mardi, 03 mai 2022

La Chine et l'ancrage post-léniniste

La Chine et l'ancrage post-léniniste

Markku Siira

Source: https://markkusiira.com/2022/04/25/kiina-ja-leninismin-ja...

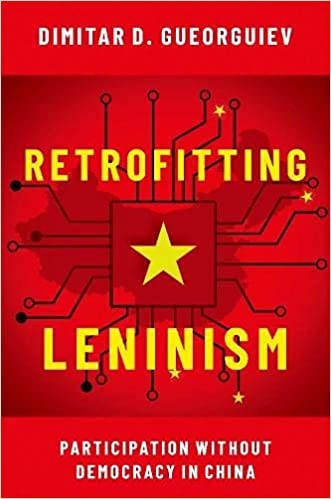

Le livre de Dimitar D. Gueorguiev, Retrofitting Leninism : Participation Without Democracy in China (Oxford University Press, 2021) explique comment, en Chine, le gouvernement ouvert et les technologies modernes de l'information se combinent pour maintenir un système contrôlé mais socialement réactif.

La République populaire de Chine est une exception notable parmi les régimes autoritaires. Alors que les systèmes fermés échouent souvent et finissent par s'effondrer à mesure qu'ils se réforment et s'ouvrent, le Parti communiste a réussi son développement, tout en conservant le respect de la majorité du peuple.

Gueorguiev, professeur associé de sciences politiques à l'université de Syracuse aux Etats-Unis et chercheur du Wilson Center sur la Chine, propose dans son livre une explication fondée sur des données empiriques. Il affirme que la clé de la capacité du parti communiste à se maintenir au pouvoir réside dans sa capacité à combiner le contrôle autoritaire avec l'inclusion sociale - un processus facilité par la technologie moderne des télécommunications.

En s'appuyant sur des données statistiques, des rapports médiatiques et des sondages d'opinion originaux, Gueorguiev a examiné comment l'opinion publique influence le contrôle politique et l'élaboration des politiques. Dans son livre, il analyse la représentation et la coordination ascendantes dans les législatures locales de Chine.

L'ombre de l'idéologue communiste révolutionnaire Vladimir Lénine se profile à l'arrière-plan. Les régimes léninistes qui ont émergé au début du 20e siècle ont mis en avant un intérêt pour la participation de la base. Le désir d'exploiter la contribution des citoyens au contrôle et à la planification bureaucratiques était un pilier fondamental de la pensée marxiste-léniniste et le cœur de la philosophie politique maoïste.

À cet égard, la technologie moderne offre des avantages considérables pour que l'administration reste à jour et prenne le pouls du pays. En effet, Gueorguiev soutient que l'intérêt du parti communiste pour la gouvernance participative reflète une tentative d'actualiser les mécanismes de la gouvernance léniniste, un processus que l'auteur appelle "retrofitting" dans le titre de son livre.

Lénine s'opposait au multipartisme démocratique, qu'il considérait comme un "pas en arrière" sur la voie de la révolution. De plus, l'avantage du régime chinois, effectivement à parti unique, est "la capacité de réfléchir au passé et au présent, et de planifier à long terme sans avoir à tenir compte des transitions politiques ou idéologiques de routine".

Gueorguiev affirme également que le parti communiste considère souvent son passé et son avenir à travers un "prisme d'incertitude politique", en raison de l'expérience de la révolution culturelle (1966-1974) et, dans une moindre mesure, de la première décennie d'ouverture et de réforme (1979-1989).

Pendant la Révolution culturelle, la société civile a été ébranlée par le culte de la personnalité et la ferveur idéologique, qui ont amené le système au bord de l'effondrement total. Dans la Chine contemporaine, les succès et les échecs de l'ère Mao font déjà l'objet d'une évaluation critique.

À la fin des années 1980, la décentralisation et la privatisation ont sapé les plates-formes juridiques et de protection sociale des citoyens ordinaires, créant une pression ascendante et un besoin pour le régime de répondre aux griefs signalés.

Le gouvernement chinois actuel veut éviter la répétition de ces deux erreurs. Les citoyens peuvent déposer des plaintes, des pétitions, fournir des tuyaux sur la corruption et commenter la législation en cours via Internet. M. Gueorguiev estime que les canaux en ligne aideront le régime à affiner ses politiques et à accroître sa légitimité.

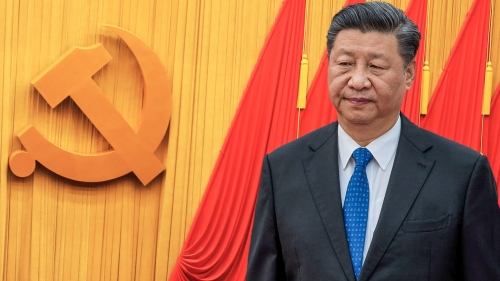

Avant tout, le parti communiste chinois est capable de contenir et d'exploiter les tensions sociales par le biais d'une participation non politique et de la technologie. Au cours de l'épidémie du coronavirus de ces dernières années, le régime de Xi Jinping a également cherché à démontrer son efficacité face au défi sanitaire en appliquant une "stratégie corona zéro", assortie de confinements stricts.

L'exemple le plus significatif de la révolution technologique dans la gouvernance chinoise est sans doute le nouveau système de notation du crédit social, qui a fait sensation en Occident et qui, selon Gueorguiev, est "une excroissance de la vision léniniste séculaire du contrôle informé".

Le système de notation de crédit est destiné à aider le gouvernement à surmonter les faiblesses systémiques dans un certain nombre de domaines, notamment un système bancaire d'État hypertrophié et obsolète et une infrastructure de protection des consommateurs sérieusement défectueuse.

Les droits des citoyens et le statut social ne sont pas affectés de la même manière que ce qui est souvent sensationnalisé en Occident. Les autorités chinoises ont déclaré, lors de la phase pilote du projet, que le système de notation ne pouvait pas être utilisé pour punir les citoyens, mais que cela se ferait dans le cadre de la législation existante.

Les innovations numériques en matière de gestion de l'information peuvent encourager les dirigeants à envisager une répression ciblée comme alternative aux dépenses sociales à grande échelle. Cela est sans doute attrayant d'un point de vue autoritaire, mais s'il est mal utilisé, il pourrait saper l'autorité des personnes au pouvoir. À cet égard, la numérisation du contrôle de l'information offre des possibilités de contrôle accru, mais aussi des risques.

Une façon de se prémunir contre cette éventualité est de fixer des objectifs audacieux, tels que le plan annoncé par le Parti communiste pour éradiquer la pauvreté, développer les systèmes publics de soins de santé et de retraite, et passer très rapidement des combustibles fossiles aux énergies renouvelables.

Certains de ces objectifs ont déjà été atteints. La Chine est sortie des rangs des pays les plus pauvres et les moins développés du monde pour devenir un rival économique des États-Unis. Dans toute la Chine, les industries et les communautés se modernisent à un rythme sans précédent et les investissements ont augmenté, si bien que les économies de certaines villes chinoises rivalisent déjà avec celles de nombreux petits et même moyens pays.

Bien que l'on ne sache toujours pas si la Chine s'oriente de plus en plus vers une technocratie très au point, une idéologie mixte confucéenne-communiste, ou les deux, il est clair que ceux qui ont interprété les réformes participatives de la Chine comme menant à une "démocratisation" de style occidental ont été cruellement déçus.

En effet, tout au long du livre, Gueorguiev souligne que la participation publique en Chine maintient et affine le contrôle politique. La logique organisationnelle qui sous-tend la participation de masse dans la République populaire de Chine contemporaine assure également le cloisonnement des masses, la démobilisation politique et, plus largement, le contrôle du parti.

Dans la mesure où la complémentarité de la participation et du contrôle améliore encore la gouvernance, elle renforce la sécurité du régime au pouvoir. En effet, la Chine semble aujourd'hui plus éloignée de la démocratie qu'elle ne l'était il y a vingt, trente ou même quarante ans. Ainsi, l'idée que la Chine, en se modernisant, deviendra une démocratie libérale aux caractéristiques chinoises a peu de chances de se concrétiser.

S'il est facile de critiquer la techno-société autoritaire de la Chine, il ne faut pas ignorer la possibilité qu'un État de surveillance chinois favorise une meilleure gouvernance, le respect des règles et une société plus organisée en général. Il s'agit, en fait, d'un objectif déclaré du régime chinois, qui a également été implicitement accepté par ses citoyens.

Avec l'effondrement de l'Union soviétique en 1991, la Chine est devenue le régime socialiste le plus important dans un monde dominé par les démocraties occidentales. Il est compréhensible que dans les pays en développement, par exemple, il existe un intérêt pour une alternative aux modèles de gouvernance occidentaux. Pékin affirme toutefois que sa révolution nationale n'est pas un produit d'exportation au même titre que la "démocratie" américaine.

La modernisation et le développement technologique de la Chine ont contribué à améliorer le régime autoritaire, rapprochant la République populaire de Chine de la vision technocratique de ses origines léninistes et d'une "dictature du prolétariat" actualisée. M. Gueorguiev estime que le "modèle chinois" est susceptible de susciter l'intérêt d'autres États axés sur le contrôle.

L'exemple chinois sert de contrepoids puissant à l'argument selon lequel l'intervention de l'État et la modernisation économique sont incompatibles. De même, pour ceux qui s'inquiètent de la montée du populisme démocratique, l'approche technocratique de la Chine est naturellement attrayante.

À ce stade, il convient toutefois de souligner que la technocratie de l'Occident, un système dirigé par de riches oligarques, n'est pas une imitation du "socialisme" chinois, mais le même capitalisme d'exploitation transnational avec un vernis technologique. En Occident, l'intérêt se limite aux diverses possibilités de la numérisation, et non au "socialisme avec des caractéristiques nationales".

L'étude de Gueorguiev sur "l'autoritarisme participatif" de la Chine montre comment le modèle léniniste est mis en pratique dans la Chine contemporaine, en utilisant la haute technologie et l'activation des citoyens. En même temps, il offre un regard intéressant sur la gouvernance chinoise et les perspectives d'avenir.

J'ai été amené à m'interroger sur l'impact de la technocratie sur la politique. De telles évolutions, avec leurs technologies d'IA et leurs algorithmes - "l'automatisation réussie du léninisme" mentionnée par Gueorguiev - pourraient-elles un jour rendre les partis politiques et les idéologies sans intérêt, tout comme l'automatisation et la robotique rendent superflus un grand nombre de travailleurs ?

19:02 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, chine, asie, affaires asiatiques, participation chinoise, léninisme, postléninisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 04 décembre 2020

Revolution as Profession

Revolution as Profession

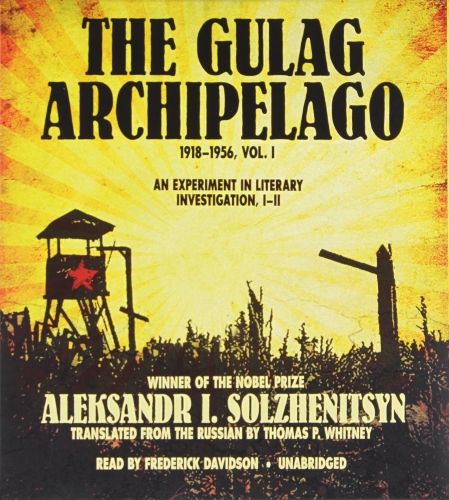

When the historian Ernst Nolte formulated the thesis that Auschwitz was “the fear-induced reaction to the extermination processes of the Russian Revolution,” he was finished in the academic world. It was even of no help to him emphasizing that the copy was more irrational, more appalling and atrocious than the original. He was not forgiven the comparison since he seemed to call into question the singularity thesis, the incomparability of NS terror. That fit the taboo on totalitarianism theory. Right-wing and left-wing terror should not be mentioned in the same breath; National Socialism and International Socialism are not to be compared. And therefore all attempts to similarly work through the reign of terror by the Communists in its broad impact, as has been done with that of the Nazis, have been in vain. Of course, one would have to differentiate here. French intellectuals have undoubtedly been affected by the shocking reports by Koestler and Solzhenitsyn about the Moscow Trials and the Gulag. That was, at best, embarrassing for the German left. And so it should be no surprise that it celebrated Lenin’s 150th birthday—though under coronavirus conditions.

Lenin was the star of the Bolsheviks, who understood themselves to be the Jacobins of the twentieth century. He was undoubtedly an exceptionally gifted demagogue, but one should not imagine the Russian Revolution as resulting from a social movement; it was a project of intellectuals. The Bolshevik vanguard consisted of theorists, frequently emigrants, who had learned from Marx to use Hegel’s dialectic as a weapon. In this respect, the neo-Marxist bible History and Class Consciousness (1923) by Georg Lukács is still today unsurpassed. Here Hegel’s adroit dictum “all the worse for the facts” is taken seriously: more real than the facts is the totality as it presents itself from the standpoint of the proletarian class. In this way, dialectics becomes opium for the intellectuals.

Like the French Revolution, the Russian is also marked by an alliance of philosophy with fanatical enthusiasm. And this fanaticism of the Lenin cult has found its intellectual fans up into the present—one thinks of the hypersensitive aesthetician Walter Benjamin, of the communist model poet Bert Brecht, of the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, then the student movement of ’68 and the present-day left. We owe the most extreme formulation of the cult to Ernst Bloch: “Ubi Lenin, ibi Jerusalem,” where Lenin is, there is salvation, the kingdom of freedom and eternal childhood in God. Ernst Nolte was thus right when he characterized Marxism as “the last faith in Europe.” And this faith was “organized” by Lenin.

Like the French Revolution, the Russian is also marked by an alliance of philosophy with fanatical enthusiasm. And this fanaticism of the Lenin cult has found its intellectual fans up into the present—one thinks of the hypersensitive aesthetician Walter Benjamin, of the communist model poet Bert Brecht, of the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, then the student movement of ’68 and the present-day left. We owe the most extreme formulation of the cult to Ernst Bloch: “Ubi Lenin, ibi Jerusalem,” where Lenin is, there is salvation, the kingdom of freedom and eternal childhood in God. Ernst Nolte was thus right when he characterized Marxism as “the last faith in Europe.” And this faith was “organized” by Lenin.

The central Leninist dogma was that of the actuality of revolution; it was on the agenda. The suggestive project formula was: “electrification plus soviets.” The revolutionary project was thus constructed like an ellipse around two focal points, the industrialization of agrarian Russia and secondly radical democracy: “All power to the councils.” However, a Soviet Union in the literal sense never quite existed. The Soviet myth was never anything other than opium for the people. For Lenin had designs all along on a dictatorship of the party. It owes its vanguardist self-image as the embodiment of proletarian class consciousness to strict organization and sharp selection. It not only claims to make the proletarians conscious of their true interests, but claims, as well, to be the leader of all the oppressed. With this noble claim, an elite cadre party legitimizes its totalitarian rule. Thus characteristic of the Russian Revolution was not the spontaneity of the masses but authoritarian leadership. From the outset, the dictatorship of the proletariat was a dictatorship of the bureaucracy. The Bolshevist elite had the utmost mistrust of the chaotic people, who were to be transformed into an alliance of the oppressed, organized by fanatical intellectuals. And for this reason we can say today: Lenin is current in a baleful sense, as long as the thought of a revolutionary dictatorship lives on—as long as there are parties that understand themselves as the embodiment of the truth and abuse the state as a weapon.

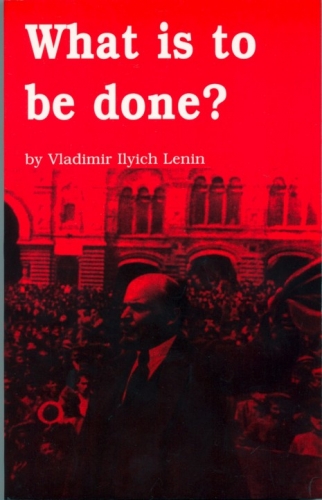

Revolutionary vanguard, Bolshevist elite, cadre party—what inspires these concepts is the notion of revolution as a profession. In his pamphlet “What Is to Be Done?” from the year 1902, Lenin also presents us with the figure of the professional revolutionary. His living existence is party work. Lukács’s Lenin apology went on to further elaborate the theoretical ideal of the sacrificial professional revolutionary in the interest of humanity. As a fanatical Jacobin, he enters the stage of world history for the first time. Yet has one really to imagine the professional revolutionary as an engaged, ascetic fighter? Hannah Arendt drew an entirely different picture: “His time is essentially filled with study and contemplation, with theories and discussions, and of course with reading newspapers, and the sole object of all these purely mental activities is the study of revolutions. The history of the professional revolutionary in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries belongs in truth neither to the history of the working nor the owning classes, but surely to the as yet unwritten history of productive idleness.” What drives the professional revolutionary is therefore not the suffering of the oppressed, but the bohemians’ hatred for the bourgeoisie. The profession of revolution is held by those who have no profession and who stylize, as an aesthetic-political posture, their ressentiment against achievement.

One could speak of a birth of Red Terror from the spirit of dialectical philosophy—of a transition of the bohemian attitude into “merciless mass terror.” Lenin demonstrated that the absolute terror of Jacobin rule could be exceeded, namely, by the radical destruction of the bourgeoisie. Here Marxist class struggle assumes the character of an absolute antagonism. The struggle against the class enemy escalates to a war against monsters. Thus Lenin preached civil war and the necessity of violence. This makes him to the present day one of the most important theoreticians of partisan struggle and guerrilla warfare. For Lenin, an avid reader of Clausewitz, not only war but above all civil war marked the continuation of politics. In this way, even the completely non-Marxist Russian Sonderweg to communism could be justified. Class warfare came to replace for him the crisis of capitalist society. He construed World War I as the result of capitalist collapse and as a historical sign of world revolution.

Anyone who did not share the red belief in the actuality of revolution already came to feel the horror of totalitarian rule in Lenin’s time. There were camps for regime opponents, pogroms against religious believers, and concentration camps for the class enemy. Anyone who opposed the Bolshevist elite was considered a criminal, strikes were considered treason, and every critic was treated as an enemy. That expressions of free speech were prohibited was then self-evident. Stalin only had to systemize this. In the course of the Great Purge, the “enemy of the people” gradually replaced the class enemy. And enemies of the people could indeed also be found within one’s own ranks; they all disappeared in the Gulag. And there, “counter-revolutionaries” were treated even more cruelly than criminals. In 1949 Arthur Koestler, who was himself from 1931 to 1937 a member of the CP, could write in summary: “It is a fact that Stalinism has transformed itself into a movement of the most extreme right over the course of the last 20 years, in accord with established criteria: chauvinism, expansionism elevated to the extreme, a police regime without habeas corpus, monopolization of the means of production by a corrupt hereditary oligarchy, oppression of the masses, elimination of all opposition, abolition of civil and individual rights.” In plain words: with the Great Purge, the red terror culminates in right-wing extremism. A clearer confirmation of totalitarianism theory is not even conceivable. Mussolini and Lenin, Hitler and Stalin were ideological doubles.

Hardly any other book has more strongly altered the European view of the Soviet Union than The Gulag Archipelago by Solzhenitsyn. Through its countless witness testimonies, it has the distinction of being authentic. But one can best gain an impression of the Leninist-Stalinist system by reading Koestler’s Darkness at Noon and Orwell’s 1984. For at issue is not only physical but also psychological cruelty of unimaginable dimensions. What is meant here are show trials, confessions of guilt extracted under torture, and self-incriminations preceded by thorough brainwashing.

We in Germany know show trials primarily through the film footage documenting how in the early 1940s Roland Freisler, president of the People’s Court of Justice, handed down death sentences that had already been determined. These trials were aggressive humiliations in which the defendants were granted no right to a defense. The prototype of such trials was established by the Moscow Trials from 1936 to 1938, in the course of which nearly the entire leadership of the October Revolution was liquidated. One did not shrink from torture to produce “confessions of guilt.” Like Leon Feuchtwanger, Ernst Bloch was also among the intellectuals who justified these Moscow show trials. But the liquidation of the “enemies of the people” did not suffice those in power. The memory of the “non-persons” was also to be wiped out. Several retouched photos of Lenin and Stalin became famous precisely because of this.

The self-incriminations before the tribunals, which were not forced by torture, but also those in numerous writings of communist intellectuals, belong to the great moral scandals of history. One understands them better when one sees how Bolshevism abrogated the moral verities of bourgeois society. Lukács spoke of a “second ethics” that would forcibly and cruelly create clarity in the confused world of the humane. The terrorist is the Gnostic of the deed, who takes crime upon himself as a necessity in the struggle against capitalism. Lukács dedicated his essay “Tactics and Ethics” to the young generation of the Communist Party: the terrorist as hero sacrifices his ego on the altar of the idea that presents itself as an order issued from the world historical situation. And in a letter to Paul Ernst from May 4, 1915, one reads about the revolutionary: “Here—to save the soul—the soul itself must be sacrificed: one must, out of a mystical ethics, become a cruel political realist.” Such is in keeping with the syndrome that Manès Sperber called treason out of loyalty, that is, denial of one’s own standards and convictions, intellectual masochism, and obsequious ingratiation with the “working class.”

The self-incriminations before the tribunals, which were not forced by torture, but also those in numerous writings of communist intellectuals, belong to the great moral scandals of history. One understands them better when one sees how Bolshevism abrogated the moral verities of bourgeois society. Lukács spoke of a “second ethics” that would forcibly and cruelly create clarity in the confused world of the humane. The terrorist is the Gnostic of the deed, who takes crime upon himself as a necessity in the struggle against capitalism. Lukács dedicated his essay “Tactics and Ethics” to the young generation of the Communist Party: the terrorist as hero sacrifices his ego on the altar of the idea that presents itself as an order issued from the world historical situation. And in a letter to Paul Ernst from May 4, 1915, one reads about the revolutionary: “Here—to save the soul—the soul itself must be sacrificed: one must, out of a mystical ethics, become a cruel political realist.” Such is in keeping with the syndrome that Manès Sperber called treason out of loyalty, that is, denial of one’s own standards and convictions, intellectual masochism, and obsequious ingratiation with the “working class.”

So this is the real answer to the question “What is to be done?” Even if Stalin and Mao then surpassed him—Lenin set standards in revolutionary inhumanity. He stood against everything that state policy in the modern era was supposed to accomplish until now: namely, to prevent civil war, to bracket war, and to still see in the enemy human beings. For Lenin, good was everything that demolished bourgeois society. Whoever celebrates him is therefore either ignorant or malicious. One should treat Lenin’s birthday with the same tabooed reticence as April 20th.

00:37 Publié dans Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : théorie politique, révolution, révolutionnaires, lénine, léninisme, communisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook