Richard's post, "Obama's Ennabling Act," raises some interesting questions regarding the significance of the recently passed National Defense Authorization Act, and its probable impact, that I believe merit further discussion. The editorial issued on December 17 by the editors of Taki’s Magazine, “The Government v. Everyone,” represents fairly well the shared consensus of critics of the NDAA whose ranks include conservative constitutionalists and left-wing civil libertarians alike. While I share the opposition to the Act voiced by these critics, I also believe that Richard is correct to point out the questionable presumptions regarding legal and constitutional theory and alarmist rhetoric that have dominated the critics’ arguments.

Wholesale abrogation of core provisions of the U.S. Constitution is hardly rare in American history. The literature of leftist or libertarian historians of American politics is filled with references to the Alien and Sedition Act, Lincoln’s assumption of dictatorial powers during the Civil War, the repression of the labor movement during WWI, the internment of the Japanese during WW2 and so forth. Mainstream liberal critics of these aspects of American history will lament the manner by which America supposedly strays so frequently from her high-minded ideals, whereas more radical leftist critics will insist such episodes illustrate what a rotten society America always was right from the beginning.

Meanwhile, conservatives will lament how the noble, almost god-like efforts of the revered “Founding Fathers” have been perverted and destroyed by subsequent generations of evil or misguided liberals, socialists, atheists, or whomever, thereby plunging the nation into the present dark era of big government and moral decadence. These systems of political mythology not withstanding, a more realist-driven analysis of the history of the actual practice of American statecraft might conclude that such instances of the state stepping outside of its own proclaimed ideals or breaking its own rules transpire because, well, that’s what states do.

Carl Schmitt considered the essence of politics to be the existence of organized collectives with the potential to engage in lethal conflict with one another. Max Weber defined the state as an entity claiming a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence. Schmitt’s dictum, “Sovereign is he who decides on the state of exception,” indicates there must be some ultimate rule-making authority that decides what constitutes “legitimacy” and what does not, and that this sovereign entity is consequently not bound by its own rules. This principle is descriptive rather than prescriptive or normative in nature. Schmitt’s conception of the political is simply an analysis of “how things work” as opposed to “what ought to be.”

Like all other political collectives, the United States possesses a body of political mythology whose function is to convey legitimacy upon its own state. For Americans, this mythology takes on the form of what Robert Bellah identified as the “civil religion.” The tenets of this civil religion grant Americans a unique and exceptional place in history as the Promethean purveyors of “freedom,” “democracy,” “equality,” “opportunity,” or some other supposedly noble ideal. According to this mythology, America takes on the role of a providential nation that is in some way particularly favored by either a vague, deist-like divine force (Jefferson’s “nature’s god”) in the mainstream politico-religious culture, or the biblical god in the case of the evangelicals, or the progressive forces of history for left-wing secularists. The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution are the sacred writings of the American civil religion. It is no coincidence that constitutional fundamentalists and religious fundamentalists are often the same people. Prominent “founding fathers” such as Washington or Madison assume the role of prophets or patriarchs akin to Moses and Abraham.

In American political and legal culture, this civil religion and body of political mythology becomes intertwined with the liberal myth of the “rule of law.” According to this conception, “law” takes on an almost mystical quality and the Constitution becomes a kind of magical artifact (like the genie’s lantern) whose invocation will ostensibly ward off tyrants. This legal mythology is often expressed through slogans such as “We should be a nation of laws and not men” (as though laws are somehow codified by forces or entities other than mere mortal humans) and public officials caught acting outside strict adherence to legal boundaries are sometimes vilified for violation of “the rule of law.” (I recall comical pieties of this type being expressed during the Iran-Contra scandal of the late 1980s.) Ultimately, of course, there is no such thing as “the rule of law.” There is only the rule of the “sovereign.” The law is always subordinate to the sovereign rather than vice versa. Schmitt’s conception of the political indicates that the world is comprised first and foremost of brawling collectives struggling on behalf of each of their existential prerogatives. The practice of politics amounts to street-gang warfare writ large where the overriding principle becomes “protect one’s turf!” rather than “rule of law.”

As an aside, I am sometimes asked how my general adherence to Schmittian political theory can be reconciled with my anarchist beliefs. However, it was my own anarchism that initially attracted me to the thought of Schmitt. His recognition of the essence of the political as organized collectives with the potential to engage in lethal conflict and his understanding of sovereignty as exemption from the rule-making authority of the state have the ironic effect of stripping away and destroying the systems of mythology on which states are built. Schmitt’s analysis of the nature of the state is so penetrating that it gives the game away. Politics is simply about maintaining power. Period.

Another irony is that Schmitt helped to clarify my anarchist beliefs considerably. I adhere to the dictionary definition of anarchism as the goal of replacing the state with a confederation or agglomeration of voluntary communities (while recognizing a certain degree of subjectivity to the question of what is “voluntary” and what is not). Theoretically, anarchist communities could certainly reflect the values of ideological anarchists like Kropotkin, Rothbard, or Dorothy Day. But such communities could also be organized on the model of South Africa’s Orania, or traditionalist communities like the Hasidim or Amish, or fringe cultural elements like UFO true-believers. Paradoxically, such communities could otherwise reflect the “normal” values of Middle America (minus the state).

The concept of fourth generation warfare provides a key insight as to how political anarchism can be reconciled with the political theory of Carl Schmitt. According to fourth generation theory as it has been outlined by Martin Van Creveld and William S. Lind, the state is in the process of receding as the loyalties of populations are being transferred to other entities such as religions, tribes, ideological movements, gangs, cults, paramilitaries, or whatever. Scenarios are emerging with increasing frequency where such non-state actors engage in warfare with states or in the place of states. Lebanon’s Hezbollah, which has essentially replaced the Lebanese state as both the defender of the nation and as the provider of necessary services on which the broader population depends, is a standard model of a fourth generation entity. In other words, Hezbollah has replaced the state as the sovereign entity in Lebanese society.

Another example is Columbia’s FARC, which has likewise dislodged the Colombian state as the sovereign in FARC-controlled territorial regions. The implication of this for political anarchism is that for the anarchist goal of autonomous, voluntary communities to succeed, a non-state entity (or collection of entities) must emerge that is capable of protecting the communities from conquest or subversion and possesses the will to do so. In other words, for anarchism to work there must be in place the equivalent of an anarchist version of Hezbollah that replaces the state as the sovereign in the wider society, probably in the form of a decentralized militia confederation similar to that organized by the Anarchists of Catalonia during the Spanish Civil War…in case anyone was wondering.

The Future of Repression

Dealing with more immediate questions, the passage of the National Defense Authorization Act raises the issue of to what level repression carried out by the American state in the future will be taken, and of what particular form this repression will assume. I agree with Richard that it is improbable that NDAA represents any significant change of direction or dramatic acceleration in these areas. Therefore, it is highly unlikely that American political dissidents (the readers of AlternativeRight.Com, for instance) will be subject to mass arrests and indefinite detention without trial. Such tactics are likely to be reserved for individuals, primarily foreigners, genuinely involved or believed to be involved in the planning of acts of actual terrorism against American targets. There is at present very little of that within the context of domestic American society.

However, the unwarranted nature of Alex Jones-style alarmism does not mean there is no danger on the horizon. What is needed is a healthy medium between panic and complacency. Richard has argued that our present systems of soft totalitarianism that we find in the contemporary Western world may well give way to hard totalitarianism as Cultural Marxism/Totalitarian Humanism continues to tighten its grip. While this is a concern that I share and a prophecy that I regrettably think has a considerable chance of fulfillment, the question arises of what form “hard” totalitarianism might take in the future of the West.

It is unlikely we will ever develop states in the West that are organized on the classical totalitarian model complete with over the top pageantry and heads of states with strange uniforms and facial hair, given the way in which these are inimical to the universalist ideology, globalist ambitions, commercial interests, and aesthetic values of Western elites. Rather, I suspect the future of Western repression will take on either one of two forms (or perhaps a combination of both).

One of these is a model where repression rarely involves long term imprisonment or state-sponsored lethal action against dissidents. Instead, such repression might take on the form of persistent and arbitrary harassment, or the ongoing escalation of the use of professional and economic sanctions, targeting the families and associates of dissidents, or the petty criminalization of those who speak or act in defiance of establishment ideology. Richard has discussed the recent events involving Emma West and David Duke, and well as his own treatment at the hands of the Canadian authorities, and I suspect it is state action of this type that will largely define Western repression in the foreseeable future.

The state may not murder you or put you in prison for decades without trial, but you may lose your job, have your professional licensees revoked or the social service authorities threaten to remove your children from your home, or be subject to significant but brief harassment by legal authorities. You man find yourself brought up on minor criminal charges (akin to those that might be levied against a shoplifter or a pot smoker) if you utter the wrong words. Likewise, the state will increasingly look the other way as the use of extra-legal violence by leftist and other pro-system thugs is employed against dissenters. Indeed, much of what I have outlined here is already taking place and it can be expected that such incidents will become much more frequent and severe in the years and decades ahead. What I have outlined in this paragraph largely defines the practice of political repression as it currently exists in the West, particularly outside the United States, where traditions upholding free speech do not run quite as deeply.

However, this by no means indicates that Americans are off the hook. An even greater issue of concern, particularly for the United States, involves the convergence of four factors within contemporary American society and statecraft. These are the decline of the American empire in spite of the continuation of America’s massive military-industrial complex, mass immigration and radical demographic transformation, rapid economic deterioration and the disappearance of the conventional American middle class, and the growth of the general apparatus of state repression over the last four decades (the prison-industrial complex frequently criticized by the Left, for instance).

The combination of mass Third World immigration and ongoing economic decline, if continued uninterrupted, will have the effect of replicating the traditional Third World model class system in the U.S. (and perhaps much of the West over time). A class system organized on the basis of an opulent few at the top and impoverished many among the masses (the Brasillian model, for instance) will likely be accompanied by escalating social unrest and political instability. Such trends will be ever more greatly exacerbated by growing social, cultural, and ethnic conflict brought about by demographic change.

The American state has at its disposal an enormous military industrial complex that, frankly, wants to remain in business even as foreign military adventures continue to become less politically and economically viable. Likewise, the ongoing domestic wars waged by the American state against drugs, crime, gangs, guns, et. al. have generated a rather large “police industrial complex” with American borders. Libertarian writers such as William Norman Grigg have diligently documented the ongoing process of the militarization of American law enforcement and the continued blurring of distinctions between the rules of engagement involving soldiers on the battlefield on one hand and policemen dealing with civilians on the other. The literature of libertarian critics is filled with horror stories of, for instance, small town mayors having their household pets blown away by SWAT team members during the course of bungled drug raids.

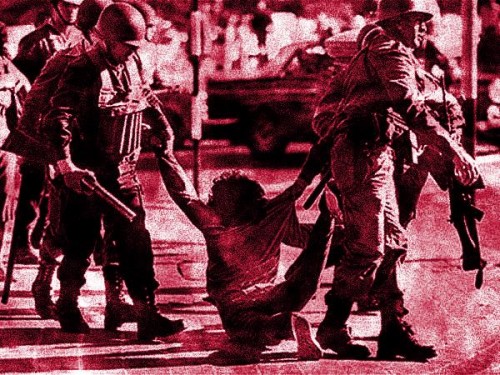

The point is that as economic and social unrest, along with increasingly intense demographic conflict, continues to arise as it likely will in the foreseeable American future, the state will have at its disposal a significant apparatus for the carrying out of genuinely brutal repression of the kind normally associated with Latin American or Middle Eastern countries. Recall, for example, the “disappeared” of Latin America during the 1970s and 1980s. It is not improbable that we dissidents in the totalitarian humanist states of the postmodern West will face a dangerous brush with such circumstances at some point in the future.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Il caso Chomsky e la democrazia in Israele

Il caso Chomsky e la democrazia in Israele Die Wirtschaftskrise und die sie begleitenden wachsenden Unruhen bieten der Brüsseler EU-Regierung eine willkommene Gelegenheit, um in aller Stille die Einsatzfähigkeit einer geheimen EU-Truppe zu testen, die für die Niederschlagung von Aufständen in der EU aufgestellt wurde. Diese geheime EU-Truppe heißt EUROGENDFOR, hat ihren Sitz in Norditalien und ist nun abmarschbereit nach Griechenland für den ersten großen Einsatz gegen die Bevölkerung eines EU-Landes.

Die Wirtschaftskrise und die sie begleitenden wachsenden Unruhen bieten der Brüsseler EU-Regierung eine willkommene Gelegenheit, um in aller Stille die Einsatzfähigkeit einer geheimen EU-Truppe zu testen, die für die Niederschlagung von Aufständen in der EU aufgestellt wurde. Diese geheime EU-Truppe heißt EUROGENDFOR, hat ihren Sitz in Norditalien und ist nun abmarschbereit nach Griechenland für den ersten großen Einsatz gegen die Bevölkerung eines EU-Landes.