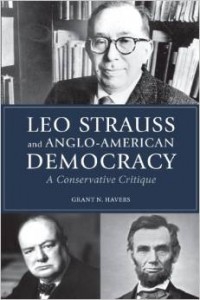

Grant Havers

Leo Strauss and Anglo-American Democracy: A Conservative Critique [2]

Northern Illinois University Press, 2013

Amain pillar sustaining the practice of mass immigration is that Western nations are inherently characterized by a “civic” form of national membership. Western nations express the “natural” wishes of “man as man” for equal rights, rule of law, freedom of expression, and private property. Mainstream leftists and conservatives alike insist on the historical genuineness of this civic definition. This civic identity, they tell us, is what identifies the nations of Western civilization as unique and universal all at once. Unique because they are the only nations in which the idea of citizenship has been radically separated from any ethnic and religious background; and universal because these civic values are self-evident truths all humans want whenever they are given the opportunity to choose.

Amain pillar sustaining the practice of mass immigration is that Western nations are inherently characterized by a “civic” form of national membership. Western nations express the “natural” wishes of “man as man” for equal rights, rule of law, freedom of expression, and private property. Mainstream leftists and conservatives alike insist on the historical genuineness of this civic definition. This civic identity, they tell us, is what identifies the nations of Western civilization as unique and universal all at once. Unique because they are the only nations in which the idea of citizenship has been radically separated from any ethnic and religious background; and universal because these civic values are self-evident truths all humans want whenever they are given the opportunity to choose.

To include the criteria of ethnicity or religious ancestry in the concept of Western citizenship is manifestly illiberal. Even more, it is now taken for granted that if Western nations are to live up to their idea of civic citizenship they must relinquish any sense of European peoplehood and Christian ancestry. Welcoming immigrants from multiples ethnic and religious backgrounds is currently seen as a truer expression of the inherent character of Western nationality than remaining attached to any notion of European ethnicity and Christian historicity.

The reality that the liberal constitutions of Western nations were conceived and understood in ethnic and Christian terms (if only implicitly since the builders and founders of European nations never envisioned an age of mass migrations) has been conveniently overlooked by our mainstream elites. These elites are willfully downplaying the fact that the liberal nation states of Europe emerged within ethnolinguistic boundaries and majority identities. Those states possessing a high degree of ethnic homogeneity, where ancestors had lived for generations—England, France, Italy, Belgium, Holland, Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Denmark—were the ones with the strongest liberal traits, constitutions, and institutions. Those states (or empires like the Austro-Hungarian Empire) composed of multiple ethnic groups were the ones enraptured by illiberal forms of ethnic nationalism and intense rivalries over identities and political boundaries. In other words, the historical record shows that a high degree of ethnic homogeneity tends to produce liberal values, whereas countries or areas with a high number of diverse ethnic groups have tended to generate ethnic tensions, conflict, and illiberal institutions. As Jerry Muller has argued in “Us and Them” (Foreign Affairs: March/April 2008), “Liberal democracy and ethnic homogeneity are not only compatible; they can be complementary.”

Mainstream leftists and conservatives have differed in the way they have gone about redefining the historical roots of Western nationalism and abolishing the ethnic identities of Western nations. Eric Hobsbawm, the highly regarded apologist of the Great Terror [3] in the Soviet Union, persuaded most of the academic world, in his book, Nations and Nationalism since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality [4] (1989), that the nation states of Europe were not created by a people sharing a common historical memory, a sense of territorial belonging and habitation, similar dialects, and physical appearances; no, the nation-states of Europe were “socially constructed” entities, “invented traditions,” “imagined” by people perceiving themselves as part of a “mythological” group in an unknown past. Hobsbawm deliberately sought to discredit any sense of ethnic identity among Europeans by depicting their nation building practices as modern fairy-tales administered by capitalists and bureaucrats from above on a miscellaneous pre-modern population.

(1989), that the nation states of Europe were not created by a people sharing a common historical memory, a sense of territorial belonging and habitation, similar dialects, and physical appearances; no, the nation-states of Europe were “socially constructed” entities, “invented traditions,” “imagined” by people perceiving themselves as part of a “mythological” group in an unknown past. Hobsbawm deliberately sought to discredit any sense of ethnic identity among Europeans by depicting their nation building practices as modern fairy-tales administered by capitalists and bureaucrats from above on a miscellaneous pre-modern population.

Leftists however have not been the only ones pushing for a purely civic interpretation of Western nationhood; mainstream conservatives, too, have been trying to root out Christianity and ethnicity from the historical experiences and founding principles of European nations. Their discursive strategy has not been one of dishonoring the past but of projecting backwards into European history a universal notion of Western citizenship that includes the human race. The most prominent school in the formulation of this view has come out of the writings of Leo Strauss. This is the way I read Grant Havers’s Leo Strauss and Anglo-American Democracy: A Conservative Critique (2013). In this heavily researched and always clear book, Havers goes about arguing in a calm but very effective way that Strauss was not the traditional conservative leftists have made him out to be; he was a firm believer in the principles of liberal equality and a unswerving opponent of any form of Western citizenship anchored in Christianity and ethnic identity.

Strauss’s vehement opposition to communism coupled with his enthusiastic defense of American democracy, as it stood in the 1950s, created the erroneous impression that he was a “right wing conservative.” But, as Havers explains, Strauss was no less critical of “right wing extremists” (who valued forms of citizenship tied to the nationalist customs and historical memories of a particular people) than of the New Left. Strauss believed that America was a universal nation in being founded on principles that reflected the “natural” disposition of all humans for life, liberty, and happiness. These principles were discovered first by the ancient Greeks in a philosophical and rational manner, but they were not particular to the Greeks; rather, they were “eternal truths” apprehended by Greek philosophers in their writings against tyrannical regimes. While these principles were accessible to all humans as humans, only a few great philosophers and statesmen exhibited the intellectual and personal fortitude to fully grasp and actualize these principles. Nevertheless, most humans possessed enough mental equipment as reasoning beings to recognize these principles as “rights” intrinsic to their nature, so long as they were given the chance to deliberate on “the good” life.

Strauss’s vehement opposition to communism coupled with his enthusiastic defense of American democracy, as it stood in the 1950s, created the erroneous impression that he was a “right wing conservative.” But, as Havers explains, Strauss was no less critical of “right wing extremists” (who valued forms of citizenship tied to the nationalist customs and historical memories of a particular people) than of the New Left. Strauss believed that America was a universal nation in being founded on principles that reflected the “natural” disposition of all humans for life, liberty, and happiness. These principles were discovered first by the ancient Greeks in a philosophical and rational manner, but they were not particular to the Greeks; rather, they were “eternal truths” apprehended by Greek philosophers in their writings against tyrannical regimes. While these principles were accessible to all humans as humans, only a few great philosophers and statesmen exhibited the intellectual and personal fortitude to fully grasp and actualize these principles. Nevertheless, most humans possessed enough mental equipment as reasoning beings to recognize these principles as “rights” intrinsic to their nature, so long as they were given the chance to deliberate on “the good” life.

Havers’s “conservative critique” of Strauss consists essentially in emphasizing the uniquely Western and Christian origins of the foundational principles of Anglo-American democracy. While Havers’s traditional conservatism includes admiration for such classical liberal principles as the rule of law, constitutional government, and separation of church and state, his argument is that these liberal principles are rooted primarily in Christianity, particularly its ideal of charity. He takes for granted the reader’s familiarity with this ideal, which is unfortunate, since it is not well understood, but is generally taken to mean that Christianity encourages charitable activities, relief of poverty, and advancement of education. Havers has something more profound in mind. Christian charity from a political perspective is a state of being wherein one seeks a sympathetic understanding of ideas and beliefs that are different to one’s own. Charitable Christians seek to understand other viewpoints and are willing to engage alternative ideas and political proposals rather than oppose them without open dialogue. Havers argues that the principles of natural rights embodied in America’s founding cannot be separated from this charitable disposition; not only were the founders of America, the men who wrote the Federalist Papers, quite definite in voicing the view that they were acting as Christian believers in formulating America’s founding, they were also very critical of Greek slavery, militarism, and aristocratic license against the will of the people.

Throughout the book Havers debates the rather ahistorical way Strauss and his followers have gone about “downplaying or ignoring the role of Christianity in shaping the Anglo-American tradition” – when the historical record copiously shows that Christianity played a central role nurturing the ideals of individualism and tolerance, abolition of slavery and respect for the dignity of all humans. Havers debates and refutes the similarly perplexing ways in which Straussians have gone about highlighting the role of Greek philosophy in shaping the Anglo-American tradition – when the historical record amply shows that Greek philosophers were opponents of the natural equality of humans, defenders of slavery, proponents of a tragic view of history, the inevitability of war, and the rule of the mighty.

Havers also challenges the Straussian elevation of such figures as Lincoln, Churchill, Roosevelt, Hobbes, and Locke as proponents of an Anglo-American tradition founded on “timeless” Greek ideas. He shows that Christianity was the prevailing influence in the intellectual development and actions of all these men. Havers imparts on the readers a sense of disbelief as to how the Straussians ever managed to exert so much influence on American conservatism (to the point of transforming its original emphasis on traditions and communities into a call for the spread of universal values across the world), despite proposing views that were so blissfully indifferent to “readily available facts.”

Havers also challenges the Straussian elevation of such figures as Lincoln, Churchill, Roosevelt, Hobbes, and Locke as proponents of an Anglo-American tradition founded on “timeless” Greek ideas. He shows that Christianity was the prevailing influence in the intellectual development and actions of all these men. Havers imparts on the readers a sense of disbelief as to how the Straussians ever managed to exert so much influence on American conservatism (to the point of transforming its original emphasis on traditions and communities into a call for the spread of universal values across the world), despite proposing views that were so blissfully indifferent to “readily available facts.”

Basically, the Straussians were not worried about historical veracity as much as they were determined to argue that Western civilization (which they identified with the Anglo-American tradition) was philosophically conceived from its beginnings as a universal civilization. In this effort, Strauss and his followers genuinely believed that American liberalism had fallen prey to the “yoke” of German historicism and relativism, infusing the American principles of natural rights with the notion that these were merely valid for a particular people rather than based on Human Reason. German historicism – the idea that each culture exhibits a particular world view and that there is no such thing as a rational faculty standing above history – led to the belittlement of the principles of natural rights by limiting them a particular time and place. Worse than this — and the modern philosophers, Hobbes and Locke, were to be blamed as well — the principles of natural rights came to be separated from the ancient Greek idea that we can rank ways of life according to their degree of excellence and elevation of the human soul. The modern philosophy of natural right merely afforded individuals the right to choose their own lifestyle without any guidance as to what is “the good life.”

Strauss believed that this relativist liberalism would not be able to withstand challenges from other philosophical outlooks and illiberal ways of life, from Communism and Fascism, for example, unless it was rationally grounded on eternal principles. He thought the ancient Greeks had understood better than anyone else that some truths are deeply grounded in the actual nature of men, not relative to a particular time and culture, but essential to what is best for “man as man.” These truths were summoned up in the modern philosophy of natural rights, though in a flawed manner. The moderns tended to appeal to the lower instincts of humans, to a society that would merely ensure security and the pursuit of pleasure, in defending their ideals of liberty and happiness. But with a proper reading of the ancient texts, and a curriculum based on the “Great Books,” the soul of contemporaneous students could be elevated above a life of trivial pursuits.

This emphasis on absolute, universal, and “natural” standards attracted a number of prominent Christians to Strauss. The Canadian George Grant (1918-1988), for one, was drawn to the potential uses Strauss’s emphasis on eternal values might have to fight off the erosion of Christian conviction in the ever more secular, liberal, and consumerist Canada of his day. Grant, Havers explains, did not quite realize that Strauss was neither a conservative nor a Christian but a staunch proponent of a philosophically based liberalism bereft of any Christian identity. Grant relished the British and Protestant roots of the Anglo-American tradition, though there were certain affinities between him and Strauss; Grant was a firm believer in the superiority of Anglo-Saxon civilization and its rightful responsibility in bringing humanity to a higher cultural level. The difference is that Grant affirmed the religious and ethnic particularities of Anglo-Saxon civilization, whereas Strauss, though a Zionist who believed in a Jewish nation state, sought to portray Anglo-American civilization in a philosophical language cleansed of any Christian particularities and European ethnicity.

