Patrick De Vos

Ex: http://www.dewitteraaf.be

Het cordon sanitaire mag het VB (Vlaams Blok/Vlaams Belang) dan al verhinderen om aan het bestuur deel te nemen, de probleemstellingen, thema's en ideeën van het VB zijn uitgegroeid tot de common sense van het politieke denken in Vlaanderen en België. [1] In België is het VB daarmee het meest succesvolle politieke project van de voorbije 15 jaar; in heel Europa is het inmiddels de sterkste partij in haar soort geworden. Het oogst daarvoor aanzien in rechtse kringen over het hele continent.

Zoveel electorale voorspoed en ideologische impact stemt tot nadenken over de manier waarop we nu al jaren met die partij omgaan. In dat verband is het vreemd dat een Belgische politieke theoretica die ons daarbij kan helpen, de in Londen docerende Chantal Mouffe, in haar geboorteland, waar de problematiek wellicht het acuutst is, nagenoeg onbekend blijft. Als coauteur (met Ernesto Laclau) van het in 1985 verschenenHegemony and Socialist Strategy, en als auteur van The Return of the Political (1993), The Democratic Paradox(2000) en On the Political (2005), geniet zij bij een Anglo-Amerikaans, Latijns-Amerikaans, Frans en Duits lectoraat bekendheid om haar radicale en vernieuwende kijk op democratie.

Het werk van Laclau en Mouffe vind je binnen de politieke en sociale wetenschappen onder de noemer postmarxisme: de recentste telg van de marxistische stamboom, waarvan ook de sociaal-democratie, althans in principe, nog altijd een tak is. Laclau en Mouffe zijn kinderen van hun tijd: ‘68-ers die met het links-radicale denken zijn opgegroeid. Mouffe ging meteen na haar studies in Leuven naar Parijs om er bij de structuralist-marxist Louis Althusser te studeren. Daarna trok ze, als velen van haar generatie, naar de derde wereld. In Columbia werd haar al snel duidelijk dat althusseriaanse concepten, om het minste te zeggen, maar beperkt bruikbaar waren.

Rond 1970 radicaliseerde ook de Latijns-Amerikaanse studentenbeweging, aangemoedigd door de Cubaanse revolutie. Aan de Universiteit van Buenos Aires is de jonge marxist Ernesto Laclau politiek erg actief. Maar met de dogma’s van het marxisme worstelde hij toen al. Onder invloed van het Peronisme wou hij het marxisme met iets anders vermengen. Met hun lezing van de Italiaanse marxist Antonio Gramsci zullen Laclau en Mouffe uiteindelijk breken met het essentialisme en economisme van marxisten als Althusser en Poulanzas. In hun postmarxisme integreren zij de liberale notie van individuele rechten. De sociale horizon van hun politieke project is een radicale en pluralistische democratie. Het moet de doelstelling van Links zijn om de Democratische Revolutie, die tweehonderd jaar geleden geïnitieerd werd, te verdiepen en uit te breiden naar steeds meer gebieden van het sociale leven, steeds meer maatschappelijke sferen. Dat is wat ze bedoelen met “de radicalisering van de democratie”.

Daarnaast verwijderen Laclau en Mouffe het klassebegrip en de klassestrijd uit het marxisme. [2] De arbeidersklasse is niet langer de geprivilegieerde agent van de geschiedenis, en de strijd tegen het kapitalisme is niet noodzakelijk acuter dan die tegen racisme, seksisme of andere vormen van onderdrukking. Als we morgen alle kapitalistische productieverhoudingen afschaffen – voor zover dat al mogelijk is – dan zijn alle vormen van ongelijkheid en onderdrukking nog niet de wereld uit. [3] Wie de arbeider als geprivilegieerde politieke actor van de geschiedenis blijft zien, zal onder feministen of ecologisten weinig bondgenoten vinden. Hun politieke strijd is vanuit zo’n optiek immers van ondergeschikt belang. Laclau en Mouffe ontdoen het socialisme van deze essentialismen en effenen zodoende het pad om het, samen met feminisme, ecologisme, antiracisme, andersglobalisme enzovoort, tot een nieuw links project te articuleren. We spreken midden jaren ‘80 toen in de Britse context, waar ze inmiddels werkten, het thatcherisme pas goed op dreef kwam.

De liberale democratietheorie

Historisch gezien is onze democratie gegroeid uit de combinatie van twee vormgevende principes. Ten eerste de zogenaamde rule-of-law, die geassocieerd wordt met liberalisme, scheiding der machten, individuele vrijheden en mensenrechten. Elke burger komen onvervreemdbare, fundamentele rechten toe, die grondwettelijk verankerd zijn, en die de bescherming garanderen van de integriteit en de vrijheid van het individu. Deze ideeën passen in een liberale denktraditie die teruggaat tot de 17de-eeuwse Engelse filosoof John Locke. “All men are born free and equally alike”, zei Locke: dat is hun natuurlijke staat.

Ten tweede is er de notie van de volkssoevereiniteit, die geassocieerd wordt met democratische participatie, formele gelijkheid tussen burgers en het beslissen bij meerderheid. Hier staat de gedachte centraal dat het volk zichzelf bestuurt; een gedachte die teruggaat tot de Griekse stadstaat en die in de moderne tijd terugkeert bij de 18de-eeuwse Franse filosoof Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Deze twee principes vormen geen eeneiige tweeling. Tussen beide heerst een onherleidbare spanning, die Mouffe “de democratische paradox” noemt. Er is bijvoorbeeld een spanning tussen het liberale principe van individuele rechten en de nood van elke democratische samenleving aan sociale en politieke eenheid. Niet-negotieerbare mensenrechten (liberalisme) beperken onvermijdelijk de volkssoevereiniteit (democratie), terwijl de in- en uitsluiting aan de hand waarvan bepaald wordt wie er wel en niet tot de demos behoort (democratie) aan de universele mensenrechten (liberalisme) noodzakelijk beperkingen oplegt. Er is immers geen garantie dat een democratische beslissing de individuele rechten en vrijheden niet op het spel zet.

Hoewel we vandaag onder democratie, als vanzelfsprekend, liberale democratie verstaan, gaat het dus om een articulatie van twee verschillende tradities: de liberale traditie van individuele vrijheid en pluralisme, en de democratische traditie van volkssoevereiniteit en gelijkheid. Liberalisme is geen homogene doctrine, maar een amalgaam van principes: de rechtsstaat, individuele vrijheden en rechten, de erkenning van sociaal-politiek pluralisme, representatief bestuur, de scheiding der machten, limitatie van de staatsmacht, de kapitalistische markteconomie. Democratie, van haar kant, ontstond als een vertoog over volkssoevereiniteit, universeel stemrecht en gelijkheid.

In oorsprong waren liberalisme en democratie oppositioneel, en had de term democratie zelfs een pejoratieve betekenis: de heerschappij van het gepeupel, en dus chaos. Beide beginselen werden voor het eerst samen gearticuleerd in de 19de eeuw, wat er op den duur voor gezorgd heeft dat het liberalisme gedemocratiseerd en de democratie geliberaliseerd werd. Dit gebeurde door een opeenvolging van politieke conflicten, waarbij de ene traditie telkens weer haar suprematie over de andere wil doen gelden. Lange tijd werd dat conflict als legitiem beschouwd; pas in de voorbije decennia werd het als achterhaald van de hand gewezen. Maar volgens Mouffe bestaat er tussen de liberale principes van pluralisme, individualisme en vrijheid, en de democratische principes van eenheid, gemeenschap en gelijkheid, nog altijd een aanhoudende spanning, die in de huidige democratische theorie en praktijk verwaarloosd wordt. Het is deze onoplosbare spanning die de democratie levendig houdt en het primaat van de politiek garandeert, zegt Mouffe.

Traditioneel wordt democratie door de liberale theorie opgevat als een aggregatie van belangen. Dit model werd in de voorbije decennia wat verdrongen door het model van de deliberatieve democratie, dat politiek ziet in ethische en doorgaans universele termen, en dat verdedigd wordt door onder anderen Jürgen Habermas, John Rawls en Ronald Dworkin. Volgens hen is de democratische samenleving gericht op de creatie van een rationele consensus, die bereikt wordt aan de hand van deliberatieve processen die tegemoetkomen aan de belangen vaniedereen. Een beslissing is democratisch wanneer, na het voeren van een redelijke deliberatie, tussen álle betrokkenen een overeenstemming wordt bereikt. In dit denken domineren consensus en compromis, verkregen door rationele argumentatie en overtuiging.

