Nigel Rodgers

The Complete Illustrated Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece [2]

Lorenz Books, 2014

“Western civilization” is certainly not fashionable in mainstream academia these days. Nonetheless, the ancient Greek and Roman heritage remains quietly revered in the more thoughtful and earnest circles. Quite simply, virtually all of our social and political organization, to the extent these are thought out, ultimately go back to Greek forms, reflected in the invariably Greek words for them (“philosophy,” “economy,” “democracy” . . .). Those who still have that instinctive pride of being European or Western always go back to the Greeks, to find the means of being worthy of that pride.

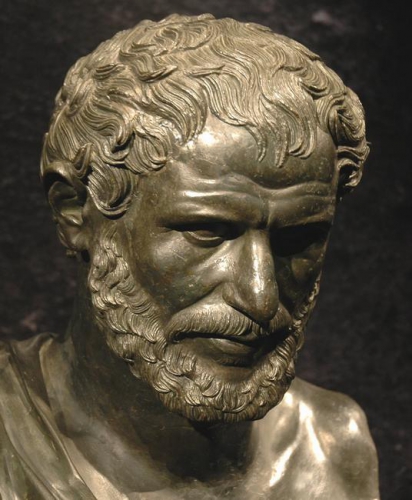

Thus I came to the Illustrated Encyclopedia produced by Nigel Rodgers. Life is short, and lots of glossy pictures certainly do help one get the gist of something. Rodgers does not limit himself to pictures of ancient Greek art, though that of course forms the bulk. There are also photos of the sites today, to better imagine the scene, and many paintings from later epochs imagining Greek scenes, the better show Greece’s powerful influence throughout Western history. The Encyclopedia is divided into two parts: First a detailed chronological history of the Greek world, second a thematic history showing different facets of Greek life.

The ancient Greeks are more than strange beings so far as post-60s “liberal democracy” is concerned. Certainly, the Greeks had that egalitarian and individualist sensitivity that Westerners are so known for.

The ancient Greeks are more than strange beings so far as post-60s “liberal democracy” is concerned. Certainly, the Greeks had that egalitarian and individualist sensitivity that Westerners are so known for.

Many Greek cities imagined that their legendary founders had equally distributed land among all citizens. As inequality and wealth concentration gradually rose over time, advocates of redistribution would cite these founding myths. (Rising inequality and revolutionary equality seems to be a recurring cycle in human history.)

Famously, Athens and various other Greek cities were full-fledged direct democracies, a kind of regime which is otherwise astonishingly rare. This was of course limited to only full male citizens, about 10 percent of the population of this “slave state.” (Alain Soral, that eternal mauvaise langue, once noted that the closest modern state to democratic Athens was . . . the Confederate States of America.)

The Greeks were individualists too, but not in the sense that Americans are, let alone post-60s liberals. Their “kings” seem more like “chiefs,” with a highly variable personal authority, rather than absolute monarchs or oriental despots.

In all other respects, the Greeks were extremely “fash”: misogynistic, authoritarian, warring, enslaving, etc. One could say that, by the standards of the United Nations, the entire Greek adventure was one ceaseless crime against humanity.

The most proto-fascistic were of course the Spartans, that famous militaristic and communal state, often idealized, as most recently in the popular film 300. Sparta would be a model for many, cited notably by Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Adolf Hitler (who called the city-state “the first Volksstaat). Seven eighths of Sparta’s population was made of helots, subjects dominated by the Spartiate full-time warriors.

The Greeks generally were enthusiastic practitioners of racial citizenship. Leftists have occasionally (rightly) pointed to the fact that the establishment of democracy in Athens was linked to the abolition of debt. But one should also know that Pericles, the ultimate democratic politician, paired his generous social reforms with a tightening of citizenship criteria to having two Athenian parents by blood. (The joining of more “progressive” redistribution with more “exclusionary” citizenship makes sense: The more discriminating one is, the more generous one can be, having limited the risk of free-riding.)

In line with this, the Greeks practiced primitive eugenics so as to improve the race. The most systematic in this respect was Sparta, where newborns with physical defects were left in the wilderness to die. By this cruel “post-natal abortion” (one can certainly imagine more human methods), the Spartans thus made individual life absolutely secondary to the well-being of the community. This is certainly in stark contrast to the maudlin cult of victimhood and personal caprice currently fashionable across the West.

Athenian democracy was also known for the systematic exclusion of women, who seemed to have had lives almost as cloistered and private as that of pious Muslims. The stark limitations on sex (arranged marriages, the death penalty for adultery) may have also contributed to the similar Greek penchant for pederasty and bisexuality. Homosexuals were not a discrete social category (how sad for anyone to make their sexual practices the center of their identity!). Homosexual relationships, in parallel to wives, were often glorified as relations of the deepest friendship and entire regiments of male lovers were organized (e.g. the Sacred Band of Thebes [3]), with the idea that by such bonds they would fight to the death.

To this day, it is not clear if we have ever matched the intellectual and moral level of the Greeks (and I do not confuse morality with sentimentality, the recognition of apparently unpleasant truths is one of the greatest markers of genuine moral courage). Considering the education, culture (plays), and politics that a large swathe of the Greek public engaged in, their IQs must have been very high indeed.

Some argue we have yet to surpass Homer in literature or Plato in philosophy. (In my opinion, our average intellectual level is clearly much lower and our educated public probably peaked in consciousness and morality between the 1840s and 1920s. Our much superior science and technology is of no import in this respect, we’ve simply acquired more means of being foolish, something which could well end in the extinction of our dear human race.)

Homer’s influence over the Greeks was like “that of the Bible and Shakespeare combined or to Hollywood plus television today” (29). (Surely another marker of our catastrophic moral and intellectual decline. Of course, in a healthy culture, audiovisual media like cinema and television would be propagating the highest values, including the epic tales of our Greek heritage, among the masses.)

Homer glorified love of honor (philotimo) and excellence (areté), a kind of individualism wholly unlike what we have come to know. This was a kind of competitive individualism in the service of the community. They did not glorify individual irresponsibility or fleeing one’s community (which, to some extent, is the American form of individualism). If the hoplite citizen-soldiers did not fight with perfect cohesion and discipline, then the city was lost.

Dominique Venner has argued [4] that Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey should again be studied and revered as the foundational “sacred texts” of European civilization. (I don’t think the Angela Merkels and the Hillary Clintons would last very long in a society educated in “love of honor” and “excellence.”)

Plato, often in the running for the greatest philosopher of all time, was an anti-democrat, arguing for the rule of an enlightened elite in the Republic and becoming only more authoritarian in his final work, the Laws. Athenian democracy’s chaos, defeat in war with Sparta, and execution of his mentor Socrates for thoughtcrime no doubt contributed to this. Karl Popper argued Plato, the founder of Western philosophy, paved the way for modern totalitarianism, including German National Socialism.

The Greek city-states were tiny by our standards: Sparta with 50,000, Athens 250,000. One can see how, in a town like Sparta, one could through daily ritual and various practices (e.g. all men eating and training together) achieve an incredible degree of social unity. (Of course, modern technology could allow us to achieve similar results today, as indeed the fascists attempted and to some extent succeeded.) Direct democracy was similarly only possible in a medium-sized city at most.

The notion of citizenship is something that we must retain from the Greeks, a notion of mutual obligation between state and citizen, of collective responsibility rather than the selfish tyranny of ethnic and plutocratic mafias. Rodgers argues that polis may be better translated as “citizen-state” rather than “city-state.” The polis sometimes had a rather deterritorialized notion of citizenship, emigrants still being citizens and in a sense accountable to the home city. This could be particularly useful in our current, globalizing age, when technology has so eliminated cultural and economic borders, and our people are so scattered and intermingled with foreigners across the globe.

The ancient Greeks are also a good benchmark for success and failure: Of repeated rises and falls before ultimate extinction, of successful unity in throwing off the yoke of the Persian Empire (with famous battles at Thermopylae and Marathon . . .), and of fratricidal warfare in the Peloponnesian War.

The sheer brutality of the ancient world, as with the past more generally, is difficult for us cosseted moderns to really grasp. Conquered cities often (though not always) faced the extermination of their men and the enslavement of their women and children (often making way for the victors’ settlers). Alexander the Great, world-conqueror and founder of a still-born Greco-Persian empire, was ruthless, with frequent preemptive murders, hostage-taking, the razing of entire cities, the crucifixion of thousands, etc. He seems the closest the Greeks have to a universalist. (Did Diogenes’ “cosmopolitanism” extend to non-Greeks?) The Greeks thought foreigners (“barbarians”) inferior, and Aristotle argued for their enslavement.

The Greeks’ downfall is of course relevant. The epic Spartans gradually declined into nothing due to infertility and, apparently, wealth inequality and female emancipation. Alexander left only a cultural mark in Asia upon natives who wholly failed to sustain the Hellenic heritage. One Indian work of astronomy noted: “Although the Yavanas [Greeks] are barbarians, the science of astronomy originated with them, for which they should be revered like gods.”

One rare trace of the Greeks in Asia is the wondrous Greco-Buddhist statues [5] created in their wake, of serene and haunting otherworldly beauty.

The Jews make a late appearance upon the scene, when the Seleucid Hellenic king Antiochus IV made a fateful faux pas in his subject state of Judea:

Not realizing that Jews were somehow different form his other Semitic subjects, Antiochus despoiled the Temple, installed a Syrian garrison and erected a temple to Olympian Zeus on the site. This was probably just part of his general Hellenizing programme. But the furious revolt that broke out, led by Judas Maccabeus the High Priest, finally drove the Seleucids from Judea for good. (241)

No comment.

There is wisdom: “Nothing in excess,” “Know thyself.”

So all that Alt Right propaganda using uplifting imagery from Greco-Roman statues and history, and films like Gladiator and 300, and so on, is both effective and completely justified.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

L’État-nation, dont la France est l’archétype, désire l’égalité, l’uniformité, la centralisation ; il établit une loi unique sur l’ensemble de son territoire. Il ne reconnaît pas la diversité des coutumes et tend à la suppression des différences locales. Il suppose que tous les peuples sous son empire adoptent les mêmes mœurs et s’expriment dans sa langue administrative.

L’État-nation, dont la France est l’archétype, désire l’égalité, l’uniformité, la centralisation ; il établit une loi unique sur l’ensemble de son territoire. Il ne reconnaît pas la diversité des coutumes et tend à la suppression des différences locales. Il suppose que tous les peuples sous son empire adoptent les mêmes mœurs et s’expriment dans sa langue administrative.