Strauss wanted a revised interpretation of Anglo-American citizenship standing above tribal identities and historical particularities. Strauss’s objective was to provide Anglo-American government with a political philosophy that would stand as a bulwark against “intolerable” challenges from the left and the right, which endangered liberalism itself. The West had to affirm the universal truthfulness of its way of life and be guarded against the tolerance of forms of expression that threaten this way of life. Havers observes that Strauss was particularly worried about the inability of liberal regimes, as was the case with the Weimar republic, to face up to illiberal challenges. He wanted a liberal order that would ensure the survival of the Jews, and the best assurance for this was a liberal order that spoke in a neutral and purely philosophical idiom without giving any preference to any religious faith and any historical and ethnic ancestries. He wanted a liberalism that would work to undermine any ancestral or traditionally conservative norms that gave preference to a particular people in the heritage of America’s founding, and thereby may discriminate against Jews. Only in a strictly universal civilization would the Jews feel safe while retaining their identity.

Havers brings up another old conservative, Willmore Kendall (1909-68), who was drawn to Straussian thought even though substantial aspects of his thought were incompatible with Strauss’s. Among these differences was the “majoritarian populism” of Kendall versus the aristocratic elitism of Strauss. The aristocrats Strauss had in mind were philosophers and statesmen who understood the eternal values of the West whereas the majoritarian people Kendall had in mind were Americans who were conservative by tradition and deeply attached to their ancestral roots in America, rather than believers in universal rights concocted by philosophers. While Kendall was drawn to Strauss’s scepticism over unlimited speech, what he feared was not the ways in which particular ethnic/religious groups might use free speech to protect their ancestral rights and thereby violate – from Strauss’s perspective – the universality of liberalism, but “the opposite of what Strauss fear[ed]”: that an open society unmindful of its actual historical roots, allowing unlimited questioning of its ancestral identities, against the natural wishes of the majority for their roots and traditions, would eventually destroy the Anglo-American tradition.

Havers brings up as well Kendall’s call for a restricted immigration policy consistent with majoritarian wishes. While Havers is primarily concerned with the Christian roots of Anglo-American democracy, he identifies this view by Kendall with conservatism proper. The Straussian view that America is an exceptional nation by virtue of being founded on the basis of philosophical propositions, which somehow have elevated this nation to be a model to the world, is, in Havers view, closer to the leftist dismissal of religious identities and traditions than it is to any true conservatism. Conservatives, or Paleo-Conservatives, believe that human identities are not mere private choices arbitrarily decided by abstract individuals in complete disregard of history and the natural dispositions of humans for social groupings with similar ethnic and religious identities.

These differences between the Straussians and old conservatives are all the more peculiar since, as Havers notes, Strauss was very mindful of the particular identities of Jewish people, criticizing those who called for a liberalized form of Jewish identity based on values alone. Jews, Strauss insisted, must maintain fidelity to their own nationality rather than to a “liberal theology,” otherwise they would end up destroying their particular historical identity.

Now, Straussians could well respond that the Anglo-American identity is different, consciously dedicated to universal values, but, as Havers carefully shows, this emphasis on the philosophy of natural rights cannot be properly understood outside the religious ancestry of the founders, and (although Havers is less emphatic about this) outside the customs, institutions and ethnicity of the founders. As the Australian Frank Salter has written:

Now, Straussians could well respond that the Anglo-American identity is different, consciously dedicated to universal values, but, as Havers carefully shows, this emphasis on the philosophy of natural rights cannot be properly understood outside the religious ancestry of the founders, and (although Havers is less emphatic about this) outside the customs, institutions and ethnicity of the founders. As the Australian Frank Salter has written:

The United States began as an implicit ethnic state, whose Protestant European identity was taken for granted. As a result, the founding fathers made few remarks about ethnicity, but John Jay famously stated in 1787 that America was ‘one united people, a people descended from the same ancestors,’ a prominent statement in one of the republic’s founding philosophical documents that attracted no disagreement (230) [5].

This idea that Western nations are all propositional nations is not restricted to the United States, but has been applied to the settler nations of Canada and Australia, and the entire continent of Europe, under the supposition that, with the Enlightenment, the nations of Europe came to be redefined by such “universal” values as individual rights, separation of church and state, democracy. As a result, mainstream liberals and conservatives today regularly insist that Europe is inherently a “community of values,” not of ethnicity or religion, but of values that belong to humanity. Accordingly, the reasoning goes, if Europe is to be committed to these values it must embrace immigration as part of its identity. Multiculturalism is simply a means of facilitating the participation of immigrants into this universal culture, making them feel accepted by recognizing their particular traditions, while they are gradually nudge to think in a universal way. But, as Salter points out,

This is hardly a complete reading of Enlightenment ideas, which include the birth of modern nationalism, the democratic privileging of majority ethnicity, and the linking of minority emancipation to assimilation. The Enlightenment also celebrates empirical science including biology, which culminated in man’s fuller understanding of himself as part of nature (213).

Liberals in the 19th century were fervent supporters of nationalism and the essential importance of being part of a community with shared traditions and common ancestry. Eric Hobsbawm’s claim that Europeans nations were “ideological constructs” created without a substantial grounding in immemorial lands, folkways, and ethnos, should be contrasted to the ideas of such liberal nationalists as Camillo di Cavour (1810–1861), Max Weber [6] (1864–1920), and even John Stuart Mill (1806–1873). While these liberals emphasized a form of nationalism compatible with classical liberal values, they were firm supporters of national identities at a time when a “non-xenophobic nationalism” was meant to acknowledge the presence of what were essentially European ethnic minorities within European nations. None of these liberals ever envisioned the nations of Europe as mere places identified by liberal values belonging to everyone else and obligated to become “welcome” mats for the peoples of the world.

Moreover, Enlightenment thinkers were the progenitors of a science of ethnic differences [7], which has since been producing ever more empirical knowledge, and has today convincingly shown that ethnicity is not merely a social construct but also a biological substrate. As Edward O. Wilson, Pierre van den Berghe, and Salter have written, shared ethnicity is an expression of extended kinship at the genetic level; members of an ethnic group are biologically related in the same way that members of a family are related even though the genetic connection is not as strongly marked. Numerous papers – which I will reference below with links — are now coming out supporting the view that humans are ethnocentric and that such altruistic dispositions as sharing, loyalty, caring, and even motherly love, are exhibited primarily and intensively within in-groups rather than toward a universal “we” in disregard for one’s community. Strauss’s concern for the identity of Jews is consistent with this science.

The Straussian language about “natural rights” belonging to “man as man” is mostly gibberish devoid of any historical veracity and scientific support. Hegel long refuted the argument that humans were born with natural rights which they never enjoyed until a few philosophers discovered them and then went on to create ex nihilo Western civilization. Man “in his immediate and natural way of existence” was never the possessor of natural rights. The natural rights the founders spoke about, which were also in varying ways announced in the creation of the nations of Canada and Australia, and prescribed in the modern constitutions of European nations, were acquired and won only through a long historical movement, the origins of which may be traced back to ancient Greece, but which also included, as Havers insists, the history of Christianity and, I would add, the legal history of Rome, the Catholic Middle Ages [8], the Renaissance, Protestant Reformation, the Enlightenment, and the Bourgeois Revolutions.

The Straussians believe that the way to overcome the tendency of liberal societies to relativism or the celebration of pluralistic conceptions of life without any sense of ranking the lifestyle of citizens is to impart reverence and patriotic attachment for the Anglo-American tradition by emphasizing not the heterogeneous identity of this tradition but its foundation in the ancient philosophical commitment to “the good” and the “perfection of humanity.” But this effort to instill national commitment by teaching citizens about the classics of ancient Greece and the great statesmen of liberal freedom is doomed to failure and has been a failure. The problem of nihilism is nonexistent in societies with a strong sense of reverence for traditional practices, authoritative patriarchal figures, and a sense of peoplehood and homeland. The way out of the crisis of Western nihilism is to re-nationalize liberalism, throw away the cultural Marxist notion that freedom means liberation from all identities not chosen by the individual, and accentuate the historical and natural-ethnic basis of European identity.

Recent scientific papers on ethnocentrism and human nature:

Oxytocin promotes human ethnocentrism [9]

Perhaps goodwill is unlimited but oxytocin-induced goodwill is not [10]

Oxytocin Increases Generosity in Humans [11]

Oxytocin promotes group-serving dishonesty [12]

We Take Care of Our Own [13]

Source: http://www.eurocanadian.ca/2014/06/the-straussian-assault-on-americas.html [14]

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Amain pillar sustaining the practice of mass immigration is that Western nations are inherently characterized by a “civic” form of national membership. Western nations express the “natural” wishes of “man as man” for equal rights, rule of law, freedom of expression, and private property. Mainstream leftists and conservatives alike insist on the historical genuineness of this civic definition. This civic identity, they tell us, is what identifies the nations of Western civilization as unique and universal all at once. Unique because they are the only nations in which the idea of citizenship has been radically separated from any ethnic and religious background; and universal because these civic values are self-evident truths all humans want whenever they are given the opportunity to choose.

