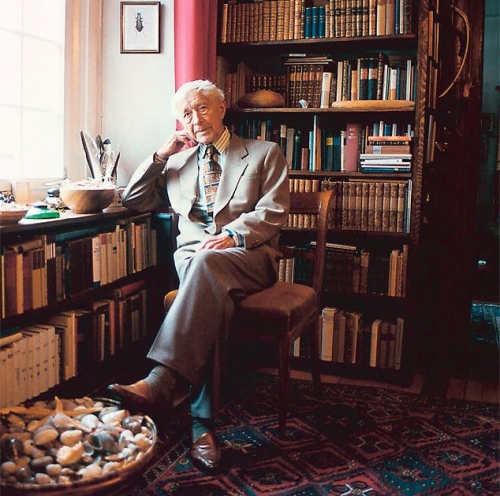

Martin Heidegger, Oswald Spengler – “Martin Spengler” – these two 20th-century thinkers provide the main source of inspiration behind this project. Both sought to understand the times we live in, and to bring into view the deeper historical and philosophical significance underlying many of the political, economic, social, and cultural issues before us today. Both offer profound insight, and our goal here will be to lean on them in order to tease out what is at stake in many of the day to day problems, challenges, and controversies that grip our attention across the Western world.

Spengler’s masterpiece is his Decline of the West, which first appeared in Germany in the years immediately following World War One. His contribution is to set contemporary events within a civilizational context, as milestones in the development of a culture whose evolution has been dictated by its own internal laws and dynamics, apparent at its very birth 1,000 years ago. Spengler allows us to see how the impulse that drove Medieval European craftsmen to construct magnificent Gothic cathedrals that soared towards the heavens, while betraying ever more intricate detail in their stonework, is the same motivating force behind the transgenderism agenda today, Hollywood’s obsession with the Superhero genre, and in the attractive power of the dream to travel in space.

For Heidegger the key event has been the rise of Modern science and technology, and it is the implications of this development he seeks to reveal. It is Heidegger who helps us to understand how the Modern project is in its essence nihilistic; if followed through to its logical conclusion it means no less than the annihilation of both the world and humanity. This is a cataclysmic perspective, but Heidegger’s reasons for sounding the alarm apply with a monumentally increased force since he first raised this prospect during the 1930s. It was Heidegger who understood that the “subjectivism” which reduces the world to a “standing reserve,” a resource to be used at our convenience, is at its core empty, that the desire for comfort and ease is in fact a death wish. Nietzsche understood this too. The danger does not lie so much in an ecological disaster, the consequence of reckless actions such as the use of GMO crops, but from the success of technology rather than its failure. We can see this with “climate change,” first global warming will be successfully held at bay, then extreme weather events prevented, and then . . . the outside world will be made to look and feel no different from the carefully controlled environment we have inside every shopping mall. After all, if you could push a button from your beachside mansion to stop an oncoming hurricane in its tracks, and instead select for a pleasant view offshore, why wouldn’t you?

No one openly articulates such an agenda, and it does not matter whether it is realistic or complete fantasy, the logic is there nonetheless. It has been present for a thousand years, and it is immensely powerful. Our entire civilization is testimony to its power. This is the value both Heidegger and Spengler bring to a discussion of such issues, they allow us to approach topical subjects such as climate change or transgenderism from a very different angle, to understand why these are the battlegrounds today, and what is at stake.

A third dimension, however, is also needed. It is one neither “Martin” nor “Spengler” were aware of in their lifetime, nor is it a question that has ever concerned Western philosophy to any significant extent in its 2,500-year history. It is a product of our time, and as such is the key to understanding everything. In this respect, “the West” is unique, and at its heart lies a contradiction.

Civilisation by its nature is a masculine project, but Western civilization is in its essence – feminine.

The driving purpose behind the science and technology of the West is to make life easy, comfortable, safe, and amusing. These are feminine desires not masculine ones. Western men have striven for centuries to deliver such a lifestyle to their women, and over the last 70 years or so this effort has borne fruit in the unsurpassed standard of living enjoyed by large sections of the population in Western countries. But the more it has done so, the more the essentially feminine character of the West has come into play. Masculine values, masculinity, men, these were all necessary to bring us to this point, the achievements of science and technology are products of the masculine impulse to make an impact on the world, to understand it, shape it, to create with it, to build with it, for their enjoyment in part but most of all for their women and children, and for the sake of the larger civilizational project to whose success they are committed. But to the extent this project is realized, and life does become easy, comfortable, safe, and amusing, masculinity becomes increasingly redundant, and fades into the background. In its place the feminine becomes primary, a process that has accelerated to an enormous extent over the past half-century with the arrival of the “sexual revolution” in the 1960s.

In the world that is emerging, there are no limits, nothing that women cannot do, nor anything that requires the masculine impetus to turn outwards towards the wider world, to discover its secrets, confront its dangers, for there is no longer is an outside world. Once we reach the point where everything that exists is either an oversized shopping mall, an air-conditioned office building, a campus safe space, a theme park, or a McMansion, masculinity has served its purpose and has no further place, other than to supply routine maintenance services in the background. In this world everything is self-referential, reality is what we make it, truth is what we decide it to be, on the basis of what makes us feel comfortable, safe, and amused. This is why the internet and social media are so central to our culture, why reality TV is our iconic genre, celebrities our key figures, entertainment our main industry, marketing our critical skill set, and brand value our ultimate asset. It is also why #fakenews is a thing.

This self-referentiality is Heidegger’s “subjectivism.” It is extending its influence everywhere, even such former bastions of masculinity as the military. Western militaries are completely feminized, with the partial exception of Special Forces, the only units who actually experience real combat. This is not to say that US or NATO forces do not kill and destroy, they do on a massive scale, their mostly male members also die, but they do not fight, they do not even engage their “enemy.” Instead they conduct operations against fictitious opponents who are figments of their own imagination, and take casualties at the hands of real adversaries about who they know nothing. The disastrous British campaign in Helmand, Afghanistan, from 2006-10 is the classic example of this, launched against an insurgent force that did not exist at that time, but which soon did come into being with a vengeance as a result of the “counter-insurgency” operation.

Helmand is the rule rather than the exception. It is no accident that the weakest branch of the US military machine has always been Intelligence, because this is the one element that cannot be self-referential if it is to be effective.

The Eclipse of Truth

We see the contradiction that runs through the West above all in the current state of science as an institution. In spite of its critical role in the Western civilizational project, science today is in an appalling state of disrepair. This is so even though vast amounts of data and new information are becoming available to many scientific disciplines due to earlier developments in technology, and also to the enormous resources being thrown into research and academia. Astronomy is a good example of this. However, the ability to intellectually process these sources into theoretical advances, to improve our understanding, has been all but lost, at least in the mainstream. Instead, astronomically related areas such as cosmology and astrophysics have disappeared into a fantastical set of rabbit holes that bear no relation to any reality outside of their own mathematical set of fictions. As a result they are completely sterile, there has been no progress in these branches of science for decades, in sharp contrast to the revolutionary breakthroughs that marked the first half of the 20th century. These gave us the technological advances that make the present possible, although the irony lies in that they also have contributed in large part to the dead end we now find ourselves in. This includes its poster boy Albert Einstein, who in spite of his personal integrity has been the single greatest catastrophe ever inflicted on the scientific enterprise. It is no accident that this individual was the first ever science “celebrity,” in no other period could a set of intellectually incoherent nonsense be mistaken for genius, but then again, it did so because it suited certain purposes . . . long before #fakenews came #fakescience.

The reason for this is the eclipse of truth, which is a masculine value, as the determining factor in decisions over what ideas to accept, papers to publish, research to fund, who to appoint, and who is selected to go viral, at least on the media circuit. Science as a practice has to balance its inquiry into the world as it really is with a whole series of competing interests. These might be commercial, political, ideological, institutional, or personal. The more important a branch of science is to Western society as a whole, the more corrosive these other influences, so that when we get to a central political issue such as “climate change,” we soon find that the quality of the science being produced on this question is utterly corrupted, and from a scientific standpoint completely worthless. This is because its purpose is not to find the truth, but to support an agenda, which it does by creating “models” of how the world should be and then using these to justify policy decisions whose motivation always lay elsewhere – self-referentiality once again. The reality is that climate “science” is not science at all, which goes to explain why its proponents refuse to honor any of the principles that guide genuine scientific inquiry – honest debate, transparency of data, willingness to admit uncomfortable facts, or explore alternative hypotheses.

An indication of the West’s true character and current state of decay can be seen in some of the intractable problems that plague modern society. Many of these revolve around health, arguably the area that provides the greatest source of pride to those who believe in the achievements of Western civilization. But while it is true that life expectancy is at record levels, infant mortality at its lowest, and that a cut finger is unlikely to result in death from a ravaging infection, it can hardly be argued that the population of a nation such as the United States is “healthy” in any meaningful sense. If we look at the obesity epidemic, for example, what is most significant about this problem is less that people are getting fat, but that Western medicine has proved totally incapable of making even a small dent in the constantly rising numbers of the obese. A different approach is clearly needed, but one will only be found on the basis of civilizational values that understand medical treatment in terms that do not involve drugs or surgery. Counter currents of this nature do exist, such as the ancestral health movement, or the advocates of LCHF, but these are defined precisely by their rejection of the Western project and its conception of what a healthy way of life is. The same applies to mental health issues, or the unbelievably high rates of addiction across the West, to everything from pain killers, shopping, gambling, gaming, porn, anything that offers an escape from an otherwise entirely meaningless, but materially quite comfortable, existence.

The Desire to Escape

It is Spengler who shows us that this desire to “escape,” in his words towards “the infinite,” was present at the very birth of the West, and is in fact its driving force. This too needs to be understood in terms of masculinity and femininity. The masculine impulse is not to escape the world but to go out and engage with it, to learn how to navigate through it, to understand it, and with this knowledge to create and to build with it. A man may seek an escape from the wind and the rain for his family, but the shelters he constructs are made from real materials, and if they are not built according to the natural laws that govern civil engineering they will fall down. This is why truth is the paramount masculine value, and this truth is never self-referential, it is truth about the external world, so that humanity can live within this world.

The feminine impulse is the opposite, it is an attractive force and its ultimate point of reference is the woman herself and her children. If the masculine seeks to expand outwards towards the infinitely large, to ever extend knowledge and understanding, then the feminine measures this in terms of what it means to her, how it affects her, whether she likes what emerges around her as a result of this, or not. Men build houses, but women decide whether they want to live in these structures, and turn them into homes. The feminine is in its essence aesthetic, its measure is beauty, and the beautiful is appreciated through emotion, how it makes her feel.

During the rise of the West, this masculine impulse is harnessed and the Modern world takes shape over time. The feminine character of the Western project, however, is expressed in the ultimate end state Western civilization sets as its objective. This is Spengler’s “infinity,” but in everyday terms it goes under the slogan of “freedom.” The dominant motive behind the entire development of the West has been the desire to be free, and this means freedom from any and all constraints. Science and technology emerge as the means by which to escape the constraints of nature, but alongside this there is also the desire to escape social constraints. During the first centuries of the West, this mostly involved the struggle to overcome the Catholic Church, which dominated the social and cultural landscape of medieval Europe, and this lead to the Protestant Reformation. Later it becomes the desire to be free of any religious imposition on life whatsoever, whether through moral codes or the law of the land. Western society becomes secular.

Freedom is a feminine value, not a masculine one. Femininity resents any external constraints on it, whether natural or social, because its reference point is the woman herself, in her singularity. There is no such thing as a feminine morality, because even two women form a set of entirely different compass points for any moral code. These might coincide, the two might agree and cooperate well together, but they also might not, there is no force behind the agreement, as soon as it feels like a constraint to either of them it will be abandoned. Women approach all relationships in this way, except with their children, there the rules change.

Masculinity does not strive for freedom, it seeks to serve. A man is measured by his contribution to something larger and outside of himself, his family, his tribe, his nation, his civilisation, its Gods, the truth. This service must be voluntary, and it must be valued. The Roman slave in revolt may kill his master but he will also willingly give up his life in the army of Spartacus, and ask only that in battle his general not throw this away cheaply.

For the same reason, equality is not a masculine value either. Men contribute to the best of their ability, because that is the source of their worth, but the end results are measured externally. The input is irrelevant, only the output. Masculinity naturally gravitates towards hierarchy, because some are more talented, experienced, or able than others, and what matters is the common venture, success or failure, victory or defeat. Men will accept the leadership, and even the domination of others, if this leads to a good outcome, because that is all that counts. Better to follow the victorious general, than lead an army to its destruction.

The feminine, on the other hand, does aspire to equality, because like freedom it is an abstract concept, it means the removal of any expectations placed upon her by anyone, which she might perceive as a constraint. Equality is the stepping stone towards freedom, which is the ability of a woman to act as her own point of reference in any aspect of her life. Today this goes under the term, “empowerment,” or “You go girl!” This is one form of the “tendency towards abstraction” we will try to elaborate on further.

Masculinity, however, acts as a counter-balance to this female “solipsism.” The masculine overrides this impulse and it is the woman who benefits, because it allows her to serve something greater – children, to become something larger than herself, to contribute, to leave her mark on the earth, to attain a slice of immortality. Men do this by imposing an order that serves the civilizational project they are committed to, in other words they impose social constraints on women. This is the “patriarchy,” it ensures that a society will continue because there will be future generations, that women will bear children. It is a civilizational project that makes women have babies, and this is its greatest gift to femininity, to those same women, it overcomes their own drive to “self-referentiality” and allows them to be something more, to participate in something larger.

The project of Western civilization, on the other hand, has been to escape this very civilizational constraint. By the 1960s it had achieved an important milestone along this path through the application of science and technology, with the invention of the contraceptive pill. As a result, birth rates have plummeted, well below the numbers required to reproduce the population. This is one reason why it is safe to predict the coming demise of the West, a social order can not survive if its women do not have children.

Transhumanism — The Final Showdown

The West, in its essence, is neither a human nor a natural society. The current debate – is gender real ? – is not directed at finding truth but is instead a program of action – “we will make it so that there is no such thing as gender.” Masculinity and femininity, their polarity, will be abolished. This process is already well advanced, especially in the urban centers, and can be objectively measured by tracing the plummeting levels of testosterone in Western men. It is also the meaning behind the pronoun controversy that catapulted Jordan Peterson into the spotlight during 2015, and why his stance is so important.

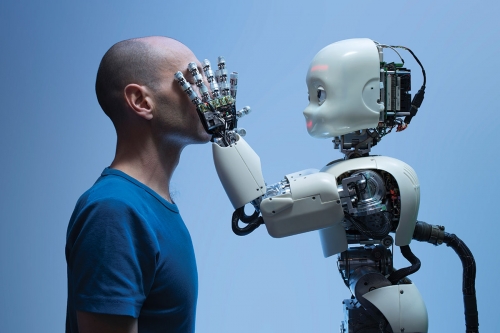

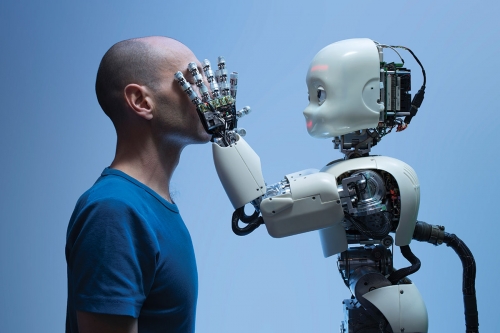

Transgenderism is only the prelude, the real showdown is still to come. This will go under the title, “transhumanism,” and if its proponents are successful it will mean the end. Humanity will cease to exist. The technology is not yet fully developed, but the work is being undertaken, and rapid progress is being made. Starting with heart implants, prosthetic limbs, and wearable tech, the ultimate goal will be to overcome the limitations of the human body and achieve immortality. This will be done through packages whose benefits are undeniable – the replacement of legs lost by soldiers to IEDs, the extension of life expectancy, early detection of disease onset, and for this reason will be hard to resist.

An idea of what this means for humankind can be seen in the stresses and strains already affecting peak human activity, the Olympic Games. On the one side, the dissolution of gender difference will destroy women’s sport, a foretaste of which can be seen in the controversy surrounding South African runner Caster Semenya. On the other, advances in prosthetics mean Paralympians will increasingly overtake “able-bodied” athletes in their achievements, this already being the case for the 1500m event. In the background lies the ever more murky divide between legitimate diet and nutrition supplementation, and performance enhancing drugs, an indeterminancy that is also being exploited for political ends, as in the blatantly unjust treatment of Maria Shaparova over her use of meldonium. The point here is that the ruling to outlaw this drug in 2015, after years of its legally sanctioned use, was entirely arbitrary. The same applies to the earlier ban on blood doping.

All these trends lead in the same direction, a loss of meaning to the entire enterprise of elite sport as a human activity. This is nihilism playing itself out; it is Nietzsche’s “devaluation of all values.” The Paralympics for example, whose entire purpose is a celebration of the human spirit in the face of adversity, loses any sense of this once artificial limbs become a source of advantage rather than disadvantage, and replacing body parts becomes a desirable option. We approach the point in the first Robocop film where the decision is taken, “lose the arm,” even though it is undamaged. This has already happened on a small scale, with Australian Football League player Daniel Chick choosing to amputate an injured finger because it was harming his performance on field.

At the time, the idea of removing a body part for the sake of a sport was shocking. But the reasoning is clear, after all, what is there in our society that is not a game of some kind of other ? What better use could he have for his finger other than play a game in which he had attained a high level of mastery and was being well rewarded for doing so. Here it is important to understand what games are, and how they are essentially feminine in nature. This is because they are self-referential, defined by rules of their own making, and pursued for their own purpose – for fun. The value of a game is measured by whether it is enjoyable to play, or in our time, to watch. This applies with equal force to games that make a concession to masculinity – Call of Duty – and are therefore fun for boys to play. Such games are not masculine at all, in spite of feminist protests to the contrary, precisely because they are games – nothing is at stake. They are the safe forms of play a protective mother is happy to let her boys engage in, but they are forms that will also never allow these boys to grow into men, because for men failure has to matter, it has to hurt, physically not emotionally, it has to leave scars, it has to shape future behavior, it has to teach, the hard way. This still happens at the elite level, but only so the rest of us can spectate from the comfort of our sofas.

This helps us understand why, once a society becomes feminine primary, as the West is, it also takes on a more and more childish character. If everything is a game, with well-defined rules to prevent anyone from being harmed, and whose sole purpose is to be fun, then it is entirely legitimate to cry “not fair” whenever someone or something interrupts the proceedings. This was Donald Trump’s greatest sin, he spoiled Hillary’s party, he didn’t play by the rules, he didn’t accept that the 2016 election was never supposed to be a contest, but a game with only one outcome. This is how girls like to play, it was a crowning ceremony not a fight, and then that nasty boy ruined it. The massive display of infantilism that followed her defeat, the historically unprecedented tantrum that ensued, reflects just how far this process has gone.

This is again why Spengler and Heidegger are so useful. By standing back and adopting a perspective that spans 500 or a 1,000 years, it is possible to see how all these various strands interweave and form part of the same picture. There is a logic to this madness.

The Masculine-Feminine Polarity: The Key Battleground

It also helps us to understand what it is that needs to be defended, if all is not to be lost. First and foremost, it is this – masculine-feminine polarity.

Masculinity and femininity are opposite impulses, but not only do they complement one another, they are mutually dependent on each other if either is to fulfill its true nature. Masculine without feminine can no more be itself than feminine can be so without the masculine. This is why our current feminine primary world is so at risk of annihilation; it has lost the counter-balance it requires to avoid oblivion. Femininity alone is a black hole, it is an attractive force that has no limit, and as such will consume everything, including itself. Masculinity left to its own devices would be no different, exploding outwards into nothingness, just as the Mongol horde was able to roam the known world and conquer vast expanses of territory, but whose heartland was left a depopulated desert as a result, much as was Alexander’s Macedonia at the height of his empire.

Both Alexander and the Mongols were conquerors, but they were not builders. In their modes of warfare lay truth, they were victorious in battle, but they left nothing of beauty. They did not create a space for the feminine, no architecture to admire, no style to imitate, no structures to dwell in. As a result, they came and went, in a very short span of time, and they did so because they lacked internal cohesion, their territories were broken up from within, not without.

These were masculine primary civilizations, in which one polarity is taken to such an extreme that the absence of its opposite became its downfall. A feminine primary society works in a different way, in that what it does is undermine polarity itself. This is because the feminine impulse is singular, solipsistic, so that anything external that has shape or definition is experienced as a constraint, and as such must be neutralized or eliminated. Gender roles are by definition oppressive, not because they disadvantage women, but because they are defined, and as such are limiting, only non-gendered, abstract beings can be truly free.

This is the “tendency towards abstraction.” It is being applied to human bodily constraints, to social, ethical, and moral codes of conduct, and also to time and space. This goes under the name of “globalization.”

Globalization: The Loss of Any Meaning for Time and Place

Once again Heidegger assists us to understand what globalism is, in its essence. He does so in his classic work, “On the Question of Technology.” Here he takes the river Rhine as an example, whose role and function in modern Germany is primarily to serve as a source of hydroelectric power. This statement is usually interpreted as a kind of pro-environment stance, that the earth should not simply be seen as a set of resources for human beings to exploit. Heidegger certainly did believe that, but it is not the main point he wants to make. We see this when he introduces Holderlin’s 1808 poem, “Der Rhein,” into the discussion. For Heidegger, this poem represents the possibility of history, in which a people can emerge, a specific point in time that is their moment, and in a place that is their’s too. “Der Rhein” is not only a poetic work, it is the river, except that in the hands of Holderlin it becomes more than a moving body of water, but a historical location, the site of “Germanien,” the people whose language the poem is written in, the people for who this river is “Der Rhein.”

It is this kind of possibility the river as hydroelectricity denies. The current it produces is distributed through a grid. It is made available to anyone, anywhere, at any time. Who they are, and what they do with it, is irrelevant, in fact through the network the precise power source for any single wall socket might be any river, or any one of the various types of generating plant. This means that whatever people manage to create or achieve thanks to the availability of this electricity, it cannot bear the same relationship to the river Rhine we find in Holderlin’s poem. The connection has been severed, even if what comes into being is an online community of “Rhine lovers,” arrangements for a tourist cruise along its course, or a Heidegger fan page on Facebook. All of these can be enjoyable activities for those who participate, they can take on great significance in their personal life stories, but they do not have the capacity to be moments in historical time, where a “Germanien” is founded. There is no longer any possibility of history being made, of a “Der Rhein” coming into being.

This is globalization. It is the rupture of any meaningful link between place, time, and people. This is the postmodernist “end of the grand narrative,” which creates a lived experience of complete disorientation and disconnection, it is why our reality always feels so “artificial.” The problem is not so much that everywhere becomes the same, although this tendency is also present, but in the fact that any differences that do exist between locations are entirely random and meaningless. Even if a particular site has historical merit, or architectural splendor, this is now preserved purely for the benefit of tourists, who are visitors from nowhere in particular, who have come solely in order to be entertained, and whose value is entirely abstract – the money they spend. The great pyramids of Egypt may be the country’s main source of foreign currency earnings, but they bear no more relationship to the present nation’s culture, religion, language, or way of life, than they do to those who flock to see them. This is one reason why genuine study of these monuments has been effectively shut down for decades, in case any new understanding emerges that might have a negative impact on the tourism industry.

It is also why we can travel to Victoria in Australia and stumble across a large scale copy of the Sphinx, at what turns out to be a suburban gambling venue. Why a Sphinx? Who knows? Who cares? We can imagine future generations of archaeologists attempting in vain to decipher its meaning, because there is none, no greater relevance to the former manufacturing center and woolen industry export hub of Geelong than the original does to present day Cairo. Instead, the inspiration for this choice of design is more likely to have come from Las Vegas, where such total disregard for history and geography is taken to its logical extreme.

Las Vegas provides a good example of the “tendency towards abstraction” at work. The city’s location was chosen precisely because it was in the middle of nowhere, inside a state without any legal restrictions on gambling. Its founding was enabled by the availability of technology that overcame the natural constraints presented by the desert. Its central economic activity consists solely in the manipulation of symbolic values, games, whose appeal lies in their entertainment value. These games require as little skill acquisition as possible, and are governed purely by luck. Physical input is kept to an absolute minimum, no more demanding than pushing a button, the environment is carefully controlled for comfort, safety, and security, and no concession to time is made – venues are open 24/7 and no indication of whether it is day or night permitted. The entire enterprise is either entirely abstract or seeking to become so. Casinos, however, are not the final word in this process, their main competition now coming from the online gambling industry.

We see a similar tendency across the economy, which takes on an ever more “immaterial” character. This has two major forms. The first consists purely of symbols, above all banking and finance, which generate capital flows in various directions, but also the world of information technology that provides the platform for this kind of activity. These bear some relation to the “real” economy of tangible goods and services, but as the global financial crisis showed, this link is tenuous at best, and at times is broken entirely. The second is made up of “cultural” production – entertainment, fashion, style, brand identity, academic research, social media content, also dependent on IT to a large extent. As with finance capital, this constantly strives for autonomy from outside “reality,” it seeks to become self-referential, and in this it is becoming increasingly successful.

The Impossibility of Beauty without Truth and Truth without Beauty

This is why a defense of male-female polarity is so important. Without this, both truth, the masculine value, and beauty, the feminine value, collapse. We see this in the Geelong Sphinx, which has neither truth nor beauty – it is tacky and looks ridiculous. We also see it in trends such as the “fat acceptance movement,” whose express purpose is to separate truth from beauty by denying that there is any such thing as a naturally beautiful female human form. On this question Gad Sa’ad has provided an overwhelming mass of evidence, but his argument only stands if we hold truth to be a value, and in a feminine primary world this is simply not the case. This is because the entire objective is to escape the truth, it is to create a world free of such constraints, so that any female, no matter how morbidly obese, can be considered beautiful. It is not a matter for debate, it is an agenda to be realized, and once again it is making rapid progress, as can be seen in the overwhelming number of Western women who are seriously overweight.

Beauty requires truth, it needs to be real in order to be truly beautiful. At the same time, truth needs beauty, because reality can be ugly too. There is a truth to female genital mutilation – by making sexual intercourse a painful act it serves as a powerful reinforcer in a patriarchal order whose goal is to subordinate women’s sexuality to family and property interests. As such, female genital mutilation works. Male genital mutilation, which is much more widespread in the West than female, also achieves its original purpose, almost identical to FGM, by reducing men’s enjoyment of sex. These truths do not make either practice any the less cruel or barbaric.

The masculine-feminine polarity is the central battleground today. It is why feminist ideology is the main opponent, because this is where the insurgent forces of annihilation are currently deriving their inspiration. What is at stake here is not simply an assertion of masculinity, or men’s rights, although our society is increasingly hostile to men; it is also a defense of femininity, because there is no single force on the planet more misogynistic than feminism, especially its radical wing, which detests everything feminine with the utmost venom.

In order to combat this misogyny and androgyny, it is necessary to set it in its proper historical perspective, to understand its source, and to appreciate the critical roles played by the concepts of “freedom” and “equality.” This is not to promote “unfreedom” or “inequality,” especially in relations between the sexes, but to grasp that the masculine and the feminine are forces that run in opposite directions, have different values at their core, but who ultimate complement and are necessary for one another to flourish. It is to protect a world in which truth and beauty both have a place, and it is to preserve the possibility of a new civilizational project, or projects, arising to replace a West now well into its terminal phase of decline.

Il primo di questi è per l’appunto, il non saper leggere i segni, perché in fondo ad essi non crediamo affatto. Invero, ogni cosa nell’Universo Creato è segno, o per meglio dire, simbolo, di qualcos’altro. Questa è certezza di ogni Sapienza Tradizionale, anche e soprattutto di quella cristiana. La Storia, d’altro canto non è semplice successione di eventi, bensì Storia Sacra che si svolge dall’alfa all’omega secondo un superiore disegno di Provvidenza. Pertanto all’uomo il cui intelletto non è ancora stato sigillato non possono sfuggire i segni che continuamente essa ci presenta. Solo un’opera di cultura può colmare tale ignoranza e portare ad un primo risveglio dei sensi interiori.

Il primo di questi è per l’appunto, il non saper leggere i segni, perché in fondo ad essi non crediamo affatto. Invero, ogni cosa nell’Universo Creato è segno, o per meglio dire, simbolo, di qualcos’altro. Questa è certezza di ogni Sapienza Tradizionale, anche e soprattutto di quella cristiana. La Storia, d’altro canto non è semplice successione di eventi, bensì Storia Sacra che si svolge dall’alfa all’omega secondo un superiore disegno di Provvidenza. Pertanto all’uomo il cui intelletto non è ancora stato sigillato non possono sfuggire i segni che continuamente essa ci presenta. Solo un’opera di cultura può colmare tale ignoranza e portare ad un primo risveglio dei sensi interiori.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Se ci fermiamo un attimo a riflettere su quale sia il gesto che, durante una nostra comune giornata, ripetiamo il maggior numero di volte, riconosceremo presto che si tratta del gesto di guardare l’orologio. Un gesto così scontato, ormai istintivo, che quasi come una funzione fisiologica accompagna la nostra esistenza, che ci appare impossibile immaginare una vita senza orologio. Il tempo, pensiamo giustamente, è il giudice supremo ed impietoso della nostra vita: come potremmo vivere senza misurarlo, senza tenerlo costantemente sotto controllo? E quale strumento migliore che i nostri orologi sempre più precisi e sofisticati?

Se ci fermiamo un attimo a riflettere su quale sia il gesto che, durante una nostra comune giornata, ripetiamo il maggior numero di volte, riconosceremo presto che si tratta del gesto di guardare l’orologio. Un gesto così scontato, ormai istintivo, che quasi come una funzione fisiologica accompagna la nostra esistenza, che ci appare impossibile immaginare una vita senza orologio. Il tempo, pensiamo giustamente, è il giudice supremo ed impietoso della nostra vita: come potremmo vivere senza misurarlo, senza tenerlo costantemente sotto controllo? E quale strumento migliore che i nostri orologi sempre più precisi e sofisticati?

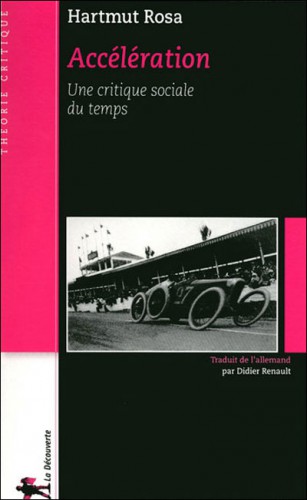

Un livre de plus consacré au temps. Au cours des décennies écoulées on n’a jamais autant écrit sur la condition humaine en relation avec le temps. Beaucoup de sociologues prennent au sérieux la temporalité pour essayer de prouver qu’ils pensent. Il ne faut pas les confondre avec des philosophes puissants comme Dilthey, Ortega et Heidegger, dont les œuvres sont centrées sur cela.

Un livre de plus consacré au temps. Au cours des décennies écoulées on n’a jamais autant écrit sur la condition humaine en relation avec le temps. Beaucoup de sociologues prennent au sérieux la temporalité pour essayer de prouver qu’ils pensent. Il ne faut pas les confondre avec des philosophes puissants comme Dilthey, Ortega et Heidegger, dont les œuvres sont centrées sur cela.