Political Theology of Juan Donoso Cortés

by Jacek Bartyzel

Ex: http://www.disenso.info

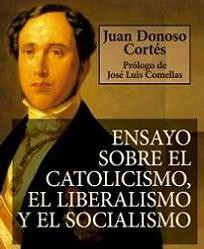

The term “political theology” has never been a more adequate definition of any corpus of thought[1] created by a philosopher, than when applied to the work of Spanish traditionalist Juan Donoso Cortés (1809-1853), who affected the social teachings of the Catholic Church (in statements of Blessed Pope Pius IX) in such a material way, that contemporary Catholic writer Rino Cammilleri is fully justified to call Cortés “the Father of the Syllabus”[2]. In the opinion of the author of Ensayo sobre el catolicismo, el liberalismo y el socialismo, considerados en sus principios fundamentales, theology is always at the foundation of any social issue, because if everything comes from God and if God is in everything, only theology is the skill which presents the final cause of all things; this explains why the knowledge of truth decreases in the world proportionately to the decreasing faith[3]. The sense of dependence of the fate of peoples on God’s providence is common to all eras and civilisations, and an opposite opinion – negating providentialism – should rather be considered as “eccentric.” A notable exception to this rule and an instance of theological “deafness” existing in the times of old was for Donoso the character of Pilate, who in the opinion of the theologian had to yield to Caiaphas precisely because he failed to understand the relationship between theology and politics. If Pilate had a “lay” concept of politics combined with brilliant mind, he would be only able to become instantly aware that he is not dealing with a political rebel who may pose direct threat to the state; however, as he did not consider Jesus guilty from the political point of view, he was also unable even to presuppose that the new religion might change also the world of politics.

The term “political theology” has never been a more adequate definition of any corpus of thought[1] created by a philosopher, than when applied to the work of Spanish traditionalist Juan Donoso Cortés (1809-1853), who affected the social teachings of the Catholic Church (in statements of Blessed Pope Pius IX) in such a material way, that contemporary Catholic writer Rino Cammilleri is fully justified to call Cortés “the Father of the Syllabus”[2]. In the opinion of the author of Ensayo sobre el catolicismo, el liberalismo y el socialismo, considerados en sus principios fundamentales, theology is always at the foundation of any social issue, because if everything comes from God and if God is in everything, only theology is the skill which presents the final cause of all things; this explains why the knowledge of truth decreases in the world proportionately to the decreasing faith[3]. The sense of dependence of the fate of peoples on God’s providence is common to all eras and civilisations, and an opposite opinion – negating providentialism – should rather be considered as “eccentric.” A notable exception to this rule and an instance of theological “deafness” existing in the times of old was for Donoso the character of Pilate, who in the opinion of the theologian had to yield to Caiaphas precisely because he failed to understand the relationship between theology and politics. If Pilate had a “lay” concept of politics combined with brilliant mind, he would be only able to become instantly aware that he is not dealing with a political rebel who may pose direct threat to the state; however, as he did not consider Jesus guilty from the political point of view, he was also unable even to presuppose that the new religion might change also the world of politics.

Donoso Cortés finds proofs of the dependence of political concepts on religious ones in the whole history of civilised communities, starting from the antinomy between the ancient East and West, represented by ancient Greece. Pantheism common in oriental despotic systems, condemned peoples to eternal slavery in huge but temporarily founded empires, while Greek polytheism created crowded republics of humans and gods, where gods – often delinquent, quarrelling and adulterous – were often human enough, while humans -heroic and talented in philosophy – carried divine characteristics. In contrast to the monotonously static character of Eastern civilisations, the Hellenic world borne various traces of beauty and movement, for which, however, it paid with political chaos and comminution. However, the synthesis of Eastern power and Greek dynamics combined in Rome, two-faced as Janus[4] , which disciplined all gods, forcing them to enter the Capitol, and also – by enclosing nations in its Empire – performed the providential work, preparing the world for evangelisation.

In the apologetic “prodrome” of his political theology, Donoso Cortés emphasises the fact that Christianity has transformed both the lay community (primarily the family in which the father – retaining the respect and love of his children – ceased to be a tyrant for his enslaved wife and children) and also the political community, transforming the pagan domination by force into the concept of power as public service to God: The kings began to rule in the name of God; nations began to obey their princes as guardians of power coming from God[5]. And, which is most important, by depriving the earthly rulers from the attribute of divinity, which they did not deserve, and on the other hand, by providing the divine authority to their rule, Christianity has once and for ever erased any excuse for both political manifestations of the sin of pride– the t y r a n n y of rulers and the r e v o l u t i o n of the subjects: By adding divine quality to the authority, Christianism made obedience holy, and the act of making authority divine and obedience holy condemned pride in its two most dire manifestations which are the spirit of tyranny and the spirit of rebellion. Tyranny and rebellion are impossible in a truly Christian community[6].

It is obvious for Donoso Cortés that Christianity would not be able to exert such beneficial influence, if the Catholic Church had not been an institution of supernatural origin, established by the God – Man himself, by Jesus Christ. Without the supernatural element, without the action of grace, one can perceive in civilisations only[7] the results and not causes, only elements which make up civilisations and not their sources. However, the Christian community differs absolutely from the ancient community, even with respect to politics and society, for the fact that in the ancient community people generally followed instincts and inclinations of the fallen nature, while (…) people in the Christian community, generally, more or less, died in their own nature and they follow, more or less the supernatural and divine attraction of grace[8]. This not only accounts for the superiority of political institutions of the Christian community over pagan ones, but also supports a thesis which is anthropological and soteriological at the same time and says that a pagan man is a figure belonging to pagan, disinherited humanity, while a Christian man is a figure of redeemed humanity. This thesis is simultaneously compatible with an ecclesiological thesis which says that the Church presents human nature as sinless, in the form in which it left God’s hands, full of primeval justice and sanctifying grace[9].

The apologetics of Donoso Cortés says in conclusion that the Church is not (as Guizot assumed) just not one of the many elements of European civilisation, but it is the very civilisation, as the Church gave this civilisation unity, which became its essence. European civilisation is simply Catholic civilisation. The Christianity (“the catholic dogma”) is a complete system of a civilisation, which embraces everything – the teaching about God, the teaching about the Universe and the teaching about man: Catholicism got the whole man in its possession, with his body, his heart and his soul[10].

Donoso Cortés expressed his conviction that political theology provides a sufficient explanation for everything, in a sentence which echoes with the opinions of Tertullian, the most anti-philosophic apologist of ancient Church: A child, whose mouth is feeding on the nourishing milk of Catholic theology, knows more about the most vital issues of life than Aristotle and Plato, the two stars of Athens[11]. This is not a coincidence if one considers that Donoso used to describe the lay, naturalist and rationalist Enlightenment trends against which he fought, as “philosophism”. However, the most vital consequence of such approach seems to be no need for a separate political theology which would be autonomous against the whole corpus of theology as such. Characteristically enough, it was Catholicism and not conservatism which was evoked in opposition to liberalism and socialism in the whole dissertation by Donoso, and not only in the heading of his opus magnum – and not only due to the fact that conservatism in Spain means the right wing of the liberal camp (moderados, or „the moderate”), and that the author of Ensayo… used to be one of the leaders of this camp before his spiritual transformation and that he radically disassociated himself from this camp after this transformation. If Donoso wished to illustrate the opposition of political doctrines, he could have used the term “traditionalism” which in Spain is commonly identified with the orthodox Catholic counter-revolutionary camp. However, the term „traditionalism” never appears in his work, which proves that it was not necessary for Donoso’s concepts; the fact that the author consistently follows the line of thought confronting Catholicism with liberalism and socialism proves that he aimed at counterpoising religion (and inherent political theology) against ideologies which are understood as “anti-theologies” or “false theologies.” This phenomenon discloses political a u g u s t i n i s m of Donoso, for whom the political authority is not vital, and it is justified only “for the reason of sin” (ratione peccati) of man, which is proved also by the theory of “two horse bits” explained elsewhere[12]; such bits are to curb sinful inclinations of humans. The first, spiritual bit is to appeal to conscience, while the other, a political one, is based on compulsion. The other bit is still necessary, in spite of the Redemption on the Golgotha as the Sacrifice of the Cross redeemed only the original sin but it did not erase the option of man’s continuing inclination towards the evil. For this reason, although the Good News has excluded compulsion as the sole option to be used, the political power must continue its existence to prevent depravation; what is more, its role and the choice of the tools of compulsion must grow, as the religion and morality are gradually weakening since the disruption of the medieval Christianitas. When the quicksilver on the “religious thermometer” is falling dramatically, the rise of quicksilver on the “political thermometer” seems to be the only means to prevent total fall and self-erasure of people.

