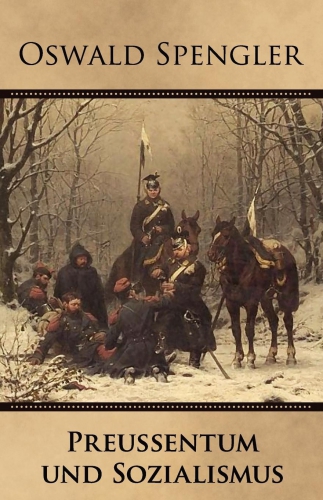

El socialismo corporativo y

tradicionalista de Oswald

Spengler.

Crítica de la

modernidad y de las fantasías

democratistas.

Carlos Javier Blanco Martín

Doctor en Filosofía

Ex: http://www.revistalarazonhistorica.com/21-8-1/

Resumen

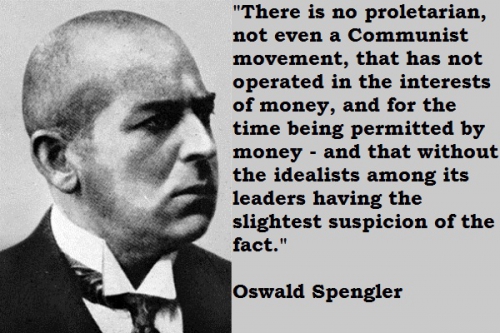

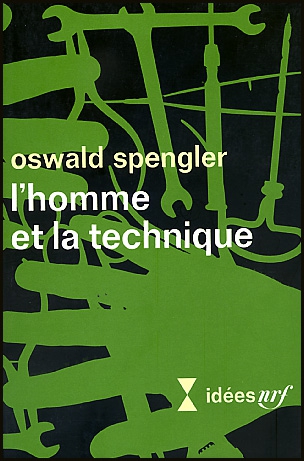

En este trabajo tratamos de exponer las ideas del filósofo alemán Oswald Spengler sobre el socialismo y la nación, expuestas de manera muy notable en su obra Años de Incertidumbre [Jahre der Entscheidung]. Se vislumbra en este libro una teoría político-social para la Europa del porvenir, y no solo una visión pesimista y fatal, como es costumbre.

Abstract

In this work we present the ideas of German philosopher Oswald Spengler on socialism and the nation, most notably exposed in his book Hour of Decision [Jahre der Entscheidung]. This book can be seen in the line of a political and social theory for the Europe of the future, and not just like a pessimistic and fatal vision, as is customary.

***

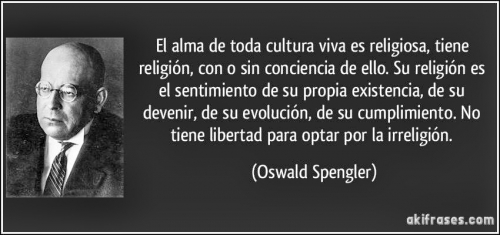

En este trabajo tratamos de exponer las ideas del filósofo alemán Oswald Spengler sobre el socialismo y la nación, expuestas de manera muy notable en su obra Años de Incertidumbre [Jahre der Entscheidung]. Spengler es recordado, principalmente, como un notable e inquietante filósofo de la Historia. Su magna obra, La Decadencia de Occidente [Der Untergang des Abendlandes] contiene numerosas claves para enfrentarse al esquema lineal y “progresista” de la Historia. No hay una Historia Universal sino un número determinado de grandes Culturas cuyo ciclo vital acaba en una fase de rigidez, fosilización, vaciado de contenido aun preservado sus formas. Esto ya no recibe el nombre de Cultura sino más bien, el de Civilización. Pues bien, Occidente se encuentra hoy en una fase de Civilización, de decadencia, de pérdida de sus contenidos bajo rígidas formas. Ineluctablemente, las ideologías socialistas, igualitarias, democráticas, forman parte de esa decadencia, frente a una añorada aristocracia que, de manera harto significativa, Spengler cree posible resucitar. Ello ha de ser a través de un socialismo no marxista, vagamente descrito en términos corporativistas, marcado por los principios de la disciplina, el esfuerzo y la voluntad de poderío. Es así que se vislumbra en este libro una teoría político-social para la Europa del porvenir, y no solo una visión pesimista y fatal, como es costumbre.

En este trabajo tratamos de exponer las ideas del filósofo alemán Oswald Spengler sobre el socialismo y la nación, expuestas de manera muy notable en su obra Años de Incertidumbre [Jahre der Entscheidung]. Spengler es recordado, principalmente, como un notable e inquietante filósofo de la Historia. Su magna obra, La Decadencia de Occidente [Der Untergang des Abendlandes] contiene numerosas claves para enfrentarse al esquema lineal y “progresista” de la Historia. No hay una Historia Universal sino un número determinado de grandes Culturas cuyo ciclo vital acaba en una fase de rigidez, fosilización, vaciado de contenido aun preservado sus formas. Esto ya no recibe el nombre de Cultura sino más bien, el de Civilización. Pues bien, Occidente se encuentra hoy en una fase de Civilización, de decadencia, de pérdida de sus contenidos bajo rígidas formas. Ineluctablemente, las ideologías socialistas, igualitarias, democráticas, forman parte de esa decadencia, frente a una añorada aristocracia que, de manera harto significativa, Spengler cree posible resucitar. Ello ha de ser a través de un socialismo no marxista, vagamente descrito en términos corporativistas, marcado por los principios de la disciplina, el esfuerzo y la voluntad de poderío. Es así que se vislumbra en este libro una teoría político-social para la Europa del porvenir, y no solo una visión pesimista y fatal, como es costumbre.

- Crítica de la idea burguesa de Democracia y de sus fantasías.

Quien vive dentro de una época dada y en el seno de una Civilización determinada, difícilmente se ve libre de las palabras-trampa que en algún momento auroral o clásico se acuñan y se extienden más allá de su prístino contexto. Palabras como Democracia, Socialismo, Libertad y Estado, pongamos como ejemplos, son palabras-trampa desde hace mucho tiempo para la inmensa mayor parte de nuestros contemporáneos. A decir verdad, ¿quién podría salirse de la pecera en que vive el hombre europeo, el de occidente, el hombre del siglo XXI que es siglo de la Democracia mediática, siglo de la Técnica. Es un tipo de individuo que fuera de una pecera epocal y cultural se moriría, no podría pensar ni hablar, ni comprender nada.

Por ello, las palabras-trampa suelen emplearse en los debates públicos, las más de las veces, con un sentido dicotómico, maniqueo. Democracia versus Fascismo; Sociedad de Mercado versus Socialismo, Dictadura versus Mundo Libre. Las terceras vías, o los sentidos y matices infinitos que hubo y hay agazapados en cada uno de los polos de la dicotomía se van perdiendo. Se pierden incluso en el público pretendidamente “culto”. El público lector de periódicos, el hombre de la gran ciudad, instruido, “inteligente” (en el sentido spengleriano de la palabra).

Tomemos el caso de la Democracia, por ejemplo. La propia palabra implica un “Poder”, un ejercicio de la autoridad. La crisis de la Democracia es, hoy, una verdadera crisis de la autoridad. Mantienen al “pueblo” en el sueño de que éste es libre de elegir entre una serie de opciones prefabricadas, predeterminadas por grandes organizaciones electorales, financiadas por un entramado de bancos, grupos empresariales y, a veces, gobiernos extranjeros. El “pueblo” al que se quiere dirigir toda esa maquinaria electoral a la caza de sus votos ha sido, en una medida enorme, nivelado y adiestrado para participar en el juego aritmético de votos. Con el advenimiento del poder de la burguesía, bajo la ficción aritmética de “un hombre, un voto”, se ha querido subordinar la Política a la Economía, nivelando aquella y conservando la jerarquización en ésta. Pues en toda sociedad hay jerarquías, como hay autoridad, si es que se vive en un cierto grado de civilización y no en el rudo primitivismo. La jerarquización preburguesa venía dada por parámetros estrictamente políticos que sólo de una manera secundaria eran raciales, profesionales, meritocráticos. Existía un Orden y ese Orden social era toda una pauta de legibilidad. Las actividades económicas no sólo se realizaban, si es que se realizaban de una manera activa, con vistas a huir de la muerte y sostener la vida, sino para mantener el decoro de cada posición, ajustarse al Orden establecido, mantener a los estamentos improductivos, etc. Lo económico era un medio, no un fin y el Orden social se había ido diversificando a lo largo de la Edad Media a partir de las clases sociales originarias: nobleza, clero y campesinado.

El concepto de Pueblo “con Poder” poseía raíces muy antiguas. Puede encontrarse ya, por lo que sabemos, en todos los grupos étnicos indoeuropeos. Diversas formas de Asamblea (Thing), reuniones de hombres armados, senados, etc. , se encuentran entre los celtas, germanos, romanos y griegos arcaicos. Este Poder de un Pueblo no se veía reñido, en modo alguno, con ideas fundantes tales como realeza, aristocracia, sacerdocio regio, división tri-funcional de la sociedad, jerarquía. En los tiempos arcaicos y en los clásicos tenemos un concepto aristocrático de Democracia, cuya versión más conocida es la ateniense. Tan solo con el paso de una comunidad orgánica a una sociedad de índole atomístico y mecánico podemos comprender la transformación radical que ha experimentado el concepto de Democracia, que es la que media entre el mundo antiguo y medieval, de una parte y el mundo moderno, de la otra. El mundo moderno es el mundo burgués. Los individuos y no las comunidades orgánicas son los elementos únicos y a priori de una sociedad: esta sociedad, en rigor, se autoconstituye como un Mercado y el lazo jurídico que une a individuos distintos, como átomos separados en un medio vacío, es la forma que envuelve un contenido material: compra-venta, intercambio económico de bienes y servicios. Pero esta forma “social” o más bien económica encubre, como enseñó Marx, un contenido basado en la explotación de unos individuos sobre otros.

Hablamos aquí, pues, de una Democracia basada en la Comunidad Orgánica, contrapuesta y a mil años-luz de la Democracia formal basada en la Sociedad Mecánica, basada nada más que en unos lazos formales, jurídicos, que expresan una dinámica económica que recubre la explotación. La Democracia de una Comunidad Orgánica, un Pueblo, hunde sus raíces muy al fondo, en el inconsciente colectivo y en la larga historia de los pueblos europeos, tanto los celtogermánicos como los grecorromanos. En estos pueblos antiguos, antes de sus deformaciones oligárquicas, cesaristas, el principio aristocrático y el principio meritocrático no se enfrentaban, como hoy se nos enfrentan. En la etapa en que se encontraban “en forma”, es decir, con una perfecta acomodación de sus formas, de sus disposiciones para la supervivencia ante el enemigo exterior y para crear y canalizar la agresividad ante los peligros interiores, había medios para que los individuos mejor dotados ejercieran bellamente –y no solo eficazmente- sus capacidades de índole física tanto como mental. En una Comunidad Orgánica la vida es “total” en un sentido muy otro del que hoy conocemos como el nombre de “estados totalitarios”. Para un liberal de nuestro tiempo, la polis griega hubiera debido parecerle un totalitarismo insoportable, mas para el griego perfectamente integrado en ella, ese sentido moderno de “individuo” que a regañadientes paga impuestos o sirve rezongando al Estado con las armas, cuando se le requiere, no tendría otro nombre: traición. Es tan inconmensurable el sentido orgánico de Comunidad, que parte de una diferenciación de los individuos según funciones estrictamente separadas (vide La República, de Platón), con la moderna democracia aritmética y mecánica-formal, que el empleo de un mismo término parece un completo abuso.

Repetimos: Democracia supone un “Pueblo” y supone “Cracia”, esto es, Poder o Autoridad. En la democracia formal actual interesa al Poder realmente constituido la existencia de una masa homogénea. Se trata de un Poder financiero y de corporaciones transnacionales, poderes heterónomos que exigen que por debajo exista una completa nivelación, como es la propia de los sistemas sociales fundados en el capitalismo. La regulación de lo social y de lo político por medio de los criterios del mercado y la obtención de plusvalía no pude significar más que la decadencia y dejadez de lo social y lo político. La Comunidad ha de plegarse y recortarse a las necesidades de la Economía, y de forma anómala en la Historia, en Occidente, como en ninguna otra civilización, no es la Economía un órgano subordinado a la Comunidad, sino el regulador de ésta, hasta el punto de metamorfosearla, destruirla, disgregarla en un agregado de átomos. Pero en realidad cada átomo por separado es casi nada, es un ente desprovisto de alma y de poder. Solamente la agregación aritmética de millones de átomos previamente dirigidos, adiestrados, manipulados –a veces hasta la violencia- es la que da “justificación” al Poder, un Poder previamente arrogado, impuesto, que siempre apuesta al caballo ganador, porque los caballos por los que se puede apostar con cierto realismo ante las urnas son todos suyos.

La desaparición de las libertades concretas está en la base de la proclamación cacareada de una Libertad Universal y Formal. A partir de la premisa de que todo individuo-átomo puede elegir partido en calidad de elector, y de que su voto –como unidad numérica- vale tanto como el de un banquero, se pretende alzar el edificio de una Democracia basada en agregaciones de microdecisiones, al tiempo que se obturan todos los caminos para ejercer una libertad material en los demás órdenes de la vida. En la Democracia Formal se ven proscritos los instintos de aventura, de conquista, de inventiva, de riesgo. El liberalismo moderno conserva tales términos como valores supremos pero circunscritos de manera rígida al ámbito empresarial. Como quiera que una filosofía haga suyos estos valores al margen del economicismo, inmediatamente será tachada con los peores epítetos de nuestro tiempo: fascista, belicista, etc. El sistema capitalista moderno desea que, al margen de la actividad empresarial lucrativa, la “iniciativa” desaparezca de los individuos. Otras instancias han de ser las que posean el “derecho” (más bien el privilegio) de la iniciativa: el Estado, las empresas, diversas fundaciones y organizaciones filantrópicas, etc.

Además, debe tenerse presente un dato fundamental: el Estado ha ido perdiendo su soberanía en el terreno de las grandes decisiones económicas, y se ve reducido a un papel de mero administrador y ejecutor de decisiones tomadas desde fuera, desde un medio de poderes financieros extra-estatales y supra-estatales. Con esta internacionalización de la Economía y la rebaja de soberanía de los estados, éstos han ido ganando terreno en el ámbito de la justificación. A medida que son menos “intensos” en el ejercicio efectivo del Poder, los estados han devenido más extensos en los ámbitos de su administración. A menos Poder efectivo más necesidad de legitimación.

Todavía en 1868, en España, un país retrasado e imperfecto en su proceso de construcción del Estado-nación, podía reconocerse el minimum que un Reino podía hacer para inventarse un Estado nacional: enseñanza reglada y servicio militar, ambos obligatorios, bandera, himno, edificios públicos, historiadores oficialistas y demás intelectuales creadores de mitos colectivos, estatuas de héroes y demás monumentos públicos. Madrid se puso, muy tardíamente, a construir todo esto, con una torpeza e ineficiencia que llega hasta hoy, y que se hace más patente en el Norte de la península, donde el mito de la españolidad unitaria es menos potente. Los liberales decimonónicos poseían una visión muy elemental y ruda de lo que era el estado: el control de los cuarteles militares y de las escuelas, una burguesía que acumulara el capital y se concentrara cerca de la Corte, etc.

Por el contrario, el Estado de perfil postindustrial en toda Europa no ha hecho más que engordar y extenderse. Está ávido por “detectar problemas sociales” y con afán legitimador se inmiscuye en la esfera privada, hasta unos niveles orwellianos. Si un niño no va a la escuela, si un padre le da un bofetón a su hijo, si a un extranjero le miran con desconsideración en una cola de un ayuntamiento, si hay una riña en el seno de una pareja, si en un foro de Internet alguien ofende o se va de la lengua… en todos estos casos que, no ha mucho, se consideraban propios de la esfera privada, ahora son competencia del estado y, de no entrometerse, corre el riesgo este estado de ser acusado de “dejación”. Por todas partes el estado anda a la caza de “injusticias”. Esta actitud, desde luego, no tiene ya nada de liberal, y menos aún de socialista. Un Estado providencia y un Estado paternal y omnisciente como tan solo podía serlo el Dios judío… es un Dios en la Tierra, un ente paternal pero al que nada se le escapa: un gran Ojo.

Por el contrario, el Estado de perfil postindustrial en toda Europa no ha hecho más que engordar y extenderse. Está ávido por “detectar problemas sociales” y con afán legitimador se inmiscuye en la esfera privada, hasta unos niveles orwellianos. Si un niño no va a la escuela, si un padre le da un bofetón a su hijo, si a un extranjero le miran con desconsideración en una cola de un ayuntamiento, si hay una riña en el seno de una pareja, si en un foro de Internet alguien ofende o se va de la lengua… en todos estos casos que, no ha mucho, se consideraban propios de la esfera privada, ahora son competencia del estado y, de no entrometerse, corre el riesgo este estado de ser acusado de “dejación”. Por todas partes el estado anda a la caza de “injusticias”. Esta actitud, desde luego, no tiene ya nada de liberal, y menos aún de socialista. Un Estado providencia y un Estado paternal y omnisciente como tan solo podía serlo el Dios judío… es un Dios en la Tierra, un ente paternal pero al que nada se le escapa: un gran Ojo.

Pero, a la vez… ¿quién pone su fe realmente en este tipo de estado? ¿Quién, de entre los ciudadanos suyos, va a gastar sus energías en reverencias, en veneración, en sentimientos patrióticos, situándose frente a un estado-máquina del que ha desaparecido todo carisma, todo proyecto, todo destino. El Estado europeo –mucho menos el español, fallido en tantos aspectos- ya no “ilusiona”, ya no “despierta fervor”. A las masas se les ha inyectado el mensaje del fin de la Historia: se les hace creer que no existen enemigos externos, cuando en realidad Europa reposa sobre varios polvorines, y sus muros son osmóticos, porosos, diariamente franqueados por extranjeros que, una vez que ponen pies en la fortaleza pueden tranquilamente decir, sin más que invocar su condición humana: ¡esta tierra es mía! El Estado del siglo XXI pretende ser un Estado pacificado, una neutralización permanente y universal del conflicto.

Sin embargo hay conflictos. El mundo es así, no hay quien lo cambie. Heráclito, en los albores mismos de la filosofía, supo verlo. Ante cualquier estado de las cosas surge al momento la antítesis, una contra-realidad que se le enfrenta. El Estado, al alzarse como el “gran pacificador”, se torna totalitario bajo el pretexto de hacerle la guerra al totalitarismo; y la misma Comunidad Internacional deviene totalitaria y excluyente al someterse a un Orden Mundial hegemónico donde toda guerra particular queda –en el instante- cifrada como Guerra Mundial, guerra del Estado delincuente contra la Humanidad.

El horror al conflicto agrava los conflictos, los totaliza. El deseo compulsivo del Estado es hacer de sus masas ciudadanas unas verdaderas hordas consumistas, que no presenten resistencia a nada “al margen de los canales adecuados” que, como siempre, acaban siendo las urnas y las protestas inocuas, donde –en situación ideal para la Democracia Formal- “no se va contra nadie ni contra nada- y más bien lo que se hace es “manifestarse”. El estado de perpetuo no-conflicto se lleva a efecto con este estilo “expresivo” de entender la política, que es la simple pose, la actitud impotente de quien dice “me gusta” o “no me gusta”. En realidad, es una transposición de la utopía de los consumidores libres y satisfechos, que entienden la sociedad como un mercado de bienes entre los que puede optar. Pues bien, así también el “rebelde” de nuestro tiempo puede optar entre una pose y otra, pero nunca llegar a la dialéctica de los “puños y pistolas”. Eso no, eso nunca. La lucha de clases de que hablaba el marxismo, la política de barricadas y de huelgas generales pretende ser “historia”, y hay quien se cree revolucionario en nuestros días firmando manifiestos por Internet. Nunca estuvo tan bien visto parecer “revolucionario” y hasta cierta derecha conservadora ha adoptado eslóganes que parecen sacados del Museo del Mayo de 1968, entre momias melenudas y barbudas: “¡Rebélate!” “¡Hazles frente!”. En realidad quienes hablan así, saborean el café ante el teclado del ordenador o ante la pantalla de televisión. En este lado del mundo nadie arriesga nada, y todos juegan. Se sabe, vagamente, que algunos negritos de continentes perdidos montan para nosotros el móvil o tejen la ropa que, a precios económicos, llevamos encima. Pero las samaritanas y las monjitas también pueden tener sus lados oscuros, nos dicen, y de conocerlas también se encargan los mass media, que distribuyen multitud de mensajes, entre los cuales la excesiva caridad también “ha de discurrir por sus cauces”.

El heroísmo, buscar el destino y seguirlo trágicamente hasta el final, vivir la vida al margen de la mentalidad burguesa, comercial, eso es hoy lo criminal. En el contexto de un Estado sin destino, dentro del cual no se reconoce un Pueblo, sino una masa nivelada de gentes de diverso origen y pelaje, quien hable en nombre del Pueblo –real o inventado, da igual- es ipso facto entendido como un criminal. Máxime si, como sucede en los tiempos modernos, el Estado reclama para sí el monopolio de la violencia. Cualquier banda armada, antes de iniciar sus acciones, ya es punible por el mero hecho de llevar consigo el armamento. La autodefensa de los particulares, de los grupos vecinales, de los pueblos y de las etnias, todo ello queda proscrito.

En una Europa entendida como “nación de naciones”, la homogeneidad de cada uno de sus pueblos constituyentes, así como la distinta pureza de sus rasgos diferenciados, son fenómenos que han se mantenido de manera vigorosa hasta la Revolución Industrial. Justamente esta agresión fatal del “espíritu de ciudad” sobre el “alma del campo”, se detecta el cambio de papel de los Estados: su función de garantes de la burguesía y del ansia de acumulación de Capital no hizo más que exterminar cualquier realidad que se le pusiera por delante. Era necesario laminar toda Comunidad Orgánica (por ejemplo, la Comunidad Campesina), en el campo tanto como la vida gremial y corporativa en la ciudad. Era preciso reconocer individuos y solo individuos y, ante ellos se alzará la empresa capitalista, el agente creado exclusivamente para la obtención de plusvalía por medio de la explotación del trabajador, arrasando, de paso, todo paisaje, todo equilibrio natural, toda tradición, toda moral.

En la fase tan avanzada del capitalismo en que ahora vivimos, parece que se renuevan los “instintos” de las etnias y las agrupaciones no economicistas. Las monjitas del progresismo, da igual si de signo liberal o socialdemócrata, se asustaron con ello y dirigieron a sus plegarias a las “Instituciones” que veneraban. Al estallar la desmembración de Yugoslavia y al regresar con fuerza el principio identitario, después de dos siglos de oscurecimiento jacobino, estas mismas criaturas se tuvieron que enterar de la impotencia, la pasividad o la perversidad de toda la OTAN, de toda la Unión Europea, de toda la ONU, y demás nidos de burócratas y parásitos. Los pueblos y las bandas agarraron las armas y se masacraron entre sí, en fechas no tan lejanas de aquel 1945 en el que, derrotado el Reich, se había gritado “¡Nunca más!”.

2. El nacionalismo de Oswald Spengler

Con estas palabras podemos dejar que el propio filósofo germano exprese su idea de nación:

``Con el siglo XIX, las potencias pasan de la forma del Estado dinástico a la del Estado nacional. Pero ¿qué significa esto? Naciones, esto es, pueblos de cultura, había ya desde mucho tiempo atrás. En gneral, coincidían también con el área de poderío de las grandes dinastías. Estas naciones eran ideas en en el dentido en que Goethe habla de la idea de su existencia: la forma interior de una vida importante que, inconsciente e inadvertidamente, se realiza en cada hecho y en cada palabra. Pero „la nation“ en el sentido de 1789 era un ideal racionalista y romántico, una imagen optativa de tendencia manifiestamente política, por no decir social. Esto no puede ya nadie distinguirlo en esta época obtusa. Un ideal es un resultado de la reflexión, un concepto o una tesis, que ja de ser formulado para „tener“ el ideal. A consecuencia de ello, se convierte al poco tiempo en una frase hecha que se emplea sin darle ya contenido mental alguno. En cambio, las ideas son sin palabras. Rara vez, o nunca, emergen en la conciencia de sus sustratos y apenas pueden ser aprehendidas por todos en palabras. Tienen que ser sentidas en la imagen del suceder y descritas en sus realizaciones. No se dejan definir. No tienen nada que ver con deseos ni con fines. Son el oscuro impulso que adquiere forma en una vida y tiende, a manera de destino, allende la vida individual, hacia una dirección: la idea del romanticismo, la idea de las Cruzadas, la idea faústica de la aspiración al infinito“ [1][i].

„Mit dem 19. Jahrhundert gehen die Mächte aus der Form des dynastischen Staates in die des Nationalstaates über. Aber was heißt das? Nationen, das heißt Kulturvölker, gab es natürlich längst. Im großen und ganzen deckten sie sich auch mit den Machtgebieten der großen Dynastien. Diese Nationen waren Ideen, in dem Sinne wie Goethe von der Idee seines Daseins spricht: die innere Form eines bedeutenden Lebens, die unbewußt und unvermerkt sich in jeder. Tat, in jedem Wort verwirklicht. »La nation« im Sinne von 1789 war aber ein rationalistisches und romantisches Ideal, ein Wunschbild von ausdrücklich politischer, um nicht zu sagen sozialer Tendenz. Das kann in dieser flachen Zeit niemand mehr unterscheiden. Ein Ideal ist ein Ergebnis des Nachdenkens, ein Begriff oder Satz, der formuliert sein muß, um das Ideal zu »haben«. Infolgedessen wird es nach kurzer Zeit zum Schlagwort, das man gebraucht, ohne sich noch etwas dabei zu denken. Ideen dagegen sind wortlos. Sie kommen ihren Trägern selten oder gar nicht zum Bewußtsein und sind auch von anderen kaum in Worte zu fassen. Sie müssen im Bilde des Geschehens gefühlt, in ihren Verwirklichungen beschrieben werden. Definieren lassen sie sich nicht. Mit Wünschen oder Zwecken haben sie nichts zu tun. Sie sind der dunkle Drang, der in einem Leben Gestalt gewinnt und über das einzelne Leben hinaus schicksalhaft in eine Richtung strebt: die Idee des Römertums, die Idee der Kreuzzüge, die faustische Idee des Strebens ins Unendliche.“ [1][ii]

Las naciones son „pueblos culturales“ [Nationen, das heißt Kulturvölker]. Hunden sus raíces en los tiempos oscuros de la barbarie, pero en la Edad Media, como ideas que son de distintas formas vitales. En Europa las naciones adquieren forma en el medievo por medio de las grandes dinastías. Una idea, en la Historia, es un impulso o fuerza directiva que no admite una expresión con palabras [Ideen dagegen sind wortlos]. Las verdaderas naciones –en el sentido europeo- son ideas y no ideales. Arrojan una sucesión de realizaciones (Verwirklichungen). Las creaciones y logros efectivamente llevados a cabo son las únicas cosasque admiten descripción, mas las ideas por sí mismas –según Spengler- son inaprensibles por medio del lenguaje y de los razonamientos. Se opone aquí el razonamiento discursivo a la intuición. La nación se vive, se intuye. Es una idea de una forma viviente, no un ideal. Pero a partir de la Modernidad y, especialmente, a partir de la Revolución Francesa, la idea se confunde con el ideal. Aquellos que construyen discursos razonados en pro de un ideal, una utopía, un deseo al que la inteligencia deba encaminarse, se mueven en la órbita del puro racionalismo. Sus ideales siempre muestran el cariz artificioso y falso de una mera construcción. Sus acciones son medios para un fin racionalmente concebido.

La nación de ciudadanos, que son ciudadanos precisamente a partir de la ley, la Constitución o el Pacto social originario, es nación artificiosa, es una suerte de polis agrandada. La nación verdadera brota del Pueblo y fue moldeada por sus nobles y príncipes y ante todo, según Spengler, es impulso (Drang). Muchos nacionalismos, muchos ideales soberanistas son hoy un simple resultado de razonamientos y de discursos artificiosos. El Democratismo propala la idea del derecho a decidir. Basta con que un colectivo de personas, abstractamente separado de los demás por criterios a menudo peregrinos, decida en votación subitánea constituírse en Nación para acceder a un Estado. A esto lo llaman hoy derecho de autodeterminación, derecho a decidir. Pero observando la Historia de Europa a más largo plazo, y sin dejarse embaucar por los prejuicidos del Racionalismo y del Romanticismo, la nación es Impulso e Idea (ambos inexpresables) y no la conclusión de silogismos o el resultado de distingos intelectuales.

El nacionalismo de los racionalistas y románticos es obra de un grupo reducido de intelectuales que suelen hablar en nombre del Pueblo, pero en realidad ese sustrato popular al que apelan no suele hablar el mismo lenguaje que las élites. El pueblo no se expresa por medio de conceptos sofisticados y discursos racionales. El pueblo da la espalda a los intelectuales que pretenden dirigirle como si fueran pastores hacia un ideal si este ideal se contrapone a la idea de la que ellos son sustancia. Idea e ideal se contraponen, y si no existe coincidencia entonces el pueblo no llega a contar con Estado propio, esto es, con un aparato que garantice la cohesión y la fuerza hacia afuera. Sobre el Estado escribe Spengler:

``Los Estados son unidades puramente políticas, unidades del poder que actúa hacia afuera. No están ligados a unidades de raza, idioma o religión, sino por encima de ellas. Cuando coinciden o pugnan con tales unidades, su fuerza se hace menor a consecuencia de la contradicción interna, nunca mayor. La política exterior existe tan sólo para asegurar la fuerza y la unidad de la exterior. Allí donde persigue fines distintos, particulares, comienza la decadencia, el ``perder forma´´ del Estado.“ [1][iii]

„Staaten sind rein politische Einheiten, Einheiten der nach außen wirkenden Macht. Sie sind nicht an Einheiten der Rasse, Sprache oder Religion gebunden, sondern sie stehen darüber. Wenn sie sich mit solchen Einheiten decken oder kreuzen, so wird ihre Kraft infolge des inneren Widerspruches in der Regel geringer, nie größer. Die innere Politik ist nur dazu da, um die Kraft und Einheit der äußeren zu sichern. Wo sie andere, eigene Ziele verfolgt, beginnt der Verfall, das Außer-Form-Geraten des Staates.“[1][iv]

La Decadencia(Verfall) se inicia, pues, con la contraposición entre fines distintos, que llegan a hacerse incompatibles entre sí. Toda la teoria marxiana de la Lucha de Clases podría releerse como teoría de la decadencia de una civilización. La unidad de lucha ante el exterior –que es el Estado- se transforma en una una superficie cuarteada, pues las clases economicistas persiguen fines incompatibles. El desenvolvimiento del Capitalismo es también el nacimiento de unos ideales fantásticos –las clases internacionalistas- que se olvidan del Estado, lo liquidan, lo manejan a su antojo, como instrumento para ahogar y vencer a la clase enemiga, como medio de explotación, como aparato de represión, o como ídolo al que derribar. Anarquismo e instrumentalismo coinciden epocalmente. No están solos los anarquistas en el vilipendio y enemiga contra el estado. Los liberales y los socialistas parten de la doctrina del estado civil como mal menor, como instrumento a duras penas soportable y tolerado siempre que pueda ser prostituído con algún concreto fin: la fraternidad universal, el perfecto mercado autorregulado o lo que sea. Socialismo, comunismo y liberalismo son ideologías que encuentran una contradicción (Widerspruch) entre el Estado original y genuino –creado hacia fuera, frente a un enemigo exterior- y el espíritu industrial (Spencer) pacífico, cansado, que desea ante todo un descanso en el trabajo, un orden público para producir más y mejor.

Los periodos de paz un tanto prolongados crean la ilusión de que se puede vivir sin defensa, sin armas, sin dominio y contradominio. Pero la política es la política de la paz y la política de la guerra, y ambos estados se sitúan en un contínuo. Los estados oscilan entre acciones bélicas y acciones pacíficas. Hay guerras que avocan a una paz, y hay tratados de paz que avocan a la guerra. En toda relación entre estados hay –en cada momento- vencedores y vencidos, y los puntos de equilibrio son pasajeros, son idealizaciones temporales, imágenes posibles desde el punto de vista mental, pero cuya realización histórico-física no puede durar más allá de un instante, a la manera como se podría fotografíar un cono apoyado sobre su vértice en la horizontal del suelo justo antes de caerse.

``La historia humana en la edad de las culturas superiores es la historia de los poderes políticos. La forma de esta historia es la guerra. También la paz forma parte de ella. Es la continuación de la guerra con otros medios: la tentativa, por parte de los vencidos, de libertarse de las consecuencias de la guerra en forma de tratados y la tentativa de mantenerlos por parte del vencedor. Un estado es el „estar en forma“ (...) de una unidad nacional por él constituída y representada para guerras reales y posibles. Cuando esta forma es muy vigorosa, posee ya, como tal, el valor de una guerra victoriosa ganada sin armas, sólo por el peso del poder disponible. Cuando es débil, eqivale a una derrota constante en las relaciones con otras potencias.“ [1][v]

„Menschliche Geschichte im Zeitalter der hohen Kulturen ist die Geschichte politischer Mächte. Die Form dieser Geschichte ist der Krieg. Auch der Friede gehört dazu. Er ist die Fortsetzung des Krieges mit andern Mitteln: der Versuch des Besiegten, die Folgen des Krieges in der Form von Verträgen abzuschütteln, der Versuch des Siegers, sie festzuhalten. Ein Staat ist das »In Form sein« einer durch ihn gebildeten und dargestellten Menschliche Geschichte im Zeitalter der hohen Kulturen ist die Geschichte politischer Mächte. Die Form dieser Geschichte ist der Krieg. Auch der Friede gehört dazu. Er ist die Fortsetzung des Krieges mit andern Mitteln: der Versuch des Besiegten, die Folgen des Krieges in der Form von Verträgen abzuschütteln, der Versuch des Siegers, sie festzuhalten. Ein Staat ist das »In Form sein« einer durch ihn gebildeten und dargestellten völkischen Einheit für wirkliche und mögliche Kriege. Ist diese Form sehr stark, so besitzt sie als solche schon den Wert eines siegreichen Krieges, der ohne Waffen, nur durch das Gewicht der verfügungsbereiten Macht gewonnen wird. Ist sie schwach, so kommt sie einer beständigen Niederlage in den Beziehungen zu anderen Mächten gleich.“ [1][vi]

El Estado como „unidad de pueblos“ [völkischen Einheit] en forma –en el sentido deportivo- constituye ya, en cierto modo, una guerra ganada. Las fuerzas interiores se hayan dispuestas para la guerra victoriosa, guerra que ni siquiera llega a estallar con armas, pues es una autoridad de peso (Gewicht) la que se impone a las otras potencias. En numerosas ocasiones históricas, el pacifismo se convierte en la religión de los cansados y de los débiles. Muchas veces es, también, el intento de una potencia antaño vencedora, por imponer el status quo a los vencidos o a los postergados, y extenderlo idealmente hasta el infinito sin contestación y sin enemigos en el horizonte se hace pasar por pacifismo. Así sucede con Occidente. En un principio, su pacifismo fue el de las potencias aliadas y vencedoras sobre Alemania en las dos Guerras Mundiales. Pacifismo fue imponer el tratado de Versalles. Pacifismo también fue, en la segunda contienda, imponer la repartición del mundo en dos grandes bloques e instaurar la guerra fría. Ahora que esos dos bloques, capitalista y comunista, se han diluído y se vuelve a la política multilateral de potencias y al equilibrio entre ellas, el pacifismo es la ideología –quizá- de la masa cansada, del hombre inteligente de las grandes ciudades cosmopolitas donde se mueve de arriba a abajo un inmenso proletariado y, aún más numerosa, una gran masa de subproletarios subvencionados, mantenidos por servicios sociales y ayudas públicas. Acostumbrados, todo lo más, a la jerga de la lucha de clases pero no a la jerga de lucha de naciones, ese proletariado y subproletariado cosmopolita creciente sólo puede entender el mundo en el plano horizontal de quienes son como ellos, ajenos a lo que Spengler considera „la llamada de la sangre“. Esta masa urbana desarraigada de la tierra y de sus manantiales sanguíneos, que quedan muy remotos, es siempre antinacionalista. En el caso de abrazar una ideología nacionalista ésta no se vive ni se siente como idea, en el sentido explicitado más arriba, sino como ideal.

El Estado como „unidad de pueblos“ [völkischen Einheit] en forma –en el sentido deportivo- constituye ya, en cierto modo, una guerra ganada. Las fuerzas interiores se hayan dispuestas para la guerra victoriosa, guerra que ni siquiera llega a estallar con armas, pues es una autoridad de peso (Gewicht) la que se impone a las otras potencias. En numerosas ocasiones históricas, el pacifismo se convierte en la religión de los cansados y de los débiles. Muchas veces es, también, el intento de una potencia antaño vencedora, por imponer el status quo a los vencidos o a los postergados, y extenderlo idealmente hasta el infinito sin contestación y sin enemigos en el horizonte se hace pasar por pacifismo. Así sucede con Occidente. En un principio, su pacifismo fue el de las potencias aliadas y vencedoras sobre Alemania en las dos Guerras Mundiales. Pacifismo fue imponer el tratado de Versalles. Pacifismo también fue, en la segunda contienda, imponer la repartición del mundo en dos grandes bloques e instaurar la guerra fría. Ahora que esos dos bloques, capitalista y comunista, se han diluído y se vuelve a la política multilateral de potencias y al equilibrio entre ellas, el pacifismo es la ideología –quizá- de la masa cansada, del hombre inteligente de las grandes ciudades cosmopolitas donde se mueve de arriba a abajo un inmenso proletariado y, aún más numerosa, una gran masa de subproletarios subvencionados, mantenidos por servicios sociales y ayudas públicas. Acostumbrados, todo lo más, a la jerga de la lucha de clases pero no a la jerga de lucha de naciones, ese proletariado y subproletariado cosmopolita creciente sólo puede entender el mundo en el plano horizontal de quienes son como ellos, ajenos a lo que Spengler considera „la llamada de la sangre“. Esta masa urbana desarraigada de la tierra y de sus manantiales sanguíneos, que quedan muy remotos, es siempre antinacionalista. En el caso de abrazar una ideología nacionalista ésta no se vive ni se siente como idea, en el sentido explicitado más arriba, sino como ideal.

El Estado del pueblo persigue siempre, hacia el interior, una Economía Productiva, que le haga sólido, fuerte y capaz de una Acción Exterior: asegurarse un espacio entre enemigos. Por el contrario, el Estado plutocrático fomenta las tendencias anarquizantes en la medida en que el afán particularista de ganancia sea satisfecho, y para ello la manipulación de las grandes masas urbanas, proletarias y subproletarias, se hace esencial. No importa nada que los funcionarios, los pequeños productores, los campesinos, etc., sean los que realmente sostengan la estructura gigante: al Estado plutocrático le conviene difuminar la realidad de que son éstos sectores los que realmente hacen que se paguen las cuentas que los especuladores financieros no quieren, por principio, pagar. El complemento necesario de los saqueadores de las finanzas que se han adueñado del Estado, hasta el punto de arrebatarle toda soberanía, es el endiosamiento de un supuesto proletariado sindicalizado y mimado por mil y una ventajas, entre las que se cuentan los liberados sindicales, la invención de puestos de trabajo ad hoc, subvenciones y prebendas no basadas en el mérito sino en la fidelidad partidista o sindical, etc. En realidad el contingente de trabajadores reales que viven al margen de este clientelismo partidista o sindical no conoce ninguna de estas ventajas del proletariado ficticio. Viven en condiciones de explotación que naide cacarea públicamente y apenas se reconocen en la forma de vida y pensamiento de aquellos que dicen ser sus defensores. En realidad, los más ardientes defensores de los valores „progresistas“ (una vez que el socialismo o el comunismo, como ideologías previas a la Guerra Fría se han eclipsado) son irreconocibles en Europa, no son obreros en sentido estricto: son hijos de la clase media, profesionales liberales, „intelectuales“, productos de la gran ciudad desarraigada que buscan en el trabajador un molde en el que llenar en realidad sus tendencias anarquizantes. En ningún momento desearían organizar un Estado fuerte, militarizado, compacto, como en su día lo protendío la URSS. El Estado en manos de plutócratas fomenta sus tendencias anarquizantes pues así no hay apenas un Pueblo que presente resistencia a su saqueo constante, a su explotación:

„Esta alianza entre la Bolsa y el sindicato subsiste hoy como entonces. Está basada en la evolución natural de tales épocas, porque surge del odio común contra la autoridad del Estado y contra los directores de la economía productora, que se oponen a la tendencia anarquista a ganar dinero sin esfuerzo“ [1][vii].

Dieses Bündnis zwischen Börse und Gewerkschaft besteht heute wie damals. Es liegt in der natürlichen Entwicklung solcher Zeiten begründet, weil es dem gemeinsamen Haß gegen staatliche Autorität und gegen die Führer der produktiven Wirtschaft entspringt, welche der anarchischen Tendenz auf Gelderwerb ohne Anstrengung im Wege stehen. [1][viii]

Si analizamos el comportamiento de las fuerzas gobernantes en Europa, y muy señaladamente en España, vemos que –pese a los discursos- la tendencia ha sido siempre desmantelar todos aquellos núcleos de economía productiva [produktiven Wirtschaft]. El capital especulativo no tolera la existencia de una sociedad civil independiente de sus manejos, como puede ser la sociedad rural. Allí donde millones de personas –de manera esforzada y austera- viven del cultivo de sus propias tierras y del cuidado de sus ganaderías, con un sentido ancestral de la propiedad, que no es el sentido „romano“ o absolutista de propiedad, el capital especulativo –con la mirada complaciente de las grandes centrales sindicales obreras- entra arrasando, ávido de esclavizar y proletarizar esas masas de población hasta ayer libres. El abandono generalizado del campo español, y muy especialmente la muerte demográfica del Noroeste de la Península Iberica guarda un relación íntima con esta alianza entre la Bolsa y el Sindicato. A la masa, desde hace décadas, se le inculca la falsa –pero interesada- idea de que se puede vivir sin trabajar, que es posible una vida muelle llena de lujos y comodidades en todo punto incompatible con la tradicional existencia en el campo, llena de abnegación y esfuerzo, pero también de amor hacia la tierra, hacia el caserío, hacia la familia y hacia todo cuanto se obra.

3. El Democratismo y su guerra contra la Tradición.

El democratismo es inherente a una sociedad de comunicación de masas, donde existen aparatos de propaganda y la posibilidad urbana de que puedan ser alzados líderes y portavoces del „pueblo“, entendida la palabra „pueblo“ en el sentido de los revolucionarios desde 1789: los „ciudadanos“ que concentrándose en las calles, con urnas o con guillotinas, dicen ser „nación“. Mas ya hemos visto arriba que hay un sentido previo y mucho más viejo de nación. Todavía hoy, en aquellas regiones de Europa donde sigue con vida un cierto despojo de la tradición campesina, contrasta vivamente a quien lo quiera ver el sentido de la sangre y de la tierra que posee el „paisano“ frente al „ciudadano“. Al paisano, al hijo de la propia tierra, le resultarán siempre extrañas las consignas de los líderes de masas, los jeroglíficos ideológicos que le hablan de „lucha de clases“, „proletariado universal“, „soberanía popular“, etc. Solamente sucumbe a tales consignas cuando se desarraiga, emigra a la ciudad, pierde sus raices y pisa el asfalto nivelador que cubre la verde pradera. Todos entonces, como proletarios, se sienten nivelados como proletarios y desean „gobernarse por sí mismos“. En el caso de surgir un nacionalismo con apoyo proletario, éste ha de consistir en un nacionalismo donde ha operado una sustitución del pueblo por la masa-

„El nacionalismo moderno sustituye el pueblo por la masa. Es revolucionario y urbano de parte a parte“[1][ix] .

„Der moderne Nationalismus ersetzt das Volk durch die Masse. Er ist revolutionär und städtisch durch und durch.“.[1][x]

En la sociedad de masas los líderes invocan al Pueblo, y a la masa que está dejando de ser Pueblo se le intenta convencer del derecho a gobernarse por sí misma. En realidad hay ya toda una casta de „representantes del pueblo“ que viven a costa de él, casta parasitaria y hostil al trabajo, la cúpula de los políticos profesionales y aun de los revolucionarios profesionales. Se sirven del pueblo, y lo azuzan sirviéndose de los elementos más manipulables y agresivos de la chusma para conducir al rebaño. La oclocracia es el complemento perfecto para los especuladores de la Bolsa, para los depredadores financieros. Hace falta una sociedad desorganizada y cada vez más dependiente, para que los empleados al servicio del capital agiten y conduzcan a las masas. Los partidos de masas se vuelven máquinas engrasadas y sostenidas por bancos y empresas particulares, detrás de cada pancarta seguida por millones, hay millones de dólares o de euros. Incluso los que dicen ser „anticapitalistas“ y convocan –puntualmente- a millones de seguidores, son con frecuencia unos mercenarios que han conseguido auparse haciendo la labor del carnicero: despiezar el cuerpo social para que tan suculento alimento llene las bolsas insaciables del Capital.

En la sociedad de masas los líderes invocan al Pueblo, y a la masa que está dejando de ser Pueblo se le intenta convencer del derecho a gobernarse por sí misma. En realidad hay ya toda una casta de „representantes del pueblo“ que viven a costa de él, casta parasitaria y hostil al trabajo, la cúpula de los políticos profesionales y aun de los revolucionarios profesionales. Se sirven del pueblo, y lo azuzan sirviéndose de los elementos más manipulables y agresivos de la chusma para conducir al rebaño. La oclocracia es el complemento perfecto para los especuladores de la Bolsa, para los depredadores financieros. Hace falta una sociedad desorganizada y cada vez más dependiente, para que los empleados al servicio del capital agiten y conduzcan a las masas. Los partidos de masas se vuelven máquinas engrasadas y sostenidas por bancos y empresas particulares, detrás de cada pancarta seguida por millones, hay millones de dólares o de euros. Incluso los que dicen ser „anticapitalistas“ y convocan –puntualmente- a millones de seguidores, son con frecuencia unos mercenarios que han conseguido auparse haciendo la labor del carnicero: despiezar el cuerpo social para que tan suculento alimento llene las bolsas insaciables del Capital.

„Lo más funesto es el ideal del gobierno del pueblo „por sí mismo“. Un pueblo no puede gobernarse a sí mismo, como tampoco mandarse a sí mismo un ejército. Tiene que ser gobernado, y así lo quiere también mientras posee instintos sanos. Pero lo que con ello se quiere decir es cosa muy distinta: el concepto de representación popular desempeña inmediatamente el papel principal en cada uno de tales movimientos. Llegan gentes que se nombran a sí mismas „representantes“ del pueblo y se recomiendan como tales. Pero no quieren „sevir al pueblo“; lo que quieren es servirse del pueblo para fines propios, más o menos sucios, entre los cuales la satisfacción de la vanidad es el más inocente“. [1][xi]

“Am verhängnisvollsten ist das Ideal der Regierung des Volkes »durch sich selbst«. Aber ein Volk kann sich nicht selbst regieren, so wenig eine Armee sich selber führen kann. Es muß regiert werden und es will das auch, solange es gesunde Instinkte besitzt. Aber es ist etwas ganz anderes gemeint: der Begriff der Volksvertretung spielt in jeder solchen Bewegung sofort die erste Rolle. Da kommen die Leute, die sich selbst zu »Vertretern« des Volkes ernennen und als solche empfehlen. Sie wollen gar nicht »dem Volke dienen«; sich des Volkes bedienen wollen sie, zu eigenen, mehr oder weniger schmutzigen Zwecken, unter denen die Befriedigung der Eitelkeit der harmloseste ist“. [1][xii]

Encontramos en estas líneas una crítica implacable al concepto de Democracia. En realidad, siempre se trata de una manipulación por parte de las masas. Y ¿quién manipula? Esas „gentes que llegan“ arrogándose la representación del Todo, sea cual sea su orígen. Esas gentes mercenarias, que luchan contra la Tradición en cuanto ésta es una forma de Cultura. El afán por presentar la Tradición como una losa represiva y un grillete a la libertad es la tónica común en estos lídes oclocráticos. Nunca se quiere ver en la Tradición la musculatura y la médula de una Cultura aún digna y viva, un poso de antiguas libertades conquistadas. Se propaga el principio fanático de erosionar la Autoridad donde quiera y cuando quiera: los niños que empiezan tuteando al maestro y terminan por insultarle y agredirle, la chanza periodística hacia los sacerdotes que culmina en la quema de iglesias con ellos dentro, la sorna del intelectual dirigida contra el matrimonio unido, con vocación de teenr hijos que acaba convirtiéndose en destrucción y sustitución étnicas y en degradación de la infancia...Los líderes oclocráticos potencian las tendencias anarquizantes y aun diríamos la tendencia entrópica de las sociedades. El nihilismo es inherente a sus prédicas. Destruir y aniquilar lo forjado durante siglos, y presentar todo el proceso disolutorio como proceso emancipador.

„Combaten a los poderes de la tradición para ocupar su lugar. Combaten el orden del Estado porque impide su peculiar actividad. Combaten toda clase de autoridad porque ni quieren ser responsables ante nadie y eluden por sí mismos toda responsabilidad. Ninguna constitución contiene una instancia ante la cual tengan que justificarse los partidos. Combaten, sobre todo, la forma de cultura del Estado, lentamente crecida y madurada, porque no la entrañan en sí, como la buena sociedad, la society del siglo XVIII, y la sienten, por lo tanto, como una coerción, lo cual no es para el hombre de cultura. De este modo nace la „democracia“ del siglo, que no es forma sino ausencia de forma en todo sentido, como principio, y nacen el parlamentarismo como anarquía constitucional y la república como negación de toda clase de autoridad“ [1][xiii].

„Sie bekämpfen die Mächte der Tradition, um sich an ihre Stelle zu setzen. Sie bekämpfen die Staatsordnung, weil sie ihre Art von Tätigkeit hindert. Sie bekämpfen jede Art von Autorität, weil sie niemandem verantwortlich sein wollen und selbst jeder Verantwortung aus dem Wege gehen. Keine Verfassung enthält eine Instanz, vor welcher die Parteien sich zu rechtfertigen hätten. Sie bekämpfen vor allem die langsam herangewachsene und gereifte Kulturform des Staates, weil sie sie nicht in sich haben wie die gute Gesellschaft, die society des 18. Jahrhunderts, und sie deshalb als Zwang empfinden, was sie für Kulturmenschen nicht ist. So entsteht die »Demokratie« des Jahrhunderts, keine Form, sondern die Formlosigkeit in jedem Sinne als Prinzip, der Parlamentarismus als verfassungsmäßige Anarchie, die Republik als Verneinung jeder Art von Autorität.“ [1][xiv]

La forma de la Cultura que posee un Estado (Kulturform) es un lento resultado de desarrollo orgánico, que exige una maduración (gereifen) y un enraizamiento (angewachsen). Recordemos que el autor de La Decadencia de Occidente sostenía ya, en su magna obra, que las culturas son como plantas, que exigen un enraizamiento. Los pueblos dotados de un alma única hunden sus raíces en un territorio y dejan afluir sus torrentes de sangre a lo largo de las generaciones, llegando a asomar en la Historia por medio de sus realizaciones. Los pueblos de Europa crearon los diversos Estados como creaciones dinásticas de sus príncipes y de sus noblezas, adquiriendo cada uno de ellos una estructura formal y un punto máximo de rendimiento y plenitud, y sólo con el socavamiento del Principio de Autoridad (primero Rousseau, después Robespierre) comenzó su curva a declinar.

El estilo estentóreo y sangriento de hacer política viene de Francia: es el estilo de la Revolución. A pesar de que ya no existen fuerzas políticas revolucionarias dignas de consideración, y a pesar de que los partidos comunistas o socialistas en Europa sólo aspiran a ganar las elecciones, a ocupar los cargos con sus gentes y a ayudar a los plutócratas a mantener el staus quo, toda el lenguaje y los gestos se han heredado de aquel periodo de las revoluciones. Incluso al Parlamento se llevan las arengas, los carteles y las pancartas, confundiendo ámbitos, el ámbito de la lucha callejera y el ámbito de la asamblea parlamentaria. La norma es „no respetar para ganar“. Solo ganar: la erosión del principio del Respeto, el no reconocimiento de la Autoridad, es el fondo anarquizante que llevan consigo los partidos y los sindicatos. Como consecuencia de haber asumido un marxismo „cultural“, difuso o atmosférico (con poca relación con la obra de Marx, obra sólo conocida por algunos académicos), el Estado, las instituciones, las reglas del juego, la Constitución, los símbolos, la Corona, todo, absolutamente todo es objeto de posible manipulación, susceptible de convertirse en instrumento para una „lucha civil“. Pero no se piense que es la pugna de una clase proletaria contra las clases dominantes. Se trata de la lucha de aquellos grupos sociales deseosos de vivir sin trabajar, frecuentemente alimentados por un Poder financiero, contra otros grupos que, en base a su propio sudor, pretenden defender una meritocracia, esto es, una genuina Aristocracia.

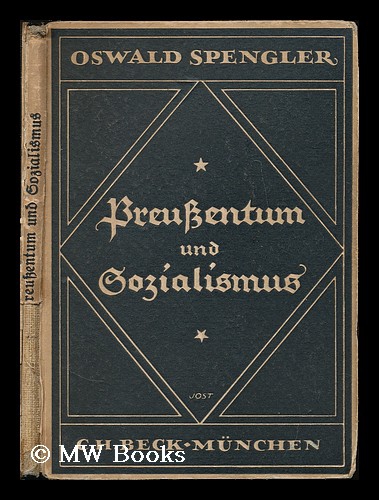

4. Socialismo prusiano.

Aristocracia es, literalmente, el Poder de los Mejores. En un sistema productivo en el que los grupos mediocres y hostiles al trabajo pretenden ganar posiciones y convertirse en pensionados de la parte productiva de la sociedad, la Aristocracia se convierte en un régimen odiado a muerte. No se reconoce el derecho a ser persona de mérito. Es odiado quien consigue una fortuna –pequeña o grande- por su esfuerzo o habilidad: sólo se ve que posee más. Es odiado quien saca una plaza de funcionario tras una dura preparación: sólo se ven privilegios en su cargo. Es odiado quien sigue con raíces en su terruño, conservando la dignidad de su caserío: es un atraso y una afrenta a la sociedad urbana y cosmopolita. Es odiado, en fin, el obrero que trabaja duro cada día y que no sigue las consignas y los eslóganes de sus supuestos tuteladores, los obreros liberados y los funcionarios de la central sindical: es un esquirol, pues además anhela con dejar de ser proletario, establecerse por su cuenta, mejorar de posición social. Para el obrerismo, la mejor condición del hombre es convertirse en obrero, „el héroe de nuestro tiempo“, como decía Spengler. Quien desea cambiar de clase es un traidor. El marxismo ha degenerado en obrerismo desde el principio, traicionando los propósitos de su fundador, que no era un obrero y que concibió muy vagamente el comunismo como una generalización del Principio del Trabajo („de cada uno según sus capacidades...“), pero no una nivelación obrerista. En realidad, el absurdo despótico de Mao Tse-Tung de mandar a los médicos, a los abogados y a los profesores chinos a trabajar en los arrozales está más cerca del marxismo „cultural“ o vulgar y del democratismo europeos, que del socialismo. Se trata de una nivelación absoluta, de un odio hacia la diferencia intelectual existente entre las personas. Una nostalgia de los tiempos salvajes. El socialismo, tal y como lo entiende Oswald Spengler, no consiste en una uniformización de todos los individuos, en un colectivismo absoluto. El socialismo consiste en erigir un Estado en forma de cuerpo orgánico. Se trata de un Estado total, que no totalitario, el cual habrá de agrupar a los distintos órganos productivos, profesionales, territoriales, y en el que cada uno de ellos velará por un estricto mantenimiento de su identidad, pero a la vez, por un sometimiento a lo superior. El socialismo no puede ser el mismo en cada pueblo, y el socialismo „prusiano“ estaba llamado, a su entender, a cumplir una alta misión:

„[...] el estilo prusiano es una renuncia por libre decisión, el doblegarse de un vigoroso yo ante un gran deber y una gran misión, un acto de dominio de sí mismo, y en este sentido el máxismo individualismo de que el presente es capaz.

La „raza“ celtogermánica es la de más fuerte voluntad que jamás viera el mundo. Pero este „¡quiero!“ –Yo quiero!, que llena hasta los bordes el alma faústica en el pensamiento, la acción y la conducta, despertaba la conciencia de la absoluta soledad del yo en el espacio infinito“.[1][xv]

„Aber der preußische Stil ist ein Entsagen aus freiem Entschluß, das Sichbeugen eines starken Ichs vor einer großen Pflicht und Aufgabe, ein Akt der Selbstbeherrschung und insofern das Höchste an Individualismus, was der Gegenwart möglich ist.

Die keltisch-germanische »Rasse« ist die willensstärkste, welche die Welt gesehen hat. Aber dies »Ich will« – Ich will! –, das die faustische Seele bis an den Rand erfüllt, den letzten Sinn ihres Daseins ausmacht und jeden Ausdruck der faustischen Kultur in Denken, Tun, Bilden und Sichverhalten beherrscht, weckte das Bewußtsein der vollkommenen Einsamkeit des Ichs im unendlichen Raum.“. [1][xvi]

Convertirse en señores de sí mismos, el autodominio (Selbstbeherrschung): he aquí la clave del Socialismo „Prusiano“. Solo obedece con grandeza quien posee un yo musculoso, pleno de fuerza. En estas densas líneas resuena Nietzsche, pero transformado por el nacionalismo alemán, ausente en éste filósofo, lo que es una gran diferencia respecto a Spengler. Al extender una nacionalidad concreta en el sentido moderno (prusiana, alemana) a categorías etnológicas pre y protohistóricas („raza“ celto-germana), Spengler lleva a cabo, sin explicitarla, una operación de vasta mirada hacia atrás para así también poder ver lejos y hacia adelante. Realmente, el autor de La Decadencia de Occidente es un gran filósofo de la Historia. Y la Historia no ha de ser vista como una masa uniforme de hechos dentro de los cuales el científico ha de rastrear causas, al estilo de las causas mecánicas, que anteceden la sucesión temporal de los hechos. Este método se lo cede nuestro filósofo a los positivistas, evolucionistas y materialistas históricos, pues parientes son entre sí, hijos del siglo XIX, el siglo desastroso en que la Cultura Europea deviene Civilización cansada, vieja, siglo en que comienza el proceso morboso de todo ser envejecido. El envejecimiento comienza con la multiplicación ingente de masas desarraigadas, de subproletarios que ignoran ya todo cuanto tenga que ver con la patria, la tradición, la sangre, el suelo. Cada individuo de esa masa ingente se autoconcibe él mismo como un átomo, y la sociedad de consumo de masas pugna en todo momento por que esta autoconcepción del sujeto responda a la realidad. Para ello, es una prioridad fundamental en el sistema de masas, ya sea el capitalista ya sea el bolchevique, provocar una debilitación progresivas de la Voluntad, el Entendimiento y la capacidad de Atención.

5. Voluntad y Tradición

Debilitar la Voluntad de pueblos primitivos o salvajes, es tarea relativamente sencilla, pues cualquier individuo o institución dotados de „mana“, de fuerza mágica intrínseca, les doblega. Otra cosa sucede con los pueblos europeos. En ellos, el concepto de persona y más aún, el concepto de sujeto entendido como centro de fuerzas volitivas que pugnan por imperar, por afirmarse, ha tenido su más alta expresión. Frente a las demás „razas“ (recuérdese que en Spengler la palabra adquiere un sentido espiritual y no biológico), la raza celtogermánicase aparece como la más fuerte en cuenta voluntad [Die keltisch-germanische »Rasse« ist die willensstärkste, welche die Welt gesehen hat]y esto se refleja en su derecho personalista (frente al derecho puntiforme y meramente corpóreo de los romanos), en su concepto de lealtad (frente al despotismo del yo y su derecho de “uso y abuso” sobre las cosas). Esa raza celtogermánica, parcialmente sometida o colonizada bajo el Imperio de Roma, habría de renacer –ya con las ventajas de asimilarse una idea Imperial y una cultura superior- al caer Roma como concreción, mas no como ideal de Imperio mundial. Su especialísima manera de entender el Derecho y la relación con la Naturaleza, la sitúa en antítesis con el romanismo tardoantiguo. Todavía hoy, es plástica esa antítesis natural entre la España Atlántica y la España Mediterránea, la Italia del Norte y la del Sur. Se trata del concepto y uso que se tiene de la Tierra mientras se conserva la fuerza de la sangre y los individuos no se han visto del todo urbanizados. En el norte, al más puro estilo celtogermánico, la tierra y la heredad están ahí para cuidar de ellas, para habitarlas, para hacer de ellas morada donde echar raíces. En el sur, bajo el derecho romano y el despotismo del yo, la tierra o la heredad se asimilan mucho más fácilmente a la mercancía, a la cosa de usar y tirar.

Pero en toda Europa asistimos a una debilitación sistemática de esa Voluntad antaño fuerte, así como también una disminución de la capacidad de Entendimiento y la de Atención. Al constituirse Europa toda en una sociedad de masas, regida de manera oclocrática y según los designios de oscuros poderes financieros, especulativos, se ha ido generando todo un sistema educativo para las masas que, en realidad, consiste en una neutralización de sus fuerzas volitivas. Las sucesivas reformas educativas van encaminadas a la eliminación de esas fuerzas, a disociar el esfuerzo y el conocimiento, a facilitar la integración del niño y del joven en una sociedad pasiva de consumidores, apenas capaces de otra cosa que de buscar la evasión. Evadirse por medio del alcohol, las drogas y los artefactos tecnológicos: esa es la única motivación de unas generaciones hostiles al trabajo, abúlicas y sin capacidad ninguna para la escucha. Pues la falta de Atención es la gran enfermedad de Europa, del “mundo desarrollado”. Nadie escucha: entre el ruido informativo, un mensaje relevante queda sepultado, neutralizado, y cuando accede a alguna conciencia dentro de márgenes minoritarios, ese mensaje es sometido al escarnio sistemático. Dentro del ruido informativo que se precisa en una sociedad de masas ha de figurar en todo momento un apretado pelotón de “progresistas” encargado de hacer mofa de todo cuanto ha sido tradición, salud, cultura. Ya no hace falta esfuerzo para ser sabio, ya no es menester tener hijos y cuidarlos, ya no importa el decoro de la vida privada ni conductas nobles y recatadas. Todo se ha de sacrificar en el altar del Progreso hasta que por fin se banalice por completo el concepto de persona y sus extensiones: privacidad, sexualidad, propiedad. En cierto modo el pelotón ruidoso del “Progresismo” desea, sin cambiar una coma del dictado capitalista financiero, sin rozarle un pelo al modo de producción-saqueo vigente, una realización quintaesenciada del comunismo: desaparición de la privacidad (a la que contribuyen las nuevas tecnologías, Internet, etc.), prostitución generalizada (el sexo como mercancía a ofrecer y a tomar por parte de todos), y banalización de la propiedad (incesante retirada de escena de la Propiedad productiva a favor de la propiedad abstracta, reducción a la condición de “mercancía”).

Mientras este proceso se acelera, y se crea masas “sin raza”, debidamente mezcladas y desarraigadas en las grandes ciudades, al principio, a la par que se despuebla y degrada el campo, acontecen determinados procesos de aculturación y sustitución étnica. De manera similar a la decadencia del Imperio Romano, el Imperio de Europa declina al convertirse la ciudadanía en una mera expresión formal que abarcaba a gentes muy diversas, arrancadas violentamente o por grado de sus terruños, con modos de vida ya sincréticos, mezcla de indigenismo y romanismo. De la misma manera, esta Europa llena de mezquitas y de frenéticos bailes negroides, ya no es la Europa del gótico, ni la de Bach, Mozart o Beethoven. La cultura del nativo, que hasta ayer se vio como Cultura Superior, es hoy cultura del civilizado europeo cansado, dispuesto a pagar mercenarios para defenderse y para que le traigan el pan a casa. El cansado nativo de Europa ya le da la espalda a Cervantes o a Shakespeare. Siente vergüenza de Wagner o de Leibniz. Rechaza a Homero o a Lord Byron. Se arranca de la piel su ser y su esencia y quisiera ser “otro”, en un proceso de alienación y masoquismo interminable. Todas las glorias de la cultura de Occidente se arrojan al vertedero de los trastos viejos, e incluso se destruyen conscientemente en el medio educativo por temor a la ofensa de ese “otro” al que se dice –hipócritamente- respetar. En los mismos centros educativos españoles de los que está despareciendo el griego y el latín, se introduce gradualmente el árabe. Allí donde se condena inquisitorialmente a Nietzsche o a Wagner, se practica el tatuaje y la danza del vientre. Para que el sistema capitalista tardío funcione es preciso cometer este atentado contra las raíces. De lo contrario sería imposible contar con masas de consumidores-colaboradores, no habría posibilidad de reclutar más y más adeptos. El verdadero respeto al “otro” nunca es sincero si implica una renuncia a lo propio. El verdadero respeto consiste en la aceptación de las diferencias, en la asunción de un pluralismo cultural, en la crítica de la idea monolítica y absoluta de “Humanidad”. Que cada cultura o civilización se mueva en su propio ámbito y gire en torno a su eje, aprendiendo de las demás pero no mezclándose con ellas: en esto ha de consistir el respeto intercultural.

[i][i] Oswald Spengler: Años Decisivos. Alemania y la Evolución Histórica Universal. Espasa-Calpe, Madrid, 1982. Traducción de Luis López-Ballesteros; p. 47.

[i][ii] La versión alemana de Años Decisivos por la que citamos es: Oswald Spengler: Jahre der Entscheidung.Deutschland und die weltgeschichtliche Entwicklung, Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich, 1961; p. 50-51.

[i][iii]Años Decisivos, p. 46.

[i][iv]Jahre der Entscheidung,pps. 49-50.

[i][v]Años Decisivos, pps. 45-46

[i] [vii] Años Decisivos, p. 88.

[i][ix]Años Decisivos, p. 48.

[i][xi]Años Decisivos, p. 48.

[i][xiii]Años Decisivos 48-49.

[xv] Años Decisivos, 182.

[i][xvi]Jahre, p. 158.

La Razón Histórica, nº21, 2013 [69-89], ISSN 1989-2659. © Instituto de Estudios Históricos y sociales.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

La même constatation d’une situation de relative déshérence historiographique et surtout de la priorité donnée au choix de coupures par périodes (Renaissance, XVIIe siècle) peut être constatée pour ce qui est de la recherche anglo-saxonne, après les deux volumes de l’History of Europe de H. A. L. Fisher (Londres, 1935). Citons l’exemple de la Short Oxford History of Europe qui, si elle est récente, n’en est pas moins très traditionnelle dans sa conception clivant le passé en grandes séquences classiques si ce n’est anachronisantes, à commencer par « Classical Greece » ou « Roman Europe » ; citons aussi, plus originales, les New Approaches to European History de Cambridge Uni- versity Press et les Fontana History of Europe Series qui reposent sur un projet thématico-chronologique. À quoi s’ajoute The Penguin History of Europe, de J. M. Roberts (1996), fort heureusement renouvelée dans les Penguin History of Europe Series grâce aux contributions de grands spécialistes comme Chris Wickham ou Mark Greengrass. Là est le paradoxe, c’est la Grande-Bretagne du Brexit d’aujourd’hui qui a donné récemment les ouvrages scientifiques les plus parachevés sur une Europe désanachronisée et pensée comme une totalité d’histoire ayant fonctionné plus sur des connexions que sur des spécificités ou sur des collections de particularités. Pour aller dans cette direction, l’histoire de l’Europe se trouve travaillée outre-Manche surtout systématiquement sur le plan de l’histoire économique, avec The Cambridge Economic History of Europe et The Fontana Economic History of Europe. Un peu à part, original, et soupçonné aujourd’hui d’européo-centrisme parce que donnant le primat à la question de l’exceptionnalité du continent désormais passé de mode, il y a le livre important d’Eric Jones, The European Miracle (Cambridge, 1981) à l’inverse du plus superficiel Europe. A History, de Norman Davies (Oxford, 1996). Il faudrait signaler encore Eugen Weber et Une histoire de l’Europe, Paris (2 vol., Paris, 1986-1987), qui insiste sur le concept postromantique d’héritage légué au monde mais noie le lecteur sous une avalanche factuelle donnant une certaine invisibilité à l’objet même Europe.

La même constatation d’une situation de relative déshérence historiographique et surtout de la priorité donnée au choix de coupures par périodes (Renaissance, XVIIe siècle) peut être constatée pour ce qui est de la recherche anglo-saxonne, après les deux volumes de l’History of Europe de H. A. L. Fisher (Londres, 1935). Citons l’exemple de la Short Oxford History of Europe qui, si elle est récente, n’en est pas moins très traditionnelle dans sa conception clivant le passé en grandes séquences classiques si ce n’est anachronisantes, à commencer par « Classical Greece » ou « Roman Europe » ; citons aussi, plus originales, les New Approaches to European History de Cambridge Uni- versity Press et les Fontana History of Europe Series qui reposent sur un projet thématico-chronologique. À quoi s’ajoute The Penguin History of Europe, de J. M. Roberts (1996), fort heureusement renouvelée dans les Penguin History of Europe Series grâce aux contributions de grands spécialistes comme Chris Wickham ou Mark Greengrass. Là est le paradoxe, c’est la Grande-Bretagne du Brexit d’aujourd’hui qui a donné récemment les ouvrages scientifiques les plus parachevés sur une Europe désanachronisée et pensée comme une totalité d’histoire ayant fonctionné plus sur des connexions que sur des spécificités ou sur des collections de particularités. Pour aller dans cette direction, l’histoire de l’Europe se trouve travaillée outre-Manche surtout systématiquement sur le plan de l’histoire économique, avec The Cambridge Economic History of Europe et The Fontana Economic History of Europe. Un peu à part, original, et soupçonné aujourd’hui d’européo-centrisme parce que donnant le primat à la question de l’exceptionnalité du continent désormais passé de mode, il y a le livre important d’Eric Jones, The European Miracle (Cambridge, 1981) à l’inverse du plus superficiel Europe. A History, de Norman Davies (Oxford, 1996). Il faudrait signaler encore Eugen Weber et Une histoire de l’Europe, Paris (2 vol., Paris, 1986-1987), qui insiste sur le concept postromantique d’héritage légué au monde mais noie le lecteur sous une avalanche factuelle donnant une certaine invisibilité à l’objet même Europe. On peut, entre autres travaux individuels ou collectifs, ajouter à cette sphère d’écriture Krzysztof Pomian, L’Europe et ses nations (Paris, 1990), puis Jacques Le Goff, La Vieille Europe et la nôtre (Paris, 1994) ou L’Europe est-elle née au Moyen Âge ? (Paris, Seuil, 2003). L’ouvrage de Denis de Rougemont, Vingt-huit siècles de l’Europe, la conscience européenne à travers les textes d’Hésiode à nos jours (Paris, 1961), est un produit militant issu de la réflexion de l’un des fondateurs du projet européen de l’après-1945. Notons encore Identités nationales et conscience européenne, sous la direction de Joseph Rovan et Gilbert Krebs (Paris, 1992). Et encore, L’Europe dans son histoire. La vision d’Alphonse Dupront, publié par François Crouzet et François Furet (Paris, 1998). Ou Penser l’Europe, d’Edgar Morin (Paris, 1987), qui met l’accent sur la complexité européenne, et sur le dialogue des pluralités ou l’interculturalité étant le moteur interne de l’histoire de l’Europe, « unitas multiplex ».

On peut, entre autres travaux individuels ou collectifs, ajouter à cette sphère d’écriture Krzysztof Pomian, L’Europe et ses nations (Paris, 1990), puis Jacques Le Goff, La Vieille Europe et la nôtre (Paris, 1994) ou L’Europe est-elle née au Moyen Âge ? (Paris, Seuil, 2003). L’ouvrage de Denis de Rougemont, Vingt-huit siècles de l’Europe, la conscience européenne à travers les textes d’Hésiode à nos jours (Paris, 1961), est un produit militant issu de la réflexion de l’un des fondateurs du projet européen de l’après-1945. Notons encore Identités nationales et conscience européenne, sous la direction de Joseph Rovan et Gilbert Krebs (Paris, 1992). Et encore, L’Europe dans son histoire. La vision d’Alphonse Dupront, publié par François Crouzet et François Furet (Paris, 1998). Ou Penser l’Europe, d’Edgar Morin (Paris, 1987), qui met l’accent sur la complexité européenne, et sur le dialogue des pluralités ou l’interculturalité étant le moteur interne de l’histoire de l’Europe, « unitas multiplex ». On pourrait encore évoquer le centrage sur la démographie, avec l’Histoire des populations de l’Europe éditée par Jean-Pierre Bardet et Jacques Dupaquier (3 vol., Paris, 1997), sur l’histoire de l’écosystème, avec l’Histoire de l’environnement européen de Robert Delort (préface de Jacques Le Goff, Paris, 2001). L’Europe peut encore s’écrire dans la longue durée de son histoire économique tendant vers une « unité organique » malgré ses « diversités », avec L’Histoire de l’économie européenne 1000-2000 de François Crouzet (Paris, 2000) : « On essaiera constamment de considérer l’Europe comme un ensemble, et de prêter attention aux relations entre ses diverses parties : au commerce intra-européen, qui s’est développé de bonne heure, notamment sur la base des dotations différentes en ressources de l’Europe du Nord et de celle du Sud ; à la diffusion des institutions, des organisations et des technologies, aux migrations de main-d’œuvre et de capitaux. On recherchera les forces qui ont rapproché les régions européennes et contribué à créer une économie européenne intégrée – même si ce ne fut que de façon lâche. Cependant, ni les forces centrifuges, ni les rapports avec le monde extérieur ne seront négligés… ». D’autres enquêtes se sont fixées dans la problématique de Les Racines de l’identité européenne, de Francis Dumont (Paris, 1999) ou de La Conscience européenne au XVIe siècle de Françoise Autrand et Nicole Cazauran (éd.) (Paris, 1983) ; ou dans le champ de l’histoire des relations internationales avec L’Ordre européen du XVIe au XXe siècle, dirigé par Georges-Henri Soutou (Paris, 1998) ou La Société des princes (Paris, 1999), de Lucien Bély.

On pourrait encore évoquer le centrage sur la démographie, avec l’Histoire des populations de l’Europe éditée par Jean-Pierre Bardet et Jacques Dupaquier (3 vol., Paris, 1997), sur l’histoire de l’écosystème, avec l’Histoire de l’environnement européen de Robert Delort (préface de Jacques Le Goff, Paris, 2001). L’Europe peut encore s’écrire dans la longue durée de son histoire économique tendant vers une « unité organique » malgré ses « diversités », avec L’Histoire de l’économie européenne 1000-2000 de François Crouzet (Paris, 2000) : « On essaiera constamment de considérer l’Europe comme un ensemble, et de prêter attention aux relations entre ses diverses parties : au commerce intra-européen, qui s’est développé de bonne heure, notamment sur la base des dotations différentes en ressources de l’Europe du Nord et de celle du Sud ; à la diffusion des institutions, des organisations et des technologies, aux migrations de main-d’œuvre et de capitaux. On recherchera les forces qui ont rapproché les régions européennes et contribué à créer une économie européenne intégrée – même si ce ne fut que de façon lâche. Cependant, ni les forces centrifuges, ni les rapports avec le monde extérieur ne seront négligés… ». D’autres enquêtes se sont fixées dans la problématique de Les Racines de l’identité européenne, de Francis Dumont (Paris, 1999) ou de La Conscience européenne au XVIe siècle de Françoise Autrand et Nicole Cazauran (éd.) (Paris, 1983) ; ou dans le champ de l’histoire des relations internationales avec L’Ordre européen du XVIe au XXe siècle, dirigé par Georges-Henri Soutou (Paris, 1998) ou La Société des princes (Paris, 1999), de Lucien Bély.

On peut poursuivre avec Ernst Kantorowicz et son parcours qui le mène tout d’abord de Frédéric II, empereur-sauveur, et d’un attachement à un Reich imaginé régénérateur, de la foi dans le génie de la nation allemande, au boycott de ses cours par les étudiants nazis, puis à son exfiltration d’Allemagne. Parvenu aux USA et nommé à Berkeley, il doit affronter le maccarthysme en se faisant le défenseur d’une conception européenne de l’université à laquelle il reste attaché. Et son œuvre, qui est alimentée de multiples sources puisées dans des espaces et des temps différents, Gérald Chaix l’écrit, dépasse les évidences dans un paradoxe apparent : parce que sa « perspective est d’emblée européenne, même si, dans sa lecture impériale, il attribue à une Allemagne imprégnée de romanité un destin privilégié. Elle le demeure lorsque les circonstances, mais aussi ses propres choix, l’en éloignent. Elle se précise lorsque étudiant la conception anglaise des deux corps du roi, il situe explicitement celle-ci dans la construction chronologique et géographique d’une histoire européenne nullement close sur elle-même. » Kantorowicz pense par l’Europe. L’Europe conditionne sa pensée et son inventivité d’historien.

On peut poursuivre avec Ernst Kantorowicz et son parcours qui le mène tout d’abord de Frédéric II, empereur-sauveur, et d’un attachement à un Reich imaginé régénérateur, de la foi dans le génie de la nation allemande, au boycott de ses cours par les étudiants nazis, puis à son exfiltration d’Allemagne. Parvenu aux USA et nommé à Berkeley, il doit affronter le maccarthysme en se faisant le défenseur d’une conception européenne de l’université à laquelle il reste attaché. Et son œuvre, qui est alimentée de multiples sources puisées dans des espaces et des temps différents, Gérald Chaix l’écrit, dépasse les évidences dans un paradoxe apparent : parce que sa « perspective est d’emblée européenne, même si, dans sa lecture impériale, il attribue à une Allemagne imprégnée de romanité un destin privilégié. Elle le demeure lorsque les circonstances, mais aussi ses propres choix, l’en éloignent. Elle se précise lorsque étudiant la conception anglaise des deux corps du roi, il situe explicitement celle-ci dans la construction chronologique et géographique d’une histoire européenne nullement close sur elle-même. » Kantorowicz pense par l’Europe. L’Europe conditionne sa pensée et son inventivité d’historien. Penser par l’Europe, mais aussi penser pour l’Europe. La seconde partie du livre s’attache à une autre modalité de mise en problème historique de l’Europe. Avec en ouverture bien sûr, Johan Huizinga qui traduit une volonté d’écrire une histoire de l’Europe dans la perspective d’une fin de durée, un « automne » du Moyen Âge d’abord franco-bourguignon caractérisé par une exacerbation d’affects contradictoires, l’exubérance d’une vie contrastée mais commune. Et ensuite, après les idéaux chevaleresques, il y eut les idéaux renaissants qui transcendèrent la diversité des hommes et des nations. Et Jean-Baptiste Delzant d’insister sur un point : l’Europe de Huizinga est d’abord un « esprit » transhistorique qui en appelle à un « besoin d’unité civilisatrice » et donc à une exigence morale partagée et conceptualisée, entre autres, par Érasme. L’histoire apparaît tel un bouclier, une mise en défense contre les idéologies négatives ultranationalistes, contre les ruines qui en adviennent et en sont advenues au cours du XXe siècle, et pour Huyzinga, de ce fait, elle a un avenir et un présent : « donner corps à une unité désirée… ».