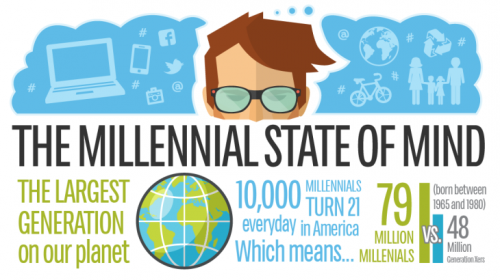

In a recent article at TAC, writer Alex Muresianu put into relief the difficulties that lie ahead for the GOP as it seeks to capture a larger chunk of the Millennial vote.

In the 2018 elections, voters between the ages of 18 and 29 voted for Democrats in House races by a margin of 35 points. Tellingly, Millennials who attended college were more likely to vote Democrat than those who didn’t. As a retired professor, I can attest to the immersion in leftist ideas that a college education, particularly in the humanities and social sciences, brings with it. But however we look at the demographic under consideration, the disparity in voting preferences cited by Muresianu remains quite noticeable.

Muresianu proposes that Republicans endeavor to reduce “income inequality” in part by making it easier to live in urban areas. Because of controls on who can build what in certain cities, which are invariably run by Democratic administrations, Millennials, who concentrate in those cities, are paying more for housing and rentals than they otherwise would. If more abundant and cheaper housing were available, those urban residents might reward the Republicans who helped bring this about by changing their party affiliations.

Pardon my skepticism. For one, people tend to make their electoral choices for cultural and sociological—not just material—reasons. Further, it seems unlikely that policies, even ones as popular as affordable urban housing, can shake political loyalties that run so deep.

Let’s look at non-economic factors. Black voters are not rushing to embrace Donald Trump because he improved their employment prospects (unemployment is at its lowest rate since 2006). As a bloc, black voters loathe the president and prefer Democrats who—though they might not be much help financially—still appeal to their view of themselves as an oppressed minority.

Democrats play up race and gender because it works as an electoral magnet. Muresianu and I may not like this situation (personally I detest it). But it is nonetheless a winning strategy. Millennials vote for the Left because they have been conditioned to do so by social media, educational institutions, and their peers. They are not likely to be turned away by a policy gimmick—one that could only be implemented, by the way, if Republicans capture municipal governments, a prize that the GOP will not likely be winning in the near future. (The bane of the GOP, Bill de Blasio of New York City, won 65.3 percent of the votes cast in his last mayoral race.)

This doesn’t necessarily hold in Europe, where some young people are more inclined to vote for the Right than they are here. In France, the Rassemblement National is building its base among Millennials; a similar trend can be seen at work among populist Right parties in Eastern Europe. In Hungary, the favorite political party among university students is the very far Right (I don’t use this term lightly) Jobbik Party. But there are also variables at work in Europe that have helped make the young more conservative: less urbanization in some countries than is the case here, a high degree of ethnic and racial homogeneity, and the persistence of traditional family and gender relations are all factors that counteract the cultural-political radicalization of young adults.

In the U.S., we may have reached a perfect storm for this radicalization, because very few of the countervailing forces that continue to operate in other societies are present here. This is not to even mention the giveaway programs (masquerading as “socialism”) that the Democrats have promised the young. How can Republicans match such largesse?

Moreover, a growing percentage of Millennial voters are multiracial and generally tend toward the Left. A study by the Brookings Institute in 2016 indicates that no more than 55 percent of those between 18 and 34 are white. It is hard to imagine that these non-white young voters, who are now solidly on the Left, will embrace Republican politicians because they promise to free up the urban rental and real estate markets.

Political and cultural loyalties may change among some Millennials but not because of the attraction of deregulation (except possibly for marijuana). These loyalties will change as certain groups within the leftist front start fighting each other. Why should straight white males continue to make common cause with black nationalists, feminists, and LGBT activists? Why should poor blacks go on supporting indefinitely the policy of rich leftist elites advocating virtually open borders? Being flooded with unskilled labor from other countries certainly doesn’t help the job situation in black communities.

The politics of victimology does have its limits and at some point may show wear. Hatred of white male Christian heterosexuals cannot keep a coalition going forever, particularly when this alliance of self-described victims reveals sharply competing interests and sensibilities. Of course, the Left’s coalition will not fall apart in the short run. But if some Millennials do eventually move towards the Right, what will draw them will not be the promise of cheaper lodgings. Something more dramatic will have to happen.

Paul Gottfried is Raffensperger Professor of Humanities Emeritus at Elizabethtown College, where he taught for 25 years. He is a Guggenheim recipient and a Yale Ph.D. He is the author of 13 books, most recently Fascism: Career of a Concept and Revisions and Dissents.

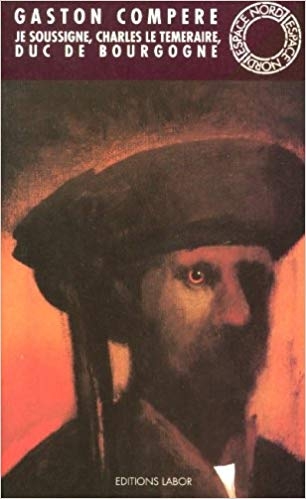

J'avais en mémoire le Charles le Téméraire décrit par Marcel Brion en 1977. Gaston Compère me le décrit sous un autre angle. Un angle que je préfère. Écrit à la première personne du singulier, Je soussigné, Charles le Téméraire, duc de Bourgogne est un roman tout comme Moi, Antoine de Tounens, roi de Patagonie de Jean Raspail est un roman Celui de Gaston Compère est aussi différent de la biographie de Marcel Brion, parue sous le titre Charles le Téméraire, que celui de Jean Raspail l’est de celle de Saint-Loup Le roi blanc des Patagons.Avec Mémoires d’Hadrien, Marguerite Yourcenar avait porté le roman biographique à sa perfection ; avec Je soussigné, Charles le Téméraire, duc de Bourgogne, Gaston Compère fait voler en éclats la biographie romanesque. Né en Wallonie en 1929, cet écrivain s’avère visionnaire. Il investit l’âme du Téméraire, qui n’aimait pas son nom et qui eût préféré celui de Charles le Hardi.

J'avais en mémoire le Charles le Téméraire décrit par Marcel Brion en 1977. Gaston Compère me le décrit sous un autre angle. Un angle que je préfère. Écrit à la première personne du singulier, Je soussigné, Charles le Téméraire, duc de Bourgogne est un roman tout comme Moi, Antoine de Tounens, roi de Patagonie de Jean Raspail est un roman Celui de Gaston Compère est aussi différent de la biographie de Marcel Brion, parue sous le titre Charles le Téméraire, que celui de Jean Raspail l’est de celle de Saint-Loup Le roi blanc des Patagons.Avec Mémoires d’Hadrien, Marguerite Yourcenar avait porté le roman biographique à sa perfection ; avec Je soussigné, Charles le Téméraire, duc de Bourgogne, Gaston Compère fait voler en éclats la biographie romanesque. Né en Wallonie en 1929, cet écrivain s’avère visionnaire. Il investit l’âme du Téméraire, qui n’aimait pas son nom et qui eût préféré celui de Charles le Hardi. Cela suffit peut-être mais je ne peux m’empêcher de citer ici quelques perles qui font à la fois comprendre l’esprit qui anima Charles le Téméraire et l’immense talent de Gaston Compère.

Cela suffit peut-être mais je ne peux m’empêcher de citer ici quelques perles qui font à la fois comprendre l’esprit qui anima Charles le Téméraire et l’immense talent de Gaston Compère.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

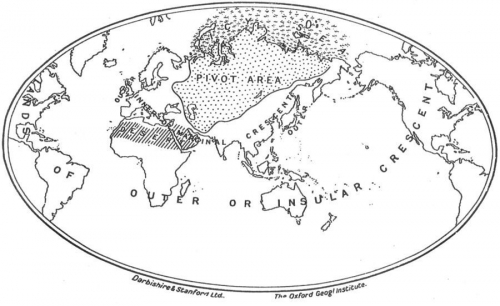

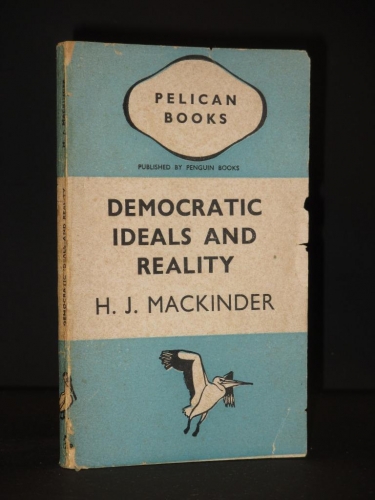

That key asset was the British Navy. For centuries, Britain had mostly relied on naval strength to win wars and maintain the balance of power in continental Europe. During the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), for instance, the British were undistinguished in ground combat, and yet they won big at sea, using their ships to snap up valuable French possessions in North America, Africa, and India.

That key asset was the British Navy. For centuries, Britain had mostly relied on naval strength to win wars and maintain the balance of power in continental Europe. During the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), for instance, the British were undistinguished in ground combat, and yet they won big at sea, using their ships to snap up valuable French possessions in North America, Africa, and India.