Another Augustinian aspect of the political theology of Donoso Cortés is the fact, that it focuses on discussing the four cardinal issues of Christian theodicy in which the Bishop of Hippo was also considerably involved: 1º the secret of free will and human freedom; 2º the question on the origin of evil (unde malum?); 3º the secret of the heredity of the original sin and joint guilt and punishment; 4º the sense of blood and propitiatory offering.

The Theory of Freedom

Donoso Cortés discusses three aspects of freedom, seen as perfection, as means to achieve perfection and in the perspective of historia sacra – its history in Heavens and on earth, together with implications of its abuse by angels and humans.

Donoso Cortés discusses three aspects of freedom, seen as perfection, as means to achieve perfection and in the perspective of historia sacra – its history in Heavens and on earth, together with implications of its abuse by angels and humans.

First, the author rejects common opinion that the essence of free will is the option to choose between good and evil (resp. „freedom of choice”). Such situation would have two implications, which Donoso sees as irrational: firstly, the more perfect is man, the less freedom he has (gradual perfection excludes the attraction of evil), and hence a contradiction between perfection and freedom and secondly, the God would not be free as God cannot have two contradictory tendencies – towards good and towards evil. In the positive sense, freedom does not consist in the option to choose between the good and the evil, but it is simply the property of the rational will[13]. However, one must differentiate between perfect and partial freedom. The first one is identical with the perfection of mind and will and can be found only in God, and hence only God is perfectly free. Man, however, is imperfect, as every other created being and he is only relatively free. Which is more, the level of freedom available for man is directly proportionate to the level of his obedience towards the Maker: man grows in freedom when loves God and shows due respect to the God’s law, and when man departs from God and condemns God’s law, he falls under the rule of Satan and becomes his slave. This is the not only a crystallisation of Donoso’s concept of truth but also of his understanding of authority; freedom consists in the obedience to the authority of the Heavenly Ruler, while slavery is the obedience to the devilish “appropriator”. The link between the natural and supernatural order, identified by political theology, allows to determine by analogy, the earthly submission to a ruler legitimate by his obedience to God and the submission to a godless usurper.

The option to follow the evil, which is the “freedom of choice” is factual, but it is a mistake to consider it to be the essence of freedom; this is just an affection resulting from the imperfection of human will, and therefore it is a week and dangerous freedom which threatens with falling into the slavery of the “appropriator.” Free will, understood as the possibility to turn good into evil, is such a great gift, that, from God’s perspective, it seems to be a kind of abdication and not grace[14], and therefore it is a secret which is terrifying by the fact that man, making use of it, is just continually spoiling the God’s work. Therefore, everybody who cares for achieving true freedom – the freedom from sin – should rather attempt to put this option to sleep or even to lose it wholly if possible, which can be achieved only with the assistance of grace. Without grace, also resulting from acts, one can do nothing – one can only get lost. Grace which gives freedom from sin does not contradict freedom itself because it needs human participation in order to operate. According to fundamental theology, man is granted the grace sufficient to move the will by delicate pull; if man follows this, his will unites with God’s will and in this way the sufficient grace becomes effective. In the light of the above, the freedom of human will understood as the means leading to perfection is, the most wondrous of God’s wonders[15], as the man may resist God and get his dire victory while, in spite of this, God remains the winner and man remains the loser[16], losing his redemption. However, as long as the great theatre of the world[17] still stages the giant struggle between the “Two Cities” – Civitas Dei and the civitas terrena ruled by the Prince of This World, between the Divine and the Human Hercules, every man, consciously or unconsciously serves and fights in one of the armies and everybody will have to participate in the defeat or in the victory[18]of theMilitary Church (Ecclesia militans). The fight will cease in eternity, in the homeland of the righteous – the citizens of Ecclesia triumphans.

In the soteriological aspect, the weakness of human will is the “sheet anchor” for man, which explains the comparison of human and angelic condition. Angels were placed on the top of hierarchy of created beings, and received from the God a greater scope of freedom, which proved to have irrevocably disastrous effect on the angels which rebelled. Angels, more perfect than men, are granted a once-off act of choice only, so the fall of rebel angels was both immediate and the final, and their condemnation allowed no appeal. Man, weaker from angels with respect to his will and his mind, had for this very reason retained the chance for his redemption and the hope to be saved. The decisive damnation can be “earned” by man only when, the human offence, by repetition, reaches the dimension of the angelic offence[19].

Therefore, Donoso Cortés examines the question why God has not decided to “break” human freedom to save man, even against the “freedom of choice” which – as we know – is just an option for self-damnation? His answer allows to withdraw the suspicion of tendencies towards the Lutheran principle of justification sola gratia, as it emphasises the necessity of m e r i t s to be saved, as the lack of merits would be not adequate to the divine perfection. Redemption without merit would not be God’s goodness but His weakness, the effect without cause, something which we call on earth (…) a whim of a nervous woman[20].

The possibility of eternal damnation is only balanced by the possibility of redemption. The first one is God’s justice, the other – God’s grace. Donoso Cortés emphasises that the only consistent and logical option is either to accept or reject both options simultaneously as everything outside the common notion of “going to Hell” is not the true punishment, while everything outside “going to Heavens” is not the true reward: Cursing God for allowing the existence of Hell is the same as cursing God for creating Heaven. [21]

Freedom and Truth

Donoso Cortés’ theory of freedom incorporates one more vital motive, which is the discussion on the relationship of freedom and truth. Naturally, in his understanding, the Church is the depository of absolute truth, but such solution implies a very meaningful and painful paradox. The truth and beauty of the Catholic teaching do not by any means contribute to the popularity of the Church; the actual situation is just opposite: the world does not listen to this teaching and it crowds around the pulpits of error and carefully listens to wanton speeches by dirty sophists and miserable harlequins[22]. This gives rise to assumptions that the world is persecuting the Church not only because it forgot Its truth, holiness, the proofs of the divine mission and His miracles, but because the world abhors all these notions.

However if the Church, in spite of its losses and persecution, has survived two thousands years, where is the cause of its triumph, if not in the truth which it represents? The only cause is the supernatural force supporting the Church, the mysterious, supernatural right of grace and love. Donoso Cortés justifies this thesis with a paradoxical argument that Christ did not “win over the world” not with the truth, as Christ impersonates truth and the essence of that truth was already known in the Old Testament, but the people of the Old Covenant rejected the Impersonated Truth and crucified it on the Mount of Calvary: This is a dire lesson for those believing that truth, by its inherent force, may extend its reign and that the error cannot rule over the earth[23]. The Saviour won over the world, but not due to the fact that He is the world, but i n s p i t e o f t h e t r u t h !

The truth, by itself, cannot triumph exactly because of the freedom of man, whose mind and will are dimmed by the fall of sin. A man, in the fallen state, becomes the enemy of truth which he treats as the “tyranny” of God and when he crucifies God, he thinks that he has killed his tyrant.

The most extensive explanation for the secret of wrong choices made by human will is found by Donoso Cortés on the Gospel of St. John: I am come in my Father’s name, and ye receive me not; if another shall come in his own name, him ye will receive. (J, V, 43) According to Cortés, these words prove the natural triumph of the false over the true, of the evil over the good[24]. The natural tendency of fallen will towards evil is confirmed by the people of Jerusalem choosing Barabbas and by the inclination which contemporary proletariat displays towards false socialist theology. The Nature is unable to choose truth; one needs grace and love in order to choose truth, as no man can come to me, except the Father which hath sent me draw him. (J, VI, 44) Simply speaking, the triumph of the Cross is incomprehensible, as the victory of Christianity requires constant, supernatural activity of the Holy Spirit.

The assumption that man in his (fallen) natural state is the enemy of truth and that his “free choices”, stripped from the support granted by grace, must always be wrong, has extremely weighty implications. This means, that freedom cannot be trusted and the “right of choice” is always destructive, both in the state and in the Church. In the former, when people despise of the monarchy by God’s grace and believe in their “natural” right to choose leaders following their will, there is no other hope for maintaining order, than establishing d i c t a t o r s h i p perceived in an “occasionalist” sense, as an analogon of a miracle performed by God which suspends the “ordinary” rights of nature, albeit also established by themselves; in such circumstances, the dictatorship also proves the implementation of the divine right of love.[25]. However, on the ecclesiastic plane, the pessimistic assessment of human nature, which perfectly harmonises with the “spirit of the Syllabus”, discloses at the same time a basic discrepancy between Donoso Cortés together with dictates of the Syllabus (and the whole body of the traditional teaching of the Church on the issue), and an optimistic thesis which has been advocated since Vaticanum II, saying that “the truth wins in no other way than by the power of the truth itself”. Adoption of such thesis results in the resignation from the postulate of a Catholic state and proclaims the right of every person to “religious freedom” expressed in the declaration Dignitatis humanae and condemned in the Syllabus[26]. The traditional teachings of the Magisterium include innumerable examples of the same thesis[27] which Donoso presented in Ensayo…, saying that the error has no “right” by itself and that there can be no “freedom for the error” which is as abhorrent as the error itself[28]. This implies that the Church has the right to judge errors which, according to Donoso, protects one against relativism, which is an unavoidable consequence of catalogues of “agreed and arbitrary truths[29]being made by humans, and also implies beneficial character of intolerance which saved the world from chaos, putting above any discussion the truths which are holy and original, which provide the very foundation for any debate; truths, which cannot be doubted even for a moment, for this might instantly shake the mind unsure of truth or error, for his immediately dims the bright mirror of human mind[30]. Only the Church has the holy privilege of useful and fruitful debate, similarly as only the faith incessantly delivers truth and truth incessantly delivers knowledge[31], while doubts may deliver only further doubts.

Where did Evil Come From?

Erroneous interpretations of the key issue of theodicy on how to reconcile the imperfection of free human will with divine justice and goodness result, in the opinion of Donoso Cortés, from the very erroneous definition of freedom. A mind permeated with such definition is unable to explain to itself why God keeps yielding to the erroneous human will and He allows rebellion and anarchy on Earth. Terrified by this concept, such mind must resort to Manicheism – either in its traditional ancient form which advocates the existence of two gods (or equivalent principles): of good and evil, or in its modern form identified by Donoso with atheist and anthropolatric socialism of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. According to Donoso, any Manicheism is able to explain, in its own manner, the nature of fight and duality of the good and the evil but no Manicheism is able to explain the nature of peace and unity or convincingly prove any final victory, as this would require the annihilation of one or the other element, while any destruction of a putative substantial being is beyond comprehension. Only Catholicism provides a solution for this contradiction, as it explains everything by pointing out to an ontological difference between man and God which also serves as an explanation of the origin of evil, without the need to substantiate evil or to negate divine omnipotence or goodness[32].

Erroneous interpretations of the key issue of theodicy on how to reconcile the imperfection of free human will with divine justice and goodness result, in the opinion of Donoso Cortés, from the very erroneous definition of freedom. A mind permeated with such definition is unable to explain to itself why God keeps yielding to the erroneous human will and He allows rebellion and anarchy on Earth. Terrified by this concept, such mind must resort to Manicheism – either in its traditional ancient form which advocates the existence of two gods (or equivalent principles): of good and evil, or in its modern form identified by Donoso with atheist and anthropolatric socialism of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. According to Donoso, any Manicheism is able to explain, in its own manner, the nature of fight and duality of the good and the evil but no Manicheism is able to explain the nature of peace and unity or convincingly prove any final victory, as this would require the annihilation of one or the other element, while any destruction of a putative substantial being is beyond comprehension. Only Catholicism provides a solution for this contradiction, as it explains everything by pointing out to an ontological difference between man and God which also serves as an explanation of the origin of evil, without the need to substantiate evil or to negate divine omnipotence or goodness[32].

God, as the absolute Good, is the creator of every good. Therefore it is not possible for the God to create evil, because, although God cannot put in the Creation everything which exists in there, (…) he cannot put there anything which does not exist in Himself, and no god exists in God[33]. On the other hand, God cannot place absolute good in anything, because this would imply the creation of another God. Therefore, God grants to all the creation only relative good, something of what exist in Him, but which is not Himself[34]. If God is the Maker of everything, then the whole creation is relatively good, including Satan and Hell. Satan, choosing to become the being which he is, that is the Evil, did not lose his angelic nature, which is good, as it was created by the God.

Although all the created beings are good, the evil exists in the world and it wreaks dire havoc there. In order to solve this riddle, one must clarify three issues: where does evil come from, what is evil and how finally it is a factor of general harmony.

Evil finds its beginning in the way in which man (and earlier, the fallen angels) used the freedom of will, which was given to him and which is commonly called the “freedom of choice” between the good and the evil, which should be more adequately and precisely called the freedom to unify with the good which exists independently from man, that is with God, or the freedom to depart from God and to negate Him by such departure and to turn towards Evil which is nothingness. Therefore, the occurrence of evil is the result of double negation: negation of the mind, which results in error (negation of truth) and negation of the will which results in evil (negation of good). Both negations are at the same time an absolute negation of God as the truth and the good are substantially the God, that is the same thing which is just discussed from two different points of view.

This negation, naturally enough, does no harm to God, but it introduces disharmony in his Creation. Before the rebellion of angels and the fall of man, everything in the Creation (including matter), gravitated towards God, the truth and the good, while those two metaphysical rebellions resulted in disorder which consists in separating things which the God intended to unite and by uniting things which the God wished to separate. In other words, the gravitation towards God has been changed by rebelling angels and fallen men into the revolutionary movement centred on themselves; both the Satan and the man turned themselves into their absolute and final goal. The price for this “emancipation” was, however dreadful; for Satan, it was final damnation, but the man also paid a lot; with a disintegration of his mental and physical powers. Human mind lost its rule over the will, the will lost its power over actions, the body renounced allegiance to the spirit and the spirit became enslaved by the body.

Therefore, Donoso Cortés affirms, using the mighty power of his fiery rhetoric, the Catholic philosophical thesis derived from St. Augustine which considers that good is identical with the being and that the evils is not metaphysical. The evil “is” the non-existence; it does not exist substantially, it exists only qualitatively, as a manner of being and not as a substance. Therefore, the expression “evil” does not evoke any other notion than the notion of disorder, as the evil is not a thing but just a disorderly manner of existence of things, which did not cease to be good in their substance[35]. Evil is only accidental and as such it cannot be the work of God, but it can be – and is – the work of Satan and man. In the light of the thesis of non-substantiality of evil, which according to Donoso is the only one which is not internally contradictory, both the Manichean theology of “two gods” and the resulting thesis on the constant struggle between God and man become unreasonable. Such struggle is impossible because the man – the maker of accidental and transitory evil – is not equal to God, and consequently, no true struggle may take place where the victory is not possible (for the disproportion of power) and it is not fore-judged (being constant).

Elaborating on the issue of the reconciliation of the possibility of man’s committing evil with the omnipotence of the providential God’s will, Donoso Cortés says that this “terrible freedom” of disrupting the harmony and beauty of the Creation would not have been given to man by God if the God had not been sure that He would be able to turn it into the tool of His plans and to stop the devastation. The point is, that the separation between the Maker and his Creation, which is real in one (moral) respect, becomes feigned in another (existential ties of dependence). Originally – before the rebellion and the fall – rational and free beings were linked with God by the power of His grace. They separated themselves through sin, breaking the node of grace (and hence actually proving their freedom), but when they depart from the God by the power of their will, they approach Him in some other way, because they either encounter His justice or they become the object of His grace. In order to explain this phenomenon, Donoso evokes the medieval metaphor (known, among others, to Dante) which depicts the Creation as a wheel and the God as its circumference on one hand and its centre on the other. Being the centre, God attracts things to Himself, and as the circumference, He encloses. Created beings either gravitate towards the Maker being the circle, or they depart from Him, but then they encounter Him being the circumference, so they always are under God’s hand, wherever they go[36]. If one characterises man as a being which introduces disorder into order, then the divine character of God consists also in the ability to extract order from disorder, changing the temporary separation into unbreakable unity. Whoever is not willing to unite with Him through eternal rewards, shall be united by eternal punishment. The end (goal) which every creature is to reach has been chosen by the God; the creature may chose only the way – either towards damnation or towards salvation.

Elaborate rhetoric antinomies of Donoso Cortés include also a justification for God’s approval for the man’s offence, because the God had “the Saviour of the World, to be used as a kind of reserve[37]; this thesis was one of the reasons for which the author of Ensayo…. has been accused of heresy by father Gaduel, editor of „L`Ami de la Religion”. However, it seems extremely doubtful (also according to the Holy Officium to which Donoso appealed) for this sentence, saying: Man sinned, because God decided to become man[38], to be justifiably interpreted as considering God to be the reason for Adam’s sin, as such causality is negated by subsequent words: Man wavered, because God has the power to support; man fell, because God has the power to uphold[39].

Ideologies which are Negations

The concept of evil as non-existence and the concept of falsity as non-truth is applied by Donoso Cortés to confront Catholicism with ideologies of liberalism and socialism. Their falsity appears there as the lack of ontological and epistemological positivism, resulting from the failure to understand nature and the origin of evil Both the liberal and the socialist concept of evil is too strikingly inadequate to the reality, as they seek evil in places where it does not dwell and overlook its significant manifestations. Liberals see evil in the sphere of political institutions inherited from the ancestors, which primarily embrace Christian monarchy, while socialists say that evil dwells in public institutions – mostly in the family and in private ownership. From the (superficial) point of view of temporary game of power between political parties, this difference seems to be a significant one which affects the public existence; the goals of liberals may seems relatively moderate (replacing traditional monarchy with parliamentary democracy, which actually gives power to the addicts of “debating”), while the intentions of socialists attack the very foundations of the community and evoke also the opposition of liberals. However, in the light of theology and philosophical anthropology, this difference seems diminished to a large extent, even to the point of becoming insignificant, as both these schools – silently or overtly – reject the Catholic dogma on the fall of creation and on the original sin affecting human nature. Both liberals and socialists see man as essentially good – not in the sense of a nature created as good, but always and absolutely, while the evil is always institutional ; the only difference is that both schools name different institutions. However, in any case this means re-ontologisation of the evil and in this sense one can talk about the „Manicheism” of both ideologies.

A significant difference between liberalism and socialism concerns the degree to which they negate the truth concerning the origin of evil, advocated by Catholicism. Liberalism is inconsistent in this respect and, one may say, even timid: it is afraid to negate this truth in a resolute way and it regrets to renounce any principle (including this Catholic principle, which it only subjects to an “amputation” of all non-liberal notions, which actually make up the very essence of Catholicism). Liberalism praises political revolution and calls it liberating while it impugns social revolution, failing to notice that the former causes the latter: the balance between socialism and Catholicism sought by liberalism is absolutely impossible, and for this reason the (…) liberal school will finally have to abdicate, either in aid of socialists, or in aid of Catholics.[40].

The impotence of the “liberal school” is therefore caused by its lack of political theology and by its inability to consistently negate it; such negation is replaced by disputes, which are even assumedly barren and inconclusive. This school may rule only when the community is in decay; the moment of its domination is the transitory and volatile moment in which the world does not yet know whether to choose Barabbas or Jesus and when it wavers between dogmatic statement and total negation. At that moment, the community accepts the government of those, who are afraid to say: “I confirm” and those are equally afraid to say “I negate”so they always say “I differentiate”. The highest interests of this school consist in preventing the arrival of the day of resolute negations or the day of resolute confirmations. In order to prevent it, this school resorts to debating, which is the best way to the confusion of all concepts and to dissemination of scepticism. It understands very well that people, who constantly listen to sophists discussing for and against things, finally fail to know which is which and they ask whether it is true that the truth and the error, the sin and the virtue are opposite concepts or whether they rather are one and the same thing, just seen from different points of view?[41]. Liberalism, however, is condemned to defeat because the man has been created to act and the continuous debate does not agree with action, and therefore it is against human nature. Therefore a day is coming when the people, following their desires and feelings, shall crowd public squares and streets, resolutely choosing either Barabbas or Jesus and levelling the stand of sophists to the ground[42].

The greater “resoluteness” of socialism consists in the fact, that socialists draw two consistent conclusions from the hypothesis on the goodness of man: a conclusion on the perfection of man (which actually is deification of man) and the identification of evil with the God (or with the concept of God, which is the “threat to the conscience”). „The Golden Age” in socialist interpretation will flourish with the disappearance of faith in God, in the rule of mind over sense and the rule of governments over people; that is, when the brutal crowds will consider themselves as Gods, the law and the government[43]. Donoso Cortés sees this socialist system of the future as ideal despotism which combines pantheism of political, social and religious nature. This stands in express contrast with sociological individualism of Christianity which sees community as a group of humans obeying the same institutions and laws and living under their protection, while pantheists see community as an organism existing individually[44]. According to Donoso, this cardinal contradiction allows to perceive the logical consistency of Christian anthropology and the irrationality of socialist (collectivist) anthropology. If a community does not exist independently from people who are its members, then, naturally, a community can have no thing which did not originally exist in the individuals[45], and, logically enough, the evil and the good in a community originates from man and that it would be absurd to consider uprooting evil from a community without touching people in which the evil resides, being its source[46]. The concept of a holistically perceived community gives rise only to contradictions and unclear notions, which by themselves unmask socialism as a “charlatan” theory. It is not known, whether the evil in a community is substantial (in such situation, even an intention to destroy the existing social order would not be radical enough, as the full eradication of evil would be possible only after eradicating the community), or whether it is accidental; if the latter is true, what circumstances and reasons combined to give rise for this fatal coincidence? Unable to solve these contradictions, socialism leads to ascribe to man (a collective man) the name of the redeemer of community, and hence it advocates the same two secrets as Catholicism does (the secret of the origin of evil and the secret of redemption) but it only reverses them in a perverse way; the Catholicism says two simple and natural things: man is man and his doings are human while God is God and his doings are divine, then socialism says two things which are incomprehensible: that man undertakes and performs God’s works and the society performs acts appropriate to man[47]. With the consideration to the above, Donoso amends his earlier opinion on the logical advantage of socialism over liberalism, as socialism is “stronger” only by the way in which it advocates its issues, by its “theological” impetus, while the contents of the socialist doctrine is a monstrous conglomerate (…) of fantastic and false hypotheses[48].

