The Legacy of a European Traditionalist: Julius Evola in Perspective

Guido Stucco

This article is a brief introduction to the life and central ideas of the controversial Italian thinker Julius Evola (1898-1974), one of the leading representatives of the European right and of the “Traditionalist movement” 1 in the twentieth century. This movement, together with the Theosophical Society, played a leading role in promoting the study of ancient eastern wisdom, esoteric doctrines, and spirituality. Unlike the Theosophical Society, which championed democratic and egalitarian views,2 an optimistic view of progress, and a belief in spiritual evolution, the Traditionalist movement adopted an elitist and antiegalitarian stance, a pessimistic view of ordinary life and of history, and an uncompromising rejection of the modern world. The Traditionalist movement began with René Guénon (1886-1951), a French philosopher and mathematician who converted to Islam and moved to Cairo in 1931, following the death of his first wife. Guénon revived interest in the concept of Tradition, i.e., the teachings and doctrines of ancient civilizations and religions, emphasizing its perennial value over and against the “modern world” and its offshoots: humanistic individualism, relativism, materialism, and scientism. Other important Traditionalists of the past century have included Ananda Coomaraswamy, Frithjof Schuon, and Julius Evola.

This article is addressed, first, to persons who claim to be conservative and of rightist persuasion. It is my contention that Evola’s political views can help the American right to acquire a greater intellectual relevance and to overcome its provincialism and narrow horizons The criticism most frequently leveled by the European “New Right“ against American conservatives is that the ideological poverty of the American Right lies in its circling its wagons around a conservative agenda, in its inability to see the greater scheme of things.3 By disclosing to his readers the value and worth of the world of Tradition, Evola has shown that to be a rightist entails much more than taking a stance on civic and social issues, such as abortion, capital punishment, a strong military, free enterprise, less taxes, less government, fierce patriotism, and the right to bear arms, but rather assessing more crucial matters involving race, ethnicity, eugenics, immigration, and the nature of the nation-state.

Second, readers with an active interest in spiritual and metaphysical matters may find Evola’s thought insightful and his exposition of ancient esoteric techniques very helpful. Moreover, his views, though at times very discriminatory, have the potential of becoming a catalyst for personal transformation and spiritual growth.

To date, Evola’s work has been subjected to the silent treatment. When Evola is not ignored, he is usually vilified by leftist scholars and intellectuals, who demonize him as a bad teacher, racist, rabid anti-Semite, master mind of right-wing terrorism, fascist guru, or so filthy a racist even to touch him would be repugnant. The writer Martin Lee, whose knowledge of Evola is of the most superficial sort, called him a “Nazi philosopher” and claimed that “Evola helped compose Italy’s belated racialist laws toward the end of the Fascist rule.4 Others have minimized his contribution altogether. Walter Laqueur, in his Fascism: Past, Present, Future, did not hesitate to call him a “learned charlatan, an eclecticist, not an innovator,” and suggested “there were elements of pure nonsense also in his later work.”5 Umberto Eco sarcastically nicknamed Evola “Othelma, the Magician.”

The most valuable summaries to date of Evola’s life and work in the English language have been written by Thomas Sheehan and Richard Drake.6 Until either a biography of Evola or his autobiography becomes available to the English-speaking world, these articles remain the best reference sources for his life and work. Both scholars are well versed in Italian culture, politics, and language. Although not sympathetic to Evola’s ideas, they were the first to introduce the Italian thinker’s views to the American public. Unfortunately, their interpretations of Evola’s work are very reductive. Sheehan and Drake succumb to the dominant leftist propaganda according to which Evola is a “bad teacher” because he allegedly supplied ideological justification for a bloody campaign by right wing terrorists in Italy during the 1980s.7 Regrettably, both authors have underestimated Evola’s spissitudo spiritualis as an esotericist and a Traditionalist, and have written about Evola merely as a case study in their fields of competence, i.e., philosophy and history, respectively.8

Despite his many detractors, Evola has enjoyed something of a revival in the past twenty years. His works have been translated into French, German,9 Spanish, and English, as well as Portuguese, Hungarian, and Russian. Conferences devoted to the study of this or that aspect of Evola’s thought are mushrooming everywhere in Europe.10 Thus, paraphrasing the title of Edward Albee’s play, we may want to ask: “Who’s afraid of Julius Evola?” And, most important, why?

Evola’s Life

Julius Evola died of heart failure at his Rome apartment on June 11, 1974, at the age of seventy-six. Before he died he asked to be seated at his desk in order to face the sun’s light streaming through the open window. In accordance with his will, his body was cremated and the urn containing his ashes was buried in a crevasse on Monte Rosa, in the Italian Alps.

Evola’s writing career spanned more than half a century. It is possible to distinguish three periods in his intellectual development. First came an artistic period (1916-1922), during which he embraced dadaism and futurism, wrote poetry, and painted in the abstract style. The reader may recall that dadaism was an avant-garde movement founded by Tristan Tzara, characterized by a yearning for absolute freedom and by a revolt against all prevalent logical, ethical, and aesthetic canons.

Evola turned next to the study of philosophy (1923-1927), developing an ingenuous perspective that could be characterized as “transidealistic,” or as a solipsistic development of mainstream idealism. After learning German in order to be able to read the original texts of the main idealist philosophers (Schelling, Fichte, and Hegel), Evola accepted their chief premise, that being is the product of thought. Yet he also attempted to overcome the passivity of the subject toward “reality” typical of idealist philosophy and of its Italian offshoots, represented by Giovanni Gentile and Benedetto Croce, by outlining the path leading to the “Absolute Individual,” to the status enjoyed by one who succeeds in becoming free (ab-solutus) from the conditionings of the empirical world. During this period Evola wrote Saggi sull’idealismo magico (Essays on magical idealism), Teoria dell’individuo assoluto (Theory of the absolute individual), and Fenomenologia dell’individuo assoluto (Phenomenology of the absolute individual), a massive work in which he employs the values of freedom, will, and power to expound his philosophy of action. As the Italian philosopher Marcello Veneziani wrote in his doctoral dissertation: “Evola’s absolute I is born out of the ashes of nihilism; with the help of insights derived from magic, theurgy, alchemy and esotericism, it ascends to the highest peaks of knowledge, in the quest for that wisdom that is found on the paths of initiatory doctrines.”11

In the third and final phase of his intellectual formation, Evola became involved in the study of esotericism and occultism (1927-1929). During this period he cofounded and directed the so-called Ur group, which published monthly monographs devoted to the presentation of esoteric and initiative disciplines and teachings. “Ur” derives from the archaic root of the word “fire”; in German it also means “primordial” or “original.” In 1955 these monographs were collected and published in three volumes under the title Introduzione alla magia quale scienza dell’Io.12 In the over twenty articles Evola wrote for the Ur group, under the pseudonym “EA” (Ea in ancient Akkadian mythology was the god of water and wisdom) and in the nine articles he wrote for Bylichnis (the name signifies a lamp with two wicks), an Italian Baptist periodical, Evola laid out the spiritual foundations of his world view.

During the 1930s and 1940s Evola wrote for a number of journals and published several books. During the Fascist era he was somewhat sympathetic to Mussolini and to fascist ideology, but his fierce sense of independence and detachment from human affairs and institutions prevented him from becoming a card-carrying member of the Fascist party. Because of his belief in the supremacy of ideas over politics and his aristocratic and anti-populist views, which at times conflicted with government policy—as in his opposition to the 1929 Concordat between the Italian state and Vatican and to the “demographic campaign” launched by Mussolini to increase Italy’s population—Evola fell out of favor with influential Fascists, who shut down La Torre (The tower), the biweekly periodical he had founded, after only ten issues (February-June 1930).13

Evola devoted four books to the subject of race, criticizing National Socialist biological racism and developing a doctrine of race on the basis of the teachings of Tradition: Il mito del sangue (The myth of blood); Sintesi di una dottrina della razza (Synthesis of a racial doctrine); Tre aspetti del problema ebraico (Three aspects of the Jewish question); Elementi di una educazione razziale (Elements of a racial education). In these books the author outlined his tripartite anthropology of body, soul, and spirit. The spirit is the principle that determines one’s attitude toward the sacred, destiny, life and death. Thus, according to Evola, the cultivation of the “spiritual race” should take precedence over the selection of the somatic race, which is determined by the laws of genetics and with which the Nazis were obsessed. Evola’s antimaterialistic and non-biological racial views won Mussolini’s enthusiastic endorsement. The Nazis, for their part, were suspicious of and even critical of Evola’s “nebulous” theories, accusing him of watering down the empirical, biological element to promote an abstract, spiritualist, and semi-Catholic view of race.

Before and during World War II, Evola traveled and lectured in several European countries, practicing mountain climbing as a spiritual exercise in his spare time. After Mussolini was freed from his Italian captors in a daring German raid led by SS-Hauptsturmführer Otto Skorzeny, Evola was among a handful of faithful followers who met him at Hitler’s headquarters in Rastenburg, East Prussia, on September 14, 1943. While sympathetic to the newly formed Fascist government in the north of Italy, which continued to fight on the Germans‘ side against the Allies, Evola rejected its republican and socialist agenda, its populist style, and its antimonarchical sentiments.

When the Allies entered Rome in June 1944, their secret services attempted to arrest Evola, who was living there at the time. As his elderly mother stalled the MPs, Evola slipped out of the door undetected, and made his way to northern Italy, and then to Austria. While in Vienna, he began to study secret archives confiscated from various European Masonic lodges by the Germans.

One day in 1945, as Evola was walking the deserted streets of the Austrian capital during a Soviet air attack, a bomb exploded a few yards away from him. The blast threw him against a wooden plank. Evola fell on his back, and awoke in the hospital. He had suffered a compression of the bone marrow, paralyzing him from the waist down. Common sense tells one that walking a city’s deserted streets during aerial bombardments is madness, if not suicide. But Evola was used to courting danger. Or, as he once put it, to follow “the norm of not avoiding dangers, but on the contrary, to seek them out, [i]s an implicit way of questioning fate.”14 That is not to say that he believed in “blind” fate. As he once wrote:

There is no question that one is born with certain tendencies, vocations and pre-dispositions, which at times are very obvious and specific, though at other times are hidden and likely to emerge only in particular circumstances or trials. We all have a margin of freedom in regard to this innate, differentiated element. 15

Evola was determined to question his fate, especially at a time when an entire era was coming to an end.16 But what he had anticipated during the air raid was either death or the attainment of a new perspective on life, not paralysis. He struggled for a long time with that particular outcome, trying to make sense of his “karma”:

Remembering why I had willed it [i.e., the paralysis] and to understand its deeper meaning was to me the only thing that ultimately mattered, something far more important than to “recover,“ to which I never really attributed much importance anyway.17

Evola had ventured outdoors during the air raid in order to test his fate, for he firmly believed in the Traditional, classical doctrine that all the major events that occur in our lives are not purely casual or the outcome of our efforts, but rather the deliberate result of a prenatal choice, something that has been willed by “us” before we were born.

Three years prior to his paralysis, Evola wrote:

Life here on earth cannot be viewed as a coincidence. Moreover, it should not be regarded as something we can either accept or reject at will, nor as a reality that imposes itself on us, before which we can only remain passive, or display an attitude of obtuse resignation. Rather, what arises in some people is the sensation that earthly life is something to which, prior to our becoming terrestrial beings, we have committed ourselves, both as an adventure and as a mission or a chosen task, undertaking a whole set of problematic and tragic elements as well.18

There followed a five-year period of inactivity. First, Evola spent a year and a half in a Vienna hospital. In 1948, thanks to the intervention of a friend with the International Red Cross, he was sent back to Italy. He stayed in a hospital in Bologna for at least another year, where he underwent an unsuccessful laminectomy (a surgical procedure in which part of a vertebra is removed in order to relieve pressure on the nerves of the spinal cord). Evola returned to his Roman residence in 1949, where he lived as an invalid for the next twenty-five years.

While in Bologna, Evola was visited by his friend Clemente Rebora, a poet who became a Christian, and then a Catholic priest in the order of the Rosminian Fathers. After reading about their friendship in one of Evola’s works, in 1997 I visited the headquarters of the order and asked to talk to the person in charge of Rebora’s archives, in hopes of discovering a previously unknown correspondence between them. No correspondence surfaced, but the priest in charge of the archive was kind enough to give me a copy of a couple of letters Rebora wrote to a friend concerning Evola. The following summary of those letters is revealing of Evola’s view of religion, and of Christianity in particular.19

In 1949 a fellow priest, Goffredo Pistoni, solicited Rebora to visit Evola. Rebora asked permission of his provincial superior, and upon receiving it traveled from Rovereto to Evola's hospital in Bologna. Rebora was animated by the desire to see Evola embrace the Christian faith and intended to be a good witness of the gospel. In a letter to Pistoni, Rebora asked for his assistance so that he would not spoil the “most merciful ways of Infinite Love, and, if [my visit was to be] unhelpful, at least not [turn out to be] harmful.” On March 20, 1949, Rebora wrote to his friend Pistoni on the letterhead of the Salesian Institute of Bologna:

I have just returned from our Evola: we talked at great length and left each other in a brotherly mood, though I did not detect any visible change on his part which after all I could not expect. I have felt him to be like one yearning to “join the rest of the army,” as he said himself, waiting to see what will happen to him. . . . I have sensed in him a thirst for the absolute, which nevertheless eludes Him who said: “Let anyone who is thirsty come to me and drink.”20

Rebora’s frustration with Evola’s unwillingness to abandon his views and embrace the Christian faith is evident in the comment with which he closes the first half of his letter:

Let us pray that his previous books, which he is about to reprint, and a few new titles that will be published soon, may not chain him down, considering the success they have, and may not damage people’s souls, leading them astray in the direction of a false spirituality, as they “follow false images of the Good.” [Probably a quote from Dante’s Divine Comedy. —G.S.]

Rebora concluded his letter on May 12, 1949, adding:

Having returned to headquarters I am finally concluding this letter by telling you that a supernatural tenderness is growing in my heart for him. He [Evola] told me about an inner event that occurred to him during the bombing of Vienna, which, he added, is still mysterious to him, as he undergoes this present trial. On the contrary, I trust I am able to detect the providential and decisive meaning of this event for his soul.

Rebora wrote again to Evola, asking him if he was willing to travel to Lourdes on a special train on which Rebora served as a spiritual director. Evola politely refused and the contact between the two eventually ended. Evola never converted to Christianity. In a 1935 letter written to a friend of his, Girolamo Comi, another poet who had become a Christian, Evola claimed:

As far as I am concerned, in regard to the “conversion” that really matters, and not that which is based on feelings or on a religious faith, I have been all right since thirteen years ago [i.e., 1922, the transition year between the artistic and philosophical periods].21

René Guénon wrote to the convalescent Evola22 suggesting that the latter had been the victim of a curse or magical spell cast by some powerful enemy. Evola replied that he considered that unlikely, for the circumstances to be summoned (e.g., the exact moment of the bomb’s landing, the place where Evola happened to be at that moment), would have required too powerful a spell. Mircea Eliade, the renowned historian of religion, who corresponded with Evola throughout his life, once remarked to one of his own students: “Evola was wounded in the third chakra—and don’t you find that significant?”23 Since the corresponding affective forces of the third chakra are anger, violence, and pride, one may wonder whether Eliade meant that the wound sustained by Evola could have had a purifying effect on the Italian thinker, or whether it was the consequence of his hubris. In any event, Evola rejected the idea that his paralysis was a sort of “punishment” for his “promethean” efforts in the spiritual domain. For the rest of his life he endured his condition with admirable stoicism, in rigorous coherence with his beliefs.24

For the next two decades Evola received visitors, friends, and young people who regarded themselves his disciples. According to Gianfranco de Turris, who met him for the first time in 1967, one could sense that he was a “person of high caliber,” though he did not show off or assume snobbish attitudes. Evola would wear a monocle and rest his cheek on a clenched fist, observing his visitor with curiosity. He did not like the idea of having “disciples,” and jokingly referred to his admirers as “Evolomani” (“Evola maniacs”). In not seeking to recruit followers, he was probably mindful of Buddha’s injunction to proclaim the truth without attempting to persuade or dissuade: “One should know approval and one should know disapproval, and having known approval, having known disapproval, one should neither approve nor disapprove, one should simply teach dhamma.”25

Central Themes in Evola’s Thought

In Evola’s literary production it is possible to single out three major themes, which are strictly interwoven and mutually dependent. These themes represent three facets of his philosophy of action. I have designated these themes with terms borrowed from ancient Greek. The first theme is xeniteia, a word that refers to the condition of living abroad, or of being absent from one’s homeland. In Evola’s works one can easily detect a sense of alienation, of not belonging to what he called the “modern world.” According to ancient peoples, xeniteia was not an enviable condition. To live surrounded by barbarous people and customs, away from one’s polis, when not the result of a personal choice was often the result of a judicial sentence. We may recall that exile was often meted out to undesirable elements of an ancient society, e.g., the short-lived practice of ostracism in ancient Athens; the fate that befell many ancient Romans, including the Stoic philosopher Seneca; the deportation of entire families or populations, etc.

Throughout his life, Evola never really “fit in.” Whether during his artistic, philosophical, or esoteric phase, he always felt like a straggler, seeking to link up with “the rest of the ‘army.’” The modern world he denounced in his masterpiece, Revolt against the Modern World, took its revenge on him: at the end of the war he was surrounded by a world of ruins, isolated, avoided, and reviled. Yet he managed to retain a composed, dignified attitude and to continue in his self-appointed task of night-watchman.

The second theme is apoliteia, or abstention from active participation in the construction of the human polis. Evola’s recommendation was that while living in exile from the world of Tradition and from the Golden Age, one should avoid the encroaching embrace of the multitudes and refrain from active participation in ordinary human affairs. Apoliteia, according to Evola, refers essentially to an inner attitude of indifference and detachment, but it does not necessarily entail a practical abstention from politics, as long as one engages in it with a completely detached attitude: “Apoliteia is the inner, irrevocable distance from this society and its ‘values’: it consists in not accepting being bound to society by any spiritual or moral bond.”26 This attitude is to be commended because, according to Evola, in this day and age there are no ideas, causes, and goals worthy of one’s commitment.

Finally, the third theme is autarkeia, or self-sufficiency. The quest for spiritual independence led Evola far away from the busy crossroads of human interaction, in order to explore and expound paths of perfection and of asceticism. He became a student of ancient esoteric and occult teachings on “liberation,” and published his findings in several books and articles.

Xeniteia

The following words, spoken by the Benevolent Spirit to the Destructive Spirit in the Yasna, a Zoroastrian collection of hymns and prayers, may serve to characterize Evola’s attitude toward the modern world: “Neither our thoughts, nor teachings, nor intentions, neither our preferences nor words, neither our actions nor conceptions nor our souls are in accord.”27 Throughout his entire life Evola lived in a consistent and coherent fashion that could be simplistically dismissed as intellectual snobbism or even misanthropy. But the reasons for Evola’s rejection of the socio-political order in which lived must be sought elsewhere, namely in a well-articulated Weltanschauung, or worldview.

To be sure, Evola’s sense of estrangement from the society in which he lived was reciprocated. Anyone who refuses to recognize the legitimacy of “the System,” or to participate in the life of a community which he does not recognize as his own, professing instead a higher allegiance to and citizenship in another land, world, or ideology, is bound to live like a metic in ancient Greece, surrounded by suspicion and hostility.28 In order to understand the reasons for Evola’s uncompromising attitude, we need first to define the concepts of “Tradition” and “modern world” as employed by Evola in his works.

Generally speaking, the term tradition can be understood in several ways: (1) as an archetypal myth (some members of the political Right in Italy have rejected this view as an “incapacitating myth”); (2) as the way of life of a particular age, e.g., the Middle Ages, feudal Japan, the Roman Empire; (3) as the sum of three principles: “God, Country, Family”; (4) as anamnesis, or historical memory in general; and (5) as a body of religious teachings to be preserved and transmitted to future generations. Evola understood tradition mainly as an archetypal myth, that is, as the presence of the Absolute in specific historical and political forms. Evola’s Absolute is not a religious principle or a noumenon, much less the God of theism, but rather a mysterious domain, or dunamis, power. Evola’s Tradition is characterized by “Being” and stability, while the modern world is characterized by “Becoming.” In the world of tradition stable socio-political institutions were in place. The world of Tradition, according to Evola, was exemplified by the ancient Roman, Greek, Indian, Chinese, and Japanese civilizations. These civilizations upheld a strict caste system; they were ruled by warrior nobilities and waged wars to expand the boundaries of their imperiums. In Evola’s words:

The traditional world knew divine kingship. It knew the bridge between the two worlds, namely initiation. It knew the two great ways of approach to the transcendent, namely heroic action and contemplation. It knew the mediation, namely rites and faithfulness. It knew the social foundation, namely the traditional law and the caste system. And it knew the political earthly symbol, namely the empire.29

Evola claims that the traditional world’s underlying belief was the “invisible”:

It held that mere physical existence, or “living,” is meaningless unless it approximates the higher world or that which is “more than life,” and unless one’s highest ambition consists in participating in hyperkosmia and in obtaining an active and final liberation from the bond represented by the human condition.30

Evola upheld a cyclical view of history, a philosophical and religious view with a rich cultural heritage. Though one may reject it, this view deserves as much respect as the linear view of history upheld by theism, to which I subscribe, or as the progressive view championed by Engels’ “scientific materialism,” or as the hopeful and optimistic view typical of various New Age movements, according to which the universe is undergoing a constant and irreversible spiritual evolution. According to the cyclical view of history espoused by Hinduism, which Evola adopted and modified to fit his views, we are living in the fourth age of a complete cycle, the so-called Kali-yuga, an era characterized by decadence and disruption. According to Evola, the most remarkable phases of this “Yuga” (era) included the emergence of pre-Socratic philosophy (characterized by rejection of myth and by overemphasis on reason); the birth of Christianity; the Renaissance; Humanism; the Protestant Reformation; the Enlightenment; the French Revolution; the European revolutions of 1848; the advent of the Industrial Revolution; and Bolshevism. Thus, the “modern world” for Evola did not begin in the 1600s, but rather in the fourth century B.C.

Evola and Eliade

Evola’s rejection of the modern world can be contrasted with its acceptance, promoted by Mircea Eliade (1907-1986), the renowned historian of religion whom Evola met in person several times, and with whom he corresponded until his death in 1974. The two men met for the first time in 1937. By that time, Eliade had compiled an impressive academic record that included a bachelor’s degree in philosophy from the University of Bucharest and an M.A. and a Ph.D. in Sanskrit and Indian philosophy from the University of Calcutta. Evola was already an accomplished writer and had published some of his most important works, such as The Hermetic Tradition (1931), Revolt against the Modern World (1934), and The Mystery of the Grail (1937).31

Eliade had read Evola’s early philosophical works during the 1920s and “admired his intelligence and, even more, the density and clarity of his prose.”32 An intellectual friendship developed between the young Romanian scholar and the Italian philosopher, who was nine years Eliade’s senior. Their common interest in yoga led Evola to write L’uomo e la potenza (Man as power) in 1926 (revised in 1949 with the new title The Yoga of Power 33) and Eliade to write the acclaimed scholarly work Yoga: Immortality and Freedom (1933). As Eliade recalls in his autobiographical journals:

I received letters from him when I was in Calcutta (1928-31) in which he instantly begged me not to speak to him of yoga, or of “magical powers” except to report precise facts to which I had personally been a witness. In India I also received several publications from him, but I only remember a few issues of the journal Krur.34

Evola and Eliade’s first meeting was in Romania, in conjunction with a luncheon hosted by the philosopher Nae Ionescu. Evola was traveling through Europe at the time, establishing contacts, and giving lectures “in the attempt to coordinate those elements who could represent, to some degree, the [T]raditional thought on the political-cultural plane.”35 Eliade recalled the admiration that Evola expressed for Corneliu Codreanu (1899-1938), the founder of the Romanian nationalist and Christian movement known as the “Iron Guard.” Evola and Codreanu had met the morning of the luncheon. Codreanu told Evola of the effects that incarceration had had on his soul, and of his discovery of contemplation in the solitude and silence of his prison cell. In his autobiography Evola described Codreanu as “one of the worthiest and most spiritually oriented persons I ever met in the nationalist movements of that period.36 Eliade wrote that at the luncheon “Evola was still dazzled by him [Codreanu]. I vaguely remember the remarks he made then on the disappearance of contemplative disciplines in the political battle of the West.”37 But the two scholars’ focus was different indeed. As Eliade wrote in his journal:

One day I received a rather bitter letter from him, in which he reproached me for never citing him, no more than did Guénon. I answered him as best as I could, and I must one day give reasons and explanations that that response called for. My argument could not have been simpler. The books I write are intended for today’s audience, and not for initiates. Unlike Guénon and his emulators, I believe I have nothing to write that would be intended especially for them.38

I must conclude from Eliade’s remarks that he did not like, share, or care for Evola’s esoteric views and leanings. I believe there are three reasons for Eliade’s aversion. First, Evola, like all traditionalists, presumed the existence of a higher, solar, royal, and esoteric primordial tradition, and devoted his life to describing, studying, and celebrating it in its many forms and varieties. He also set this tradition above and against what he dubbed “telluric” modern popular cultures and civilizations (such as Romania’s, to which Eliade belonged). In Revolt against the Modern World one can read many instances of this juxtaposition.

Eliade, for his part, rejected any emphasis on esotericism, because he thought it had a reductive effect on the human spirit. Eliade claimed that to limit the value of European spiritual creations exclusively to their “esoteric meanings” repeated in reverse the reductionism of the materialistic approach adopted by Marx and Freud. Nor did he believe in the existence of a primordial tradition: “I was suspicious of its artificial, ahistorical character,” he wrote.39 Second, Eliade rejected the negative or pessimistic view of the world and the human condition that characterized Guénon’s and Evola’s thought. Unlike Evola, who believed in the ongoing “putrefaction” of contemporary Western culture, Eliade claimed:

[T]o the extent that I . . . believe in the creativity of the human spirit, I cannot despair: culture, even in a crepuscular era, is the only means of conveying certain values and of transmitting a certain spiritual message. In a new Noah’s Ark, by means of which the spiritual creation of the West could be saved, it is not enough for René Guénon’s L’esotérisme de Dante to be included; there must be also the poetic, historic, and philosophical understanding of The Divine Comedy.40

Finally, the socio-cultural milieu that Eliade celebrated was very different from the one favored by Evola. As India regained its independence, Eliade came to believe that Asia was about to re-enter history and world politics and that his own people, the Romanians, “could fulfill a definite role in the coming dialogue between the [] West, Asia and cultures of the archaic folk type.”41 He celebrated the peasant roots of Romanian culture as they promoted universalism and pluralism, rather than nationalism and provincialism. Eliade wrote:

It seemed to me that I was beginning to discern elements of unity in all peasant cultures, from China and South-East Asia to the Mediterranean and Portugal. I was finding everywhere what I later called “cosmic religiosity”: that is, the leading role played by symbols and images, the religious respect for earth and life, the belief that the sacred is manifested directly through the mystery of fecundity and cosmic repetition. . . .42

These conclusions could not have been more diametrically opposed to Evola’s views, especially as he formulated them in Revolt against the Modern World. According to the latter’s doctrine, cosmic religiosity is an inferior and corrupt form of spirituality, or, as he called it, a “lunar spirituality” (the moon, unlike the sun, is not a source of light, and merely reflects the latter’s light, as “lunar spirituality” is contingent upon God, the All, or upon any other metaphysical version of the Absolute) characterized by mystical abandonment.

In his yet untranslated autobiography, Il cammino del cinabro (“The cinnabar’s journey”), Evola describes his spiritual and intellectual journey through alien landscapes: religious (Christianity, theism), philosophical (idealism, nihilism, realism), and political (democracy, Fascism, post-war Italy). For readers who are not familiar with Hermeticism, we may recall that cinnabar is a red metal representing rubedo, or redness, which is the third and final stage of one’s inner transformation. Evola explains at the beginning of his autobiography: “My natural sense of detachment from what is human in regard to many things that, especially in the affective domain, are usually regarded as `normal,‘ was manifested in me at a very tender age.”43

Autarkeia

Various religions and philosophies regard the human condition as highly problematic, likening it to a disease and setting forth a cure. This disease is characterized by many features, including a certain spiritual “heaviness,” or gravitational pull, drawing us “downwards.” Humans are prisoners of meaningless daily routines; of pernicious habits developed over years, e.g., drinking, smoking, gambling, workaholism, and sexual addictions, in response to external pressures; of an intellectual and spiritual laziness that prevents us from developing our powers and becoming living, vibrant beings; and of inconstancy, as is often painfully obvious from our ever-renewed “New Year’s resolutions.” How often, when we commit ourselves to practice something on a daily basis over a period of time, does the day soon come that we forget, find an excuse to abandon our commitment, or simply quit! This is not merely inconsistency or a lack of perseverance on our part: it is a symptom of our inability to master ourselves and our lives.

Moreover, we are by nature unable to keep our minds focused on any object of meditation. We are easily distracted and bored. We spend our days talking about unimportant, meaningless details. Our conversations, for the most part, are not real dialogues, but rather exchanges of monologues.

We are busy at jobs we do not care about, and earning a living is our utmost concern. We feel bored, empty, and sexually frustrated by our own or our partners’ inability to deliver peak performance. We want more: more money, more leisure, more “toys,” and more fulfillment, of which we get too little, too seldom. We succumb to all sorts of indulgences and petty pleasures to soothe our dull and wounded consciousness. And yet all these things are merely symptoms of the real problem that besets the human condition. Our real problem is not that we are deficient beings, but that we don’t know how to be, and don’t desire to be, different. We embrace everyday life and call it “the real thing,” slowly but inexorably suffocating the yearning for transcendence buried deep within us. In the end this proves to be our real undoing; we are not unlike smokers who, after being diagnosed with emphysema, keep on smoking to the bitter end. The problem is that we deny there is a problem. We are like a psychotic person who denies he is mentally ill, or like a sociopath who after committing a heinous crime insists that he really has a conscience, producing tears and remorse to prove it.

In the past, movements like Pythagoreanism, Gnosticism, Manichaeism, Mandaeanism, and medieval Catharism claimed that the problem beleaguering human beings is the body itself, or physical matter, to be precise. These movements held that the soul or spirit is kept prisoner inside the cage of matter, waiting to be freed. (Evola rejected this interpretation as unsophisticated and as the product of a feminine and telluric worldview.) Buddhism declared a “polluted” or “unenlightened mind” to be the real problem, developing in the course of the centuries a real science of the mind in an attempt to cure the disease at the roots. Christian theism identified the root of human suffering and evil in sin. As a remedy, Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy propose incorporation into the church through baptism and active participation in her liturgical life. Many Protestants advocate, instead, a living and personal relationship with Jesus Christ as one’s Lord and Savior, to be cultivated through prayer, Bible studies, and church fellowship.

Evola regarded acceptance of the human condition as the real problem, and autarchy, or self-sufficiency, as the cure. According to the ancient Cynics, autarkeia is the ability to lead a satisfactory, full life with the least amount of material goods and pleasures. An autarchic being (the ideal man) is a person who is able to grow spiritually even in the absence of what others consider the necessities of life (e.g., health, wealth, and good human relationships). The Stoics equated autarchy with virtue (arête, which they regarded as the only thing needed for happiness. Even the Epicureans, led though they were by a quest for pleasure, regarded autarkeia as a “great good, not with the aim of always getting by with little, but that if much is lacking, we may be satisfied with little.”44

Evola endorsed the notion of autarkeia out of his rejection of the human condition and of the ordinary life that stems from it. Like Nietzsche before him, Evola claimed that the human condition and everyday life should not be embraced, but overcome: our worth lies in being a “project” (in Latin projectum, “to be cast forward"). Thus, what truly matters for human beings is not who we are but what we can and should become. Humans are enlightened or unenlightened according to whether or not they grasp this basic metaphysical truth. It was not snobbism that led Evola to conclude that most human beings are “slaves” trapped in samsara like guinea pigs running on a wheel inside their cage. According to Evola, sharing this state, among those one encounters each day, are not only persons with low paying jobs, but also one’s coworkers, family members, and especially persons without a formal education. This is of course difficult to acknowledge. Evola was consumed by a yearning for what the Germans call mehr als leben (“more than living”), which is unavoidably frustrated by the contingencies of human existence. We read in a collection of Evola’s essays on the subject of mountain climbing:

At certain existential peaks, just as heat is transformed into light, life becomes free of itself; not in the sense of the death of individuality or some kind of mystical shipwreck, but in the sense of a transcendent affirmation of life, in which anxiety, endless craving, yearning and worrying, the quest for religious faith, human supports and goals, all give way to a dominating state of calm. There is something greater than life, within life itself, and not outside of it. This heroic experience is valuable and good in itself, whereas ordinary life is only driven by interests, external things and human conventions.45

According to Evola the human condition cannot and should not be embraced, but rather overcome. The cure does not consist in more money, more education, or moral uprightness, but in a radical and consistent commitment to pursue spiritual liberation. The past offers several examples of the distinction between an “ordinary” life and a “differentiated” life. The ancient Greeks referred to ordinary, material, physical life by the term bios, and used the term zoe to describe spiritual life. Buddhist and Hindu scriptures drew a distinction between samsara, or the life of needs, cravings, passions, and desires, and nirvana, a state, condition or extinction of suffering (dukka). Christian scriptures distinguish between the “life according to the flesh” and the “life according to the Spirit.” The Stoics distinguish between a “life according to nature” and a life dominated by passions. Heidegger distinguished between authentic and inauthentic life.

Kierkegaard talked about the aesthetic life and the ethical life. Zoroastrians distinguished between Good and Evil. The Essenes divided mankind into two groups: the followers of the Truth and the followers of the Lie.

The authors who first introduced Evola to the notions of self-sufficiency and of the “absolute individual” (an ideal, unattainable state) were Nietzsche and Carlo Michelstaedter. The latter was a twenty-three year old Jewish-Italian student who committed suicide in 1910, the day after completing his doctoral dissertation, which was first published in 1913 with the title La persuasione e la retorica (Persuasion and rhetoric).46 In his thesis, Michelstaedter claims that the human condition is dominated by remorse, melancholy, boredom, fear, anger, and suffering. Man’s actions reveal that he is a passive being. Because he attributes value to things, man is also distracted by them or by their pursuit. Thus man seeks outside himself a stable reference point, but fails to find it, remaining the unfortunate prisoner of his illusory individuality. The two possible ways to live the human condition, according to Michelstaedter, are the way of Persuasion and the way of Rhetoric. Persuasion is an unachievable goal. It consists in achieving possession of oneself totally and unconditionally, and in no longer needing anything else. This amounts to having life in one’s self. In Michelstaedter’s words:

The way of Persuasion, unlike a bus route, does not have signs that can be read, studied and communicated to others. However, we all have within ourselves the need to find that; we all must blaze our own trail because each one of us is alone and cannot expect any help from the outside. The way of Persuasion has only this stipulation: do not settle for what has been given you.47

On the contrary, the way of Rhetoric designates the palliatives or substitutes that man adopts in lieu of an authentic Persuasion. According to Evola, the path of Rhetoric is followed by “those who spurn an actual self-possession, leaning on other things, seeking other people, trusting in others to deliver them, according to a dark necessity and a ceaseless and indefinite yearning.”48 As Nietzsche wrote:

You crowd together with your neighbors and have beautiful words for it. But I tell you: Your love of your neighbor is your bad love of yourselves. You flee to your neighbor away from yourselves and would like to make a virtue of it: but I see through your selflessness. . . . I wish rather that you could not endure to be with any kind of neighbor or with your neighbor’s neighbor; then you would have to create your friend and his overflowing heart of yourselves.49

The goal of autarchy appears throughout Evola’s works. In his quest for this privileged condition, he expounded the paths blazed by various movements in the past, such as Tantrism, Buddhism, Mithraism, and Hermeticism.

In the early 1920s, Decio Calvari, president of the Italian Independent Theosophical League, introduced Evola to the study of Tantrism. Soon Evola began a correspondence with the learned British orientalist and divulger of Tantrism, Sir John Woodroffe (who also wrote with the pseudonym of “Arthur Avalon”), whose works and translations of Tantric texts he amply utilized. While René Guénon celebrated Vedanta as the quintessence of Hindu wisdom in his L’homme et son devenir selon le Vedanta (Man and his becoming according to the Vedanta) (1925), upholding the primacy of contemplation or of knowledge over action, Evola adopted a different perspective . Rejecting the view that spiritual authority is worthier than royal power, Evola wrote L’uomo come potenza (Man as power) in 1925. In the third revised edition (1949), the title was changed to Lo yoga della potenza (The yoga of power).50 This book represents a link between his philosophical works and the rest of his literary production, which focuses on Traditional concerns.

The thesis of The Yoga of Power is that the spiritual and social conditions that characterize the Kali-yuga greatly decrease the effectiveness of purely intellectual, contemplative, and ritual paths. In this age of decadence, the only way open to those who seek the “great liberation” is one of resolute action.51 Tantrism defined itself as a system based on practice, in which hatha-yoga and kundalini-yoga constitute the psychological and mental training of the followers of Tantrism in their quest for liberation. While criticizing an old Western prejudice according to which Oriental spiritualities are characterized by an escapist attitude (as opposed to those of the West, which allegedly promote vitalism, activism, and the will to power), Evola reaffirmed his belief in the primacy of action by outlining the path followed in Tantrism. Several decades later, a renowned member of the French Academy, Marguerite Yourcenar, paid homage to The Yoga of Power. She wrote of “the immense benefit that a receptive reader may gain from an exposition such as Evola’s,”52 and concluded that “the study of The Yoga of Power is particularly beneficial in a time in which every form of discipline is naively discredited.”53

But Evola’s interest was not confined to yoga. In 1943 he wrote The Doctrine of the Awakening, dealing with the teachings of early Buddhism. He regarded Buddha’s original message as an Aryan ascetic path meant for spiritual “warriors” seeking liberation from the conditioned world. In this book he emphasized the anti-theistic and anti-monistic insights of Buddha. Buddha taught that devotion to this or that god or goddess, ritualism, and study of the Vedas were not conducive to enlightenment, nor was experience of the identity of one’s soul with the “cosmic All” named Brahman, since, according to Buddha, both “soul” and “Brahman” are figments of our deluded minds.

In The Doctrine of the Awakening Evola meticulously outlines the four “jhanas,” or meditative stages, that are experienced by a serious practitioner on the path leading to nirvana. Most of the sources Evola drew from are Italian and German translations of the Sutta Pitaka, that part of the ancient Pali canon of Buddhist scriptures in which Buddha’s discourses are recorded. While extolling the purity and faithfulness of early Buddhism to Buddha’s message, Evola characterized Mahayana Buddhism as a later deviation and corruption of Buddha’s teachings, though he celebrated Zen54 and the doctrine of emptiness (sunyata) as Mahayana’s greatest achievements. In The Doctrine of the Awakening Evola extols the figure of the ahrat, one who has attained enlightenment. Such a person is free from the cycle of rebirth, having successfully overcome samsaric existence. The ahrat’s achievement, according to Evola, can be compared to that of the jivan-mukti of Tantrism, of the Mithraic initiate, of the Gnostic sage, and of the Taoist “immortal.”

This text was one of Evola’s finest. Partly as a result of reading it, two British members of the OSS became Buddhist monks. The first was H. G. Musson, who also translated Evola’s book from Italian into English. The second was Osbert Moore, who became a distinguished scholar of Pali, translating a number of Buddhist texts into English. On a personal note, I would like to add that Evola’s Doctrine of Awakening sparked my interest in Buddhism, leading me to read the Sutta Pitaka, to seek the company of Theravada monks, and to practice meditation.

In The Metaphysics of Sex (1958) Evola took issue with three views of human sexuality. The first is naturalism. According to naturalism the erotic life is conceived as an extension of animal instincts, or merely as a means to perpetuate the species. This view has recently been advocated by the anthropologist Desmond Morris, both in his books and in his documentary The Human Animal. The second view Evola called “bourgeois love”: it is characterized by respectability and sanctified by marriage. The most important features of this type of sexuality are mutual commitment, love, feelings. The third view of sex is hedonism. Following this view, people seek pleasure as an end in itself. This type of sexuality is hopelessly closed to transcendent possibilities intrinsic to sexual intercourse, and thus not worthy of being pursued. Evola then went on to explain how sexual intercourse can become a path leading to spiritual achievements.

Apoliteia

In 1988 a passionate champion of free speech and democracy, the journalist and author I. F. Stone, wrote a provocative book entitled The Trial of Socrates. In his book Stone argued that Socrates, contrary to what Xenophon and Plato claimed in their accounts of the life of their beloved teacher, was not unjustly put to death by a corrupt and evil democratic regime. According to Stone, Socrates was guilty of several questionable attitudes that eventually brought about his own downfall.

First, Socrates personally refrained from, and discouraged others from pursuing, political involvement, in order to cultivate the “perfection of the soul.” Stone finds this attitude reprehensible, since in a city all citizens have duties as well as rights. By failing to live up to his civic responsibilities, Socrates was guilty of “civic bankruptcy,” especially during the dictatorship of the Thirty. At that time, instead of joining the opposition, Socrates maintained a passive attitude: “The most talkative man in Athens fell silent when his voice was most needed.”55

Next, Socrates idealized Sparta, had aristocratic and pro-monarchical views, and despised Athenian democracy, spending a great deal of time in denigrating the common man. Finally, Socrates might have been acquitted if only he had not antagonized his jury with his amused condescension and invoked the principle of free speech instead.

Evola resembles Socrates in the attitudes toward politics described by Stone. Evola too professed “apoliteia.”56 He discouraged people from passionate involvement in politics. He was never a member of a political party, refraining even from joining the Fascist party during its years in power. Because of that he was turned down when he tried to enlist in the army at the outbreak of the World War II, although he had volunteered to serve on the front. He also discouraged participation in the “agoric life.” The ancient agora, or public square, was the place where free Athenians gathered to discuss politics, strike business deals, and cultivate social relationships. As Buddha said:

Indeed Ananda, it is not possible that a bikkhu [monk] who delights in company, who delights in society will ever enter upon and abide in either the deliverance of the mind that is temporary and delectable or in the deliverance of the mind that is perpetual and unshakeable. But it can be expected that when a bikkhu lives alone, withdrawn from society, he will enter upon and abide in the deliverance of mind that is temporal and delectable or in the deliverance of mind that is perpetual and unshakeable . . . . 57

Like Socrates, Evola celebrated the civic values, the spiritual and political achievements, and the metaphysical worth of ancient monarchies, warrior aristocracies, and traditional, non-democratic civilizations. He had nothing but contempt for the ignorance of ordinary people, for the rebellious masses, for the insignificant common man.

Finally, like Socrates, Evola never appealed to such democratic values as “human rights,” “freedom of speech,” and “equality,” and was “sentenced” to what the Germans call “death by silence.” In other words, he was relegated to academic oblivion.

Evola’s rejection of involvement in the socio-political arena must also be attributed to his philosophy of inequality. Norberto Bobbio, an Italian senator and professor emeritus of the philosophy department of the University of Turin, has written a small book entitled Right and Left: The Significance of a Political Distinction.58 In it Bobbio, a committed leftist intellectual, attempts to identify the key element that differentiates the political Right from the Left (a dyad rendered in the non-ideological American political arena by the dichotomy “conservatives and liberal,” or “mainstream and extremist”). After discussing several objections to the contemporary relevance of the Right-Left dyad following the decline and fall of the major political ideologies, Bobbio concludes that the juxtaposition of Right and Left is still a legitimate and viable one, though one day it will run its course, like other famous dyads of the past: “patricians and plebeians” in ancient Rome, “Guelphs and Ghibellines” during the Middle Ages, and “Crown and Parliament” in seventeenth century England.

At the end of his book Bobbio suggests that, “the main criterion to distinguish between Right and Left is the different attitude they have toward the ideal of equality.”59

Thus, according to Bobbio, the views of Right and Left on “liberty” and “brotherhood” (the other two values in the French revolutionary trio) are not as discordant as their positions on equality. Bobbio explains:

We may properly call “egalitarians” those who, while being aware that human beings are both equal and unequal, give more relevance, when judging them and recognizing their rights and duties, to that which makes them equal rather than to what makes them un-equal; and “inegalitarians,” those who, starting from the same premise, give more importance to what makes them unequal rather than to what makes them equal.60

Evola, as a representative of the European Right, may be regarded as one of the leading antiegalitarian philosophers of the twentieth century. Evola’s arguments transcend the age-old debate between those who claim that class, racial, educational, and gender differences between people are due to society’s structural injustices, and those who, on the other hand, believe that these differences are genetic. According to Evola there are spiritual and ontological reasons that account for differences in people’s lot in life. In Evola’s writings the social dichotomy is between initiates and “higher beings” on the one hand, and hoi polloi on the other.

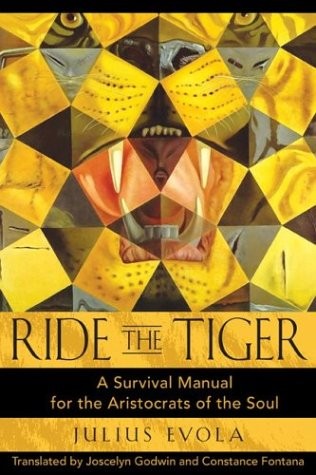

The two works that best express Evola’s apoliteia are Men among Ruins (1953) and Riding the Tiger (1961). In the former he expounds his views on the “organic” State, lamenting the emerging primacy of economics over politics in post-war Europe and America. Evola wrote this book to supply a point of reference for those who, having survived the war, did not hesitate to regard themselves as “reactionaries” deeply hostile to the emerging subversive intellectual and political forces that were re-shaping Europe:

Again, we can see that the various facets of the contemporary social and political chaos are interrelated and that it is impossible to effectively contrast them other than by returning to the origins. To go back to the origins means, plain and simple, to reject everything that, in every domain, whether social, political and economic, is connected to the “immortal principles” of 1789 in the guise of libertarian, individualistic and egalitarian thought, and to oppose to it a hierarchical view. It is only in the context of such a view that the value and freedom of man as a person are not mere words or pretexts for a work of destruction and subversion.61

Evola encourages his readers to remain passive spectators in the ongoing process of Europe’s reconstruction, and to seek their citizenship elsewhere:

The Idea, only the Idea must be our true homeland. It is not being born in the same country, speaking the same language or belonging to the same racial stock that matters; rather, sharing the same Idea must be the factor that unites us and differentiates us from everybody else.62

In Riding the Tiger, Evola outlines intellectual and existential strategies for coping with the modern world without being affected by it. The title is borrowed from a Chinese saying, and it suggests that a way to prevent a tiger from devouring us is to jump on its back and ride it without being thrown off. Evola argued that lack of involvement in the political and social construction of the human polis on the part of the “differentiated man” can be accompanied by a sense of sympathy toward those who, in various ways, live on the fringe of society, rejecting its dogmas and conventions.

The “differentiated person” feels like an outsider in this society and feels no moral obligation toward society’s request that he joins what he regards as an absurd system. Such a person can understand not only those who live outside society’s parameters, but even those who are set against such (a) society, or better, this society.63

This is why, in his 1968 book L’arco e la clava (The bow and the club), Evola expressed some appreciation for the “beat generation” and the hippies, all the while arguing that they lacked a proper sense of transcendence as well as firm points of spiritual reference from which they could launch an effective inner, spiritual “revolt” against society.

Guido Stucco has an M.A. in Systematic Theology at Seaton Hall and a Ph.D. in Historical Theology at St. Louis University. He has translated five of Evola’s books into English.

End Notes

1. For a good introduction to this movement and its ideas, William Quinn, The Only Tradition, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1997.

2. The first of the Theosophical Society’s three declared objectives was to promote the brotherhood of all men, regardless of race, creed, nationality, and caste.

3. Tomislav Sunic, Against Democracy and Equality: The European New Right, New York: Peter Lang, 1991; Ian B. Warren’s interview with Alain de Benoist, “The European New Right: Defining and Defending Europe’s Heritage,” The Journal of Historical Review, Vol.13, no. 2, March-April 1994, pp. 28-37; and the special issue “The French New Right,” Telos, Winter 1993-Spring 1994.

4. Martin Lee, The Beast Reawakens, Boston: Little, Brown, 1997.

5. Walter Laqueur, Fascism: Past, Present, Future, New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, pp. 97-98. Despite his bad press in the U.S., Evola’s works have been favorably reviewed by Joscelyn Godwin, “Evola: Prophet against Modernity,” Gnosis Magazine, Summer 1996, pp. 64-65; and by Robin Waterfield, “Baron Julius Evola and the Hermetic Tradition,” Gnosis Magazine, Winter 1990, pp. 12-17.

6. The first to write about Evola in this country was Thomas Sheehan, in “Myth and Violence: The Fascism of Julius Evola and Alain de Benoist,” Social Research, Vol. 48, Spring 1981, pp. 45-73. See also Richard Drake, “Julius Evola and the Ideological Origins of the Radical Right in Contemporary Italy,” in Peter Merkl (ed.), Political Violence and Terror: Motifs and Motivations, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986, pp. 61-89; “Julius Evola, Radical Fascism, and the Lateran Accords,” The Catholic Historical Review, Vol. 74, 1988, pp. 403-19; and the chapter “The Children of the Sun,” in The Revolutionary Mystique and Terrorism in Contemporary Italy, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989, pp. 116-134.

7. Philip Rees, in his Biographical Dictionary of the Extreme Right since 1890, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991, devotes a meager page and a half to Evola, and shamelessly concludes, without adducing a shred of evidence, that “ Evolian-inspired violence result[ed] in the Bologna station bombing of 2 August 1980.” Gianfranco De Turris, president of the Julius Evola Foundation in Rome and one of the leading Evola scholars, suggested that, in Evola’s case, rather than “bad teacher” one ought to talk about “bad pupils.” See his Elogio e difesa di Julius Evola: il barone e i terroristi, Rome: Edizioni Mediterranee, 1997, in which he debunks the unfounded charge that Evola was responsible either directly or indirectly for acts of terrorism committed in Italy.

8. See for instance Sheehan’s convoluted article “Diventare Dio: Julius Evola and the Metaphysics of Fascism,” Stanford Italian Review, Vol. 6, 1986, pp. 279-92, in which he tries to demonstrate that Nietzsche and Evola mirror each other. Sheehan should have rather spoken of an overcoming of Nietzsche’s philosophy on the part of Evola. The latter rejected Nietzsche’s notion of “Eternal Recurrence” as “nothing more than a myth”; his vitalism, because closed to transcendence and hopelessly immanentist; his “Will to Power” because: “Power in itself is amorphous and meaningless if it lacks the foundation of a given being, of an inner direction, of an essential unity” (Julius Evola, Cavalcare la tigre [Riding the tiger], Milan: Vanni Scheiwiller, 1971, p. 49); and, finally, Nietzsche’s nihilism, which Evola denounced as a project that had been implemented half-way.

9. H.T. Hansen, a pseudonym adopted by T. Hakl, is an Austrian scholar who earned a law degree in 1970. He is a partner in the prestigious Swiss publishing house Ansata Verlag and one of the leading Evola scholars in German-speaking countries. Hakl has translated several works by Evola into German and supplied lengthy scholarly introductions to most of them.

10. See for instance the topics of a conference held in France on the occasion of the centenary of his birth: “Julius Evola 1898-1998: Eveil, destin et expériences de terres spirituelles,” on the web site http://perso.wanadoo.fr/collectif.ea/langues/anglais/acteesf.htm.

11. Marcello Veneziani, Julius Evola tra filosofia e tradizione, Rome: Ciarrapico Editore, 1984, p. 110.

12. This work has been translated into French and German. My translation of the first volume is scheduled to be published in December 2002 by Inner Traditions, with the title Introduction to Magic: Rituals and Practical Techniques for the Magus.

13. Marco Rossi, a leading Italian authority on Evola, wrote an article on Evola’s alleged antidemocratic anti-Fascism in Storia contemporanea, Vol. 20, 1989, pp. 5-42.

14. Julius Evola, Il cammino del cinabro, Milan: Vanni Scheiwiller, 1972 , p. 162.

15. Julius Evola, Etica aria, Arian ethics, Rome: Europa srl, 1987, p. 28.

16. When Evola and a few friends came to the realization that the war was lost for the Axis, they began to draft plans for the creation of a “Movement for the Rebirth of Italy.” This movement was supposed to organize a right-wing political party capable of stemming the post-war influence of the Left. Nothing came of it, though.

17. Julius Evola, Il Cammino del cinabro, p. 183.

18. Julius Evola, Etica aria, p. 24.

19. In the beginning of his autobiography Evola claimed that reading Nietzsche fostered his opposition to Christianity, a religion which never appealed to him. He felt theories of sin and redemption, divine love, and grace as “foreign” to his spirit.

20. Rebora was imprecisely quoting from memory a saying by Jesus found in John 7:37. The exact quote is “Let anyone who is thirsty come to me, and let the one who believes in me drink.” (Revised Standard Version.)

21. Julius Evola, Lettere di Julius Evola a Girolamo Comi, 1934-1962, Rome: Fondazione Julius Evola, 1987, p. 17. In 1922 Evola was on the brink of suicide. He had experimented with hallucinogenic drugs and was consumed by an intense desire for extinction. In a letter dated July 2, 1921, Evola wrote to his friend Tristan Tzara: “I am in such a state of inner exhaustion that even thinking and holding a pen requires an effort which I am not often capable of. I live in a state of atony and of immobile stupor, in which every activity and act of the will freeze. . . . Every action repulses me. I endure these feelings like a disease. Also, I am terrified at the thought of time ahead of me, which I do not know how to utilize. In all things I perceive a process of decomposition, as things collapse inwardly, turning into wind and sand.” Lettere di Julius Evola a Tristan Tzara, 1919-1923, Rome: Julius Evola Foundation, 1991, p. 40. Evola was able to overcome this crisis after reading the Italian translation of the Buddhist text Majjhima-Nikayo, the so-called “middle length discourses of the Buddha.” In one of his discourses Buddha taught the importance of detachment from one’s sensory perceptions and feelings, including one’s yearning for personal extinction.

22. For a brief account of their correspondence, see Julius Evola, René Guénon: A Teacher for Modern Times, trans. by Guido Stucco, Edmonds, WA: Holmes Publishing Group, 1994.

23. Joscelyn Godwin, Arktos: The Polar Myth in Science, Symbolism, and Nazi Survival, Grand Rapids, MI: Phanes Press, 1993, p. 61.

24. In two letters to Comi, Evola wrote: “From a spiritual point of view my situation doesn’t mean more to me than a flat tire on my car”; and: “The small matter of my legs’ condition has only put some limitations on some profane activities, while on the intellectual and spiritual planes I am still following the same path and upholding the same views,” Lettere a Comi, pp. 18, 27.

25. The Middle Length Sayings, vol. III, trans. by I.B. Horner, London: Pali Text Society, 1959, p. 278.

26. Julius Evola, Cavalcare la tigre, p. 175.

27. Yuri Stoyanov, The Hidden Tradition in Europe, New York: Penguin, 1994, p. 8.

28. The Latin word hostis means both “guest” and “enemy.” This is revealing of how ancient Romans regarded foreigners in general.

29. Julius Evola, Revolt against the Modern World, Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 1995, p. 6. The first part of the book deals with the concepts noted in the extract cited. The second part of the book deals with the modern world.

30. Ibid.

31. All of these works have been translated and published in English by Inner Traditions.

32. Mircea Eliade, , Exile’s Odyssey, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988, p. 152.

33. Julius Evola, The Yoga of Power, trans. by Guido Stucco, Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 1992.

34. Mircea Eliade, Journal III, 1970-78, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989, p. 161.

35. Julius Evola, Il cammino del cinabro, p. 139.

36. Ibid.

37. Eliade, Journal III,1970-78, p. 162.

38. Ibid., pp. 162-63.

39. Mircea Eliade, Exile’s Odyssey, pp. 152. See also Alain de Benoist and quote him at length.

40. Ibid. This criticism was reiterated by S. Nasr in an interview to the periodical Gnosis.

41. Mircea Eliade, Journey East, Journey West, San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1981-88, p. 204.

42. Eliade, Journey East, Journey West, p. 202.

43. Evola, Il cammino del cinabro, p. 12.

44. Epicurus, Letter to Menoeceus, p. 47.

45. Julius Evola, Meditations on the Peaks, trans. by Guido Stucco, Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 1998, p. 5.

46. Carlo Michelstaedter, La persuasione e la retorica, Milan: Adelphi Edizioni, 1990.

47. Ibid., p. 104.

48. Il cammino del cinabro, p. 46.

49. F. Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, trans. by R.J. Hollingdale, London: Penguin Books, 1969, p. 86.

50. Evola, The Yoga of Power, trans. by Guido Stucco, Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 1992.

51. Evola would probably have liked Jesus’ saying (Luke 16:16): “The law and the prophets lasted until John; but from then on the kingdom of God is proclaimed and everyone who enters does so with violence.”

52. Marguerite Yourcenar, Le temps, ce grand sculpteur, Paris: Gallimard, 1983, p. 201.

53. Ibid., p. 204.

54. Julius Evola, The Doctrine of Awakening, Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 1995.

55. I. F. Stone, The Trial of Socrates, New York: Doubleday, 1988, p. 146.

56. Julius Evola, Cavalcare la tigre, pp. 174-78.

57. Mahajjima Nikayo, p. 122.

58. Norberto Bobbio, Destra e sinistra: ragioni e significati di una distinzione politica, Rome: Donzelli Editore, 1994. This book has been published in English as Left and Right: The Significance of a Political Distinction, Cambridge, England: Polity Press, 1996.

59. Ibid., p. 80.

60. Ibid., p. 74.

61. Julius Evola, Gli uomini e le rovine, Rome: Edizioni Settimo Sigillo, 1990, p. 64.

62. Ibid., p. 41.

63. Julius Evola, Cavalcare la tigre, p. 179.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Guardini wurde als Sohn einer aus Südtirol stammenden Mutter und eines italienischen Geflügelgroßhändlers geboren. 1886 übersiedelte die Familie nach Mainz, wo Guardini das humanistische Gymnasium absolviert.

Guardini wurde als Sohn einer aus Südtirol stammenden Mutter und eines italienischen Geflügelgroßhändlers geboren. 1886 übersiedelte die Familie nach Mainz, wo Guardini das humanistische Gymnasium absolviert. Guardinis Denkstil war wesentlich künstlerisch bestimmt, weshalb er in den späten Jahren auch in der Münchener Akademie der Schönen Künste eine herausgehobene Wirkungsstätte finden sollte. In seiner Münchener Zeit wandte sich Guardinis Deutungskunst auch Phänomenen wie dem Film zu. Wenn er schon mit der Schrift Der Heiland 1935 eine profunde christliche Kritik der NS-Ideologie vorgelegt hatte, so konnte er daran 1950 mit der Untersuchung Der Heilsbringer anknüpfen, einer bahnbrechenden Studie für das Verständnis von totalitären Ideologien als Politische Religionen. Wenig bekannt ist Guardinis Bemühung um ein hegendes »Ethos der Macht«, das gegenüber den anonymen Mächten zur Geltung zu bringen sei, die seiner Diagnose gemäß immer deutlicher zutage treten, das aber auch die charismatische Macht und Herrschaft zu domestizieren weiß.

Guardinis Denkstil war wesentlich künstlerisch bestimmt, weshalb er in den späten Jahren auch in der Münchener Akademie der Schönen Künste eine herausgehobene Wirkungsstätte finden sollte. In seiner Münchener Zeit wandte sich Guardinis Deutungskunst auch Phänomenen wie dem Film zu. Wenn er schon mit der Schrift Der Heiland 1935 eine profunde christliche Kritik der NS-Ideologie vorgelegt hatte, so konnte er daran 1950 mit der Untersuchung Der Heilsbringer anknüpfen, einer bahnbrechenden Studie für das Verständnis von totalitären Ideologien als Politische Religionen. Wenig bekannt ist Guardinis Bemühung um ein hegendes »Ethos der Macht«, das gegenüber den anonymen Mächten zur Geltung zu bringen sei, die seiner Diagnose gemäß immer deutlicher zutage treten, das aber auch die charismatische Macht und Herrschaft zu domestizieren weiß.

sich zu bezeichnen angewohnt hat. Insbesondere sein sowohl wissenschaftlichen Ansprüchen wie allgemeinverständlicher Darstellung gerecht werdendes Buch „Preußen. Geschichte eines Staates“ (1) ist als geschichtliche Einführung bis heute unübertroffen. Eine von Schoeps veranstaltete Preußen-Anthologie „Das war Preußen. Zeugnisse der Jahrhunderte“ wurde im übrigen von Julius Evola ins Italienische übersetzt. (2)

sich zu bezeichnen angewohnt hat. Insbesondere sein sowohl wissenschaftlichen Ansprüchen wie allgemeinverständlicher Darstellung gerecht werdendes Buch „Preußen. Geschichte eines Staates“ (1) ist als geschichtliche Einführung bis heute unübertroffen. Eine von Schoeps veranstaltete Preußen-Anthologie „Das war Preußen. Zeugnisse der Jahrhunderte“ wurde im übrigen von Julius Evola ins Italienische übersetzt. (2)

In seinem Buch „Gottheit und Menschheit. Die großen Religionsstifter und ihre Lehren“ (Stuttgart: Steingrüben 1950) nimmt Schoeps auch zum Islam Stellung, es hat aber den Anschein, dies geschähe mehr der Vollständigkeit halber als von Interesse oder Kompetenz her. Schoeps reiht einige der Platitüden der Orientalistik über den unoriginellen, allzumenschlichen usw. Propheten des Islam aneinander und charakterisiert den Islam als in seinem Prädestitationsdenken und seiner Schicksalsgläubigkeit „calvinistisch“, was genauso sinnvoll ist, wie das Christentum – unter Ausblendung all seiner anderen Strömungen – als calvinistisch zu bezeichnen. Tatsächlich schreibt Schoeps auch von der entgegengesetzten „pantheistischen“ Strömung, die Einseitigkeit durch eine zweite ergänzend. Denn in Wirklichkeit ist Ibn Arabi als wichtigster Vertreter des esoterischen Islam genausowenig pantheistisch wie Shankara, Meister Eckart oder Lao-Tse, deren grundsätzliche Identität mit seiner „Mystik“ oder vielmehr Gnosis aufgezeigt werden kann. Auch das beklagte „allzumenschliche“ also anscheinend unethische Verhalten des Propheten muß hinterfragt werden, denn es beruht auf einigen späten Hadithen. Träte uns Muhammad als fehlerlose Idealgestalt entgegen, wären die Orientalisten sofort bei der Stelle, um den geschichtlichen Wahrheitsgehalt dieser Stellen in Zweifel zu ziehen. Tatsächlich sind diese Berichte über Fehler und unmoralisches Verhalten aber Hadithen – vorwiegend aus der „Hadithfabrik“ von

In seinem Buch „Gottheit und Menschheit. Die großen Religionsstifter und ihre Lehren“ (Stuttgart: Steingrüben 1950) nimmt Schoeps auch zum Islam Stellung, es hat aber den Anschein, dies geschähe mehr der Vollständigkeit halber als von Interesse oder Kompetenz her. Schoeps reiht einige der Platitüden der Orientalistik über den unoriginellen, allzumenschlichen usw. Propheten des Islam aneinander und charakterisiert den Islam als in seinem Prädestitationsdenken und seiner Schicksalsgläubigkeit „calvinistisch“, was genauso sinnvoll ist, wie das Christentum – unter Ausblendung all seiner anderen Strömungen – als calvinistisch zu bezeichnen. Tatsächlich schreibt Schoeps auch von der entgegengesetzten „pantheistischen“ Strömung, die Einseitigkeit durch eine zweite ergänzend. Denn in Wirklichkeit ist Ibn Arabi als wichtigster Vertreter des esoterischen Islam genausowenig pantheistisch wie Shankara, Meister Eckart oder Lao-Tse, deren grundsätzliche Identität mit seiner „Mystik“ oder vielmehr Gnosis aufgezeigt werden kann. Auch das beklagte „allzumenschliche“ also anscheinend unethische Verhalten des Propheten muß hinterfragt werden, denn es beruht auf einigen späten Hadithen. Träte uns Muhammad als fehlerlose Idealgestalt entgegen, wären die Orientalisten sofort bei der Stelle, um den geschichtlichen Wahrheitsgehalt dieser Stellen in Zweifel zu ziehen. Tatsächlich sind diese Berichte über Fehler und unmoralisches Verhalten aber Hadithen – vorwiegend aus der „Hadithfabrik“ von