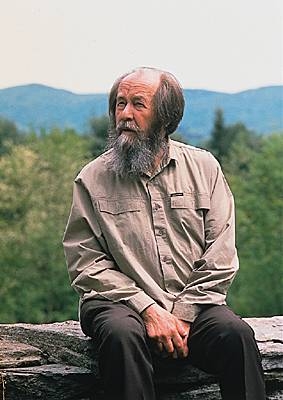

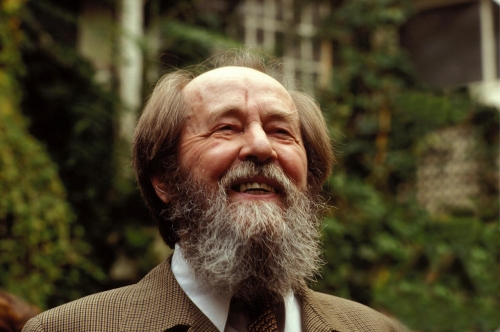

It’s striking how cherry-picking can hone the pen of a propagandist and disguise malice behind a veneer of reason. Jewish writer Cathy Young provides excellent examples of this all throughout her December 2018 Quillette article, “Solzhenitsyn: The Fall of a Prophet. [2]” Published shortly after Solzhenitsyn’s 100th birthday, the article’s point, essentially, is to tarnish the reputation of a great man in order to steer discourse away from aspects of his work which the current zeitgeist finds problematic. Her shoddy, dishonest treatment of Solzhenitsyn resembles Soviet-styled political revisionism, and it stinks, frankly, of character assassination. She doesn’t merely disagree with some of Solzhenitsyn’s positions and explain why (which would have been perfectly fine); rather, because she’s uncomfortable with some of his positions, she endeavors to dig up everything negative or embarrassing she can about the man in order to discredit him, both morally and intellectually.

Why bother to read Solzhenitsyn at all now that Cathy Young has stabbed him full of holes with her rapier-sharp pen?

Young kicks the article off by paying homage to Solzhenitsyn’s life and works with obligatory, Wikipedia-style platitudes and spices them with anecdotes from her childhood in the Soviet Union. This takes up a few paragraphs and rings true enough. However, this is completely forgotten by the time Young gets to what she really wants to talk about: Solzhenitsyn beyond his role as heroic, anti-Communist dissident.

This role, I think we can all agree, constitutes the vast majority of his legacy. The bravery, tenacity, and clarity of thought that this man demonstrated at a time when political repression was as bad as it could possibly be was frankly inhuman – in a good way. One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich has proven to be an immortal and poignant sketch of life in a Soviet labor camp. Many of his early short stories (“Matryona’s House” and “We Never Make Mistakes,” in particular) as well as his 1968 novel Cancer Ward were equally brilliant. His speeches and essays from the Soviet period are clear, consistent, forthright, and prescient (“The Smatterers” from 1974 and his Warning to the West collection from 1976 are among my favorites). And The Gulag Achipelago speaks for itself as one of the greatest and most consequential non-fiction works of the twentieth century. One can review David Mahoney’s centennial eulogy [3] for Solzhenitsyn for more.

Young, however, cares to ding Solzhenitsyn for his exile-era and post-Soviet writings which concern, among other things, Russian identity, nationalism, Christianity, and the Jewish Question. Consequently, Solzhenitsyn has proven himself to be quite the gadfly in the ointment for our anti-white, globalist elites who believe that all of these things are bad, bad, bad and worry about their making a comeback in the age of Trump:

In 2018, Solzhenitsyn’s hostility toward Western-style democracy and secular universalist liberalism may find much broader resonance than it did in his twilight years. When Solzhenitsyn asserted in a 2006 interview with Moscow News that “present-day Western democracy is in a grave crisis,” that statement could be easily dismissed as a maverick’s wishful fantasy. Today, it sounds startlingly prescient. In an age when nationalist/populist movements are on the rise in Europe and the Americas and the liberal project is increasingly seen as outdated, Solzhenitsyn might be seen as a man ahead of his time.

For Young, of course, this is a bad thing:

But one could also make a compelling argument for the opposite: that Solzhenitsyn’s life and career are a case study in the perils of choosing the path of nationalism and anti-liberalism, a path that ultimately led him to some dark places.

So, to prevent as many people as possible from drawing inspiration from this great man, it’s time to start taking him down. But how to take down a man of Solzhenitsyn’s titanic stature? That’s a problem, isn’t it? Well, Cathy Young decides to solve it by cherry picking elements of the man’s life to draw an ugly, mean-spirited caricature of him. She’s done this before [4]. She also relies on her audience to either not read up on Solzhenitsyn to fact-check her sloppy scholarship or to not understand Russian in case they might do so.

She begins by citing and interpreting his 1983 essay “Our Pluralists.” This essay doesn’t seem to be translated into English on the Internet; Young provides a link to the original Russian [5], and I found a partially translated version here [6]. Oddly, Young describes only how this essay offended other dissidents and doesn’t directly critique it herself.

Young:

To Solzhenitsyn, the worship of pluralism inevitably led to moral relativism and loss of universal values, which he believed had “paralyzed” the West. He also warned that if the communist regime in Russia were to fall, the “pluralists” would rise, and “their thousand-fold clamor will not be about the people’s needs . . . not about the responsibilities and obligations of each person, but about rights, rights, rights” – a scenario that, in his view, could result only in another national collapse.

Yes, and . . .? How is his incorrect? It seems as if Solzhenitsyn had a crystal ball back in 1983, and not just for Russia. In this case, pluralism for Solzhenitsyn meant pluralism of ideas, not racial or ethnic pluralism. Relativism, essentially. Solzhenitsyn was basically arguing for the acceptance of an objective Truth, albeit from within an uncompromisingly traditionalist and Christian framework.

Solzhenitsyn:

Of course, variety adds color to life. We yearn for it. We cannot imagine life without it. But if diversity becomes the highest principle, then there can be no universal human values, and making one’s own values the yardstick of another person’s opinions is ignorant and brutal. If there is no right and wrong, what restraints remain? If there is no universal basis for it there can be no morality. ‘Pluralism’ as a principle degenerates into indifference, superficiality, it spills over into relativism, into tolerance of the absurd, into a pluralism of errors and lies.

According to the essay, Solzhenitsyn has no problem with pluralism per se as long as these pluralistic ideas are constantly compared “so as to discover and renounce our mistakes.” In this regard, his framework is as much Classical as it is Christian.

One can disagree, of course, but there is absolutely nothing that is morally or intellectually objectionable about any of this. Yet because Young can dredge up a handful of names who opposed Solzhenitsyn’s Christian dogmatism or wrung their hands over his preference for Duty over Freedom, she seems to think that that makes her subject look bad. It doesn’t. These critics accused him of groupthink and labeled him a “true Bolshevik” – ridiculous claims repudiated by the essay itself. All Young can really say is that Solzhenitsyn had opponents who disagreed with him and smeared him for it. So what? Name a great man who didn’t.

Young also attempts to throw a wet blanket on Solzhenitsyn’s not-so-triumphant return to Russia in the mid-1990s. According to Young, the Russian public didn’t seem terribly interested in him. His several-thousand-page epic The Red Wheel and other later works didn’t sell terribly well. His talk show wasn’t a hit. Not many young people in Russia read him anymore, or have even heard of the Gulag system. Only a few hundred people showed up at his funeral in 2008. Again, so what? Apparently, Young believes that because Solzhenitsyn’s star power began to fade when he was in his late 70s, his legacy began to fade as well. Can she not see how desperate and superficial this tack really is?

She also takes him to task for supporting Vladimir Putin in the 2000s and inviting him to his home in 2007 – when Solzhenitsyn was eighty-nine years old. Leaving aside any charity we would wish to grant an octogenarian Gulag and cancer survivor, Young would have us believe that “the man who exposed the full horror of Stalin’s rule had nothing to say about the creeping rehabilitation of Stalin on Putin’s watch.”

Did Vladimir Putin starve twelve million people to death and wrongfully imprison and execute tens of millions more without anyone knowing about it, except Cathy Young? Sure, Putin is an authoritarian, and it’s impossible to go to bat for everything he does. But to equate him in any way with Stalin is pure idiocy. This is real “Trump is literally Hitler” territory and serves only to silence debate, not encourage it. How could the editors of Quillette not see this?

Further, by basing most of her critiques on Solzhenitsyn’s later works and statements, Young makes this “fall of a prophet” business seem like it’s something new – as if the man was righteous for a while and then lost it once he started knocking on pluralism and giving a thumbs-up to authoritarianism. By this point, she tells us, “Solzhenitsyn could no longer be seen as a champion of freedom and justice.” She omits mentioning that Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn had supported authoritarian rule since at least 1973. His essay “As Breathing and Consciousness Return” goes into eloquent detail on the virtues of such systems, provided that the autocrats are bound by “higher values.” In the past, this meant God. With Putin, it means the destiny of the Russian people. It is entirely consistent thirty-five years later for a Russian patriot like Solzhenitsyn to prefer Putin to the corruption and chaos of the Yeltsin era, in which Russia was at the mercy of corrupt oligarchs and mafioso such as Boris Berezovsky and Vladimir Gusinsky. According to Paul Klebnikov, in his 2000 work Parrain du Kremlin, Boris Berezovsky et Le Pillage de la Russie, there were 29,200 murders in Russia in 1993 alone (by 2013, according Infogalactic, that figure was down to 12,785 [7]). The number of murders in Russia increased eight hundred percent from 1987 to 1993. 1994 saw 185 police officers die in the line of duty. Yet Cathy Young wishes that we concern ourselves with Putin’s “creeping rehabilitation of Stalin.”

The crux of her dissertation involves, of course, Solzhenitsyn’s honest take on the Jewish Question – but she takes pains to paint him as an equal opportunity bigot who focused his slavophilic ire on unchosen peoples as well. This she calls “a streak of prejudice in his work.” Here is Cathy Young at her most insidious:

In his 1973 essay, “Repentance and Self-Limitation As Categories of National Life,” he suggested Russians’ moral responsibility for Soviet crimes against Hungary and Latvia was somewhat mitigated by the fact that Hungarian and Latvian nationals were actively involved in the Red Terror after the Russian revolution, while the shame of the ethnic cleansing of Crimean Tatars was lessened by their status as “chips off the Horde,” the Mongol khanate that violently subjugated Russia in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. And, while Solzhenitsyn often asserted that his Russian patriotism was grounded in respect for the self-determination of other nations, he was vehemently hostile to Ukrainian and Belarussian independence.

Let’s break this down carefully, since Young’s dishonesty is astonishing. In my translation of “Repentance and Self-Limitation in the Life of Nations,” Solzhenitsyn stresses often how Russians, as a people, need to show penance for their sins, not just against themselves but against other peoples. He takes a position that is as respectful and conciliatory as possible towards foreign groups while still being nationalistic:

It is impossible to imagine a nation which throughout the course of its whole existence has no cause for repentance. Every nation without exception, however persecuted, however cheated, however flawlessly righteous it feels itself to be today has certainly at one time or another contributed its share of inhumanity, injustice, and arrogance.

Solzhenitsyn then outlines a list of transgressions for which the Russians should do penance, despite how they themselves had suffered enormously in the twentieth century. “My view is that if we err in our repentance,” he states, “it should be on the side of exaggeration, giving others the benefit of the doubt. We should accept in advance that there is no neighbor to whom we bear no guilt.”

So does this sound like a “streak of prejudice”? If anything, it’s prejudicial against Russians. There’s more. Solzhenitsyn understood that penance works only if it goes both ways. He asks, “How can we possibly rise above all this, except by mutual repentance?” [emphasis mine]. His position regarding the Latvians and Hungarians is that they repented little for what they did to Russians “in the cellars of the Cheka and the backyards of Russian villages.” So why should Russians shed many tears for them in return? Same with the Crimean Tatars, who never showed much remorse for the pain they inflicted upon the Russians over the course of centuries. Note also how Young downplays Tatar sins by casting them into the distant past of the “thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.” She neglects to mention that some of their worst transgressions occurred much more recently. According to M. A. Khan in his 2009 work Islamic Jihad, the Crimean Tatars captured, enslaved, and sold to the Ottoman Empire anywhere between 1.75 and 2.5 million Ukrainians, Poles, and Russians between 1450 and 1700. That might be worth a sorry or two, wouldn’t it? Suddenly, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn is not quite as bigoted as Cathy Young would have him seem.

Regarding the man’s opinions on Belorussian and Ukrainian independence, Young again mischaracterizes him. Solzhenitsyn was speaking up for the persecuted kulaks and the victims of the 1930s Ukrainian terror famine as early as The Gulag Archipelago (Volume 1, Part 1, Chapter 2) and later in 2003’s Two Hundred Years Together (Volume 2, Chapter 19). His numbers from the latter work (15 million killed) roughly coincide with Robert Conquest’s from his 1986 work Harvest of Sorrow (14.5 million killed). By stating that Solzhenitsyn was “vehemently hostile” to Ukrainian independence, Young was implying that her subject was chauvinistically contemptuous of the nationalist ambitions of these nations. That’s just not true. In reality, Solzhenitysn envisioned a pan-Slavic Russia in which Russia would keep Belarus and only the eastern half of Ukraine. In a 1994 interview [8], Solzhenitsyn had this to say about it:

As a result of the sudden and crude fragmentation of the intermingled Slavic peoples, the borders have torn apart millions of ties of family and friendship. Is this acceptable? The recent elections in Ukraine, for instance, clearly show the [Russian] sympathies of the Crimean and Donets populations. And a democracy must respect this.

I myself am nearly half Ukrainian. I grew up with the sounds of Ukrainian speech. I love her culture and genuinely wish all kinds of success for Ukraine – but only within her real ethnic boundaries, without grabbing Russian provinces.

Does this sound “vehemently hostile?” I will admit his brief denunciation [9] of the Ukrainian genocide claim from April 2008 came across as cranky. But he was 89 at the time and all of four months away from the grave! Who wouldn’t come across as a little cranky under such circumstances?

Further, Young’s source [10] for the “vehemently hostile” smear is riddled with contradictions. It faults Solzhenitsyn for wanting Russia to let go of non-Slavic republics like Armenia and Kyrgyzstan (thereby respecting their nationalism) and then criticizes him for wanting to keep Belarus and parts of Ukraine (thereby disrespecting their nationalism). This is unreasonable since it puts Solzhenitsyn in a lose-lose position. In her article, Young claims that Solzhenitsyn’s nationalist path “ultimately led him to some dark places.” Well, okay, but if nationalism is bad, then why doesn’t she slam Belarus, Ukraine, Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, and all the other republics for their nationalist agendas? Why is it only Russian nationalism that leads to the path to darkness?

Note also how Young never cites instances in Solzhenitsyn’s writing in which he shows favoritism towards other groups. In Cancer Ward, the main character Kostoglotov describes how he sided in a fight with some Japanese prisoners against Russian prisoners because the Russians were behaving barbarically and deserved it. In “the Smatterers” he writes in glowing terms about the birth of Israel. His 1993 Vendée Uprising address was a veritable love letter to the French. And let’s not forget the downright tenderness he shows towards the Estonians in Volume 1, Part 1, Chapter 5 of The Gulag Archipelago. Of course, I could go on.

As for the Jews, we can’t expect to do Solzhenitsyn’s treatment of them any justice in such a short article. We can, however, condense it into two main segments: his fiction and his non-fiction. In his fiction, his tendency was to portray Jews in a somewhat negative light, it’s true. Great examples include Lev Rubin and Isaak Kagan from In the First Circle, who seem sympathetic but ultimately defend the evils of Communism. His treatment of Jews in his early play The Love-Girl and the Innocent reach Shylock/Fagin levels of stereotype (although Solzhenitsyn based one of these characters on a particularly vile Jew in real life named Isaak Bershader, who also appears in Volume 2, Part 3, Chapter 8 of The Gulag Archipelago in an unforgettable scene in which he crushes the spirit of a strong and beautiful Russian woman before coercing her to become his mistress). Then there’s the expanded version of August 1914, which included a chapter dealing with Dmitri Bogrov, the Jewish radical who assassinated the great Russian Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin in 1911.

According to Young, Solzhenitsyn portrayed Bogrov “with no factual basis, as a Russia-hating Jewish avenger.” I would have to do a great deal of research to verify this claim, of course. However, I don’t trust Cathy Young. The deceptions and smears in her article should prevent anyone from trusting her. Furthermore, Bogrov did assassinate Stolypin, and Stolypin was a great man. Would Young rather Solzhenitsyn portray Bogrov as a hero? Is it too much of a stretch for us to believe Bogrov harbored an ethnic grudge against Russia and Russians? He wouldn’t have been the first. Kevin MacDonald has given us an entire body of work demonstrating exactly how some influential Jews harbor deep and irrational resentment towards white gentiles. So why not Dmitri Bogrov?

I have read the Bogrov passages in August 1914. Young’s take on them is jaundiced, to say the least. The author paints a moving portrait of a mentally disturbed, rigid-minded, radically-inclined, highly-informed, and ethnically-obsessed young man. How does that not fit the bill for a Jewish anarchist from a century ago? How is this any different from the way in which Solzhenitsyn portrayed a whole host of Russian authority figures in his Red Wheel opus as incorrigibly incompetent, cowardly, vain, irresponsible, and self-centered? Does this make him as anti-Russian as he is anti-Semitic? Or maybe just honest?

And speaking of honesty, let’s look at how Cathy Young most dishonestly doesn’t mention Solzhenitsyn’s positive Jewish characters, such as Ilya Arkhangorodsky, also from August 1914, and Susanna Korzner from March 1917.

As for his non-fiction, people can argue whether Solzhenitsyn unfairly singled out Jewish Gulag administrators in The Gulag Archipelago. But that’s small potatoes compared to his opus Two Hundred Years Together. On this account, Young actually does a fairly evenhanded job of assessing her subject. Even the Jews can’t decide on whether Solzhenitsyn was an anti-Semite, and many of them who actually knew him personally deny it, since Solzhenitsyn’s behavior towards them was always impeccable. Young dutifully presents both sides and links to a well-balanced Front Page symposium [11] before tilting her conclusion in favor of anti-Semitism. That’s her right, of course.

My take is a little different. I say that Solzhenitsyn acted in good faith when writing Two Hundred Years Together. He may or may not have made mistakes in his work, but I say he presented the gentile side of the argument pretty well. It is a side that rarely sees the light of day given how prolific Jews are in portraying their end of the struggle and how influential they are in suppressing literature they find threatening. Why else go after people like Pat Buchanan and Joe Sobran? Why else see to it that pro-white writers and activists like MacDonald and Jared Taylor get thoroughly marginalized? Why else suppress Holocaust denial and revisionist literature? Why else create a forbidding atmosphere for the publication of Two Hundred Years Together in English?

There’s more. Jewish writers like Cathy Young seem to suffer so much from whites-on-the-brain that they fail to recognize the abuses of their own kind when writing about gentiles. She should read Robert Wistrich, Bernard Lewis, Deborah Lipstadt, and other Jewish authors when they write about anti-Semitism and then ask herself if they were as being as sympathetic to gentiles and Solzhenitsyn was to Jews in Two Hundred Years Together. Having read many of them, I would say usually not. Solzhenitsyn lists righteous and innocent Jews by name in that work. In Chapter 25, he calls for “sincere and mutual understanding between Russians and Jews, if only we would not shut it out by intolerance and anger.”

He states further:

I invite all, including Jews to abandon this fear of bluntness, to stop perceiving honesty as hostility. We must abandon it historically! Abandon it forever!

In this book, I call a spade a spade. And at no time do I feel that in doing so it is being hostile to the Jews. I have written more sympathetically than many Jews write about Russians.

The purpose of this book, reflected even in its title, is this: we should understand each other, we should recognize each other’s standpoint and feelings. With this book, I want to extend a handshake of understanding – for all our future. But we must do so mutually!

Does this sound like it was written by an anti-Semite? Maybe it does to someone as dishonest and as blinkered as Cathy Young. Maybe it does to someone who wishes to enforce a program of mandatory philo-Semitism among the goyim. But to everyone else, it just seems like it was written by the same man who thirty years earlier told Russians they should “err . . . on the side of exaggeration” when it comes to repentance . . . but only if that repentance is mutual.

Does this sound like it was written by an anti-Semite? Maybe it does to someone as dishonest and as blinkered as Cathy Young. Maybe it does to someone who wishes to enforce a program of mandatory philo-Semitism among the goyim. But to everyone else, it just seems like it was written by the same man who thirty years earlier told Russians they should “err . . . on the side of exaggeration” when it comes to repentance . . . but only if that repentance is mutual.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was a great man and a great writer for many reasons, not least because he was honest and consistent. It’s a shame that some people today feel so threatened by him that they resort to underhanded smear pieces to discredit him and hound him out of public discourse. Undoubtedly, they fear not just his nationalism but his ethnonationalism. This may not have been terribly in vogue during the last years of his life, but it is trending that way now, especially for white people. Cathy Young was absolutely correct about that and about how Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was a man ahead of his time. She contrives a number of arguments to make it seem as if we’re witnessing the fall of a prophet, but in reality, we are only witnessing his rise.

Spencer J. Quinn is a frequent contributor to Counter-Currents and the author of the novel White Like You [12].

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

L’Etat nous détruira (Tocqueville, Nietzsche, etc.). Voici ce qu’il aurait dû être l’Etat :

L’Etat nous détruira (Tocqueville, Nietzsche, etc.). Voici ce qu’il aurait dû être l’Etat : Et Novalis d’attendre une résurrection de l’Europe :

Et Novalis d’attendre une résurrection de l’Europe :

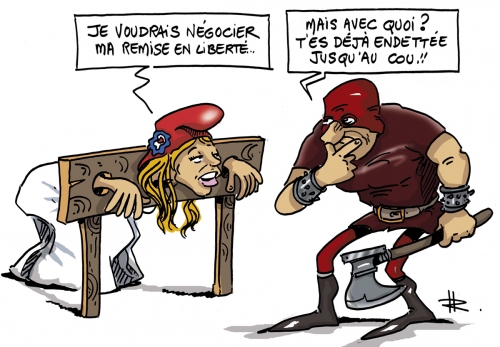

En réaction aux campagnes en faveur de l’annulation totale de la dette du tiers monde et aux critiques de l’initiative

En réaction aux campagnes en faveur de l’annulation totale de la dette du tiers monde et aux critiques de l’initiative