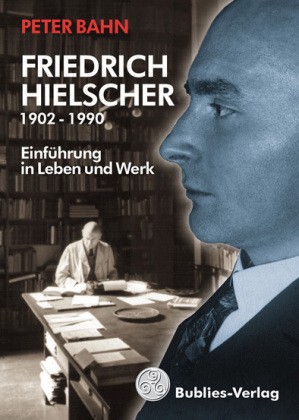

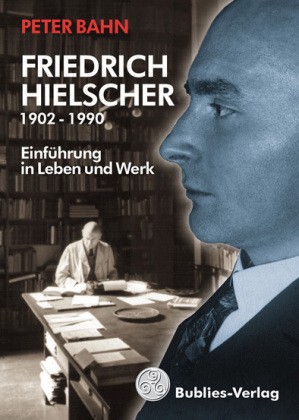

La légende de Friedrich Hielscher

Dr. Peter BAHN

La fondation d’une “Église” panenthéiste au XXe siècle et ses fausses interprétations ultérieures

Pendant des décennies, la vie et l’œuvre de l’auteur, philosophe religieux et érudit, le Dr. Friedrich Hielscher (1902-1990) a donné lieu à toutes sortes de fausses interprétations spéculatives. Cela est particulièrement vrai avec le genre de littérature “ésotérique” populaire, dans laquelle Hielscher a sans cesse été le sujet des plus folles spéculations et assertions. Au début des années 60, une “légende Hielscher” extrêmement négative était déjà née, à laquelle des embellissements encore plus hardis ont été régulièrement ajoutés jusqu’à aujourd’hui. Cette légende est, cependant, pratiquement à des années-lumière des véritables actions et intentions de Hielscher, et est dépourvue de toute référence à la réalité.

Pour pouvoir aller au fond de ces spéculations, et pour déterminer leurs sources d’origine, il est d’abord nécessaire d’examiner le cours de la vie de Hielscher. Concernant les années jusqu’en 1954, cela peut être assuré avant tout au moyen de son autobiographie (1). Concernant la période de temps ultérieure, il existe — dans la littérature, du moins — seulement des morceaux fragmentaires et dispersés d’information dont l’accès est difficile (2). Par contre, les archives existantes relatives à Hielscher sont beaucoup plus riches, en particulier sa production littéraire (3) et sa correspondance avec Ernst Jünger, qui dura de 1926 à 1986 (4).

Fils d’un marchand de textiles, Friedrich Hielscher était né le 31 mai 1902 à Plauen, dans le Vogtland, et grandit à Guben, en Niedersaulitz. À l’âge de 17 ans, il sortit diplômé du Lycée Humaniste de Plauen. Immédiatement après ses examens finaux, il rejoignit une unité des Corps Francs qui prit part aux combats de résistance contre les groupes polonais en Haute Silésie (5). Son unité fut plus tard incorporée dans l’armée allemande. En mars 1920, Hielscher refusa de participer au putsch de Kapp, et quitta l’armée (6). Il commença ensuite à étudier le droit à l’Université de Berlin et suivit aussi des cours à la Faculté des Sciences Politiques (7). Ces études de sciences politiques l’amenèrent en étroit contact avec Theodor Heuss, avec qui il se lia d’amitié pour la vie (8). À Berlin, Hielscher rejoignit le corps de duellistes étudiant “Normannia”, et jusqu’aux années 70 il fut une autorité active pour l’histoire du groupe, ainsi qu’un conférencier recherché concernant l’Assemblée de Kosen (9).

Alors que la courte période dans les Corps Francs fut marquée beaucoup plus par des aspirations à l’indépendance et à l’aventure que par des visions politiques concrètes (10), pendant le cours de ses études à Berlin Hielscher devint graduellement plus politisé. Après une affiliation temporaire au Reichsclub du Parti du peuple allemand national-libéral (11), il gravita vers les cercles des “gauchistes de la droite” et des “nouveaux nationalistes”. Ces petits cercles, qui tournaient autour de certains journaux et de projets de publications, cherchaient à combler le fossé entre l’arrière-plan intellectuel du mouvement des travailleurs socialistes et celui du nationalisme traditionnel (12). En même temps, il croisa le chemin de personnalités comme le philosophe culturel Oswald Spengler (13) et la sœur de Nietzsche, Elizabeth Förster-Nietzsche, cette dernière rencontre étant due aux nombreuses visites de Hielscher aux archives de Nietzsche à Weimar du fait de son travail promotionnel (14). En 1926, Hielscher termina son cursus par une thèse intitulée Die Selbstherrlichkeit : Versuch einer Darstellung des deutschen Rechtsgrundbegriffes (La souveraineté : un essai de présentation de la base de la loi allemande), pour laquelle il se vit décerner un double doctorat, summa cum laude, en philosophie du droit et en histoire du droit (15). Mais il trouva que son travail ultérieur, bureaucratique et réglementé, en tant que clerc juridique, était un tel supplice qu’en novembre 1927 il fut déchargé de la fonction publique à sa propre requête (16). Pendant le reste de sa vie, il vécut comme un universitaire — tant bien que mal — avec les bénéfices de publications, de cours et de commissions de recherche occasionnelles.

Hielscher, qui avait entre-temps développé un étroit contact personnel avec Ernst Jünger, fut à partir de 1926 un collaborateur actif aux divers journaux liés au « nouveau nationalisme » national-révolutionnaire. Son premier essai parut à la fin de 1926 dans le magazine Neue Standarte-Arminius : Kampfschrift für deutsche Nationalisten. Avec son titre, Innerlichkeit und Staatskunst (Intériorité et art étatique), il indiqua dès le début qu’il ne se préoccupait pas d’activité politique superficielle, car les choses n’en étaient pas « au commencement d’un nouveau départ, mais plutôt à la fin du vieil effondrement » (17). Cet effondrement ne pouvait être surmonté que par une nouvelle « foi (...) qui portera l’avenir allemand et sans laquelle le nouveau travail ne sera pas commencé » (18).

Avec l’accent mis par ce premier texte sur l’importance fondamentale d’une nouvelle foi, un trait avait déjà émergé dans l’œuvre de Hielscher qui allait rapidement s’intensifier, et qui resterait prédominant jusqu’à la fin de sa vie. Hielscher ne pensait “politiquement” que d’une manière secondaire et transitoire ; il se préoccupait beaucoup plus de tirer un nouvel “art étatique” des concepts religieux. Cela était déjà clair à la fin des années 20 au vu de sa correspondance avec Ernst Jünger. En conséquence, en novembre 1929 il envoya à Jünger une “déclaration de foi” (Bekenntnis) idéologico-religieuse, et dans une autre lettre quelques semaines plus tard il parla de la nécessité de la naissance d’une « Église invisible » qui serait efficace en termes de foi tout comme de politique (19). Vivant à l’époque dans la solitude d’un presbytère de la région de Lausitz, où un ancien ami d’école servait comme pasteur protestant, Hielscher travaillait sur son livre Das Reich, qui fut publié en 1931 (20). Celui-ci fut précédé par les premiers numéros d’un périodique du même titre que Hielscher avait édité depuis septembre 1930. Un cercle d’adeptes, loyal à Hielscher en tant que spiritus rector, se forma progressivement autour du journal et à partir des lecteurs du livre, qui avait provoqué un débat considérable. Jusqu’en 1933 ce cercle fut essentiellement tiré des rangs du Mouvement de la Jeunesse et des groupes de jeunesse nationaux-révolutionnaires (21).

L’unité de foi et de politique postulée par Hielscher, d’« intériorité et art étatique », ne fut pas sans conséquence sur la structure et l’activité de son cercle. Dans les années entre 1932 et 1935, l’association grandit, selon les mots de Hielscher, à la foi « comme une résistance contre la populace, et comme une Église » (22). Hielscher considéra toujours le mouvement national-socialiste comme une « populace », contre qui il se trouvait en opposition diamétrale pour des raisons idéologico-religieuses. En fait, le cercle autour de Hielscher se voyait à la fois comme une « Église embryonnaire » avec les activités rituelles correspondantes, et comme un « État embryonnaire » avec la tâche de résister au national-socialisme (23), bien qu’il soit peu probable que tous les membres politiquement actifs du cercle aient participé avec la même intensité aux aspects religieux du groupe. En tout, le groupe était formé d’environ cinquante personnes, dont les noms peuvent être déterminés à partir des archives relatives à Hielscher (24).

Les activités du cercle, à la fois comme « Église » et comme groupe de résistance, étaient menées sur la base d’un système idéologico-religieux extraordinairement complexe. Ceci n’avait pas été emprunté par Hielscher à d’autres sources sous une forme finie, mais fut développé successivement à partir d’axiomes fondamentaux spécifiques. D’importance centrale était l’idée de la foi comme « base de l’action » incontestable, et donc de leitmotiv essentiel pour toute action humaine (25). À un niveau subordonné à cette signification de la foi en général (c’est-à-dire, d’une foi en tant que telle), Hielscher plaçait sa propre théologie concrète avec sa vision particulière sur Dieu, les dieux, et l’homme — une vision qu’il définissait comme « païenne ».

Le point de départ était la perception panenthéiste de Dieu comme « l’Éternel, en qui tout est contenu » (26). Ainsi, Dieu n’était pas extérieur au monde, mais au contraire le monde était en Lui ; il n’était pas le Créateur, mais plutôt celui qui (à partir de lui-même) crée continuellement. Hielscher reliait cela à diverses notions. De la compréhension du monde par Nietzsche comme “volonté de puissance”, il extrapolait l’idée de devenir un « avec le monde éternellement en devenir » (27). De cela pouvait « être perçue … une conscience de Dieu » (28). En même temps, il revenait spécifiquement à la pensée de l’hérétique et érudit du début du IXe siècle, Jean Scot Erigène, d’après qui, « Dieu est tout ce qui est éternel et tout ce qui est advenu » (29). Erigène décrivait aussi Dieu comme une « unité multiple à l’intérieur de lui-même » (30). Cette idée domina exclusivement et complètement les convictions religieuses de Hielscher et de son cercle jusqu’à la fin des années 30, avant d’être élargie (avec des conceptions qui étaient systématiquement dérivées du penseur susmentionné) pour inclure des « dieux » ou des « messagers célestes », qui en tant que « particularités » (Besonderungen) personnelles du « tout-puissant et seul vrai Dieu » apparaissaient comme médiateurs entre ce dernier et les êtres humains. À cet égard, des éléments polythéistes trouvés dans la pensée classiciste allemande (en particulier dans les œuvres de Gœthe et de Hölderlin) — mais habillés par Hielscher en dieux de la mythologie germanique (« Wode », « Thor », « Loki », « Freya », « Sigyn », etc.) — furent repris et incorporés structurellement (31). En tant qu’« âme », l’être humain aussi n’était rien d’autre que l’une des « particularités » émanant de la plénitude du seul vrai Dieu. Pour Hielscher, cela conduisait en conséquence à un rejet des conceptions occidentales modernes de l’individu autonome : chaque « âme » (c’est-à-dire chaque être humain) reçoit « sa propre essence à tout moment de Dieu » (32).

De ces conceptions de base, à partir du début des années 30 le cercle Hielscher développa un système de croyance qui se différenciait continuellement par de nouvelles manifestations, ainsi que par une pratique liturgique avec des cérémonies pour le cycle de l’année et le cours de la vie. Avec l’inauguration du nouvel appartement de Hielscher à Falkenhain près de Berlin le 27 août 1933 vint la première « observance » (Andacht) officielle de l’« Église ». Celle-ci fut dès lors considérée comme la véritable date de fondation de l’Église, que Hielscher nomma la Unabhängige Freikirche (UFK), l’Église Libre Indépendante (33). Cela fut suivi par des élaborations liturgiques, orientées exclusivement d’après les études folkloriques, mythologiques et historico-religieuses faites par les membres du groupe ; ces études étaient presque exclusivement à diffusion interne. En 1941, ils réussirent à terminer une série annuelle de rituels païens constituée de 24 cérémonies (34). Chaque cérémonie était consacrée à l’un des 12 dieux germaniques, et était combinée (comme Ernst Jünger le laissa entendre dans une entrée de son Journal de Paris en octobre 1943, écrite après une rencontre avec Hielscher) avec diverses correspondances symboliques — signes, arbres, fleurs, animaux, aliments, boissons, « couleurs inhérentes » et « couleurs apparentes » (Wesensfarben und Erscheinungsfarben) (35). En même temps, en tant que chef de l’UFK, Hielscher accomplit aussi des cérémonies de baptême et de mariage pour des membres de son cercle, suivies plus tard par les premières funérailles du groupe (36).

Structurellement, la liturgie des services religieux spécifiques de l’UFK — avec leurs invocations, prières, chants, et lectures — contenait aussi des éléments qui pouvaient clairement être trouvés, de cette manière ou d’une manière similaire, parmi les communautés de la foi chrétienne. Les différences sont essentiellement en termes de contenu, qui dans l’UFK se distinguait par le panthéon des dieux germaniques avec le « seul vrai Dieu » au-dessus de lui. Mais il y avait quelque chose d’autre. Dans son autobiographie, Hielscher se décrivit expressément — traçant une distinction explicite avec Ernst Jünger — comme un « mystique » (37). La signification imprégnant les cérémonies à l’intérieur de l’UFK se trouvait donc dans un contexte très spécifique. Hielscher soulignait en conséquence qu’avec ces cérémonies, « l’Église célébrerait la domination du céleste dans cet espace et dans ce temps » (38) et parlait de « revenir de la cérémonie pour [faire] nos devoirs quotidiens avec une énergie et un pouvoir nouveaux » (39). Cela faisait penser à une compréhension mystique de la religion, voyant l’expérience contemplative intérieure du numineux comme une source d’énergie, particulièrement pour le croyant individuel prenant part aux cérémonies.

Pour Hielscher et son cercle, la résistance contre le national-socialisme se nourrissait à des sources religieuses. C’était beaucoup moins une critique des mesures politiques individuelles prises par le régime NS — bien qu’ici aussi, Hielscher développa diverses positions dissidentes, dont la discussion sort du cadre de cet essai — qu’un rejet de principe. À cause de son manque de connexion transcendantale, le règne NS était vu par le cercle Hielscher comme un niveau décadent d’État, une forme de règne de la populace qui — en particulier à cause de son idéologie raciale biologique — était devenue asservie à la « matière » et à ce qui est purement matériel. Pour Hielscher, l’infiltration et la subversion depuis l’intérieur semblait être un chemin praticable de résistance, bien qu’à la lumière de la faiblesse numérique de son cercle cette stratégie se heurta rapidement à des facteurs limitants. Si des membres du cercle Hielscher parvinrent à occuper des positions de niveau intermédiaire dans l’armée, dans le contre-espionnage, et dans les SA et les SS, très peu de choses — en plus de rassembler des informations et d’offrir occasionnellement une aide à des victimes individuelles de la persécution politique — purent être faites.

Une exception fut l’influence exercée sur l’Ahnenerbe, l’organisation de recherche SS fondée le 31 juillet 1935, et dont Wolfram Sievers, un jeune ami de Hielscher et aussi un membre de l’UFK, parvint à devenir l’administrateur (40). Au-delà de son but originel de faire progresser l’étude de la « préhistoire spirituelle » (Geistesurgeschichte) (41), l’Ahnenerbe, un objet de prestige pour Heinrich Himmler, se subdivisa graduellement en de nouveaux départements de recherche consacrés à l’histoire de l’art, aux sciences naturelles, à la médecine, et même à la technologie (42). En résultat de l’implication ultérieure des départements médicaux dans les expériences humaines barbares conduites par les SS, Sievers, qui en dépit de sa désapprobation religieusement motivée de ces incidents s’était trouvé incapable d’agir ouvertement contre eux, fut condamné à mort au procès de Nuremberg et pendu (43). Hielscher — qui avait même reçu, sous la protection de son ami (44), des commissions de recherche temporaires de l’Ahnenerbe concernant des matières folkloriques et historico-culturelles — tenta sans succès jusqu’à la fin d’obtenir une grâce pour Sievers. Immédiatement avant l’exécution, il rendit visite à Sievers en prison et célébra une cérémonie d’adieu religieuse avec lui, en accord avec les observances de son Église païenne (45). C’est cet événement en particulier qui donna lieu plus tard à un grand nombre de spéculations extravagantes.

Quand c’était faisable, Hielscher tira avantage de ses activités pour l’Ahnenerbe, qui étaient occasionnellement combinées avec des voyages de recherche, pour aider des gens qui étaient politiquement ou racialement persécutés (46), et pour cultiver des contacts avec divers groupes de la résistance antinazie (47). En septembre 1944, il fut arrêté par la Gestapo en liaison avec l’assassinat manqué de Hitler par le comte von Stauffenberg, emprisonné pendant quelques mois, et torturé. Ce fut l’intervention de Sievers à cette époque qui conduisit à sa libération sous « condition de servir au front », et qui lui sauva finalement la vie (48).

Après 1945, le cercle Hielscher cessa toute activité politique et se concentra exclusivement sur des recherches religieuses cadrant avec les paramètres de l’UFK. Basant sa perspective sur une vision cyclique de l’histoire et employant une terminologie saisonnière, Hielscher pensait que l’humanité se trouvait dans un « hiver » historique (qui avait commencé vers 1800 avec la Révolution française et la montée de l’industrialisation) au milieu duquel on devait procéder d’une « impossibilité de l’État » fondamentale, nécessitant une construction conceptuellement nouvelle de l’État. En contraste, « l’Église dans l’hiver » était vue comme la « racine du printemps, et la première étape du Reich » (49), et le nouveau centre de ses recherches apparaissait comme la prochaine étape logique. Pendant des décennies, cela resta le travail de l’UFK. Et tout comme elle l’avait fait durant le Troisième Reich, sous la République Fédérale d’Allemagne l’UFK maintint une isolation presque complète vis-à-vis de l’extérieur. Des années 50 jusqu’aux années 80, l’activité de l’UFK fut caractérisée par des « journées de l’Église » annuelles, des célébrations internes, et l’accumulation d’une masse de compositions internes qui existent sous forme hectographique ; celles-ci traitent surtout de questions de théologie et de philosophie de l’histoire (50). L’âge avancé de ses membres (car des membres nouveaux et plus jeunes pouvaient difficilement être introduits) et 2 crises de l’« Église », en 1969-70 et 1983-84 (51), affaiblirent finalement un cercle qui n’avait jamais été particulièrement fort — à tel point que dans les années précédant la mort de Hielscher en mars 1990, l’UFK était principalement composée de lui-même et de son épouse Gertrud.

En conclusion, on peut souligner que Hielscher, qui sortit du courant national-révolutionnaire politiquement motivé de la période de Weimar, s’était déjà tourné à la fin des années 20 vers des thèmes religieux d’une manière intensifiée, et qu’en résultat de cette tendance il avait créé sa propre Église « païenne ». À première vue, l’UFK semble comparable à de nombreuses autres initiatives religieuses völkisch contemporaines, mais elle différait de celles-ci par sa formulation d’un système théologique strictement axiomatique et par un rejet consécutif de toutes les conceptions raciales-biologiques, et donc matérialistes. Hielscher et son cercle désapprouvèrent le système NS depuis le début, mais tentèrent de faire usage de leurs positions par l’infiltration d’institutions spécifiques (l’Ahnenerbe en particulier), dans le cadre d’un effort de résistance. En faisant cela, Hielscher entra en conflit mortel avec la Gestapo. Après 1945, il se retira presque complètement de la vue du public, et à part ses activités avec la société de duellistes étudiants et la publication de son autobiographie, il s’employa seulement à cultiver les pratiques mystiques-contemplatives de son Église.

À la place de cette histoire exacte, qui peut être vérifiée complètement par les preuves et les archives littéraires, à partir de 1960 une toile de fausses interprétations, de spéculations et de formulations légendaires commença à se développer, qui n’avait plus aucun rapport avec la vie et l’œuvre réelles de Hielscher. Cependant, il est nécessaire d’aborder la question, car une grande partie de ce que le grand public, à l’intérieur et à l’extérieur de l’Allemagne, connut sur Hielscher dans les dernières décennies a été influencée et embrouillée par ces formulations légendaires. Une analyse impartiale de Hielscher — et particulièrement de son système théologique, qui contient quelques éléments très remarquables — peut difficilement avoir lieu tant qu’un roncier de mythes négatifs obstrue l’accès nécessaire.

À l’origine de la formulation légendaire se trouvait le livre Le matin des magiciens, par Louis Pauwels et Jacques Bergier, publié en France en 1960 et bientôt traduit dans diverses langues. L’intention de base des auteurs était de souligner certains aspects de la réalité terrestre qui restent en-dehors de l’actuel modèle d’explication rationaliste et positiviste. Sur cette toile de fond, ils soulignaient — et pas d’une manière détaillée, finalement — divers cotés "obscurs" et "bizarres" de l’histoire intellectuelle du XXe siècle et suggéraient des références historiques (réelles ou spéculatives). L’arrière-plan supposément ésotérique ou « occulte » du national-socialisme était d’un intérêt particulier. Il était inévitable que dans ce contexte, les prédilections de Heinrich Himmler pour la mythologie germanique et pour les rituels des Männerbünde traditionnels, l’histoire des Châteaux de l’Ordre du NS, et les activités de recherche appropriées de l’Ahnenerbe aient aussi été mentionnées (52).

À cause de la cérémonie d’adieu maintenant bien connue avant l’exécution de Wolfram Sievers — absolument pas mentionnée par Hielscher dans son autobiographie —, Hielscher se trouva lui-même dans les vues de Pauwels et Bergier. Ils le présentèrent d’emblée comme le « maître spirituel » de Sievers (53), ce qui avait bien sûr une certaine plausibilité du fait de l’appartenance de Sievers au cercle de résistance à motivation religieuse de Hielscher. Mais devant l’histoire organisationnelle suffisamment documentée de l’Ahnenerbe (54), beaucoup plus aventurée était l’assertion factuelle dans le même paragraphe que la création de son organisation aurait pu en fait procéder d’une « initiative privée » de Hielscher (55), qui avait de plus noué une « amitié mystique » avec l’explorateur suédois Sven Hedin. Ce que nous devons faire de cette « amitié mystique » — qui n’est mentionnée ni dans l’autobiographie de Hielscher (où il parle souvent volontiers et abondamment de ses rencontres et amitiés avec diverses personnalités) ni dans sa production littéraire — est une question que Pauwels et Bergier laissent sans réponse. Néanmoins le détour imaginatif vers les premières explorations de Hedin en Asie Centrale cadrait opportunément avec l’élaboration d’une « doctrine secrète » nationale-socialiste, apparemment influencée par l’Extrême-Orient, dont la genèse et l’établissement étaient supposés avoir été substantiellement influencés par Sven Hedin – et par Hielscher (56).

En fait, Pauwels et Bergier concédaient quelques phrases plus tard que Hielscher ne fut jamais un national-socialiste, mais affirmaient qu’un lien existait à travers sa communauté « avec les doctrines ‘magiques’ des grands maîtres du national-socialisme » (57). Mais c’est précisément par cette attribution d’idées « magiques » à Hielscher que Pauwels et Bergier révélaient en fait combien ils en connaissaient peu sur son système religieux-cosmologique, car Hielscher s’était toujours fermement opposé au concept et à la pratique de la « magie ». Il insistait particulièrement là-dessus dans son autobiographie, qui fut disponible dès 1954 (et qui était donc parfaitement accessible à Pauwels et Bergier). Dans celle-ci, dénotant une différence caractéristique entre sa vision du monde et celle de Ernst Jünger, il qualifiait sa perspective personnelle de mystique, alors que celle de Jünger était magique (58). Et il y avait encore une autre source pour ce rejet de la magie qui était rigoureusement déduit du système religieux-cosmologique de Hielscher, d’après lequel il n’est pas possible pour l’être humain « d’approcher les dieux, de s’attribuer leur bénédiction, de s’élever jusqu’à eux » (59). Le 11 décembre 1956, Hielscher écrivit à Friedrich Georg Jünger, le frère d’Ernst Jünger, que la magie était la « tentative inadaptée, mais toujours coupable, d’utiliser des moyens terrestres, à savoir ceux de la sorcellerie, pour mettre le Céleste à son service ». La magie blanche était encore plus répréhensible que la magie noire, car le magicien « blanc » était coupable de « désirer soumettre un bon esprit », au lieu d’un mauvais esprit, « à sa propre volonté » (60).

Mais Pauwels et Bergier ne s’intéressaient pas à tout cela. Bien éloignés de toute source concernant la vie et l’œuvre de Hielscher, ils lui attribuaient finalement « un rôle important dans l’élaboration de la doctrine secrète [nationale-socialiste] » (61), cette froide et cruelle doctrine supposément transmise par Sven Hedin à partir de l’Asie, qui se trouve derrière les événements politiques et qui selon les auteurs pourrait aussi expliquer les actions des protagonistes du national-socialisme et en particulier des SS. Une conjecture grandiose de ce genre, tirée du néant et diffusée internationalement à travers le livre de Pauwels et Bergier en grandes éditions, établit un sol fertile idéal dans les années suivantes pour des spéculations encore plus hardies et des affirmations de plus en plus téméraires concernant le rôle de Hielscher pendant l’ère NS.

Un exemple typique à cet égard est le livre The Spear of Destiny (La lance du destin) de l’auteur britannique Trevor Ravenscroft, dans lequel Hielscher — bien sûr à nouveau sans l’ombre d’une preuve et en résultat de la « méthode » des racontars sans mesure — est une fois de plus décrit comme ayant été le chef spirituel de l’Ahnenerbe, et « la plus importante figure en Allemagne après Adolf Hitler lui-même » (62). « Le Führer », d’après Ravenscroft, demanda à Hielscher de le conseiller « dans toutes les matières occultes », et dans l’éventualité d’une victoire allemande dans la seconde guerre mondiale, Hielscher « aurait bien pu devenir le Grand Prêtre d’une nouvelle religion mondiale qui aurait remplacé la Croix par le Svastika » (63). Finalement, Ravenscrof imaginait aussi que Hielscher lui-même était celui qui avait développé un mystérieux « rituel de l’air suffoquant » par lequel des membres sélectionnés des SS « prêtaient serment d’allégeance irrévocable aux puissances sataniques » (64). Le fait que même dans la seconde édition révisée de son livre (65), Ravenscroft écrivait encore « Heilscher » au lieu de « Hielscher » est probablement indicatif de la connaissance des faits et des sources par cet auteur et quelques autres de ce genre.

Un autre auteur de langue anglaise, Gerald Suster, approcha le sujet d’une manière similaire. Dans un livre portant le titre sensationnel : Hitler : Black Magician, il se sentit obligé d’écrire que Hielscher avait déjà fondé l’Ahnenerbe en 1933, après quoi elle reçut une reconnaissance « officielle » en 1935 (66). D’après Suster, Hielscher influença les SS en particulier, et à un degré beaucoup plus élevé que ce qu’on en savait généralement » (67). Suster aussi n’avait pas l’ombre d’une preuve pour ces affirmations, sans même parler de sources pouvant être vérifiées par une bibliographie ou par des archives. La bibliographie de son livre de 222 pages tient en moins de 2 pages. Bien que la bibliographie ne contenait ni l’autobiographie de Hielscher ni la littérature spécialisée sur l’Ahnenerbe, l’édition britannique du Matin des magiciens de Pauwels et Bergier, publiée en 1964, se trouve être une fois encore l’une des sources principales (68).

Les mêmes associations spéculatives, faisant pour la plupart des références directes et explicites à Pauwels/Bergier et Ravenscroft, peuvent aussi être trouvées dans le volumineux livre Das Schwarze Reich, signé de l’auteur « E.R. Carmin », manifestement un pseudonyme, ce dernier affirmant révéler l’influence considérable de toutes sortes de sociétés secrètes sur la politique du XXe siècle. Le livre parut en 1994 chez un petit éditeur de Rhénanie, passa d’abord relativement inaperçu, mais connut une large diffusion 3 ans plus tard lorsqu’il fut publié en édition de poche par la célèbre Heyne Verlag de Munich. « Carmin » non seulement reprit les habituelles formulations légendaires de ses antécédents littéraires, comme l’« amitié mystique » entre Hielscher et Sven Hedin, mais prit soin de concocter — comme ingrédient original et additionnel à la florissante légende Hielscher — des liens entre l’Église clandestine de Hielscher (dont, cependant, il ne connaissait pas le nom) et le désir d’Alfred Rosenberg de créer une Église nationale du Reich (69). En passant, « Carmin » décrit aussi le principal ouvrage historico-philosophique de Hielscher, Das Reich, comme un « roman » (70), jetant une lumière révélatrice à tous égards sur ce genre de recherche « historique » contemporaine.

Une contribution complètement unique à la « légende Hielscher » qui non seulement s’inspira de spéculations antérieures mais aussi contribua fortement à celles-ci fut faite par l’auteur chilien et ardent admirateur de Hitler, Miguel Serrano, avec son livre El cordon dorado : Hitlerismo esoterico. Ce dernier parut en espagnol en 1978 et fut publié dans une traduction allemande en 1987. Dans ce livre, Serrano expose en détail une ligne complète de tradition spirituelle, incluant les doctrines de l’hindouisme, de l’alchimie médiévale, des Templiers, des Cathares et des Rosicruciens, qui conduit directement à un national-socialisme interprété d’une manière « ésotérique » dans lequel un Adolf Hitler survivant continue à vivre au Pôle Sud. Au milieu de tout cela, Hielscher, parmi tous les gens respectueusement appelés « les initiés » par Serrano, était placé à la même hauteur que les « chefs supérieurs et inconnus de l’Hitlérisme » et même élevé au niveau d’un « chef spirituel des SS » (71).

L’appendice bibliographique de Serrano manquait lui aussi de toute trace de l’autobiographie de Hielscher, des autres textes publiés par Hielscher, et du matériel approprié qui se trouve dans les archives. Mais le Matin des magiciens se trouve encore une fois parmi les sources données, cette fois-ci dans sa traduction espagnole de 1963 (72). Cela souligne à nouveau le rôle joué par Pauwels et Bergier pendant des décennies comme fournisseurs de slogans pour un genre complet de littérature. Les diverses tentatives de diaboliser la vie et l’œuvre de Hielscher en termes d’un bizarre ésotérisme « noir » (comme dans les ouvrages de Pauwels et Bergier, Ravenscroft, Suster et « Carmin ») recoupent ici la tentative de Serrano de l’utiliser dans le contexte d’un hitlérisme « ésotérique » et « tantrique ».

Complètement négligé était par contre tout examen des positions réelles de Hielscher, et particulièrement des éléments fondamentaux de son système religieux-cosmologique. Au mieux, des fragments et des lambeaux conceptuels furent extraits, volontairement mal interprétés et insérés dans des contextes historiques contemporains auxquels ils étaient en fait diamétralement opposés. Cela est particulièrement vrai dans le cas du peu qui était connu (comme ce qui venait du journal de Ernst Jünger) concernant l’Église libre païenne de Hielscher, et qui fut plus tard interprété avec empressement comme une indication de « rites » satanistes et de « doctrines secrètes ». Le refus strict et permanent de Hielscher de permettre un plus large accès aux dogmes et à la liturgie de son Église était — de son point de vue — logique et bien-fondé. Il était basé sur la supposition que c’était précisément à la lumière des expériences négatives avec le Troisième Reich que le petit cercle de ses fidèles devait être protégé, et qu’en général seules quelques personnes étaient assez mûres en esprit et en caractère pour saisir le système de croyance axiomatiquement construit de l’UFK, intuitivement aussi bien que mentalement.

Involontairement, cependant, cette position clandestine encouragea la croissance illimitée de légendes et se révéla finalement comme contre-productive. C’est seulement après un examen minutieux, basé sur les sources existantes, sur les motivations, les fondements spirituels et les pratiques réelles du cercle de Hielscher — qui existait encore dans les années 80 — que ces formulations légendaires seront écartées et permettront l’étude d’un aspect fertile et très intéressant de l’histoire intellectuelle du XXe siècle.

♦ Peter Bahn (traduit d’allemand en anglais par Michael Moynihan et Gerhard)

• Cet essai est originellement paru sous le titre « Die Hielscher-Legende : Eine panentheistische ‘Kirchen’-Gründung des 20. Jahrhunderts und ihre Fehldeutungen » dans le journal allemand Gnostika, N° 19 (octobre 2001), pp. 63-76. Cette nouvelle version, traduite en anglais et avec des références bibliographiques élargies, est publiée par TYR avec l’aimable autorisation de l’auteur.

NOTES

[1] Cf. Friedrich Hielscher, Fünfzig Jahre unter Deutschen [Cinquante ans parmi les Allemands], Hambourg, Rowolt 1954.

[2] Ici les articles suivants doivent être mentionnés en particulier : Marcus Beckmann, « Dem anderen Gesetz gehorschen : Zum Tode Friedrich Hielschers », in Fragmente 6 (1990), pp. 4-13 ; Werner Barthold, « Die geistige Leistung Friedrich Hielschers für das Kösener Corpsstudentum », in Einst und Jetzt : Jahrbuch des Vereins für corpsstudentische Geschichtsforschung, vol. 36 (1991), pp. 279-82 ; Karlheinz Weissmann, « Friedrich Hielscher : Eine Art Nachruf », in Criticon 123 (janvier/février 1991), pp. 25-28 ; Peter Bahn, « Glaube–Reich–Widerstand : Zum 10. Todestag Friedrich Hielschers », in Wir selbst : Zeitschrift für nationale Identität, Nos 1-2 (2000), pp. 21-33; Peter Bahn, « Ernst Jünger und Friedrich Hielscher : Eine Freudschaft auf Distanz », in Les Carnets Ernst Jünger, N° 6 (2001), pp. 127-45.

[3] C’est le Dépôt Friedrich Hielscher dans les Archives du District de Schwarzwald-Baar (Willingen-Schwenningen) ; un index électronique des archives est actuellement en préparation. Abrégé SBDA à partir de maintenant.

[4] Celle-ci se trouve parmi les documents Ernst Jünger aux Archives de Littérature Allemande à Marbach ; il y a aussi d’autres lettres de Hielscher dans d’autres collections de papiers non-publiés, comme ceux concernant Friedrich Georg Jünger.

[5] Cf. Hielscher, Fünfzig Jahre, pp. 21-29.

[6] Cf. Hielscher, Fünfzig Jahre, p. 31.

[7] Cf. Hielscher, Fünfzig Jahre, pp. 33-35.

[8] Cf. Hielscher, Fünfzig Jahre, pp. 45-47.

[9] Friedrich Hielscher, Fünfzig Jahre, pp. 35-38, et Barthold, 1991. Concernant les activités de Hielscher dans la société de duellistes, voir aussi Hermann Rink, « Friedrich Hielscher » in Thomas Raveaux et Marcus Beckmann, eds., Veritati : Festschrift für Friedrich Hielscher zum 85. Geburtstag (Würzburg: auto-édition, 1987), pp. 19-22.

[10] Cf. Hielscher, Fünfzig Jahre, pp. 21-22.

[11] Cf. Hielscher, Fünfzig Jahre, pp. 41-44.

[12] Concernant ce courant en général, et le rôle – partiel et marginal – de Hielscher, Cf. entre autres : Karl O. Paetel, Versuchung oder Chance ? Zur Geschichte des deutschen Nationalbolchewismus (Göttingen, Musterschmidt, 1965 ; new ed., Koblenz, Bublies, 2000) ; Otto-Ernst Schüddekopf, Nationalbolchewismus in Deutschland 1918-1933 (Frankfurt/Berlin/ Vienna : Ullstein, 1972) ; Louis Dupeux, Nationalbolchewismus in Deutschland 1918-1933 : Kommunistische Strategie und konservative Dynamik (Munich, Büchergilde Gutenberg, 1985) ; Suzanne Meinl, Nationalsozialisten gegen Hitler : Die nationalrevolutionäre Opposition um Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz (Berlin, Siedler, 2000). Le texte standard biographique/bibliographique sur ce sujet est Armin Mohler, Die Konservative Revolution 1918-1932 : Ein Handbuch, 3ème éd., élargie avec un volume supplémentaire contenant aussi des corrections (Darmstadt : Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1989). Hielscher, que Möhler décrit correctement comme « bâtisseur de système » typique parmi les nationaux-révolutionnaires, est détaillé à la p. 450.

[13] Cf. Hielscher, Fünfzig Jahre, pp. 82-83.

[14] Cf. Hielscher, Fünfzig Jahre, p. 84.

[15] Cf. Hielscher, Fünfzig Jahre, p. 105. Sa thèse, qui contenait beaucoup de références à la pensée de Nietzsche et de Spengler, parut sous forme de livre en 1930, publiée par Frundsberg-Verlag, Berlin.

[16] Cf. Hielscher, Fünfzig Jahre, p. 111.

[17] Cf. Friedrich Hielscher, « Innerlichkeit und Staatskunst », in Neue Standarte-Arminius: Kampfschrift für deutsche Nationalisten, numéro du 26 décembre 1926, pp. 6-8. Cité ici et plus bas d’après la réimpression aux pp. 335-38 de Jahrbuch zur Konservative Revolution 1994 (Cologne : Anneliese Thomas, 1994), p. 335.

[18] Cf. Hielscher, 1926 (1994), p. 337.

[19] Cf. les lettres de Hielscher datées du 28 novembre 1929 et du 12 janvier 1930, dans les documents Ernst Jünger aux Archives de Littérature Allemande.

[20] Cf. Friedrich Hielscher, Das Reich (Berlin, Das Reich, 1931).

[21] Sur la formation du cercle Hielscher et ses efforts pendant la dictature NS, Cf. Rolf Kluth, « Die Widerstandgruppe Hielscher » in Pusl : Dokumentationschrift zur Jugendbewegung, N° 7 (déc. 1980), pp. 22-27.

[22] Cf. Hielscher, Fünfzig Jahre, p. 237.

[23] Cf. Friedrich Hielscher, « Die Entwicklung unserer Kirche » [Le développement de notre Église], texte aux SBDA, documents Hielscher, N° 73, p. 1-2.

[24] Cf. Friedrich Hielscher, « Bericht über die unterirdische Arbeit gegen den Nationalismus » [Rapport sur le travail souterrain contre le national-socialisme], texte aux SBDA, documents Hielscher, N° 140 (avec index des personnes appartenant au cercle).

[25] Cf. Friedrich Hielscher, Die Selbstherrlichkeit : Versuch einer Darstellung des deutschen Rechtsgrundbegriffes (Berlin, Frundsberg, 1930), pp. 63-64.

[26] Cf. lettre de Hielscher datée du 28 novembre 1929, dans les documents Ernst Jünger aux Archives de Littérature Allemande.

[27] Cf. Hielscher, Die Selbstherrlichkeit, 1930, p. 83.

[28] Cf. Hielscher, Die Selbstherrlichkeit, p. 81.

[29] Cf. Johannes Scotus Eriugena, Über die Einteilung der Natur, trad. Par Ludwig Noak (Hambourg, Felix Meiner 1994), p. 325.

[30] Cf. Eriugena, Über die Einteilung der Natur, p. 324.

[31] Cf. « Die 1. Klasse des heidnischen Glaubensunterrichts während der Schule » [La première classe de l’enseignement religieux païen à l’école], texte aux SBDA, documents Hielscher, N° 15 (probablement écrit par Hielscher).

[32] Cf. la lettre de Hielscher à Alfred Schäffer datée du 23 janvier 1931, dans la collection Walter Ehlers aux Archives de Littérature Allemande.

[33] Cf. SBDA, documents Hielscher, N° 81, et le document public du notaire de Triberg daté du 6 juillet 1966 concernant une déclaration sous serment de Hielscher sur la fondation de la « Unabhängige Freikirche » en 1933 (copie en possession de l’auteur).

[34] Cf. Friedrich Hielscher, « Die Entwicklung unserer Kirche », p. 2.

[35] Cf. Ernst Jünger, Strahlungen II : Das zweite Pariser Tagebuch, „Kirchhorster Blätter : Die Hütte im Weinberg“, édition de poche (Munich, Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag 1988), pp. 172-73 (entrée du 16 octobre 1943). Ernst Jünger lui-même ne fut jamais membre de l’Église de Hielscher, mais fut l’une des quelques personnes extérieures informées de son existence et de son développement par son vieil ami Hielscher. Les diverses lettres et pièces jointes de Hielscher à Jünger jusqu’aux années 1980 doivent être notées à cet égard (Cf. la correspondance Ernst Jünger-Friedrich Hielscher dans les documents Ernst Jünger aux Archives de Littérature Allemande).

[36] Cf. Hielscher, « Die Entwicklung », p. 2.

[37] Cf. Hielscher, Fünfzig Jahre, p. 117.

[38] Cf. Friedrich Hielscher, « Der Aufbau der Kirche » [La construction de l’Église], texte N° 16 dans les documents Hielscher aux SBDA, p. 18.

[39] Cf. Hielscher, « Der Aufbau », p. 18.

[40] Cf. Michael H. Kater, Das Ahnenerbe der SS 1935-1945 (Stuttgart : Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, 1974), p. 38.

[41] Cf. Kater, 1974, p. 27. Sur les connotations originelles du nom de l’institution, voir l’article de Joscelyn Godwin sur Hermann Wirth dans ce numéro de TYR.

[42] Cf. Kater, Das Ahnenerbe, p. 215.

[43] Pour une évaluation critique du rôle de Sievers, Cf. Kater, Das Ahnenerbe, pp. 317-19, et la description antérieure plus positive de Sievers dans Alfred Kantorowicz, Deutsches Tagebuch, Pt. 1 (Munich, Kindler, 1959), pp. 496-507.

[44] Cf. Kater, Das Ahnenerbe, p. 323.

[45] Cf. Hielscher, Fünfzig Jahre, p. 453-54.

[46] Cf. Hielscher, Fünfzig Jahre, p. 444-47.

[47] Cf. Friedrich Hielscher, « Die Hielscher-Gruppe 1933-1945: Bericht über die unterirdische Arbeit gegen den Nationalsozialismus », dans Jahrbuch zur Konservative Revolution 1994 (Cologne : Anneliese Thomas, 1994), p. 329-34, ainsi que la description par Kluth (1980).

[48] Cf. Hielscher, Fünfzig Jahre, p. 402-26.

[49] Cf. Friedrich Hielscher, « Die Entwicklung », p. 3.

[50] Les textes se trouvent dans les documents Hielscher aux SBDA.

[51] Le matériel sur la cause et le cours des « crises de l’Église » qui furent liées à la scission peut être trouvé en grande quantité sous les mots-clés « 1. Kirchenkrise » et « 2. Kirchenkrise » dans les documents Hielscher aux SBDA. L’« Église Libre », qui fut dissoute dans les années 90, émergea de la « première crise » sous la direction du Dr. Rolf Kluth, directeur temporaire des Bibliothèques d’État et Universitaire de Brême et membre du cercle Hielscher depuis les années 30 ; en comparaison, la « seconde crise » ne conduisit pas à la formation d’un nouveau groupe, mais plutôt à l’implosion de l’UFK.

[52] Louis Pauwels et Jacques Bergier, Aufbruch ins dritte Jahrtausend : Von der Zukunft der phantastischen Vernunft, édition de poche (Munich, Heyne 1982), pp. 379-90. Ce matériel apparaît aux pp. 200-10 de l’édition américaine, publiée sous le titre de The Morning of the Magicians (New York, Stein & Day, 1963).

[53] Cf. Pauwels et Bergier, Aufbruch..., p. 389. Apparaît à la p. 206 de l’édition américaine.

[54] Ici le travail classique de Kater (1974) doit être cité en particulier. Cette histoire bien documentée de l’Ahnenerbe, cependant, est limitée par la large omission d’une analyse des projets de recherche spécifiques menés par l’Ahnenerbe, que ce soit dans le domaine de l’histoire intellectuelle ou dans celui des développements technologiques spécifiques.

[55] Cf. Pauwels et Bergier, Aufbruch , p. 389. Apparaît à la p. 206 de l’édition américaine.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Cf. Hielscher, Fünfzig Jahre, pp. 115-17.

[59] Cf. Hielscher, Fünfzig Jahre, p. 115.

[60] Lettre dans les documents Friedrich Georg Jünger aux Archives de Littérature Allemande.

[61] Cf. Pauwels et Bergier, Aufbruch..., p. 390. Apparaît à la p. 207 de l’édition américaine.

[62] Cf. Trevor Ravenscroft, Die heilige Lanze : Der Speer von Golgotha, 2° éd. (Munich, Universitas 1996), p. 265. Apparaît à la p. 259 de l’édition américaine de The Spear of Destiny (New York, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1973).

[63] Ibid.

[64] Ibid.

[65] The Spear of Destiny parut originellement en Grande-Bretagne en 1972 et ne fut pas traduit en allemand avant 1988 !

[66] Cf. Gerald Suster, Hitler : Black Magician, 2° éd. (Londres, Skoob, 1996), p. 182.

[67] Cf. Suster, Hitler, p. 184.

[68] Cf. Suster, Hitler, pp. 211-12.

[69] Cf. E.R. Carmin, Das Schwarze Reich : Geheimgesellschaften und Politik im 20. Jahrhundert, édition de poche (Munich, Heyne 1997), pp. 143, 701.

[70] Cf. Carmin, Das Schwarze Reich, p. 700.

[71] Cf. Miguel Serrano, Das Goldene Band: Esoterischer Hitlerismus, German edition (Wetter, Teut-Verlag 1987), p. 245.

[72] Cf. Serrano, Das Goldene Band, p. 373-98.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

NOUS APPELONS TES LOUPS

Nous appelons tes loups

Et appelons ta lance

Nous appelons les Douze

A descendre du ciel jusqu’à nous.

Avant tout nous t’appelons Toi.

Maintenant vient la chasse sauvage,

Maintenant que la corne retentisse,

Pour que les morts ne se lamentent pas.

L’ennemi est tombé

Avant le lever du jour.

La proie n’a pas de nom,

L’ennemi n’a pas de visage,

La carcasse pas de descendance,

Juste est le tribunal.

La moisson est passée,

La paille est vendue chaque jour,

Les corbeaux maintenant réclament

La part qui leur est due.

La chasse a commencé :

Maintenant, Seigneur, ton salut

Nous soutient !

- Friedrich Hielscher

(traduit de l’allemand en anglais par Gerhard et Michael Moynihan)

Article paru dans la revue américaine « TYR », volume 2, 2003-2004 (publiée par Joshua Buckley et Michael Moynihan ; un numéro par an).

Spanuth's approach to Atlantis was professional, as a classical scholar he had access to many ancient inscriptions, writings and fragments (especially Greek) and his expertise in this field meant he could quote and examine them in great detail. His original book 'Atlantis the mystery unravelled' was the most comprehenesive containing a massive amount of referenced classical sources. The purpose of Atlantis of the North (as the introduction states on the first few pages) was merely to be a ''shorter version'' of the original, for better access and understanding for the reader. There are still hundreds of classical sources however found cited throughout the book.

Spanuth's approach to Atlantis was professional, as a classical scholar he had access to many ancient inscriptions, writings and fragments (especially Greek) and his expertise in this field meant he could quote and examine them in great detail. His original book 'Atlantis the mystery unravelled' was the most comprehenesive containing a massive amount of referenced classical sources. The purpose of Atlantis of the North (as the introduction states on the first few pages) was merely to be a ''shorter version'' of the original, for better access and understanding for the reader. There are still hundreds of classical sources however found cited throughout the book.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Au début du mois de juillet 1942, tout semblait accréditer que la Wehrmacht allemande courait à la victoire définitive: l’Afrika Korps de Rommel venait de prendre Tobrouk et se trouvait tout près d’El Alamein donc à 100 km à l’ouest du Canal de Suez; au même moment, les premières opérations de la grande offensive d’été sur le front de l’Est venaient de s’achever avec le succès escompté: la grande poussée en avant en direction des champs pétrolifères de Bakou pouvait commencer. Tout cela est bien connu.

Au début du mois de juillet 1942, tout semblait accréditer que la Wehrmacht allemande courait à la victoire définitive: l’Afrika Korps de Rommel venait de prendre Tobrouk et se trouvait tout près d’El Alamein donc à 100 km à l’ouest du Canal de Suez; au même moment, les premières opérations de la grande offensive d’été sur le front de l’Est venaient de s’achever avec le succès escompté: la grande poussée en avant en direction des champs pétrolifères de Bakou pouvait commencer. Tout cela est bien connu.