinsel es ermöglichen würden, von dort aus alle anderen Länder zu beherrschen, also solcher in kontinentaler Randlage und langfristig auch den amerikanischen Kontinent, Japan und Australien. Für Mackinder ist damit die Beherrschung des Kernlandes Eurasien der Schlüssel zur Weltmacht. In Deutschland fand seine Theorie so gut wie keine Rezeption und sein