Academics are instructing their students that Europeans don’t inhabit a continental homeland independently of Asia and Africa. Their history has to be seen in the context of “reciprocal connections” with the globe. “The exceptional interconnectedness of Afroeurasia [5] shaped the history of this world zone in profound ways.” The only thing that stands out about Europeans was the “windfall” profits they obtained from the Americas, the “lucky” presence of coal in England, and the blood-stained manner they went about creating a new form of international slavery [6] combined with “scientific [7]” racism. Only a handful of soon-to-retire admirers of the West [8] remain.

The Enlightenment, always viewed as a European phenomenon, and respected in academia for its call upon “humanity” to subject all authority to critical reflection, is now enduring a fundamental revision as a movement that was global in origins and character. This is the view expressed in a recent article, “Enlightenment in Global History: A Historiographical Critique,” authored by Sebastian Conrad, who holds the Chair of Modern History at Freie University, Berlin. This is not an isolated paper, but a “historiographical” assessment based on current trends in the global history of the Enlightenment. The article was published in The American Historical Review, the official publication of the American Historical Association [9], and since 1895 a preeminent journal for the historical profession in the United States.

Conrad calls upon historians to move “beyond the obsession” and the “European mythology” that the Enlightenment was original to Europe:

The assumption that the Enlightenment was a specifically European phenomenon remains one of the foundational premises of Western modernity. . . . The Enlightenment appears as an original and autonomous product of Europe, deeply embedded in the cultural traditions of the Occident. . . . This interpretation is no longer tenable.

Conrad’s “critique” is vaporous, absurd, and unscholarly; a demonstration of the irrational lengths otherwise intelligent Europeans will go in their efforts to promote egalitarianism and affirmative action on a global scale. It is important for defenders of the West to see with clear eyes the extremely weak scholarship standing behind the prestigious titles and “first class” journals of many professors today. Conrad’s claims could have been taken seriously only within an academic environment bordering on pathological wishful thinking. (He is grateful to nine established academic readers plus “the anonymous reviewers” working for the AHR). The intended goal of Conrad’s paper is not truth but the dissolution of Europe’s intellectual identity within a mishmash of intercultural connections.

It should be noted that Conrad is a product of his time. The ploy to rob Europeans of their heritage has been in the making for some decades. It is no longer an affair restricted to squabbling academics looking for promotion, but has become an established reality across every high school and college in the West. This can be partly ascertained from a reading of the 2011 AP World History Standard [10], as mandated by The College Board, which was created in 1900 to expand access to higher education, with a current membership of 5,900 of the world’s leading educational institutions. This Board is very clear in its mandate that the courses developed for advanced placement in world history (for students to pursue college level studies while in high school) should “allow students to make crucial connections . . . across geographical regions.” The overwhelming emphasis of the “curriculum framework” is on “interactions,” “connected hemispheres,” “exchange and communication networks,” “interconnection of the Eastern and Western hemispheres,” and so on. For all the seemingly neutral talk about regional connections, the salient feature of this mandate is on how developments inside Europe were necessarily shaped by developments occurring in neighboring regions or even the whole world. One rarely encounters an emphasis on how developments in Asia were determined by developments in Europe – unless, of course, they point to the destructive effects of European aggression.

Thus, the Board continually mandates the teaching of topics such as: how “the European colonization of the Americas led to the spread of diseases,” how “the introduction of European settlements practices in the Americas often affected the physical environment through deforestation and soil depletion,” how “the creation of European empires in the Americas quickly fostered a new Atlantic trade system that included the trans-Atlantic slave trade,” and so on. The curriculum is thoroughly Marxist in its accent on class relations, coerced labor, “modes of production,” economic change, imperialism, gender, race relations, demographic changes, and rebellions. Europe’s contribution to painting, architecture, history writing, philosophy and science is never highlighted except when they can be interpreted as “ideologies” of the ruling (European) classes. It is not that the curriculum ignores the obvious formation of non-Western empires, but the weight is always on how, for example, the rise of “new racial ideologies, especially Social Darwinism, facilitated and justified imperialism.” Even the overwhelming reality of Europe’s contribution to science and technology in the nineteenth and twentieth century is framed as a global phenomenon in which all the regions were equal participants.[2]

A similar curriculum can be found across all the Social Sciences and Humanities in Western academia. This has been well-documented by various organizations [11] and publications. Suffice it to add that this globalist curriculum has long been promoted through countless university programs, organizations and journals, including the World History Association [12] (1982), the Journal of World History [13] (1990), the online journal World History Connected [14] (2003), and the H-World network [15]. Every single world history textbook, as far as I know, written in the last three decades or so, views Europe as an interconnected region with no special identity.[3]

Meanwhile, the Western Civilization history course, virtually a standard curriculum offering 30 years ago, disappeared from American colleges; today, only two percent [16] of colleges offer western civilization as a course requirement. No wonder the authors of recent Western Civ texts, pleading for survival, have been adopting a globalist approach; Brian Levack et al. thus writes in The West, Encounters & Transformations (2007): “we examine the West as a product of a series of cultural encounters both outside the West and within it” (xxx). They claim that one of the prominent religious features of the West was Islam. Clifford Backman, in his just released textbook, The Cultures of the West (2013), traces the origins of the West to Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Israel; and then goes on to tell students that his book is different from previous texts in treating Islam as “essentially a Western religion” and examining “jointly” the history of Europe and the Middle Eastern world (xxii).[4]

Conrad’s article came out of this background. His article seeks to show that recent research has proven false the “standard” Eurocentric interpretation of the Enlightenment. Conrad views this standard interpretation as the “master” narrative today, which continues to exist in the face of mounting evidence against it. It is true that the Enlightenment is still viewed as uniquely European by a number of well-respected scholars such as Margaret Jacob, Gertrude Himmelfarb, and Roy Porter. It is, actually, the most-often referred Western legacy used by right wing liberals (or neoconservatives) against the multicultural emphasis on the equality of cultures. These days, defending the West has come down to defending the “universal” values of the Enlightenment – gender equality, freedom of thought, and individual rights – against the “intolerant” particularism of other cultures. The late Christopher Hitchens, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Niall Ferguson, Pascal Bruckner [17] are some of the most notorious advocates of these values as universal norms that represent all human aspirations. The immigration of non-Europeans in the West poses no menace to them as long as they are transformed into happy consuming liberals. I have no interest celebrating the West from this cosmopolitan standpoint. It is commonly believe (including by members of the New Right) that the global interpretation Conrad delineates against a European-centered Enlightenment is itself rooted in the philosophes exaltation of “mankind.” Conrad knows this; in the last two paragraphs he justifies his postmodern reading of history by arguing that the Enlightenment “language of universal claim and worldwide validity” requires that its origins not be “restricted” to Europe. The Enlightenment, if it is to fulfill its universal promises, must be seen as the actual child of peoples across the world.

This is the more reason why Conrad’s arguments must be exposed, not only are they historically false, but they provide us with an opportunity to suggest (and argue further in a future paper) that the values of the Enlightenment are peculiarly European, rooted in this continent’s history, and not universally true and applicable to humanity. These values, for one, are inconsistent with Conrad’s style of research. Honest reflection based on reason and open inquiry shows that the Enlightenment was exclusively European. The great thinkers of the Enlightenment were aristocratic representatives of their people with a sense of rooted history and lineage. They did not believe (except for a rare few) that all the peoples of the earth were members of a race-less humanity in equal possession of reason. When they wrote of “mankind” they meant “European-kind.” When they wrote about equality they meant that Europeans have an innate a priori capacity to reason. When they said that “only a true cosmopolitan can be a good citizen,” they meant that European nationals should enlarge their focus and consider Europe “as a great republic.”

What concerns Conrad, however; and what will be the focus of this essay, is the promotion of a history in which the diverse cultures of the world can be seen as equal participants in the making of the Enlightenment. Conrad wants to carry to its logical conclusion the allegedly “universal” ideals of the Enlightenment, hoping to persuade Westerners that the equality and the brotherhood of mankind require the promotion of a Global Enlightenment.

Conrad blunders right from the opening when he references Toby Huff’s book, Intellectual Curiosity and the Scientific Revolution, as an example of the “no longer tenable” “standard reading” of the Enlightenment. First, this book is about the uniquely “modern scientific mentality” witnessed in seventeenth century Europe, not about the eighteenth century Enlightenment. It is also a study written, as the subtitle says, from “a Global Perspective.” Rather than brushing off this book in one sentence, Conrad should have addressed its main argument, published in 2010 and based on the latest research, showing that European efforts to encourage interest in the telescope in China, the Ottoman Empire, and Mughal India “did not bear much fruit.” “The telescope that set Europeans on fire with enthusiasm and curiosity, failed to ignite the same spark elsewhere. That led to a great divergence that was to last all the way to the end of the twentieth century” (5). The diffusion of the microscope met the same lack of curiosity. Why would Asia experience an Enlightenment culture together with Europe if it only started to embrace modern science with advanced research centres in the twentieth century? This simple question does not cross Conrad’s mind; he merely cites an innocuous sentence from Huff’s book which contains the word “Enlightenment” and then, without challenging Huff’s argument, concludes that “this interpretation is no longer tenable.”

Conrad then repeats phrases to the effect that the Enlightenment needs to be seen originally as “the work of historical actors around the world.” But as he cannot come up with a single Enlightenment thinker from the eighteenth century outside Europe, he immediately introduces postmodernist lingo about “how malleable the concept” of Enlightenment was from its inception, from which point he calls for a more flexible and inclusive definition, so that he can designate as part of the Enlightenment any name or idea he encounters in the world which carries some semblance of learning. He also calls for an extension of the period of Enlightenment beyond the eighteenth century all the way into the twentieth century. The earlier “narrow definitions of the term” must be replaced by open-minded and tolerant definitions which reflect the “ambivalences and the multiplicity of Enlightenment views” across the world.

From this vantage point, he attacks the “fixed” standard view of the Enlightenment. Early on, besides Huff’s book, Conrad footnotes Peter Gay’s The Enlightenment: An Interpretation, 2 vols. (1966-1969), Dorinda Outram’s, The Enlightenment (1995), Hugh Trevor-Roper’s, History and the Enlightenment (2010), as well as The Blackwell Companion to the Enlightenment (1992). Of these, I would say that Gay is the only author who can be said to have offered a synthesis that came to be widely held, but only from about the mid-60s to the mid-70s. In the first page of his book, Gay distinctly states that “the Enlightenment was united on a vastly ambitious program, a program of secularism, humanity, cosmopolitanism, and freedom” (1966: 3). In the case of Outram’s book, it is quite odd why Conrad would include it as a standard account since the back cover alone says it will view the Enlightenment “as a global phenomenon” characterized by contradictory trends. The book’s focus is on the role of coffee houses, religion, science, gender, and government from a cross-cultural perspective. In fact, a few footnotes later, Conrad cites this same book as part of new research pointing to the “heterogeneity” and “fragmented” character of the Enlightenment. However, the book makes not claims that the Enlightenment originated in multiple places in the world, and this is clearly the reason Conrad has labeled it as part of the “standard” view.

The truth is that Conrad has no sources to back his claim that there is currently a “dominant” and uniform view. Gay, Outram, Trevor-Roper, [5] including other sources he cites later (to be addressed below), are not part of a dominant view, but evince instead what Outram noticed in her book (first published in 1995): “the Enlightenment has been interpreted in many different ways” (8). This is why Conrad soon admits that “at present, only a small – if vociferous – minority of historians maintain the unity of the Enlightenment project.” Since Gay died in 2006, Conrad then comes up with two names, Jonathan Israel and John Robertson, as scholars who apparently hold today a unified view – yet, he then concedes, in a footnote, that these two authors have “a very different Enlightenment view: for Israel the ‘real’ Enlightenment is over by the 1740s, while for Robertson it only begins then.” In other words, on the question of timing, they have diametrically different views.

“Historiographical” studies are meant to clarify the state of the literature in a given historical subject, the trends, schools of thought, and competing interpretations. Conrad instead misreads, confounds and muddles up authors and books. The reason Conrad relies on Outram, and other authors, both as “dominant” and as pleasingly diverse, is that European scholars have been long recognizing the complexity and conflicting currents within the Enlightenment at the same time that they have continued to view it as “European” with certain common themes. We thus find Outram showing appreciation for the multiplicity and variety of views espoused during the Enlightenment while recognizing certain unifying themes such as the importance of reason, “non-traditional ways of defining and legitimating power,” natural law, and cosmopolitanism (140).

Conrad needs to use the proponents of Enlightenment heterogeneity to make his case that the historiography on this subject has been moving in the non-Western direction he wishes to nudge his readers into believing. But he knows that current experts on the European Enlightenment have not identified an Enlightenment movement across the globe from the eighteenth to the twentieth century, so he must also designate them (if through insinuation) as members of a still dominant Eurocentric group.

In the end, the sources Conrad relies on to advance his globalist view are not experts of the European Enlightenment but world historians (or actually, historians of India, China, or Middle East) determined to unseat Europe from its privileged intellectual position. Right after stating that there are hardly any current proponents of the dominant view, and that “most authors stress its plural and contested character,” Conrad reverts back to the claim that there is a standard view insomuch as most scholars still see the “birth of the Enlightenment” as “entirely and exclusively a European affair” which “only when it was fully fledged was it then diffused around the globe.” Here Conrad finally footnotes a number of books which can be said to exhibit an old fashion admiration for the Enlightenment as a movement characterized by certain common concerns, though he never explains why these books are mistaken in delimiting the Enlightenment to Europe. One thing is certain, these works go beyond Gay’s thesis. Gertrude Himmelfarb’s The Roads to Modernity: The British, French, and American Enlightenments (2004), challenges the older focus on France, its anti-clericalism, and radical rejection of traditional ways, by arguing that there were English as well as American “Enlightenments” that were quite moderate in their assessments of what human reason could do to improve the human condition, respectful of age-old customs, prejudices, and religious beliefs. John Headley’s The Europeanization of the World (2008) is not about the Enlightenment but the long Renaissance. Tzvetan Todorov’s In Defence of the Enlightenment (2009), with its argument against current “adversaries of the Enlightenment, obscurantism, arbitrary authority and fanaticism,” can be effectively used against Conrad’s own unfounded and capricious efforts. The same is true of Stephen Bronner’s Reclaiming the Enlightenment (2004), with its criticism of activists on the Left for spreading confusion and for attacking the Enlightenment as a form of cultural imperialism. These two books are a summons to the Left not to abandon the critical principles inherent in the Enlightenment. Robert Louden’s, The World We Want: How and Why the Ideals of the Enlightenment Still Eludes Us (2007), ascertains the degree to which the ideals of the Enlightenment have been successfully actualized in the world, both in Europe and outside, by examining the spread of education, tolerance, rule of law, free trade, international justice and democratic rights. His conclusion, as the title indicates, is that the Enlightenment remains more an ideal than a fulfilled program.

What Conrad might have asked of these works is: why they took for granted the universal validity of ideals rooted in the soils of particular European nations? Why they all ignored the intense interest Enlightenment thinkers showed in the division of humanity into races? Why did all these books, actually, abandon the Enlightenment call for uninhibited critical thinking by ignoring the vivid preoccupation of Enlightenment thinkers with the differences, racial and cultural, between the peoples of the earth? Why did they accept (without question) the notion that the same Kant [18] who observed that (i) “so fundamental is the difference between these two races of man [black and white] . . . as great in regard to mental capacities as in color,” was thinking (ii) about “mankind” rather than European kind when he defined the Enlightenment as “mankind’s exit from its self-incurred immaturity” through the courage to use [one’s own understanding] without the guidance of another”? Contrary to what defenders of the “emancipatory project of the Enlightenment” would have us believe, these observations were not incidental but reflections expressed in multiple publications and debated heavily; what were the differences among the peoples of different climes and regions? The general consensus among Enlightenment thinkers (in response to this question) was that animals as well as humans could be arranged in systematic hierarchies. Carl Linnaeus, for example, considered Europeans, Asians, American Indians, and Africans different varieties of humanity.[6]

However, my purpose here is to assess Conrad’s global approach, not to invalidate the generally accepted view of the Enlightenment as a project for “humanity.” It is the case that Conrad wants to universalize the Enlightenment even more by seeing it as a movement emerging in different regions of the earth. The implicit message is that the ideals of this movement can become actualize if only we imagine its origins to have been global. But since none of the experts will grant him this favor, as they continue to believe it “originated only in Europe,” notwithstanding the variety and tension they have detected within this European movement, Conrad decides to designate these scholars, past and present, as members of a “dominant” or “master” narrative. He plays around with the language of postcolonial critiques — the “brutal diffusion” of Western values, “highly asymmetrical relations of power,” “paternalistic civilizing mission” — the more to condemn the Enlightenment for its unfulfilled promises, and then criticizes these scholars, too, for taking “the Enlightenment’s European origins for granted.”

Who, then, are the “many authors” who have discovered that the Enlightenment was a worldwide creation? This is the motivating question behind Conrad’s historiographical essay. He writes: “in recent years, however, the European claim to originality, to exclusive authorship of the Enlightenment, has been called into question.” He starts with a number of sources which have challenged “the image of non-Western societies as stagnating and immobile”; publications by Peter Gran on Egypt’s eighteenth century “cultural revival,” by Mark Elvin on China’s eighteenth century “trend towards seeing fewer dragons and miracles, not unlike the disenchantment that began to spread across Europe during the Enlightenment,” and by Joel Mokyr’s observation that “some developments that we associate with Europe’s Enlightenment resemble events in China remarkably.”

This is pure chicanery. First, Gran’s book, Islamic Roots of Capitalism: Egypt, 1760–1840 (1979) has little to do with Enlightenment, and much to do with the bare beginnings of modernization in Egypt, that is, the spread of monetary relations, the gradual appearance of “modern products,” the adoption of European naval and military technology, the cultivation of a bit of modern science and medicine, the introduction (finally) of Aristotelian inductive and deductive login into Islamic jurisprudence. Gran’s thesis is simply that Egyptians were not “passive” assimilators of Western ways, but did so within the framework of Egyptian beliefs and institutions (178–188). Mokyr’s essay “The Great Synergy: The European Enlightenment as a Factor in Modern Economic Growth,” argues the exact opposite as the cited phrase by Conrad would have us believe. Mokyr’s contribution to the rise of the West debate has been precisely that there was an “Industrial” Enlightenment in the eighteenth century, which should be seen as the “missing link” between the seventeenth century world of Galileo, Bacon, and Newton and the nineteenth century world of steam engines and factories. He emphasizes the rise of numerous societies in England, the creation of information networks between engineers, natural philosophers, and businessmen, the opening of artillery schools, mining schools, informal scientific societies, numerous micro-inventions that turned scientific insights into successful business propositions, including a wide range of institutional changes that affected economic behavior, resource allocation, savings, and investment. There was no such Enlightenment in China where an industrial revolution only started in the mid-twentieth century.

His citation of Elvin’s observation that the Chinese were seeing fewer dragons in the eighteenth century cannot be taken seriously, and neither can vague phrases about “strange parallels” between widely separated areas of the world. Without much analysis but through constant repetition of globalist phrases, Conrad cites works by Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Arif Dirlik, Victor Lieberman, and Jack Goody. None of these works have anything to say about the Enlightenment. Some of them simply argue that capitalist development was occurring in Asia prior to European colonization. Conrad deliberately confounds the Enlightenment with capitalism, globalization, or modernization. He makes reference to a section in Jack Goody’s book, The Theft of History (2006: 122), with the subheading “Cultural similarities in east and west,” but this section is about (broad) similarities in family patterns, culinary practices, culture of flowers, and commodity exchanges in the major post-Bronze Age societies of Eurasia. There is not a single word about the Enlightenment! He cites Dirlik’s book, Global Modernity in the Age of Global Capitalism (2009), but this book is about globalization and not the Enlightenment.

Conrad’s historiographical study is a travesty intended to dissolve European specificity by way of sophomoric use of sources. He says that the Enlightenment was “the work of many authors in different parts of the world.” What he offers instead are incessant strings of similarly worded phrases in every paragraph about the “global context,” “the conditions of globality,” “cross-border circulations,” “structurally embedded in larger global contexts.” To be sure, these are required phrases in academic grant applications assessed by adjudicators who can’t distinguish enlightening thoughts from madrasa learning based on drill repetition and chanting.

A claim that there were similar Enlightenments around the world needs to come up with some authors and books comparable in their novelty and themes. The number of Enlightenment works during the eighteenth century numbered, roughly speaking, about one thousand five hundred.[7] Conrad does not come up with a single book from the rest of the world for the same period. Half way through his 20+ page paper he finally mentions a name from India, Tipu Sultan (1750–1799), the ruler of Mysore “who fashioned himself an enlightened monarch.” Conrad has very little to say about his thoughts. From Wikipedia one gets the impression that he was a reasonably good leader, who introduced a new calendar, new coinage, and seven new government departments, and made military innovations in the use of rocketry. But he was an imitator of the Europeans; as a young man he was instructed in military tactics by French officers in the employment of his father. This should be designated as dissemination, not invention.

Then Conrad mentions the slave revolt in Haiti led by Toussaint L’Ouverture, as an example of the “hybridization” of the Enlightenment. He says that Toussaint had been influenced by European critiques of colonialism, and that his “source of inspiration” also came from slaves who had “been born in Africa and came from diverse political, social and religious backgrounds.” Haitian slaves were presumably comparable to such enlightenment thinkers as Burke, Helvetius, D’Alembert, Galiani, Lessing, Burke, Gibbon, and Laplace. But no, the point is that Haitians made their own original contributions; they employed “religious practices such as voodoo [19] for the formation of revolutionary communities.” Strange parallels indeed!

He extends the period of the Enlightenment into the 1930s and 1940s hoping to find “vibrant and heated contestations of Enlightenment in the rest of the world.” He includes names from Japan, China, India, and the Ottoman Empire, but what all of them did was to simply introduce elements of the Enlightenment into their countries. He rehearses the view that these countries offered their own versions of modernity. Then he cites the following words from Liang Qichao, the most influential Chinese thinker at the beginning of the twentieth century, reflecting on his encounter with Western literature: “Books like I have never seen before dazzle my eyes. Ideas like I have never encountered before baffle my brain. It is like seeing the sun after being confined in a dark room.” Without noticing that these words refute his argument that Asians we co-participants of the Enlightenment, Conrad recklessly takes these words as proof that “the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century was not the intellectual monopoly of Europeans.” It does not occur to him that after the eighteenth century Europe moved beyond the Enlightenment exhibiting a dizzying display of intellectual, artistic, and scientific movements: romanticism, impressionism, surrealism, positivism, Marxism, existentialism, relativism, phenomenology, nationalism, fascism, feminism, realism, and countless other isms.

In the last paragraphs, as if aware that his argument was a charade, Conrad writes that “an assessment of the Enlightenment in global history should not be concerned with origins, either geographically or temporarily.” The study of origins, one of the central concerns of the historical profession, is thusly dismissed in one sentence. Perhaps he means that the “capitalist integration of the globe in an age of imperialism” precludes seeing any autonomous origins in any area of the world. World historians, apparently, have solved the problem of origins across all epochs and regions: it always the global context. But why it is that Europe almost always happens to be the progenitor of cultural novelties? One unfortunate result of this effort to see Enlightenments everywhere is the devaluation of the actual Enlightenment. If there were Enlightenment everywhere why should students pay any special attention to Europe’s great thinkers? It should come as no surprise that students are coming out with PhDs incapable of making distinctions between high and average achievements.

Alan Macfarlane, Professor Emeritus of King’s College, Cambridge, and longtime proponent of the idea that it was in western Europe between the thirteenth to eighteenth centuries that the “Nuclear Family based on Romantic Love, the Renaissance, Capitalism, the Scientific Revolution and the Industrial Revolution complex emerged,” has recently [20] observed that current efforts to explain Western uniqueness in global terms should be seen as responses to the rise of East Asia and its challenge to Western hegemony. The rise of the West, in light of this momentous rearrangement in geopolitical power, no longer seems so unusual, a “miracle,” but a phenomenon of short duration copied by other nations set to become the new hegemons. Macfarlane thinks it is important to reveal this background condition, and thereby disallow it from interfering with the actual historical record. Asia is rising today, but the West did so first in a very distinctive way.

This perspective strikes me as overtly academic and soft in its assessment of the underlying intentions driving the globalist historians. Macfarlane is a learned man who came of age in an England [21] long gone and suffering a huge ethnic alteration. The way this alteration was imposed, who and for what purposes, should be the background from which to evaluate this global perspective. The originality of the Enlightenment stands like an irritating thorn in the march towards equality and European nations inhabited by rootless cosmopolitan citizens without ethnic and nationalist roots. The achievements of Europeans must be erased from memory, replaced by a new history in which every racial group feels equally validated inside the Western world. In the meantime, the rise of Asians as Asians continues unabated and celebrated in Western academia.

Notes

1. “Capitalist Origins, the Advent of Modernity, and Coherent Explanation,” Canadian Journal of Sociology, 33, 1 (2008).

2. When I asked an American history teacher about The College Board, he replied: “The Board has a monopoly on the entire AP curriculum all across America and Canada and the rest of the world that buys into the program, i.e., ‘American schools’ anywhere and everywhere. And yes it is totally Marxist and it sickens me whenever the students have to regurgitate this totally one-sided perspective on the tests. Because the AP tests are based on the official curriculum, each AP World teacher must submit their syllabus to the board for approval. If the board does not approve, the school does not have the right to offer the test and the class is nullified. They have a tight grip on everything that goes on in the classroom, therefore. The trainings are something out of one of those university diversity trainings: anti-Western to the tilt. When they talk about European accomplishments, they do it tongue-in-cheek.”

3. For a thorough assessment of the pedagogical character of recent world history texts, which also covers world or universal historians from ancient times, see the 800-page survey by David Tamm, Universal History and the Telos of Human Progress (University of Antarctica Press, 2012). Tamm is an MA graduate aware that pursuing a PhD is virtually impossible if one rejects multiculturalism and mass immigration. He has founded his own virtual university in Antarctica with a publishing house.

A Wisconsin Policy Institute Research Report published in 2002, “Evaluating World History Texts in Wisconsin Public High Schools,” by Paul Kengor, made the following observations: “they avoid ethnocentrism, Euro-centrism, and so-called “Ameri-centrism;” “there are also multicultural excesses at the expense of the West;” “they include no section on the United States…Adams, Jefferson, Madison, Washington, Hamilton, and Lincoln are not mentioned even once;” “the most commonly named individuals in the texts are Mohammed, Gandhi, and Gorbachev;” “nearly all note the aggressive actions of Christianity in the distant past.” See: http://www.wpri.org/Reports/Volume15/Vol15no4.pdf [22]

4. Writing about Western Civ texts from a globalist approach has been building up since the 1990s; in this article published in 1998, Michael Doyle [23] asks teachers of Western Civ “to continue to incorporate a more inclusive approach to all cultures with which it [the West] came into contact.” “Certainly Western Civ students should read parts of the Qur’an and understand the attitudes that produced Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth.” He refers to Eric Hobsbawm’s [24] widely read books on European history as a model to be followed.

5. Designating Trevor-Roper’s History and the Enlightenment as a “standard” account seems out of place. Trevor-Roper died in 2003; and when his book was published, which consisted mainly of old essays, reviewers seemed more interested in Trevor-Roper the person than the authority on the Enlightenment. The New Republic [25] (March 2011) review barely touches is views on the Enlightenment, concentrating on Trevor-Roper’s life-time achievements as a historian and a man of letters. The Washington Post [26] (June 2010) correctly notes that Trevor-Roper was an “essayist by inclination,” interested in the details and idiosyncrasies of the characters he wrote about, without postulating a unified vision. The Blackwell Companion to the Enlightenment is a reference source encompassing many subjects from philosophy to art history, from science to music, with numerous topics (not demonstrative of a unifying/dominant view) ranging from absolutism to universities and witchcraft, publishing, language, art, music and the theater, including several hundred biographical entries of diverse personalities. Better examples of a dominant discourse would have been Ernest Cassirer’s The Philosophy of the Enlightenment or Norman Hampson’s, The Enlightenment. Mind you, Cassirer’s book was published in the 1930s and Hampson’s survey in 1968, and neither one is now seen as “dominant.”

6. Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze, ed., Race and the Enlightenment: A Reader (1997).

7. This is an approximate number I came up after counting the compilation of primary works cited in The Cambridge History of Eighteenth Century Philosophy, Volume II, Ed. Knud Haakonssen, (2006), pp. 1237–93.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

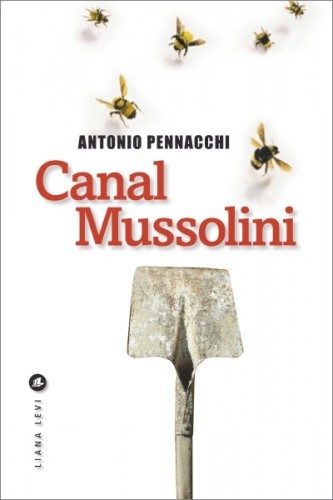

Canale Mussolini ist ein Epochen- und Familienroman, der – autobiographisch angereichert – davon erzählt, wie aus den Männern und Frauen einer norditalienischen, mittellosen Bauernsippe handfeste Faschisten werden: un-ideologische zwar, aber ist das nicht immer so, wenn es um die Masse unterhalb der weltanschaulich gefestigten Revolutionäre geht?

Canale Mussolini ist ein Epochen- und Familienroman, der – autobiographisch angereichert – davon erzählt, wie aus den Männern und Frauen einer norditalienischen, mittellosen Bauernsippe handfeste Faschisten werden: un-ideologische zwar, aber ist das nicht immer so, wenn es um die Masse unterhalb der weltanschaulich gefestigten Revolutionäre geht? Cofundador del Comité d’Action de Défense des Belges à l’Áfrique (CADBA), constituído en julio de 1960, inmediatamente después de las violaciones de Leopoldvlile y de Thysville, de las que fueron víctmas los belgas de Congo y cofundador del Mouvement d’Action Civique que sucedió al CADBA, el belga JeanThiriart, en diciembre de 1960, lanzó la organización Jeune Europe, que durante varios meses será el principal sostén logístico y base de retaguardia de la OAS-Metro.

Cofundador del Comité d’Action de Défense des Belges à l’Áfrique (CADBA), constituído en julio de 1960, inmediatamente después de las violaciones de Leopoldvlile y de Thysville, de las que fueron víctmas los belgas de Congo y cofundador del Mouvement d’Action Civique que sucedió al CADBA, el belga JeanThiriart, en diciembre de 1960, lanzó la organización Jeune Europe, que durante varios meses será el principal sostén logístico y base de retaguardia de la OAS-Metro.