Kenmerkend voor het individualistisch rationalisme van deze liberale democratieopvatting is het onvermogen om de specifieke aard van het politieke, en de formatie van politieke identiteiten die daarmee gepaard gaat, ten gronde te begrijpen. De idee van een perfecte consensus – of een harmonieuze collectieve wil, zoals bij Rousseau – wijst Mouffe als gevaarlijk van de hand. [4] Het liberale pluralisme wordt gekenmerkt door eindeloze conflicten tussen verschillende opinies en opvattingen inzake de ‘correcte’ interpretatie van vrijheid en gelijkheid. Het is deze aanhoudende onenigheid die mensen opdeelt in vrienden en vijanden. Als liberale denkers het collectieve karakter van de politieke strijd, die door het pluralisme bevorderd wordt, niet zien, dan komt dat door hun individualistische opvatting van politiek, als het rationeel nastreven en onderhandelen van individueel eigenbelang.

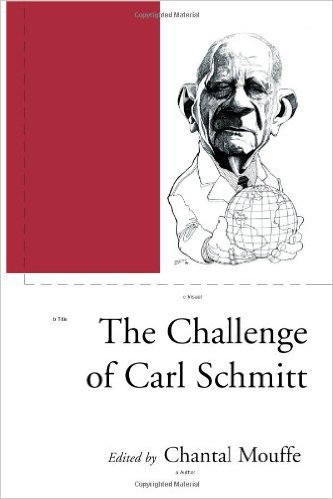

Net als Carl Schmitt (1888-1985) voert Chantal Mouffe de differentia specifica van het politieke terug op het onderscheid tussen vriend en vijand; oftewel tot de altijd aanwezige mogelijkheid van vijandelijkheid in intermenselijke relaties. Mouffe zegt niet dat alle sociale relaties noodzakelijk antagonistisch zijn, maar dat de mogelijkheid van conflict en vijandigheid in elke relatie op elk moment aanwezig is. Het politieke heeft altijd te maken met conflict en antagonisme, het gaat altijd gepaard met de formatie van een ‘wij’ versus een ‘zij’. In de discourstheorie van Laclau en Mouffe heet dit equivalentielogica: het opdelen van de sociale ruimte door betekenissen en identiteiten te comprimeren tot twee antagonistische polen.

Net als Carl Schmitt (1888-1985) voert Chantal Mouffe de differentia specifica van het politieke terug op het onderscheid tussen vriend en vijand; oftewel tot de altijd aanwezige mogelijkheid van vijandelijkheid in intermenselijke relaties. Mouffe zegt niet dat alle sociale relaties noodzakelijk antagonistisch zijn, maar dat de mogelijkheid van conflict en vijandigheid in elke relatie op elk moment aanwezig is. Het politieke heeft altijd te maken met conflict en antagonisme, het gaat altijd gepaard met de formatie van een ‘wij’ versus een ‘zij’. In de discourstheorie van Laclau en Mouffe heet dit equivalentielogica: het opdelen van de sociale ruimte door betekenissen en identiteiten te comprimeren tot twee antagonistische polen.

Antagonisme is het sleutelwoord om de vorming van politieke identiteit te begrijpen. Anders dan de traditionele notie van sociaal antagonisme – dit is een confrontatie tussen sociale agenten die reeds beschikken over een volledig ontwikkelde identiteit – beweren Laclau en Mouffe dat antagonismen juist voorkomen omdat wij, als sociale agenten, niet bij machte zijn onze identiteit volledig te ontwikkelen. Zij steunen daarvoor in hoofdzaak op de lacaniaanse psychoanalyse en de derridiaanse notie van een constitutieve buitenkant, als voorwaarde voor de constructie van elke identiteit. Eenvoudig gesteld: een antagonisme ontstaat wanneer de aanwezigheid van ‘de Andere’ mij verhindert om volledig mezelf te zijn. [5] Deze blokkade is een wederzijdse ervaring. [6] Antagonismen onthullen niet alleen het tekort aan identiteit van sociale agenten, zij geven vorm aan de sociale werkelijkheid als zodanig. Sociale formaties worden gevormd aan de hand van antagonistische relaties, waardoor zich tussen sociale agenten politieke breuklijnen vestigen en verschillende identificaties vorm aannemen. [7]

Een democratie behoort pluraal te zijn. Op dat punt is Mouffe het eens met de liberale theorie. Zij betwist evenmin dat een plurale democratie een minimale consensus vereist over gemeenschappelijke ethisch-politieke principes. Maar consensus alleen volstaat niet. Zij is slechts het resultaat van een onderhandeling die telkens weer gevoerd moet worden. In de liberale democratieopvatting ligt de focus op het resultaat van consensus, die bereikt wordt door rationele compromisvorming tussen subjecten met een stabiele en gepreconfigureerde identiteit. Politiek wordt als een neutraal terrein gezien waarop verschillende groepen strijden om politieke macht. De politiek is als een schaakspel waarvan de spelregels en limieten vastliggen. Voor Mouffe daarentegen, gaat het er juist om de regels van de politiek te herschrijven. Het politieke terrein is niet neutraal. Het is in zekere zin de inzet van politieke strijd; in die strijd zelf wordt het terrein gevormd of hervormd.

Liberalism forever!

Sinds de val van de Berlijnse Muur domineert het in oorsprong thatcheriaanse denkbeeld dat er voor de huidige liberaal-kapitalistische wereldorde geen alternatief bestaat. Het failliet van het reëel bestaande socialisme betekende de definitieve overwinning van het kapitalisme en de liberale democratie: dat was de these van Francis Fukuyama, de Amerikaanse politicoloog en adviseur van Ronald Reagan. [8] Het liberalisme had die overwinning volgens hem te danken aan het feit dat het zowel op het materiële vlak (kapitalistisch marktmechanisme) als op het niet-materiële vlak (individuele erkenning) een maximale bevrediging biedt. Uit een hegeliaanse analyse van de geschiedenis haalt Fukuyama het ‘bewijs’ voor de afwezigheid van samenhangende alternatieven voor het liberalisme. De geschiedenis, als voortdurende strijd tussen politieke ideologieën en statenstelsels, heeft haar eindtermen bereikt: “liberalism forever!”

Het einde van de geschiedenis is een wat filosofische uitdrukking die staat voor het einde van de politiek, en Fukuyama was niet de eerste die deze stelling verdedigde. Om te beginnen was er Hegel zelf die in 1806, na de overwinning van Napoleon in de slag bij Jena, verklaarde dat de geschiedenis aan haar einde was gekomen. Begin jaren ‘60 initieerde de Harvardsocioloog Daniel Bell het debat over het einde van de grote ideologische conflicten. In de welvarende samenlevingen van het westen, aldus Bell, is de voorraad aan politieke ideeën uitgeput en zijn ideologische vraagstukken irrelevant geworden. Er is een brede ideologische consensus ontstaan, met als gevolg dat politieke partijen enkel nog om de macht strijden door hun electoraat meer welvaart te beloven. Volgens Bell zegevierde het economische dus ook over het politieke. Maar de heropleving van politiek-ideologische tegenstellingen en de politieke radicalisering van mei ‘68 haalden zijn these onderuit.

De clou bij dit soort politieke eschatologie is de volgende. Politieke ideologieën zijn supra-individuele denkvormen waardoor sociale actoren en groupe zin en richting geven aan hun maatschappelijk bestaan. Ze zijn naast descriptief altijd ook normatief. Ze willen vormgeven aan (toekomstige) sociale verhoudingen en bijgevolg zijn ze op handelen gericht. Elke politieke ideologie heeft de ambitie sociaal te interveniëren (decision making) of zo’n interventie te verhinderen (non-decision making). Deze toekomstgerichtheid vereist een sociale horizon (of sociale utopie) die het resultaat belooft te zijn van dat politieke project.

Elke politieke ideologie houdt dus de belofte in dat ze, met de realisatie van haar project, een eind zal maken aan de politiek. Het was Friedrich Engels die de stelling van Claude Henri de Saint-Simon overnam dat het heersen over mensen in de klassenloze maatschappij – de sociale horizon van het socialistische project – plaats zal maken voor het beheer van zaken. “Goed bestuur”, zeggen we vandaag. En het was de Italiaanse nationalist Giuseppe Mazzini (1805-1872) die stelde dat, als elke natie, separaat en distinct, een volwaardige organische eenheid zal zijn, er geen reden meer is voor onderling conflict. Macht en geweld zijn nodig om de oude orde aan de kant te zetten, maar eens de wereld volgens de nationalistische doctrine van één taal, één volk en één natie geordend zal zijn, wordt oorlog overbodig. [9]

Elk politiek project belooft dat, met de volledige realisatie van haar utopie, politiek overbodig wordt. Het is in die geest van het einde der tijden en het laatste oordeel dat Fukuyama de superioriteit van de liberaal-democratische staatsordening en van het kapitalistisch economisch systeem als bewezen proclameert. Nochtans was zijn these onder meer op feitelijke onjuistheden gebaseerd. Niet het liberalisme ‘pur sang’ had de Koude Oorlog overleefd, maar een gemengd model dat het laisser-fairebeginsel van de vrije markt compenseert door staatstussenkomst, regulatie en herverdeling. In de moderne geschiedenis heeft er nooit een volledig vrije markt bestaan, en dit geldt zelfs voor die landen waar het politieke liberalisme op dat moment hoogtij vierde: het Amerika van Reagan en Bush Senior en het Engeland van Thatcher en Major. Alle sterke, geïndustrialiseerde landen zijn sterk geworden door een mix van laisser faire en staatsinterventie. Ook hier zien we dat het principe van de vrije markt op gespannen voet staat met de democratie: de markt genereert ongelijkheid, die vervolgens door staatsinterventie gecompenseerd wordt. Op dat punt is er geen finale, rationele consensus mogelijk. Het economisch liberalisme is een moderne theorie van de ongelijkheid, zoals de vertegenwoordigende democratie een moderne theorie van de gelijkheid is. Het dispuut over de juiste verhouding tussen markt en staat is inherent aan de liberaal-democratische samenleving. [10]

Wat een radicale democratie à la Laclau en Mouffe onderscheidt van de moderne politieke projecten, is dat ze niet van een realiseerbare telos uitgaat, maar van het besef dat elk sociaal project onvolmaakt en conflictueel zal blijven. Het streven naar een volledig democratische maatschappij, waarin alle mensen volledig vrij zijn omdat ze volledig gelijk zijn, en vice versa, veronderstelt een volledige transparantie. Het veronderstelt een samenleving zonder spanningen en repressie, die dus alle conflicten onderdrukt. [11] Zo’n harmonieuze democratie zou een totalitaire nachtmerrie zijn. Bij Laclau en Mouffe wordt de mogelijkheid om het finale doel te realiseren verlaten, zelfs als louter regulatief idee. Er is trouwens geen reden om dat te betreuren. Integendeel, het is de garantie dat het democratisch-pluralistisch proces aan de gang blijft. Het is door de liberale rechten samen met volkssoevereiniteit te articuleren, dat we vermijden dat de democratie tiranniek wordt. Een ideale, vrije en gelijke democratische samenleving is er noodzakelijk een zonder pluralisme, want pluralisme veronderstelt dat de sociale orde en haar machtsrelaties kunnen worden gecontesteerd. Een samenleving zonder machtsrelaties (het einde van de politiek) is evenmin mogelijk, want het zijn precies de machtsrelaties die de sociale orde constitueren. Laclau en Mouffe vertrekken dus van een niet-reduceerbare, pluralistische sociale orde; en dit betekent dat de finale sociale orde nooit bereikt wordt. Niet alleen de individuen verkeren in de onmogelijkheid om hun identiteiten te finaliseren; ook de samenleving als zodanig is nooit af.

Wat een radicale democratie à la Laclau en Mouffe onderscheidt van de moderne politieke projecten, is dat ze niet van een realiseerbare telos uitgaat, maar van het besef dat elk sociaal project onvolmaakt en conflictueel zal blijven. Het streven naar een volledig democratische maatschappij, waarin alle mensen volledig vrij zijn omdat ze volledig gelijk zijn, en vice versa, veronderstelt een volledige transparantie. Het veronderstelt een samenleving zonder spanningen en repressie, die dus alle conflicten onderdrukt. [11] Zo’n harmonieuze democratie zou een totalitaire nachtmerrie zijn. Bij Laclau en Mouffe wordt de mogelijkheid om het finale doel te realiseren verlaten, zelfs als louter regulatief idee. Er is trouwens geen reden om dat te betreuren. Integendeel, het is de garantie dat het democratisch-pluralistisch proces aan de gang blijft. Het is door de liberale rechten samen met volkssoevereiniteit te articuleren, dat we vermijden dat de democratie tiranniek wordt. Een ideale, vrije en gelijke democratische samenleving is er noodzakelijk een zonder pluralisme, want pluralisme veronderstelt dat de sociale orde en haar machtsrelaties kunnen worden gecontesteerd. Een samenleving zonder machtsrelaties (het einde van de politiek) is evenmin mogelijk, want het zijn precies de machtsrelaties die de sociale orde constitueren. Laclau en Mouffe vertrekken dus van een niet-reduceerbare, pluralistische sociale orde; en dit betekent dat de finale sociale orde nooit bereikt wordt. Niet alleen de individuen verkeren in de onmogelijkheid om hun identiteiten te finaliseren; ook de samenleving als zodanig is nooit af.

Politiek zonder ware tegenstanders

Dit plurale en onvoltooibare van elke samenleving wordt door de consensuspolitiek van het centrum verdoezeld; en het is tegen die achtergrond dat we volgens Chantal Mouffe het succes van rechts-populistische partijen kunnen begrijpen. In nagenoeg dezelfde periode waarin het VB in Vlaanderen opgang maakt, bewegen de traditionele partijen naar het centrum, en claimen daar de zogenaamde Derde Weg. Toen New Labour op 1 mei 1997 de Britse verkiezingen won, nam het toenmalige BRTN-journaal de proef op de som. Het vroeg de partijvoorzitters van de drie grootste Vlaamse partijen, onafhankelijk van elkaar, om commentaar te geven bij deze gebeurtenis. Eén voor één verklaarden ze op dezelfde lijn te zitten als Tony Blair: de christen-democraten vonden dat ze altijd al de gulden middenweg van Blair hadden bewandeld; de liberalen zegden dat zij, net als Blair, de grote politieke vernieuwers van hun generatie waren; en de sociaal-democraten zagen in de verkiezingsoverwinning van Blair een bevestiging van de vernieuwingsbeweging in heel de Europese sociaal-democratie.

De ideologische tegenstellingen tussen de gevestigde partijen is in de loop van het laatste decennium alsmaar kleiner geworden, waardoor het steeds moeilijker is om partijen en politici in hun optreden en standpunten te onderscheiden. Ideologische beginselen boeten aan belang in, terwijl politiek pragmatisme en consensuspolitiek op de voorgrond treden. In de consensuspolitiek van het centrum, zegt ook de Sloveense filosoof Slavoj Zizek, moet elke fundamentele belangentegenstelling plaats ruimen voor een vrijmoedig geloof in een politiek zonder ware tegenstanders, en zonder enige subversiviteit. [12] Eens beyond left and right lossen sociale tegenstellingen vanzelf op en bieden er zich politieke oplossingen aan die kennelijk voor iedereen goed zijn. Bij gebrek aan een reële politieke strijd, onderscheiden politieke partijen zich enkel nog door culturele attitudes. De politieke strijd wordt herleid tot een belangencompetitie op neutraal terrein, met als enige doel het bereiken van compromissen en het aggregeren van voorkeuren. Om fundamentele belangenconflicten te omzeilen, weigert men om duidelijke politieke grenzen te trekken. Daarmee wordt de integratieve rol van conflict in de moderne democratie genegeerd. [13]

De ideologische tegenstellingen tussen de gevestigde partijen is in de loop van het laatste decennium alsmaar kleiner geworden, waardoor het steeds moeilijker is om partijen en politici in hun optreden en standpunten te onderscheiden. Ideologische beginselen boeten aan belang in, terwijl politiek pragmatisme en consensuspolitiek op de voorgrond treden. In de consensuspolitiek van het centrum, zegt ook de Sloveense filosoof Slavoj Zizek, moet elke fundamentele belangentegenstelling plaats ruimen voor een vrijmoedig geloof in een politiek zonder ware tegenstanders, en zonder enige subversiviteit. [12] Eens beyond left and right lossen sociale tegenstellingen vanzelf op en bieden er zich politieke oplossingen aan die kennelijk voor iedereen goed zijn. Bij gebrek aan een reële politieke strijd, onderscheiden politieke partijen zich enkel nog door culturele attitudes. De politieke strijd wordt herleid tot een belangencompetitie op neutraal terrein, met als enige doel het bereiken van compromissen en het aggregeren van voorkeuren. Om fundamentele belangenconflicten te omzeilen, weigert men om duidelijke politieke grenzen te trekken. Daarmee wordt de integratieve rol van conflict in de moderne democratie genegeerd. [13]

Want het specifieke van een democratie schuilt niet zozeer in haar formele procedures – zoals verkiezingen of de parlementaire stemrondes – maar in haar erkenning van de legitimiteit van sociaal conflict, en haar afwijzing van de autoritaire onderdrukking ervan. [14] Democratie is meer dan een populariteitspoll. Wat een samenleving werkelijk democratisch maakt, is dat ze plaats ruimt voor de expressie van conflicterende belangen en waarden; of anders gezegd, dat zij de voorwaarden schept die antagonistische confrontatie mogelijk maken. Alleen dan leeft die democratie. Het onvermogen om dat in te zien, zegt Mouffe, is zonder meer de belangrijkste tekortkoming van de consensuspolitiek. De reële keuzemogelijkheid die een democratie haar burgers behoort te bieden, is als gevolg van het sacraliseren van de consensus in feite verdwenen. Daardoor kunnen belangrijke politieke sentimenten niet meer worden uitgedrukt binnen het democratische systeem. Naast de nieuwe liberale orde is er geen plaats voor een debat over mogelijke alternatieven; er is geen ruimte voor andere identificatiemodellen waarrond mensen kunnen worden gemobiliseerd. En daardoor winnen andere vormen van politieke identificatie terrein: vormen die met de democratie nauwelijks verzoenbaar zijn – zoals rechts-extremisme en religieus fundamentalisme. [15] Het succes van populistisch rechts, zegt Zizek, is de prijs die de linkerzijde betaalt voor het verloochenen van elk radicaal politiek project en voor het aanvaarden van het kapitalisme als een fait accompli. [16]

Dienen we de kritiek van Chantal Mouffe op te vatten als een ultieme oproep om het cordon sanitaire in Vlaanderen dan toch maar op te doeken? Dat valt te betwijfelen. Waar het Mouffe om te doen is, is laten zien wat het ons heeft opgeleverd, om daaruit conclusies te trekken. Het probleem is overigens niet dat mensen uit zijn op conflict omwille van het conflict. Het probleem is dat, door het gebrek aan een sociale horizon, bepaalde sentimenten geen uitdrukking vinden binnen het democratisch spectrum. Deze sentimenten moeten democratisch gemobiliseerd worden; en daarvoor moeten de democratische partijen een sociale horizon projecteren die mensen uitzicht biedt op een andere en betere toekomst.

Dienen we de kritiek van Chantal Mouffe op te vatten als een ultieme oproep om het cordon sanitaire in Vlaanderen dan toch maar op te doeken? Dat valt te betwijfelen. Waar het Mouffe om te doen is, is laten zien wat het ons heeft opgeleverd, om daaruit conclusies te trekken. Het probleem is overigens niet dat mensen uit zijn op conflict omwille van het conflict. Het probleem is dat, door het gebrek aan een sociale horizon, bepaalde sentimenten geen uitdrukking vinden binnen het democratisch spectrum. Deze sentimenten moeten democratisch gemobiliseerd worden; en daarvoor moeten de democratische partijen een sociale horizon projecteren die mensen uitzicht biedt op een andere en betere toekomst.

De opkomst van extreem-rechts heeft voor Mouffe dus in eerste instantie te maken met het gebrek aan hoop dat het democratisch systeem ons vandaag biedt. Als mensen niet langer geïnteresseerd zijn in politiek, of hun toevlucht nemen tot intolerante en fundamentalistische groeperingen, dan komt dat in hoofdzaak omdat de democratische partijen hen te weinig solide alternatieven bieden. Het liberale consensusdenken verhindert dat we de rol van non-rationele factoren – zoals sentimenten, dromen, passie, fantasie, verlangen, ontgoocheling en hoop – goed begrijpen. Mouffe beschouwt deze individueel verankerde motivaties als een drijvende politieke kracht. “I had a dream”, zei Martin Luther King. Hij zei niet dat hij een oplossing had bedacht, een rationele consensus die het conflict van de baan zou helpen. Rationalisme is altijd ook een obstakel om de conflictuele aard van de politiek te begrijpen.

De Amerikaanse socioloog Immanuel Wallerstein vroeg zich ooit af waarom de armen het tolereren dat de rijken rijker worden, terwijl zijzelf armer worden. [17] Volgens hem hebben zij dat de voorbije twee eeuwen voornamelijk getolereerd omdat zij geloofden dat er hoop was, en omdat zij verwachtten dat hun situatie zou verbeteren, dankzij politieke mechanismen zoals de sociaal-democratie en de welvaartsstaat. Maar hoop is niet alleen wat de armen nodig hebben. Hoop is altijd verbonden met iets wat afwezig is, en die absentie is iets wat we allemaal, in een of andere vorm, ervaren.

De notie van hoop is bij Chantal Mouffe verbonden met die van menselijke emancipatie. Als we ons als mens beknot voelen in onze potentiële ontwikkeling, creëren we een soort toekomstbeeld waarin we die limitaties overstijgen. In een situatie van radicale wanorde en machtswillekeur, bijvoorbeeld, wordt de voorstelling van een ordelijke maatschappij een sociale utopie. Zo’n denkbeeld, waaruit we hoop putten, geeft richting aan ons streven. Hoop is wat onze sociale horizon voedt. Die hoop is onuitroeibaar; maar zij kan op verschillende manieren en in verschillende richtingen gemobiliseerd worden. Wanneer de democratie er zelf geen ruimte voor schept, door fundamentele dissensus toe te laten, dan zal zij zich uiten op een negatieve manier: als een proteststem bijvoorbeeld, een stem tégen de afwezigheid van hoop.

Het verwaarlozen van de antagonistische dimensie in de politiek, zorgt ervoor dat die hoop zich naar de rand van het politieke spectrum verplaatst. Dat is de belangrijkste oorzaak van de opkomst van extremistische groeperingen. En dit lijkt meteen ook de kern van Mouffes boodschap. De aantrekkingkracht van extreem-rechts is dat het wél een sociale horizon biedt, terwijl de gevestigde partijen doen alsof er geen fundamenteel alternatief mogelijk is. Maar omdat de sociale horizon van extreem-rechts geen plaats voor pluralisme biedt, bedreigt zij de liberale democratie en biedt zij ook geen ‘hoop’ in de ware zin van het woord – de zin die Mouffe eraan geeft. Mouffe ziet in de huidige politieke situatie een democratisch deficit: een samenleving die verstoken blijft van een dynamisch democratisch leven, met reële confrontaties rond een diversiteit van effectieve alternatieven, legt het terrein voor andere vormen van identificatie rond etnische, religieuze, nationalistische en soortgelijke problematische claims; claims waarmee het democratisch systeem uiteindelijk slecht gediend is. [18]

Noten

1 Zie Jan Blommaert, Blokspraak, in: De Witte Raaf nr. 114, maart-april 2005, pp. 1-3.

2 Ellen M. Wood, The Retreat from Class: the New ‘True Socialism’, London, Verso, 1986, p. 4.

3 Ernesto Laclau & Chantal Mouffe, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics, London, Verso, 1985, p. 192.

4 Chantal Mouffe, Radical Democracy or Liberal Democracy, in: Socialist Review, vol. 20 (2), 1990, pp. 58-59.

5 Laclau & Mouffe, op. cit. (noot 3), p. 125.

6 David Howarth & Yannis Stavrakakis, Discourse Theory and Political Analysis, in: David Howarth, Aletta J. Noval & Yannis Stavrakakis (red.), Discourse Theory and Political Analysis: Identities, Hegemonies and Social Change, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2000, p. 10.

7 David Howarth, Discourse Theory and Political Analysis, in: Elinor Scarbrough & Eric Tanenbaum (red.),Research Strategies in the Social Sciences: a Guide to New Approaches, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1998, p. 276; Howarth & Stavrakakis, op. cit. (noot 6), p. 11.

8 Francis Fukuyama, Het einde van de geschiedenis en de laatste mens, Amsterdam, Contact, 1992.

9 Peter J. Taylor, Political Geography: World-Economy, Nation-State and Locality, Harlow, Longman Scientific & Technical, 1993, p. 206.

10 Siep Stuurman, Het begin van de toekomst, in: Vrij Nederland, 9 oktober 1999.

11 Jacob Torfing, New Theories of Discourse: Laclau, Mouffe and Zizek, Oxford, Blackwell, 1999, p. 258.

12 Slavoj Zizek, Wat is het fijn om tegen Haider te zijn, in: Nieuw Wereldtijdschrift, vol. 17 (3), april 2000, pp. 43-45.

13 Chantal Mouffe, The Democratic Paradox, London, Verso, 2000, pp. 113-116.

14 Chantal Mouffe, The Radical Centre: a Politics Without Adversary, in: Soundings, nr. 9, zomer 1998, p. 13.

15 Chantal Mouffe, 10 Years of False Starts, in: New Times, 9 november 1999.

16 Zizek, op. cit. (noot 12), pp. 43-45.

17 Immanuel Wallerstein, geciteerd in: Bart Tromp, Het systeem kraakt, in: De Groene Amsterdammer, 3 december 1997.

18 Chantal Mouffe, op. cit. (noot 14), p. 13.

As war erupted in Europe in September 1939 with Hitler’s and Stalin’s dismemberment of Poland, European gold was flooding into the United States. In 1935 US official gold reserves had been valued at just over $9 billion. By 1940 after the onset of war in Europe, they had risen to $20 billion. As desperate European countries sought to finance their war effort, their gold went to the United States to purchase essential goods. By the time of the June 1944 convening of the international monetary conference at Bretton Woods, the United States controlled fully 70% of the world’s monetary gold, an impressive advantage. That 70% did not even include calculating the captured gold of the defeated Axis powers of Germany or Japan, where exact facts and data were buried in layers of deception and rumor.

As war erupted in Europe in September 1939 with Hitler’s and Stalin’s dismemberment of Poland, European gold was flooding into the United States. In 1935 US official gold reserves had been valued at just over $9 billion. By 1940 after the onset of war in Europe, they had risen to $20 billion. As desperate European countries sought to finance their war effort, their gold went to the United States to purchase essential goods. By the time of the June 1944 convening of the international monetary conference at Bretton Woods, the United States controlled fully 70% of the world’s monetary gold, an impressive advantage. That 70% did not even include calculating the captured gold of the defeated Axis powers of Germany or Japan, where exact facts and data were buried in layers of deception and rumor. French President Charles de Gaulle, acting on advice of his conservative financial adviser, Jacques Rueff, ordered the Bank of France to begin to redeem its rapidly accumulating trade surplus dollars for gold, something then legal under the rules of Bretton Woods. The conservative German Bundesbank followed in demanding US gold for dollars. In 1968 in one of the first crude versions of their Color Revolutions, the CIA and US State Department toppled President de Gaulle in the events known as the May 1968 student revolt. Despite the replacement of de Gaulle by former Rothschild banker, Georges Pompidou, the foreign demand for Federal Reserve gold redemptions increased as Washington budget deficits to finance the ill-conceived Vietnam War exploded.

French President Charles de Gaulle, acting on advice of his conservative financial adviser, Jacques Rueff, ordered the Bank of France to begin to redeem its rapidly accumulating trade surplus dollars for gold, something then legal under the rules of Bretton Woods. The conservative German Bundesbank followed in demanding US gold for dollars. In 1968 in one of the first crude versions of their Color Revolutions, the CIA and US State Department toppled President de Gaulle in the events known as the May 1968 student revolt. Despite the replacement of de Gaulle by former Rothschild banker, Georges Pompidou, the foreign demand for Federal Reserve gold redemptions increased as Washington budget deficits to finance the ill-conceived Vietnam War exploded. By August 1971, President Nixon was advised by his Assistant Treasury secretary, Paul Volcker, a former executive at Rockefeller’s Chase Manhattan Bank, to essentially tear up the Bretton Woods Treaty and declare the US dollar a free-floating paper no longer redeemable in gold. The Federal Reserve’s gold reserves over the previous several years had been drained by foreign central banks fearful of the import of US dollar inflation as Washington refused pleas to devalue the dollar to re-stabilize the system. Rueff and France were calling for a 100% dollar devaluation against the Franc or Deutschmark.

By August 1971, President Nixon was advised by his Assistant Treasury secretary, Paul Volcker, a former executive at Rockefeller’s Chase Manhattan Bank, to essentially tear up the Bretton Woods Treaty and declare the US dollar a free-floating paper no longer redeemable in gold. The Federal Reserve’s gold reserves over the previous several years had been drained by foreign central banks fearful of the import of US dollar inflation as Washington refused pleas to devalue the dollar to re-stabilize the system. Rueff and France were calling for a 100% dollar devaluation against the Franc or Deutschmark.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Here is where German intellectuals come into the story. Journalists and academics have had a hard time understanding why the Pegida movement emerged when it did and why it has attracted so many people in Germany; there are branches of the Pegida movement in other parts of Europe, but they have gathered only marginal support thus far. Those who suggest it is driven by “anger” and “resentment” are being descriptive at best. What is remarkable, though, is that “rage” as a political stance has received the philosophical blessing of the leading AfD intellectual, Marc Jongen, who is a former assistant of the well-known philosopher Peter Sloterdijk. Jongen has not only warned about the danger of Germany’s “cultural self-annihilation”; he has also argued that, because of the cold war and the security umbrella provided by the US, Germans have been forgetful about the importance of the military, the police, warrior virtues—and, more generally, what the ancient Greeks called thymos (variously translated as spiritedness, pride, righteous indignation, a sense of what is one’s own, or rage), in contrast to eros and logos, love and reason. Germany, Jongen says, is currently “undersupplied” with thymos. Only the Japanese have even less of it—presumably because they also lived through postwar pacifism. According to Jongen, Japan can afford such a shortage, because its inhabitants are not confronted with the “strong natures” of immigrants. It follows that the angry demonstrators are doing a damn good thing by helping to fire up thymos in German society.

Here is where German intellectuals come into the story. Journalists and academics have had a hard time understanding why the Pegida movement emerged when it did and why it has attracted so many people in Germany; there are branches of the Pegida movement in other parts of Europe, but they have gathered only marginal support thus far. Those who suggest it is driven by “anger” and “resentment” are being descriptive at best. What is remarkable, though, is that “rage” as a political stance has received the philosophical blessing of the leading AfD intellectual, Marc Jongen, who is a former assistant of the well-known philosopher Peter Sloterdijk. Jongen has not only warned about the danger of Germany’s “cultural self-annihilation”; he has also argued that, because of the cold war and the security umbrella provided by the US, Germans have been forgetful about the importance of the military, the police, warrior virtues—and, more generally, what the ancient Greeks called thymos (variously translated as spiritedness, pride, righteous indignation, a sense of what is one’s own, or rage), in contrast to eros and logos, love and reason. Germany, Jongen says, is currently “undersupplied” with thymos. Only the Japanese have even less of it—presumably because they also lived through postwar pacifism. According to Jongen, Japan can afford such a shortage, because its inhabitants are not confronted with the “strong natures” of immigrants. It follows that the angry demonstrators are doing a damn good thing by helping to fire up thymos in German society. Like in Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morality—a continuous inspiration for Sloterdijk—these re-descriptions are supposed to jolt readers out of conventional understandings of the present. However, not much of his work lives up to Nietzsche’s image of the philosopher as a “doctor of culture” who might end up giving the patient an unpleasant or outright shocking diagnosis: Sloterdijk often simply reads back to the German mainstream what it is already thinking, just sounding much deeper because of the ingenuous metaphors and analogies, cute anachronisms, and cascading neologisms that are typical of his highly mannered style.

Like in Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morality—a continuous inspiration for Sloterdijk—these re-descriptions are supposed to jolt readers out of conventional understandings of the present. However, not much of his work lives up to Nietzsche’s image of the philosopher as a “doctor of culture” who might end up giving the patient an unpleasant or outright shocking diagnosis: Sloterdijk often simply reads back to the German mainstream what it is already thinking, just sounding much deeper because of the ingenuous metaphors and analogies, cute anachronisms, and cascading neologisms that are typical of his highly mannered style.  Sloterdijk is not the only prominent cultural figure who willfully reinforces a sense of Germans as helpless victims who are being “overrun” and who might eventually face “extinction.” The writer Botho Strauβ recently published an essay titled “The Last German,” in which he declared that he would rather be part of a dying people than one that for “predominantly economic-demographic reasons is mixed with alien peoples, and thereby rejuvenated.” He feels that the national heritage “from Herder to Musil” has already been lost, and yet hopes that Muslims might teach Germans a lesson about what it means to follow a tradition—because Muslims know how to submit properly to their heritage. In fact, Strauβ, who cultivates the image of a recluse in rural East Germany, goes so far as to speculate that only if the German Volk become a minority in their own country will they be able to rediscover and assert their identity.

Sloterdijk is not the only prominent cultural figure who willfully reinforces a sense of Germans as helpless victims who are being “overrun” and who might eventually face “extinction.” The writer Botho Strauβ recently published an essay titled “The Last German,” in which he declared that he would rather be part of a dying people than one that for “predominantly economic-demographic reasons is mixed with alien peoples, and thereby rejuvenated.” He feels that the national heritage “from Herder to Musil” has already been lost, and yet hopes that Muslims might teach Germans a lesson about what it means to follow a tradition—because Muslims know how to submit properly to their heritage. In fact, Strauβ, who cultivates the image of a recluse in rural East Germany, goes so far as to speculate that only if the German Volk become a minority in their own country will they be able to rediscover and assert their identity.  Like at least some radicals in the late Sixties, the new right-wing “avant-garde” finds the present moment not just one of apocalyptic danger, but also of exhilaration. There is for instance Götz Kubitschek, a publisher specializing in conservative nationalist or even outright reactionary authors, such as Jean Raspail and Renaud Camus, who keep warning of an “invasion” or a “great population replacement” in Europe. Kubitschek tells Pegida demonstrators that it is a pleasure (lust) to be angry. He is also known for organizing conferences at his manor in Saxony-Anhalt, including for the “Patriotic Platform.” His application to join the AfD was rejected during the party’s earlier, more moderate phase, but he has hosted the chairman of the AfD, Björn Höcke, in Thuringia. Höcke, a secondary school teacher by training, offered a lecture last fall about the differences in “reproduction strategies” of “the life-affirming, expansionary African type” and the place-holding European type. Invoking half-understood bits and pieces from the ecological theories of E. O. Wilson, Höcke used such seemingly scientific evidence to chastise Germans for their “decadence.”

Like at least some radicals in the late Sixties, the new right-wing “avant-garde” finds the present moment not just one of apocalyptic danger, but also of exhilaration. There is for instance Götz Kubitschek, a publisher specializing in conservative nationalist or even outright reactionary authors, such as Jean Raspail and Renaud Camus, who keep warning of an “invasion” or a “great population replacement” in Europe. Kubitschek tells Pegida demonstrators that it is a pleasure (lust) to be angry. He is also known for organizing conferences at his manor in Saxony-Anhalt, including for the “Patriotic Platform.” His application to join the AfD was rejected during the party’s earlier, more moderate phase, but he has hosted the chairman of the AfD, Björn Höcke, in Thuringia. Höcke, a secondary school teacher by training, offered a lecture last fall about the differences in “reproduction strategies” of “the life-affirming, expansionary African type” and the place-holding European type. Invoking half-understood bits and pieces from the ecological theories of E. O. Wilson, Höcke used such seemingly scientific evidence to chastise Germans for their “decadence.”

Heel wat politici, filosofen en gewone burgers eisen van de overheid meer transparantie in het politiek bedrijf. Het lijkt wel het tovermiddel om onze democratie sterker en efficiënter te maken. En de politiek speelt daar ook op in. Nieuwe parlementsgebouwen worden gebouwd met grote glaspartijen als figuurlijk, maar ook letterlijk symbool van de gezamenlijke wil om te komen tot transparantie. Burgers krijgen zo bijna letterlijk inzage in de parlementaire werking en de verkozenen van het volk zien als het ware hoe de burgers op hen toekijken. Dus geen beslissingen meer in duistere achterkamertjes maar openbare debatten die dan via televisie en het internet gevolgd kunnen worden door al wie interesse heeft. Transparantie wordt ook geëist van zowat alle burgers om aan te tonen dat ze ‘niets te verbergen hebben’ en daarom figuurlijk doorzichtig moeten zijn. Leve de transparantie dus. Maar tegen die trend in schreef de Nederlandse hoogleraar Bestuurskunde Paul Frissen het boek Het geheim van de laatste staat waarin hij kritiek geeft op de transparantie en pleit voor het fundamentele recht van de burger op geheimen als één van de waarborgen van zijn vrijheid.

Heel wat politici, filosofen en gewone burgers eisen van de overheid meer transparantie in het politiek bedrijf. Het lijkt wel het tovermiddel om onze democratie sterker en efficiënter te maken. En de politiek speelt daar ook op in. Nieuwe parlementsgebouwen worden gebouwd met grote glaspartijen als figuurlijk, maar ook letterlijk symbool van de gezamenlijke wil om te komen tot transparantie. Burgers krijgen zo bijna letterlijk inzage in de parlementaire werking en de verkozenen van het volk zien als het ware hoe de burgers op hen toekijken. Dus geen beslissingen meer in duistere achterkamertjes maar openbare debatten die dan via televisie en het internet gevolgd kunnen worden door al wie interesse heeft. Transparantie wordt ook geëist van zowat alle burgers om aan te tonen dat ze ‘niets te verbergen hebben’ en daarom figuurlijk doorzichtig moeten zijn. Leve de transparantie dus. Maar tegen die trend in schreef de Nederlandse hoogleraar Bestuurskunde Paul Frissen het boek Het geheim van de laatste staat waarin hij kritiek geeft op de transparantie en pleit voor het fundamentele recht van de burger op geheimen als één van de waarborgen van zijn vrijheid.

Gewalt, Wut und Zorn sind ohnehin Schlüsselbegriffe in der Welt des Marc Jongen. «Wir pflegen kaum noch die thymotischen Tugenden, die einst als die männlichen bezeichnet wurden», doziert der Philosoph, weil «unsere konsumistische Gesellschaft erotozentrisch ausgerichtet» sei. Für die in klassischer griechischer Philosophie weniger bewanderten Leserinnen und Leser: Platon unterscheidet zwischen den drei «Seelenfakultäten» Eros (Begehren), Logos (Verstand) und Thymos (Lebenskraft, Mut, mit den Affekten Wut und Zorn). Jongen spricht gelegentlich auch von einer «thymotischen Unterversorgung» in Deutschland. Es fehle dem Land an Zorn und Wut, und deshalb mangle es unserer Kultur auch an Wehrhaftigkeit gegenüber anderen Kulturen und Ideologien.

Gewalt, Wut und Zorn sind ohnehin Schlüsselbegriffe in der Welt des Marc Jongen. «Wir pflegen kaum noch die thymotischen Tugenden, die einst als die männlichen bezeichnet wurden», doziert der Philosoph, weil «unsere konsumistische Gesellschaft erotozentrisch ausgerichtet» sei. Für die in klassischer griechischer Philosophie weniger bewanderten Leserinnen und Leser: Platon unterscheidet zwischen den drei «Seelenfakultäten» Eros (Begehren), Logos (Verstand) und Thymos (Lebenskraft, Mut, mit den Affekten Wut und Zorn). Jongen spricht gelegentlich auch von einer «thymotischen Unterversorgung» in Deutschland. Es fehle dem Land an Zorn und Wut, und deshalb mangle es unserer Kultur auch an Wehrhaftigkeit gegenüber anderen Kulturen und Ideologien.

Giono, c’est autre chose. Sa correspondance avec Gallimard, qui vient de paraître, nous montre un personnage d’une duplicité peu commune. Dès 1928, Gaston lui propose de devenir son éditeur exclusif dès qu’il sera libre de ses engagements avec Grasset. Grand écrivain mais sacré filou, Giono n’aura de cesse de jouer un double jeu, se flattant d’être « plus malin » que ses éditeurs. Rien à voir avec Céline, âpre au gain, mais qui se targuait d’être « loyal et carré ». Giono, lui, n’hésitait pas à signer en même temps un contrat avec Grasset et un autre avec Gallimard pour ses prochains ouvrages. Chacun des deux éditeurs ignorant naturellement l’existence du traité avec son concurrent. But de la manœuvre : toucher deux mensualités (!). La mèche sera vite éventée. Fureur de Bernard Grasset qui voulut porter plainte pour escroquerie et renvoyer l’auteur indélicat devant un tribunal correctionnel. L’idée de Giono était, en théorie, de réserver ses romans à Gallimard et ses essais à Grasset. L’affaire ira en s’apaisant mais Giono récidivera après la guerre en proposant un livre à La Table ronde, puis un autre encore aux éditions Plon. En termes mesurés, Gaston lui écrit : « Comprenez qu’il est légitime que je sois surpris désagréablement. » Et de lui rappeler, courtoisement mais fermement, ses engagements, ses promesses renouvelées et ses constantes confirmations du droit de préférence des éditions Gallimard. En retour, Giono se lamente : « Avec ce que je dois donner au percepteur, je suis réduit à la misère noire. » Et en profite naturellement pour négocier ses nouveaux contrats à la hausse. Ficelle, il conserve les droits des éditions de luxe et n’entend pas partager avec son éditeur les droits d’adaptation cinématographiques de ses œuvres. Tel était Giono qui, sur ce plan, ne le cédait en rien à Céline. On peut cependant préférer le style goguenard de celui-ci quand il s’adresse à Gaston : « Si j’étais comme vous multi-milliardaire (…), vous ne me verriez point si harcelant… diable ! que vous enverrais loin foutre ! ² ».

Giono, c’est autre chose. Sa correspondance avec Gallimard, qui vient de paraître, nous montre un personnage d’une duplicité peu commune. Dès 1928, Gaston lui propose de devenir son éditeur exclusif dès qu’il sera libre de ses engagements avec Grasset. Grand écrivain mais sacré filou, Giono n’aura de cesse de jouer un double jeu, se flattant d’être « plus malin » que ses éditeurs. Rien à voir avec Céline, âpre au gain, mais qui se targuait d’être « loyal et carré ». Giono, lui, n’hésitait pas à signer en même temps un contrat avec Grasset et un autre avec Gallimard pour ses prochains ouvrages. Chacun des deux éditeurs ignorant naturellement l’existence du traité avec son concurrent. But de la manœuvre : toucher deux mensualités (!). La mèche sera vite éventée. Fureur de Bernard Grasset qui voulut porter plainte pour escroquerie et renvoyer l’auteur indélicat devant un tribunal correctionnel. L’idée de Giono était, en théorie, de réserver ses romans à Gallimard et ses essais à Grasset. L’affaire ira en s’apaisant mais Giono récidivera après la guerre en proposant un livre à La Table ronde, puis un autre encore aux éditions Plon. En termes mesurés, Gaston lui écrit : « Comprenez qu’il est légitime que je sois surpris désagréablement. » Et de lui rappeler, courtoisement mais fermement, ses engagements, ses promesses renouvelées et ses constantes confirmations du droit de préférence des éditions Gallimard. En retour, Giono se lamente : « Avec ce que je dois donner au percepteur, je suis réduit à la misère noire. » Et en profite naturellement pour négocier ses nouveaux contrats à la hausse. Ficelle, il conserve les droits des éditions de luxe et n’entend pas partager avec son éditeur les droits d’adaptation cinématographiques de ses œuvres. Tel était Giono qui, sur ce plan, ne le cédait en rien à Céline. On peut cependant préférer le style goguenard de celui-ci quand il s’adresse à Gaston : « Si j’étais comme vous multi-milliardaire (…), vous ne me verriez point si harcelant… diable ! que vous enverrais loin foutre ! ² ».

Le préfixe dys de dystopie renvoie au grec dun qui est l’antithèse de la deuxième acception étymologique d’utopie (non pas u mais eu, “lieu du bien”). On fait remonter l’origine du mot “dystopie” tantôt au livre du philosophe tchèque

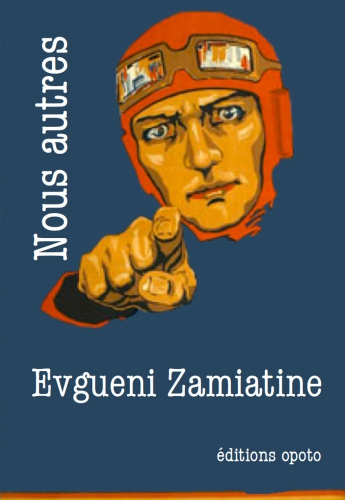

Le préfixe dys de dystopie renvoie au grec dun qui est l’antithèse de la deuxième acception étymologique d’utopie (non pas u mais eu, “lieu du bien”). On fait remonter l’origine du mot “dystopie” tantôt au livre du philosophe tchèque  C’est en 1920 avec la parution de Nous autres que la fiction dystopique naît véritablement. Cette œuvre phare de l’ingénieur russe Evguéni Ivanovitch Zamiatine donne ainsi ses “lettres de noblesses” au genre. Son ouvrage influença considérablement bon nombre de récits analogues tels que Le Meilleur des mondes d’Huxley et 1984 d’Orwell, publiés respectivement douze et vingt-huit ans plus tard.

C’est en 1920 avec la parution de Nous autres que la fiction dystopique naît véritablement. Cette œuvre phare de l’ingénieur russe Evguéni Ivanovitch Zamiatine donne ainsi ses “lettres de noblesses” au genre. Son ouvrage influença considérablement bon nombre de récits analogues tels que Le Meilleur des mondes d’Huxley et 1984 d’Orwell, publiés respectivement douze et vingt-huit ans plus tard. Ces œuvres voient donc dans l’utopie non pas une chance pour l’humanité, mais un risque de dégénérescence terriblement inhumaine qu’il faut empêcher à tout prix. Le but n’est pas de réaliser des utopies, mais au contraire d’empêcher qu’elles se réalisent. C’est l’avertissement du philosophe existentialiste

Ces œuvres voient donc dans l’utopie non pas une chance pour l’humanité, mais un risque de dégénérescence terriblement inhumaine qu’il faut empêcher à tout prix. Le but n’est pas de réaliser des utopies, mais au contraire d’empêcher qu’elles se réalisent. C’est l’avertissement du philosophe existentialiste

Net als Carl Schmitt (1888-1985) voert Chantal Mouffe de differentia specifica van het politieke terug op het onderscheid tussen vriend en vijand; oftewel tot de altijd aanwezige mogelijkheid van vijandelijkheid in intermenselijke relaties. Mouffe zegt niet dat alle sociale relaties noodzakelijk antagonistisch zijn, maar dat de mogelijkheid van conflict en vijandigheid in elke relatie op elk moment aanwezig is. Het politieke heeft altijd te maken met conflict en antagonisme, het gaat altijd gepaard met de formatie van een ‘wij’ versus een ‘zij’. In de discourstheorie van Laclau en Mouffe heet dit equivalentielogica: het opdelen van de sociale ruimte door betekenissen en identiteiten te comprimeren tot twee antagonistische polen.

Net als Carl Schmitt (1888-1985) voert Chantal Mouffe de differentia specifica van het politieke terug op het onderscheid tussen vriend en vijand; oftewel tot de altijd aanwezige mogelijkheid van vijandelijkheid in intermenselijke relaties. Mouffe zegt niet dat alle sociale relaties noodzakelijk antagonistisch zijn, maar dat de mogelijkheid van conflict en vijandigheid in elke relatie op elk moment aanwezig is. Het politieke heeft altijd te maken met conflict en antagonisme, het gaat altijd gepaard met de formatie van een ‘wij’ versus een ‘zij’. In de discourstheorie van Laclau en Mouffe heet dit equivalentielogica: het opdelen van de sociale ruimte door betekenissen en identiteiten te comprimeren tot twee antagonistische polen. Wat een radicale democratie à la Laclau en Mouffe onderscheidt van de moderne politieke projecten, is dat ze niet van een realiseerbare telos uitgaat, maar van het besef dat elk sociaal project onvolmaakt en conflictueel zal blijven. Het streven naar een volledig democratische maatschappij, waarin alle mensen volledig vrij zijn omdat ze volledig gelijk zijn, en vice versa, veronderstelt een volledige transparantie. Het veronderstelt een samenleving zonder spanningen en repressie, die dus alle conflicten onderdrukt. [11] Zo’n harmonieuze democratie zou een totalitaire nachtmerrie zijn. Bij Laclau en Mouffe wordt de mogelijkheid om het finale doel te realiseren verlaten, zelfs als louter regulatief idee. Er is trouwens geen reden om dat te betreuren. Integendeel, het is de garantie dat het democratisch-pluralistisch proces aan de gang blijft. Het is door de liberale rechten samen met volkssoevereiniteit te articuleren, dat we vermijden dat de democratie tiranniek wordt. Een ideale, vrije en gelijke democratische samenleving is er noodzakelijk een zonder pluralisme, want pluralisme veronderstelt dat de sociale orde en haar machtsrelaties kunnen worden gecontesteerd. Een samenleving zonder machtsrelaties (het einde van de politiek) is evenmin mogelijk, want het zijn precies de machtsrelaties die de sociale orde constitueren. Laclau en Mouffe vertrekken dus van een niet-reduceerbare, pluralistische sociale orde; en dit betekent dat de finale sociale orde nooit bereikt wordt. Niet alleen de individuen verkeren in de onmogelijkheid om hun identiteiten te finaliseren; ook de samenleving als zodanig is nooit af.

Wat een radicale democratie à la Laclau en Mouffe onderscheidt van de moderne politieke projecten, is dat ze niet van een realiseerbare telos uitgaat, maar van het besef dat elk sociaal project onvolmaakt en conflictueel zal blijven. Het streven naar een volledig democratische maatschappij, waarin alle mensen volledig vrij zijn omdat ze volledig gelijk zijn, en vice versa, veronderstelt een volledige transparantie. Het veronderstelt een samenleving zonder spanningen en repressie, die dus alle conflicten onderdrukt. [11] Zo’n harmonieuze democratie zou een totalitaire nachtmerrie zijn. Bij Laclau en Mouffe wordt de mogelijkheid om het finale doel te realiseren verlaten, zelfs als louter regulatief idee. Er is trouwens geen reden om dat te betreuren. Integendeel, het is de garantie dat het democratisch-pluralistisch proces aan de gang blijft. Het is door de liberale rechten samen met volkssoevereiniteit te articuleren, dat we vermijden dat de democratie tiranniek wordt. Een ideale, vrije en gelijke democratische samenleving is er noodzakelijk een zonder pluralisme, want pluralisme veronderstelt dat de sociale orde en haar machtsrelaties kunnen worden gecontesteerd. Een samenleving zonder machtsrelaties (het einde van de politiek) is evenmin mogelijk, want het zijn precies de machtsrelaties die de sociale orde constitueren. Laclau en Mouffe vertrekken dus van een niet-reduceerbare, pluralistische sociale orde; en dit betekent dat de finale sociale orde nooit bereikt wordt. Niet alleen de individuen verkeren in de onmogelijkheid om hun identiteiten te finaliseren; ook de samenleving als zodanig is nooit af. De ideologische tegenstellingen tussen de gevestigde partijen is in de loop van het laatste decennium alsmaar kleiner geworden, waardoor het steeds moeilijker is om partijen en politici in hun optreden en standpunten te onderscheiden. Ideologische beginselen boeten aan belang in, terwijl politiek pragmatisme en consensuspolitiek op de voorgrond treden. In de consensuspolitiek van het centrum, zegt ook de Sloveense filosoof Slavoj Zizek, moet elke fundamentele belangentegenstelling plaats ruimen voor een vrijmoedig geloof in een politiek zonder ware tegenstanders, en zonder enige subversiviteit. [12] Eens beyond left and right lossen sociale tegenstellingen vanzelf op en bieden er zich politieke oplossingen aan die kennelijk voor iedereen goed zijn. Bij gebrek aan een reële politieke strijd, onderscheiden politieke partijen zich enkel nog door culturele attitudes. De politieke strijd wordt herleid tot een belangencompetitie op neutraal terrein, met als enige doel het bereiken van compromissen en het aggregeren van voorkeuren. Om fundamentele belangenconflicten te omzeilen, weigert men om duidelijke politieke grenzen te trekken. Daarmee wordt de integratieve rol van conflict in de moderne democratie genegeerd. [13]

De ideologische tegenstellingen tussen de gevestigde partijen is in de loop van het laatste decennium alsmaar kleiner geworden, waardoor het steeds moeilijker is om partijen en politici in hun optreden en standpunten te onderscheiden. Ideologische beginselen boeten aan belang in, terwijl politiek pragmatisme en consensuspolitiek op de voorgrond treden. In de consensuspolitiek van het centrum, zegt ook de Sloveense filosoof Slavoj Zizek, moet elke fundamentele belangentegenstelling plaats ruimen voor een vrijmoedig geloof in een politiek zonder ware tegenstanders, en zonder enige subversiviteit. [12] Eens beyond left and right lossen sociale tegenstellingen vanzelf op en bieden er zich politieke oplossingen aan die kennelijk voor iedereen goed zijn. Bij gebrek aan een reële politieke strijd, onderscheiden politieke partijen zich enkel nog door culturele attitudes. De politieke strijd wordt herleid tot een belangencompetitie op neutraal terrein, met als enige doel het bereiken van compromissen en het aggregeren van voorkeuren. Om fundamentele belangenconflicten te omzeilen, weigert men om duidelijke politieke grenzen te trekken. Daarmee wordt de integratieve rol van conflict in de moderne democratie genegeerd. [13] Dienen we de kritiek van Chantal Mouffe op te vatten als een ultieme oproep om het cordon sanitaire in Vlaanderen dan toch maar op te doeken? Dat valt te betwijfelen. Waar het Mouffe om te doen is, is laten zien wat het ons heeft opgeleverd, om daaruit conclusies te trekken. Het probleem is overigens niet dat mensen uit zijn op conflict omwille van het conflict. Het probleem is dat, door het gebrek aan een sociale horizon, bepaalde sentimenten geen uitdrukking vinden binnen het democratisch spectrum. Deze sentimenten moeten democratisch gemobiliseerd worden; en daarvoor moeten de democratische partijen een sociale horizon projecteren die mensen uitzicht biedt op een andere en betere toekomst.

Dienen we de kritiek van Chantal Mouffe op te vatten als een ultieme oproep om het cordon sanitaire in Vlaanderen dan toch maar op te doeken? Dat valt te betwijfelen. Waar het Mouffe om te doen is, is laten zien wat het ons heeft opgeleverd, om daaruit conclusies te trekken. Het probleem is overigens niet dat mensen uit zijn op conflict omwille van het conflict. Het probleem is dat, door het gebrek aan een sociale horizon, bepaalde sentimenten geen uitdrukking vinden binnen het democratisch spectrum. Deze sentimenten moeten democratisch gemobiliseerd worden; en daarvoor moeten de democratische partijen een sociale horizon projecteren die mensen uitzicht biedt op een andere en betere toekomst.