While France and England gave materialistic, anti-traditional expressions to the concept of “the people” that was taking shape since the French Revolution, German Idealism was a return to a spiritual, metaphysical direction. The German Revolution moved in a volkish direction, where the volk was seen as the basis of the state, and the notion of a volk-soul that guided the formation and development of nations became a predominant theme that came into conflict with the French bourgeois liberal-democratic ideals derived from Jacobinism. Fichte had laid the foundations of a German nationalism in 1807-1808 with his Addresses to the German Nation. Although like possibly all revolutionaries or radicals of the time, beginning under the impress of the French Revolution, by the time he had delivered his addresses to the German nation, he had already rejected Jacobinism. Johann Heder had previously sought to establish the concept of the volk-soul, and of each nation being guided by a spirit. This was a metaphysical conception of race, or more accurately volk, that preceded the biological arguments of the Frenchman Count Arthur de Gobineau. Herder stated that the volk is the only class, and includes both King and peasant, and that “the people” are not the same as the rabble that are championed by Jacobinism and later Marxism.

French and English racism was introduced to Germany by the Englishman Houston Stewart Chamberlain who had a seminal influence on Hitlerism. English Darwinism, a manifestation of the materialistic Zeitgeist that dominated England, was brought to Germany by Ernst Haeckel; although Blumenbach had already begun to classify race according to cranial measurements during the 18th century. Nonetheless, biological racism reflects the English Zeitgeist of materialism. It provided primary materialistic doctrines to dethrone Tradition. Its application to economics also provided a scientific justification for the “class struggle” of both the capitalistic and socialistic varieties. Hitlerism was an attempt to synthesis the English eugenics of Galton and the evolution of Darwin with the metaphysis of German Idealism. Italian Traditionalist Julius Evola attempted to counter the later influence of Hitlerian racism on Italian Fascism by developing a “metaphysical racism,” and the concept of the “race of the spirit,” which has its parallels in Spengler, whose approach to race is in the Traditionalist mode of the German Idealists.

French and English racism was introduced to Germany by the Englishman Houston Stewart Chamberlain who had a seminal influence on Hitlerism. English Darwinism, a manifestation of the materialistic Zeitgeist that dominated England, was brought to Germany by Ernst Haeckel; although Blumenbach had already begun to classify race according to cranial measurements during the 18th century. Nonetheless, biological racism reflects the English Zeitgeist of materialism. It provided primary materialistic doctrines to dethrone Tradition. Its application to economics also provided a scientific justification for the “class struggle” of both the capitalistic and socialistic varieties. Hitlerism was an attempt to synthesis the English eugenics of Galton and the evolution of Darwin with the metaphysis of German Idealism. Italian Traditionalist Julius Evola attempted to counter the later influence of Hitlerian racism on Italian Fascism by developing a “metaphysical racism,” and the concept of the “race of the spirit,” which has its parallels in Spengler, whose approach to race is in the Traditionalist mode of the German Idealists.

Because the Right, the custodian of Tradition within the epoch of decay, has been infected by the spirit of materialism, there is often a focus on secondary symptoms of culture disease, such as in particular immigration, rather than primary symptoms such as usury and plutocracy. “Race” becomes a matter of skull measuring, rather than spirit, élan and character. Hence the character of a civilisation and of a people is discerned via the types of bone and skull found amidst the ruins. History then becomes a matter of counting and measuring and statistics. How feeble such attempts remain is demonstrated by the years of controversy surrounding the racial identity of Kennewick Man in North America, having first thought to have been a Caucasian, and now concluded to have been of Ainu/Polynesian descent. The Traditionalist does not discount “race”. Rather it plays a central role. How “race” is defined is another matter.

Trotsky called “racism” “Zoological materialism”. As an “economic materialist”, that is, a Marxist, he did not explain why his own version of materialism is a superior mode of thinking and acting than the other. They arose, along with Free Trade capitalism, out of the same Zeitgeist that dominated England at the time, and all three refer to a naturalistic life as struggle. The Traditionalist rejects all forms of materialism. The Traditionalist does not see history as unfolding according to material, economic forces, or racial-biological determinants. The Traditionalist sees history as the unfolding of metaphysical forces manifesting within the terrestrial. Spengler, although not a Perennial Traditionalist, intuited history over a broad expanse as a metaphysical unfolding. Although a man of the “Right”, he rejected the biological interpretation of history as much as the economic. So did Evola.

The best known exponents of racial determinism were of course German National Socialists, the reductionist doctrine being expressed by Hitler:

“…This is how civilisations and empires break up and make room for new creations. Blood mixture, and the lowering of the racial level which accompanies it, are the one and only cause why old civilisations disappear…”

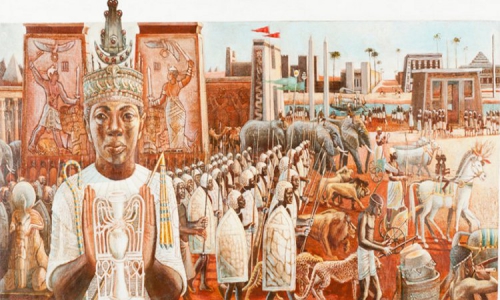

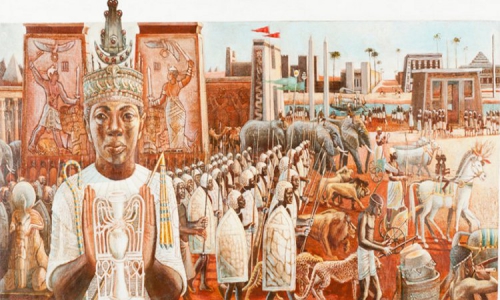

The USA provided a large share of racial theorists of the early 20th century, whose conception of the rise and fall of civilisation was based on racial zoology, and in particular on the superiority of the Nordic not only above non-white races, but above all sub-races of the white, such as the Dinaric, Mediterranean and Alpine. Senator Theodore G. Bilbo of Mississippi wrote a book championing the cause of segregation, and more so, the “back-to-Africa” movement, stating that miscegenation with the Negro will result in the fall of white civilisation. He briefly examined some major civilisations. Bilbo wrote that Egyptian civilisation was mongrelised over centuries, “until a mulatto inherited the throne of the Pharaohs in the Twenty-fifth dynasty. This mongrel prince, Taharka, ruled over a Negroid people whose religion had fallen from an ethical test for the life after death to a form of animal worship”. This should be “sufficient warning to white America!” Because Sen. Bilbo had started from an assumption, his history was flawed. As will be shown below, it was Taharka and the Nubian dynasty that renewed Egypt’s decaying culture, which had degenerated under the white Libyan dynasties. Sen. Bilbo proceeds with similar brief examinations of Carthage, Greece, and Rome.

Julius Evola, while repudiating the zoological primacy of “racism” as another form of materialism and therefore anti-Traditional, suggested that a “spiritual racism” is necessary to oppose the forces seeking to turn man into an amorphous mass; as interchangeable economic units without roots; what is now called “globalisation”.

Julius Evola, while repudiating the zoological primacy of “racism” as another form of materialism and therefore anti-Traditional, suggested that a “spiritual racism” is necessary to oppose the forces seeking to turn man into an amorphous mass; as interchangeable economic units without roots; what is now called “globalisation”.

Evola gives the Traditionalist viewpoint when stating that there “have been many cases in which a culture has collapsed even when its race has remained pure, as is especially clear in certain groups that have suffered slow, inexorable extinction despite remaining as racially isolated as if they were islands”. He gives Sweden and The Netherlands as recent examples, pointing out that although the race has remained unchanged, there is little of the “heroic disposition” those cultures possessed just several centuries previously. He refers to other great cultures as having remained in a state as if like mummies, inwardly dead, awaiting a push “to knock them down”. These are what Spengler called Fellaheen, spiritually exhausted and historically passé. Evola gives Peru as an example of how readily a static culture succumbed to Spain. Hence, such examples, even as vigorous cultures such as that of the Dutch and Scandinavian, once wide-roaming and dynamic, have declined to nonentities despite the maintenance of racial homogeneity.

The following considers examples that are often cited as civilisations that decayed and died as the result of miscegenation.

Greek

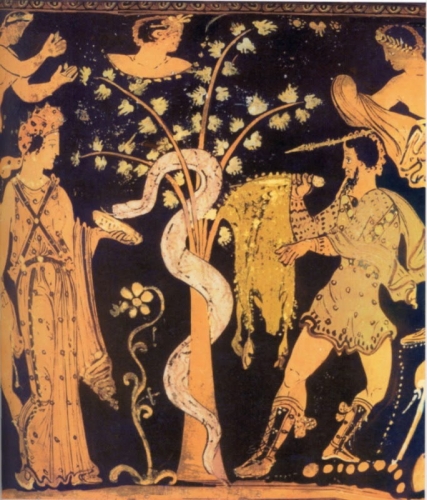

A case study for testing the miscegenation theory of cultural decay is that of the Hellenic. The ancient Hellenic civilisation is typically ascribed by racial theorists as being the creation of a Nordic culture-bearing stratum. The same has been said of the Latin, Egyptian, and others. Typically, this theory is illustrated by depicting sculptures of ancient Hellenes of “Nordic” appearance. Such depictions upon which to form a theory are unreliable: the ancient Hellenes were predominantly a mixture of Dinaric-Alpine-Mediterranean. The skeletal remains of Greeks show that from earliest times to the present there has been remarkable uniformity, according to studies by Sergi, Ripley, and Buxton, who regarded the Greeks as an Alpine-Mediterranean mix from a “comparatively early date.” American physical anthropologist Carlton S. Coon stated that the Greeks remain an Alpine/Mediterranean mix, with a weak Nordic element, being “remarkably similar” to their ancient ancestors.

American anthropologist J. Lawrence Angel, in the most complete study of Greek skeletal remains starting from the Neolithic era to the present, found that Greeks have always bene marked by a sustained racial continuity. Angel cited American anthropologist Buxton who had studied Greek skeletal material and measured modern Greeks, especially in Cyprus, concluding that the modern Greeks “possess physical characteristics not differing essentially from those of the former [ancient Greeks]”. The most extensive study of modern Greeks was conducted by anthropologist Aris N. Poulianos, concluding that Greeks are and have always been Mediterranean-Dinaric, with a strong Alpine presence. Angel states that “Poulianos is correct in pointing out ... that there is complete continuity genetically from ancient to modern times”. Nikolaos Xirotiris did not find any significant alteration of the Greek race from prehistory, through classical and medieval, to modern times. Anthropologist Roland Dixon studied the funeral masks of Spartans and identified them as of the Alpine sub-race. Although race theorists often stated that Hellenic civilisation was founded and maintained by invading Dorian “Nordics”, Angel states that the northern invasions were always of “Dinaroid-Alpine” type. A recent statistical comparison of ancient and modern Greek skulls found “a remarkable similarity in craniofacial morphology between modern and ancient Greeks.”

If miscegenation and the elimination of an assumed Nordic (Dorian) culture-bearing stratum cannot account for the decay of Hellenic civilisation, what can? Contemporary historians point out the origins. The Roman historian Livy observed:

“The Macedonians who settled in Alexandria in Egypt, or in Seleucia, or in Babylonia, or in any of their other colonies scattered over the world, have degenerated into Syrians, Parthians, or Egyptians. Whatever is planted in a foreign land, by a gradual change in its nature, degenerates into that by which it is nurtured”.

Here Livy is observing that occupiers among foreign peoples “go native”, as one might say. The occupiers are pulled downward, rather than elevating their subjects upward, not through genetic contact but through moral and cultural corruption. The Syrians, Parthians and Egyptians, had already become historically and culturally passé, or Fellaheen, as Spengler puts it. The Macedonian Greeks in those colonies succumbed to the force of etiolation. Alexander even encouraged this in an effort to meld all subjects into one Greek mass, which resulted not from a Hellenic civilisation passed along by multitudinous peoples, but in a chaotic mass from which Greece did not recover, despite the Greeks staying racially intact. Unlike the Jews in particular, the Greeks, Romans and other conquerors did not have the strength of Tradition to maintain themselves among alien cultures. Dr. W. W. Tarn stated of this process:

Here Livy is observing that occupiers among foreign peoples “go native”, as one might say. The occupiers are pulled downward, rather than elevating their subjects upward, not through genetic contact but through moral and cultural corruption. The Syrians, Parthians and Egyptians, had already become historically and culturally passé, or Fellaheen, as Spengler puts it. The Macedonian Greeks in those colonies succumbed to the force of etiolation. Alexander even encouraged this in an effort to meld all subjects into one Greek mass, which resulted not from a Hellenic civilisation passed along by multitudinous peoples, but in a chaotic mass from which Greece did not recover, despite the Greeks staying racially intact. Unlike the Jews in particular, the Greeks, Romans and other conquerors did not have the strength of Tradition to maintain themselves among alien cultures. Dr. W. W. Tarn stated of this process:

“Greece was ready to adopt the gods of the foreigner, but the foreigner rarely reciprocated; Greek Doura (the Greek temple in Mesopotamia) freely admitted the gods of Babylon, but no Greek god entered Babylonian Uruk. Foreign gods might take Greek names; they took little else. They (the Babylonian gods) were the stronger, and the conquest of Asia (by the Greeks) was bound to fail as soon as the East had gauged its own strength and Greek weakness.”

Spengler pointed out to Western Civilisation and the current epoch that one of the primary symptoms of culture decay is that of depopulation. It is a sign literally that a Civilisation has become too lazy to look beyond the immediate. There is no longer any sense of duty to the past or the future, but only to a hedonistic present. Polybius (b. ca. 200 B.C.) observed this phenomenon of Hellenic Civilisation like Spengler did of ours, writing:

“In our time all Greece was visited by a dearth of children and generally a decay of population, owing to which the cities were denuded of inhabitants, and a failure of productiveness resulted, though there were no long-continued wars or serious pestilences among us. If, then, any one had advised our sending to ask the gods in regard to this, what we were to do or say in order to become more numerous and better fill our cities,—would he not have seemed a futile person, when the cause was manifest and the cure in our own hands? For this evil grew upon us rapidly, and without attracting attention, by our men becoming perverted to a passion for show and money and the pleasures of an idle life, and accordingly either not marrying at all, or, if they did marry, refusing to rear the children that were born, or at most one or two out of a great number, for the sake of leaving them well off or bringing them up in extravagant luxury. For when there are only one or two sons, it is evident that, if war or pestilence carries off one, the houses must be left heirless: and, like swarms of bees, little by little the cities become sparsely inhabited and weak. On this subject there is no need to ask the gods how we are to be relieved from such a curse: for any one in the world will tell you that it is by the men themselves if possible changing their objects of ambition; or, if that cannot be done, by passing laws for the preservation of infants”.

“In our time all Greece was visited by a dearth of children and generally a decay of population, owing to which the cities were denuded of inhabitants, and a failure of productiveness resulted, though there were no long-continued wars or serious pestilences among us. If, then, any one had advised our sending to ask the gods in regard to this, what we were to do or say in order to become more numerous and better fill our cities,—would he not have seemed a futile person, when the cause was manifest and the cure in our own hands? For this evil grew upon us rapidly, and without attracting attention, by our men becoming perverted to a passion for show and money and the pleasures of an idle life, and accordingly either not marrying at all, or, if they did marry, refusing to rear the children that were born, or at most one or two out of a great number, for the sake of leaving them well off or bringing them up in extravagant luxury. For when there are only one or two sons, it is evident that, if war or pestilence carries off one, the houses must be left heirless: and, like swarms of bees, little by little the cities become sparsely inhabited and weak. On this subject there is no need to ask the gods how we are to be relieved from such a curse: for any one in the world will tell you that it is by the men themselves if possible changing their objects of ambition; or, if that cannot be done, by passing laws for the preservation of infants”.

Do Polybius’ thoughts sound like some unheeded doom-sayer speaking to us now about our modern world? If the reader can see the analogous features between Western Civilisation, and that of Greece and Rome then the organic course of Civilisations is being understood, and by looking at Greece and Rome we might see where we are heading.

Roman

Another often cited example of the fall of civilisation through miscegenation is that of Rome. However, despite the presence of slaves and traders of sundry races, like the Greeks, today’s Italians are substantially the same as they were in Roman times. Arab influence did not occur until Medieval times, centuries after the “fall of Rome”, with Arab rule extending over Sicily only during 1212-1226 A.D. The genetic male influence on Sicilians is estimated at only 6%. The predominant genetic influence is ancient Greek. The African have a less than 1% frequency throughout Italy other than in , , and where there are frequencies of 2% to 3% . Sub-Saharan, that is, Negroid, mtDNA have been found at very low frequencies in Italy, albeit marginally higher than elsewhere in Europe, but date from 10,000 years ago. This study states: “….mitochondrial DNA studies show that Italy does not differ too much from other European populations”. Although there are small regional variations, “The mtDNA haplogroup make-up of Italy as observed in our samples fits well with expectations in a typical European population”.

Hence, an infusion of Negroid or Asian genes during the epoch of Rome’s decline and fall is lacking, and the reasons for that fall cannot be assigned to miscegenation. What slight frequency there is of non-Caucasian genetic markers entered Rome long before or long after the fall of Roman Civilisation. There was no “contamination of Roman blood”, but of Roman spirit and élan.

Alien immigration introduces cultural elements that dislocate the social and ethical basis of a Civilisation and aggravate an existing pathological condition. The English scholar Professor C. Northcote Parkinson, writing on the fall of Rome, commented that the Roman conquerors were subjected “to cultural inundation and grassroots influence”. Because Rome extended throughout the world, like the present Late Western, the economic opportunities accorded by Rome drew in all the elements of the subject peoples, “groups of mixed origin and alien ways of life”. “Even more significant was what the Romans learnt while on duty overseas, for men so influenced were of the highest rank”. Parkinson quotes Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, referring to the Roman colony of Antioch:

Alien immigration introduces cultural elements that dislocate the social and ethical basis of a Civilisation and aggravate an existing pathological condition. The English scholar Professor C. Northcote Parkinson, writing on the fall of Rome, commented that the Roman conquerors were subjected “to cultural inundation and grassroots influence”. Because Rome extended throughout the world, like the present Late Western, the economic opportunities accorded by Rome drew in all the elements of the subject peoples, “groups of mixed origin and alien ways of life”. “Even more significant was what the Romans learnt while on duty overseas, for men so influenced were of the highest rank”. Parkinson quotes Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, referring to the Roman colony of Antioch:

“…Fashion was the only law, pleasure the only pursuit, and the splendour of dress and furniture was the only distinction of the citizens of Antioch. The arts of luxury were honoured, the serious and manly virtues were the subject of ridicule, and the contempt for female modesty and reverent age announced the universal corruption of the capitals of the East…”

Roman historian Livy wrote of the opulence of Asia being brought back to Rome by the soldiery:

“…it was through the army serving in Asia that the beginnings of foreign luxury were introduced into the City. These men brought into Rome for the first time, bronze couches, costly coverlets, tapestry, and other fabrics, and - what was at that time considered gorgeous furniture - pedestal tables and silver salvers. Banquets were made more attractive by the presence of girls who played on the harp and sang and danced, and by other forms of amusement, and the banquets themselves began to be prepared with greater care and expense. The cook whom the ancients regarded and treated as the lowest menial was rising in value, and what had been a servile office came to be looked upon as a fine art. Still what met the eye in those days was hardly the germ of the luxury that was coming”.

The moral decay of Rome resulted in the displacement of Roman stock, not by miscegenation, but by the falling birth-rate of the Romans. Such population decline is itself a major symptom of culture decay. The problem that it signifies is that a people has so little consciousness left as to its own purpose as a culture that its individuals do not have any responsibility beyond their own egos. Professor Tenney Frank, foremost scholar on the economic history of Rome, also considered the results of population decline, from the top of the social hierarchy downward:

“The race went under. The legislation of Augustus and his successors, while aiming at preserving the native stock, was of the myopic kind so usual in social lawmaking, and failing to reckon with the real nature of the problem involved. It utterly missed the mark. By combining epigraphical and literary references, a fairly full history of the noble families can be procured, and this reveals a startling inability of such families to perpetuate themselves. We know, for instance, in Caesar’s day of forty-five patricians, only one of whom is represented by posterity when Hadrian came to power. The Aemilsi, Fabii, Claudii. Manlii, Valerii, and all the rest, with the exception of Comelii, have disappeared. Augustus and Claudius raised twenty-five families to the patricate, and all but six disappear before Nerva’s reign. Of the families of nearly four hundred senators recorded in 65 A. D. under Nero, all trace of a half is lost by Nerva’s day, a generation later. And the records are so full that these statistics may be assumed to represent with a fair degree of accuracy the disappearance of the male stock of the families in question. Of course members of the aristocracy were the chief sufferers from the tyranny of the first century, but this havoc was not all wrought by delatores and assassins. The voluntary choice of childlessness accounts largely for the unparalleled condition. This is as far as the records help in this problem, which, despite the silences is probably the most important phase of the whole question of the change of race. Be the causes what they may, the rapid decrease of the old aristocracy and the native stock was clearly concomitant with a twofold increase from below; by a more normal birth-rate of the poor, and the constant manumission of slaves

While allusions to “race” by Professor Frank are enough for “zoological materialists” to spin a whole theory about Rome’s decline and fall around miscegenation of the “white race” with blacks and Orientals, we now know from the genetics that despite the invasions over centuries, the Italians, like the Greeks, have retained their original racial composition to the present. What Frank is describing, by an examination of the records that show a disappearance of the leading patrician families, is that Rome was in a spiritual crisis, as all civilisations are when they regard child-bearing as a burden. Traditionalists such as Evola pointed out that the “secret of degeneration” of a civilisation is that it rots from the top downward, and as Spengler pointed out, one of the primary signs of that rot is childlessness. That there were Roman statesmen with the wisdom to understand what was happening is indicated by Augustus’ efforts to raise the birth-rate, but to no avail. Of this symptom of moral decay, Professor Frank wrote:

“In the first place there was a marked decline in the birthrate among the aristocratic families. … As society grew more pleasure-loving, as convention raised artificially the standard of living, the voluntary choice of celibacy and childlessness became a common feature among the upper classes. …”

Urbanisation, the magnetic pull of the megalopolis, the depopulation of the land and the proletarianism of the former peasant stock as in the case of the West’s Industrial Revolution, impacted in major ways on the fall of Rome. A. M. Duff wrote of the impact of rural depopulation and urbanisation:

“But what of the lower-class Romans of the old stock? They were practically untouched by revolution and tyranny, and the growth of luxury cannot have affected them to the same extent as it did the nobility. Yet even here the native stock declined. The decay of agriculture. … drove numbers of farmers into the towns, where, unwilling to engage in trade, they sank into unemployment and poverty, and where, in their endeavours to maintain a high standard of living, they were not able to support the cost of rearing children. Many of these free-born Latins were so poor that they often complained that the foreign slaves were much better off than they, and so they were. At the same time many were tempted to emigrate to the colonies across the sea which Julius Caesar and Augustus founded. Many went away to Romanize the provinces, while society was becoming Orientalized at home. Because slave labour had taken over almost all jobs, the free born could not compete with them. They had to sell their small farms or businesses and move to the cities. Here they were placed on the doles because of unemployment. They were, at first, encouraged to emigrate to the more prosperous areas of the empire to Gaul, North Africa and Spain. Hundreds of thousands left Italy and settled in the newly-acquired lands. Such a vast number left Italy leaving it to the Orientals that finally restrictions had to be passed to prevent the complete depopulation of the Latin stock, but as we have seen, the laws were never effectively put into force. The migrations increased and Italy was being left to another race. The free-born Italian, anxious for land to till and live upon, displayed the keenest colonization activity.”

The foreign cultures and religions that had come to Rome from across the empire changed the temperament of the Romans masses who were uprooted and migrating to the cities; where as in the nature of the cites, as Spengler showed, they became a cosmopolitan mass. Frank writes of this:

“This Orientalization of Rome’s populace has a more important bearing than is usually accorded it upon the larger question of why the spirit and acts of imperial Rome are totally different from those of the republic. There was a complete change in the temperament! There is today a healthy activity in the study of the economic factors that contributed to Rome’s decline. But what lay behind and constantly reacted upon all such causes of Rome’s disintegration was, after all, to a considerable extent, the fact that the people who had built Rome had given way to a different race. The lack of energy and enterprise, the failure of foresight and common sense, the weakening of moral and political stamina, all were concomitant with the gradual diminution of the stock which, during the earlier days, had displayed these qualities. It would be wholly unfair to pass judgment upon the native qualities of the Orientals without a further study, or to accept the self-complacent slurs of the Romans, who, ignoring certain imaginative and artistic qualities, chose only to see in them unprincipled and servile egoists. We may even admit that had these new races had time to amalgamate and attain a political consciousness a more brilliant and versatile civilization might have come to birth.”

What is notable is not that the Romans miscegenated with Orientals, but that the uprooted, amorphous masses of the cities no longer adhered to the Traditions on which Roman civilisation was founded. The same process can be seen today at work in New York, London and Paris. Duff wrote of this, and we might consider the parallels with our own time:

What is notable is not that the Romans miscegenated with Orientals, but that the uprooted, amorphous masses of the cities no longer adhered to the Traditions on which Roman civilisation was founded. The same process can be seen today at work in New York, London and Paris. Duff wrote of this, and we might consider the parallels with our own time:

“Instead of the hardy and patriotic Roman with his proud indifference to pecuniary gain, we find too often under the Empire an idle pleasure-loving cosmopolitan whose patriotism goes no further than applying for the dole and swelling the crowds in the amphitheatre”.

The Roman Traditional ethos of severity, austerity and disdain for softness that Emperor Julian attempted to reassert was greeted by “fashionable society” with “disgust”. Parkinson remarks that “there is just such a tendency in the London of today, as there was still earlier in Boston and New York”. These “world cities” no longer reflect a cultural nexus but an economic nexus, and hence one’s position is not based on how one or one’s family unfolds the Traditional ethos, but on whether or how one accumulates wealth.

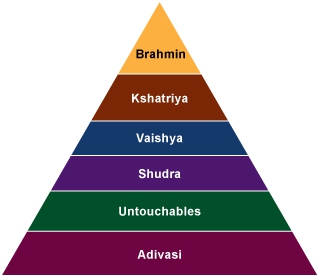

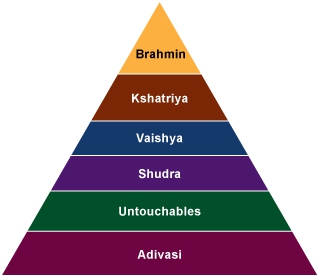

Indian

India is the most commonly cited example of a civilisation that decayed through miscegenation, the invading Aryans imparting a High Culture on India and then forever falling into decay because of miscegenation with the low caste “blacks”, or Dravidians. However, Genetic research indicates that the higher castes have retained to the present a predominately Caucasian genetic inheritance.

India is the most commonly cited example of a civilisation that decayed through miscegenation, the invading Aryans imparting a High Culture on India and then forever falling into decay because of miscegenation with the low caste “blacks”, or Dravidians. However, Genetic research indicates that the higher castes have retained to the present a predominately Caucasian genetic inheritance.

“As one moves from lower to upper castes, the distance from Asians becomes progressively larger. The distance between Europeans and lower castes is larger than the distance between Europeans and upper castes, but the distance between Europeans and middle castes is smaller than the upper caste-European distance. … Among the upper castes the genetic distance between Brahmins and Europeans (0.10) is smaller than that between either the Kshatriya and Europeans (0.12) or the Vysya and Europeans (0.16). Assuming that contemporary Europeans reflect West Eurasian affinities, these data indicate that the amount of West Eurasian admixture with Indian populations may have been proportionate to caste rank.

“…As expected if the lower castes are more similar to Asians than to Europeans, and the upper castes are more similar to Europeans than to Asians, the frequencies of M and M3 haplotypes are inversely proportional to caste rank.

“…In contrast to the mtDNA distances, the Y-chromosome STR data do not demonstrate a closer affinity to Asians for each caste group. Upper castes are more similar to Europeans than to Asians, middle castes are equidistant from the two groups, and lower castes are most similar to Asians. The genetic distance between caste populations and Africans is progressively larger moving from lower to middle to upper caste groups.

“…Results suggest that Indian Y chromosomes, particularly upper caste Y chromosomes, are more similar to European than to Asian Y chromosomes.

“…Nevertheless, each separate upper caste is more similar to Europeans than to Asians.”

Citing further studies, “…admixture with African or proto-Australoid populations” is “occasional”.

The chaos that afflicted India seems to have been of religio-cultural type rather than racial. Despite the superficiality of dusky hues, the Indian ruling castes have retained their Caucasian identity to the present. The genetic contribution of Australoids and Africans was minor.

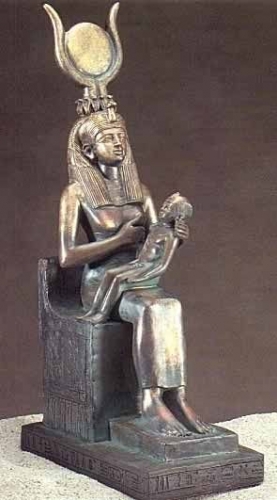

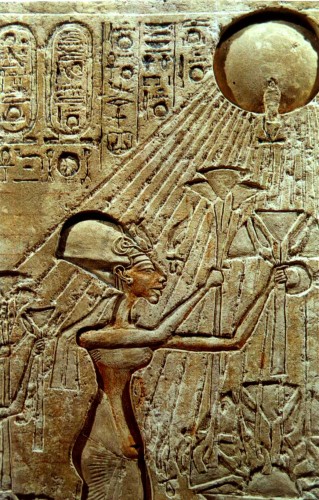

Egyptian

Like India, Egypt is often cited as an example of a civilisation that was destroyed primarily by miscegenation, with Negroids. However, despite the myriad of invasions and population shifts, today’s Egyptians are still more closely related genetically to Eurasia than Africa. Migrations between Egypt, Nubia and Sudan have not been extensive enough to “homogenise the mtDNA gene pools of the Nile River Valley populations”, although Egyptians and Nubians are more closely related than Egyptians and southern Sudanese. However, significant differences remain. Even now, today’s Egyptians have primary genetic affinities with Asia, and North and Northeast Africa. The least affinity is to the populations of Sub-Sahara. The Haplotype M1, with a high frequency among Egyptians, hitherto thought to be of Sub-Saharan origin, is of Eurasian origin.

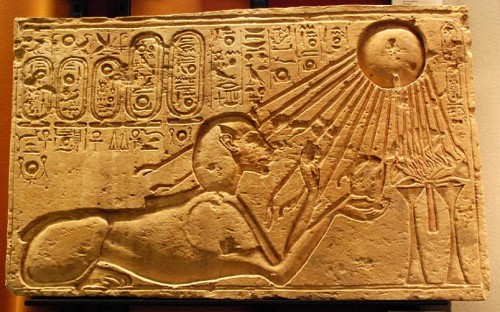

Miscegenation with Nubian “slaves” and mercenaries seems unlikely to have caused Egypt’s decay. While a Nubian or “black” pharaoh is alluded to by racial-zoologists as a sign of Egyptian decay, the Nubian civilisation had an intimate connection with the Egyptian and was itself impressive and of early origins.

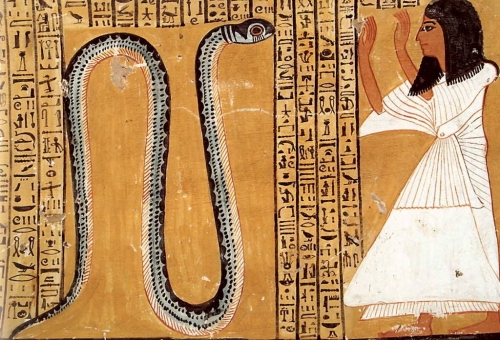

Nubian civilisation, with palaces, temples and pyramids, flourished as far back as 7000 B.C. 223 pyramids, twice the number of Egypt, have been found along the Nile of the Nubian culture-region. The Nubian civilisation was of notably long duration surviving until the Muslim conquest of 1500 A.D. The Egyptians have viewed the Nubians either as a “conquered race or a superior enemy”. Hence, Egyptian depictions of shackled black slaves, give a widely inaccurate impression of the Nubian. Nubians became the pharaohs of Egypt’s 25th dynasty, providing stability where previously there had been ruin caused by civil wars between warlords, ca. 700 B.C. The Nubians were the custodians of Egyptian faith and culture at a time when Egypt was decaying. They regarded the restoration of the faith of Amun as their duty. It was the Nubian dynasties (760-656 B.C.), especially the rulership of Taharqa, which revived and purified Egyptian culture and religion. It was under the “white” rule of the Libyan pharaohs of the 21st dynasty (1069-1043 B. c.) that Egypt began a sharp decline. Ptolemaic (Greek) rule (332-30 B.C.) under Ptolemy IV (222 to 205 B.C.) brought to the rich and sumptuous pharaohs’ court “lax morals and vicious lifestyle” ending in “decadence and anarchy”. Byzantine rule (395 to 640 A.D.) through Christianisation wrought destruction on the Egyptian heritage, which was succeeded by Islamic rule. Of the long vicissitudes of Egypt’s rise and fall, it was the Nubian dynasty that had restored Egyptian cultural integrity. References to Nubians on the throne of the pharaohs tell no more of the causes of Egypt’s decay than if historians several millennia hence sought to ascribe the causes of the USA’s culture retardation to Obama’s presidency as a “black”.

We see in Egypt as in Rome, the Moorish civilisation, India and others, the causes of culture decay and fall as being something other than miscegenation. The contemporary Westerner should look for answers beyond this if only because he can see for himself that the West’s decay has no relationship to miscegenation. The number of Americans describing themselves as “mixed race” was just under 9 million in 2010. Of the 3,988,076 live births in the USA in 2014 368,213 were non-white. The USA did not become the global centre of culture-pestilence because of its mixed race population. What is more significant than the percentages of miscegenation, are the percentages of population decline caused by such factors as the limitation of children, and the rates of abortion. Twenty-one percent of all pregnancies in the USA are aborted. Such depopulation statics are an indication of culture pathology.

Of Egypt’s chaos contemporary sages observed, as they did of Rome and India, a disintegration of authority, traditional religion, and the founding ethos and mythos around which a healthy culture revolves. Egypt was often subjected to invasions and to natural disasters. These served as catalysts for culture degeneration. The papyrus called The Admonitions of an Egyptian Sage, state that after invasions and what seems to have been a class war, Egypt fell apart, there was family strife, the noble families were dispossessed by the lowest castes, authority was disrespected and overthrown, lawlessness and plunder were the norm, and the nobility was attacked: “A man looks upon his son as an enemy. A man smites his brother (the son of his mother)”. Craftsmanship has become degraded: “No craftsmen work, the enemies of the land have spoilt its crafts”. There is rebellion against the Uraeus or Re. “A few lawless men have ventured to despoil the land of the kingship”. It appears that the foundations of Traditional society, god, monarch, family and land, have been caste asunder. Further, “Asiatics” have seized the land from the ancestral occupiers, and have so insinuated themselves into the Egyptian culture that one can no longer tell who is Egyptian and who is alien: “There are no Egyptians anywhere”. “Women are lacking and no children are conceived”. Evidently there is a population crisis; that perennial symptom of decay. The political and administrative structure has collapsed, with “no officers in their place”. The laws are trampled on and cast aside. “Serfs become lords of serfs”. The writings of the scribes are destroyed.

Of Egypt’s chaos contemporary sages observed, as they did of Rome and India, a disintegration of authority, traditional religion, and the founding ethos and mythos around which a healthy culture revolves. Egypt was often subjected to invasions and to natural disasters. These served as catalysts for culture degeneration. The papyrus called The Admonitions of an Egyptian Sage, state that after invasions and what seems to have been a class war, Egypt fell apart, there was family strife, the noble families were dispossessed by the lowest castes, authority was disrespected and overthrown, lawlessness and plunder were the norm, and the nobility was attacked: “A man looks upon his son as an enemy. A man smites his brother (the son of his mother)”. Craftsmanship has become degraded: “No craftsmen work, the enemies of the land have spoilt its crafts”. There is rebellion against the Uraeus or Re. “A few lawless men have ventured to despoil the land of the kingship”. It appears that the foundations of Traditional society, god, monarch, family and land, have been caste asunder. Further, “Asiatics” have seized the land from the ancestral occupiers, and have so insinuated themselves into the Egyptian culture that one can no longer tell who is Egyptian and who is alien: “There are no Egyptians anywhere”. “Women are lacking and no children are conceived”. Evidently there is a population crisis; that perennial symptom of decay. The political and administrative structure has collapsed, with “no officers in their place”. The laws are trampled on and cast aside. “Serfs become lords of serfs”. The writings of the scribes are destroyed.

What is being described is not a sudden upheaval, although the allusion to natural disasters and Asiatic invasion would imply this. The breakdown of regal authority, civil authority, depopulation, laws, family bonds, religious faith, agriculture and the social structure, imply an epoch of decline into chaos. The social structure has been inversed, as though a communistic revolution had occurred. “He who possessed no property is now a man of wealth. The prince praises him. The poor of the land have become rich, and the possessor of the land has become one who has nothing. Female slaves speak as they like to their mistresses. Orders become irksome. Those who could not build a boat now possesses ships. “The possessors of robes are now in rags”. “The children of princes are cast out in the street”.

With this inversion of hierarchy has come irreligion and the degradation of religion. The ignorant now perform their own rites to the Gods. Wrong offerings are made to the Gods. “Right is cast aside. Wrong is inside the council-chamber. The plans of the gods are violated, their ordinances are neglected… Reverence, an end is put to it”.

Ipuwer’s admonition was not only to rid Egypt of its enemies but to return to the Traditional ethos. This meant the reinstitution of proper religious rites, and the purification of the temples. “A fighter comes forth,” Ipuwer prophesises, to “destroy the wrongs”. “Is he sleeping? Behold, his might is not seen”. The Egyptians await an avatar, the personification of the Sun God Re (which Tradition states was the first of the Pharaohs) an Arthur who sleeps but will awaken, a redeemer that is a universal symbol from the Hindu Kalki, to Jesus in the vision of John of Patmos, the Katehon of Orthodox Russia, and many others across time and place.

Ipuwer avers to Egypt having gone through such epochs, alluding to his saying nothing other than what others have said before his time.

Ipuwer avers to Egypt having gone through such epochs, alluding to his saying nothing other than what others have said before his time.

The Pharaoh is castigated for allowing Egypt to fall into chaos, with his authority being undermined, and without taking corrective actions. The Pharaoh as God-king, in terms of Tradition, had not maintained his authority as the nexus between the earthly kingdom and the Divine. The Pharaoh had caused “confusion throughout the land”. Certainty of the social hierarchy, crowned by the God-king, is the basis of Traditional societies. It seems that Egypt had entered into an epoch of what a Westerner could today identify in our time as that of scepticism and secularism. Chaos follows with the undermining of Cosmos.

Nefer-rohu warned Pharaoh of similar chaos. Likewise there would be “Asiatic” invasions, natural disasters, Re withdrawing his light, and again the inversion of hierarchy:

“The weak of arm is now the possessor of an arm. Men salute respectfully him whom formerly saluted. I show thee the undermost on top, turned about in proportion to the turning about of my belly. It is the paupers who eat the offering bread, while the servants jubilate. The Heliopolitan Nome, the birthplace of every god, will no longer be on earth”.

It is notable, again, that Nefer-rohu identifies the chaos with the breaking of the nexus with the divine, and the social order that has become “the undermost on top”. Also of interest is that Nefer-rohu refers to a redeemer, who has a Nubian mother, uniting Egypt and driving out the Asiatics, and the Libyans (the whitest of races of the region) and defeating the rebellious. Chaos resulted not from bio-genetic-race-factors but from a falling away of the regal and religious authority. If there is a race-factor it is in regard to Nubians being the custodians of Egyptian culture in periods of Egyptian decay, analogous to the revitalising “barbarians” who wept over the decaying Roman Empire.

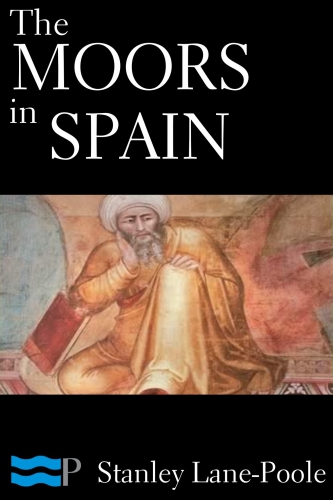

Islamic

Islam had its Golden Age and rich civilisation, centred in Morocco, and extending into Spain. It is in ruins like civilisations centuries prior. The cultures that flourished in Morocco, both Islamic and pre-Islamic, were Berber. The Islamic civilisation they established with the founding of the Idrisid dynasty in 788 A. D. was ended by the invasion of the Fatimids from Tunisia ca. 900 A.D. Chaos ensued. Although there was a revival of High Culture during the 11th and 14th centuries, dynasties fell in the face of tribalism. The 16th century saw a revival initiated by al-Ghalin, several decades of wars of succession after his death in 1603, and continuing decline under Saadi dynastic rule during 1627 to 1659.

Caucasoid mtDNA sequences are at frequencies of 96% in Moroccan Berbers, 82% in Algerian Berbers and 78% in non-Berber Moroccans. The study of Esteban et al found that Moroccan Northern and Southern Berbers have only 3% to 1% Sub-Saharan mtDNA. Although difficult to define, since “Berber” is a Roman, not an indigenous term, the estimate for present day Morocco is 35% to 45% Berber, with the rest being Berber-Arab mixture. The primary point is that the Moroccan civilisation had ruling classes, whether pre-Islamic or Islamic, that remained predominantly Berber-Caucasian for most of its history, whether during its epochs of glory or of decline. Miscegenation does not account for the fall of the Moorish Civilisation.

Caucasoid mtDNA sequences are at frequencies of 96% in Moroccan Berbers, 82% in Algerian Berbers and 78% in non-Berber Moroccans. The study of Esteban et al found that Moroccan Northern and Southern Berbers have only 3% to 1% Sub-Saharan mtDNA. Although difficult to define, since “Berber” is a Roman, not an indigenous term, the estimate for present day Morocco is 35% to 45% Berber, with the rest being Berber-Arab mixture. The primary point is that the Moroccan civilisation had ruling classes, whether pre-Islamic or Islamic, that remained predominantly Berber-Caucasian for most of its history, whether during its epochs of glory or of decline. Miscegenation does not account for the fall of the Moorish Civilisation.

The High Culture of Moorish Spain (Andalusia) was brought to ruin and decay not by miscegenation between “superior” Spaniards” and “inferior” Moors but by the overthrow of the Moorish ruling caste. Friedrich Nietzsche had observed this culture denegation with the fall of Moorish Spain (Andalusia). Stanley Lane-Poole wrote of the history of decay:

“The land, deprived of the skilful irrigation of the Moors, grew impoverished and neglected; the richest and most fertile valleys languished and were deserted; most of the populous cities which had filled every district of Andalusia fell into ruinous decay; and beggars, friars, and bandits took the place of scholars, merchants, and knights. So low fell Spain when she had driven away the Moors. Such is the melancholy contrast offered by her history”.

Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406), a well-travelled sage, grappled with the same problems confronting Islamic Civilisation as those Spengler confronted in regard to The West. A celebrated scholar, political adviser, and jurist, Ibn Khaldun’s domain of influence extended over the whole Islamic world. His major theoretical work is Muqaddimah (1377), intended as a preface to his universal history, Kitabal-Ibar, where he sought to establish basic principles of history by which historians could understand events. His theory is cyclic and morphological, based on “conditions within nations and races [which] change with the change of periods and the passage of time”. Like Evolahe was pessimistic as to what can be achieved by political action in the cycle of decline, writing that the “past resembles the future more than one drop of water another”.

Ibn Khaldun stated that history can be understood as a recurrence of similar patterns motivated by the drives of acquisition, group co-operation, and regal authority in the creation of a civilisation, followed by a cycle of decay. These primary drives become distorted and lead to the corrupting factors of luxury and domination, irresponsibility of authority and decline.

Like Spengler, in regard to the peasantry, Ibn Khaldun traces the beginning of culture to group or familial loyalty starting with the simple life of the rural - and desert – environments. The isolation and familial bonds lead to self-reliance, loyalty and leadership on the basis of mutual respect. Life is struggle, not luxury. According to Ibn Khaldun, when rulership becomes centralised and divorced from such kinship, free reign is given to luxury and ease. Political alliances are bought and intrigued rather than being based on the initial bonds and loyalties. Corruption pervades as the requirements of luxury increase. The decadence starts from the top, among the ruling class, and extends downward until the founding ethos of the culture is discarded, or exists in name only.

Ibn Khaldun begins from the organic character of the noble family in describing the analogous nature of cultural rise and fall, caused by a falling away of the original creative ethos with each successive generation:

Ibn Khaldun begins from the organic character of the noble family in describing the analogous nature of cultural rise and fall, caused by a falling away of the original creative ethos with each successive generation:

“The builder of the family’s glory knows what it cost him to do the work, and he keeps the qualities that created his glory and made it last. The son who comes after him had personal contact with his father and thus learned those things from him. However, he is inferior to him in this respect, inasmuch as a person who learns things through study is inferior to a person who knows them from practical application. The third generation must be content with imitation and, in particular, with reliance upon tradition. This member is inferior to him of the second generation, inasmuch as a person who relies upon tradition is inferior to a person who exercises judgment.

“The fourth generation, then, is inferior to the preceding ones in every respect. Its member has lost the qualities that preserved the edifice of its glory. He despises those qualities. He imagines that the edifice was not built through application and effort. He thinks that it was something due to his people from the very beginning by virtue of the mere fact of their descent, and not something that resulted from group effort and individual qualities. For he sees the great respect in which he is held by the people, but he does not know how that respect originated and what the reason for it was. He imagines it is due to his descent and nothing else. He keeps away from those in whose group feeling he shares, thinking that he is better than they”.

For Ibn Khaldun’s “generation” we might say with Spengler “cultural epoch”. Ibn Khaldun addresses the causes of this cultural etiolation, leading to the corrupting impact of materialism. Again, his analysis is remarkably similar to that of Spengler and the decay of the Classical civilisations:

“When a tribe has achieved a certain measure of superiority with the help of its group feeling, it gains control over a corresponding amount of wealth and comes to share prosperity and abundance with those who have been in possession of these things. It shares in them to the degree of its power and usefulness to the ruling dynasty. If the ruling dynasty is so strong that no-one thinks of depriving it of its power or of sharing with it, the tribe in question submits to its rule and is satisfied with whatever share in the dynasty’s wealth and tax revenue it is permitted to enjoy. ... Members of the tribe are merely concerned with prosperity, gain and a life of abundance. (They are satisfied) to lead an easy, restful life in the shadow of the ruling dynasty, and to adopt royal habits in building and dress, a matter they stress and in which they take more and more pride, the more luxuries and plenty they acquire, as well as all the other things that go with luxury and plenty.

“As a result the toughness of desert life is lost. Group feeling and courage weaken. Members of the tribe revel in the well-being that God has given them. Their children and offspring grow up too proud to look after themselves or to attend to their own needs. They have disdain also for all the other things that are necessary in connection with group feeling.... Their group feeling and courage decrease in the next generations. Eventually group feeling is altogether destroyed. ... It will be swallowed up by other nations.

Ibn Khaldun refers to the “tribe” and “group feeling” where Spengler refers to nations, peoples, and races. The dominant culture becomes corrupted through its own success and its culture become static; its inward strength diminishes in proportion to its outward glamour. Hence, the Golden Age of Islam is over, as are those of Rome and Athens. New York, Paris, and London are in the analogous cultural epochs to those of Fez, Rome and Athens. The “world city” becomes the focus of a world civilisation that ends as cosmopolitan and far removed from its founding roots. Our present “world-cities’” – in particular, New York and The City of London - are the control centres of world politics, economics, and mass-culture by the fact of their also being the centres of banking. These world-cities are the prototypes for a world civilisation that continues to be called “Western”, under the leadership of the USA, a rotting centre like Fez and Rome.

The Muslim determination of what is “progress” and what is “decline” has a spiritual foundation:

“The progressiveness or backwardness of society at any given point of time is determinable in relative terms. It can be compared to other contemporary societies [like the Spenglerian method] or to its own state in the past. … for Muslim society although economic progress is not frowned upon, it is placed lower on the order of priorities as compared to other factors; e.g. the acquisition of knowledge or the provision of justice. There is also a tradition (Hadis) of the Holy Prophet that lists the symptoms of society that is in a pathological state of decline. These outward symptoms point to an underlying malaise in the society but can also provide a useful starting point for corrective actions for stopping or reversing the onset of decline”. The high and low points of Muslim civilisation can be identified as those of a “Golden Age” or of an “Abyss”.

Comparable to the warnings of other sages, in an epoch of decline again there is an inversion of hierarchy, or more specifically here, of character, the Hadith stating that those in such a society would be corrupted, while others might resist within themselves:

“There will be soon a period of turmoil in which the one who sits will be better than one who stands and the one who stands will be better than one who walks and the one who walks will be better than one who runs. He who would watch them will be drawn by them. So he who finds a refuge or shelter against it should make it as his resort”.

Hebrew “Race”

A Traditionalist “race”, conscious of its nexus with the Divine as the basis of culture, endures regardless of contact with foreigners because of its inward strength. This allows it to accept foreigners not only without weakening the cultural organism but even strengthening it; because it accepts foreign input on its own terms. A Traditionalist “race” surviving over the course of millennia without succumbing to the cyclical laws of decay is the Jewish. They are the Traditionalist “race” par excellence. No better example can be had than this People that has maintained its nexus with its Divinity as the basis of cultural survival, whose religion is a race-founding and race-sustaining mythos.

Contrary to the beliefs of certain racial ideologues, including extreme Zionists and ultra-Orthodox Jews, this survival is not the result of bans on miscegenation. The Jewish law as embodied in the Torah, the first five books of the Old Testament, is based not on zoological race but on a race mythos. The Mosaic Law demands “race purity” in the Traditionalist sense; that of a community of belief in a heritage and a destiny.

Contrary to the beliefs of certain racial ideologues, including extreme Zionists and ultra-Orthodox Jews, this survival is not the result of bans on miscegenation. The Jewish law as embodied in the Torah, the first five books of the Old Testament, is based not on zoological race but on a race mythos. The Mosaic Law demands “race purity” in the Traditionalist sense; that of a community of belief in a heritage and a destiny.

Bizarrely, some white racists have adopted the Torah commandments as being based on genetic purity, in their belief that whites are the true Israelites. For example the priest Phineas, at the time of Moses is held in esteem by such white supremacists because he speared an Israelite and a Midianite in the act of copulation. At this time apparently the Midianites were seducing Israel away from its God, towards Baal. A purge of Israel took place. However the chapter in its entirety makes plain this was a matter of religion, not miscegenation. The nexus between Israel and the Divine was being broken by the influence of “the daughters of Moab.” Israel’s Divinity is recorded as having threatened wrath because of “my insistence on exclusive devotion.” The Divine nexus was established for eternity with the line of Phineas because he had “not tolerated any rivalry towards his god”. Moses himself had married the daughter of a Midianite priest, so the issue with the Midianites was clearly religious, and specifically that such foreign influences would break Israel’s nexus with the Divine that renders them a “special people”. Where marriages with Hittites, Amorites, Canaanites, et al are prohibited it is because this nexus would be subverted. However, in the same book Deuteronomy, where the Israelite war code is being established, when a city has been defeated the adult males are to be eliminated, and the women and children are to be taken to be grafted on to Israel. The commandments for this type of “scorched earth policy” were based on preventing foreigners from teaching Israel their religions. There are precise laws as to marrying a non-Israelitish captive woman, who after a month of mourning for the deaths of her family, will have the marriage consummated and thereby become part of Israel.

Jeremiah (ca. 600 B.C.), son of the high priest Hilkiah, was one of the most significant voices against culture-decay, analogous to Ipuwer the Egyptian sage, Titus Livius, and Cato the Censor, in Rome, and our own Spengler and Evola. He warned that Israel would prosper while the nexus with Tradition and ipso facto with the Divine was maintained; Israel would fall physically if it fell away morally from that Tradition. Jeremiah saw the destruction of the Temple of Solomon and the carrying into Babylonian captivity of Judah. As with the other Civilisations that have fallen, the first symptom had been a subversion of its founding religion. Interestingly, religious decay would be quickly proceeded by an invasion of foreigners, reminiscent of Ipuwer’s warning of Egypt’s invasion by “Asiatics”. Hence, Jeremiah warns that invasion is imminent as a punishment for Israel’s departure from the Traditional faith: “I will pronounce my judgments on my people because of their wickedness in forsaking me, in burning incense to other gods and in worshiping what their hands have made”. From their self-styled role as a Holy People, they had fallen from the oath of their forefathers, Jeremiah/YHWH admonishing: “The priests did not ask, ‘Where is the LORD?’ Those who deal with the law did not know me; the leaders rebelled against me. The prophets prophesied by Baal, following worthless idols. ‘Therefore I bring charges against you again,’ declares the LORD. ‘And I will bring charges against your children’s children’”. Jeremiah states that the priesthood has become corrupted, from whence the rot proceeds downward. “The prophets prophesy lies, the priests rule by their own authority, and my people love it this way. But what will you do in the end?” Specifically, all of Israel had become motivated by greed. The admonition was to stand at the “crossroads” as to what paths to follow, and choose “the ancient paths”.

“From the least to the greatest, all are greedy for gain; prophets and priests alike, all practice deceit. They dress the wound of my people as though it were not serious. ‘Peace, peace,’ they say, when there is no peace. Are they ashamed of their detestable conduct? No, they have no shame at all; they do not even know how to blush. So they will fall among the fallen; they will be brought down when I punish them,” says the LORD. This is what the LORD says: “Stand at the crossroads and look; ask for the ancient paths, ask where the good way is, and walk in it, and you will find rest for your souls. But you said, ‘We will not walk in it’”.

Greed, or what we now call materialism, has been the common factor of the fall of Civilisations, referred to by sages and philosophers up to our own Spengler, Brooks Adams, and Evola. The other common factor, as we have seen, has been the corruption of religion and the priestly caste, the priests and the prophets being condemned by Jeremiah.

The perennial survival of the Israelites is based on their adherence to Tradition. Prophets such as Jeremiah are the Jews’ constant warning to stay true to their “ancient paths” or destruction will result. The Jews worldwide have had, when not a King over Israel, the focus of a coming King-Messiah, Jerusalem, the Ark of the Covenant, and the Temple of Solomon (including the plans to rebuild the Temple as another focus for the future) as their world axial points, and the Mosaic Law as a universal code of living across time and place.These axial points have formed and maintained the Jews as a metaphysical race. Whatever others might think of some of their laws and beliefs their maintenance of a Traditional nexus has allowed them to supersede the cyclic laws of decay perhaps like no other people, to overcome decline and be restored, while paradoxically being the carriers of cultural pathogens among other civilisations (Marxism, Freudianism).

What the genetics of races shows, past and present, is that miscegenation has not been a cause for the collapse of civilisations. Perhaps dysgenics might cause such a collapse, but hitherto there seems scant evidence for it. By focusing to the point of ideological obsession and dogma on the assume causes of culture-death being that of miscegenation, the actual causes are overlooked. Perhaps civilisation, theoretically, might die through dysgenics, whether racial or otherwise, but it seems that before such a dysgenic process has ever taken place the morphological laws of organic life and death have intervened as witnessed by those such as Livy, Cato, Ibn Khaldun, and in our time Spengler, Evola and Brooks Adams.

This publication fills a gap long felt by the many students of the history of religions, since previous editions of the Book of the Dead, this most important document of ancient Egypt, have long been unavailable. The works of Lepsius (1842), Naville (1886), Pierret (1882), Sir Peter Le Page Renouf (1904), and Schiaparelli (1881–1890) can only be found in libraries. The only edition reprinted has been the 1953 edition by E. A. Wallis Budge with facsimiles of the papyri.

This publication fills a gap long felt by the many students of the history of religions, since previous editions of the Book of the Dead, this most important document of ancient Egypt, have long been unavailable. The works of Lepsius (1842), Naville (1886), Pierret (1882), Sir Peter Le Page Renouf (1904), and Schiaparelli (1881–1890) can only be found in libraries. The only edition reprinted has been the 1953 edition by E. A. Wallis Budge with facsimiles of the papyri. Nevertheless, there are many parallel points between the two texts dealing with the liberating identifications. Just as in the Tibetan ritual the destruction of the appearance of distinct entities, which all things perceived in the experiences of the other world may acquire, is indicated as a means of liberation, so in the Egyptian text formulae are repeated by means of which the soul of the dead affirms and realizes its identity with the divine figures.

Nevertheless, there are many parallel points between the two texts dealing with the liberating identifications. Just as in the Tibetan ritual the destruction of the appearance of distinct entities, which all things perceived in the experiences of the other world may acquire, is indicated as a means of liberation, so in the Egyptian text formulae are repeated by means of which the soul of the dead affirms and realizes its identity with the divine figures.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Pourquoi un tel recours au sot savant de Molière ? C’est le nombre de chaînes de télé qui devient prodigieux, confirmant que l’humanité ne fait plus rien : on regarde 6.000 chaînes de télé et on a besoin d’experts sur tous les sujets pour savoir quoi penser en matière de vaccins, de nourriture, de sexe, d’atomisme nord-coréen ou de gamins transgenre.

Pourquoi un tel recours au sot savant de Molière ? C’est le nombre de chaînes de télé qui devient prodigieux, confirmant que l’humanité ne fait plus rien : on regarde 6.000 chaînes de télé et on a besoin d’experts sur tous les sujets pour savoir quoi penser en matière de vaccins, de nourriture, de sexe, d’atomisme nord-coréen ou de gamins transgenre. Le film continue sur sa lancée : l’art moderne avec ses copies indécelables et ses toiles blanches ; la météo avec son réchauffement climatique ; la bourse, bien sûr, avec la fameuse parabole du singe qui ne se trompe pas plus qu’un analyste payé des fortunes.

Le film continue sur sa lancée : l’art moderne avec ses copies indécelables et ses toiles blanches ; la météo avec son réchauffement climatique ; la bourse, bien sûr, avec la fameuse parabole du singe qui ne se trompe pas plus qu’un analyste payé des fortunes.

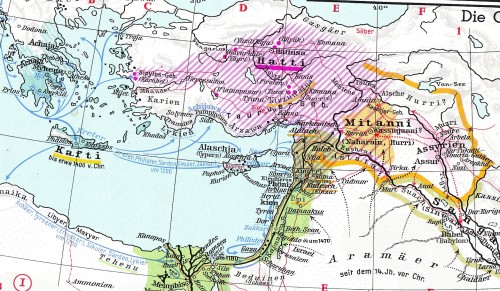

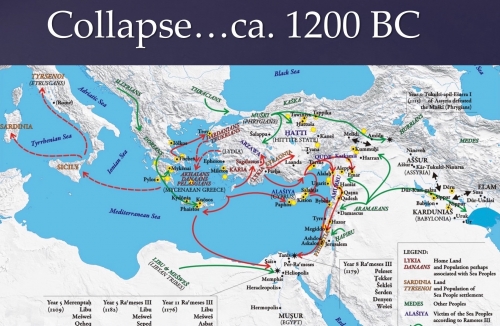

From about 1500 BC to 1200 BC, the Mediterranean region played host to a complex cosmopolitan and globalized world-system. It may have been this very internationalism that contributed to the apocalyptic disaster that ended the Bronze Age. When the end came, the civilized and international world of the Mediterranean regions came to a dramatic halt in a vast area stretching from Greece and Italy in the west to Egypt, Canaan, and Mesopotamia in the east. Large empires and small kingdoms collapsed rapidly. With their end came the world’s first recorded Dark Ages. It was not until centuries later that a new cultural renaissance emerged in Greece and the other affected areas, setting the stage for the evolution of Western society as we know it today. Professor Eric H. Cline of The George Washington University will explore why the Bronze Age came to an end and whether the collapse of those ancient civilizations might hold some warnings for our current society.

From about 1500 BC to 1200 BC, the Mediterranean region played host to a complex cosmopolitan and globalized world-system. It may have been this very internationalism that contributed to the apocalyptic disaster that ended the Bronze Age. When the end came, the civilized and international world of the Mediterranean regions came to a dramatic halt in a vast area stretching from Greece and Italy in the west to Egypt, Canaan, and Mesopotamia in the east. Large empires and small kingdoms collapsed rapidly. With their end came the world’s first recorded Dark Ages. It was not until centuries later that a new cultural renaissance emerged in Greece and the other affected areas, setting the stage for the evolution of Western society as we know it today. Professor Eric H. Cline of The George Washington University will explore why the Bronze Age came to an end and whether the collapse of those ancient civilizations might hold some warnings for our current society.

French and English racism was introduced to Germany by the Englishman Houston Stewart Chamberlain who had a seminal influence on Hitlerism. English Darwinism, a manifestation of the materialistic Zeitgeist that dominated England, was brought to Germany by Ernst Haeckel; although Blumenbach had already begun to classify race according to cranial measurements during the 18th century. Nonetheless, biological racism reflects the English Zeitgeist of materialism. It provided primary materialistic doctrines to dethrone Tradition. Its application to economics also provided a scientific justification for the “class struggle” of both the capitalistic and socialistic varieties. Hitlerism was an attempt to synthesis the English eugenics of Galton and the evolution of Darwin with the metaphysis of German Idealism. Italian Traditionalist Julius Evola attempted to counter the later influence of Hitlerian racism on Italian Fascism by developing a “metaphysical racism,” and the concept of the “race of the spirit,” which has its parallels in Spengler, whose approach to race is in the Traditionalist mode of the German Idealists.

French and English racism was introduced to Germany by the Englishman Houston Stewart Chamberlain who had a seminal influence on Hitlerism. English Darwinism, a manifestation of the materialistic Zeitgeist that dominated England, was brought to Germany by Ernst Haeckel; although Blumenbach had already begun to classify race according to cranial measurements during the 18th century. Nonetheless, biological racism reflects the English Zeitgeist of materialism. It provided primary materialistic doctrines to dethrone Tradition. Its application to economics also provided a scientific justification for the “class struggle” of both the capitalistic and socialistic varieties. Hitlerism was an attempt to synthesis the English eugenics of Galton and the evolution of Darwin with the metaphysis of German Idealism. Italian Traditionalist Julius Evola attempted to counter the later influence of Hitlerian racism on Italian Fascism by developing a “metaphysical racism,” and the concept of the “race of the spirit,” which has its parallels in Spengler, whose approach to race is in the Traditionalist mode of the German Idealists. Julius Evola, while repudiating the zoological primacy of “racism” as another form of materialism and therefore anti-Traditional, suggested that a “spiritual racism” is necessary to oppose the forces seeking to turn man into an amorphous mass; as interchangeable economic units without roots; what is now called “globalisation”.

Julius Evola, while repudiating the zoological primacy of “racism” as another form of materialism and therefore anti-Traditional, suggested that a “spiritual racism” is necessary to oppose the forces seeking to turn man into an amorphous mass; as interchangeable economic units without roots; what is now called “globalisation”.  Here Livy is observing that occupiers among foreign peoples “go native”, as one might say. The occupiers are pulled downward, rather than elevating their subjects upward, not through genetic contact but through moral and cultural corruption. The Syrians, Parthians and Egyptians, had already become historically and culturally passé, or Fellaheen, as Spengler puts it. The Macedonian Greeks in those colonies succumbed to the force of etiolation. Alexander even encouraged this in an effort to meld all subjects into one Greek mass, which resulted not from a Hellenic civilisation passed along by multitudinous peoples, but in a chaotic mass from which Greece did not recover, despite the Greeks staying racially intact. Unlike the Jews in particular, the Greeks, Romans and other conquerors did not have the strength of Tradition to maintain themselves among alien cultures. Dr. W. W. Tarn stated of this process:

Here Livy is observing that occupiers among foreign peoples “go native”, as one might say. The occupiers are pulled downward, rather than elevating their subjects upward, not through genetic contact but through moral and cultural corruption. The Syrians, Parthians and Egyptians, had already become historically and culturally passé, or Fellaheen, as Spengler puts it. The Macedonian Greeks in those colonies succumbed to the force of etiolation. Alexander even encouraged this in an effort to meld all subjects into one Greek mass, which resulted not from a Hellenic civilisation passed along by multitudinous peoples, but in a chaotic mass from which Greece did not recover, despite the Greeks staying racially intact. Unlike the Jews in particular, the Greeks, Romans and other conquerors did not have the strength of Tradition to maintain themselves among alien cultures. Dr. W. W. Tarn stated of this process: “In our time all Greece was visited by a dearth of children and generally a decay of population, owing to which the cities were denuded of inhabitants, and a failure of productiveness resulted, though there were no long-continued wars or serious pestilences among us. If, then, any one had advised our sending to ask the gods in regard to this, what we were to do or say in order to become more numerous and better fill our cities,—would he not have seemed a futile person, when the cause was manifest and the cure in our own hands? For this evil grew upon us rapidly, and without attracting attention, by our men becoming perverted to a passion for show and money and the pleasures of an idle life, and accordingly either not marrying at all, or, if they did marry, refusing to rear the children that were born, or at most one or two out of a great number, for the sake of leaving them well off or bringing them up in extravagant luxury. For when there are only one or two sons, it is evident that, if war or pestilence carries off one, the houses must be left heirless: and, like swarms of bees, little by little the cities become sparsely inhabited and weak. On this subject there is no need to ask the gods how we are to be relieved from such a curse: for any one in the world will tell you that it is by the men themselves if possible changing their objects of ambition; or, if that cannot be done, by passing laws for the preservation of infants”.

“In our time all Greece was visited by a dearth of children and generally a decay of population, owing to which the cities were denuded of inhabitants, and a failure of productiveness resulted, though there were no long-continued wars or serious pestilences among us. If, then, any one had advised our sending to ask the gods in regard to this, what we were to do or say in order to become more numerous and better fill our cities,—would he not have seemed a futile person, when the cause was manifest and the cure in our own hands? For this evil grew upon us rapidly, and without attracting attention, by our men becoming perverted to a passion for show and money and the pleasures of an idle life, and accordingly either not marrying at all, or, if they did marry, refusing to rear the children that were born, or at most one or two out of a great number, for the sake of leaving them well off or bringing them up in extravagant luxury. For when there are only one or two sons, it is evident that, if war or pestilence carries off one, the houses must be left heirless: and, like swarms of bees, little by little the cities become sparsely inhabited and weak. On this subject there is no need to ask the gods how we are to be relieved from such a curse: for any one in the world will tell you that it is by the men themselves if possible changing their objects of ambition; or, if that cannot be done, by passing laws for the preservation of infants”. Alien immigration introduces cultural elements that dislocate the social and ethical basis of a Civilisation and aggravate an existing pathological condition. The English scholar Professor C. Northcote Parkinson, writing on the fall of Rome, commented that the Roman conquerors were subjected “to cultural inundation and grassroots influence”. Because Rome extended throughout the world, like the present Late Western, the economic opportunities accorded by Rome drew in all the elements of the subject peoples, “groups of mixed origin and alien ways of life”. “Even more significant was what the Romans learnt while on duty overseas, for men so influenced were of the highest rank”. Parkinson quotes Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, referring to the Roman colony of Antioch:

Alien immigration introduces cultural elements that dislocate the social and ethical basis of a Civilisation and aggravate an existing pathological condition. The English scholar Professor C. Northcote Parkinson, writing on the fall of Rome, commented that the Roman conquerors were subjected “to cultural inundation and grassroots influence”. Because Rome extended throughout the world, like the present Late Western, the economic opportunities accorded by Rome drew in all the elements of the subject peoples, “groups of mixed origin and alien ways of life”. “Even more significant was what the Romans learnt while on duty overseas, for men so influenced were of the highest rank”. Parkinson quotes Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, referring to the Roman colony of Antioch:

What is notable is not that the Romans miscegenated with Orientals, but that the uprooted, amorphous masses of the cities no longer adhered to the Traditions on which Roman civilisation was founded. The same process can be seen today at work in New York, London and Paris. Duff wrote of this, and we might consider the parallels with our own time:

What is notable is not that the Romans miscegenated with Orientals, but that the uprooted, amorphous masses of the cities no longer adhered to the Traditions on which Roman civilisation was founded. The same process can be seen today at work in New York, London and Paris. Duff wrote of this, and we might consider the parallels with our own time:  India is the most commonly cited example of a civilisation that decayed through miscegenation, the invading Aryans imparting a High Culture on India and then forever falling into decay because of miscegenation with the low caste “blacks”, or Dravidians. However, Genetic research indicates that the higher castes have retained to the present a predominately Caucasian genetic inheritance.