Review:

George Hawley

Right-Wing Critics of American Conservatism [2]

Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 2016

Most academic studies of White Nationalism and the New Right do not rise above politically correct sneers and smears. They read like ADL or SPLC reports fed through a postmodern buzzword generator. Thus the growing number of serious and balanced academic studies and White Nationalism and the New Right are signs of our rising cultural profile. It is increasingly difficult to dismiss us.

For instance, The Struggle for the World: Liberation Movements for the 21st Century [3]

For instance, The Struggle for the World: Liberation Movements for the 21st Century [3], the 2010 Stanford University Press book on anti-globalization movements by Charles Lindholm and José Pedro Zúquete contains a quite balanced and well-informed chapter on the European New Right. (See Michael O’Meara’s review here [4].) Moreover, Zúquete’s 2007 Syracuse University Press volume Missionary Politics in Contemporary Europe [5]

contains extensive chapters on the French National Front and Italy’s Northern League.

Political scientist George Hawley’s new book Right-Wing Critics of American Conservatism is another important contribution to this literature, devoting a chapter to the European New Right and another chapter to White Nationalism. I’m something of an expert in these fields, and in my judgment, Hawley’s research is deft, thorough, and accurate. His writing is admirably clear, and his analysis is quite penetrating.

Naturally, the first thing I did was flip to the index to look for my own name, and, sure enough, on page 265 I found the following:

In recent years, elements of the radical right in the United States have exhibited greater interest in right-wing ideas from continental Europe. In 2010, the North American New Right was founded by Greg Johnson, the former editor of the Occidental Quarterly. While clearly focused on promoting white nationalism in the United States, the North American New Right is heavily influenced by both Traditionalism and the European New Right, and its website (http://www.counter-currents.com/) regularly includes translations from many European New Right intellectuals. The site also embraces the New Right’s idea of metapolitics, noting that the time will not be right for white nationalists to engage in more conventional political activities until a critical number of intellectuals have been persuaded that their ideas are morally and intellectually correct.

The work of my friends at Arktos in bringing out translations of European New Right thinkers is also mentioned on page 241.

Hawley’s definitions of Right and Left come from Paul Gottfried, although they accord exactly with my own views and those of Jonathan Bowden: the Left treats equality as the highest political value. The Right does not regard equality as the highest political value, although there is a range of opinions about what belongs in that place (pp. 11-12). Libertarians, for instance, regard individual liberty as more important than equality. White Nationalists think that both liberty and equality have some value, but racial health and progress trump them both.

In chapter 1, Hawley argues that modern American conservatism was defined by William F. Buckley and National Review in the 1950s. The conservative movement was a coalition of free market capitalists, Christians, and foreign policy hawks. Hawley points out that based on ideology alone, there is no necessary reason why any of these groups would be Right wing or allied with each other. Indeed, the pre-World War II “Old Right” of people like Albert Jay Nock and H. L. Mencken tended to be anti-interventionist, irreligious, and economically populist and protectionist rather than free market. National Review was also philo-Semitic from the start and increasingly anti-racist, whereas the pre-War American Right had strong racialist and anti-Semitic elements. What unified the National Review coalition was not a common ideology but a common enemy: Communism.

In chapter 1, Hawley argues that modern American conservatism was defined by William F. Buckley and National Review in the 1950s. The conservative movement was a coalition of free market capitalists, Christians, and foreign policy hawks. Hawley points out that based on ideology alone, there is no necessary reason why any of these groups would be Right wing or allied with each other. Indeed, the pre-World War II “Old Right” of people like Albert Jay Nock and H. L. Mencken tended to be anti-interventionist, irreligious, and economically populist and protectionist rather than free market. National Review was also philo-Semitic from the start and increasingly anti-racist, whereas the pre-War American Right had strong racialist and anti-Semitic elements. What unified the National Review coalition was not a common ideology but a common enemy: Communism.

In chapter 2, Hawley also documents the role of social mechanisms like purges in defining post-war conservatism. Buckley set the pattern early on by purging Ayn Rand and the Objectivists (for being irreligious) and the John Birch Society (for being conspiratorial and cranky), going on in later years to purge anti-Semites, immigration restrictionists, anti-interventionists, race realists, etc. The same pattern was followed with the firing of race realists Sam Francis from The Washington Times and Jason Richwine from the Heritage Foundation. Indeed, many of the leading figures in the movements Hawley chronicles were purged from mainstream conservatism.

Mainstream conservatism embraces globalization through free trade, immigration, and military interventionism. Thus Hawley devotes chapter 3, “Small is Beautiful,” to conservative critics of globalization, with discussions of the Southern Agrarians, including Richard Weaver and Wendell Berry, communitarian sociologists Robert Nisbet and Christopher Lasch, and economic localists Wilhelm Röpke and E. F. Schumacher. I spent a good chunk of my 20s reading this kind of literature, as well as the libertarian and paleoconservative writers Hawley discusses in later chapters. Thus Hawley’s book can serve as an introduction and a syllabus to a lot of the Anglophone literature that I traversed before coming to my present views.

The Southern Agrarians are particularly interesting, because of they were the most radical school of American conservatism, offering a genuinely anti-liberal and anti-modernist critique of Americanism, with many parallels to what later emerged from the European New Right. The Agrarians also understood the importance of metapolitics. Unfortunately, they were primarily a literary movement and had no effect on political policy. Although I am not a Southerner, I spent a lot of time reading first generation Agrarians like Allen Tate, Donald Davidson, and John Crowe Ransom, plus Weaver, Berry, and Marion Montgomery, and their influence made me quite receptive to the European New Right.

Christians form an important although subaltern bloc in the conservative coalition, thus Hawley devotes chapter 4 to a brief discussion of “Godless Conservatism,” i.e., attempts to make non-religious cases for conservatism. Secular cases for conservatism will only become more important as Christianity continues to decline in America. (Hawley deals with neopagan and Traditionalist alternatives to Christianity in his chapter on the European New Right.)

Chapter 5, “Ready for Prime Time?” is devoted to mainstream libertarianism, including Milton Friedman, the Koch Brothers, the Cato Institute, Reason magazine, the Ron Paul movement, and libertarian youth organizations. Chapter 6, “Enemies of the State,” deals with more radical strands of libertarianism, including 19th-century American anarchists like Josiah Warren and Lysander Spooner, the Austrian School of economics, Murray Rothbard, Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Lew Rockwell, the Mises Institute, and the Libertarian Party. Again, Hawley has read widely with an unfailing eye for essentials.

Chapter 5, “Ready for Prime Time?” is devoted to mainstream libertarianism, including Milton Friedman, the Koch Brothers, the Cato Institute, Reason magazine, the Ron Paul movement, and libertarian youth organizations. Chapter 6, “Enemies of the State,” deals with more radical strands of libertarianism, including 19th-century American anarchists like Josiah Warren and Lysander Spooner, the Austrian School of economics, Murray Rothbard, Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Lew Rockwell, the Mises Institute, and the Libertarian Party. Again, Hawley has read widely with an unfailing eye for essentials.

I went through a libertarian phase in my teens and 20s, and I understand from the inside how someone can move from libertarian individualism to racial nationalism. In 2009, when I was editor of The Occidental Quarterly, I sensed that the Ron Paul and Tea Party movements would eventually send many disillusioned libertarians in the direction of White Nationalism. Thus, to encourage our best minds to think through this connection and develop arguments that might aid the conversion process, TOQ sponsored an essay contest on Libertarianism and Racial Nationalism [6]. Since 2012, this trend has markedly accelerated. Thus I highly recommend Hawley’s chapters to White Nationalists who lack a libertarian background and wish to understand this increasingly important “post-libertarian” strand of the Alternative Right.

Chapter 7, “Nostalgia as a Political Platform,” deals with the paleoconservative movement, covering its debts to the pre-War Old Right, M. E. Bradford, Patrick Buchanan, Thomas Fleming and Chronicles magazine, Sam Francis, Joe Sobran, the paleo-libertarian moment, and Paul Gottfried.

Paleoconservatism is defined in opposition to neoconservatism, the largely Jewish intellectual movement that largely took over mainstream conservatism by the 1980s, aided by William F. Buckley who dutifully purged their opponents. Since the neoconservatives are largely Jewish, and many of the founders were ex-Marxists or Cold War liberals, their ascendancy has meant the subordination of Christian conservatives and free marketeers to the hawkish interventionist wing of the movement. Now that the Cold War is over, the primary concern of neoconservative hawks is tricking Americans into fighting wars for Israel.

Paleoconservatism is defined in opposition to neoconservatism, the largely Jewish intellectual movement that largely took over mainstream conservatism by the 1980s, aided by William F. Buckley who dutifully purged their opponents. Since the neoconservatives are largely Jewish, and many of the founders were ex-Marxists or Cold War liberals, their ascendancy has meant the subordination of Christian conservatives and free marketeers to the hawkish interventionist wing of the movement. Now that the Cold War is over, the primary concern of neoconservative hawks is tricking Americans into fighting wars for Israel.

Paleoconservatives, by contrast, are actually conservatives. They are defenders of Western civilization and its moral traditions. Many of them are Christians, but not all of them. To a man, they reject multiculturalism and open borders. They are populist-nationalist opponents of economic globalization and political empire-building. Most of them are realists about racial differences.

The paleocons, therefore, are the movement that is intellectually closest to White Nationalism. Indeed, Sam Francis is now seen as a founding figure in contemporary White Nationalism, and both Gottfried and Sobran have spoken at White Nationalist events. Paleoconservatives were also the first Americans to pay sympathetic attention to the European New Right. Thus it makes sense that Hawley places his chapter on paleoconservatism before his chapters on the European New Right and White Nationalism.

Hawley is right that paleoconservatism is basically a spent force. Its leading figures are dead or elderly. Aside from Patrick Buchanan, the movement never had access to the mainstream media and publishers. Unlike mainstream conservative and neoconservative institutions, the paleocons never had large donors and foundations on their side. Beyond that, there is no next generation of paleocons. Instead, their torch is being carried forward by White Nationalists or the more nebulously defined “Alternative Right.”

Chapter 8, “Against Capitalism, Christianity, and America,” surveys the European New Right, beginning with the Conservative Revolutionaries Oswald Spengler, Ernst Jünger, and Arthur Moeller van den Bruck; the Traditionalism of René Guénon and Julius Evola; and finally the New Right proper of Alain de Benoist, Guillaume Faye, and Alexander Dugin.

Chapter 9, “Voices of the Radical Right,” covers White Nationalism in America, with discussions of progressive era racialists like Madison Grant and Lothrop Stoddard; contemporary race realism; the rise and decline of such organizations as the KKK, American Nazi Party, Aryans Nations, and the National Alliance; the world of online White Nationalism; and Kevin MacDonald’s work on the Jewish question — which brings us up to where we started, namely the task of forging a North American New Right.

Chapter 9, “Voices of the Radical Right,” covers White Nationalism in America, with discussions of progressive era racialists like Madison Grant and Lothrop Stoddard; contemporary race realism; the rise and decline of such organizations as the KKK, American Nazi Party, Aryans Nations, and the National Alliance; the world of online White Nationalism; and Kevin MacDonald’s work on the Jewish question — which brings us up to where we started, namely the task of forging a North American New Right.

Hawley’s concluding chapter 10 deals with “The Crisis of Conservatism.” Neoconservatism has, of course, been largely discredited by the debacle in Iraq. Since the Republicans are the de facto party of whites, especially white Christians with families, the deeper and more systemic challenges to the conservative coalition include the decline of Christianity in America, the decline of marriage and the family, and especially the growing non-white population, which overwhelmingly supports progressive policies. The conservative electorate is shrinking, and if it continues to decline, it will eventually be impossible for Republicans to be elected, which means the end of conservative political policies.

There is, however, a deeper cause of the crisis of conservatism. The decline of the family and the growth of the non-white electorate are the predictable results of government policies — policies that conservatives did not resist and that they will not try to roll back, ultimately because conservatives are more committed to classical liberal principles than the preservation of their own political power, which can only be secured by “collectivist,” indeed “racist” measures to preserve the white majority. Conservatives will conserve nothing [7] until they get over their ideological commitment to liberal individualism.

Hawley predicts that as the conservative movement breaks down, some Americans will turn toward more radical Right-wing ideologies, leading to greater political polarization and instability. Of the ideologies Hawley surveys, he thinks the localists, secularists, libertarian anarchists, paleocons, and European New Rightists have the least political potential. Hawley thinks that the moderate libertarians have the most political potential, largely because they are closest to the existing Republican Party. Unfortunately, libertarian radical individualism would only accelerate the decline of the family, Christianity, and the white electorate.

Of all the movements Hawley surveys, only White Nationalism would address the causes of the decline of the white family and the white electorate. But Hawley thinks that White Nationalism faces immense challenges, although the continued decline of the conservative movement might also present us with great opportunities:

Explicit white nationalism is surely the most aggressively marginalized ideology discussed here. As we have seen, advocating racism is perhaps the fastest way for a politician, pundit, or public intellectual to find himself or herself a social pariah. That being the case, there is little chance that transparent white racism will again become a major political force in the United States in the immediate future. However, the fact that antiracists on the right and left are extraordinarily vigilant in their effort to drive racists from public discourse can be viewed as evidence that they believe such views could once again have a large constituency, should racists ever again be allowed to reenter the mainstream public debate. Whether their fears in this regard are justified is impossible to determine at this time. What we should remember, however, is that the marginalization of the racist right in America was largely possible thanks to cooperation from the mainstream conservative movement, which has frequently jettisoned people from its ranks for openly expressing racist views. If the mainstream conservative movement loses its status as the gatekeeper on the right, white nationalism may be among the greatest beneficiaries, though even in this case it will face serious challenges. (p. 291)

Right-Wing Critics of American Conservatism is an important academic study, but it has a significant oversight. The meteoric rise of Donald Trump illustrates the power of another Right-wing alternative to American conservatism, namely populism. Populism is a genuinely Right-wing movement, because although it is critical of economic and political inequality as threats to the integrity of the body politic, populism is nationalistic. It does not regard citizens and foreigners as of equal worth.

I also noticed a couple of smaller mistakes. F. A. Hayek is twice referred to as a Jew, which is false, and on page 40 Hawley refers to Young Americans for Liberty when he means Young Americans for Freedom. Hawley uses the repulsive euphemism “undocumented immigrant” and repeatedly uses the word “vicious” to describe ideas he dislikes, but as a whole his book is relatively free of the tendentious jargon of liberal academics.

I highly recommend Right-Wing Critics of American Conservatism [2]. Hawley is clearly not a friend of conservatism or White Nationalism. He’s something far more useful: a frank and fair-minded critic. Conservatives, of course, lack the capacity for self-criticism and self-preservation. So they will ignore him, to their detriment. But White Nationalists will read him and profit from it.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Seul De Gaulle sauvera sa tête avec les honneurs dans ce livre de 369 pages, mais Pompidou et Giscard d'Estaing n'y sont pas trop maltraités non plus.

Seul De Gaulle sauvera sa tête avec les honneurs dans ce livre de 369 pages, mais Pompidou et Giscard d'Estaing n'y sont pas trop maltraités non plus.  Marcel Gauchet est-il dans le vrai lorsqu'il prétend que nous n'avons pas besoin des intellectuels dans une "fonction critique" et de dénonciation qui ne demande "aucune compétence particulière". Un rôle qui serait maintenant réservé à "l'expert" au service des médias. Même si "l'apparence de survie des intellectuels" ne serait due qu'à l'utilisation de ces médias. "Un monde journalistique" qui est devenu un véritable anti-pouvoir plutôt qu'un contre-pouvoir" qui "exerce une sorte de censure à priori de l'action politique".

Marcel Gauchet est-il dans le vrai lorsqu'il prétend que nous n'avons pas besoin des intellectuels dans une "fonction critique" et de dénonciation qui ne demande "aucune compétence particulière". Un rôle qui serait maintenant réservé à "l'expert" au service des médias. Même si "l'apparence de survie des intellectuels" ne serait due qu'à l'utilisation de ces médias. "Un monde journalistique" qui est devenu un véritable anti-pouvoir plutôt qu'un contre-pouvoir" qui "exerce une sorte de censure à priori de l'action politique".

Mais ce qui fait de Jünger un « nationaliste » dans les années 1920, c’est la lecture de Maurice Barrès. Pourquoi ? Avant la Grande Guerre, on était conservateur (mais non révolutionnaire !). Désormais, avec le mythe du sang, chanté par Barrès, on devient un révolutionnaire nationaliste. Le vocable, plutôt nouveau aux débuts de la république de Weimar, indique une radicalisation politique et esthétique qui rompt avec les droites conventionnelles. L’Allemagne, entre 1918 et 1923, est dans la même situation désastreuse que la France après 1871. Le modèle revanchiste barrésien est donc transposable dans l’Allemagne vaincue et humiliée. Ensuite, peu enclin à accepter un travail politique conventionnel, Jünger est séduit, comme Barrès avant lui, par le Général Boulanger, l’homme qui, écrit-il, « ouvre énergiquement la fenêtre, jette dehors les bavards et laisse entrer l’air pur ». Chez Barrès, Ernst Jünger ne retrouve pas seulement les clefs d’une métapolitique de la revanche ou un idéal de purification violente de la vie politique, façon Boulanger. Il y a derrière cette réception de Barrès une dimension mystique, concentrée dans un ouvrage qu’Ernst Jünger avait déjà lu au Lycée : Du sang, de la volupté et de la mort. Il en retient la nécessité d’une ivresse orgiaque, qui ne craint pas le sang, dans toute démarche politique saine, c’est-à-dire dans le contexte de l’époque, de toute démarche politique non libérale, non bourgeoise.

Mais ce qui fait de Jünger un « nationaliste » dans les années 1920, c’est la lecture de Maurice Barrès. Pourquoi ? Avant la Grande Guerre, on était conservateur (mais non révolutionnaire !). Désormais, avec le mythe du sang, chanté par Barrès, on devient un révolutionnaire nationaliste. Le vocable, plutôt nouveau aux débuts de la république de Weimar, indique une radicalisation politique et esthétique qui rompt avec les droites conventionnelles. L’Allemagne, entre 1918 et 1923, est dans la même situation désastreuse que la France après 1871. Le modèle revanchiste barrésien est donc transposable dans l’Allemagne vaincue et humiliée. Ensuite, peu enclin à accepter un travail politique conventionnel, Jünger est séduit, comme Barrès avant lui, par le Général Boulanger, l’homme qui, écrit-il, « ouvre énergiquement la fenêtre, jette dehors les bavards et laisse entrer l’air pur ». Chez Barrès, Ernst Jünger ne retrouve pas seulement les clefs d’une métapolitique de la revanche ou un idéal de purification violente de la vie politique, façon Boulanger. Il y a derrière cette réception de Barrès une dimension mystique, concentrée dans un ouvrage qu’Ernst Jünger avait déjà lu au Lycée : Du sang, de la volupté et de la mort. Il en retient la nécessité d’une ivresse orgiaque, qui ne craint pas le sang, dans toute démarche politique saine, c’est-à-dire dans le contexte de l’époque, de toute démarche politique non libérale, non bourgeoise.  L’abandon des positions tranchées des années 1918-1933 provient certes de l’âge : Ernst Jünger a 50 ans quand le III° Reich s’effondre dans l’horreur. Il vient aussi du choc terrible que fut la mort au combat de son fils Ernstl dans les carrières de marbre de Carrare en Italie. Au moment d’écrire La Paix, Ernst Jünger, amer comme la plupart de ses compatriotes au moment de la défaite, constate : « Après une défaite pareille, on ne se relève pas comme on a pu se relever après Iéna ou Sedan. Une défaite de cette ampleur signifie un tournant dans la vie de tout peuple qui la subit ; dans cette phase de transition non seulement d’innombrables êtres humains disparaissent mais aussi et surtout beaucoup de choses qui nous mouvaient au plus profond de nous-mêmes ». Contrairement aux guerres précédentes, la deuxième guerre mondiale a porté la puissance de destruction des belligérants à son paroxysme, à des dimensions qu’Ernst Jünger qualifie de « cosmiques », surtout après l’atomisation des villes japonaises d’Hiroshima et de Nagasaki. Notre auteur prend conscience que cette démesure destructrice n’est plus appréhendable par les catégories politiques usuelles : de ce fait, nous entrons dans l’ère de la posthistoire. La défaite du III° Reich et la victoire des alliés (anglo-saxons et soviétiques) ont rendu impossible la poursuite des trajectoires historiques héritées du passé. Les moyens techniques de donner la mort en masse, de détruire des villes entières en quelques minutes sinon en quelques secondes prouvent que la civilisation moderne, écrit le biographe Schwilk, « tend irrémédiablement à détruire tout ce qui relève de l’autochtonité, des traditions, des faits de vie organiques ». C’est l’âge posthistorique des « polytechniciens de la puissance » qui commencent partout, et surtout dans l’Europe ravagée, à formater le monde selon leurs critères.

L’abandon des positions tranchées des années 1918-1933 provient certes de l’âge : Ernst Jünger a 50 ans quand le III° Reich s’effondre dans l’horreur. Il vient aussi du choc terrible que fut la mort au combat de son fils Ernstl dans les carrières de marbre de Carrare en Italie. Au moment d’écrire La Paix, Ernst Jünger, amer comme la plupart de ses compatriotes au moment de la défaite, constate : « Après une défaite pareille, on ne se relève pas comme on a pu se relever après Iéna ou Sedan. Une défaite de cette ampleur signifie un tournant dans la vie de tout peuple qui la subit ; dans cette phase de transition non seulement d’innombrables êtres humains disparaissent mais aussi et surtout beaucoup de choses qui nous mouvaient au plus profond de nous-mêmes ». Contrairement aux guerres précédentes, la deuxième guerre mondiale a porté la puissance de destruction des belligérants à son paroxysme, à des dimensions qu’Ernst Jünger qualifie de « cosmiques », surtout après l’atomisation des villes japonaises d’Hiroshima et de Nagasaki. Notre auteur prend conscience que cette démesure destructrice n’est plus appréhendable par les catégories politiques usuelles : de ce fait, nous entrons dans l’ère de la posthistoire. La défaite du III° Reich et la victoire des alliés (anglo-saxons et soviétiques) ont rendu impossible la poursuite des trajectoires historiques héritées du passé. Les moyens techniques de donner la mort en masse, de détruire des villes entières en quelques minutes sinon en quelques secondes prouvent que la civilisation moderne, écrit le biographe Schwilk, « tend irrémédiablement à détruire tout ce qui relève de l’autochtonité, des traditions, des faits de vie organiques ». C’est l’âge posthistorique des « polytechniciens de la puissance » qui commencent partout, et surtout dans l’Europe ravagée, à formater le monde selon leurs critères.

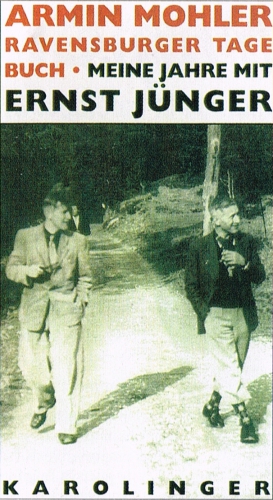

C’est évidemment une rupture non pas tant avec la RC (qui connait trop de facettes pour pouvoir être rejetée entièrement) mais avec ses propres postures nationales-révolutionnaires. Armin Mohler avait écrit le premier article louangeur sur Ernst Jünger dans Weltwoche en 1946. En septembre 1949, il devient le secrétaire d’Ernst Jünger avec pour première tâche de publier en Suisse une partie des journaux de guerre. Armin Mohler avait déjà achevé sa fameuse thèse sur la Révolution conservatrice, sous la supervision du philosophe existentialiste (modéré) et protestant Karl Jaspers, dont il avait retenu une idée cardinale : celle de « période axiale » de l’histoire. Une période axiale fonde les valeurs pérennes d’une civilisation ou d’un grand espace géoreligieux. Pour Armin Mohler, très idéaliste, la RC, en rejetant les idées de 1789, du manchestérisme anglais et de toutes les autres idées libérales, posait les bases, à la suite de l’idée d’amor fati formulée par Nietzsche, d’une nouvelle batterie de valeurs appelées, moyennant les efforts d’élites audacieuses, à régénérer le monde, à lui donner de nouvelles assises solides. Les idées exprimées par Ernst Jünger dans les revues nationales-révolutionnaires des années 20 et dans le Travailleur de 1932 étant les plus « pures », les plus épurées de tout ballast passéiste et de toutes compromissions avec l’un ou l’autre aspect du panlibéralisme du « stupide XIX° siècle » (Daudet !), il fallait qu’elles triomphent dans la posthistoire et qu’elles ramènent les peuples européens dans les dynamismes ressuscités de leur histoire. La pérennité de ces idées fondatrices de nouvelles tables de valeurs balaierait les idées boiteuses des vainqueurs soviétiques et anglo-saxons et dépasserait les idées trop caricaturales des nationaux-socialistes.

C’est évidemment une rupture non pas tant avec la RC (qui connait trop de facettes pour pouvoir être rejetée entièrement) mais avec ses propres postures nationales-révolutionnaires. Armin Mohler avait écrit le premier article louangeur sur Ernst Jünger dans Weltwoche en 1946. En septembre 1949, il devient le secrétaire d’Ernst Jünger avec pour première tâche de publier en Suisse une partie des journaux de guerre. Armin Mohler avait déjà achevé sa fameuse thèse sur la Révolution conservatrice, sous la supervision du philosophe existentialiste (modéré) et protestant Karl Jaspers, dont il avait retenu une idée cardinale : celle de « période axiale » de l’histoire. Une période axiale fonde les valeurs pérennes d’une civilisation ou d’un grand espace géoreligieux. Pour Armin Mohler, très idéaliste, la RC, en rejetant les idées de 1789, du manchestérisme anglais et de toutes les autres idées libérales, posait les bases, à la suite de l’idée d’amor fati formulée par Nietzsche, d’une nouvelle batterie de valeurs appelées, moyennant les efforts d’élites audacieuses, à régénérer le monde, à lui donner de nouvelles assises solides. Les idées exprimées par Ernst Jünger dans les revues nationales-révolutionnaires des années 20 et dans le Travailleur de 1932 étant les plus « pures », les plus épurées de tout ballast passéiste et de toutes compromissions avec l’un ou l’autre aspect du panlibéralisme du « stupide XIX° siècle » (Daudet !), il fallait qu’elles triomphent dans la posthistoire et qu’elles ramènent les peuples européens dans les dynamismes ressuscités de leur histoire. La pérennité de ces idées fondatrices de nouvelles tables de valeurs balaierait les idées boiteuses des vainqueurs soviétiques et anglo-saxons et dépasserait les idées trop caricaturales des nationaux-socialistes.  Armin Mohler veut convaincre le maître de reprendre la lutte. Mais Jünger vient de publier Le Mur du Temps, dont la thèse centrale est que l’ère de l’humanité historique, plongée dans l’histoire et agissant en son sein, est définitivement révolue. Dans La Paix, Ernst Jünger évoquait encore une Europe réunifiée dans la douleur et la réconciliation. Au seuil d’une nouvelle décennie, en 1960, les « empires nationaux » et l’idée d’une Europe unie ne l’enthousiasment plus. Il n’y a plus d’autres perspectives que celle d’un « Etat universel », titre d’un nouvel ouvrage. L’humanité moderne est livrée aux forces matérielles, à l’accélération sans frein de processus qui visent à se saisir de la Terre entière. Cette fluidité planétaire, critiquée aussi par Carl Schmitt, dissout toutes les catégories historiques, toutes les stabilités apaisantes. Les réactiver n’a donc aucune chance d’aboutir à un résultat quelconque. Pour parfaire un programme national-révolutionnaire, comme les frères Jünger en avaient imaginé, il faut que les volontés citoyennes et soldatiques soient libres. Or cette liberté s’est évanouie dans tous les régimes du globe. Elle est remplacée par des instincts obtus, lourds, pareils à ceux qui animent les colonies d’insectes.

Armin Mohler veut convaincre le maître de reprendre la lutte. Mais Jünger vient de publier Le Mur du Temps, dont la thèse centrale est que l’ère de l’humanité historique, plongée dans l’histoire et agissant en son sein, est définitivement révolue. Dans La Paix, Ernst Jünger évoquait encore une Europe réunifiée dans la douleur et la réconciliation. Au seuil d’une nouvelle décennie, en 1960, les « empires nationaux » et l’idée d’une Europe unie ne l’enthousiasment plus. Il n’y a plus d’autres perspectives que celle d’un « Etat universel », titre d’un nouvel ouvrage. L’humanité moderne est livrée aux forces matérielles, à l’accélération sans frein de processus qui visent à se saisir de la Terre entière. Cette fluidité planétaire, critiquée aussi par Carl Schmitt, dissout toutes les catégories historiques, toutes les stabilités apaisantes. Les réactiver n’a donc aucune chance d’aboutir à un résultat quelconque. Pour parfaire un programme national-révolutionnaire, comme les frères Jünger en avaient imaginé, il faut que les volontés citoyennes et soldatiques soient libres. Or cette liberté s’est évanouie dans tous les régimes du globe. Elle est remplacée par des instincts obtus, lourds, pareils à ceux qui animent les colonies d’insectes. ![AM_mohler-j-nger-briefe52a2b554d7f4d_720x600[1]_600x600.jpg](http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/media/02/00/3993534085.jpg) La ND française émerge sur la scène politico-culturelle parisienne à la fin des années 60. Ernst Jünger y apparait d’abord sous la forme d’une plaquette du GRECE due à la plume de Marcel Decombis. La RC, plus précisément la thèse de Mohler, est évoquée par Giorgio Locchi dans le n°23 de Nouvelle école. A partir de ces textes éclot une réception diverse et hétéroclite : les textes de guerre pour les amateurs de militaria ; les textes nationaux-révolutionnaires par bribes et morceaux (peu connus et peu traduits !) chez les plus jeunes et les plus nietzschéens ; les journaux chez les anarques silencieux, etc. De Mohler, la ND hérite l’idée d’une alliance planétaire entre l’Europe et les ennemis du duopole de Yalta d’abord, de l’unipolarité américaine ensuite. C’est là un héritage direct des politiques et alliances alternatives suggérées sous la République de Weimar, notamment avec le monde arabo-musulman, la Chine et l’Inde. Par ailleurs, Armin Mohler réhabilite Georges Sorel de manière beaucoup plus explicite et profonde que la ND française. En Allemagne, Mohler reçoit un tiers de la surface de la revue Criticon, dirigée à Munich par le très sage et très regretté Baron Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing. Aujourd’hui, cet héritage mohlerien est assumé par la maison d’édition Antaios et la revue Sezession, dirigées par Götz Kubitschek et son épouse Ellen Kositza.

La ND française émerge sur la scène politico-culturelle parisienne à la fin des années 60. Ernst Jünger y apparait d’abord sous la forme d’une plaquette du GRECE due à la plume de Marcel Decombis. La RC, plus précisément la thèse de Mohler, est évoquée par Giorgio Locchi dans le n°23 de Nouvelle école. A partir de ces textes éclot une réception diverse et hétéroclite : les textes de guerre pour les amateurs de militaria ; les textes nationaux-révolutionnaires par bribes et morceaux (peu connus et peu traduits !) chez les plus jeunes et les plus nietzschéens ; les journaux chez les anarques silencieux, etc. De Mohler, la ND hérite l’idée d’une alliance planétaire entre l’Europe et les ennemis du duopole de Yalta d’abord, de l’unipolarité américaine ensuite. C’est là un héritage direct des politiques et alliances alternatives suggérées sous la République de Weimar, notamment avec le monde arabo-musulman, la Chine et l’Inde. Par ailleurs, Armin Mohler réhabilite Georges Sorel de manière beaucoup plus explicite et profonde que la ND française. En Allemagne, Mohler reçoit un tiers de la surface de la revue Criticon, dirigée à Munich par le très sage et très regretté Baron Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing. Aujourd’hui, cet héritage mohlerien est assumé par la maison d’édition Antaios et la revue Sezession, dirigées par Götz Kubitschek et son épouse Ellen Kositza.

En 1967, Louis Dumont publiait un ouvrage, devenu un classique aujourd'hui, consacré à l'étude du système des castes en Inde. Cette vaste enquête, fort novatrice à l'époque, était le point de départ d'une comparaison méthodique entre les cultures traditionnelles et cette spécificité dans l'histoire des cultures que représente l'idéologie moderne occidentale. Pour aider à mieux comprendre le cheminement particulier qui a abouti au monde moderne, Dumont était enclin à souligner l'importance de la conception que les sociétés ont de la place de l'individu à l'intérieur d'elles-mêmes. Pour cela, il créait une distinction majeure entre les sociétés de type holiste et les sociétés de type individualiste. Par holiste, il entendait les représentations qui privilégient la totalité, le corps social avant de mettre en avant le rôle des individus, et, par le second terme, les idées qui posent l'individu comme premier par rapport au tout social. La comparaison entre le jeu des castes, la hiérarchie qu'il suppose et l'univers de l'individu, les notions de liberté, d'égalité présentait un éclairage nouveau de la situation moderne. Il poursuivait son enquête avec la publication, en 1977, d'Homo

En 1967, Louis Dumont publiait un ouvrage, devenu un classique aujourd'hui, consacré à l'étude du système des castes en Inde. Cette vaste enquête, fort novatrice à l'époque, était le point de départ d'une comparaison méthodique entre les cultures traditionnelles et cette spécificité dans l'histoire des cultures que représente l'idéologie moderne occidentale. Pour aider à mieux comprendre le cheminement particulier qui a abouti au monde moderne, Dumont était enclin à souligner l'importance de la conception que les sociétés ont de la place de l'individu à l'intérieur d'elles-mêmes. Pour cela, il créait une distinction majeure entre les sociétés de type holiste et les sociétés de type individualiste. Par holiste, il entendait les représentations qui privilégient la totalité, le corps social avant de mettre en avant le rôle des individus, et, par le second terme, les idées qui posent l'individu comme premier par rapport au tout social. La comparaison entre le jeu des castes, la hiérarchie qu'il suppose et l'univers de l'individu, les notions de liberté, d'égalité présentait un éclairage nouveau de la situation moderne. Il poursuivait son enquête avec la publication, en 1977, d'Homo  Humboldt, dans ses écrits, met en forme la réponse allemande aux idées révolutionnaires : l'individu de la

Humboldt, dans ses écrits, met en forme la réponse allemande aux idées révolutionnaires : l'individu de la We are soldiers because we refuse the reformist tinkering of the dominant system, which — through its electoral and party committees, its partisan venalities, and its parliamentary charade — endeavors to ensure the self-regulation and recycling of the corrupt elites controlling the existing plutocratic system.

We are soldiers because we refuse the reformist tinkering of the dominant system, which — through its electoral and party committees, its partisan venalities, and its parliamentary charade — endeavors to ensure the self-regulation and recycling of the corrupt elites controlling the existing plutocratic system.