On the eastern slopes of the Andes Mountains, in the remote San Martin Province of Peru, lie the abandoned ruins of a mysterious civilization. Modern Peruvians tell us that a people whom they call the Chachapoya, “the cloud people,” built these structures. The most notable of these is the massive Kuelap Fortress, which contains more stone than even the pyramid of Cheops in Egypt. The Chachapoyan civilization, which according to the carbon-14 dating method dates at least as far back as 400 AD, existed until around 1500 AD. At that time, it succumbed to two external forces that arose in short succession. First, the expanding Incan Empire, which conquered the Chachapoyan civilization around 1490 after 20 years of fierce resistance, and next, diseases that the Europeans introduced after 1492 and which started showing up among the Chachapoya around 1535, diseases to which the Chachapoya had no immunity.

The principal mystery of the Chachapoyan civilization lies in is its origin. The Chachapoyan ruins give evidence of an advanced civilization that must have required centuries to develop. Yet none of this development appears to have taken place in South America. Culturally the Chachapoyan civilization seems to have borrowed nothing from other South American civilizations and geographically the Chachapoya were not even near any of them. The Chachapoyan civilization, therefore, most likely arose in ancient times somewhere outside of South America, and then, still in ancient times, dropped down out of nowhere in Peru.

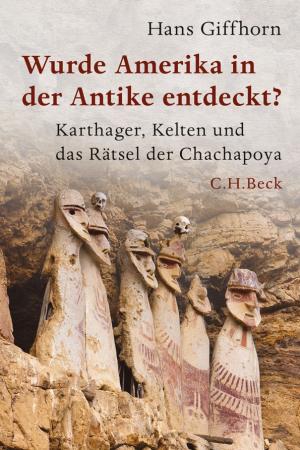

Professor Hans Giffhorn of Germany has made studying the Chachapoyan civilization his life’s work and has advanced an interesting theory regarding its origin. After many years of research starting in the 1990’s, Professor Giffhorn published a fascinating German language book in 2013 entitled Wurde Amerika in der Antike entdeckt? (“Was America discovered in antiquity?”)

Professor Hans Giffhorn of Germany has made studying the Chachapoyan civilization his life’s work and has advanced an interesting theory regarding its origin. After many years of research starting in the 1990’s, Professor Giffhorn published a fascinating German language book in 2013 entitled Wurde Amerika in der Antike entdeckt? (“Was America discovered in antiquity?”)

Professor Giffhorn draws on scientific evidence to demonstrate that the Chachapoya probably came from the Old World. Medical examinations of Chachapoyan mummies starting around ten years ago at Quinnipiac College near New Haven, Connecticut have proved that some of the Chachapoya suffered from the disease of tuberculosis. Now tuberculosis is a disease that human beings ordinarily contract from cattle. Inasmuch as there were no cattle in the New World prior to 1492, it is logical to suspect that the ancestors of the Chachapoya contracted tuberculosis somewhere in the Old World where cattle were present and then brought the tuberculosis with them to South America.

Professor Giffhorn draws on cultural evidence to pinpoint Europe in general and the Mediterranean Sea in particular as the specific region in the Old World where the Chachapoyan civilization most likely arose. Giffhorn drew this conclusion after noting many similarities between the Chachapoyan civilization and two civilizations of ancient Europe, the Carthaginian civilization of the Balearic Islands in the western Mediterranean Sea and the Keltic civilization of northern Spain. Among these are similarities in burial customs, religion, art, pottery, and the weaving of textiles. There are several pieces of evidence, however, that deserve special mention.

First, both the ancient Kelts and the Chachapoya kept the skulls of enemies that they had defeated in battle and then publicly displayed these skulls in and around their homes and other buildings. Moreover, both the Kelts and the Chachapoya customarily drilled holes in these skulls using an unusual technique requiring the use of conical drills.

Secondly, both the Chachapoya of Peru and the Kelts of ancient Spain customarily built round buildings out of stone rather than rectangular or square buildings out of wood, as was the custom throughout most of pre-Columbian South America. Separate teams of archeologists have reconstructed both sets of round stone buildings, and, as is obvious even from their photographs in Professor Giffhorn’s book, they are almost identical, in spite of the fact that the European and South American teams of archeologists were unaware of each other until after they had completed their reconstructions.

Thirdly, the Chachapoya used slingshots as military weapons. Moreover, the slingshots used by the Chachapoya resembled in many details those used by the ancient Carthaginian warriors in the Balearic Islands. Slingshots of were common weapons throughout the ancient Mediterranean. For example, recall the Old Testament story of David and Goliath.

Professor Giffhorn tries to make sense of all of this by starting with proven facts about antiquity and then connecting them with some educated guesses. In this way he has provided a speculative but by no means impossible scenario that traces the migration of certain ancient peoples all the way from Europe to Peru.

It is known that the ancient Carthaginians were bold explorers who, starting roughly around 700 BC, mounted a series of maritime expeditions that started from the Mediterranean Sea, passed through the Straits of Gibraltar into the Atlantic Ocean, and then sailed a long way down the coast of Africa. Their Mediterranean neighbors, including even the Romans, had little interest in exploring the Atlantic Ocean, partly out of superstitious fears of monsters and other dangers that lurked beyond Gibraltar. This gave the Carthaginians free reign to continue their explorations without interference from rivals. Moreover, there is evidence that the ancient Carthaginians not only traveled a great distance to the south but also a great distance to the west. In 1749, Carthaginian coins were discovered on the island of Corvu in the Azores Islands. The location of Corvu at the far western end of the Azores suggests that whoever left these coins had probably been traveling from west to east when they stopped at Corvu.

Two ancient writers provide some tantalizing details regarding the Carthaginians’ explorations: Diodor of Sicily, who lived about a century before Christ, and Pseudo-Aristotle, a mysterious man whose writings were included in the works of Aristotle but who was probably someone other than the famous Greek philosopher. These ancient writers tell a similar story, some of it based on the still earlier writings of Timaios of Tauromenium, Sicily (c. 345‑250 BC). According to these ancient writers, around 400 BC Carthaginian explorers sailing along the coast of Africa lost control of their ships during a fierce storm and eventually landed far to the west on what they called the “Great Island.” Now the Carthaginians’ main interest had always been in trade, but they saw no possibility for developing a trading relationship with a land that they assumed to be uninhabited. So after the Carthaginians recovered from their misfortunes, they made their way back to their homeland without leaving any colonists behind. At the same time, they did at least take note of the precise location of the Great Island and carefully kept it to themselves. In the event that their Mediterranean homeland were ever overrun, the Carthaginians had a safe haven whose location only they knew and where they could start afresh without interference from any of their former neighbors.

But this still leaves open the question of just where the Carthaginians had landed. Historians have usually assumed that the Great Island was most likely Madeira, but could also have been either one of the Cape Verde Islands or one of the Canary Islands. Professor Giffhorn, however, points out that if these historians had taken the trouble to visit these islands, they might have had second thoughts before so quickly identifying any of them as the Great Island. According to the Carthaginian descriptions that have come down to us second-hand from the ancient writers, the Great Island was a bountiful land filled with navigable rivers, fruits, wild animals, wide plains, and many species of trees. By contrast, the above‑mentioned Atlantic islands were desolate islands with no navigable rivers, few plains, and not much to offer in the way of wild game, fruits, or vegetables. Most of what they do have today was imported by modern Europeans and could not have been visible to ancient explorers.

Might the Great Island have been a Caribbean island, perhaps one of those that Columbus discovered in 1492? It is not likely. According to the ancient writers, the Carthaginians reached the Great Island in far less time than would have been required to reach any of the Caribbean islands.

The only land that really fits the description of the Great Island is, surprisingly, the stretch of South American coast between what are now the Brazilian cities of Fortaleza and Recife. Now the reader might reasonably object that if the Great Island had really been northeastern Brazil, then that would imply that the Carthaginian sailors had been blown from the west coast of Africa all the way across the Atlantic Ocean to the east coast of South America. Could such a thing have been possible? As implausible as it may seem to us, this is precisely what did happen in 1500 AD to Portuguese explorer Pedro Cabral, the modern discoverer of Brazil. We should bear in mind that the eastern tip of Brazil is only about 1800 miles away from the Western Bulge of Africa, roughly the distance between New York City and Denver. Even today, objects like worn-out refrigerators tossed into the Atlantic Ocean by West Africans have been known to wash up on Brazilian beaches.

For a long time, the Carthaginian civilization thrived to the extent that the Carthaginians had no need to worry about the future of their homeland. Eventually, however, they found themselves up against a powerful new enemy in the Romans. In 146 BC, the Romans captured and destroyed the city of Carthage on the north coast of Africa in what is now the nation of Tunisia. Although the Romans had conquered Carthage, the Carthaginian colonies in the Balearic Islands continued for the time being to remain free of Roman control. But their inhabitants were undoubtedly aware of the downfall of their mother-city of Carthage and may have concluded that it was only a matter of time until they suffered the same fate. Rather than stand by and wait until their turn came, the more enterprising persons among them made plans to move permanently to the half-forgotten Great Island. Before setting sail, however, the Carthaginians brought in their old friends and allies from northern Spain, the Kelts, as junior partners. It was a far-sighted move. The Kelts had considerable experience in agriculture, something that might prove handy on the Great Island and something that the Carthaginians themselves sorely lacked. For their part, the Kelts might not have needed much persuasion to join the Carthaginians on their journey to the Great Island. The Kelts despised the Romans as much as the Carthaginians did and might have shared their fears as to what would happen to them if they too fell under Roman control.

After crossing the Atlantic Ocean, the Kelts and the Carthaginians probably landed near what is now the city of Recife. Instead of being content to settle right where they landed, however, the Europeans began looking for an opening into the interior of South America. The newly arrived Europeans might have been motivated by fears that Roman pursuers were hot on their heels and ready to drag them back to a life of slavery in the Roman Empire. Such fears might not have been entirely unfounded. The ancient writers tell us that shortly after the destruction of Carthage, the Romans sent a naval expedition, led by one of the military commanders involved in the destruction of that city, down the coast of Africa to approximately the latitude of the Cape Verde Islands. After not finding what they were looking for, the Romans turned around and sailed back to the Mediterranean empty‑handed. Just what the Romans had been looking for was not recorded, but perhaps it was runaway Kelts and Carthaginians.

In their search for a suitable opening into the interior, the Kelts and the Carthaginians proceeded north along the Brazilian coast and eventually bumped into the mouth of the mighty Amazon River. They might have been initially tempted to settle there permanently. Agriculture was possible there, and at least the Kelts had experience in agriculture. But the Kelts’ experience had been in Europe, so they might not have had the skills to succeed in the lower Amazon, where different conditions might have required a different set of skills. Moreover, remaining in the lower Amazon would have meant facing hostile and numerically superior Indian tribes. So the Kelts and the Carthaginians started up the Amazon River and just kept going and going. Eventually after years of working their way up the river, they found the homeland they had been looking for in Peru. In addition to providing them with a somewhat familiar climate and an opportunity to practice a form of agriculture that they did understand, the new land offered them security. Distance protected them from the brutal Indian tribes to the east and the towering Andes Mountains protected them from any potential enemies to the west. So here the Kelts and the Carthaginians settled down after their heroic odyssey and started a new life that lasted until around 1500 AD.

Although the Carthaginians probably conceived the plan to migrate to the Great Island, in the end, it was the Kelts who put the greater stamp on the civilization that emerged in Peru. Professor Giffhorn has provided a medical explanation for this disparity. When the Carthaginians teamed up with the Kelts in their joint move to the Great Island, they did not realize that the Kelts, who had mainly been farmers, had a long history of contact with cattle and exposure to tuberculosis. Now by this time the Kelts themselves had developed immunity to tuberculosis, but the Carthaginians, who had not been farmers, had had no such contact and had developed no such immunity. So the intermingling of the Kelts and the Carthaginians might have hit the Carthaginians very hard, with many of them succumbing to tuberculosis that they contracted from the Kelts even as the Kelts themselves remained healthy.

The Chachapoyan civilization is long gone and the conventional view has it that the Chachapoyan people died out without leaving any descendants. In three remote Peruvian villages, however, there live people who look remarkably like Europeans. Having fair complexions, freckles, often red or blond hair (combined, oddly enough, with brown rather than blue eyes), the Gringuitos, as they are called by the Peruvians, resemble Irishmen more than they resemble South Americans. According to local lore, the Gringuitos had already been in Peru centuries before Columbus and are not descended from any of the Europeans who arrived after 1492. We can find a possible explanation for the origin of the Gringuitos in the writings of Spanish soldier and poet Garcilaso de la Vega (1501-1536). According to the latter, around the time that the Chachapoyan civilization was beginning to crumble, some of the Chachapoya saw the handwriting on the wall and fled into remote regions for their own safety. Such a flight might have protected them from both Incan warriors and from European diseases and enabled them to continue their lives and culture in another location, even down to the present day.

Modern DNA technology might throw some light on this subject. Archeologists would like to use DNA analysis on the above-mentioned Chachapoyan mummies, but the Peruvian Government up to now has not permitted such testing, perhaps out of fear that the results might offend Peruvian pride by showing that the Chachapoyan civilization was only European in origin. Professor Giffhorn and his team, however, were at least able to conduct DNA testing of saliva samples provided by a small number of the Gringuitos. The results of this random testing show a strong resemblance to the pattern of DNA found in northern and northwestern Spain, precisely the regions controlled long ago by Kelts. It would appear possible, therefore, that the Gringuitos are descended from the Chachapoya, who in turn were descended from the Kelts and the Carthaginians. If that is indeed the case, then the Gringuitos would have to be reckoned among history’s greatest survivors. Twice in their history, they escaped extinction in the nick of time. The first time, around 150 BC, they fled their Mediterranean homeland to escape from the Romans. Then after about 1500 BC, they fled their Chachapoyan homeland to escape from the Incas and the Europeans.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg