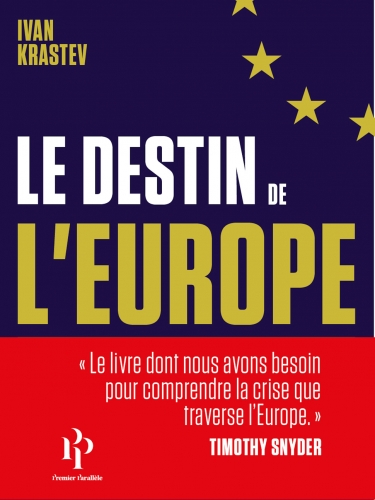

Politologue d’origine bulgare, Ivan Krastev est un des fondateurs du Conseil européen des relations étrangères et le directeur de l’édition bulgare de Foreign Policy, la revue étatsunienne proche des cénacles interventionnistes mondialistes. Il appartient pleinement à cette caste cosmopolite. Les crises simultanées ou quasi-consécutives de l’euro, des migrants, de l’Ukraine, du Brexit, de la Catalogne, etc., qui ébranlent la construction européenne lui donnent une sensation de déjà vu. L’étudiant qu’il était en Bulgarie en 1989 – 1990 a vécu l’effondrement rapide du système soviétique. Il craint maintenant de connaître un nouvel effondrement, celui des structures eurocratiques. Son essai s’ouvre d’ailleurs sur les derniers instants de l’Empire austro-hongrois. « Vivons-nous aujourd’hui, en Europe, un “ moment de désintégration ” similaire (p. 9) » à la chute des Habsbourg ?

Le destin de l’Europe a été écrit au lendemain du Brexit et de l’élection de Donald Trump. Krastev se félicite bien sûr des échecs répétés du « populisme » en Autriche, aux Pays-Bas et en France. Il ne pouvait néanmoins pas prévoir que cet arrêt ne serait que momentané. Depuis la parution de son ouvrage en France, l’Autriche est gouvernée par une coalition entre les conservateurs et le FPÖ, la Hongrie a triomphalement réélu Viktor Orban et une entente entre le Mouvement Cinq Étoiles et la Ligue dirige désormais l’Italie. On peut imaginer que l’auteur développera ces derniers événements dans un prochain essai.

L’Europe, destination de Cocagne…

Peut-être y approfondira-t-il aussi son analyse de « géopolitique psychologique » qu’il émet au sujet des États-Unis ? « De nombreuses cartes électorales dessinées après la victoire de Trump aux dernières présidentielles américaines montrent très bien que, si les régions acquises à Trump correspondent à peu près à 85 % du territoire total des États-Unis, les régions acquises, elles, à Clinton représentent en gros 54 % de la population américaine. Si nous imaginons que ces régions constituent deux pays différents, nous notons immédiatement que le “ pays de Clinton ”, composé des régions côtières et d’îles urbaines, évoquent l’Angleterre du XIXe siècle; tandis que le “ pays de Trump ” ressemble quant à lui bien plus aux grandes étendues de l’Eurasie régentées par la Russie et l’Allemagne. Le combat politique qui a opposé Clinton et Trump fut un combat entre dimension maritime et dimension terrestre, entre des personnes pensant en termes d’espace et des personnes pensant en termes de lieux (pp. 49 – 50). » Subtile insinuation pour rapprocher Trump de la Russie de Vladimir Poutine…

Peut-être y approfondira-t-il aussi son analyse de « géopolitique psychologique » qu’il émet au sujet des États-Unis ? « De nombreuses cartes électorales dessinées après la victoire de Trump aux dernières présidentielles américaines montrent très bien que, si les régions acquises à Trump correspondent à peu près à 85 % du territoire total des États-Unis, les régions acquises, elles, à Clinton représentent en gros 54 % de la population américaine. Si nous imaginons que ces régions constituent deux pays différents, nous notons immédiatement que le “ pays de Clinton ”, composé des régions côtières et d’îles urbaines, évoquent l’Angleterre du XIXe siècle; tandis que le “ pays de Trump ” ressemble quant à lui bien plus aux grandes étendues de l’Eurasie régentées par la Russie et l’Allemagne. Le combat politique qui a opposé Clinton et Trump fut un combat entre dimension maritime et dimension terrestre, entre des personnes pensant en termes d’espace et des personnes pensant en termes de lieux (pp. 49 – 50). » Subtile insinuation pour rapprocher Trump de la Russie de Vladimir Poutine…

Pour Ivan Krastev, le destin de l’Europe ne concerne pas l’avenir de l’euro, le devenir des relations euro-atlantiques ou le sort de l’Ukraine et des minorités russophones, mais le traitement des immigrés clandestins. « Au XXIe siècle, la migration est la nouvelle révolution – non pas une révolution des masses comme au XXe siècle, mais une révolution menée contre leur gré par des individus et des familles chassés de chez eux (p. 24). » Il ne s’interroge jamais sur ses causes. Les immigrés quittent leur foyer parce qu’ils fuient l’impitoyable domination économique néo-coloniale de Wall Street, de Chicago et de la City, ainsi que les opérations déstabilisatrices menées par l’Occident au Sahel, en Libye, en Syrie et au Yémen.

Véritable submersion démographique, la présente immigration de peuplement engendre une aporie. « Afin d’assurer leur prospérité, les Européens ont besoin d’ouvrir leurs frontières; pourtant, une telle ouverture menace d’annihiler ce qui fait leur spécificité culturelle (p. 61). » Cette crainte réelle que minimise l’auteur suscite la confrontation entre « ceux du n’importe où » et « ceux du quelque part (p. 49) ». Les immigrés viennent en Europe attirés par les images désormais diffusées par tout type d’écran qui leur présentent des pays de Cocagne. « La globalisation a fait du monde un village, mais celui-ci vit sous une sorte de dictature : la dictature des comparaisons globales (p. 45). » Films, séries télévisées et réclame publicitaire influencent les futurs clandestins qui se prennent à rêver de vivre comme des Occidentaux tout en conservant leurs coutumes d’origine. Ce désir, purement matérialiste, hédoniste et eudémoniste, serait rarement politique. « Un simple franchissement de frontière – celle de l’Union européenne en l’occurrence – est ici plus attirant que toute utopie. Pour tant de damnés de la Terre d’aujourd’hui, l’idée de changement est synonyme de changement de pays, de départ, et non pas de changement de gouvernement (pp. 44 – 45). »

Les immigrés ne comprennent pas qu’en tentant leur chance en Europe, ils perturbent des modes de vie ancestraux déjà bien fragilisés. « Seule crise authentiquement paneuropéenne, [la crise des “ migrants ”] remet en cause le modèle politique, économique et social de l’Europe (p. 29) », de l’Union soi-disant européenne faudrait-il plutôt écrire. Cette remise en cause est en soi salutaire puisque « l’Union européenne est désormais prônée, du moins par bon nombre de ses partisans, comme le dernier espoir d’un continent devenu forteresse (p. 54) ». Longtemps, l’Union dite européenne s’est ouverte à tous les vents de la concurrence planétaire et a condamné Budapest pour son intransigeance à appliquer les Accords de Schengen. Or, la roue de l’Histoire tourne. Le Danemark, l’Autriche et l’Italie approuvent en partie l’argumentation du Groupe de Visegrad animé par la Hongrie et la Pologne afin de contenir la submersion migratoire. Délaissant la question « souverainiste » de l’euro pour l’enjeu « identitaire » des migrations extra-européennes, le nouveau gouvernement « anti-Système » italien comprend instinctivement qu’une autre Europe pourrait résoudre avec fermeté ce défi majeur à la condition toutefois qu’elle entérine enfin un « post-libéralisme ».

En effet, pour l’auteur, « les migrants sont ces acteurs de l’Histoire qui décideront du sort du libéralisme européen (p. 33) ». Soucieux de l’avenir de cette pensée obsolète, il se préoccupe de la floraison rapide des régimes illibéraux en Europe centrale, orientale et maintenant occidentale. Ainsi nomme-t-il le « paradoxe centre-européen (p. 97) » qui complète un autre paradoxe, « ouest-européen (p. 111) » celui-là, à savoir des générations connectées et mondialisées, les enfants du programme Erasmus, qui se détournent dorénavant du projet européen « bruxellois » et qui adhèrent au « populisme »…

Contre l’internationalisme financier

Ivan Krastev oublie dans sa démonstration que la Pologne accueille déjà des miliers de réfugiés ukrainiens sans que cette présence massive n’entraîne d’insurmontables problèmes de cohabitation. La proximité anthropologique, culturelle et historique joue ici à plein, ce que Bruxelles persiste à ne pas vouloir comprendre. Résultat, « les nouvelles majorités populistes perçoivent les élections comme une occasion non pas de choisir entre différentes options politiques mais de se révolter contre des minorités privilégiées – dans le cas de l’Europe, de se révolter contre ses élites mais aussi contre un “ autre ” collectif clé : les migrants (p. 100). » il ajoute toutefois que « les visages de Janus de la globalisation sont ceux du touriste et du réfugié. Le touriste, protagoniste de la globalisation, est apprécié et accueilli à bras ouverts. Il est l’étranger bienveillant. […] Le réfugié […] incarne la nature menaçante de la globalisation. […] Il est parmi nous mais sans être des nôtres (pp. 28 – 29) ». En réalité, le tourisme lui-même est une nuisance, un fléau pour les sociétés qui ne tablent que sur cette forme unique de développement.

Approchent donc les temps des affrontements entre colons et autochtones en terres d’Europe. « Des outsiders arrivent de toutes parts, les natifs, eux, n’ayant aucune possibilité de prendre la tangente. En ce sens, les électeurs des formations droitières perçoivent leur destin comme étant bien plus tragique que celui des pieds-noirs français, parce qu’ils n’ont, eux, pas d’endroit où retourner (p. 41). » C’est la raison pour laquelle la crise migratoire peut soit précipiter la décadence de l’Europe, soit faciliter la fondation d’une véritable renaissance civilisationnelle identitaire. Alors que « l’Europe est intégrée comme elle ne l’a jamais été auparavant (p. 10) », la construction européenne continue à se dépolitiser, à neutraliser tout élément de puissance, à demeurer une entité purement technique, administrative et fonctionnelle. « Il nous faut reconnaître que le projet européen actuel est intellectuellement enraciné dans l’idée de “ fin de l’Histoire ” (p. 31). » Pis, « l’Union européenne a toujours été une idée en quête de réalité (p. 13) ».

La brutalité de la crise migratoire pourrait redonner à un projet continental refondé les moyens d’aboutir sur de nouvelles assises novatrices hors du champ électoral politicien bien décati. « La ligne de partage gauche – droite, qui avait été sévèrement tracé et qui avait structuré la politique européenne depuis la Révolution française, s’en voit progressivement brouillée (p. 109). » Mieux, « le clivage gauche – droite se voit […] remplacé par un conflit opposant internationalistes et nativistes (p. 99) ». Les « nativistes » peuvent et doivent construire une alter Europe puissante et viable, une Europe d’après. « Parler d’une Europe d’après signifie que le Vieux Continent a à la fois perdu la position centrale qui était la sienne dans la politique internationale, à l’échelle du globe, et la confiance des Européens eux-mêmes – leur confiance en la capacité de ses choix politiques à façonner l’avenir du monde. Parler d’une Europe d’après, c’est dire que le projet européen a perdu de son attrait téléologique et que l’idée d’« États-Unis d’Europe » est bien moins source d’inspiration qu’auparavant – jamais sans doute le fut-elle aussi peu au cours de ces cinquante dernières années. Parler d’une Europe d’après, c’est signifier que l’Europe souffre d’une crise d’identité, que son héritage chrétien ainsi que le legs des Lumières ne sont plus pour elle des piliers de soutènement sûrs (p. 18). » Excellente nouvelle ! L’Europe n’est plus le phare du monde ! « Le postmodernisme de l’Europe, son postnationalisme et sa culture laïque la distinguent du reste du monde et n’en font pas nécessairement le modèle d’une éventuelle évolution future de ce monde (p. 17). » L’Europe de demain sera peut-être une Europe archaïque enfin délestée des fétides droits de l’homme.

Illibéralisme pro-européen ?

Ivan Krastev avance en outre un fait méconnu. « Alors que l’Union européenne est fondée à la fois sur l’idée française de nation (pour laquelle l’appartenance nationale est synonyme de loyauté aux institutions de la République) et sur la conception allemande de l’État (de puissants Länder et un centre fédéral relativement faible), les États d’Europe centrale, eux, ont été construits à l’inverse : ils combinent une admiration très française pour un État centralisé et tout-puissant avec une conception de la citoyenneté comme ascendance commune et culture partagée (pp. 68 – 69). » D’où le succès de l’illibéralisme à Bratislava, à Varsovie et à Budapest. L’illibéralisme serait au fond la fusion de Colbert et de Bismarck. L’auteur n’a pas tort, mais il se focalise trop sur les immigrés, quitte à mésestimer l’impact de l’euro dans la vie quotidienne et l’égoïsme sournois allemand. Contrairement à ce que pensent les nationaux-républicains et autres souverainistes nationaux de France et de Navarre, l’Allemagne n’est nullement européiste. Sous tutelle étatsunienne depuis 73 ans, elle refuse toute véritable unité européenne susceptible de s’affranchir du giron atlantiste. À diverses reprises, le Tribunal constitutionnel de Karlsruhe a réaffirmé une pseudo-souveraineté par rapport aux mécanismes institutionnels européens. Ayant renoncé à l’orée des années 2000 au modèle rhénan, les gouvernements d’outre-Rhin ont perverti l’ordo-libéralisme et imposé d’abord aux Allemands, puis aux peuples du « Club Med » ou aux PIGS (acronyme anglais signifiant « Cochons » pour désigner le Portugal, l’Italie, la Grèce et l’Espagne) des cures toujours plus sévères d’austérité si bien que témoins de cet asservissement financier qui bafoue le droit des peuples à disposer d’eux-mêmes, Hongrois, Slovaques, Tchèques, Polonais ont commencé à se révolter « contre les principes et les institutions du libéralisme constitutionnel, qui vont les piliers de soutènement même de l’Union européenne (p. 110) ».

Cependant, « si la désintégration devait se produire, ce ne serait pas en raison d’une désertion de la périphérie mais d’une révolte du centre (p. 19) ». Il n’est pas impossible que l’Allemagne se retire finalement de la Zone euro en compagnie de la Finlande, des États baltes, de l’Autriche, des Pays-Bas et de la Flandre (ou de la Belgique si elle n’explose pas sous la pression conjuguée des revendications nationales flamandes et communautaristes musulmanes) pour former une Zone euromark. Les membres restants de l’Eurolande constitueraient alors autour de la France une Zone eurofranc (hypothèse de l’économiste Christian Saint-Étienne dans La fin de l’euro en 2009). La guerre commerciale lancée par Donald Trump risque d’affecter en priorité l’industrie allemande. Berlin pourrait dès lors dévisser en terme de compétitivité économique et envisager un « Germanexit » qui avantagerait les collusions transatlantiques et empêcherait la constitution de tout axe grand-continental Madrid – Rome – Paris – Berlin – Moscou – Téhéran – Delhi – Pékin. Cet axe se concrétise par les nouvelles « Routes de la soie » à travers les premières liaisons ferroviaires sino-européennes. Si cette prévision se réalisait, la finalité de la construction européenne s’en trouverait totalement bouleversée.

Extorsions bancaires

La défiance des peuples d’Europe à l’égard des instances supranationales ne cesse de croître. En effet, « au lieu de redistribuer les produits de l’imposition, des classes fortunées vers les classes pauvres, les gouvernements européens maintiennent désormais leur santé financière précaire en empruntant au nom des générations futures sous la forme du financement par le crédit. Par conséquent, les populations ont perdu le pouvoir démocratique de réguler le marché à travers leur participation aux élections (p. 15) ». Ivan Krastev estime que « si l’Union devait s’effondrer, la logique de sa fragmentation serait celle d’un retrait massif de dépôts bancaires et non celle d’une révolution (p. 19) », d’où plusieurs mesures adoptées depuis une décennie par la Commission afin de déposséder légalement les détenteurs de compte bancaire à l’exemple de Chypre et de la Grèce. Une directive européenne prise en 2013 et effective depuis le 1er janvier 2016 stipule que les dépôts bancaires des particuliers et des entreprises s’élevant à plus de 100 000 € pourraient être mis autoritairement à contribution afin de renflouer les banques en faillite. Ce montant pourrait bien évidemment baisser pour mieux spolier l’ensemble de la population dont les plus fragiles. La saisie prochaine des biens immobiliers (et uniquement immobiliers), en particulier des retraités, des chômeurs et des travailleurs précaires, est programmée par les mafias bancaires liées à l’Oligarchie mondiale. L’emploi de plus en plus fréquent de la monnaie électronique en Occident, mais aussi en Inde et en Corée du Sud, prépare cette future expropriation insidieuse pour le seul profit des banksters et des marchés. Déjà, en novembre 2011, « la chute de Berlusconi […] symbolisa plutôt le triomphe sans équivoque du pouvoir des marchés financiers (p. 93) ». Dernièrement, le 29 mai 2018, le commissaire « européen » au Budget, l’Allemand Günther Oettinger, déclarait au sujet de l’entente gouvernementale conclue entre le Mouvement Cinq Étoiles et la Ligue que « les marchés vont apprendre aux Italiens à bien voter ». Il a ensuite démenti ses propos tout en maintenant le fond de sa pensée.

La défiance des peuples d’Europe à l’égard des instances supranationales ne cesse de croître. En effet, « au lieu de redistribuer les produits de l’imposition, des classes fortunées vers les classes pauvres, les gouvernements européens maintiennent désormais leur santé financière précaire en empruntant au nom des générations futures sous la forme du financement par le crédit. Par conséquent, les populations ont perdu le pouvoir démocratique de réguler le marché à travers leur participation aux élections (p. 15) ». Ivan Krastev estime que « si l’Union devait s’effondrer, la logique de sa fragmentation serait celle d’un retrait massif de dépôts bancaires et non celle d’une révolution (p. 19) », d’où plusieurs mesures adoptées depuis une décennie par la Commission afin de déposséder légalement les détenteurs de compte bancaire à l’exemple de Chypre et de la Grèce. Une directive européenne prise en 2013 et effective depuis le 1er janvier 2016 stipule que les dépôts bancaires des particuliers et des entreprises s’élevant à plus de 100 000 € pourraient être mis autoritairement à contribution afin de renflouer les banques en faillite. Ce montant pourrait bien évidemment baisser pour mieux spolier l’ensemble de la population dont les plus fragiles. La saisie prochaine des biens immobiliers (et uniquement immobiliers), en particulier des retraités, des chômeurs et des travailleurs précaires, est programmée par les mafias bancaires liées à l’Oligarchie mondiale. L’emploi de plus en plus fréquent de la monnaie électronique en Occident, mais aussi en Inde et en Corée du Sud, prépare cette future expropriation insidieuse pour le seul profit des banksters et des marchés. Déjà, en novembre 2011, « la chute de Berlusconi […] symbolisa plutôt le triomphe sans équivoque du pouvoir des marchés financiers (p. 93) ». Dernièrement, le 29 mai 2018, le commissaire « européen » au Budget, l’Allemand Günther Oettinger, déclarait au sujet de l’entente gouvernementale conclue entre le Mouvement Cinq Étoiles et la Ligue que « les marchés vont apprendre aux Italiens à bien voter ». Il a ensuite démenti ses propos tout en maintenant le fond de sa pensée.

Les « marchés » ne sont pas éthérés. Ce sont des algorithmes fort complexes et des individus qui recherchent avant tout leur seul intérêt personnel. « En Europe, note Ivan Krastev, l’élite méritocratique est une élite mercenaire dont les membres ne se comportent pas différemment de ces stars de football que s’arrachent les plus grands clubs à coups de chéquiers. […] Les banquiers néerlandais à la carrière fulgurante partent à Londres. Les hauts fonctionnaires allemands de talent rejoignent Bruxelles (p. 120). » Capables de faire défection dès le premier contretemps survenu, « les élites méritocratiques de notre temps, de cette époque de globalisation et d’intégration européenne, sont des élites de la “ no loyalty ”, pour laquelle l’idée d’allégeance nationale n’a pas de sens (p. 122) ». Serait-ce le rôle d’autres élites pas encore advenues d’orienter le projet européen vers une autre direction : la survie ethnique des peuples albo-européens ? Face au tsunamimigratoire, « les Européens pourraient bien sûr opter pour l’autre possibilité et fermer leurs frontières; mais alors il leur faudrait se préparer à un déclin brutal de leur niveau de vie général ainsi qu’à un futur où tout le monde aurait besoin de travailler jusqu’à ce que le corps ne puisse plus suivre (p. 61) ». Cette hypothèse ne se vérifierait que si les Européens commettaient l’erreur de garder leur modèle moderne, libéral, individualiste et bourgeois dépassé. Leur révolution est d’abord spirituelle et morale. Ils doivent par conséquent écarter certains arguments immigrationnistes fallacieux. Les immigrés représenteraient une nouvelle main-d’œuvre bon marché suppléant le vieillissement de l’Europe. Or, le progrès technique annule cette justification. « La peur d’une invasion barbare cœxiste […] avec une autre peur, prévient encore Krastev : celle de voir le lieu de travail bouleversé par les transformations liées à la robotique. Dans la dystopie technologique que nous voyons naître, il n’y aura tout simplement plus de travail pour les êtres humains (p. 60). » Dans une trentaine d’années, 43 % des postes de travail actuels seraient automatisés, robotisés et informatisés. Le travail ne sera plus un droit ou un devoir, mais un simple privilège. Que faire des masses inemployées ?

Dans ces conditions, les Européens peuvent fort bien prendre la voie de la décroissance, de la frugalité et de la pauvreté volontaire couplée à une implacable préférence européenne. L’Europe cesserait dès lors d’être attractive. Si l’Europe veut vraiment conserver un destin, elle devra accepter un avenir spartiate.

Georges Feltin-Tracol

• Ivan Krastev, Le destin de l’Europe. Une sensation de déjà vu, Éditions Premier Parallèle, 2017, 155 p., 16 €.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

One might fairly assert that Berdyaev did himself little good publicity-wise by cultivating a style of presentation which, while often resolving its thought-processes in a brilliant, aphoristic utterance, nevertheless takes its time, looks at phenomena from every aspect, analyzes every proposition to its last comma and period, and tends to assert its findings bluntly rather than to argue them politely in the proper syllogistic manner. In Berdyaev’s defense, a sensitive reader might justifiably interpret his leisurely examination of the modern agony as a deliberate and quite appropriate response to the upheavals that harried him from the time of the 1905 Revolution to the German occupation of France during World War II. If the Twentieth Century insisted on being precipitate and eruptive in everything, without regard to the lethal mayhem it wreaked, then, by God, Berdyaev, regarding his agenda, would take his sweet time. Not for him the constant mobilized agitation, the sloganeering hysteria, the goose-stepping and dive-bombing spasms of modernity in full self-apocalypse. That is another characteristic of Berdyaev – he is all at once leisurely in style and apocalyptic in content. Berdyaev was quite as apocalyptic in his expository prose as his idol Fyodor Dostoevsky was in his ethical narrative, and being a voice of revelation he expressed himself, again like Dostoevsky, in profoundly religious and indelibly Christian terms. Berdyaev follows Dostoevsky and anticipates Alexander Solzhenitsyn in his conviction that no society can murder God, as Western secular society has gleefully done, and then go its insouciant way, without consequence.

One might fairly assert that Berdyaev did himself little good publicity-wise by cultivating a style of presentation which, while often resolving its thought-processes in a brilliant, aphoristic utterance, nevertheless takes its time, looks at phenomena from every aspect, analyzes every proposition to its last comma and period, and tends to assert its findings bluntly rather than to argue them politely in the proper syllogistic manner. In Berdyaev’s defense, a sensitive reader might justifiably interpret his leisurely examination of the modern agony as a deliberate and quite appropriate response to the upheavals that harried him from the time of the 1905 Revolution to the German occupation of France during World War II. If the Twentieth Century insisted on being precipitate and eruptive in everything, without regard to the lethal mayhem it wreaked, then, by God, Berdyaev, regarding his agenda, would take his sweet time. Not for him the constant mobilized agitation, the sloganeering hysteria, the goose-stepping and dive-bombing spasms of modernity in full self-apocalypse. That is another characteristic of Berdyaev – he is all at once leisurely in style and apocalyptic in content. Berdyaev was quite as apocalyptic in his expository prose as his idol Fyodor Dostoevsky was in his ethical narrative, and being a voice of revelation he expressed himself, again like Dostoevsky, in profoundly religious and indelibly Christian terms. Berdyaev follows Dostoevsky and anticipates Alexander Solzhenitsyn in his conviction that no society can murder God, as Western secular society has gleefully done, and then go its insouciant way, without consequence. By the mid-1930s, in the extended aftermaths of World War I and the Bolshevik Revolution, and in the context of the ideological dictatorships, the conviction had impressed itself on Berdyaev that the existing Western arrangement, pathologically disordered, betokened the dissolution of civilization, not its continuance. In The Fate of Man in the Modern World, Berdyaev summarizes his discovery. In modernity, a brutal phase of history, the human collectivity must endure the effects of ancestral decisions, which subsequent generations might have altered but chose instead to endorse, and live miserably or perhaps die according to them. Modernity is thus history passing judgment on history, as Berdyaev sees it; and modernity’s brutality, its nastiness, and its inhumanity all stem from the same cause – the repudiation of God and the substitution in His place of a necessarily degraded “natural-social realm.” Berdyaev writes, “We are witnessing the socialization and nationalization of human souls, of man himself.” Some causes of this degeneracy lie proximate to their effects. “Modern bestialism and its attendant dehumanization are based upon idolatry, the worship of technics, race or class or production, and upon the adaptation of atavistic instincts to worship.” Again, “Dehumanization is… the mechanization of human life.” With mechanization comes also the “dissolution of man into… functions.”

By the mid-1930s, in the extended aftermaths of World War I and the Bolshevik Revolution, and in the context of the ideological dictatorships, the conviction had impressed itself on Berdyaev that the existing Western arrangement, pathologically disordered, betokened the dissolution of civilization, not its continuance. In The Fate of Man in the Modern World, Berdyaev summarizes his discovery. In modernity, a brutal phase of history, the human collectivity must endure the effects of ancestral decisions, which subsequent generations might have altered but chose instead to endorse, and live miserably or perhaps die according to them. Modernity is thus history passing judgment on history, as Berdyaev sees it; and modernity’s brutality, its nastiness, and its inhumanity all stem from the same cause – the repudiation of God and the substitution in His place of a necessarily degraded “natural-social realm.” Berdyaev writes, “We are witnessing the socialization and nationalization of human souls, of man himself.” Some causes of this degeneracy lie proximate to their effects. “Modern bestialism and its attendant dehumanization are based upon idolatry, the worship of technics, race or class or production, and upon the adaptation of atavistic instincts to worship.” Again, “Dehumanization is… the mechanization of human life.” With mechanization comes also the “dissolution of man into… functions.” One of the pleasures of reading backwards into the dissentient discussion of modernity is the discovery of contrarian judgments, such as Berdyaev’s concerning the Florentine revival of classicism, that stand in refreshing variance with existing conformist opinion. Will Durant sums up the standing textbook view of the Renaissance in Volume 5 (1953) of his Story of Civilization. When “the humanists captured the mind of Italy,” as Durant writes, they “turned it from religion to philosophy, from heaven to earth, and revealed to an astonished generation the riches of pagan thought and art.” Having accomplished all that, according once again to Durant, the umanisti reorganized education on the premise that “the proper study of man was now to be man, in all the potential strength and beauty of his body, in all the joy and pain of his senses and feelings, [and] in all the frail majesty of his reason.” Durant’s tone implies something beyond mere description; it implies laudatory approval. Before turning back to Berdyaev, it is worth remarking how obviously wrongheaded Durant is in so few words. Insofar as the umanisti adopted Platonism – or rather late Neo-Platonism – they cannot exactly be said exclusively to have “turned” the general attention “from heaven to earth.” Rather, they refocused that attention from the transcendent God of the Bible and the Church Doctors to the celestial powers of Porphryian cosmology, the ones who might be manipulated by magical formulas to serve their earthly masters. Now in adopting Protagoras’ maxim that, man is the measure, the umanisti did, in fact, “terrestrialize” thinking. They achieved their end, however, only at the cost of swapping a cosmic-teleological perspective for an egocentric-instrumental one. It was an act of self-demotion. Had Berdyaev lived to read Durant’s Renaissance, he himself would inevitably have remarked these easy-to-spot misconceptions.

One of the pleasures of reading backwards into the dissentient discussion of modernity is the discovery of contrarian judgments, such as Berdyaev’s concerning the Florentine revival of classicism, that stand in refreshing variance with existing conformist opinion. Will Durant sums up the standing textbook view of the Renaissance in Volume 5 (1953) of his Story of Civilization. When “the humanists captured the mind of Italy,” as Durant writes, they “turned it from religion to philosophy, from heaven to earth, and revealed to an astonished generation the riches of pagan thought and art.” Having accomplished all that, according once again to Durant, the umanisti reorganized education on the premise that “the proper study of man was now to be man, in all the potential strength and beauty of his body, in all the joy and pain of his senses and feelings, [and] in all the frail majesty of his reason.” Durant’s tone implies something beyond mere description; it implies laudatory approval. Before turning back to Berdyaev, it is worth remarking how obviously wrongheaded Durant is in so few words. Insofar as the umanisti adopted Platonism – or rather late Neo-Platonism – they cannot exactly be said exclusively to have “turned” the general attention “from heaven to earth.” Rather, they refocused that attention from the transcendent God of the Bible and the Church Doctors to the celestial powers of Porphryian cosmology, the ones who might be manipulated by magical formulas to serve their earthly masters. Now in adopting Protagoras’ maxim that, man is the measure, the umanisti did, in fact, “terrestrialize” thinking. They achieved their end, however, only at the cost of swapping a cosmic-teleological perspective for an egocentric-instrumental one. It was an act of self-demotion. Had Berdyaev lived to read Durant’s Renaissance, he himself would inevitably have remarked these easy-to-spot misconceptions. In The Meaning of the Creative Act, Berdyaev takes Benvenuto Cellini – a much-romanticized figure, using the adjective “romanticized” in its populist connotation – for one signal specimen of the “Renaissance Man.” Berdyaev is fully aware that describing the Renaissance simply as a revival of paganism amounts to inexcusable naïvety. “The great Italian Renaissance,” he writes, “is vastly more complex than is usually thought.” Berdyaev sees the so-called rebirth of classical letters and art as a botched experiment in dialectics, during which “there occurred such a powerful clash between pagan and Christian elements in human nature as had never occurred before.” The tragedy of the Renaissance consists in the fact, as Berdyaev insists, that, “the Christian transcendental sense of being had so profoundly possessed men’s nature that the integral and final confession of the immanent ideals of life became impossible.” Cellini embodies the conflict. In his life, no matter how declaredly “pagan,” “there is still too much of Christianity.” Cellini could never have been “an integral man,” as his moral degeneracy and spasmodic repentance attested. In Berdyaev’s argument, Christianity has effectuated, however imperfectly, a theurgic alteration in being towards a higher level. Cellini’s life illustrates the point. The attempt to return to being at a lower level must fail, as it failed for Cellini; it can bring only suffering to the subject and in the milieu that attempts it.

In The Meaning of the Creative Act, Berdyaev takes Benvenuto Cellini – a much-romanticized figure, using the adjective “romanticized” in its populist connotation – for one signal specimen of the “Renaissance Man.” Berdyaev is fully aware that describing the Renaissance simply as a revival of paganism amounts to inexcusable naïvety. “The great Italian Renaissance,” he writes, “is vastly more complex than is usually thought.” Berdyaev sees the so-called rebirth of classical letters and art as a botched experiment in dialectics, during which “there occurred such a powerful clash between pagan and Christian elements in human nature as had never occurred before.” The tragedy of the Renaissance consists in the fact, as Berdyaev insists, that, “the Christian transcendental sense of being had so profoundly possessed men’s nature that the integral and final confession of the immanent ideals of life became impossible.” Cellini embodies the conflict. In his life, no matter how declaredly “pagan,” “there is still too much of Christianity.” Cellini could never have been “an integral man,” as his moral degeneracy and spasmodic repentance attested. In Berdyaev’s argument, Christianity has effectuated, however imperfectly, a theurgic alteration in being towards a higher level. Cellini’s life illustrates the point. The attempt to return to being at a lower level must fail, as it failed for Cellini; it can bring only suffering to the subject and in the milieu that attempts it. Berdyaev emphasizes the drastic diremption of the Quattrocento by reminding his readers of the earliest, purely Christian phase of the Renaissance. “It was in mystic Italy, in Joachim de Floris, that the prophetic hope of a new world-epoch of Christianity was born, an epoch of love, and epoch of spirit.” The pre-perspective painters also loom large in Berdyaev’s appreciation: “Giotto and all the early religious painting of Italy, Arnolfi and others, followed St. Francis and Dante.” Where Raphael and Leonardo, as Berdyaev intimates, worked in a realm of literalism – copying from nature in a mechanical way – these earlier figures exercised their genius on the level of “symbolism.” In Berdyaev’s view, “mystic Italy” prefigures late-Nineteenth Century Symbolism, a movement that he found rich in meaning and hopeful in implication. Joachim, Dante, and St. Francis all violated what Berdyaev calls “the bounds of the average, ordered, canonic way”; their “revolt” precludes “any sort of compromise with the bourgeois spirit,” as did the later revolt of Charles Baudelaire, Henrik Ibsen, and Joris-Karl Huysmans. Whether it is Giotto or Baudelaire, the theurgic impulse aims, not to “create culture,” but to create “new being.”

Berdyaev emphasizes the drastic diremption of the Quattrocento by reminding his readers of the earliest, purely Christian phase of the Renaissance. “It was in mystic Italy, in Joachim de Floris, that the prophetic hope of a new world-epoch of Christianity was born, an epoch of love, and epoch of spirit.” The pre-perspective painters also loom large in Berdyaev’s appreciation: “Giotto and all the early religious painting of Italy, Arnolfi and others, followed St. Francis and Dante.” Where Raphael and Leonardo, as Berdyaev intimates, worked in a realm of literalism – copying from nature in a mechanical way – these earlier figures exercised their genius on the level of “symbolism.” In Berdyaev’s view, “mystic Italy” prefigures late-Nineteenth Century Symbolism, a movement that he found rich in meaning and hopeful in implication. Joachim, Dante, and St. Francis all violated what Berdyaev calls “the bounds of the average, ordered, canonic way”; their “revolt” precludes “any sort of compromise with the bourgeois spirit,” as did the later revolt of Charles Baudelaire, Henrik Ibsen, and Joris-Karl Huysmans. Whether it is Giotto or Baudelaire, the theurgic impulse aims, not to “create culture,” but to create “new being.” Caliban and emergent mechanical mastery taken together might well form an image to make one skip a breath. For once the “ebullience” of liberation-from-religion neutralizes “spiritual authority” and stimulates the “differentiation,” natural man, ego-driven and undisciplined, is bound to end up in possession of the Neo-Atlantean instrumentality, whereupon the prospect opens out on no end of mischief. Berdyaev’s historical diagnosis indeed runs in this direction. He even formulates the law of what he calls “the strange paradox”: “Man’s self-affirmation leads to his perdition; the free play of human forces unconnected with any higher aim brings about the exhaustion of man’s creative powers.” The Protestant Reformation of the German North and the so-called Enlightenment of the Eighteenth Century in France and the German states represent, in Berdyaev’s scheme, ever-lower stages of this descent into dissolution rather than the steps-upward of the ready version of Progress. The paradox of humanism consists in its having “affirmed man’s self-confidence” while also having “debased [man] by ceasing to regard him as a being of a higher and divine origin.”

Caliban and emergent mechanical mastery taken together might well form an image to make one skip a breath. For once the “ebullience” of liberation-from-religion neutralizes “spiritual authority” and stimulates the “differentiation,” natural man, ego-driven and undisciplined, is bound to end up in possession of the Neo-Atlantean instrumentality, whereupon the prospect opens out on no end of mischief. Berdyaev’s historical diagnosis indeed runs in this direction. He even formulates the law of what he calls “the strange paradox”: “Man’s self-affirmation leads to his perdition; the free play of human forces unconnected with any higher aim brings about the exhaustion of man’s creative powers.” The Protestant Reformation of the German North and the so-called Enlightenment of the Eighteenth Century in France and the German states represent, in Berdyaev’s scheme, ever-lower stages of this descent into dissolution rather than the steps-upward of the ready version of Progress. The paradox of humanism consists in its having “affirmed man’s self-confidence” while also having “debased [man] by ceasing to regard him as a being of a higher and divine origin.” Berdyaev certainly never stood alone in his diagnosis of modern despiritualization. Similar if not identical insights occur under the scrutiny not only of the other writers mentioned at the outset (from Blixen to Undset) but more recently in the work of Jacques Barzun (especially in his great late-career book, From Dawn to Decadence), Roberto Calasso, Jacques Ellul, René Girard, Paul Gottfried, Kenneth Minogue, Roger Scruton, and Eric Voegelin, to name but a few more or less at random. Yet however many names one crowds together in a sentence, the shared judgment remains in the minority and under exclusion. In the prevailing liberal-progressive view, the world is monistic and one-dimensional: Everything is race, class, gender, or the state. In Berdyaev’s dissenting view, the world is dualistic and three-dimensional: “Christianity reveals and confirms man’s belonging to two planes of being, to the spiritual and to the natural-social, to the Kingdom of God and the Kingdom of Caesar.” It is the first dimension – actually a double dimension – of height and depth that guarantees freedom in the second dimension. The denial of the realm of height and depth is therefore the essence, a totally negative essence, of the Kingdom of Caesar intransigent. Berdyaev values man over society because he values spirit over matter,” the sole concern of men on the “natural-social” plane. The existing society indeed values matter exclusively, to the extent of having fixated itself on the finished product – the latest cell phone or handheld electronic game-player or that contradiction-in-the-adjective, the smart car – while deputizing foreign nations to produce these things. This same society, a kind of super cargo-cult, deracinated, demoralized, despiritualized, badly educated, deluged in pornography and ideology, and as conformist as any primitive tribe, vigorously denies the spirit, where not explicitly as articulate theory then in behavior.

Berdyaev certainly never stood alone in his diagnosis of modern despiritualization. Similar if not identical insights occur under the scrutiny not only of the other writers mentioned at the outset (from Blixen to Undset) but more recently in the work of Jacques Barzun (especially in his great late-career book, From Dawn to Decadence), Roberto Calasso, Jacques Ellul, René Girard, Paul Gottfried, Kenneth Minogue, Roger Scruton, and Eric Voegelin, to name but a few more or less at random. Yet however many names one crowds together in a sentence, the shared judgment remains in the minority and under exclusion. In the prevailing liberal-progressive view, the world is monistic and one-dimensional: Everything is race, class, gender, or the state. In Berdyaev’s dissenting view, the world is dualistic and three-dimensional: “Christianity reveals and confirms man’s belonging to two planes of being, to the spiritual and to the natural-social, to the Kingdom of God and the Kingdom of Caesar.” It is the first dimension – actually a double dimension – of height and depth that guarantees freedom in the second dimension. The denial of the realm of height and depth is therefore the essence, a totally negative essence, of the Kingdom of Caesar intransigent. Berdyaev values man over society because he values spirit over matter,” the sole concern of men on the “natural-social” plane. The existing society indeed values matter exclusively, to the extent of having fixated itself on the finished product – the latest cell phone or handheld electronic game-player or that contradiction-in-the-adjective, the smart car – while deputizing foreign nations to produce these things. This same society, a kind of super cargo-cult, deracinated, demoralized, despiritualized, badly educated, deluged in pornography and ideology, and as conformist as any primitive tribe, vigorously denies the spirit, where not explicitly as articulate theory then in behavior.