Amain pillar sustaining the practice of mass immigration is that Western nations are inherently characterized by a “civic” form of national membership. Western nations express the “natural” wishes of “man as man” for equal rights, rule of law, freedom of expression, and private property. Mainstream leftists and conservatives alike insist on the historical genuineness of this civic definition. This civic identity, they tell us, is what identifies the nations of Western civilization as unique and universal all at once. Unique because they are the only nations in which the idea of citizenship has been radically separated from any ethnic and religious background; and universal because these civic values are self-evident truths all humans want whenever they are given the opportunity to choose. Strauss’s vehement opposition to communism coupled with his enthusiastic defense of American democracy, as it stood in the 1950s, created the erroneous impression that he was a “right wing conservative.” But, as Havers explains, Strauss was no less critical of “right wing extremists” (who valued forms of citizenship tied to the nationalist customs and historical memories of a particular people) than of the New Left. Strauss believed that America was a universal nation in being founded on principles that reflected the “natural” disposition of all humans for life, liberty, and happiness. These principles were discovered first by the ancient Greeks in a philosophical and rational manner, but they were not particular to the Greeks; rather, they were “eternal truths” apprehended by Greek philosophers in their writings against tyrannical regimes. While these principles were accessible to all humans as humans, only a few great philosophers and statesmen exhibited the intellectual and personal fortitude to fully grasp and actualize these principles. Nevertheless, most humans possessed enough mental equipment as reasoning beings to recognize these principles as “rights” intrinsic to their nature, so long as they were given the chance to deliberate on “the good” life.

Strauss’s vehement opposition to communism coupled with his enthusiastic defense of American democracy, as it stood in the 1950s, created the erroneous impression that he was a “right wing conservative.” But, as Havers explains, Strauss was no less critical of “right wing extremists” (who valued forms of citizenship tied to the nationalist customs and historical memories of a particular people) than of the New Left. Strauss believed that America was a universal nation in being founded on principles that reflected the “natural” disposition of all humans for life, liberty, and happiness. These principles were discovered first by the ancient Greeks in a philosophical and rational manner, but they were not particular to the Greeks; rather, they were “eternal truths” apprehended by Greek philosophers in their writings against tyrannical regimes. While these principles were accessible to all humans as humans, only a few great philosophers and statesmen exhibited the intellectual and personal fortitude to fully grasp and actualize these principles. Nevertheless, most humans possessed enough mental equipment as reasoning beings to recognize these principles as “rights” intrinsic to their nature, so long as they were given the chance to deliberate on “the good” life. Havers also challenges the Straussian elevation of such figures as Lincoln, Churchill, Roosevelt, Hobbes, and Locke as proponents of an Anglo-American tradition founded on “timeless” Greek ideas. He shows that Christianity was the prevailing influence in the intellectual development and actions of all these men. Havers imparts on the readers a sense of disbelief as to how the Straussians ever managed to exert so much influence on American conservatism (to the point of transforming its original emphasis on traditions and communities into a call for the spread of universal values across the world), despite proposing views that were so blissfully indifferent to “readily available facts.”

Havers also challenges the Straussian elevation of such figures as Lincoln, Churchill, Roosevelt, Hobbes, and Locke as proponents of an Anglo-American tradition founded on “timeless” Greek ideas. He shows that Christianity was the prevailing influence in the intellectual development and actions of all these men. Havers imparts on the readers a sense of disbelief as to how the Straussians ever managed to exert so much influence on American conservatism (to the point of transforming its original emphasis on traditions and communities into a call for the spread of universal values across the world), despite proposing views that were so blissfully indifferent to “readily available facts.” Now, Straussians could well respond that the Anglo-American identity is different, consciously dedicated to universal values, but, as Havers carefully shows, this emphasis on the philosophy of natural rights cannot be properly understood outside the religious ancestry of the founders, and (although Havers is less emphatic about this) outside the customs, institutions and ethnicity of the founders. As the Australian Frank Salter has written:

Now, Straussians could well respond that the Anglo-American identity is different, consciously dedicated to universal values, but, as Havers carefully shows, this emphasis on the philosophy of natural rights cannot be properly understood outside the religious ancestry of the founders, and (although Havers is less emphatic about this) outside the customs, institutions and ethnicity of the founders. As the Australian Frank Salter has written: