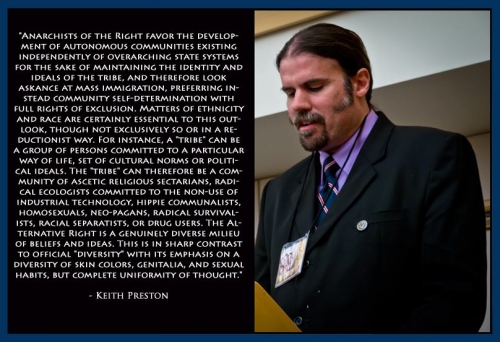

This is the text of a lecture delivered to the H.L. Mencken Club on November 5, 2016.

The topic that I was given for this presentation is “Anarcho-Fascism” which I am sure on the surface sounds like a contradiction in terms. In popular language, the term “fascism” is normally used as a synonym for the totalitarian state. Indeed, in a speech to the Italian Chamber of Deputies on December 9, 1928 Mussolini describe totalitarianism as an ideology that was characterized by the principle of “All within the state, nothing outside the state, nothing against the state.”

However, the most commonly recognized ideological meaning of the term “anarchism” implies the abolition of the state, and the term “anarchy” can either be used in the idealistic sense of total freedom, or in the pejorative sense of chaos and disorder.

Anarchism and fascism are both ideologies that I began to develop an interest in about thirty years ago, when I was a young anarchist militant who spent a great deal of time in the university library reading about the history of classical anarchism. It was during this time that I also became interested in understanding the ideology of fascism, mostly from my readings on the Spanish Civil War, including the works of Dr. Payne, whom I am honored to be on this panel with. And I have also looked into some of these ideas a little more since then. One of the things that I find to be the most fascinating about anarchism as a body of political philosophy is the diversity of anarchist thought. And the more that I have studied right-wing political thought, the more I am amazed by the diversity of opinion to be found there as well. It is consequently very interesting to consider the ways in which anarchism and right-wing political ideologies might intersect.

Anarchism is also normally conceived of as an ideology of the far Left, and certainly the most well-known tendencies within anarchism fit that description. The anarchist movement of the nineteenth and early twentieth century was certainly a movement of the revolutionary Left, and shaped by the thought and actions of radicals such as Pierre Joseph Proudhon, Mikhail Bakunin, Peter Kropotkin, Emma Goldman, the Ukrainian anarchists, the Spanish anarchists, and others. Anarchism of this kind also involved many different ideological sub-tendencies including anarcho-communism, anarcho-syndicalism, collectivist anarchism, and what was known as “propaganda by the deed” which was essentially a euphemism for terrorism, and other forms of anarchism that advocated violent resistance to the state, such as illegalism or insurrectionary anarchism.

There is also a modern anarchist movement that largely functions as a youth subculture within the context of the radical left, and modern anarchism likewise includes many different hyphenated tendencies like “queer anarchism,” “transgender anarchism,” or “anarcha-feminism,” and many of which, as you might guess, maintain a very “politically correct” orientation.

However, there are also ways in which the anarchist tradition overlaps with the extreme right.

The French intellectual historian Francois Richard identified three primary currents within the wider philosophical tradition of anarchism. The first of these is the classical socialist-anarchism that I have previously described that has as its principal focus an orientation towards social justice and uplifting the downtrodden. A second species of anarchism is the radical individualism of Stirner and the English and American libertarians, a perspective that posits individual liberty as the highest good. And still a third tradition is a Nietzsche-influenced aristocratic radicalism, or what the French call “anarchism of the Right” which places its emphasis not only on liberty but on merit, excellence, and the preservation of high culture.

The French intellectual historian Francois Richard identified three primary currents within the wider philosophical tradition of anarchism. The first of these is the classical socialist-anarchism that I have previously described that has as its principal focus an orientation towards social justice and uplifting the downtrodden. A second species of anarchism is the radical individualism of Stirner and the English and American libertarians, a perspective that posits individual liberty as the highest good. And still a third tradition is a Nietzsche-influenced aristocratic radicalism, or what the French call “anarchism of the Right” which places its emphasis not only on liberty but on merit, excellence, and the preservation of high culture.

My actual presentation here today is going to be on the wider traditions of anarchism of the Right, right-wing anti-statism, and Left/Right crossover movements which are influenced by the anarchist tradition.

First, it might be helpful to formulate a working definition of “anarcho-fascism.” An “anarcho-fascist” could be characterized as someone that rejects the legitimacy of a particular state, and possibly even uses illegal or extra-legal means of opposing the established political or legal order, even if they prefer a state, even a fascist state, of their own.

There are looser definitions of “anarcho-fascism” as well, and I will touch on some of these in a moment. However, it should also be pointed out that many anarchists of the right were not part of a movement or any kind of political parties or mass organizations. Instead, their affinity for anarchism was more of an attitude or a philosophical stance although, as I will explain shortly, there were also efforts to translate right-wing anarchist ideas into a program for political action.

Anarchists of the Right during the French Revolution and Pre-Revolutionary Era

Left-wing anarchist thought can to some degree trace its roots to tendencies within revolutionary France of the late eighteenth century, as well as the pre-revolutionary and post-revolutionary periods. This is also true, to some degree, of the right-wing anarchist tradition. Once again, to cite Francois Richard:

“Here, at the end of the 18th century, in the later stages of the ancien régime, formed an anarchisme de droite, whose protagonists claimed for themselves a position “beyond good and evil,” a will to live “like the gods,” and who recognised no moral values beyond personal honour and courage. The world-view of these libertins was intimately connected with an aggressive atheism and a pessimistic philosophy of history. Men like Brantôme, Montluc, Béroalde de Verville and Vauquelin de La Fresnaye held absolutism to be a commodity that regrettably opposed the principles of the old feudal system, and that only served the people’s desire for welfare.” –Francois Richard

These intellectual currents that Richard describes mark the beginning of an “anarchism of right” within the French intellectual tradition. As mentioned previously, these thinkers could certainly be considered forerunners to Nietzsche, and later French thinkers in this tradition included some fairly prominent figures. Among them were the following:

-Arthur de Gobineau, a 19th century writer, and early racialist thinker

-Leon Bloy, a novelist in the late 19th century

-Paul Leautaud, a theater critic in the early 20th century

-Louis Ferdinand Celine, a well-known French writer during the interwar period

-George Bernanos, whose political alignments were those of an anti-fascist conservative, monarchist, Catholic, and nationalist

-Henry de Montherlant, a 20th century dramatist, novelist, and essayist

-Jean Anouilh, a French playwright in the postwar era

Among the common ideas that were shared by these writers were an elitist individualism, aristocratic radicalism, disdain for established ideological or ethical norms, and cultural pessimism; disdain for mass democracy, egalitarianism, and the values of mass society; a dismissive attitude towards conventional society as decadent; adherence to the values of merit and excellence; a commitment to the recognition of the superior individual and an emphasis on high culture; an ambiguity about liberty rooted in a disdain for plebian values; and a characterization of government as a conspiracy against the superior individual.

Outside of France

A number of thinkers also emerged outside of France that shared many ideas in common with the French anarchists of the Right. Ironically, considering where we are today, one of these was H. L. Mencken, who was characterized as an “anarchist of the right” by another French intellectual historian, Anne Ollivier-Mellio, in an academic article some years ago. An overlapping tradition is what has sometimes been referred to as “anarcho-monarchism” which included such figures as the famous author J.R.R. Tolkien in England, the artist Salvador Dali in Spain, the Catholic traditionalist Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn in Austria, and, perhaps most intriguingly, the English occultist Aleister Crowley, who has been widely mischaracterized as a Satanist.

Conservative Revolutionaries

The traditions associated with right-wing anarchism also overlap considerably with the tendency known as the “Conservative Revolution” which developed among right-wing European intellectuals during the interwar period. Among the most significant of these thinkers were Arthur Moeller van den Bruck and Stefan George in Germany, Maurice Barres in France, Gabriele d’Annunzio in Italy, and, considerably later, Yukio Mishima in postwar Japan.

Perhaps the most famous intellectual associated with the Conservative Revolution was Ernst Junger, a veteran of World War One who became famous after publishing his war diaries in Weimar Germany under the title “Storms of Steel.” Much later in life, Junger published a work called “Eumeswil” which postulates the concept of the “Anarch,” a concept that is modeled on Max Stirner’s idea of the “Egoist.” According to Junger’s philosophy, an “Anarch” does not necessarily engage in outward revolt against institutionalized authority. Instead, the revolt occurs on an inward basis, and the individual is able to retain an inner psychic freedom by means of detachment from all external values and an inward retreat into one’s self. In some ways, this is a philosophy that is similar to currents within Buddhism and other Eastern philosophies.