Finally, if liberalism which emphasises its “neutral” lay character, is just an a n t i – t h e o l o g y, then, according to Donoso Cortés, socialism is a f a l s e t h e o l o g y, which is just an awkward plagiarism of the Gospel, an irrational “half-Catholicism” which creates a new “God” of a collective man. however, basically both these ideologies shine with the “moonshine” of Christianity, which consists in undermining Catholicism to various degrees and in various places and in misinterpreting the World of God.: In spite of being schools which directly oppose Catholicism, that is schools which would resolutely negate all the catholic statements and all the principles, they are schools which just differ from Catholicism to a larger or smaller degree; they have borrowed from Catholicism everything which is just not a pure negation and they only live its life[49]. The author of Ensayo… is of the opinion that all heresiarchs, including political ones, share the common fate, as when they imagine that they live outside Catholicism, they actually live within, because Catholicism is just as the atmosphere of minds; socialists follow the same fate: after huge efforts aimed at the separation from Catholicism they have just reached the condition of being bad Catholics[50].

The Heredity of Sin

A theodicy would be incomplete if it failed to complement the answer to the question on the source and nature of evil with an explanation on the dogma of the heredity of original sin by all the generations. Donoso Cortés, who devoted the whole third chapter of his Ensayo… to discussing this issue, does not deny that this dogma in particular, being a dogma without which Catholicism would lose the reason for its existence – causes the highest “outrage” both for the purely natural justice and for the modern mentality, with its most expressive manifestations being the ideologies of liberalism and socialism. How can one be a sinner if he has not sinned, just at the moment of birth? On what grounds one may discuss the inheritance of Adam’s sin, which is the unavoidable consequence of that sin in the form of punishment, but without personal guilt? All this seems to fly in the face of all reason and the sense of the right, and to contradict the truth on the inexhaustible God’s grace advocated by the Christian religion. Instead, one might consider this dogma to be a borrowing from gloomy religions of ancient East, whose gods thrived on the suffering of victims and the sight of blood.

Although this question is usually posed on the ethical plane, the reply provided by Donoso Cortés transcends onto the ontological level, as he explains the putative contradiction between the absence of personal guilt and the heredity of sin and responsibility arising therefrom, with the duality of the existential structure of man. Our forefather Adam was at the same time an individual and mankind, and sin was committed before the separation of individual and mankind (by progeniture). Therefore, Adam sinned in both his natures: the collective and the individual one. Although the individual Adam died, the collective Adam lives on, and he has stored his sin in the course of life: the collective Adam and the human nature are the same thing; hence, human nature continues to be guilty, as it continues to be sinful[51]. Every man who comes to this world is a sinner, because he has human nature and human nature has been polluted: I sinned when I was Adam, both when mature, when I got the name which I carry, and before I came to the world. I was in Adam when he left the hands of God and Adam was in me when I left the womb of my mother; I am unable to separate myself from his person and unable to separate myself from his sin[52].

Every human being simultaneously upholds the individual element, which is its substantial personal unity, and an element which is common for the whole mankind. The first element, received by everyone from his parents, is just an accidental form of being; the other one, received (through Adam) from God , is the essence of every human being and this very fact is decisive for everyone’s participation in the sin. Individual sins are just “extras” added to the original sin which was at the same time one and common, exceptional and embracing nuclei of all sins. No man has been and will be able to sin individually in the same way as Adam: we just cover dirty spots with more dirty spots; only Adam soiled the snow-white purity[53].

Therefore one should note that the theory of existence of Donoso Cortés not only excludes idealistic ontologism, but on the other hand it also rejects nominalism, which denies the reality of the commoners (in this instance: the mankind). The result of the dogma of original sin and the rule of substantial unity of mankind is the dogma of the heaviness of the double responsibility of man (collective one concerning the original sin and the individual one concerning the sinful acts), which is the s o l i d a r i t y in sin. Only this solidarity gives to man his dignity, extending his life to cover the long course of times and spaces, and therefore, after a certain fashion, it gives rise to “mankind”: This word, meaningless for the ancients, only with the rise of Christianity began to express the substantial unity of human nature, the close kinship which unites all men in one family[54].

The heritage of guilt and punishment – and hence, without doubt, the suffering, should not be seen as evil, but only as good, available in the condition resulting from the irreversible fact of man’s depravity. If not for the punishment – which is in its essence a healing aid – the pollution would be irreversible and God would not have any means to reach man (to whom He gave freedom) with His grace. By rejecting punishment, we erase also the option of redemption. Punishment is just the very chance for being saved, denied to fallen angels, which ties a new bond between the Maker and the man. This punishment, although it still is relatively bad , being suffering, becomes the great benefit due to its purpose, which is the purification of the sinner: Because sin is common, the purification is also absolutely necessary for everyone; hence the suffering must also be common, if the whole mankind is to be purified in its mysterious waters[55].

Moreover, the dogma of solidarity also has its feedback aspect; solidarity remains in sin and in merit; if all people sinned with Adam, then all people were redeemed by Jesus Christ, whose merit is pointing towards them.

Social Implications of the Solidarity Dogma

According to Donoso Cortés, the concepts of heredity through blood and solidarity in sin explain all significant family, social and political institutions of mankind. If, for instance, a nation is well aware of the idea of hereditary transfer, its institutions will necessarily be based on heredity, and hence on stricte a r i s t o c r a t i c, basis, moderated, however, by things which are common (in solidarity ) to all people in a society and hence are democratic, but only in this very sense. This also refers to the democracy of Athens, which was nothing else than an aristocracy, impudent and anxious, serviced by a crowd of slaves[56].

However, the concept of solidarity was disastrous for pagan communities due to its incompleteness; particular phenomena of solidarity (in family, community and politics) were not moderated by human solidarity which is comprehensible only in the light of the Christian dogma. This resulted in the tyranny of husbands and fathers in the family, the tyranny of state over communities and the permanent and common state of war between states, as well as a twisted concept of patriotism as declaring war against the whole mankind by a caste which constituted itself as a nation[57]. In modern times, all disorder is caused by the departure from the “Christian dogma” which has already been made known..

Both the instances of crippled solidarity in pre-Christian communities and the denial of solidarity in “post-Christian” communities[58] – are proofs of the lack of elementary balance in all doings of man which remain only human. They show the impotence and vanity of man as compared with the might and perfection of God, who is the only one to be able to uphold everything, not degrading anything; on the other hand man, upholding anything, degrades all things which are not upheld by him: in the sphere of religion, he cannot uphold himself without degrading God at the same time; he can neither uphold God without degrading himself; in politics he cannot give homage to freedom without offending authority at the same time; in social issues he either sacrifices community to individuals or individuals to the community[59]. Due to this one-sidedness, Donoso Cortés describes both liberals and socialists as parties of equilibrists.

Both the instances of crippled solidarity in pre-Christian communities and the denial of solidarity in “post-Christian” communities[58] – are proofs of the lack of elementary balance in all doings of man which remain only human. They show the impotence and vanity of man as compared with the might and perfection of God, who is the only one to be able to uphold everything, not degrading anything; on the other hand man, upholding anything, degrades all things which are not upheld by him: in the sphere of religion, he cannot uphold himself without degrading God at the same time; he can neither uphold God without degrading himself; in politics he cannot give homage to freedom without offending authority at the same time; in social issues he either sacrifices community to individuals or individuals to the community[59]. Due to this one-sidedness, Donoso Cortés describes both liberals and socialists as parties of equilibrists.

Liberalism denies solidarity in the religious order, as both its ontological nominalism and its ethical meliorism do not allow it to accept the heredity of punishment and guilt. In turn, liberalism in the social order – as the follower of pagan egoism – denies the solidarity of nations, calling other nations strangers and it has not yet called them enemies only because it lacks enough energy[60].

Socialism goes even further, as it not only denies religious solidarity, heredity of punishment and guilt, but it also rejects the very punishment and guilt. The denial of the rule of heredity results therefore in the egalitarian principle of legal entitlement of everybody to all offices and all dignities[61] while egalitarianism gives ground to the denial of the diversity and solidarity of social groups which leads to the postulate of eradicating family and furthermore to the eradication of private ownership, with particular reference to land. This sequence of denials has a logic of its own, as one cannot understand ownership without some sort of proportion between the owner and his thing; while there is no proportion between land (Earth) and man[62]. The land does not die, and hence a mortal being cannot “own” it if one resigns from the notion of heredity. Purely individual ownership denies reason and the institution of ownership is absurd without the institution of family[63].

Socialism does not end with the denial of sin, guilt and punishment, but continuing the sequence of denials, it negates the unity and personality of man; in the result of rejecting tradition and historic continuity, socialism is unable to unite the present human existence with the past and the future, and all this leads it to unavoidable and total nihilism: Those, who tear themselves away from God go to nothingness and it cannot be the other way, as outside God there can be nothing but nothingness[64].

The Sense of Blood Offering

The “Cortesian” theodicy is crowned by the discussion on the necessity and sense of the propitiatory offering of blood – the most common procedure which is known almost to all religions, but is simultaneously the most mysterious and seemingly repulsive and irrational one.

The first blood offering was made by Abel – and, which is strange, God welcomed it just because it was the offering of blood, in contrast to the offering made by Cain, which was bloodless. It is even more puzzling that Abel, who spills blood for propitiatory offering, abhors the very fact of spilling blood and he dies because he refuses to shed blood of his envious brother, while Cain, who refuses a blood sacrifice to satisfy God, is fond of bloodshed to the point of killing his brother. This series of paradoxes leads Donoso Cortés to conclude that bloodshed functions as purification or erasure procedure, respectively to its purpose. Having discovered this, the fair Abel and Cain the fratricide become pre-figurations of the “Two States” which, according to St. Augustine, will struggle with each other until the end of history: Abel and Cain are the characters representing those two cities governed by opposite laws and by hostile lords; one of which is called the City of God and the other is the city of world and they are warring with each other not because one sheds blood and the other never does it, but because in the former, blood is shed by love while in the latter it is shed by vengeance; in the latter , blood is a gift to man to satisfy his passion, while in the former it is a gift to God for His propitiation[65].

Why everybody then sheds blood, in one way or another? According to Donoso, bloodshed is the inherent result of Adam’s misdeed. But, in the result of the promise of Redemption, by replacing the guilty person with the Redeemer, the death sentence has been suspended until His arrival. On the other hand, Abel, the heir of the death sentence and of the promise suspending it – is a memorial and symbolic offering. His offering is so perfect, that it expresses all the Catholic dogmas: as an offering in general, it constitutes an act of gratitude and respect for God; as a blood offering, it announces the dogma of original sin, heredity of guilt, punishment and solidarity, and also functions as reminder of the promise and the reciprocity of the Redeemer; finally, it symbolises the true offering of the Lamb without blemish.

However, in the course of generations, the original revelation, together with the message carried by Abel’s offering, became blurred, because simultaneously all men inherited the original sin, which corrupted human mind. The most deformed, cruel and fearful consequence of the misperception of the sense and purpose of blood offering was turning it actually into the act of offering human lives.

Where did pre-Christian peoples commit an error? This very fragment of discussion allows the reader experience the fine rhetoric by Donoso Cortés, his subtle reasoning and the sophisticated discourse. The discourse consists of a series of rhetoric questions (starting with anaphors) which are every time answered with a negative reply, except for the last question. Were the ancients wrong, thinking that divine justice needs propitiation? No, they were not. Were they wrong thinking that propitiation can be achieved only by bloodshed? No, they were not. Is it wrong that one person can offer enough propitiation to erase sins of everyone else? No, this is true. Or perhaps they were wrong thinking that the sacrificed one must be innocent? No, this was not false either. Their one and only error – which, however, had monstrous consequences – was the conviction that any man can serve as such (effective) offering. This one and only error, this single departure from the “Catholic dogma”, turned the world into the sea of blood[66]. This leads to the conclusion, which according to Donoso, remains ever true, that whenever people lose any Christian quality, wild and bloody barbarous behaviour is imminent.

The pagan error concerning offerings of blood was in fact only partial, because human blood is only unable to erase the original sin, while it can erase personal sins. This gives not only the justification but even the (…) necessity of death penalty[67], which was considered efficient by all civilisations, and those advocating its abolishment will soon see how expensive are such experiments, when blood immediately begins to seep through all its [community's – J.B.] pores[68]. Donoso Cortés saw the support of abolitionism as tolerance for crime which can be explained only by weakening religious spirit. It would be hard to say that his discussion on the subject lacks psychological sharpness and prophetic value: The criminal has undergone a gradual transformation in human eyes; those abhorred by our fathers are only pitied by their sons; the criminal has even lost his name – he became just a madman or a fool. Modern rationalists adorn crime with the name of misfortune; if this notion spreads, then some day communities will go under the rule of those misfortunate and then innocence will become crime. Liberal schools will be replaced with socialists with their teaching on holy revolutions and heroic crimes; and this will not be the end yet: the distant horizons are lit with even more bloody aurora. Perhaps some galley slaves are now writing a new gospel for the world. And if the world is forced to accept these new apostles and its gospel, it will truly deserve such fate[69].

The pagan error concerning offerings of blood was in fact only partial, because human blood is only unable to erase the original sin, while it can erase personal sins. This gives not only the justification but even the (…) necessity of death penalty[67], which was considered efficient by all civilisations, and those advocating its abolishment will soon see how expensive are such experiments, when blood immediately begins to seep through all its [community's – J.B.] pores[68]. Donoso Cortés saw the support of abolitionism as tolerance for crime which can be explained only by weakening religious spirit. It would be hard to say that his discussion on the subject lacks psychological sharpness and prophetic value: The criminal has undergone a gradual transformation in human eyes; those abhorred by our fathers are only pitied by their sons; the criminal has even lost his name – he became just a madman or a fool. Modern rationalists adorn crime with the name of misfortune; if this notion spreads, then some day communities will go under the rule of those misfortunate and then innocence will become crime. Liberal schools will be replaced with socialists with their teaching on holy revolutions and heroic crimes; and this will not be the end yet: the distant horizons are lit with even more bloody aurora. Perhaps some galley slaves are now writing a new gospel for the world. And if the world is forced to accept these new apostles and its gospel, it will truly deserve such fate[69].

Dignitatis humanae?

If human nature is so direly hurt by the fall of sin, and consequently the man may only add more errors to the first and main one, then how will it be possible to achieve at any time in the future the reinstatement of man’s unity with God? Donoso Cortés admits, that without solving this “dogma of dogmas” the whole Catholic structure (…) must fall down in ruin; as it has no vault[70]; in such instance, this structure would be just a philosophical system, less imperfect than the other ones.

This dilemma can be solved in one way only: by acknowledging the infinite l o v e of God for his Creation. Love is the only adequate description for God: God is love and love only. (…) We are all redeemed in love and by love[71]. The depth of human fall implies that the reconstruction of the order had to be achieved in no other way than through raising man to divinity which, in turn, had to be effected only by the Incorporation of the World, when God, becoming a Man, never ceased to be the God[72]. The Holiest Blood, spilt at the Calvary, not only erased Adam’s guilt but it also put the redeemed man in the state of merit.

This truly abysmal disproportion between the impotence of the fallen man and the immeasurable, freely granted God’s grace and love makes Donoso Cortés draw conclusions of utmost importance and far-reaching – in the opinion of some, too far-reaching – implications. The Secret of Incorporation is in his eyes, the only title of nobility for mankind, and therefore, whenever the author sees a man fallen by his own guilt and stripped from the sanctifying grace, the he is surprised by the restraint shown by rationalists in their contempt of man and he is unable to understand this moderation in contempt[73]. In this context, Donoso placed his most famous and most controversial statement: if God had not accepted human nature and had not elevated it to His level, leaving it with the shiny trace of His divinity, (…) man’s language would lace words to express human lowliness. As to myself, I can only say that if my God had not became a body in a woman’s womb and if He had not died on the cross for the whole mankind, then the reptile, which I trample with my foot, would have been less deserving of contempt in my eyes, than the whole mankind[74].

In other words, the common character of guilt does not only mean that grace is necessary for salvation and that no man can be considered to be “good by his nature”, which is unquestionable from the point of view of Catholic doctrine, but also refuses natural dignity to man in this state[75]. The author of Ensayo… admits openly: Out of all the statements of faith, my mind has the most difficulty to accept the teaching on the dignity of mankind – the dignity which I desire to understand and which I cannot see[76]. Various deeds of numerous famous people, extolled as heroic, seem to Donoso to be rather heroic misdeeds committed out of blind pride or mad ambition. It would be easy to understand what puzzlement or even horror would Donoso experience learning that Fathers of the Second Vatican Council promulgated the Declaration on Religious Freedom Dignitatis humanae, or perhaps he would think that the anthropological hyper-optimism which permeates this text proved that the heresy of naturalistic Pelagianism, contended by St. Augustine, has been reborn after 1500 years.

On the other hand, the ultra-pessimism of Donoso Cortés has exposed him to the accusations of antithetic heresy. His contemporary critic father Gaduel has discovered in Donoso’s statement on human dignity the condemned error of „baianism”, that is a thesis proposed by Michael Baius[77] saying that “all acts non resulting from faith are sinful” (omnia opera infidelium sunt peccata). However, this seems doubtful, as the author of Ensayo… does not offer any general statements, but discusses only a certain class of acts which are seen as good in the eyes of the “world”.

Father Gaduel is supported by Carl Schmitt, a Catholic, who, although fascinated by the decisionist thought of Donoso Cortés, considered the outbreaks of “monstrous pessimism” (and doubt in the chances to conquer evil, which “often is close to madness”[78]) demonstrated by the Spanish thinker to be a “radical form” of the concept of the original sin which departs from the “explanation adopted by the Council of Trent (…) which says, in contrast to Luther, that human nature has not been wholly polluted but it is only blurred by the original sin, has been hurt to a certain extent, but man still remains naturally able to do good”[79]. Schmitt says also that the way in which Donoso understands the original sin dogma “seems to overlap the Lutheran approach”, although he remarks that Donoso „would never accept Luther’s opinion that one should obey every authority”[80]. He also ventures to offer a peculiar defence of Donoso, emphasising that “he did not aim (…) at developing some new interpretation for the dogma, but to solve a religious and political conflict”, „ and therefore, when he says that man is evil by his nature, he primarily involves himself in polemics with atheist anarchism and its basic axiom – the natural goodness of man; his approach is hence polemic and not doctrinal”[81]. Such defence line would certainly never satisfy Donoso, who, truly enough, was very far away from the intention to develop a new interpretation for the dogma, but at the same time considered the compliance of his own opinions with the interpretation of the Magisterium as the issue of utmost importance.

The problem of whether Donoso Cortés has passed over the boundaries of orthodoxy at that moment, will probably remain controversial. One should remember however, that this would be only a “material” and not “formal” heresy, as Vatican has dismissed charges against him, and the defendant had in advance promised to submit himself to any decision.. In addition to that, even if Donoso was in fact too pessimistic about human nature, the same objection could be directed towards to late anti-Pelagian writings by St. Augustine, which has been disclosed by the controversy on Lutheranism and Jansenism[82].

The issues which, however, seem to remain beyond any essential controversy are the political implications of the anthropological pessimism of Donoso Cortés. This pessimism results in unambiguous rejection of a system based on the trust in human mind and goodness, which is the democratic system: I perceive mankind as an immense crowd crawling at the feet of the heroes whom it considers gods, while such heroes, similarly to gods, can only worship themselves. I could believe in the dignity of those dumb crowds only when God revealed it to me[83]. According to Donoso, any attempt at building a system based on the trust in human goodness and mind, is both heresy and madness. Only Jesus Christ can be the Master and the Focus of everything, both in the whole Creation and in a human state. Only in Him can reign the true peace and brotherhood, while the negation of his Social Kingdom brings only the division into parties, rebellions, wars and revolutions: the poor rise against the rich, the unhappy against the happy, the aristocrats against kings, lower classes against higher ones (…); the crowds of people, propelled by the fury of wild passions unite in their fight, just as streams swollen with rainstorm waters unite when falling into the abyss[84]. One of the best experts on Spanish traditionalist thought Frederick D. Wilhelmsen presents this ideal of the Catholic state in a nutshell, rightly saying that “the political authority in a well arranged society is just a manner of governing, which is always, although in diverse ways, subordinated to God. This means that authority, power and sovereignty can be united only in God”[85].

by Jacek Bartyzel

“Organon”, Instituto de Historia de Ciencia, Academia de Ciencias de Polonia, núm. 34/2006, págs. 195-216.

[1] Actually, this concerns the ideas of Donoso Cortés expressed after his religious transformation in 1843 when he changed from a moderate liberal and a “sentimental” Catholic into a determined reactionary and ultramontanist; I have discussed this evolution in more detail in my essay: Posępny markiz de Valdegamas. Życie, myśl i dziedzictwo Juana Donoso Cortésa, in „Umierać, ale powoli!”. O monarchistycznej i katolickiej kontrrewolucji w krajach romańskich 1815-2000, Kraków 2002, p. 351-387. See also Carl Schmitt: „For [Donoso] Cortés, his postulate of radical spiritualism is already equivalent to taking the side of a specific theology of struggle against an opponent. (…) … systemic discussion shows his effort to present in brief issues belonging to the good, old , dogmatic theology” – id., Teologia polityczna i inne pisma, selected, translated and prefaced by M. A. Cichocki, Kraków – Warszawa 2000, p. 80.

[2] See R. Cammilleri, Juan Donoso Cortés – Il Padre del Sillabo, Milano 1998, 2000².

[3] Jan Donoso Cortés, „Przegląd Katolicki” 1870, No.46, p. 724 [I quote all fragments from the Esej o katolicyzmie, liberalizmie i socjalizmie from this text (signed in the recent issue as Ks. M. N.) printed therein in the years 1870-1871, which is an actual translation (certainly from French) covering approximately 80 % of the original text and summarising the rest, with additional comments and a biographic sketch. However, I introduce corrections to this translation in places which depart from the meaning of the original or which sound too archaic (I have also modified spelling and punctuation), comparing it with contemporary Spanish edition of the text in Obras Completas, Madrid 1970, t. II, as well as with the French edition of Cortés' works edited by his friend, Louisa Veuillot – Œuvres de Donoso Cortés, marquis de Valdegamas, Paris 1858, t. III: Essai sur le catholicisme, le libéralisme et le socialisme considérés dans leurs principes fondamentaux].

[5] Ibid., „Przegląd Katolicki” 1870, No.49, p. 770.

[7] Similarly to François Guizot, a writer highly appreciated by Donoso, who however pointed out to his weaknesses and limitations resulting from his liberal, protestant and naturalist research perspective.

[8] Jan Donoso Cortés , „Przegląd Katolicki” 1870, No.52, p. 818.

[9] Ibid., „Przegląd Katolicki” 1870, No.49, p. 772.

[12] See J. Donoso Cortés, Carta al director de la „Revue de Deux Mondes”, [in:] id., Obras Completas, Madrid 1970, t. II [Polish translation of the fragment in: „Przegląd Poznański” 1849, t. VIII, p. 438-440].

[13] Jan Donoso Cortés „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No.1, p. 2.

[14] Ibid., „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No.4, p. 49.

[15] Ibid., „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No.1, p. 1.

[17] It is not a coincidence that Spaniard Donoso Cortés presents this Augustinian opposition of the Two Cities using a Baroque metaphor of el Gran Teatro del Mundo created by his great fellow countryman Pedro Calderón de la Barca.

[18] Jan Donoso Cortés, „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No.4, p. 51.

[19] Ibid., „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No.1, p. 6.

[22] Ibid., „Przegląd Katolicki” 1870, No.52, p. 818.

[23] Ibid., „Przegląd Katolicki” 1870, No.50, p. 786.

[25] See J. Donoso Cortés, Discurso sobre la dictadura, [w:] id., Obras Completas, Madrid 1970, t. II, p. 316 i n.

[26] See the condemned thesis XV: „Every man has the right to accept and believe in a religion which he has considered true, guided by the light of his mind” – Syllabus errorum, in: Bl. Pius IX, Quanta cura. Syllabus errorum. (O błędach modernizmu), Warszawa 2002, p. 23.

[27] For instance, Pius VII says that the public law, sanctioning equal freedom for the truth and the error, commits a “tragic and always contemptible heresy” (Post tam diuturnitas), Gregory XVI – „ravings” (Mirari vos), bl. Pius IX – „monstrous error” (Qui pluribus), which is most harmful to the Church and the salvation of souls” (Quanta cura), something which “leads to easier depravation of morals and minds” and to the “popularisation of the principle of indifferentism” (Syllabus), Leon XIII – „the public crime” (Immortale Dei), something which is “equivalent to atheism” (ibid.) and „contrary to reason”; quoted from: F. K. Stehlin, W obronie Prawdy Katolickiej. Dzieło arcybiskupa Lefebvre, Warszawa 2001, p. 188-189.

[28] Jan Donoso Cortés, „Przegląd Katolicki” 1870, No.49, p. 772.

[32] This explanation naturally repeats anti-Manichean polemics of St. Augustine, while the conclusions concerning modern (socialist) “Manicheisms” are his own.

[33] Jan Donoso Cortés, „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No.4, p. 52.

[36] Ibid., „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No.5, p. 66.

[40] Ibid., „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No.12, p. 179.

[45] The defence of this point of view allows to identify Donoso also as an Aristotelian, as he considers individual substances also as real beings.

[46] Jan Donoso Cortés, „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No.12, p. 181.

[50] Ibid., „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No.16, p. 245.

[51] Ibid., „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No.13, p. 195.

[54] Ibid., „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No.15, p. 226.

[55] Ibid., „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No.14, p. 210.

[56] Ibid., „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No.15, p. 227.

[58] This term has been, naturally unknown to the author of Ensayo…, but it stands with full compliance with his perception of the current condition of the society.

[59] Jan Donoso Cortés, „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No.15, p. 226.

[60] Ibid., p. 228 [Such characteristics of liberalism, which seems to fit rather nationalism, must seem surprising in modern times. However, the concept of Donoso can be defended, if one becomes aware that liberal doctrines and movements of his times - during the period of Romanticism - had a very strong national component, which in certain instances (Jacobinism, Italian Risorgimento), seemed just chauvinistic. Liberalism radically separated itself from romantic (proto)nationalism only at the end of the 19th century, a long time after the death of Donoso. It is also worth remembering that the concept of "holy egoism" (sacro egoismo), apparently Machiavellian in its spirit, and signifying the superior directive of a national state, has been born in the very circle of the liberal destra storica].

[62] Ibid., „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No.16, p. 241.

[65] Ibid., „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No.17, p. 259.

[70] Ibid., „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No.18, p. 274.

[72] Donoso’s use of Hegelian concepts such as “the synthetic union” of man with God (ibid., p. 277), or the “unification of ideality with reality” in the Son of God (ibid., p. 289) is well understandable in the historic context, although it introduces certain conceptual chaos to basically classical (mostly Augustinian and partly Thomistic) philosophical vocabulary of the Spanish theologian.

[73] Jan Donoso Cortés, „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No.18, p. 275.

[75] Terminology of traditional fundamental theology refers to the so-called “original dignity” with which man was supplied in the act of creation, in contrast to the “final dignity” which is inseparable form the strive towards truth, which has been reinstated in man by the act of Redemption.

[76] Jan Donoso Cortés, „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No.18, p. 275.

[77] For reference to the condemnation of 79 theses by Baius by St. Pope Pius V in 1567 see.: Breviarium fidei. Wybór doktrynalnych wypowiedzi Kościoła, edit.. S. Głowa SJ and I. Bieda SJ, Poznań 1989, p. 203-205.

[78] C. Schmitt, op. cit., p. 77.

[79] Ibid., p. 76 [In fact, Schmitt does not give an accurate brief of the Trent teachings; certainly, none of the canons of the Decree on the Original Sin, adopted at Session V in 1546 includes no statement that "man continues to be able to do good out of his nature.” Fathers of the Tridentinum consciously refrained from solving all problems related to the nature of the original sin and its effects, but they only rejected the teachings of Protestant reformers by declaring that the grace granted at baptism „effaces the guilt of original sin" and remits everything which "has the true and proper character of sin" and not only "blurs it or makes it no more considered as guilt” (Can. 5), quot. from: Breviarium fidei..., p. 202].

[82] See also.: L. Kołakowski, God Owes Us Nothing: A Brief Remark on Pascal’s Religion and on the Spirit of Jansenism, The University of Chicago Press 1995.

[83] Juan Donoso Cortés, „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No. 18, p. 276 [This perception of democracy has been repeated in an equally sarcastic, albeit lay form, by H.L. Mencken saying that “democracy is the cult of jackals professed by asses”.]

[84] Ibid., „Przegląd Katolicki” 1871, No. 19, p. 292.

[85] F. D. Wilhelmsen, Donoso Cortés and the Meaning of Political Power, [in:] Christianity and Political Philosophy, Athens 1978, p. 139, quot. from: M. Ayuso, La cabeza de la Gorgona. De la «Hybris» del poder al totalitarismo moderno, Buenos Aires 2001, p. 24.

De nos jours, la « discussion » est devenue une marchandise, le produit vendable des nouvelles par câble et des revues d’opinion; il n’y a plus même le prétexte d’une « recherche de la vérité ».

De nos jours, la « discussion » est devenue une marchandise, le produit vendable des nouvelles par câble et des revues d’opinion; il n’y a plus même le prétexte d’une « recherche de la vérité ». Nous voyons, cependant, que la négociation ne bouge que dans une seule direction. Par exemple, supposons que j’offre 50 $ pour un produit et que le vendeur demande 100 $. Nous négocions pour 75 $. Le vendeur connaît alors ma limite. Donc la prochaine fois que nous négocions, nous commençons à 75 $ et il exige 125 $. Si, par indécision, ou si je manque de volonté pour tenir ferme, vous pouvez voir que le prix va continuer à augmenter. Ainsi, les conflits sociaux continuent d’être résolus dans un seul sens, malgré les intentions des conservateurs de maintenir le statu quo, et, en tout cas, continue à « évoluer » dans la même direction.

Nous voyons, cependant, que la négociation ne bouge que dans une seule direction. Par exemple, supposons que j’offre 50 $ pour un produit et que le vendeur demande 100 $. Nous négocions pour 75 $. Le vendeur connaît alors ma limite. Donc la prochaine fois que nous négocions, nous commençons à 75 $ et il exige 125 $. Si, par indécision, ou si je manque de volonté pour tenir ferme, vous pouvez voir que le prix va continuer à augmenter. Ainsi, les conflits sociaux continuent d’être résolus dans un seul sens, malgré les intentions des conservateurs de maintenir le statu quo, et, en tout cas, continue à « évoluer » dans la même direction.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg