mercredi, 09 septembre 2020

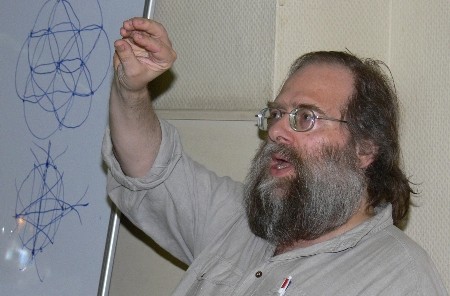

Kris Roman ontmoet Dr Koenraad Elst over Indië/China - deel 2 & deel 3

Время Говорить:

Kris Roman ontmoet Dr Koenraad Elst over Indië/China - deel 2 & deel 3

Deel 1:

12:45 Publié dans Actualité, Entretiens, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, entretien, géopolitique, politique internationale, koenraad elst, inde, chine, asie, affaires asiatiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 02 septembre 2020

Kris Roman ontmoet Dr Koenraad Elst over Indië/China

Время Говорить

Kris Roman ontmoet Dr Koenraad Elst over Indië/China

Nederlandse versie

03:07 Publié dans Actualité, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, tradition, inde, chine, koenraad elst, histoire |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 27 août 2020

Hinduism and the Culture Wars

12:14 Publié dans Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : hindoutva, hindouisme, tradition, traditionalisme, koenraad elst, inde, actualité |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Ram Swarup And Sita Ram Goel: Their Importance For Hindu Thought

Ram Swarup And Sita Ram Goel: Their Importance For Hindu Thought

Koenraad Elst

Voice Of India

12:07 Publié dans Philosophie, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : hindoutva, philosophie, philosophie politique, koenraad elst, inde, philosophie indienne, théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques, hindouisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 25 juin 2019

Le système des castes

Le système des castes

Koenraad Elst

Dans un débat inter-religions, la plupart des hindous peuvent facilement être mis sur la défensive avec un simple mot : caste. On peut s’attendre à ce que tout polémiste anti-hindou déclare que « le système des castes typiquement hindou est l’apartheid le plus cruel, imposé par les barbares envahisseurs Aryens blancs aux gentils indigènes à la peau sombre ». Voici une présentation plus équilibrée et plus historique de cette institution controversée.

Mérites du système des castes

Mérites du système des castes

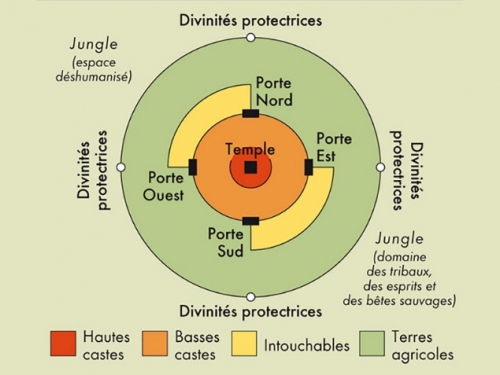

Le système des castes est souvent dépeint comme l’horreur absolue. L’inégalité innée est en effet inacceptable pour nous les modernes, mais cela n’empêche pas que ce système a aussi eu ses mérites. La caste est perçue comme une « forme d’exclusion », mais elle est avant tout une forme d’« appartenance », une structure naturelle de solidarité. Pour cette raison, les missionnaires chrétiens et musulmans trouvèrent très difficile d’attirer les hindous hors de leurs communautés. Parfois les castes furent collectivement converties à l’islam, et le pape Grégoire XV (1621-1623) décréta que les missionnaires pouvaient tolérer les distinctions de castes parmi les convertis au christianisme ; mais en gros, les castes restèrent un obstacle efficace à la destruction de l’hindouisme au moyen de la conversion. C’est pourquoi les missionnaires commencèrent à attaquer l’institution des castes et en particulier la caste des brahmanes. Cette propagande s’est épanouie en un anti-brahmanisme à part entière, l’équivalent indien de l’antisémitisme.

Chaque caste avait un grand espace d’autonomie, avec ses propres lois, droits et privilèges, et souvent ses propres temples. Les affaires inter-castes étaient résolues au conseil de village par consensus ; même la caste la plus basse avait un droit de veto. Cette autonomie des niveaux intermédiaires de la société est l’antithèse de la société totalitaire dans laquelle l’individu se trouve sans défense devant l’Etat tout-puissant. Cette structure décentralisée de la société civile et de la communauté religieuse hindoue a été cruciale pour la survie de l’hindouisme sous la domination musulmane. Alors que le bouddhisme fut balayé dès que ses monastères furent détruits, l’hindouisme se retira dans sa structure de castes et laissa passer la tempête.

Les castes fournirent aussi un cadre pour intégrer les communautés d’immigrants : juifs, zoroastriens et chrétiens syriaques. Ils ne furent pas seulement tolérés, mais assistés dans leurs efforts pour préserver leurs traditions distinctives.

Typiquement hindou ?

On prétend habituellement que la caste est une institution uniquement hindoue. Pourtant, les contre-exemples ne sont pas difficiles à trouver. En Europe et ailleurs, il y avait (ou il y a encore) une distinction hiérarchique entre nobles et roturiers, les nobles se mariant seulement entre eux. Beaucoup de sociétés tribales punissaient de mort le viol des règles d’endogamie.

Concernant les tribus indiennes, nous voyons les missionnaires chrétiens affirmer que les « membres des tribus ne sont pas des hindous parce qu’ils n’observent pas les castes ». En réalité, la littérature missionnaire elle-même est pleine de témoignages de pratiques de castes parmi les tribus. Un exemple spectaculaire est ce que les missions appellent « l’Erreur » : la tentative, en 1891, de faire manger ensemble des convertis des tribus de Chhotanagpur et des convertis d’autres tribus. Ce fut un désastre pour la mission. La plupart des indigènes renoncèrent au christianisme parce qu’ils choisirent de préserver le tabou des repas entre même tribu. Aussi énergiquement que le brahmane le plus hautain, ils refusaient de mélanger ce que Dieu avait séparé.

L’endogamie et l’exogamie sont observées par les sociétés tribales du monde entier. La question n’est donc pas de savoir pourquoi la société hindoue inventa ce système, mais comment elle put préserver ces identités tribales même après avoir dépassé le stade tribal de la civilisation. La réponse se trouve largement dans l’esprit intrinsèquement respectueux et conservateur de la culture védique en expansion, qui s’assura que chaque tribu pourrait préserver ses coutumes et traditions, y compris sa propre coutume d’endogamie tribale.

Description et histoire

Les colonisateurs portugais appliquèrent le terme caste, « lignage, espèce », à deux institutions hindoues différentes : le jati et le varna. L’unité effective du système des castes est le jati, l’unité de naissance, un groupe endogamique dans lequel vous êtes né, et à l’intérieur duquel vous vous marriez. En principe, vous pouvez manger seulement avec des membres du même groupe, mais les pressions de la vie moderne ont érodé cette règle. Les milliers de jatis sont subdivisés en clans exogames, les gotras. Cette double division remonte à la société tribale.

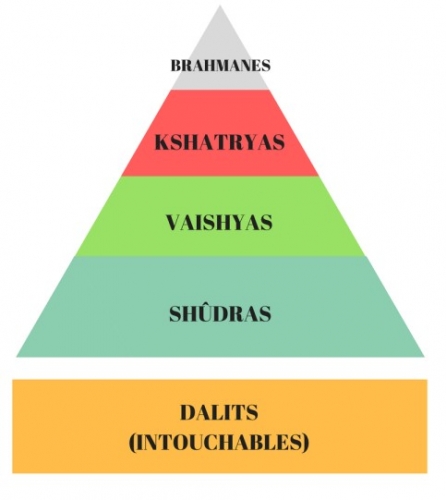

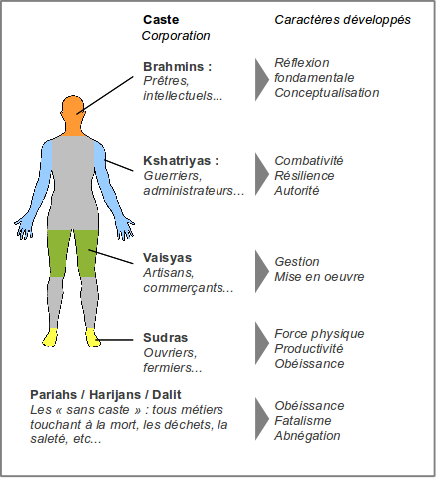

Par contre, le varna est la division fonctionnelle typique d’une société avancée : la civilisation de l’Indus/Saraswati, au troisième millénaire avant JC. La partie la plus récente du Rig-Veda décrit quatre classes : les brahmanes érudits nés de la bouche de Brahma, les kshatriyas guerriers nés de ses bras ; les entrepreneurs vaishyas nés de ses hanches et les travailleurs shudras nés de ses pieds. Tout le monde est un shudra par la naissance. Les garçons deviennent dwija, deux-fois nés, ou membres de l’un des trois varnas supérieurs en recevant le cordon sacré dans la cérémonie de l’upanayama.

Le système du varna se diffusa à partir de la région de Saraswati-Yamuna et s’établit fermement dans l’ensemble de l’Aryavarta (du Cachemire au Vidarbha, du Sind au Bihar). Il était le signe d’une culture supérieure plaçant le pays central aryen civilisé à l’écart des pays mleccha barbares environnants. Au Bengale et dans le Sud, le système était réduit à une distinction entre brahmanes et shudras. Le varna est une catégorie rituelle et ne correspond pas pleinement à un statut social ou économique effectif. Ainsi, la moitié des souverains princiers en Inde Britannique étaient des shudras et quelques-uns étaient des brahmanes, bien que ce fût une fonction kshatriya par excellence. Beaucoup de shudras sont riches, beaucoup de brahmanes sont pauvres.

Le Mahabharata définit ainsi les qualités du varna : « Celui en qui vous trouvez véracité, générosité, absence de haine, modestie, bonté et retenue, est un brahmane. Celui qui accomplit les devoirs d’un chevalier, étudie les écritures, se concentre sur l’acquisition et la distribution de richesses, est un kshatriya. Celui qui aime l’élevage, l’agriculture et l’argent, qui est honnête et bien versé dans les écritures, est un vaishya. Celui qui mange n’importe quoi, pratique n’importe quel métier, ignore les règles de pureté, et ne prend aucun intérêt aux écritures et aux règles de vie, est un shudra ». Plus le varna est élevé, plus les règles d’autodiscipline doivent être observées. C’est pourquoi un jati pouvait collectivement améliorer son statut en adoptant davantage de règles de conduite, par ex. le végétarisme.

Le second nom d’une personne indique habituellement son jati ou gotra. De plus, on peut utiliser les titres suivants de varna : Sharma (refuge, ou joie) indique un brahmane, Varma (armure) un kshatriya, Gupta (protégé) un vaishya et Das (serviteur) un shudra. Dans une seule famille, une personne peut s’appeler Gupta (varna), une autre Agrawal (jati), et encore une autre Garg (gotra). Un moine, en renonçant au monde, abandonne son nom en même temps que son identité de caste.

Intouchabilité

Au-dessous de la hiérarchie des castes se trouvent les Intouchables, ou harijan (littéralement « les enfants de Dieu »), ou dalits (« opprimés »), ou paraiah (formant une caste en Inde du Sud), ou Scheduled Castes [« castes répertoriées »]. Elles forment environ 16% de la population indienne, autant que les castes supérieures combinées.

L’intouchabilité a son origine dans la croyance que les esprits mauvais entourent la mort et les substances en décomposition. Les gens qui travaillaient avec les cadavres, les excréments ou les peaux d’animaux avaient une aura de danger et d’impureté, ils étaient donc maintenus à l’écart de la société normale et des enseignements et rituels sacrés. Cela prenait souvent des formes grotesques : ainsi, un intouchable devait annoncer sa proximité polluante avec une sonnette, comme un lépreux.

L’intouchabilité est inconnue dans les Védas, et donc répudiée par les réformateurs néo-védiques comme Dayanand Saraswati, Narayan Guru, Gandhiji [Gandhi] et Savarkar. En 1967, le Dr. Ambedkar, un dalit par la naissance et un critique acharné de l’injustice sociale dans l’hindouisme et dans l’islam, réalisa une conversion de masse au bouddhisme, en partie à cause de la supposition (non fondée historiquement) suivant laquelle le bouddhisme aurait été un mouvement anti-caste. La constitution de 1950 supprima l’intouchabilité et approuva des programmes de discrimination positive pour les Scheduled Castes et les Tribus. Dernièrement, le Vishva Hindu Parishad a réussi à faire entrer même les leaders religieux les plus traditionalistes dans la plate-forme anti-intouchabilité, pour qu’ils invitent des harijans dans des écoles védiques et qu’ils les forment à la prêtrise. Dans les villages, cependant, le harcèlement des dalits est encore un phénomène commun, occasionné moins par des questions de pureté rituelle que par des disputes pour la terre et le travail. Néanmoins, l’influence politique croissante des dalits accélère l’élimination de l’intouchabilité.

Conversions inter-castes

Dans le Mahabharata, Yuddhishthira affirme que le varna est défini par les qualités de la tête et du cœur, pas par la naissance. Krishna enseigne que le varna est défini par l’activité (le karma) et la qualité (le guna). Encore aujourd’hui, le débat n’est pas clos pour savoir dans quelle mesure la « qualité » de quelqu’un est déterminée par l’hérédité ou par l’influence environnementale. Et ainsi, alors que la vision héréditaire a été prédominante pendant longtemps, la conception non-héréditaire du varna a toujours été présente aussi, comme cela apparaît d’après la pratique de conversion inter-varnas. Le plus célèbre exemple est le combattant de la liberté au XVIIe siècle, Shivaji, un shudra à qui fut accordé un statut de kshatriya pour cadrer avec ses exploits guerriers. L’expansion géographique de la tradition védique fut réalisée par l’initiation à grande échelle des élites locales dans l’ordre des varnas. A partir de 1875, l’Arya Samaj a systématiquement administré le « rituel de purification » (shuddhi) aux convertis musulmans et chrétiens et aux hindous de basse caste, accomplissant leur dwija. Inversement, l’actuelle politique de discrimination positive a poussé les gens des castes supérieures à se faire accepter dans les Scheduled Castes favorisées.

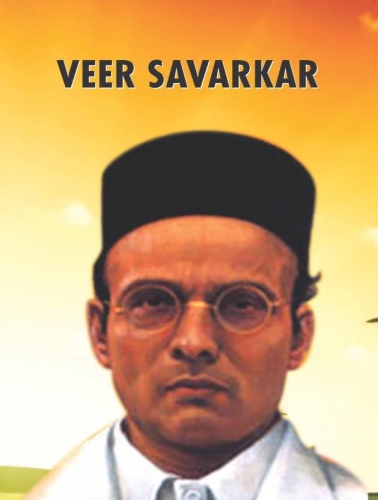

Veer Savarkar, l’idéologue du nationalisme hindou, prônait les mariages inter-castes pour unifier la nation hindoue même au niveau biologique. La plupart des hindous contemporains, bien qu’à présent généralement opposés à l’inégalité de caste, continuent à se marier dans leurs jatis respectives parce qu’ils ne voient pas de raison de les supprimer.

Veer Savarkar, l’idéologue du nationalisme hindou, prônait les mariages inter-castes pour unifier la nation hindoue même au niveau biologique. La plupart des hindous contemporains, bien qu’à présent généralement opposés à l’inégalité de caste, continuent à se marier dans leurs jatis respectives parce qu’ils ne voient pas de raison de les supprimer.

Théorie raciale des castes

Au XIXe siècle, les Occidentaux projetèrent la situation coloniale et les théories raciales les plus récentes [de l’époque] sur le système des castes : les castes supérieures étaient les envahisseurs blancs dominant les indigènes à la peau sombre. Cette vision périmée est toujours répétée ad nauseam par les auteurs anti-hindous : maintenant que « idolâtrie » a perdu de sa force comme terme injurieux, « racisme » est une innovation bienvenue pour diaboliser l’hindouisme. En réalité, l’Inde est la région où tous les types de couleur de peau se sont rencontrés et mélangés, et vous trouverez de nombreux brahmanes aussi noirs que Nelson Mandela. D’anciens héros « aryens » comme Rama, Krishna, Draupadi, Ravana (un brahmane) et un grand nombre de voyants védiques furent explicitement décrits comme ayant la peau sombre.

Mais varna ne signifie-t-il pas « couleur de peau » ? Le véritable sens de varna est « splendeur, couleur », d’où « qualité distinctive » ou « un segment d’un spectre ». Les quatre classes fonctionnelles constituent les « couleurs » dans le spectre de la société. Les couleurs symboliques sont attribuées aux varnas sur la base du schéma cosmologique des « trois qualités » (triguna) : le blanc est sattva (véridique), la qualité typique du brahmane ; le rouge est rajas (énergétique), pour le kshatriya ; le noir est tamas (inerte, solide), pour le shudra ; le jaune est attribué au vaishya, qui est défini par un mélange de qualités.

Finalement, la société des castes a été la société la plus stable dans l’histoire. Les communistes indiens avaient l’habitude de dire en ricanant que « l’Inde n’a jamais connu de révolution ». En effet, ce n’est pas une mince affaire.

Traduction du texte anglais publié sur : http://www.geocities.com/integral_tradition/

11:36 Publié dans Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : castes, traditions, hindouisme, inde, koenraad elst, koen elst |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 25 juin 2016

Nieuw-rechts voor de praktijk

Door: Koenraad Elst

Nieuw-rechts voor de praktijk

Nadat ik in 1992 onverwacht uitgenodigd was om me bij de redactie van het Nieuw-Rechtse tijdschrift TeKoS te vervoegen, vroeg ik me af waar ik nu in terecht gekomen was. Het was allemaal erg retro, met nieuwheidenen wier Indo-Europese theorievorming in het interbellum was blijven steken, traditionalisten die met de Franse islambekeerling René Guénon uit het interbellum dweepten, historici met hyperfocus op oorlog en repressie, en vooral een algemene fascinatie met de mij tot dan onbekende Conservatieve Revolutie, een gedachtenstroming uit de Weimar-republiek. En die situeerde zich, wat dacht u, in het interbellum. Artikels over dat onderwerp bleven ongelezen, of ik kreeg ze met veel moeite doorploegd. Uit die stal heb ik uiteindelijk alleen het Reisetagebuch eines Philosophen van graaf Hermann Keyserling gelezen, dat hoofdzakelijk over Aziatische beschavingen handelt.

Wat mij dan toch met dat milieu kon verzoenen, was, behalve de onmiskenbare toewijding van de redactieleden aan de conservatieve zaak, de originele invalshoek op ecologie door de zopas van ons heengegane Guy De Maertelaere, en de lucide commentaren op hedendaagse politieke kwesties vanuit Nieuw-Rechtse hoek. Zo signaleer ik de duidelijke pro-Europese opstelling van de redactie, destijds vanzelfsprekend maar vandaag een strijdpunt.

Nieuw Rechts

De Nouvelle Droite is een in Frankrijk ontstane stroming (°1968) rond Alain de Benoist, die ideologisch dieper wilde gaan dan de in de politiek actieve rechtse stromingen. Ze werd beschreven als een 'gramscisme van rechts': zoals de Italiaanse communist Antonio Gramsci rond 1930 het standpunt ontwikkelde dat een politieke revolutie maar kan mits de verwerving van de culturele hegemonie (door naoorlogs links met succes in de praktijk gebracht, zonder in een politieke revolutie uit te monden maar wel in 'bizarre en schadelijke sociale experimenten', p.13), zo stond de Nouvelle Droite een herovering van de cultuursfeer voor. Ze heeft echter politiek nooit enige potten gebroken en is in eigen land ook op het intellectuele forum marginaal gebleven; de beoogde herinname van het culturele domein werd een totale mislukking. Vandaag is de bejaarde duizendpoot de Benoist, door zijn vroegere medestanders verlaten, denkmeester van enkele interessante tijdschriften, maar verder dan lezenswaardige duiding reikt zijn invloed niet.

De eerste generatie van de Nouvelle Droite deed baanbrekend denkwerk, haar tweede ging van debat over in ruzies en splitsingen en loste op in irrelevantie, maar haar kleinkinderen blijken nu een verrassende opmars te doen. In het voormalige Sovjetblok heeft zij reeds enkele triomfen geoogst. In de heel verschillende omstandigheden van West-Europa, met zijn agressief opdringend multiculturalisme, blijkt zij nu toch door te breken.

Een jaar of wat geleden deed het boek Avondland en Identiteit van Sid Lukkassen (Aspekt, Soesterberg 2015) veel stof opwaaien. Het maakt de diagnose van de overheersende ideologie, het cultuurmarxisme, of wat zichzelf de 'kritische theorie' noemt, ontsproten aan de Frankfurter Schule. Verder trok het de aandacht met zijn uitgebreide ontleding van de effecten van deze culturele revolutie op de geslachtsrollen en de relatiemarkt. Dat leidde ertoe dat TeKoS twee heel verschillende besprekingen publiceerde, waarbij de vrouwelijke recensente heel wat mannelijke subjectiviteit in Lukkassens verhaal ontwaarde. Maar allen waren het eens over zijn uitstekende diagnose van, en weerstand tegen, het cultuurmarxisme. Hij dacht parallel met de Nouvelle Droite hoewel hij er zich niet uitdrukkelijk op beriep.

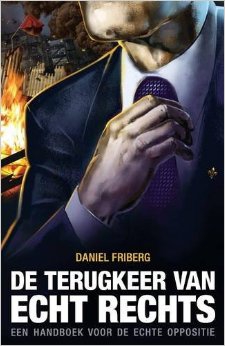

Zopas kreeg ik ter bespreking de Nederlandse vertaling aangeboden van het boekje van de Zweedse mijnbouwondernemer en oppositieleider Daniel Friberg: De Terugkeer van Echt Rechts. Een Handboek voor de Echte Oppositie (Arktos, London 2016). In zijn geval is het Nieuw-Rechtse gedachtengoed ontdekt en relevant geworden vanuit de praktijk, een heel andere setting dan de Parijse salons. Zweden was schijnbaar de slechtste plaats ter wereld voor een tegenbeweging tegen de opdringende multiculturele staatsideologie. Voor de beginnende Zweedse Democraten was het jarenlang een harde strijd. Hun enige kracht was de zekerheid dat zij gelijk hadden, dat zij een terugkeer naar de normaliteit nastreefden tegen de tegennatuurlijke utopieën van de almachtige cultuurmarxisten in.

Zopas kreeg ik ter bespreking de Nederlandse vertaling aangeboden van het boekje van de Zweedse mijnbouwondernemer en oppositieleider Daniel Friberg: De Terugkeer van Echt Rechts. Een Handboek voor de Echte Oppositie (Arktos, London 2016). In zijn geval is het Nieuw-Rechtse gedachtengoed ontdekt en relevant geworden vanuit de praktijk, een heel andere setting dan de Parijse salons. Zweden was schijnbaar de slechtste plaats ter wereld voor een tegenbeweging tegen de opdringende multiculturele staatsideologie. Voor de beginnende Zweedse Democraten was het jarenlang een harde strijd. Hun enige kracht was de zekerheid dat zij gelijk hadden, dat zij een terugkeer naar de normaliteit nastreefden tegen de tegennatuurlijke utopieën van de almachtige cultuurmarxisten in.

In 2005 kwam een kleine groep hoogstudenten in Göteborg bijeen om Nieuw-Rechtse denkers te lezen: 'Deze artikels openden onze ogen voor dit nieuwe intellectuele arsenaal van rechts', in het bijzonder voor de 'metapolitiek van rechts'. (p.10) Dat leidde tot de oprichting van de Nieuw-Rechtse denktank Motpol, 'tegenpool', op 10 juli 2006. Eerst sceptisch bejegend door links en door 'oud, impotent rechts', groeide het uit tot een gerespecteerd netwerk dat in heel Zweden seminaries organiseert en een degelijk online magazine uitgeeft. Friberg geeft blijk van groot vertrouwen in de toekomst en hij beschrijft de 'dalende relevantie' (p.43) van links, waarvan hij de nakende ondergang voorspelt.

Programma

Enkele concrete blikvangers uit Fribergs ideologische zelfprofilering. Tegen de grootmachten 'is een verenigd, onafhankelijk Europa noodzakelijk' met 'een gemeenschappelijk buitenlands beleid, een verenigd leger en een gemeenschappelijke wil om Europa's belangen globaal te verdedigen'. (p.14) In beperkte zin, enkel op deze terreinen, wil hij 'Imperium Europa, of een Europese federatie'. (p.25) Nationaal-populistische partijen als de PVV of het Front National zijn nogal eens tegen de Europese eenmaking in een overreactie tegen de antidemocratische en totalitaire uitspattingen van de EU.

In de buitenlandse politiek beveelt hij zelfbeheersing en omzichtigheid aan. Europa heeft een militaire poot nodig om geloofwaardig in het machtspolitieke spel te kunnen meespelen, maar niet om zich naar Amerikaans voorbeeld met andermans conflicten te moeien. Hij verzet zich tegen 'de fanatieke oorlogsstokers die, terwijl ze clichés uitgalmen over mensenrechten en democratie, miljoenen mensen doden over heel de wereld en tegelijkertijd dezelfde retoriek gebruiken om massa-immigratie vanuit de Derde Wereld naar Europa aan te moedigen.' (p.28)

In de buitenlandse politiek beveelt hij zelfbeheersing en omzichtigheid aan. Europa heeft een militaire poot nodig om geloofwaardig in het machtspolitieke spel te kunnen meespelen, maar niet om zich naar Amerikaans voorbeeld met andermans conflicten te moeien. Hij verzet zich tegen 'de fanatieke oorlogsstokers die, terwijl ze clichés uitgalmen over mensenrechten en democratie, miljoenen mensen doden over heel de wereld en tegelijkertijd dezelfde retoriek gebruiken om massa-immigratie vanuit de Derde Wereld naar Europa aan te moedigen.' (p.28)

Gehard door de praktijk, geeft Friberg raad voor de omgang met extreemlinkse haatgroepen zoals Searchlight en het Southern Poverty Law Center, op kleinere schaal vertaalbaar als ons Anti-Fascistisch Front. Die komt erop neer dat je hen niet méér belang moet geven dan ze verdienen, namelijk hoe langer hoe minder. Weiger elke medewerking wanneer ze je belasteren ('geen commentaar'), en maai de grond onder hun voeten weg door alternatieve netwerken en media uit te bouwen. Vóór het internet een democratisch circuit schiep, konden zij beschikken over de officiële media met hun monopolie, wier partijdigheid en leugens je machteloos moest ondergaan. Vandaag leven we in een nieuwe wereld waarin de greep van het cultuurmarxisme op het eerste gezicht machtiger is dan ooit, maar in feite steeds meer terrein moet prijsgeven.

Maar is er dan geen waakzaamheid nodig (de zich protsering antifa's noemende fichenbaktijgers heten ook watchdogs), tegen het geweldpotentieel van rechts? Niet bij deze stroming: 'Politiek geweld, hetzij georganiseerd of door individuen, kan geen enkele positieve rol spelen in de wedergeboorte van Europa. (...) Revolutionaire praatjes brengen enkel de mentaal onstabielen in beroering om gewelddaden te plegen die immoreel zijn en geen enkel tactisch nut hebben. We moeten deze daden overlaten aan extreemlinks en radicale islamisten, voor wie ze een tweede natuur zijn. (...) Onze methode is, nogmaals, de metapolitieke methode – de maatschappij geleidelijk veranderen in een richting die gunstig is voor onszelf, en belangrijker, voor de maatschappij in het algemeen.' (p.30-31)

Metapolitiek is diametraal tegengesteld aan de spontaneïstisch-gewelddadige methode van Anders Breivik, die we met een variatie op Lenin de 'de extreemrechtse stroming, de kinderziekte van het antimulticulturalisme' kunnen noemen. In zijn Manifest zegt Breivik zelf dat hij vroeger lid was van de Noorse immigratiekritische Vooruitgangspartij, maar dat hij niet meer in de binnenparlementaire werking gelooft en nu hoopt dat zijn misdaden zoveel mogelijk schade zullen toebrengen aan zijn vroegere vrienden. En inderdaad, de media hebben de Vooruitgangspartij volop in 'schuld door associatie' ondergedompeld, wat haar tijdelijk heeft doen achteruitgaan, zoals beoogd. Breivik-Antifa, zelfde strijd!

Een praktische raad betreft het domein dat Lukkassen al ruim verkend had: de uitdagingen van de betrekking tussen de geslachten en de paarvorming. 'Mannen en vrouwen hebben in het moderne Westen niets om trots op te zijn.' (p.45) Wanneer de Nouvelle Droite destijds het gelijkheidsdenken als probleem bij uitstek aanwees, verdacht ik haar ervan een bedekt pleidooi voor uitbuiting en dergelijke ongelijkheid te houden; maar het problematische van het gelijkheidsideaal wordt veel duidelijker wanneer je de schade ziet die het aan de geslachtsrelaties toegebracht heeft. Van quota om vrouwen in mannenberoepen binnen te loodsen beleefden we een crescendo naar 'genderstudies, een belachelijke wetenschap met als enige doel, de genderrollen af [te] breken'. Hij raadt de jongeren aan, niet te veel in het zoeken naar en beleven van relaties te investeren, tenzij dan om iets duurzaams uit te bouwen en uiteindelijk een gezin te stichten. Dat is minder stoer en opzichtig dan stereotiepe rechtse rakkers wensen, maar des te opbouwender voor het Europa van de toekomst.

Identiteit

Vertaler van het werk is Jens De Rycke. Uitgever John Morgan wijst in zijn voorwoord op het revolutionaire karakter van Echt Rechts, vooral ook in zijn oorspronkelijke betekenis: terugdraaien naar de begintoestand. Hij definieert die stroming als 'niet conservatief in de normale betekenis van het woord, aangezien [ze] niet de hedendaagse Europese beschaving tracht te behouden (...) maar de waarden en idealen te hernieuwen die voor de komst van het liberalisme als natuurlijk beschouwd werden.' (p.ix) In een tweede voorwoord prijst Joakim Andersen, redacteur van Motpol, nog eens de verdiensten van de auteur. Het boekje besluit met een verklaring van de relevante politieke termen en een nawoord.

Voor de goede orde herhaal ik even dat voor mijzelf 'identiteit' geen voorwerp van politieke actie kan zijn: identiteit is er gewoon en zorgt wel voor zichzelf. Zij is de toevallige resultante van het samenspel van die krachten waar het werkelijk om gaat. Wanneer de Kerk haar traditionele waarden verdedigde, was dat vanuit een geloof in haar eigen boodschap en in de humani generis unitas (eenheid van de menselijke soort), niet vanuit enige zorg om identiteit. Toen de Action Française de Kerk voor de kar van haar Franse identiteitsproject wilde spannen, deed de Kerk haar in de ban. Op dat ene punt ben ik geneigd, de erfenis van de godsdienst van mijn jeugd trouw te blijven.

Zodus, ik identificeer mij –c'est le cas de le dire– niet met de 'identitaire' stroming die in dit boek aan het woord is. Ik neem het de multiculturalisten echter kwalijk dat zij het belang van identiteit enorm opgeblazen hebben juist door hun kruistocht ertegen. En ik herken een bondgenoot wanneer ik er een zie: Friberg is een strijder tegen het cultuurmarxistische kwaad, die in die strijd volop zijn morele en intellectuele kwaliteiten heeft kunnen scherpen en bewijzen.

10:23 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Nouvelle Droite | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : daniel fridberg, koenraad elst, nouvelle droite, vraie droite, livre, nouvelle droite suédoise, métapolitique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 13 avril 2013

De vedische zieners

De vedische zieners

Koenraad Elst

Ex: http://www.alfredvierling.com/

Aardrijkskundige en geschiedkundige situering

De vedische hymnen werden volgens de vedische overlevering zelf hoofdzakelijk gecomponeerd in de schoot van de Paurava-stam, de stam van Puru, één van de vijf zonen van Yayāti, een prins van de Maandynastie uit Prayāg (later bekend als Allāhābād) en veroveraar van het bovenstroomgebied van de Sarasvatī in het noordwesten van India. Deze was via een gemeenschappelijke voorvader, Manu Vaivasvata die de zondvloed overleefde, verwant met de Zonnedynastie uit Ayodhyā, waartoe Rāma (en later ondermeer ook de Boeddha) behoorde. Eén van de eerste Paurava-koningen heette Bharata. Het is naar hem dat India zichzelf nog steeds Bhāratavarsa of kortweg Bhārat noemt.

De vedische hymnen werden volgens de vedische overlevering zelf hoofdzakelijk gecomponeerd in de schoot van de Paurava-stam, de stam van Puru, één van de vijf zonen van Yayāti, een prins van de Maandynastie uit Prayāg (later bekend als Allāhābād) en veroveraar van het bovenstroomgebied van de Sarasvatī in het noordwesten van India. Deze was via een gemeenschappelijke voorvader, Manu Vaivasvata die de zondvloed overleefde, verwant met de Zonnedynastie uit Ayodhyā, waartoe Rāma (en later ondermeer ook de Boeddha) behoorde. Eén van de eerste Paurava-koningen heette Bharata. Het is naar hem dat India zichzelf nog steeds Bhāratavarsa of kortweg Bhārat noemt.

In de Veda’s worden alle Paurava’s, vriend of vijand, Ārya genoemd, “volksgenoot”, dezelfde betekenis die dit woord heeft in het Iraans en het Anatolisch. Omgekeerd wordt geen enkele niet-Paurava, of hij nu vriend of vijand was, zo genoemd. Naarmate de vedische traditie normatief en nagebootst werd, ging Ārya “vedisch, beschaafd” betekenen.

De absolute chronologie van de Veda’s is een heikele kwestie. De meeste handboeken geven de data uit de theorie van westerse oriëntalisten weer, namelijk ruwweg 1500 tot 1000 v.Chr. De inheemse chronologie, ondersteund door enkele sterrenkundige gegevens in de vedische literatuur zelf, situeert de oudste teksten in het 4de millennium v.Chr., met jongere teksten tot in het 2de millennium, met als één van de jongste de Jyotisa-Vedānga, die zichzelf via sterrenkundige gegevens expliciet rond 1350 (of 1800) v.Chr. dateert.

Een open vraag is die naar het verband tussen de vedische literatuur en de archeologische vondsten in steden als Harappa en Kalibangan, samen de grootste beschaving van het 3de millennium v.Chr. Enerzijds een enorme literatuur zonder materiële resten, anderzijds een massa archeologische resten zonder enige literatuur (zgn. David Frawley’s paradox): het suggereert dat we met twee helften van één beschaving te maken hebben. Maar zolang de flarden teksten op Harappa-zegels niet ontcijferd zijn, blijft het mogelijk dat zij een taal weergeven die niets met het vedische Sanskrit te maken heeft. Het onderzoek gaat verder.

Nadien verspreidde de vedische samenleving naar het oosten en zuiden. Dit was deels genoodzaakt door een opdroging van de noordwestelijke zone, deels omdat vorsten daar zich het prestige van de vedische beschaving wilden eigen maken.

De Mahābhārata-oorlog markeert het einde van de vedische periode. De vader of grootvader van de meeste protagonisten, Krsna Dvaipayana alias Vyāsa, was de eindredacteur die volgens de hindoe-overlevering de vedische collecties hun definitieve vorm gaf. We zien van dan af een verschuiving van de vedische god Indra naar de vergoddelijkte historische figuur Krsna Vāsudeva, een prins die als wagenmenner aan de veldslag deelneemt. Volgens westerse geleerden vond die oorlog (als hij al historisch is) plaats rond 900 v.Chr., volgens de hindoetraditie en de meeste hindoes in of rond 3139 v.Chr. Zelf sluit ik mij aan bij de minderheidsopinie die voor zowat de 15de eeuw v.Chr. kiest, precies de tijd van de zo centrale oorlogvoering met strijdwagens (zie gelijktijdig de Egyptisch-Hittitische oorlog of in de 13de eeuw de oorlog om Troje), niet betuigd vóór 2200 v.Chr. Het epos vermeldt ook dat de volle maan nabij de ster Regulus (Magha) nà de winterevening plaatsvond, wat pas na 2300 v.Chr. kon.

Vier hymnencollecties en aanhangsels

Drie vedische samhitā’s (collecties): Rk/“hymne”-, Sāma/“melodie”-, Yajuh/“offerspreuk”-Veda-Samhitā, vormen het Veda-drievoud. Zij bestaan uit hymnen aan de goden, gecomponeerd door mensen. Merk de tegenstelling met de Tien Geboden of de Koran, die geacht worden door God aan de mensen gericht te worden. Moderne hindoes zien de Veda’s als apauruseya, “onpersoonlijk”, en interpreteren dit als “geopenbaard”, precies zoals de Koran of de Tien Geboden; maar de vedische hymnen zelf pleiten daartegen, want zij worden door de mens aan een godheid gericht.

Deze hymnen bevatten enkele kosmologische bespiegelingen en terloops ook een aantal geschied- en aardrijkskundige gegevens. De invloedrijke hervormingsbeweging Ārya Samāj duidde deze concrete gegevens, bv. plaats- en persoonsnamen, als symbolen voor bewustzijnstoestanden, maar daar kan je niets mee aanvangen. De Sāma-Veda-Samhitā herneemt een deel van de Rg-vedische hymnen, maar dan in gezongen vorm. De jongere Yajur-Veda-Samhitā is vooral begaan met het offerritueel, wat de duiding van de twee oudere Veda’s beïnvloed heeft. Sommige hymnen worden in rituelen gebruikt, andere niet.

Pas later is hier de Atharva/“offerpriester”-Veda-Samhitā aan toegevoegd. Hij heeft minder prestige, mogelijk wegens de behandeling van toverij, inbegrepen bezweringen met genezende kracht; of wegens de Perzische invloed daarin. Figuren, producten of ideeën uit het noordwesten (het huidige Pakistan) werden altijd een beetje miszien.

De Rg-Veda-Samhitā omvat 1028 hymnen (sūkta, < su-vakta, “goed gezegd), meestal gesteld in de vorm van een aanroeping van een met name genoemde godheid door de in een aparte index (anukramanī) met name genoemde componist of rsi, “ziener”. Zij zijn uiteraard in versvorm (mantra) met vast metrum, waarbij bepaalde lettergrepen op hogere of lagere toon gereciteerd worden, dit mede als geheugensteun. Zij zijn gegroepeerd in tien boeken (mandala’s), waarvan de volgorde uit het oorspronkelijk aantal hymnen voortkomt, wat echter deels gemaskeerd werd doordat er tijdens het redactieproces nog hymnen bijgekomen zijn. De historische volgorde is, spijts overlappingen, 6-3-7-2-4-5, dan 1 en 8, dan 9 en dan 10. Boeken 2-7 heten de “familieboeken” omdat zij telkens door één familie zieners opgesteld zijn. Boek 8 was de oorspronkelijke afsluiter, en was net als het inleidend boek 1 ook een verzamelwerk uit verschillende families.

Boek 9 is toegevoegd aan een bestaand geheel, nl. de eerste acht boeken. Het bestaat uit hymnen van rsi’s (“zieners”) uit alle vedische families, gericht aan de Soma (“sap”, “geperst”), het aftreksel van een psychotropische plant. Jawel, de zieners waren nog geen saaie geleerden maar eerder trippende dichters. Dit geeft voedsel aan de theorie van Mircea Eliade dat yoga voortkwam uit het sjamanisme: de Veda’s bevatten nog sjamanistische elementen zoals geestreizen met behulp van geestesverruimende planten. Boek 10 kwam nog later, het is duidelijk jonger in taal.

Bijkomende literatuur

Bij elk van de collecties horen een aantal bijkomende geschriften, deels in vers maar grotendeels in proza, te groeperen in drie opeenvolgende categorieën: Brāhmana’s/“priesterboeken”, Āranyaka’s/“woudboeken”, en Upanisad-en/“zitten aan de voet van (de meester)”, vandaar “vertrouwelijk onderricht, geheimleer”. In de eerste categorie ligt de klemtoon op de praktische instructies voor het ritueel, al komen er ook wijsgerige passages in voor. In de tweede categorie verschuift de klemtoon naar de symbolische interpretatie van het ritueel, dat in de derde categorie grotendeels uit het zicht verdwijnt en plaats maakt voor diepzinnige wijsbegeerte.

Volgens de 19de-eeuwse wijsgeer Arthur Schopenhauer zijn de Oepanisjaden het hoogste wat de menselijke geest ooit heeft voortgebracht; in ieder geval bevatten ze een geestelijke revolutie, namelijk de verschuiving van karmakānda, rituele godsdienstoefeningen, naar jñānakānda, bewustzijnscultuur. Het brandpunt van de belangstelling is niet langer de godenwereld, maar het Zelf (ātman).

Van materiëlere aard zijn de zes hulpwetenschappen/Vedānga’s van de vedische traditie: Vyākarana, “spraakkunst”; Śiksā, “eufonie, uitspraakleer”: Candas, “metrum, versbouw”; Nirukta, “etymologie”; Jyotisa, “sterrenkunde”; en Kalpa, “gelijkenis, procedure, ritueel”. Deze laatste categorie van eerder technische teksten met alle mogelijke details over alle mogelijke private en openbare rituelen bevat interessante aanzetten tot exacte wetenschap, bv. sterrenkundige kennis om te bepalen wanneer rituelen moeten plaatsvinden, of meetkundige kennis (inbegrepen de oudste formulering van de stelling van Pythagoras) in de voorschriften voor de bouw van een vedisch altaar.

Daarnaast zijn er de wereldse “ondergeschikte wetenschappen” of Upaveda’s zoals Dhanur-Veda, “krijgskunde”; Artha-Śāstra, “kennis van het wereldse succes”, staatkunde en economie; Gāndharva-Veda, “musicologie”; en tenslotte Āyur-Veda, “kennis van de levensspanne”, gezondheidskunde alias geneeskunde. Men rangschikt de Āyur-Veda bij de aanhangselen van de Atharva-Veda omdat deze laatste ook bezweringen inzake ziekte en gezondheid bevat. De studie van de oudste geneeskundige teksten maakt echter zonneklaar dat zij op kruidenkundige praktijk en empirische waarneming van ziektebeelden gebaseerd zijn, en alleen om redenen van schriftuurlijk prestige aan de Atharva-Veda gekoppeld worden.

Tenslotte zijn uit al deze intellectuele bedrijvigheid nog de volgende vier disciplines voortgekomen: Mīmānsā, “duiding, exegese”; Nyāya, “oordeel, logica”; Purāna, “oudheid, geschiedenis”, weliswaar overlopend in mythologie; en Dharma-Śāstra, “ethiek”, maatschappelijke plichtenleer, sociologie. De eerste twee zijn het begin van de “zes standpunten” of wijsgerige scholen, met als overige vier Sānkhya, “opsomming”, elementenleer, dualistische kosmologie; Vaiśesika, “onderscheiding van bijzonderheden”, pluralistische kosmologie; Yoga, “beheersing”, leer van de controle over het gedachtenleven; en Uttara-Mīmānsā, “latere duiding” alias Vedānta, “het sluitstuk van de Veda”, d.w.z. de monistische uitwerking van de oepanisjadische leer van het Zelf.

Tenslotte zijn uit al deze intellectuele bedrijvigheid nog de volgende vier disciplines voortgekomen: Mīmānsā, “duiding, exegese”; Nyāya, “oordeel, logica”; Purāna, “oudheid, geschiedenis”, weliswaar overlopend in mythologie; en Dharma-Śāstra, “ethiek”, maatschappelijke plichtenleer, sociologie. De eerste twee zijn het begin van de “zes standpunten” of wijsgerige scholen, met als overige vier Sānkhya, “opsomming”, elementenleer, dualistische kosmologie; Vaiśesika, “onderscheiding van bijzonderheden”, pluralistische kosmologie; Yoga, “beheersing”, leer van de controle over het gedachtenleven; en Uttara-Mīmānsā, “latere duiding” alias Vedānta, “het sluitstuk van de Veda”, d.w.z. de monistische uitwerking van de oepanisjadische leer van het Zelf.

Purāna wordt de titel van 18 geschiedkundig-mythologische compendia met alle mogelijke verhalen over zowel godheden en vergoddelijkte mensen als over historische koningen, huwelijken en veldslagen. Sommige verhalen gebruiken de vedische zieners als hoofdfiguur; soms zijn zij volledig onhistorisch en later bedacht; maar soms bewaren zij zeer oude kennis. De schier onmogelijke kunst bestaat erin, het kaf van het koren te scheiden. Qua thematiek gaat deze literatuur in de middeleeuwen over in de Tantra’s, “systemen”, “handboeken”. De Dharma-Śāstra’s, tenslotte, zijn de teksten over de onderscheiden plichten van de leden van de samenleving naargelang geslacht, levensfase en kaste. Zij zijn deels normatief maar deels ook gewoon beschrijvend, en vertonen dan ook een inhoudelijke evolutie in functie van veranderende maatschappelijke zeden.

De epische literatuur noemt men Itihāsa, uit iti-ha-āsa, “zo inderdaad was het”, te vergelijken met het “er was eens” in onze sprookjes. In het moderne Hindi is dit de normale term voor “geschiedenis”. Inhoudelijk loopt zij over in de Purāna-literatuur, maar als Itihāsa beduidt men specifiek de twee grote epen, de Rāmāyana en de Mahābhārata. Dit zijn verhalencycli met een vagelijk historisch kernverhaal, nadien rijkelijk bijgekleurd, en daarin verweven tal van subplots en gastverhalen, vaak van nog oudere oorsprong. Bovendien is er voortdurend aan bijgeschreven tot de eindredactie, die pas in de laatste eeuwen vóór Christus plaatsvond. Beide epen hebben een opvoedende bedoeling, een soort mega-zedenles over het sleutelbegrip dharma, min of meer “plichtenleer”, “integratie in de wereldorde”.

De Bhagavad-Gītā, “lied des Heren”, vormt een kerndeel van de Mahābhārata. Het vat de vedische en andere filosofieën samen maar introduceert een nieuw en later sterk dominant element, nl. bhakti, “devotie”, bv. tot de vergoddelijke Krsna. Voor een juist begrip van het levende hindoeïsme is kennis van de epen belangrijker dan kennis van de Veda’s, waaraan men wel lippendienst betuigt maar die slechts bij specialisten bekend zijn.

De belangrijkste zieners

Eigen Indiase etymologie leidt rsi, “ziener”, af uit de stam rs, “gaan, bewegen, reiken (naar de hogere wereld door kennis)”. Het woord zou echter verwant kunnen zijn met Iers arsan, “oude, wijze”; of met Germaans razen, “in extase zijn” (Manfred Mayrhofer). Het zou ook kunnen komen van een Indo-Europese stam h3er-s-, “rijzen, uitsteken”, in de zin van “uitstekend zijn” (Julius Pokorny). Men hoort ook vaak Monier Monier-Williams’ 19de-eeuwse suggestie dat het om een verbastering gaat van *drsi, wat heel letterlijk “ziener” betekent. Hoe dat ook zij, hier volgen de bekendste vedische zieners.

Bharadvāja was de hoofdauteur van het oudste, 6de boek, en een tijdgenoot van koning Bharata. Traditioneel wordt hem grote geleerdheid en meditatiekracht toegeschreven. Hij was een zoon van Brhaspati, kleinzoon van Angiras, samen het drievoud/Traya genoemd, en een voorouder van Drona. Zijn hermitage (āśrama) bij Prayāg bestaat nog steeds. Zijn grootvader Angiras was ook co-auteur met Atharva van de Atharva-Veda.

Viśvāmitra is de hoofdauteur van meeste van boek 3, inbegrepen de Gāyatrī mantra. Verhaald wordt in de Rāmāyana, hoofdstuk Bālakanda, dat hij de achterkleinzoon van koning Kuśa (niet te verwarren mat Rāma’s zoon Kuśa) was en daarom Kauśika genoemd werd. In de Mahābhārata, hoofdstuk Ādiparva, wordt verhaald hoe hij betrekkingen had met de nimf Menakā, gezonden door Indra om zijn ascese te testen, waaruit Śakuntalā voortkwam, die hij niet erkende; hij vervloekte zijn minnares omdat ze zijn ascese gebroken had. Het Puranisch verhaal situeert deze asceseoefeningen in het kader van zijn rivaliteit met de ziener Vasistha om de gunst van koning Sudās, Hij wilde Vasistha’s koe Nandinī, gift van Indra en dochter van diens koe Kāmadhenu. Na vernedering door Vasistha zag hij de macht van ascese, beoefende ze en gaf er zijn koninkrijk voor op. Hij werd een Brahmarsi (een ziener die Brahma kent; een priester) en kreeg de naam Viśvāmitra.

Vasistha, hoofdauteur van het 7de boek, waaronder de Mrtyuñjaya mantra. Speelde een rol in Sudās’ zege in de Slag van de Tien Koningen. Hij en koning Bhava zijn de enige mensen aan wie een hymne uit de Veda’s gewijd is. Hij had een gurukula (“leermeesterfamilie”, verblijfsschool) aan de Beas-rivier met zijn vrouw Arundhatī. Hun namen worden nu nog gebruikt voor de sterren Mizar en Alcor in de Grote Beer. De leermeester van Rāma, hofpriester van diens vader, heette ook Vasistha. Hoewel Rāma in de vedische tijd gesitueerd wordt (Krsna op het einde ervan), hoeft het niet om dezelfde persoon te gaan; het was een talrijke familie. Ze was herkenbaar, want zieners van die familie droegen hun haarknoetje rechts.

Grtsamada was de auteur van 36 van de 43 hymnes uit Mandala 2 (daarnaast zijn hymne 27-29 door zijn zoon Kurma gecomponeerd, en 4-7 door Somahuti), behoort tot de familie Angiras, bekend van het zesde boek, maar werd door de wil van Indra overgedragen aan de familie Bhrgu.

Vāmadeva, is de belangrijkste auteur van boek 4. Later werd hij vereenzelvigd met één van de vijf aspecten van para-Śiva, namelijk het dichterlijke, vredige, gracieuze. Links (Vāma) is noord als je de opgaande zon begroet, vandaar beduidt hij het noordelijke aspect.

Atri, auteur van sommige hymnen het 5de boek, werd later beschouwd als vader van ondermeer Dattātreya en, warempel (met overbrugging van enkele eeuwen) Patañjali. De Rāmāyana verhaalt dat Rāma hem bezocht in het woud tijdens zijn ballingschap (evenals de āśrama’s van Agastya en Gautama). Hij werd eeuwen later nog eens opgetrommeld om Drona tijdens de Mahābhārata-veldslag te kalmeren.

Kanva, Kaksīvān, Gotama en Parāśara zijn bekende zieners uit boek 1, evenals Agastya en Dīrghatamas. Laatstgenoemde was de hofpriester van koning Bharata, auteur van hymne 140-164, met 164 als één van de rijkste en bekendste hymnen. We vinden er voor het eerst de sterrenkundige hemelindeling in 360; het yogische inzicht dat dadendrang en waarneming twee complementaire bezigheden zijn, hier verbeeld door twee vogels waarvan de ene vruchten eet en de andere slechts toekijkt; en “de lettergreep”, wat kennelijk op aum/om duidt.

Agastya was gehuwd met Lopāmudrā, die hem in een duo-hymne smeekt om geslachtsverkeer en nageslacht. Hij bracht de vedische rituelen naar het Vindhyā-gebergte in het zuiden; de zuidelijke ster Canopus is naar hem genoemd.

Kaśyapa is de naam van een ziener, maar ook van de vader der goden (Āditya’s), die hij verwekte bij zijn hoofdvrouw Aditī. Hij was de stichter van het naar hem genoemde Kaśmīr, dat hij drooglegde.

Bhrgu wordt geassocieerd met het vuuroffer, centrum van de vedische bedrijvigheid. Zijn naam is verwant met Brigit, aan wie in Ierland een vuurtempel gewijd was, met de Griekse vuurpriesters of phleguai, en kennelijk ook met de landsnaam Phrygia. Hij was de vader van de ziener Śukra. Het astrologisch handboek Bhrgu Samhitā wordt aan hem toegeschreven. Het betreft de nu gebruikelijke hellenistische horoscopie, met de bekende Dierenriem van twaalf tekens.

Jamadagni was een afstammeling van Bhrgu, met vrouw Renukā vader van Jāmadagni ofte Paraśurāma. Dit is kennelijk een Puranische verhaspeling van Parśurāma, “de Perzische Rāma”, want hij was net als zijn voorvader Bhrgu van Iraanse afkomst.

De “zeven rsi’s”

De zeven sterren van de Grote Beer worden in India de Sapta-rsi, “zeven zieners”, genoemd. Eerste versie: Grtsamada, Vāmadeva, Atri, Angiras, Vasistha, Viśvāmitra, Bharadvāja, Kanva.

Tweede versie in de Śatapatha Brāhmana: Jamadagni, Bharadvāja, Vasistha, Viśvāmitra, Kaśyapa, Atri, Gautama (= Uddālaka Āruni), later uitgebreid met Pracetas/Daksa, Bhrgu, Nārada, samen de tien “heren der schepselen”.

Derde versie, specifiek betrekking hebbend op het vroegere eerste Manu-tijdperk, vinden we in de Mahābhārata: Marici, Pulaha, Pulastya (vader van Agastya, langs andere zoon grootvader van Rāma’s tegenstander Rāvana), Vasistha, Atri, Angiras, Kratu.

Niet in de Veda’s

Wat er niét in de Rg-Veda staat, hoewel tegenwoordig toch “vedisch” genoemd:

· Wedergeboorte en de bijbehorende werking-op-afstand/karma (wel karma als “ritueel”), beide verschijnen samen in de Chândogya Upanisad.

· Asceten: zwerfmonniken worden slechts vermeld (“naakt en modderig”) als een bestaande beweging, maar waar de zieners zelf duidelijk niet toe behoorden.

· Verlichting/bevrijding. Pas in de Upanisaden duikt de bevrijding (mukti) uit de onwetendheid (avidyâ) op als streefdoel. De wereld als tranendal en de nood om dááruit te ontsnappen daagt voorzichtig aan de horizon in de Sânkhya-wijsbegeerte, waarvan de we eerste sporen ook in de Upanisaden aantreffen, maar komt pas echt in het centrum met het boeddhisme. De vedische hymnen daarentegen zijn levenslustig. Het doel van rituelen en zelfs van zelfkastijding is werelds geluk in allerlei vormen.

· Ideaal van geweldloosheid, vegetarisme, onschendbaarheid van de koe.

· Goddelijke openbaring. Anders dan beweerd profetische teksten (Tien Geboden, Qur’ān) geven de vedische hymnen volstrekt niet voor, van goddelijke oorsprong te zijn. Zij worden door mensen, de zieners die met naam bekend zijn, vaak zelfs met stamboom en levensschets, tot één of meerdere van de (“33”) goden gericht. Zij zijn mensenwerk.

· Tempels en beeldenverering: onbekend in de Veda’s en in de Harappa-steden. Duiken pas op na Alexander o.i.v. de Grieken (die ze zelf aan het Midden-Oosten ontleend hadden). Idem voor de zoeterigheid en extreme onderdanigheid typisch voor het middeleeuwse en moderne Bhakti (devotie) tegenover goden en goeroes.

· Astrologie, d.i. sterrenwichelarij. Wel sterrenkunde, bv. berekening van verhouding maanmaand/zonnejaar. Een aanhangsel bij Atharva-Veda bevat embryonale astrologie, echter grondig verschillend van de Babylonisch-Hellenistische die nu “vedisch” heet. De echte vedische astrologie betrof geen persoonlijke horoscopie, wel het bepalen van gunstige tijdstippen voor rituelen (nu nog voor bruiloften) met een Dierenriem van 27 of 28 “maanhuizen”.

· Kundalinī en de cakra’s: verschijnen pas in middeleeuwse teksten.

· Hatha-yoga-āsana’s. Pas uit de late middeleeuwen. Tot dan alleen “aangename doch stevige zithouding” als lichamelijke grondslag voor meditatie, reeds afgebeeld op Harappa-zegels. Wel vanaf het begin eenvoudige Prānāyāma.

Wel kiemen daarvan:

· Monisme: “Hij die in de zon leeft, hem ben ik” (so’ham); het Brahman is in de mens.

· Polymorf theïsme: “De wijzen noemen het Ene Ware met vele namen.”

· Kosmisch corporatisme: heelal en samenleving vergeleken met menselijk lichaam met organische samenhang tussen alle leden. Bandhu, overeenkomst/resonantie tussen verschillende bestaansdomeinen (Zo boven, zo beneden).

· Onthechting: “Twee vogels, de ene eet vruchten en de andere kijkt slechts toe.”

· Agnosticisme, skepsis: de geheimen van de schepping, “misschien kent ook Hij ze niet.”

· Meditatie, of althans verstilling om voor hymnische inspiratie open te staan.

00:05 Publié dans Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : tradition, védas, inde, inde védique, traditionalisme, koenraad elst |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 12 janvier 2013

Islam In India

Islam In India: William Dalrymple’s jihad negationism

Dr. Elst defends Naipaul's views

Koenraad Elst

Ex: http://www.alfredvierling.com/

Taj Mahal

In several articles and speeches since at least 2004 (“Trapped in the ruins” in The Guardian, 20 March 2004), and especially in the commotion provoked by Girish Karnad’s speech in Mumbai (autumn 2012), William Dalrymple has condemned Nobel prize winner V.S. Naipaul for writing that the Vijayanagar empire was a Hindu bastion besieged by Muslim states. The famous writer has taken the ruins of vast Vijayanagar as illustration of how Hinduism is a “wounded civilization”, viz. wounded by Islam. Dalrymple’s counter-arguments against this conflictual view of Indian history consist in bits of Islamic influence in the Vijayanagar kings’ court life, such as Hindu courtiers wearing Muslim dress, Hindu armies adopting techniques borrowed from the Muslims, styles of palace architecture and the Persian nomenclature of political functions; and conversely, elements of Hinduism in Muslims courts and households, e.g. the Muslim festival of Muharram looking like the Kumbha Mela of the Hindus.

V.S. NaipaulSecularism and Vijayanagar

As is all too common in Nehruvian-secularist discourse, Dalrymple’s analysis of the role of Islam in India stands out by its superficiality. Whenever a Hindu temple or a Muslim festival is found to employ personnel belonging to the opposite religion, secular journalists go gaga and report on this victory of syncretism over religious orthodoxy. Secular historians including Dalrymple do likewise about religious cross-pollination in the past.

It is true that Hindus are eager to integrate foreign elements from their surroundings, from Hellenistic astrology (now mis-termed “Vedic astrology”) in the past to the English language and American consumerism today. So Hindu courts adopted styles and terminology from their Muslim counterparts. They even enlisted Muslim mercenaries in their armies, so “secular” were they. We could say that Hindus are multicultural at heart, or open-minded. But that quality didn’t get rewarded, except with a betrayal by their Muslim regiments during the battle of Talikota (1565): they defected to the enemy, in which they recognized fellow-Muslims. When the chips were down, Hindu open-mindedness and syncretism were powerless against their heartfelt belief in Islamic solidarity. In September 2012, Dalrymple went to Hyderabad to praise the city and its erstwhile Muslim dynasty as a centre of Hindu-Muslim syncretism; but fact is that after Partition, the ruler of Hyderabad opted for Pakistan, against multicultural India. When the chips are down, secular superficiality is no match for hard-headed orthodoxy.

William DalrympleMuslims too sometimes adopted Hindu elements. However, it would be unhistorical to assume a symmetry with what the Hindus did. Hindus really adopted foreign elements, but most Muslims largely just retained Hindu elements which had always been part of their culture and which lingered on after conversion. Thus, the Pakistanis held it against the Bengalis in their artificial Muslim state (1947-71) that their language was very Sanskritic, not using the Arabic script, and that their womenfolk “still” wore saris and no veils. The Bengali Muslims did this not because they had “adopted” elements from Hinduism, but because they had retained many elements from the Hindu culture of their forefathers. “Pakistan” means the “land of the pure”, i.e. those who have overcome the taints of Paganism, the very syncretism which Dalrymple celebrates. Maybe it is in the fitness of things that a historian should sing paeans to this religious syncretism for, as far as Islam is concerned, it is a thing of the past.

A second difference between Hindus and Muslims practicing syncretism is that in the case of Muslims, this practice was in spite of their religion, due to a hasty (and therefore incomplete) conversion under duress and a lack of sufficient policing by proper Islamic authorities. If, as claimed by Dalrymple, a Sultan of Bijapur venerated both goddess Saraswati and prophet Mohammed, it only proves that he hadn’t interiorized Mohammed’s strictures against idolatry yet. In more recent times, though, this condition has largely been remedied. Secular journalists now have to search hard for cases of Muslims caught doing Hindu things, for such Muslims become rare. Modern methods of education and social control have wiped out most traces of Hinduism. Thus, since their independence, the Bengali Muslims have made great strides in de-hinduizing themselves, as by widely adopting proper Islamic dress codes. The Tabligh (“propaganda”) movement as well as informal efforts by clerics everywhere have gone a long way to “islamize the Muslims”, i.e. to destroy all remnants of Hinduism still lingering among them.

Hindu iconoclasm?

Another unhistorical item in the secular view of Islam in India is the total absence of an Islamic prehistory outside India. Yet, all Muslims know about this history to some extent and base their laws and actions upon it. In particular, they know about Mohammed’s career in Arabia and seek to replicate it, from wearing “the beard of the Prophet” to emulating his campaigns against Paganism.

Dalrymple, like all Nehruvians, makes much of the work of the American Marxist historian Richard Eaton. This man is famous for saying that the Muslims have indeed destroyed many Hindu temples (thousands, according to his very incomplete list, though grouped as the oft-quoted “eighty”), but that they based themselves for this conduct on Hindu precedent. Indeed, he has found a handful of cases of Hindu conquerors “looting” temples belonging to the defeated kings, typically abducting the main idol to install it in their own capital. This implies a very superficial equating between stealing an idol (but leaving the worship of the god concerned intact, and even continuing it in another temple) and destroying temples as a way of humiliating and ultimately destroying their religion itself. But we already said that secularists are superficial. However, he forgets to tell his readers that he has found no case at all of a Muslim temple-destroyer citing these alleged Hindu precedents. If they try to justify their conduct, it is by citing Mohammed’s Arab precedents. The most famous case is the Kaaba in Mecca, where the Prophet and his nephew Ali destroyed 360 idols with their own hands. What the Muslims did to Vijayanagar was only an imitation of what the Prophet had done so many times in Arabia, only on a much larger scale.

From historians like Eaton and Dalrymple, we expect a more international view of history than what they offer in their account of Islamic destructions in India. They try to confine their explanations to one country, whereas Islam is globalist par excellence. By contrast, Naipaul does reckon with international cultural processes, in particular the impact of Islam among the converted peoples, not only in South but also in West and Southeast Asia. He observes that they have been estranged from themselves, alienated from their roots, and therefore suffering from a neurosis.

So, Naipaul is right and Dalrymple wrong in their respective assessments of the role of Islam in India. Yet, in one respect, Naipaul is indeed mistaken. In his books Among the Believers and Beyond Belief, he analyses the impact of Islam among the non-Arab converts, but assumes that for Arabs, Islam is more natural. True, the Arabs did not have to adopt a foreign language for religious purposes, they did not have to sacrifice their own national traditions in name-giving; but otherwise they too had to adopt a religion that wasn’t theirs. The Arabs were Pagans who worshipped many gods and tolerated many religions (Jews, Zoroastrians, various Christian Churches) in their midst. Mohammed made it his life’s work to destroy their multicultural society and replace it with a homogeneous Islamic one. Not exactly the syncretism which Dalrymple waxes so eloquent about.

Colonial “Orientalism”?

Did Muslims “contribute” to Indian culture, as Dalrymple claims? Here too, we should distinguish between what Islam enjoins and what people who happen to be Muslims do. Thus, he says that Muslims contributed to Indian music. I am quite illiterate on art history, but I’ll take his word for it. However, if they did, they did it is spite of Islam, and not because of it. Mohammed closed his ears not to hear the music, and orthodox rulers like Aurangzeb and Ayatollah Khomeini issued measures against it. Likewise, the Moghul school of painting shows that human beings are inexorably fond of visual art, but does not disprove that Islam frowns on it.

Also, while some tourists fall for the Taj Mahal, which Naipaul so dislikes, the Indo-Saracenic architecture extant does not nullify the destruction of many more beautiful buildings which could have attracted far more tourists. In what sense is it a “contribution” anyway? Rather than filling a void, it is at best a replacement of existing Hindu architecture with new Muslim architecture. Similarly, if no Muslim music (or rather, music by Muslims) had entered India, then native Hindu music would have flourished more, and who is Dalrymple to say that Hindu music is inferior?

Another discursive strategy of the secularists, applied here by Dalrymple, is to blame the colonial view of history. Naipaul is said to be inspired by colonial Orientalists and to merely repeat their findings. This plays on the strong anti-Westernism among Indians. But it is factually incorrect: Naipaul cites earlier sources (e.g. Dalrymple omits Ibn Battuta, the Moroccan traveler who only described witnessed Sultanate cruelty to the Hindus with his own eyes) as well as the findings of contemporaneous archaeologists. Moreover, even the colonial historians only repeat what older native sources tell them. The destruction of Vijayanagar is a historical fact and an event that took place with no colonizers around. Unless you mean the Muslim rulers.

Negationism

In the West, we are familiar with the phenomenon of Holocaust negationism. While most people firmly disbelieve the negationists, some will at least appreciate their character: they are making a lot of financial, social and professional sacrifices for their beliefs. The ostracism they suffer is fierce. Even those who are skeptical of their position agree that negationists at least have the courage of their conviction.

In India, and increasingly also in the West and in international institutions, we are faced with a similar phenomenon, viz. Jihad negationism. This is the denial of aggression and atrocities motivated by Islam. Among the differences, we note those in social position of the deniers and those in the contents of the denial. Jihad deniers are not marginals who have sacrificed a career to their convictions, on the contrary; they serve their careers greatly by uttering the politically palatable “truth”. In India, any zero can become a celebrity overnight by publishing a condemnation of the “communalists” and taking a stand for Jihad denial and history distortion. The universities are full of them, while people who stand by genuine history are kept out. Like Jawaharlal Nehru, most of these negationists hold forth on the higher humbug (as historian Paul Johnson observed) and declare themselves “secular”.

Whereas the Holocaust lasted only four years and took place in war circumstances and largely in secret (historians are still troubled over the absence of an order by Adolf Hitler for the Holocaust, a fact which gives a handle to the deniers), Jihad started during the life of Mohammed and continues till today, entirely openly, proudly testified by the perpetrators themselves. From the biography and the biographical collections of the Prophet (Sira, Ahadith) through medieval chronicles and travel diaries down to the farewell letters or videos left by hundreds of suicide terrorists today, there are literally thousands of sources by Muslims attesting that Islam made them do it. But whereas I take Muslims seriously and believe them at their word when they explain their motivation, some people overrule this manifold testimony and decide that the Muslims concerned meant something else.

The most favoured explanation is that British colonialism and now American imperialism inflicted poverty on them and this made them do it, though they clothed it in Islamic discourse. You see, the billionaire Osama bin Laden, whose family has a long-standing friendship with the Bush family, was so poor that he saw no option but to hijack some airplanes and fly them into the World Trade Center. What else was he to do? And Mohammed, way back in the 7th century, already the ruler of Medina and much of the Arabian peninsula, just had to have his critics murdered or, as soon as he could afford it, formally executed. He had to take hostages and permit his men to rape them; nay, he just had to force the Jewish woman Rayhana into concubinage after murdering her relatives. If you don’t like what he did, blame Britain and America. Their colonialism and imperialism made him do it! Under the colonial dispensation which didn’t exist yet, the Muslim troops who were paid by the Vijayanagar emperor had no other option but to betray their employer and side with his opponents who, just by coincidence, happened to be Muslim as well. And if you don’t believe this, the secularists will come up with another story.

Conclusion

India is experiencing a regime of history denial. In this sense, the West is more and more becoming like India. There are some old professors of Islam or religion (and I know a few) who hold the historical view, viz. that Mohammed (if he existed at all) was mentally afflicted, that Islam consists of a manifold folie à deux (“madness with two”, where a wife supports and increasingly shares her husband’s self-delusion), and that it always was a political religion which spread by destroying other religions. But among the younger professors, it is hard to find any who are so forthright. There is a demand for reassurance about Islam, and universities only recruit personnel who provide that. Indeed, many teach false history in good faith, thinking that untruth about the past in this case is defensible because it fosters better interreligious relations in the present. Some even believe their own stories, just like the layman who is meant to lap them up. Such is also my impression of William Dalrymple.

– Koenraad Elst, 30 December 2012

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Islam | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : inde, islam, islamisme, koenraad elst, naipaul, dalrymple, djihad |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 22 décembre 2012

Lezingen door Dr. Koenraad Elst

Beste vrienden,

noteer alvast in uw agenda de volgende lezingen door dr. Koenraad Elst, oriëntalist, telkens om 20u:

Maandag 21 januari, zaal 't Parkske, Edegemsestraat 26, Mortsel: "Kalenders en eindtijdverwachtingen".

Maandag 28 januari, zaal 't Parkske, Edegemsestraat 26, Mortsel: "Filosofieën van de dierenriem".

Maandag 4 februari: zaal 't Parkske, Edegemsestraat 26, Mortsel: "Het Boek der Veranderingen en het yin/yang-denken, sleutel tot de Chinese beschaving".

Maandag 11 februari: zaal 't Parkske, Edegemsestraat 26, Mortsel: "De ware vedische astrologie".

Maandag 25 februari: zaal 't Parkske, Edegemsestraat 26, Mortsel: "Het Turkse wereldbeeld. De eigen Turkse mythologie".

Tot daar en dan,

Koenraad Elst

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Evénement | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : koenraad elst, événement, flandre |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 08 octobre 2012

Reeks lezingen door dr. Koenraad Elst, oriëntalist

"De Lezing"

Reeks lezingen door dr. Koenraad Elst, oriëntalist

Dr. Koenraad Elst, oriëntalist, geeft een reeks van drie lezingen over thema's die niet alleen hem maar ook u meer dan gewoon (kunnen) interesseren: Islam, boeddhisme en Ghandi.

Dr. Koenraad Elst schreef fel besproken boeken en zeer veel artikels over de drie onderwerpen in voornamelijk het Nederlands en het Engels. Hem aan het woord horen is leerrijk en verhelderend. Hem lezen is dat minstens evenveel.

Na de lezingen biedt dr. Elst zijn boeken aan en signeert. Er is kans tot vragen en nabespreking.

Voor zeer redelijke prijzen is het mogelijk drank te bekomen.

De eerste lezing is op dinsdag 9 oktober, 20 uur.

De tweede lezing is op dinsdag 13 november, 20 uur.

De derde lezing is op dinsdag 11 december, 20 uur.

Prijs: GRATIS (met dank aan het nieuwe adres).

Drank aan betaalbare prijzen.

Opgelet: aantal plaatsen beperkt tot 25 !

Inschrijven :

http://www.facebook.com/events/469606533069702/

of via

of via

tel 0484 08 45 85

Plaats : Torrestraat 76, Dendermonde.

Belangrijke mededeling :

Dit is GEEN organisatie van Euro-Rus.

De lezingen worden georganiseerd door derden. Zij maken enkel gebruik van de aangeboden faciliteiten.

09:14 Publié dans Actualité, Evénement | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : inde, islam, orientaisme, événement, flandre, koenraad elst |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 20 novembre 2011

India's only communalist A short biography of Sita Ram Goel

India's only communalist

A short biography of Sita Ram Goel

Ex; http://koenraadelst.voiceofdharma.com/

Koenraad Elst

1. Is there a communalist in the hall ?

A lot of people in India and abroad talk about communalism, often in grave tones, describing it as a threat to secularism, to regional and world peace. But can anyone show us a communalist? If we look more closely into the case of any so-called communalist, we find that he turns out to be something else.

Could Syed Shahabuddin be a communalist? After all, he played a key role in the three main "Muslim communalist" issues of recent years: the Babri Masjid campaign, the Shah Bano case and the Salman Rushdie affair (it is he who got The Satanic Verses banned in September 1988). Surely, he must be India's communalist par excellence? Wrong: if you read any page of any issue of Shahabuddin's monthly Muslim India, you will find that he brandishes the notion of "secularism" as the alpha and omega of his politics, and that he directs all his attacks against Hindu "communalism". The same propensity is evident in the whole Muslim "communalist" press, e.g. the Jamaat-i Islami weekly Radiance. Moreover, on Muslim India's editorial board, you find articulate secularists like Inder Kumar Gujral, Khushwant Singh and the late P.N. Haksar.

Could Syed Shahabuddin be a communalist? After all, he played a key role in the three main "Muslim communalist" issues of recent years: the Babri Masjid campaign, the Shah Bano case and the Salman Rushdie affair (it is he who got The Satanic Verses banned in September 1988). Surely, he must be India's communalist par excellence? Wrong: if you read any page of any issue of Shahabuddin's monthly Muslim India, you will find that he brandishes the notion of "secularism" as the alpha and omega of his politics, and that he directs all his attacks against Hindu "communalism". The same propensity is evident in the whole Muslim "communalist" press, e.g. the Jamaat-i Islami weekly Radiance. Moreover, on Muslim India's editorial board, you find articulate secularists like Inder Kumar Gujral, Khushwant Singh and the late P.N. Haksar.

For the same reason, any attempt to label the All-India Muslim League as communalist would be wrong. True, it is the continuation of the party which achieved the Partition of India along communal lines. Yet, emphatically secularist parties like the Congress Party and the Communist Party of India (Marxist) have never hesitated to include the Muslim League in coalitions governing the state of Kerala. No true communalist would get such a chance.

On the Hindu side then, at least the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS, "National Volunteer Corps") could qualify as "communalist"? Certainly, it is called just that by all its numerous enemies. But then, when you look through any issue of its weekly Organiser, you will find it brandishing the notion of "positive" or "genuine secularism", and denouncing "pseudo-secularism", i.e. minority communalism. Moreover, in order to prove its non-communal character, it even calls itself and its affiliated organizations (trade-union, student organization, political party etc.) "National" or "Indian" rather than "Hindu". The allied political party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP, "Indian People's Party"), shows off the large number of Muslims among its cadres to prove how secular and non-communal it is. Even the Shiv Sena shows off its token Muslims. No, for full-blooded communalists, we have to look elsewhere.

There is only one man in India whom I have ever known to say: "I am a (Hindu) communalist." To an extent, this is in jest, as a rhetorical device to avoid the tangle in which RSS people always get trapped: being called "communalist!" and then spending the rest of your time trying to prove to your hecklers what a good secularist you are. But to an extent, it is because he accepts at least one definition of "communalism" as applying to himself, esp. to his view of India's history since the 7th century. Many historians try to prove their "secularism" by minimizing religious adherence as a factor of conflict in Indian history, and explaining so-called religious conflicts as merely a camouflage for socio-economic conflicts. By contrast, the historian under consideration accepts, and claims to have thoroughly documented, the allegedly "communalist" view that the major developments in medieval and modern Indian history can only be understood as resulting from an intrinsic hostility between religions.

Unlike the Hindutva politicians, he does not seek the cover of "genuine secularism". While accepting the notion that Hindu India has always been "secular" in the adapted Indian sense of "religiously pluralistic", he does not care for slogans like the Vishva Hindu Parishad's advertisement "Hindu India, secular India". After all, in Nehruvian India the term "secular" has by now acquired a specific meaning far removed from the original European usage, and even from the above-mentioned Indian adaptation. If Voltaire, the secularist par excellence, were to live in India today and repeat his attacks on the Church, echoing the Hindutva activists in denouncing the Churches' grip on public life in christianized pockets like Mizoram and Nagaland, he would most certainly be denounced as "anti-minority" and hence "anti-secular".

In India, the term has shed its anti-Christian bias and acquired an anti-Hindu bias instead, a phenomenon described by the author under consideration as an example of the current "perversion of India's political parlance". Therefore, he attacks the whole Nehruvian notion of "secularism" head-on, e.g. in the self-explanatory title of his Hindi booklet Saikyularizm: râshtradroha kâ dûsra nâm ("Secularism: the Alternative Name for Treason"). The name of India's only self-avowed communalist is Sita Ram Goel.

2. Sita Ram Goel as an anti-Communist

Sita Ram Goel was born in 1921 in a poor family (though belonging to the merchant Agrawal caste) in Haryana. As a schoolboy, he got acquainted with the traditional Vaishnavism practised by his family, with the Mahabharata and the lore of the Bhakti saints (esp. Garibdas), and with the major trends in contemporary Hinduism, esp. the Arya Samaj and Gandhism. He took an M.A. in History in Delhi University, winning prizes and scholarships along the way. In his school and early university days he was a Gandhian activist, helping a Harijan Ashram in his village and organizing a study circle in Delhi.

In the 1930s and 40s, the Gandhians themselves came in the shadow of the new ideological vogue: socialism. When they started drifting to the Left and adopting socialist rhetoric, S.R. Goel decided to opt for the original rather than the imitation. In 1941 he accepted Marxism as his framework for political analysis. At first, he did not join the Communist Party of India, and had differences with it over such issues as the creation of the religion-based state of Pakistan, which was actively supported by the CPI but could hardly earn the enthusiasm of a progressive and atheist intellectual. He and his wife and first son narrowly escaped with their lives in the Great Calcutta Killing of 16 August 1946, organized by the Muslim League to give more force to the Pakistan demand.

In the 1930s and 40s, the Gandhians themselves came in the shadow of the new ideological vogue: socialism. When they started drifting to the Left and adopting socialist rhetoric, S.R. Goel decided to opt for the original rather than the imitation. In 1941 he accepted Marxism as his framework for political analysis. At first, he did not join the Communist Party of India, and had differences with it over such issues as the creation of the religion-based state of Pakistan, which was actively supported by the CPI but could hardly earn the enthusiasm of a progressive and atheist intellectual. He and his wife and first son narrowly escaped with their lives in the Great Calcutta Killing of 16 August 1946, organized by the Muslim League to give more force to the Pakistan demand.

In 1948, just when he had made up his mind to formally join the Communist Party of India, in fact on the very day when he had an appointment at the party office in Calcutta to be registered as a candidate-member, the Government of West Bengal banned the CPI because of its hand in an ongoing armed rebellion. A few months later, Ram Swarup came to stay with him in Calcutta and converted him as well as his employer, Hari Prasad Lohia, out of Communism. Goel's career as a combative and prolific writer on controversial matters of historical fact can only be understood in conjunction with Ram Swarup's sparser, more reflective writings on fundamental doctrinal issues.

Much later, in a speech before the Yogakshema society, Calcutta 1983, he explained his relation with Ram Swarup as follows: "In fact, it would have been in the fitness of things if the speaker today had been Ram Swarup, because whatever I have written and whatever I have to say today really comes from him. He gives me the seed-ideas which sprout into my articles (...) He gives me the framework of my thought. Only the language is mine. The language also would have been much better if it was his own. My language becomes sharp at times; it annoys people. He has a way of saying things in a firm but polite manner, which discipline I have never been able to acquire." (The Emerging National Vision, p.1.)

S.R. Goel's first important publications were written as part of the work of the Society for the Defence of Freedom in Asia:

· World Conquest in Instalments (1952);

· The China Debate: Whom Shall We Believe? (1953);

· Mind Murder in Mao-land (1953);

· China is Red with Peasants' Blood (1953);

· Red Brother or Yellow Slave? (1953);

· Communist Party of China: a Study in Treason (1953);

· Conquest of China by Mao Tse-tung (1954);

· Netaji and the CPI (1955);

· CPI Conspire for Civil War (1955).