Perhaps the most famous intellectual associated with the Conservative Revolution was Ernst Junger, a veteran of World War One who became famous after publishing his war diaries in Weimar Germany under the title “Storms of Steel.” Much later in life, Junger published a work called “Eumeswil” which postulates the concept of the “Anarch,” a concept that is modeled on Max Stirner’s idea of the “Egoist.” According to Junger’s philosophy, an “Anarch” does not necessarily engage in outward revolt against institutionalized authority. Instead, the revolt occurs on an inward basis, and the individual is able to retain an inner psychic freedom by means of detachment from all external values and an inward retreat into one’s self. In some ways, this is a philosophy that is similar to currents within Buddhism and other Eastern philosophies.

Yet another well-known figure from the Conservative Revolutionary era, and one that is certainly influential among the more radical tendencies on the alternative right today, is Julius Evola. Evola was a proponent of an extreme elitism that characterized the period of the Kali Yuga of Hindu civilization during approximately 800 B.C. as the high point in human development. Indeed, he considered everything that has taken place since then to have been a manifestation of degeneracy. For example, Evola actually criticized fascism and Nazism as having been too egalitarian because of their orientation towards popular mobilization and their appeals to the ethos of mass society. Evola also formulated a concept known as the “absolute individual,” which was very similar to Junger’s notion of the “Anarch,” and which can be described an individual that has achieved a kind of self-overcoming, as Nietzsche would have called it, due to their capacity for rising above the herd instincts of the masses of humankind.

Now, I must emphasize that the points of view that I have outlined thus far were largely attitudes or philosophical stances, not actual programs of political action. However, there have also been actual efforts to combine anarchism or ideas borrowed from anarchism with right-wing ideas, and to translate these into conventional political programs. One of these involves the concept of syndicalism as it was developed by Georges Sorel. Syndicalism is a revolutionary doctrine that advocates the seizure of industry and the government by means of a worker insurrection or what is sometimes called a “general strike.” Syndicalism was normally conceived of as an ideology of the extreme left, like anarchism, but a kind of right-wing syndicalism began to develop in the early twentieth century due to the influence of Sorel and the German-Italian Robert Michels, who formulated the so-called “iron law of oligarchy.” Michaels was a former Marxist who came to believe that all organizations of any size are ultimately organized as oligarchies, where the few lead the many, and believed that anti-capitalist revolutionary doctrines would have to be accommodated to this insight.

Cercle Proudhon

Out of these intellectual tendencies developed an organization called the “Cercle Proudhon,” which combined the ideas of the early anarchist thinker Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, such as mutualist economics and political federalism, with various elitist and right-wing ideas such as French nationalism, monarchism, aristocratic radicalism, and Catholic traditionalism. Cercle Proudhon was also heavily influenced by an earlier movement known as Action France which had been founded by Charles Maurras.

Third Positionism, Distributism and National-Anarchism

Another tendency that is similar to these is what is often called the “Third Position,” a form of revolutionary nationalism that is influenced by the economic theories of Distributism. Distributism was a concept developed by the early 20th century Catholic writers G.K. Chesterton and Hillaire Belloc, which postulated the idea of smaller property holders, consumer cooperatives, workers councils, local democracy, and village-based agrarian societies, and which in many ways overlaps with tendencies on the radical Left such as syndicalism, guild socialism, cooperativism or individualist anarchism. Interestingly, many third positionists are also admirers of Qaddafi’s “Green Book” which outlines a program for the creation of utopian socialist and quasi-anarchist communities that form the basis for an alternative model of society beyond both Capitalism and Communism.

Within more recent times, a tendency has emerged that is known as National-Anarchism, a term that was formed by a personal friend of mine named Troy Southgate, and which essentially synthesizes anarchism with the notion of ethno-cultural identitarianism.

Troy Southgate

Right-wing Anarchism, Libertarianism and Anarcho-Capitalism

Certainly, any discourse on right-wing anarchism needs include a discussion of the sets of ideas that are associated with Libertarianism or Anarcho-Capitalism of the kinds that are associated with an array of free-market individualist thinkers such as Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich August von Hayek, Milton Friedman, and, of course, Ayn Rand and Murray Rothbard.

In many ways, modern libertarianism has a prototype in the extreme individualism of Max Stirner, and perhaps in thought of Henry David Thoreau as well. The more recent concept of anarcho-capitalism was developed in its most far reaching form by Murray Rothbard and his disciple, Hans Hermann Hoppe. Indeed, Hoppe has developed a critique of modern systems of mass democracy of a kind that closely resembles that of earlier thinkers in the tradition of the French “anarchists of the Right,” Mencken, and Kuehnelt-Leddihn.

It is also interesting to note that some of the late twentieth century proponents of individualist anarchism such as James J. Martin and Samuel E. Konkin III, the founder of a tendency within libertarianism known as agorism, were also proponents of Holocaust revisionism. Indeed, when I was doing research on the modern libertarian movement, I discovered that Holocaust revisionism was actually popular among libertarians in the 1970s, not on anti-Semitic or pro-Nazi grounds, but out of a desire to defend the original isolationist case against World War Two. Konkin himself was actually associated with the Institute for Historical Review at one point.

It is also interesting to note that some of the late twentieth century proponents of individualist anarchism such as James J. Martin and Samuel E. Konkin III, the founder of a tendency within libertarianism known as agorism, were also proponents of Holocaust revisionism. Indeed, when I was doing research on the modern libertarian movement, I discovered that Holocaust revisionism was actually popular among libertarians in the 1970s, not on anti-Semitic or pro-Nazi grounds, but out of a desire to defend the original isolationist case against World War Two. Konkin himself was actually associated with the Institute for Historical Review at one point.

Samuel E. Konkin III

There are also various types of conservative Christian anarchism that postulated the concept of parish-based village communities with cooperative or agrarian economies. Such tendencies exist within the Catholic, Protestant and Orthodox traditions alike. For example, Father Matthew Raphael Johnson, a former editor of the Barnes Review, is a proponent of such an outlook.

Very similar concepts to conservative Christian anarchism can also be found within neo-pagan tendencies which sometimes advocate a folkish or traditionalist anarchism of their own.

Left/Right Overlaps and Crossover Movements

A fair number of tendencies can be identified that involved left/right overlaps or crossover movements of some particular kind. One of these was formulated by Gustav Landauer, a German anarcho-communist that was killed by the Freikorps during the revolution of 1919. Landauer was also a German nationalist, and proposed a folkish anarchism that recognized the concept of national, regional, local and ethnic identities that existed organically and independently of the state. For example, Landauer once characterized himself as a German, a Bavarian, and a Jew who was also an anarchist.

In the early 1980s, a tendency emerged in England known as the Black Ram, which advocated for an anarcho-nationalism that sought to address the concept of national identity as this related to left-wing anarchism. Black Ram was a conventionally left-wing tendency in the sense of being anti-statist, anti-capitalist, anti-racist, and anti-sexist, but which understood nationalities to be pre-existing cultural and ethnic expressions that were external to the state as an authoritarian institution.

Dorothy Day was an American radical, a religious pacifist, and advocate of social justice, who combined anarchism and Catholic traditionalism. She was the founder of the Catholic Worker movement, and considered herself to be a supporter of both the Industrial Workers of the World and the Vatican.

Dorothy Day was an American radical, a religious pacifist, and advocate of social justice, who combined anarchism and Catholic traditionalism. She was the founder of the Catholic Worker movement, and considered herself to be a supporter of both the Industrial Workers of the World and the Vatican.

One of the godfathers of classical anarchism was, of course, Mikhail Bakunin, who was himself a pan-Slavic nationalist, and continues to be a peripheral influence on the European New Right. In fact, Alain De Benoist’s concept of “federal populism” owes much to Bakunin’s thought and is remarkably similar to Bakunin’s advocacy of a federation of participatory democracies.

Dorothy Day

There are a number of left-wing anarchists that have profoundly influenced the ecology movement that have also provided inspiration for various thinkers of the Right. Kirkpatrick Sale, for example, is a neo-Luddite and the originator of a concept known as bioregionalism. Leopold Kohr is best known for his advocacy of the “breakdown of nations” into decentralized, autonomous micro-nations. E.F. Schumacher is, of course, known for his classic work in decentralist economics, “Small is Beautiful.” Each of these thinkers is also referenced in Wilmot Robertson’s white nationalist manifesto, “The Ethnostate.”

Anarchism and Right-Wing Populism

Because American political culture contains strands of both anti-state radicalism and right-wing populism, it is also important to consider the ways in which these overlap or run parallel to each other. For example, there are tendencies among far right political undercurrents that favor a radically decentralized or even anarchic social order, but which also adhere to anti-Semitic conspiracy theories or racial superiority theories. There is actually a tradition like that on the US far right associated with groups like the Posse Comitatus.

There is also a radical right Christian movement that favors county level government organized as an uber-reactionary theocracy (like Saudi Arabia, only Christian). Other tendencies can be observed that favor no government beyond the county level, such as the sovereign citizens, who regard speed limits and drivers’ licensing requirements to be egregious violations of liberty, the proponents of extra-legal common laws courts, and various other trends within the radical patriot movement.

The relationship between the Right and the state in many ways mirrors that of the Left in the sense that both Right and Left have something of a triangular interaction with systems of institutional and legal authority. Both Left and Right can be divided into reformist, libertarian, or totalitarian camps. In the case of the Left, a leftist may be a reform liberal or social democrat, they may be an anarchist or a left-libertarian, or they may be a totalitarian in the tradition of Lenin, Stalin, Mao, and others. Similarly, a rightist may advocate for reforms of a conservative or rightward leaning nature, they may be an anarchist of the right or a radical anti-statist, or a person of the Right may be a proponent of some kind of right-wing authoritarianism, or a totalitarian in the fascist tradition.

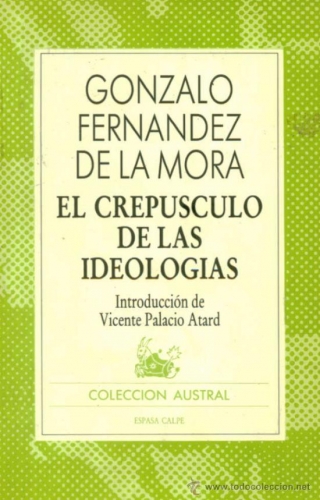

Yo también lo creo, y en esto coincido con Fernández de la Mora. Nos hace falta una filosofía, y no una filosofía cualquiera. Nos hace falta una filosofía positiva. Entiéndaseme bien: positiva no significa positivista. De esta otra ya andamos sobrados. No faltan columnistas, periodistas, científicos sociales y naturales, expertos en "H" o en "B", que lanzan al aire y a las masas la carnaza positivista de que la "filosofía no sirve para nada" y venden la baratija de que, a lo sumo, un mero análisis lógico y lingüístico de los enunciados es cuanto queda por hacer al filósofo profesional. Eso, o la divulgación generalista, el trenzado ideológico-partidista o la labor anticuaria de rescatar y exponer "ideas del pasado". El neopositivismo anglosajón y colonizador fue parte del recado atlantista que nos llegó tras la "apertura" de nuestro país a la ayuda y a la influencia angloamericana en pleno franquismo, y se tradujo en la creación masiva de cátedras y plazas docentes de una filosofía –- la "analítica" –- que no era nuestra y que nada nos decía. Pudo ser una alternativa "modernizadora" ante el acartonamiento escolástico de la universidad franquista, es cierto, un acicate, siempre saludable, para estudiar lógica formal o interesarse por la epistemología de las ciencias "duras", pero poco más.

Yo también lo creo, y en esto coincido con Fernández de la Mora. Nos hace falta una filosofía, y no una filosofía cualquiera. Nos hace falta una filosofía positiva. Entiéndaseme bien: positiva no significa positivista. De esta otra ya andamos sobrados. No faltan columnistas, periodistas, científicos sociales y naturales, expertos en "H" o en "B", que lanzan al aire y a las masas la carnaza positivista de que la "filosofía no sirve para nada" y venden la baratija de que, a lo sumo, un mero análisis lógico y lingüístico de los enunciados es cuanto queda por hacer al filósofo profesional. Eso, o la divulgación generalista, el trenzado ideológico-partidista o la labor anticuaria de rescatar y exponer "ideas del pasado". El neopositivismo anglosajón y colonizador fue parte del recado atlantista que nos llegó tras la "apertura" de nuestro país a la ayuda y a la influencia angloamericana en pleno franquismo, y se tradujo en la creación masiva de cátedras y plazas docentes de una filosofía –- la "analítica" –- que no era nuestra y que nada nos decía. Pudo ser una alternativa "modernizadora" ante el acartonamiento escolástico de la universidad franquista, es cierto, un acicate, siempre saludable, para estudiar lógica formal o interesarse por la epistemología de las ciencias "duras", pero poco más. Las quejas de G. Fernández de la Mora, así como sus proyectos modernizadores, han quedado en el olvido. El cambio de Régimen, desde el franquismo (sistema en el cual éste pensador fue destacado miembro, e incluso ministro) hacia la Restauración borbónico-constitucional (R78) supuso el olvido e incluso la postergación de su obra. El filósofo conservador, pero en absoluto fascista, había concebido una España moderna en el plano científico y tecnológico, una España en la cual primaran el mérito, la capacidad, la preparación, y en donde se proscribiera para siempre la demagogia, el juego doctrinario, la retórica verbal y el patetismo. Es una voz la de Fernández de la Mora que no ha sido escuchada. Una España que la escuchara, será una nación radicalmente otra, renovada y sin prejuicios.

Las quejas de G. Fernández de la Mora, así como sus proyectos modernizadores, han quedado en el olvido. El cambio de Régimen, desde el franquismo (sistema en el cual éste pensador fue destacado miembro, e incluso ministro) hacia la Restauración borbónico-constitucional (R78) supuso el olvido e incluso la postergación de su obra. El filósofo conservador, pero en absoluto fascista, había concebido una España moderna en el plano científico y tecnológico, una España en la cual primaran el mérito, la capacidad, la preparación, y en donde se proscribiera para siempre la demagogia, el juego doctrinario, la retórica verbal y el patetismo. Es una voz la de Fernández de la Mora que no ha sido escuchada. Una España que la escuchara, será una nación radicalmente otra, renovada y sin prejuicios. Fernández de la Mora proclamaba sustituir las ideologías, ya moribundas, por ideas. Trocar a los demagogos y a los declamadores por expertos. En vez de entusiasmo, peligroso explosivo que siempre deviene en tiranía, consenso. El consenso tácito y la deliberación fría deben ocupar su puesto rector en lugar de la asamblea tumultuaria. El análisis sosegado de proyectos racionales en vez de agitación y propaganda. Qué duda cabe que la filosofía positiva no corrió la mejor de las fortunas una vez desembocada la partidocracia del R78. El régimen constitucional postfranquista ensalzó la retórica partidista y encumbró a un sinfín de ideólogos, retóricos vanos, arribistas, vividores "liberados" de los sindicatos y de los aparatos electoralistas. Los expertos, las personas formadas en las distintas ramas de la vida orgánica del Estado (administradores, expertos juristas, tecnólogos, economistas planificadores…) hubieron de ceder sus sillas o pasar a un discreto y segundo plano ante el soberano imperio de los grandilocuentes vendedores de humo. Incluso dentro de la democracia postfranquista se advierten claramente dos generaciones: una, primera, aún bien acreditada en cuanto a titulación académica y experiencia práctica en la empresa pública o en la privada, y otra, segunda, en la que ahora más y más nos hundimos, en la cual el lumpen de la sociedad, los sectores sociales más refractarios al esfuerzo intelectual, profesional y, en general, humano, se dedican, con el carnet en la boca, a ascender por los aparatos electoralistas para conseguir aplausos fáciles y cargos sine cura.

Fernández de la Mora proclamaba sustituir las ideologías, ya moribundas, por ideas. Trocar a los demagogos y a los declamadores por expertos. En vez de entusiasmo, peligroso explosivo que siempre deviene en tiranía, consenso. El consenso tácito y la deliberación fría deben ocupar su puesto rector en lugar de la asamblea tumultuaria. El análisis sosegado de proyectos racionales en vez de agitación y propaganda. Qué duda cabe que la filosofía positiva no corrió la mejor de las fortunas una vez desembocada la partidocracia del R78. El régimen constitucional postfranquista ensalzó la retórica partidista y encumbró a un sinfín de ideólogos, retóricos vanos, arribistas, vividores "liberados" de los sindicatos y de los aparatos electoralistas. Los expertos, las personas formadas en las distintas ramas de la vida orgánica del Estado (administradores, expertos juristas, tecnólogos, economistas planificadores…) hubieron de ceder sus sillas o pasar a un discreto y segundo plano ante el soberano imperio de los grandilocuentes vendedores de humo. Incluso dentro de la democracia postfranquista se advierten claramente dos generaciones: una, primera, aún bien acreditada en cuanto a titulación académica y experiencia práctica en la empresa pública o en la privada, y otra, segunda, en la que ahora más y más nos hundimos, en la cual el lumpen de la sociedad, los sectores sociales más refractarios al esfuerzo intelectual, profesional y, en general, humano, se dedican, con el carnet en la boca, a ascender por los aparatos electoralistas para conseguir aplausos fáciles y cargos sine cura. Don Gonzalo despedía con alegría al tipo de político retórico y declamador, pero experto en nada, que había dominado la escena pública europea durante todo el siglo XIX y que aún prolongaba su inútil existencia en el XX. A la par, el filósofo bendecía en "El Crepúsculo de las Ideologías" al tecnócrata, al experto, al "conocedor" que no busca encandilar a las masas, manipularlas y tocar las fibras de su entusiasmo, sino ser eficaz servidor público que plantea objetivos realistas en orden a una mejora del bienestar general, haciendo del Estado una maquinaria ágil, inteligente, bien engrasada. Una maquinaria que ha de renunciar, bajo riesgo de recaer en el ideologismo y en el utopismo más peligrosos, a reformar al hombre.

Don Gonzalo despedía con alegría al tipo de político retórico y declamador, pero experto en nada, que había dominado la escena pública europea durante todo el siglo XIX y que aún prolongaba su inútil existencia en el XX. A la par, el filósofo bendecía en "El Crepúsculo de las Ideologías" al tecnócrata, al experto, al "conocedor" que no busca encandilar a las masas, manipularlas y tocar las fibras de su entusiasmo, sino ser eficaz servidor público que plantea objetivos realistas en orden a una mejora del bienestar general, haciendo del Estado una maquinaria ágil, inteligente, bien engrasada. Una maquinaria que ha de renunciar, bajo riesgo de recaer en el ideologismo y en el utopismo más peligrosos, a reformar al hombre. Un ejemplo de cómo esta filosofía de ideas y no de utopías ideológicas perdió la batalla, y el vicio del ideologismo alcanzó el triunfo, fue el rosario de las reformas educativas de la democracia. Cada nueva ley de educación, comenzando con la barbarie de la LOGSE, hasta llegar a la actual LOMCE, demostró ser la consagración del ideologismo. En lugar de dotar al Estado de ideas, ideas tonificantes, hemos tenido ideología y más ideología. España necesitaba ideas en el sentido filosófico, esto es, conceptos generales (trans-categoriales) que hundieran sus raíces en los más variados conceptos y categorías científicas y técnicas, ideas que, debidamente entretejidas, formaran un proyecto comunitario para "poner a punto" nuestra sociedad y vuelvan a "ajustar" debidamente a España en el orden internacional, colocándola en el puesto que le compete y que se merece ateniéndose a su Historia y a su Presente. Pues bien, en lugar de eso, hemos sido víctimas de los pedagogos, esto es, de los ideólogos, que de manera harto interesada nos equipararon a todos por lo bajo, sustituyendo el imperativo del esfuerzo por la "integración" y halagando al vago y al parásito, con la esperanza de que sean muchedumbre los que sigan depositando en los mismos ataúdes ideológicos el voto mayoritario de los borregos.

Un ejemplo de cómo esta filosofía de ideas y no de utopías ideológicas perdió la batalla, y el vicio del ideologismo alcanzó el triunfo, fue el rosario de las reformas educativas de la democracia. Cada nueva ley de educación, comenzando con la barbarie de la LOGSE, hasta llegar a la actual LOMCE, demostró ser la consagración del ideologismo. En lugar de dotar al Estado de ideas, ideas tonificantes, hemos tenido ideología y más ideología. España necesitaba ideas en el sentido filosófico, esto es, conceptos generales (trans-categoriales) que hundieran sus raíces en los más variados conceptos y categorías científicas y técnicas, ideas que, debidamente entretejidas, formaran un proyecto comunitario para "poner a punto" nuestra sociedad y vuelvan a "ajustar" debidamente a España en el orden internacional, colocándola en el puesto que le compete y que se merece ateniéndose a su Historia y a su Presente. Pues bien, en lugar de eso, hemos sido víctimas de los pedagogos, esto es, de los ideólogos, que de manera harto interesada nos equipararon a todos por lo bajo, sustituyendo el imperativo del esfuerzo por la "integración" y halagando al vago y al parásito, con la esperanza de que sean muchedumbre los que sigan depositando en los mismos ataúdes ideológicos el voto mayoritario de los borregos.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

The French intellectual historian Francois Richard identified three primary currents within the wider philosophical tradition of anarchism. The first of these is the classical socialist-anarchism that I have previously described that has as its principal focus an orientation towards social justice and uplifting the downtrodden. A second species of anarchism is the radical individualism of Stirner and the English and American libertarians, a perspective that posits individual liberty as the highest good. And still a third tradition is a Nietzsche-influenced aristocratic radicalism, or what the French call “anarchism of the Right” which places its emphasis not only on liberty but on merit, excellence, and the preservation of high culture.

The French intellectual historian Francois Richard identified three primary currents within the wider philosophical tradition of anarchism. The first of these is the classical socialist-anarchism that I have previously described that has as its principal focus an orientation towards social justice and uplifting the downtrodden. A second species of anarchism is the radical individualism of Stirner and the English and American libertarians, a perspective that posits individual liberty as the highest good. And still a third tradition is a Nietzsche-influenced aristocratic radicalism, or what the French call “anarchism of the Right” which places its emphasis not only on liberty but on merit, excellence, and the preservation of high culture. Perhaps the most famous intellectual associated with the Conservative Revolution was Ernst Junger, a veteran of World War One who became famous after publishing his war diaries in Weimar Germany under the title “Storms of Steel.” Much later in life, Junger published a work called “Eumeswil” which postulates the concept of the “Anarch,” a concept that is modeled on Max Stirner’s idea of the “Egoist.” According to Junger’s philosophy, an “Anarch” does not necessarily engage in outward revolt against institutionalized authority. Instead, the revolt occurs on an inward basis, and the individual is able to retain an inner psychic freedom by means of detachment from all external values and an inward retreat into one’s self. In some ways, this is a philosophy that is similar to currents within Buddhism and other Eastern philosophies.

Perhaps the most famous intellectual associated with the Conservative Revolution was Ernst Junger, a veteran of World War One who became famous after publishing his war diaries in Weimar Germany under the title “Storms of Steel.” Much later in life, Junger published a work called “Eumeswil” which postulates the concept of the “Anarch,” a concept that is modeled on Max Stirner’s idea of the “Egoist.” According to Junger’s philosophy, an “Anarch” does not necessarily engage in outward revolt against institutionalized authority. Instead, the revolt occurs on an inward basis, and the individual is able to retain an inner psychic freedom by means of detachment from all external values and an inward retreat into one’s self. In some ways, this is a philosophy that is similar to currents within Buddhism and other Eastern philosophies.

It is also interesting to note that some of the late twentieth century proponents of individualist anarchism such as James J. Martin and Samuel E. Konkin III, the founder of a tendency within libertarianism known as agorism, were also proponents of Holocaust revisionism. Indeed, when I was doing research on the modern libertarian movement, I discovered that Holocaust revisionism was actually popular among libertarians in the 1970s, not on anti-Semitic or pro-Nazi grounds, but out of a desire to defend the original isolationist case against World War Two. Konkin himself was actually associated with the Institute for Historical Review at one point.

It is also interesting to note that some of the late twentieth century proponents of individualist anarchism such as James J. Martin and Samuel E. Konkin III, the founder of a tendency within libertarianism known as agorism, were also proponents of Holocaust revisionism. Indeed, when I was doing research on the modern libertarian movement, I discovered that Holocaust revisionism was actually popular among libertarians in the 1970s, not on anti-Semitic or pro-Nazi grounds, but out of a desire to defend the original isolationist case against World War Two. Konkin himself was actually associated with the Institute for Historical Review at one point. Dorothy Day was an American radical, a religious pacifist, and advocate of social justice, who combined anarchism and Catholic traditionalism. She was the founder of the Catholic Worker movement, and considered herself to be a supporter of both the Industrial Workers of the World and the Vatican.

Dorothy Day was an American radical, a religious pacifist, and advocate of social justice, who combined anarchism and Catholic traditionalism. She was the founder of the Catholic Worker movement, and considered herself to be a supporter of both the Industrial Workers of the World and the Vatican. We are soldiers because we refuse the reformist tinkering of the dominant system, which — through its electoral and party committees, its partisan venalities, and its parliamentary charade — endeavors to ensure the self-regulation and recycling of the corrupt elites controlling the existing plutocratic system.

We are soldiers because we refuse the reformist tinkering of the dominant system, which — through its electoral and party committees, its partisan venalities, and its parliamentary charade — endeavors to ensure the self-regulation and recycling of the corrupt elites controlling the existing plutocratic system.