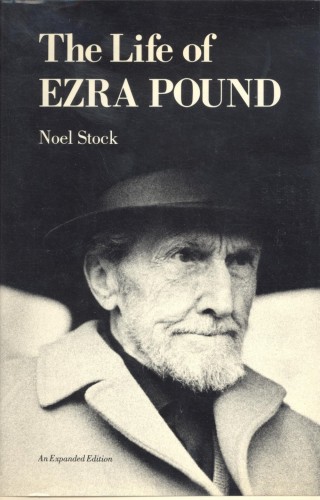

Ezra Pound and the Occult

Ezra Pound and the Occult

Brian Ballentine

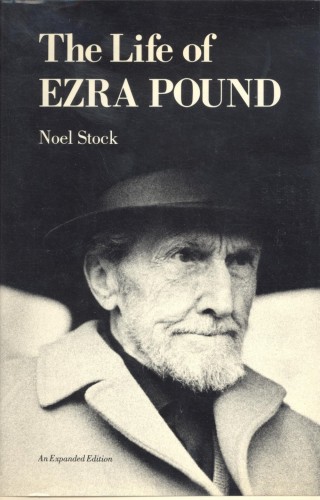

In 1907, when Ezra Pound was still teaching Romance languages at Wabash

College in Indiana, he completed the poem "In Durance":

I am homesick after mine own kind

And ordinary people touch me not.

Yea, I am homesick

After mine own kind that know, and feel

And have some breath for beauty and the arts (King 86).

Pound left America and its "ordinary people" behind for Europe shortly after. When he arrived in London in 1908, Pound wasted no time becoming a part of the community of writers which he considered his "own kind." He was quickly running among the more prestigious of London’s literary society including members from the Rhymer’s Club and W. B. Yeats’s publisher Elkin Mathews. Of course, it was Yeats’s association that Pound truly desired and successfully sought out. In Poetry 1, Pound begins his "Status Rerum" by declaring that he found "Mr. Yeats the only poet worthy of serious study" (123). Pound would eventually be content to condense his esoteric community of cutting edge writers down to two men: himself and Yeats. In 1913 he wrote Harriet Monroe proclaiming that London’s writers are divided into two groups: "Yeats and I in one class, and everybody else in the other" ("Status Rerum" 123).When Pound first met Yeats, the older poet was heavily involved and experimenting with theurgy, or magic, that is performed with the aid of beneficent spirits. This form of occult study was not at all of interest to Pound. Shortly after their introduction, it was arranged for Pound to serve as Yeats’s "secretary" at the winter retreat Stone Cottage. Not trying to hide his skepticism , Pound wrote this letter to his mother just prior to his first winter with Yeats at Stone Cottage:

My stay at Stone Cottage will not be in the least profitable. I detest

the country. Yeats will amuse me part of the time and bore me to

death with psychical research the rest. I regard the visit as a duty to

posterity (Paige 25).

The purpose of this research is to expose the various types of occultism that were prevalent during Pound's life and determine what elements of the occult he subscribed to. Although there are signs of an occult influence all the way through his later writing, Pound’s own stance on the occult is difficult to pin down. Pound’s own belief in the occult was one that was constantly being rethought and revised. There are moments when Pound was on the brink of exploration into Yeats’s world of spirits as well as moments when he was ready to abandon the occult altogether. Pound’s exploration of "retro-cognition," his revitalization

of the Greek idea of the "phantastikon," his pursuit of gnosis or what he termed a "crystal" state, and his associations with some of London’s premiere occultists provide evidence for the former. The latter is demonstrated in his revisions on the original 1917 Three Cantos and his apparent desire to be disassociated with the "pseudo-sciences" of the occult. Much of the occult element that dominated the original publication has been edited entirely out of the final and existing copy. In any case, much of Pound’s writing is indebted to an occult influence and it will be explored in this paper.

In his essay "Ezra Pound’s Occult Education," Demetres Tryphonopoulos warns other critics not to view Pound’s skeptical letter to his mother as a rejection towards all forms of the occult. He states that "it is only theurgy and spiritualism that Pound rejects" (76). These "pseudo-sciences" are what Tryphonopoulos believes to be "the areas of human interest which many true occultists would reject as involving the degradation of humanity" ("Occult Education" 74). Yeats’s other interests in astrology and numerology, both of which were popular in the early twentieth century, are also included among the "pseudo-sciences." Occult studies such as gnosticism and theosophy are understood as legitimate pursuits by scholars like Tryphonopoulos. Gnosis, an esoteric form of knowledge that made possible the direct awareness of the Divine, was one of Pound’s major interests with the occult. James Longenbach argues that Pound labored over creating a "priest-like status" for himself and his work (92). The quest for becoming as close to God as possible led Pound on a long exploration of occult texts. According to Walter Baumann, Pound’s quest drove him to "provide further ingredients for [his] own vision of Paradise" (311). These esoteric components or "ingredients" then become the source of much difficulty in understanding Pound’s work. To date only a few scholars have made the occult element in Pound’s work more accessible and in the past only people "deeply steeped in occult literature" could successfully navigate his writing (Baumann 318). Pound never came so far around as to accept Yeats’s interests in what he considered less useful facets of the occult, but he would humor Yeats. The older poet was also interested in astrology and asked Pound for his birth date so he could determine his horoscope. In a letter to Dorothy Shakespear Pound exclaimed:

The Eagle [Yeats] is welcomed to my dashed horoscope tho’ I

think Horace was on the better track when he wrote

"Tu ne quaesaris, scire nefas, quem

mihi quem tibi

Finem dii dederunt" (Litz 113).

[Ask not, we cannot know, what ends the gods have set for me, for thee]

Despite Pound’s show of pessimism, he provided Yeats with all of the necessary information, which included writing a letter to his mother for the exact time of his birth. He told his mother that "half a million people, some of them intelligent, who still believe in the possibility of planetary influences . . . When astrology is taken hold of systematically by modern science there will be some sort of discoveries. In the meantime there is no reason why one should not indulge in private experiment and investigation (Paige 152).A subject of particular interest to both men is something that psychologists today have termed "retro-cognition." Yeats, Pound and the rest of England received their introduction to this phenomenon when Anne Moberly and Eleanor Jourdain published An Adventure in 1911. On August 10, 1901 the two women claimed to have been strolling through the Versailles gardens and found themselves transported back into the eighteenth century. Apparently, neither of them had realized what had occurred at the time but recounted the experience in a narrative:

We walked briskly forward, talking as before, but from the moment we left the lane an

extraordinary depression had come over me. . . In front of us was a wood, within which,

and overshadowed by trees, was a light garden kiosk, circular and like a small bandstand,

by which a man was sitting. There was no greensward, but the ground was covered by

rough grass and dead leaves as in a wood. The place was so shut that we could not see

beyond it. Everything suddenly looked unnatural, therefore unpleasant; even the trees

behind the building seemed to have become flat and lifeless, like a wood worked in a

tapestry (41).

Ten years of research in the French National Archives led them to believe that all the things they saw that day existed not in 1901 but in 1789. Also, they determined the person Moberly saw by the terrace, who is referred to as a "man" in the narrative, to be Marie Antoinette (Longenbach 222-23).Shortly after the publication of An Adventure, Yeats completed two essays for Lady Gregory’s Visions and Beliefs in the West of Ireland. In his essays, Yeats references An Adventure, making it highly probable that the two men had possession of the book during the Stone Cottage years if not sooner. An Adventure became an important beginning for the work of Pound and how the artist can relate to the spirit of his ancestors. The key to these relations with the past is the soul. Pound borrowed from a lot of different sources to derive his own theories on the human soul. He used Cicero’s idea of the "immortality of the soul" in De Senectute (Longenbach 222-23).He also borrowed from Plato and the Phaedrus in the Spirit of Romance: "And this is the recollection of those things which our souls saw when in company with God-when looking down from above on that which we now call being, and upward toward the true being" (140-41). Pound himself claimed to have had two experiences with retrocognition which were extremely important to him. As Longenbach writes, "Pound’s poetic goal was the cultivation of ‘adventures,’ the soul’s visionary memories of the paradise or the past it once knew" (229).Pound recounts his own experiences with retrocognition in an essay on Arnold Dolmetsch published in 1914. "So I had two sets of adventures. First, I perceived a sound which was undoubtedly derived from the Gods, and then I found myself in a reconstructed century- in a century of music, back before Mozart or Purcell, listening to clear music, to tones clear as brown amber" (Eliot 433). Pound was drawing on or participating in what he determined to be the soul’s eternal memory. His essay begins with a description of his first adventure:

I have seen the God Pan and it was in this manner: I heard a bewildering and pervasive music moving from precision to precision within itself. Then I heard a different music, hollow and laughing. Then I looked up and saw two eyes like the eyes of a wood- creature peering at me over a brown tube of wood. Then someone said: Yes, once I was playing a fiddle in the forest and I walked into a wasps’ nest. Comparing these things with what I can read of the Earliest and best authenticated appearances of Pan, I can but conclude that they relate to similar experiences. It is true that I found myself later in a room covered with pictures of what we now call ancient instruments, and that when I picked up the brown tube of wood I found that it had ivory rings upon it. And no proper reed has ivory rings on it, by nature. . . .Our only measure of truth is, however, our own perception of truth. The undeniable tradition of metamorphoses teaches us that things do not remain always the same. They become other things by swift and unanalysable process (Eliot 431).

Pound’s own understanding of truth and what he perceived to be his reality are bold advancements from what was presented in the original An Adventure. The visionary’s experience becomes the sole measure of reality and therefore Pound’s encounter with Dolmetsch as Pan becomes factual. In his essay, "Psychology and Troubadours," Pound draws a parallel between himself and early visionaries who had no way of differentiating imaginary visions from a "real" environment: "These things are for them real" (Spirit of Romance 93). Also, although Pound’s adventures and experiences cannot technically be affirmed in any way, they "stand in a long tradition of similar experiences recorded in the literature of folklore, mythology, and the occult" (Longenbach 230). In the essay on Dolmetsch, Pound works to place himself in this tradition when he writes: "When any man is able, by a pattern of notes or by an arrangement of planes or colours, to throw us back into the age of truth, everyone who has been cast back into that age of truth for one instant gives honour to the spell which has worked, to the witch-work or the art-work, or whatever you like to call it" (Eliot 432). Like Moberly and Jourdain, who had peered into the past and subsequently took ten years to write about it, Pound was wrestling with putting his visions into poetry. The "arrangement of planes or colours," the "art-work" which "throws us back into the age of truth" is what Pound wanted to create with the early Cantos. Pound began writing the first of the Cantos around 1910 but did not pursue them in earnest until 1915. It was during this time that Pound is documented in his letters as having read Robert Browning’s poem "Sordello" out loud to Yeats at Stone Cottage. Although Pound had read the poem before, it was not until he read it to Yeats that "Sordello" became a major influence. He praises the poem in a letter to his father on December 18, 1915: "It is probably the greatest poem in English. Certainly the best long poem since Chaucer. You’ll have to read it sometime as my big long endless poem that I am now struggling with starts out with a barrel full of allusions to ‘Sordello’" (Bornstein 119-20). However, the original support Pound relied on from Browning would soon be replaced with occult references. In the June, July and August 1917 edition of Poetry Magazine, Pound published his Three Cantos. These three were supposed to be the beginning of his existing long work The Cantos. Even after the highly positive review of Browning’s poem to his father, Pound would have nothing to do with Browning’s style. The original opening, which served more or less as a dialogue with Browning, is deceiving. Pound makes no effort to sustain Browning’s technique through his poem. It does not function in a lyric mode, rather it is an "apologia for the lyric mood" (Nassar 12). Pound began to question Browning’s elaborate metaphor for the stage and his character’s acting on it. Pound did not hide his "aesthetic and philosophic problems" (Nassar 13) that he had with Browning when he wrote:

. . . what were the use

Of setting figures up and breathing life upon them,

Were’t not our life, your life, my life extended?

I walk Verona. (I am here in England.)

I see Can Grande. (Can see whom you will.)

You had one whole man?

And I have many fragments, less worth? Less worth?

Ah, had you quit my age, quit such a beastly age and

cantankerous age?

You had some basis, had some set belief (Poetry, June 1917, 115).

As if to answer his own question, and provide Browning with proper examples, Pound continued with passages in the mode of An Adventure. The only way to contain the "beastly and cantankerous age" in which one lived was to tap into the past as Moberly and Jordain had done.

Sweet lie!-Was I there truly? . . .

Let’s believe it . . .

No, take it all for lies

I have but smelt this life, a wiff of it-

. . . And shall I claim;

Confuse my own phantastikon,

Or say the filmy shell that circumscribes me

Contains the actual sun;

confuse the thing I see

With actual gods behind me?

Are they gods behind me?

How many worlds we have! If Botticelli

Brings her ashore on that great cockle-shell-

His Venus (Simonetta?),

And Spring and Aufidus fill the air

With their clear outlined blossoms?

World enough.

(Poetry, June 1917, 120-21)

Eugene Nassar claims that Pound demonstrated the "mind circumscribed by its diaphanous film-its limits-[which] imagines gods when in the presence of beauty . . . The mind as ‘phantastikon’ may be intuiting transcendent truths" (12). Pound wrestled with the "truth" about his occult link to the past in his revisions on Three Cantos all the way up until its republication in 1925. The once long opening addressed to Browning was reduced to the opening four lines of Canto II:

Hang it all, Robert Browning, There can be but the one Sordello. But Sordello and my Sordello? Lo Sordels si fo di Mantovana" (6).

Following the address to Browning, Pound presents his vision of his characters or in this case "Ghosts" that "move about me / Patched with histories" (Poetry 116). There is no need for Pound to go "setting up figures and breathing life into them" because his characters were already part of a living past. Pound’s "fragments" are in fact not "less worth" because together they form a more complete whole than Browning’s characters. Pound sees these apparitions hovering over the water at Lake Garda. As with his Imagist poetry, these early portions of the Cantos reflect Pound’s attention to presenting the clearest possible picture of his experience:

And the place is full of spirits.

Not lemures, not dark and shadowy ghosts,

But the ancient living, wood white,

Smooth as the inner bark, and firm of aspect,

And all agleam with colors-no, not agleam,

But colored like the lake and like the olive leaves (Poetry June 1917, 116).

Pound used specific people and places, such as Lake Garda, to set up a desired historical backdrop. Often with Pound, the more oblique source was championed. The names are obscure and esoteric, leaving "ordinary people" in the dark just as Pound intended. Pound’s references to antiquated places, his use of foreign language, all in addition to his occult content, contribute to a higher level of difficulty in his poetry:

‘Tis the first light-not half light-Panisks

And oak-girls and the Maenads

Have all the wood. Our olive Sirmio

Lies in its burnished mirror, and the Mounts Balde and Riva

Are alive with song, and all the leaves are full of voices (Poetry June 1917,118).

The visionary experiences that Pound recreates in the Three Cantos are matched with these areas to "emphasize their origin in the meeting of a particular consciousness with a particular place" (Longenbach 232). This association was a technique that Pound had already begun experimenting with in some of his writing such as "Provincia Deserta." Yeats put it into his own words in a portion of his prose piece Per Amica Silentia Lunae: "Spiritism . . . will have it that we may see at certain roads and in certain houses old murders acted over again, and in certain fields dead huntsmen riding with horse and hound, or in ancient armies fighting above bones or ashes" (354). The spirits that haunt Pound’s Cantos are ones which he spent much time excavating from history during his reading at Stone Cottage. Also, Pound used specific names and places from his research to create a sense of locality. In the first Canto it was places such as Sirmio, and in the second there were others such as the Dordogne valley in France:

So the murk opens.

Dordogne! When I was there,

There came a centaur, spying the land,

And there were nymphs behind him.

Or going on the road by Salisbury

Procession on procession-

For that road was full of peoples,

Ancient in various days, long years between them.

Ply over ply of life still wraps the earth here.

Catch at Dordoigne (Poetry July 1917, 182).

At the same time that Pound was struggling with the original Three Cantos, Yeats was preparing his own take on An Adventure. The older poet was busy formulating what he called the "doctrine of the mask" (Autobiography 102). According to Yeats, this doctrine "which has convinced [him] that every passionate man . . . is, as it were, linked with another age, historical or imaginary, where alone he finds images that rouse his energy" (Autobiography 102). Yeats’s link to the past came in a voice which he claimed to have heard for awhile but ignored. The voice even provided him with information leading to its identity. Yeats discovered that he was communicating with a Cordovan Moor named Leo Africanus. However, he did not take Leo seriously until a seance conducted on July 20, 1915. After the seance, Yeats began to consider the possibility of an anti-self existing from another period of time. Communication with this opposite personality would lead to a more complete existence as well as a better understanding of the self. Yeats began writing letters to Leo and in turn would write letters back to himself believing that Leo’s intentions could be conveyed through him. Now that Yeat’s theory had advanced to a stage where his opposite existed in another century, his idea advanced from one that was grounded in psychology to a theory that had just as much to do with history (Longenbach 190-91). There is no documented proof of Pound ever participating in one of Yeats’s seances. Despite Pound’s lack of involvement, it is impossible to overlook the parallels between the two poets work at the time. Pound was using his own ghosts and their historical associations in his early Cantos. In his final winter at Stone Cottage, Pound took interest in the seventeenth-century Neo-Platonic occult philosopher John Heydon. In 1662, Heydon published his Holy Guide. Although Pound enthusiastically read Heydon’s book, he presented a mixed image of him with Heydon’s debut in the original Three Cantos . In the final version of the original Three Cantos III, Pound introduces Heydon in a fashion that is somewhere between mockery and praise:

Another’s a half-cracked fellow-John Heydon,

Worker of miracles, dealer in levitation,

In thoughts upon pure form, in alchemy,

Seer of pretty visions (‘servant of God and secretary of nature’);

Full of a plaintive charm, like Botticelli’s,

With half-transparent forms, lacking the vigor of gods. . .

Take the old way, say I met John Heydon,

Sought out the place,

Lay on the bank, was ‘plunged deep in the swevyn;’

And saw the company-Layamon, Chaucer-

Pass each his appropriate robes; (Poetry Aug, 1917, 248)

Walter Bauman refers to Heydon as Pound’s "spiritual brother" (314). Despite the not-so flattering introduction of Heydon, Pound would appear to agree with Bauman. One possible explanation for Pound’s harsher opening remarks on Heydon could be that many people of Heydon’s own time did not think highly of his work. To many, Heydon was simply "a charlatan trifling with occult lore" (Bauman 306). In any case, Pound seems to make a point of acknowledging Heydon’s uncertain past before citing him as a credible source. Pound begins to spell out exactly what one could obtain by reading Heydon in a section of his prose piece Gaudier-Brzeska: A Memoir. In section 16, Pound writes positively about artists like Brzeska, Wyndham Lewis and Jacob Epstein who were on the forefront of the new movement Vorticism. Here he discusses the power a work of art can have:

A clavicord or a statue or a poem, wrought out of ages of knowledge, out of fine perception and skill, that some other man, that a hundred other men, in moments of weariness can wake beautiful sound with little effort, that they can be carried out of the realm of annoyance into the realm of truth, into the world unchanging, the world of fine animal life, the world of pure form. And John Heydon, long before our present day theorists, had written of the joys of pure form . . . inorganic, geometrical form, in his "Holy Guide" (157).

Pound also closes the section with a final reminder to read "John Heydon’s ‘Holy Guide’ for numerous remarks on pure form and the delights thereof" (Gaudier-Brzeska: A Memoir 167). There are several facets of the occult found in Pound’s memoir. He infers that the perfect work of art is layered with history. It is hundreds of years and hundreds of men in the making. The "realm of truth" is reached when the mind, as Nassar previously described it, has the ability to imagine "gods when in the presence of beauty." The "transcendent truths," that are a conglomeration of the past, can then be tapped as a source for the pure form Pound is describing (Nassar 12).Much of Pound’s desire for a pure truth goes hand in hand with his quest to be close to the Divine and obtain his "priest-like status." His use of Heydon becomes clearer as one reads that Heydon pondered questions such as "if God would give you leave and power to ascend to those high places, I meane to these heavenly thoughts and studies (Heydon 26). Pound borrows almost verbatim from Heydon and then cites him in "Canto 91":

to ascend those high places

wrote Heydon

stirring and changeable

‘light fighting for speed’ (76).

Heydon continues stating that people involved with studies such as his should realize that "their riches ought to be imployed in their own service, that is, to win Wisdome" (31). This "Wisdome" was something Pound wanted to make certain the masses or the "ordinary people" would not be privy to. It was exactly the divine wisdom, or gnosis, that Pound was in search of. Pound was asking the same questions and desiring the same answers that Heydon was asking hundreds of years earlier: "let us know first, that the minde of man being come from that high City of Heaven" (33). With these overt connections to Heydon, Pound’s opening remarks on him as a "half-cracked fellow" remain puzzling. Again, it is likely that Pound was initially shy about such overt references to a less-than-favorable occultist just as he was with some of Yeats’s mysticism. As it turns out, the title "Secretary of Nature" was actually Heydon’s and was printed on the title page of Holy Guide. Pound was respectful enough to include the title. Also in the Cantos, Heydon is in the company of men such as Ocellus, Erigena, Mencius and Apollonius. Pound appears to have thought much higher of Heydon than his opening remarks lead a reader to believe. In total, over half a dozen quotes are taken from Heydon’s work adding to the "crystal clear" quality of Pound’s Cantos (Davie 224).

From the green deep

he saw it,

in the green deep of an eye:

Crystal waves weaving together toward the gt/healing

Light compenetrans of the spirits

The Princess Ra-Set has climbed

to the great knees of stone,

She enters protection,

the great cloud is about her,

She has entered the protection of crystal . . .

Light & the flowing crystal

never gin in cut glass had such clarity

That Drake saw the splendour and wreckage

in that clarity

Gods moving in crystal

(Canto 91, 611)

In this selection, the "Pricess Ra-Set" has completed a journey that has allowed a metamorphosis to take place about her. The crystal which has encompassed her represents Heydon’s "pure form" that Pound was himself searching for. Inside this crystal protection "gods are manifest, whatever their ontological status outside" (Nassar 110). Pound’s metaphor shows up in several places. In "Canto 92," Pound describes "a great river" with the "ghosts dipping in crystal" (619). Also, in "Canto 91," Pound wrote:

"Ghosts dip in crystal,

adorned"

. . . A lost kind of experience?

scarcely,

Queen Cytherea,

che ‘l terzo ciel movete

[who give motion to the third heaven]

Pound already knew the answer to his own question about experience when he asked it. Crystal was chosen not only for its clarity to represent the pureness of form but it is hard and durable as well. The experience was not lost in the protection of this divine state that is the "crystal."

There are several individuals who were contemporaries of Pound that had a large influences on Pound and exposed him to their own ideas about the occult. People such as Yeats, A. R. Orage, Allen Upward, Dorothy Shakespear, and Olivia Shakespear all had their own occult interests. However, the largest occult influence on Pound, even greater than that of Yeats, was G. R. S. Mead. Mead became a member of Madame Blavatsky’s Theosophical Society in 1884. In 1889 he was Blavatsky’s private secretary and kept that position until her death in 1891. He served as the society’s editor for their monthly magazine but branched off and quit the society altogether in 1909. Blavatsky’s writings and practices aligned themselves more with the "pseudo-sciences" that Pound would not have approved of. Oddly enough, in Mead’s essay "‘The Quest’ - Old and New:

Retrospect and Prospect," he apparently does approve of Blavatsky’s ways either:I had never, even while a member, preached the Mahatma - gospel of H. P. B. [Blavatsky], or propagandized Neo-theosophy and its revelations. I had believed that "theosophy" proper meant the wisdom-element in the great religions and philosophies of the world (The Quest 296-97).

This passage represents thinking that was in line with Pound’s ideas on gnosis and his own pursuit of wisdom. Mead is considered by some to be "the best scholar the Theosophical Society ever produced" (Godwin 245).Pound’s assessment of what he experienced in his visionary episodes as well as his readings was heavily influenced by the writings and teachings of Mead. Pound met him at one of Yeats’s "Monday Evenings" at 18 Woburn Building in London which Mead regularly attended. On October 21, 1911, Pound wrote to his parents: "I’ve met and enjoyed Mead, who’s done so much research on primitive mysticism - that I’ve written you at least four times." [1] In another letter to his parents dated February 12, 1912, Pound praises Mead writing: "G. R. S. Mead is about as interesting - along his own line - as anyone I meet"(Beinecke 238). In a letter to his mother dated September 17, 1911, Pound relays that Mead had asked him to write a publishable lecture. Pound discusses the task with his more skeptical side of the occult: "I have spent the evening with G. R. S. Mead, edtr. of The Quest, who wants me to throw a lecture for his society which he can afterwards print. ‘Troubadour Psychology,’ whatever the dooce that is" (Beinecke 223). Pound did go on to give the lecture which gave birth to his essay "Psychology and the Troubadours." In this essay Pound wrote that "Greek myth arose when someone having passed through delightful psychic experience tried to communicate it to others" (92). Again Pound was referring to an occult "adventure" similar to that of Moberly and Jourdain. Once an individual has undergone this event "the resulting symbol is perfectly clear and intelligible" (Longenbach 91). Pound also endeavors to explain further his idea of the Greek "phantastikon." According to Pound, "the consciousness of some seems to rest, or to have its center more properly, in what the Greek psychologists called the phantastikon. Their minds are, that is, circumvolved about them like soap-bubbles reflecting sundry patches of the macrocosmos" (92). In April of 1913, Pound wrote a letter to Harriet Monroe attempting to clarify this element of his essay: "It is what Imagination really meant before the term was debased presumably by the Miltonists, tho’ probably before them. It has to do with the seeing of visions."

Pound’s phantastikon became his link to tapping into the purest form of "real symbolism." Dorothy Shakespear requested that Pound explain to her the difference between this symbolism and aesthetic or literary symbolism. He wrote her stating:

There’s a dictionary of symbols, but I think it immoral. I mean that I think a superficial acquaintance with the sort of shallow, conventional, or attributed meaning of a lot of symbols weakens - damnably, the power of receiving an energized symbol. I mean a symbol appearing in a vision has a certain richness and power of energizing joy - whereas if the supposed meaning of the symbol is familiar it has no more force, or interest of power of suggestion than any other word, or than a synonym in some other language (Pound/Shakespear 302).

Of course, the ability to perceive these symbols was not within the reach of everyone. It was only for those who have set sail in the pursuit of higher wisdom. Those in pursuit of gnosis "possess the key to the mysteries of its symbolism and establish themselves as priests - divinely inspired interpreters to whom the uninitiated public must turn for knowledge" (Longenbach 91). From here, the possibilities are endless according to Pound:

"All is within us", purgatory and hell,

Seeds full of will, the white of the inner bark

the rich and the smooth colours,

the foreknowledge of trees,

sense of the blade in seed, to each its pattern.

Germinal, active, latent, full of will,

Later to leap and soar,

willess, serene,

Oh one could change it easy enough in talk.

And no one vision will suit all of us.

Say I have sat then, the low point of the cone,

hollow and reaching out beyond the stars,

reaches and depth, the massive parapets,

Walls whereon chariots went by four abreast (Longenbach 237).

Pound made it a habit to not only read Mead’s article’s and books but he also religiously attended his lectures outside the "Monday Evenings." In another letter to his parents he wrote: "I’m going out to Mead’s lecture. And so on as usual. This being Tuesday" (Beinecke 271). From these readings and lectures, Pound most likely got his inspiration for the beginning of his revised Cantos:

the passing into the realms of the dead, while living, refers to the initiation of the soul of the candidate into the states of after- death consciousness, while his body was left in a trance. The successful passing through these states of consciousness removed the fear of death, by giving the candidate an all sufficing proof of the immortality of the soul and of its consanguinity with the gods (Taylor 319).

The "initiation" process of the soul was one that Pound decided must begin his entire Cantos. "Canto 1" starts with: "And then went down . . ." which initiates a descent that is the beginning of this journey (3). Pound made it clear in "Canto 1" that the Odysseus figure was alive during his descent just as Mead required the figure to be "living." Also, in a blatant attempt to achieve the "consanguinity with the gods," Pound’s character drank the blood of the sheep that was sacrificed to them.

The process that Pound is discussing is palingenesis, or the birth and the growth of the soul. The ultimate goal of the entire process, as Pound saw it, was "the expansion of the initiand’s consciousness into a state where he awakes to his relationship with the gods, and participates in their world" (Celestial Tradition 107). At this initial stage the initiate knows nothing except that he is on a quest for gnosis. As Pound wrote in Canto 47: "Knowledge the shade of a shade, / Yet must thou sail after knowledge / Knowing less than drugged beasts" (30).

The completion of the journey is the passage into what was previously described as "the crystal." This stage is the graduation from the ephemeral world of man to the realm of the gods. The soul has passed "from fire" of the "Kimmerian lands" of "Canto 1" "to crystal / via the body of light" (Canto 91,61). Pound put it much more bluntly when he stated that one must "bust thru" to this realm of understanding but he made his point (Celestial Tradition 107). Although he makes references to the exceptions, Tryphonopoulos contends that "Scholarly comment on Pound’s relation to the occult is virtually nonexistent" ("Occult Education" 75). The difficulty in analyzing Pound’s occult studies is that his reading and influences are so vast. From his amassed material Pound would piece together a detailed mosaic. This method provided a coherence for his presentation. In this fashion, structure begins to surface in even his most dense work The Cantos. Tryphonopoulos understands The Cantos to be a "collection of fragments gathered according to a predetermined plan for the purpose of validating the author’s original value system" (1). Pound seems to be speaking of this in the very late "Canto 110" when he writes: "From times wreckage shored / these fragments shored against ruin" (781). These elements pulled from the rubble of history and which Pound tiles together are what make the picture complete.

J’ai dans ma bibliothèque quelques livres de grammaire et de langue française (chinés dans les vide-greniers) dans un état qui laisse supposer qu’ils ont été fréquemment pris en main. Par exemple, celui-ci, dont la trente et unième édition (!) fut imprimée en 1950. C’est un manuel de grammaire destiné aux classes de sixième. La deuxième leçon présente, dans la rubrique La vie des mots, le texte suivant : « Le sens des mots s’élargit : Le mot boucher désignait au Moyen-Age l’homme qui vendait de la viande de bouc. Un panier n’était proprement qu’une corbeille à pain. Le mot bureau a désigné tout d’abord un petit morceau de bure ou étoffe grossière, ensuite le meuble sur lequel on pose cette bure, puis la salle dans laquelle ce meuble est placé… »

J’ai dans ma bibliothèque quelques livres de grammaire et de langue française (chinés dans les vide-greniers) dans un état qui laisse supposer qu’ils ont été fréquemment pris en main. Par exemple, celui-ci, dont la trente et unième édition (!) fut imprimée en 1950. C’est un manuel de grammaire destiné aux classes de sixième. La deuxième leçon présente, dans la rubrique La vie des mots, le texte suivant : « Le sens des mots s’élargit : Le mot boucher désignait au Moyen-Age l’homme qui vendait de la viande de bouc. Un panier n’était proprement qu’une corbeille à pain. Le mot bureau a désigné tout d’abord un petit morceau de bure ou étoffe grossière, ensuite le meuble sur lequel on pose cette bure, puis la salle dans laquelle ce meuble est placé… »

La langue, l’écriture, l’expression, la communication

La langue, l’écriture, l’expression, la communication

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

D’abord, il est indispensable de faire justice à une illusion. Un coup de sonde dans les quarante dernières années suffit pour cela. En quoi l’enseignement du latin et du grec a-t-il pu contribuer en quoi que ce soit à l’approfondissement de la culture, sinon à sa défense ? Les élèves qui sont passés par cette étape scolaire, certes en soi passionnante, ne se sont pas singularisés dans la critique d’une modernité qui se présente comme une guillotine de l’intelligence. Ils ont suivi le mouvement. Il est presque normal que ce pôle d’excellence ait été emporté, comme tout le reste, par la cataracte de néant qui ensevelit notre civilisation. Il aurait pu servir de môle de résistance, mais il aurait fallu que la classe moyenne fût d’une autre trempe. Car est-il est utile aussi d’évoquer les professeurs de latin et de grec qui, sauf exceptions (soyons juste) ne sont pas différents des autres enseignants ? Ils possèdent, comme chacun, leur petit pré carré, leurs us et coutumes, leurs intérêts, et, généralement, partagent les mêmes illusions politiquement correctes, ainsi qu’un penchant à profiter (comme tout le monde, soyons juste !) de la société de consommation. Faire des thèmes et des versions contribue à renforcer la maîtrise intellectuelle et langagière, certes, mais cela suffit-il à la pensée ? Ne se référer par exemple qu’à la démocratie athénienne, pour autant qu’elle soit comprise de façon adéquate, ce qui n’est pas certain dans le contexte mensonger de l’éducation qui est la nôtre, c’est faire fi de Sparte (victorieuse de la cité de Périclès), de l’opinion de quasi tous les penseurs antiques, qui ont méprisé la démocratie, de l’idéologie monarchique, apportée par Alexandre et les diadoques, consolidée par le stoïcisme et le néoplatonisme, et qui a perduré jusqu’aux temps modernes. Il faut être honnête intellectuellement, ou faire de l’idéologie. De même, la Grèce et la Rome qu’ont imaginées les professeurs du XIX

D’abord, il est indispensable de faire justice à une illusion. Un coup de sonde dans les quarante dernières années suffit pour cela. En quoi l’enseignement du latin et du grec a-t-il pu contribuer en quoi que ce soit à l’approfondissement de la culture, sinon à sa défense ? Les élèves qui sont passés par cette étape scolaire, certes en soi passionnante, ne se sont pas singularisés dans la critique d’une modernité qui se présente comme une guillotine de l’intelligence. Ils ont suivi le mouvement. Il est presque normal que ce pôle d’excellence ait été emporté, comme tout le reste, par la cataracte de néant qui ensevelit notre civilisation. Il aurait pu servir de môle de résistance, mais il aurait fallu que la classe moyenne fût d’une autre trempe. Car est-il est utile aussi d’évoquer les professeurs de latin et de grec qui, sauf exceptions (soyons juste) ne sont pas différents des autres enseignants ? Ils possèdent, comme chacun, leur petit pré carré, leurs us et coutumes, leurs intérêts, et, généralement, partagent les mêmes illusions politiquement correctes, ainsi qu’un penchant à profiter (comme tout le monde, soyons juste !) de la société de consommation. Faire des thèmes et des versions contribue à renforcer la maîtrise intellectuelle et langagière, certes, mais cela suffit-il à la pensée ? Ne se référer par exemple qu’à la démocratie athénienne, pour autant qu’elle soit comprise de façon adéquate, ce qui n’est pas certain dans le contexte mensonger de l’éducation qui est la nôtre, c’est faire fi de Sparte (victorieuse de la cité de Périclès), de l’opinion de quasi tous les penseurs antiques, qui ont méprisé la démocratie, de l’idéologie monarchique, apportée par Alexandre et les diadoques, consolidée par le stoïcisme et le néoplatonisme, et qui a perduré jusqu’aux temps modernes. Il faut être honnête intellectuellement, ou faire de l’idéologie. De même, la Grèce et la Rome qu’ont imaginées les professeurs du XIX