Jason Reza Jorjani

World State of Emergency [2]

London: Arktos Media, 2017

Dr. Yen Lo: ”You must try, Comrade Zilkov, to cultivate a sense of humor. There’s nothing like a good laugh now and then to lighten the burdens of the day. [To Raymond] Tell me, Raymond, do you remember murdering Mavole and Lembeck?”[1] [3]

If Dr. Jason Jorjani were an inanimate object, he would be an exploding cigar; or perhaps one of those cartoon guns with a barrel that twists around [4] and delivers a blast to the man behind the trigger.[2] [5] Jorjani, however, is neither a gun nor a cigar, but an author, and with his new book he delivers another kind of unexpected explosion of conventional — albeit alt-Right — expectations. Anyone possessed with the least amount of intellectual curiosity — and courage — needs to read this book; although you should keep well away from windows and beloved china, as you will likely want to hurl it away from time to time.

After the twin hammer blows of first, publishing Prometheus and Atlas (London: Arktos, 2016), and then almost immediately taking on the job of Editor-in-Chief at Arktos itself, Jorjani has symmetrically one-upped himself by almost simultaneously resigning from Arktos and unleashing a second book, World State of Emergency, the title of which represents, he tells us almost right at the start, his “concept for a state of emergency of global scope that also demands the establishment of a world state.”[3] [6]

It’s no surprise that there hasn’t been much change here, but a glance at his resignation statement — helpfully posted at his blog[4] [7] — shows that he has set his sights on new targets, and changed his focus from how we got here to where we — might? must? — be going.

In my view, the seismic political shift that we are shepherding, and the Iranian cultural revolution that underlies it, represents the best chance for the most constructive first step toward the Indo-European World Order that I conceptualize in my new book, World State of Emergency.

Another change is that unlike his previous book, where the length and variety made it a bit difficult to keep the thread of the argument before one’s mind, this work is relatively straightforward. In fact, he provides an admirably clear synopsis right at the start, and by Ahura Mazda he sticks to it.

Over the course of the next several decades, within the lifespan of a single generation, certain convergent advancements in technology will reveal something profound about human existence. Biotechnology, robotics, virtual reality, and the need to mine our Moon for energy past peak oil production, will converge in mutually reinforcing ways that shatter the fundamental framework of our societies.

It is not a question of incremental change. The technological apocalypse that we are entering is a Singularity that will bring about a qualitative transformation in our way of being. Modern socio-political systems such as universal human rights and liberal democracy are woefully inadequate for dealing with the challenges posed by these developments. The technological apocalypse represents a world state of emergency, which is my concept for a state of emergency of global scope that also demands the establishment of a world state.

An analysis of the internal incoherence of both universal human rights and liberal democracy, especially in light of the societal and geopolitical implications of these technologies, reveals that they are not proper political concepts for grounding this world state. Rather, the planetary emergency calls for worldwide socio-political unification on the basis of a deeply rooted tradition with maximal evolutionary potential. This living heritage that is to form the ethos or constitutional order of the world state is the Aryan or Indo-European tradition shared by the majority of Earth’s great nations — from Europe and the Americas, to Eurasia, Greater Iran, Hindu India, and the Buddhist East.

In reviewing Jorjani’s previous book [8], Prometheus and Atlas, I said that it could serve as a one-volume survey of the entire history of Western thought, thus obviating the need to waste time and money in one of the collegiate brainwashing institutes; I also said that “the sheer accumulation of detail on subjects like parapsychology left me with the feeling of having been hit about the head with a CD set of the archives of Coast to Coast AM.”

The new book changes its focus to technology and its geopolitical implications, but a bit of the same problem remains, on a smaller scale and, as I said, the overall structure of the argument is clear. In the first chapter, Jorjani lands us in media res: the Third World War. Unlike the last two, most people don’t even realize it’s happening, because this is a true world war, a “clash of civilizations” as Samuel Huntington has famously dubbed it.

The dominance of Western values after the Second World War was a function of the West’s overwhelming military and industrial power; the ease which that power gave to the West’s imposition of its values misled it into thinking those values were, after all, simply “universal.” With the decline of that power, challenges have emerged, principally from the Chinese and Muslim sectors.

Jorjani easily shows that the basis of the Western system — the UN and its supposed Charter of Universal Human Rights — is unable to face these challenges; it is not only inconsistent but ultimately a suicide pact: a supposed unlimited right to freedom of religion allows any other right (freedom from slavery, say, or from male oppression) to be checkmated.

Chapter Two looks at the neocon/neoliberals’ prescription for an improved world order, the universalizing of “liberal democracy.” Here again, Jorjani easily reveals this to be another self-defeating notion: liberalism and democracy are separate concepts, which history shows can readily be set to war with each other, and Moslem demographics alone predicts that universal democracy would bring about the end of liberalism (as it has wherever the neocon wars have brought “democracy”).[5] [9]

For a more accurate and useful analysis, Jorjani then pivots from these neo nostrums to the truly conservative wisdom of the alt-Right’s political guru, Carl Schmitt.

Schmitt’s concept of the state is rooted in Heraclitus: the state emerges (note the word!) not from the armchair speculations of political philosophers on supposed abstract “rights,” but from

Decisive action required by a concrete existential situation, namely the existence of a real enemy that poses a genuine threat to one’s way of life.

Thus, there cannot be a “universal” state: the state must be grounded in the ethos or way of life of a particular people, from which it emerges; and it does so in the state of emergency, when the people confronts an existential Enemy. Unless . . .

Humanity as a whole were threatened by a non-human, presumably extraterrestrial, enemy so alien that in respect to it “we” recognized that we do share a common way of life that we must collectively defense against “them.”[6] [10]

There it is — bang! Just as Jorjani found a passage in Heidegger’s seminar transcripts that he could connect to the world of the paranormal,[7] [11] he grabs hold of this almost off-hand qualification and runs for daylight with it.

We have in interplanetary conflict a threat to Earth as a whole, which according to the logic of Schmitt’s own argument ought to justify a world sovereign. This is even more true if we substitute his technological catalyst[8] [12] with the specter of convergent advancements in technology tending towards a technological singularity, innovations that do not represent merely incremental or quantitative change but qualitatively call into question the human form of life as we know it. This singularity would then have to be conceived of, in political terms, as a world state of emergency, in two senses: a state of emergency of global scope, and a world state whose constitutional order emerges from out of the sovereign decisions made therein.

After this typically Jorjanian move, we are back to the land of Prometheus and Atlas, where each chapter is a mini-seminar; Chapters Three, Four and Five are devoted to documenting this “technological singularity” that “calls into question the human form of life as we know it.”

Take biotechnology:

What is likely to emerge in an environment where neo-eugenic biotechnology is legalized but not subsidized or mandates is the transformation of accidental economic class distinctions, which is possible for enterprising individuals to transcend, into a case system based on real genetic inequality.[9] [13]

Next up, robotics, artificial intelligence, drones, and most sinister of all, virtual reality:

In some ways, the potential threat to the human form of life from Virtual Reality is both more amorphous and more profound than that posed by any other emergent technology. It could become the most addictive drug in history. The enveloping of the “real world” into the spider-web of Cyberspace could also utterly destroy privacy and personal identity, and promote a social degenerative sense of derealization.

None of this matters, however, if we cannot maintain the “development of industrial civilization” after “the imminent decline in petroleum past the global peak in oil production.” This can only be addressed by the third technological development, “a return to the Moon for the sake of Helium-3 fueled fusion power.” This will “challenge us to rethink fundamental concepts such as nationalism and international law.” Who, on the Moon, is to be sovereign?

Having softened up the reader with this barrage of terrifying facts, Jorjani is ready to spring his next trap. The task of regulating biotechnology and guiding us to the moon requires a world state; Schmitt has shown us that a state can emerge only from the ethos of a particular people.

However,

We have also seen that a bureaucratic world state will not suffice. Certain developments in robotics mean the end of personal privacy [and] as we live ever more of our lives in cyberspace, identity theft is coming to have a much more literal meaning. All in all, the convergent technological advancements that we have looked at require a maximal trust society simply for the sake of human survival. We need a world society with total interpersonal transparency, bound together by entirely sincere good will.

And yet, even if we could create such a society, perhaps by biotechnology itself, we don’t have the time: we have at most a generation to act. Is there “an already existing ethos, a living tradition that is inter-civilizational[10] [14] and global in scope,” as well as promoting high levels of mutual trust?

That would be, of course, “the common Aryan heritage of the Indo-European civilizations.”

It’s as if Jorjani took Carl Schmitt and Kevin MacDonald[11] [15] and through some kind of genetic engineering produced a hybrid offspring: the World State.

Reeling but still upright, the Alt-Right reader at least still has this to hang onto: “good old Aryan culture!” Lulled into complacency, he doesn’t even see the next punch coming:

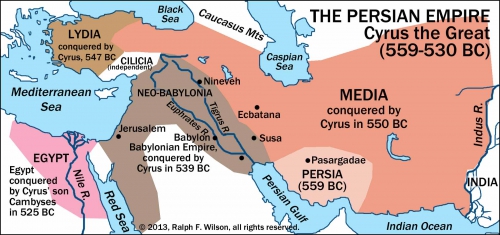

Iran or Iran-Shahr — literally the “Aryan Imperium” — is the quintessentially Indo-European Civilization.

Iran is not just one great civilization among a handful of others, it is that crossroads of the world that affords all of humanity the possibility for a dialogue toward the end of a new world order.

A renaissance of Greater Iran . . . will be the spearhead of the war for an Indo-European World Order.

Once the Iranian or Aryan Renaissance triumphs domestically, the Persians and Kurds in the vanguard of the battle against the nascent global Caliphate — with its fifth-column in the ghettos of the major European cities — will reconstitute Greater Iran as a citadel of Indo-European ideals at the heart of what is now the so-called “Islamic world” . . . this is going to happen.

At this point, the alt-Right reader throws up his hands and shouts “No mas! I didn’t sign up for this crusade!”

Now might be the point to bring up the general question: in what sense — if any – is Jorjani an Alt-Right writer? There is that resignation business, and what’s with all this Iranian Renaissance stuff?[12] [16]

Well, you say “Aryan,” he says “Iran.” The point is that the Aryan Imperium is explicitly White, and fulfills Greg Johnson’s principle of setting up a white hegemony where all public issues are discussed in term of “what’s good for the White race,” rather than other hot button issues like school choice, abortion, etc. Under Jorjani’s postulated “world emergency” the new Aryan overlords would be viewed as both necessary and, therefore, literally unquestionable.[13] [17]

In a way, the Aryan Imperium is even too white, hence the alt-Rightist’s discomfort. Jorjani delights in taking “conservative” ideas and taking them to their logical endpoint. Enumerating the accomplishments of the Indo-Iranians, he lists “major . . . religious traditions such as . . . Zoroastrianism, Hinduism, and Buddhism.” As in his previous book, Jorjani goes beyond the fashionable anti-Jihadism of the Right and locates the root of the problem in the Semitic tradition as such.

This is probably not what most alt-Rightists signed on for. But then, it is they who are among “those self-styled ‘identitarians’ who want to hold on to Traditional Christianity and hole up in one of many segregated ethno-states.” Not to worry; they will “perish together with the other untermenschen” in the coming world state of emergency, which will be the “concrete historical context for the fulfillment” of Zarathustra’s prophecy of a “new species,” the Superman.

So, I guess we have that to look forward to, at least.[14] [18]

As you can see, the anti-Christian animus can claim a pedigree back to that alt-right darling, Nietzsche, although it may not be something one is supposed to mention in public. That brings us to another sense in which Jorjani is an alt-Right thinker: he draws on, and orients himself by, the alt-Right canon: Nietzsche, Heidegger, Schmitt, de Benoist, Faye, Dugin, etc.

But again, as always . . .

“I’ve tried to clear my way with logic and superior intellect. And you’ve thrown my own words right back in my face, Brandon. You were right, too. If nothing else, a man should stand by his words. But you’ve given my words a meaning that I never dreamed of! And you’ve tried to twist them into a cold, logical excuse for your [Aryan Imperium].”[15] [19]

Calm down, people! Always with a little humor, comrades, to lighten the day’s geopolitical work.

While there is a cottage industry of goodthinkers trying to find evidence — well, more evidence — of how Heidegger’s allegiance to National Socialism “twisted” his thought, Jorjani found connections with parapsychology and even the occult; it’s a toss-up which association Heidegger epigones found more infuriating.

Now, Jorjani uptilts Heidegger’s colleague and fellow party-member Carl Schmitt; did Schmitt argue that the world-state of liberal globalist dreams was logically and existentially impossible? Sure, except this place here where he grants that one would be possible and necessary — if aliens invaded.[16] [20]

As for your White Imperium, sure, we’ll have that . . . run out of Tehran![17] [21]

The alt-Right is full of titanic thinkers of the past — Heidegger, Spengler, Yockey, Benoist — and their modern epigones (fully their equals, at least in their own minds), but Jorjani is the thinker we need now: more than just a lover of wisdom, he’s a wise guy.[18] [22]

That’s how Wolfi Landstreicher describes Max Stirner, and we might compare our situation to the Left Hegelians and Die Freien who populated the Berlin beerhalls and Weinstube — the blogs of the day — in the wake of Hegel. Among them were such “serious” thinkers as Karl Marx — and we know how that turned out — and Bruno Bauer, who invented the Christ Myth theory.

But there was also an individual — a Unique One — born Caspar Schmidt, calling himself — his online handle, if you will — “Max Stirner.”

As I wrote in my review [23] of Landstreicher’s new translation of The Unique One and Its Property, Stirner was driving people nuts right from the start.

Marx famously claimed to have found Hegel standing on his head, and to have set him right-side up; in other words, he re-inverted Hegel’s already inverted idealist dialectic and made material reality the basis of ideas.

Stirner, by contrast, picked Hegel up and held him over his head, spun him around, and then pile-drove him into the mat; a philosophical Hulk Hogan.

Stirner’s magnum opus is a kind of parody of Hegelianism, in which he spends most of his time using the famous dialectic to torment Hegel’s epigones, first Feuerbach and then, at much greater length, the Whole Sick Crew of (mid-19th century Euro-)socialism.

Have you philosophers really no clue that you have been beaten with your own weapons? Only one clue. What can your common-sense reply when I dissolve dialectically what you have merely posited dialectically? You have showed me with what kind of ‘volubility’ one can turn everything to nothing and nothing to everything, black into white and white into black. What do you have against me, when I return to you your pure art?[19] [24]

Of course, unless you’re Howard Roark claiming “no tradition stands behind me,” everyone has their sources; the more creative among us are the ones who transform them, and no one’s alchemical sleight of hand is as dramatic as Jorjani’s.[20] [25] As the great Neoplatonist John Deck wrote:

Clearly, there can be no a priori demonstration that any philosophic writer is more than a syncretist: but if it is good to keep our eyes open to spot “sources,” it is even better to bear in mind that a philosopher is one who sees things, and to be ready to appreciate it when sources are handled uniquely and, in fact, transmuted.[21] [26]

As always, the Devil — or Ahriman — is in the details.[22] [27]

In reviewing his previous book, I took Jorjani to task for assuming that a particular view of Islam, the fundamentalist, was ipso facto the “true” or “original” version of the religion.

Why privilege the fundamentalist, or literalist, view? It is as if Jorjani thinks that because religion determines culture (true) it does so in a way that would allow you to read off a culture simply from a study its sacred books, especially the ethical parts.[23] [28]

But the latter is neither the same as nor a valid inference from the former. A religion does not “imply” a culture, like a logical inference. Both the Borgia’s Florence and Calvin’s Geneva are recognizably “Christian” and totally unlike any Islamic society, but also almost totally unlike each other.

By this method, one could readily predict the non-existence of lesbian rabbis, which, in fact, seem to be everywhere.

The temptation, of course, is to dismiss those outliers are “not really Islam,” in preference to one’s own, whether one is a Wahabi oneself or an observer like Jorjani insisting Wahbism is “real” Islam; but to call the moderate Islam that made Beirut “the Islamic Riviera” heretical ironically puts Jorjani and other anti-jihadis in the same boat as an Obama, who hectors terrorists about “betraying Islam” and lectures us that “Islam is a religion of peace.”[24] [29]

And yet Jorjani himself upbraids Huntington for advising Westerners to “take pride in the uniqueness of western culture, reaffirming, preserving and protecting our values from internal decay,” which he derides as “the kind of conservatism that imagines “western values” to be static.”

In the book under review here, Jorjani doubles down: Islam is still based on a book actually written by this chap Mohammed, and a reading thereof shows it to be “impervious to reform or progressive evolution.”

But to this he now adds a similar concept of Zoroastrianism, but of course given a positive spin:

A handful of ideas or ideals integral to the structure of Iranian Civilization could serve as constitutional principles for an Indo-European world order: the reverence for Wisdom; industrious innovation; ecological cultivation, desirable dominion; chivalry and tolerance.

Jorjani writes in his two, last, geopolitical chapters as if there were a discernable set of “principles” written down or carved in stone as defining Zoroastrianism, and that these principles were adhered to, unquestionably, down through Persian history, accounting for its salient features. In reality, like all religions, Zoroastrianism was in favor and out of favor, adhered to strictly and given mere lip service, and always subject to reinterpretation and syncretism with outside sources.

After flourishing early on among the Achaemenid Persians (600s to 300s BC), Zoroastrianism was suppressed under the Parthian regime (200s BC to 200s AD), only to reemerge under the Sassanid dynasty for a few final centuries before the Arab conquest imposed Islam.

Zaehner distinguished three distinct periods in the history of pre-Islamic Zoroastrianism: “primitive Zoroastrianism,” that is, the prophet’s own message and his reformed, monotheistic creed; “Catholic Zoroastrianism,” appearing already in the Yasna Haptaŋhaiti and more clearly in the Younger Avesta, which saw other divinities readmitted in the cult, a religious trend attested in the Achaemenid period, probably already under Darius I and Xerxes I, certainly from Artaxerxes I onwards as shown by the calendar reform that he dates to about 441 BCE and finally the dualist orthodoxy of Sasanian times.[25] [30]

At times Jorjani recognizes this interplay of text, interpretation, and historical necessity, at least with Christianity:

The so-called “Germanization of Christianity” would be more accurately described as an Alanization of Christianity, since Alans formed the clerical elite of Europe as this took shape.[26] [31]

Or here:

One particularly colorful practice which reveals the love of Truth in Achaemenid society is that, according to Herodotus, the Persians would never enter into debates and discussions of serious matters unless they were drunk on wine. The decisions arrived at would later be reviewed in sobriety before being executed. . . . It seems that they believed the wine would embolden them to drop all false pretenses and get to the heart of the matter.

Indeed, and rather like the Japanese salarymen as well.[27] [32] But it comports poorly with Zoroaster’s insistence on sobriety and temperance; indeed, according to Zaehner, the whole point of Zoroaster’s reforms was the recognition that the drunken, orgiastic rites of the primitive Aryans (involving the entheogen haoma, the Hindu soma) were inappropriate for peasants in a harsh mountainous terrain.[28] [33]

I have spent this time — shall we say, deconstructing — Jorjani’s account of Zoroastrian culture because it is the envelope in which he presents us with his Indo-European principles, and is therefore important; but this must not be taken to mean I object to the principles themselves. They are fine ones, but if we choose to make them the principles for our Indo-European Imperium, it will be because we do so choose them our own, not because they instantiate some hypothetical, synchronic version of Zoroastrianism which we have already persuaded ourselves must govern our choices.[29] [34]

Such great, world-creating choices require the guidance of great minds, and not just those of the past. The Great Thinkers of the past are not only Titans but dinosaurs; and racing around them is a wily newcomer, Jason Jorjani — a prophet, like Nietzsche or Lawrence, who imagines new forms of life rather than reiterating the old ones[30] [35] — to whom the archeo-future belongs.

Notes

[1] [36] The Manchurian Candidate (Frankenheimer, 1962)

[2] [37] Surprisingly, this myth is confirmed: MythBusters Episode 214: Bullet Baloney [38] (February 22, 2014).

[3] [39] Big scope and small scope, as we used to make the distinction back in the analytic philosophy seminars. Down the hall in the English Department corridor, Joyce Carol Oates was typing away at her novel of madness in Grosse Pointe, Expensive People: “I was a child murderer. I don’t mean child-murderer, though that’s an idea. I mean child murderer, that is, a murderer who happens to be a child, or a child who happens to be a murderer. You can take your choice. When Aristotle notes that man is a rational animal one strains forward, cupping his ear, to hear which of those words is emphasized — rational animal, rational animal? Which am I? Child murderer, child murderer? . . . You would be surprised, normal as you are, to learn how many years, how many months, and how many awful minutes it has taken me just to type that first line, which you read in less than a second: I was a child murderer.” (Vanguard Press, 1968; Modern Library, 2006).

[4] [40] “My Resignation from the alt-Right,” August 15th, 2017, here [41].

[5] [42] It’s happening here as well; a commenter at Unz.com observes that [43] “That’s the thing about representative democracy with universal, birthright citizenship suffrage. You don’t need to invade to change it, just come over illegally and have children. They’ll vote their homeland and culture here.”

[6] [44] Jorjnan’s paraphrase of Schmitt’s The Concept of the Political, p. 54: “Humanity as such cannot wage war because it has no enemy, at least on this planet.

[7] [45] In Prometheus and Atlas, Jorjani discusses an imaginal exercise conducted by Heidegger himself in his Zollikon Seminars, in which participants are asked to “make present” the Zurich central train station. Heidegger insists that “such ‘making present’ directs them towards the train station itself, not towards a picture or representation of it,” his conclusion being that ‘We are, in a real sense, at the train station.” (Quoting from Zollikon Seminars: Protocols, Conversations, Letters [Northwestern, 2001], p. 70). See my review [8] for a discussion of the implications of the Japanese saying, “A man is whatever room he is in.”

[8] [46] In a late work, Theory of the Partisan, Schmitt already begins to suggest that the development of what we would now call “weapons of mass destruction” may already constitute such a planetary threat.

[9] [47] Perhaps only evaded by “a small but highly motivated and potentially wealthy anarchical elite of Transhumanists who want to push the boundaries ad infinitum.”

[10] [48] I think Jorjani reverses “civilization” and “culture” (i.e., ethos) as defined by “Quintillian” here [49] recently: “The left cunningly advances its false narrative by deliberately contributing to the confusion between two terms: culture and civilization. Simply put, a civilization is an overarching (continental) commonality of shared genetics, religious beliefs, and political, artistic, and linguistic characteristics. A civilization is generally racially identifiable: African civilization, Asian civilization, and white European civilization. A civilization can have any number of constituent cultures. The culture of the Danes and that of the Poles are very different in superficial details, but they are both immediately identifiable as belonging to the same Western civilization. Africans are similarly divided among a variety of culture and ethnicities.” But “As I [Jorjani] understand it, a civilization is a super-culture that demonstrates both an internal differentiation and an organic unity of multiple cultures around an ethno-linguistic core.” Both would agree, however, that “the Indo-Europeans originated nearly all of the exact sciences and the technological innovations based on them, the rich artistic and literary traditions of Europe, Persia and India, as well as major philosophical schools of thought and religious traditions.” (Jorjani)

[11] [50] See, for example, the discussion of trust in White societies in Greg Johnson’s interview with Kevin MacDonald, here [51].

[12] [52] Not that there’s anything wrong with that.

[13] [53] A typically subtle point: by requiring a high-trust population, Jorjani implicitly excludes Jews and other Semites. A low-trust people themselves, the Jewish plan for World Order is to encourage strife within and between societies, until the sort of managerial or administrative state Jorjani rejects is installed to maintain order, under the wise leadership of the secular rabbis.

[14] [54] “So we finish the eighteenth and he’s gonna stiff me. And I say, “Hey, Lama, hey, how about a little something, you know, for the effort, you know.” And he says, “Oh, uh, there won’t be any money, but when you die, on your deathbed, you will receive total consciousness.” So I got that goin’ for me, which is nice.” Bill Murray, Caddyshack (Landis, 1980).

[15] [55] Rupert Cadell, upbraiding the crap-Nietzscheanism of his former pupils in Rope (Hitchcock, 1948). Cadell, of course, actually refers to “your ugly murder” which, the viewer knows, sets off the action of the film.

[16] [56] A not uncommon trope in science fiction, from The Day the Earth Stood Still to Childhood’s End to Independence Day; as well as a particularly desperate kind of Keynesian economic punditry: in a 2011 CNN interview video Paul Krugman proposed Space Aliens as the solution to the economic slump (see the whole clip here [57] for the full flavor).

[17] [58] I am reminded of the moment when Ahab reveals his hidden weapon against the Great White Whale: “Fedallah is the harpooner on Ahab’s boat. He is of Indian Zoroastrian (“Parsi”) descent. He is described as having lived in China. At the time when the Pequod sets sail, Fedallah is hidden on board, and he later emerges with Ahab’s boat’s crew. Fedallah is referred to in the text as Ahab’s “Dark Shadow.” Ishmael calls him a “fire worshipper,” and the crew speculates that he is a devil in man’s disguise. He is the source of a variety of prophecies regarding Ahab and his hunt for Moby Dick.” (Wikipedia [59]) For more on Moby Dick and devils, see my review of Prometheus and Atlas.

[18] [60] “You know, we always called each other goodfellas. Like you said to, uh, somebody, “You’re gonna like this guy. He’s all right. He’s a good fella. He’s one of us.” You understand? We were goodfellas. Wiseguys.” Goodfellas (Scorsese, 1990). Who but Jorjani would define “arya” as “‘crafty,’ and only derivatively ‘noble’ for this reason.” But then is that not precisely the Aryan culture-hero Odysseus?

[19] [61] Max Stirner, “The Philosophical Reactionaries: The Modern Sophists by Kuno Fischer,” reprinted in Newman, Saul (ed.), Max Stirner (Critical Explorations in Contemporary Political Thought), (Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), p. 99.

[20] [62] Given Jorjani’s love of Heraclitus, one thinks of Water Pater’s description, in Marius the Epicurean, of the Roman philosopher Aristippus of Cyrene, in whom Heraclitus’ “abstract doctrine, originally somewhat acrid, had fallen upon a rich and genial nature well fitted to transform it into a theory of practice of considerable simulative power toward a fair Life.”

[21] [63] John N. Deck, Nature, Contemplation, and the One: A Study in the Philosophy of Plotinus (University of Toronto Press, 1969; Toronto Heritage series, 2017 [Kindle iOS version].

[22] [64] Including such WTF moments as Jorjani off-handedly defines “Continental Philosophy” as “largely a French reception of Heidegger.”

[23] [65] Ethical treatises, such as Leviticus, as best seen as reactions to the perceived contamination of foreign elements, rather than practical guides to conduct; Zaehner dismisses the Zoroastrian Vendidad as a list of “impossible punishments for ludicrous crimes. . . . If it had ever been put into practice, [it] would have tried the patience of even the most credulous.” R. C. Zaehner, The Dawn and Twilight of Zoroastrianism, London, 1961, pp. 27, 171.

[24] [66] As one critic riposted, “Who made Obama the Pope of Islam?” Indeed, the Roman Catholic model may be the (mis-)leading model here; Islam, like Judaism, lacks any authoritative “magisterium” (from the Greek meaning “to choose”) to issue dogma and hunt down heretics. Individual imams have only their own personal charisma and scholarly chops to assert themselves, just as individual synagogues hire and fire their own rabbis, like plumbers. On Jorjani’s model, lesbian rabbis should be as scarce as unicorns, rather than being a fashionable adornment of progressive congregations.

[25] [67] Encyclopedia Iranica Online, here [68]. Quoting Zaehner, op. cit., pp. 97–153.

[26] [69] Compare, on your alt-Right bookshelf, James C. Russell: The Germanization of Early Medieval Christianity: A Sociohistorical Approach to Religious Transformation (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994).

[27] [70] What, by the way, happened to Japan, which in Jorjani’s first book was specially favored by its non-Abrahamic traditions and catastrophic encounter with atomic energy to lead the way into the new future?

[28] [71] Zaehner, op. cit., p. 81. In fact, Herodotus never mentions Zoroaster at all, suggesting how obscure and un-influential the cult was at that time. Rather than the modern idea of “in vino veritas,” the “wine” here, as in the symposiums of Greece, may have been “mixed wine” containing entheogenic substances. “Visionary plants are found at the heart of all Hellenistic-era religions, including Jewish and Christian, as well as in all ‘mixed wine’, and are phenomenologically described in the Bible and related writings and art.” (Michael Hoffman, “The Entheogen Theory of Religion and Ego Death,” in Salvia Divinorum, 2006.)

[29] [72] Whether it’s Cyrus or Constantine, periods of Imperium are ipso facto periods of syncretism not orthodoxy. Surely this is more in accord with the author’s notion, here and elsewhere, of truth emerging from a Heraclitean struggle?

[30] [73] “[Henry] James evidently felt confident that he could make his last fictions not as a moralist but as a prophet; or a moralist in the sense in which Nietzsche and Lawrence were prophets: imagining new forms of life rather than reinforcing old ones.” Denis Donoghue, “Introduction” to The Golden Bowl (Everyman’s Library, 1992).

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg