Visions of China: The Nationalist Spirit in Chinese Political Cinema

Michael Presley

Ex: http://peopleofshambhala.com

What follows is an introduction, with examples, of a particular sub-set of Chinese cinema, namely film as overt political propaganda. Here, the distinction is one between China and Chinese considered as an organic national unit, opposed to two enemies: first, their historical and overtly hostile enemy, Japan; and second, a covert foreign cultural and economic influence, Occidental-style liberal capitalism. The films discussed are political inasmuch as they uncover a distinctly political ground; a ground most acutely expressed within the work of German political theorist Carl Schmitt’s The Concept of the Political (1927-1932). For Schmitt, the political is strictly defined by the disjunction between a people and their existential enemy, a distinction that supersedes all other social or cultural considerations. Without going into the historical precedent for the existence of Japan as China’s enemy, or considering whether within an objective historical context the Japanese are necessarily worthy of being their enemy, we will simply accept the fact that it is so. Alternately, the political enemy defined by Western influence is less understood, and often less immediately recognized, in spite of its likely more subversive and on-going quality.

We recognize that at the present time in world history the West is thoroughly dominant, although for how long it will remain so is an open question. However, because of its cultural, economic and military dominance, there is no current Western analog we can cite that sufficiently compares to the current Sino-Japanese relationship. This is so in spite of certain efforts to invoke a subset of Islam (under the common name Al-Qaeda), and lately Russia, as the Western enemy. The former is at most a loose association whose presence is often not very definable as a concrete geopolitical entity, whereas Russia, unlike the former Soviet Union, takes the form more of a competitor showing certain social, political and economic interests that run afoul of the modern Western liberal agenda. For its part, China has, at times, been considered an enemy, however this concept is difficult to square with the fact that Western capital has made China its manufacturing base, and in a symbiotic relation China has financed much of the West’s debt-backed monetary system.

Nevertheless, it would be wrong to conclude that Western liberalism has no mortal enemy, because in a real sense its enemy is none other than an historical, anti-liberal, pre-modern indigenous tradition. We trace this movement away from a more traditional non-liberal Occidental form, first in Thomas Hobbes’ political theory, and, broadly speaking, even earlier within an epistemological nominalism found within certain strains of late medieval scholastic philosophy—thinking which ultimately led to philosophical Idealism, along with a related strain of empirical skepticism and a beginning scientism derived from Descartes’ personalist methodology. By the time of the Enlightenment, the liberal deed was done and the die cast. Tradition, from then on, was no longer an option for anyone.

In our present context, that is, politically oriented cinematic expression, we cannot be surprised to find tradition mostly deprecated within American popular cinema, inasmuch as America is a child of the Enlightenment. Likewise, it cannot be denied that Hollywood remains the most influential cinematic product, worldwide. In spite of an indigenous Chinese film industry, Avatar is the highest grossing film in China. At the same time we note that the number three and number five mainland money-makers are adaptations of a Chinese classic novel (The Journey to the West). Shorn of special effects, Hollywood cannot be said to dominate Chinese cinema, and a strong nationalistic spirit manifests among Chinese movie-goers. Whatever the case, the future development of Chinese cinema is likely not to follow a derived Hollywood script.

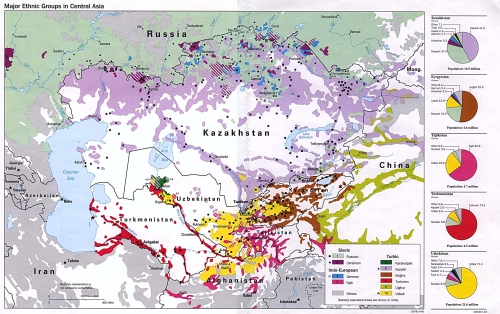

It is wrong to view China through an Occidental liberal lens. As a non-liberal ethnostate we must understand that China’s geopolitical actions are less directed toward exporting its own peculiar political-economic system (a system officially known as Socialism with Chinese Characteristics) in hopes that others might emulate it, than it is in preserving and protecting what the regime believes to be its own indigenous ethnic and racial prerogatives within internal contiguous borders (to include Tibet and the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region), and externally by way of exploiting developmentally challenged areas such as Africa. In the latter, unlike the liberal Western agenda’s foreign policy, Chinese are not interested in turning Africans into Chinese, but rather are they concerned with a more long-term strategic position. If this can be done by leaving Africans to be Africans, that is fine, and in fact it is preferred. The West, on the other hand, is intent upon turning Africans into liberal Westerners, a naïve and ultimately futile project given the ethnic and tribal instincts of Africans. Chinese, who are also ethnic, tribal, and non-liberal seem to have a better intrinsic understanding of the situation.

Considering our topic proper, we must recognize that the Hollywood product is no more than loosely disguised political and social propaganda, albeit quite subtle compared to either “old-style” Soviet or National Socialist propaganda [think Sergei Eisenstein and Leni Riefenstahl]. Ironically, out-in-the-open political propaganda is much less insidious than the subtler variety typically found within Western movies, simply because overt propagandistic displays are easier to recognize, and possibly discount. No one likes to be fooled or manipulated. To this end, in two of the films we will consider, overt propagandizing in effect diminishes any higher aesthetic value they may possess. Also, we should always remember that any ubiquitous media, our “external environment,” conditions us in ways that are often subtle, and unrecognized. We may consider the words of Canadian English professor, Marshall McLuhan [the introduction to The Mechanical Bride], for some guidance:

[This] book… makes few attempts to attack the very considerable currents and pressures set up around us today by the mechanical agencies of the press, radio, movies, and advertising. It does attempt to set the reader at the centre of the revolving picture created by these affairs where he may observe the action that is in progress and in which everybody is involved. From the analysis of that action, it is hoped, many individual strategies may suggest themselves.

Thus, by observing certain cinematic forms—an analysis of action, perhaps we may profit as we attempt to understand and ameliorate a profound Western decadence, and spiritual deracination that too often manifests among our indigenous population. Questions we may confront along the way: is a political solution available, even potentially; can a foreign sensibility show the way or offer guidance; and, if so, can cinematic art be an effective means to a political end?

To decide, we must consider the general status of politics in art. Within an aesthetic context, some believe that politics sullies the very notion of art. Here, art is taken as something sublime, and removed from the more vulgar aspects of Homo politicus. From the standpoint of what we might want to call high-art, a critique of political cinema requires us to ask whether such a thing can ever be more than an exercise in acknowledging a sort of low brow entertainment, an attempt to give the vulgar more due than is proper, and ultimately whether political art is even worth an aesthetic critique. That is to ask, can political propaganda ever be said to have an aesthetic value? Can it ever approach high art, or is it a perversion of the very notion of art? These questions can only be answered first by considering the nature of art in conjunction with the nature of man.

Actress Li Lili, country innocent Ling Ling, in Daybreak (left) and Zhou Huishen (Xiao Yun) and Zhao Xuan (Xiao Hong), in Street Angel (right).

Before beginning a discussion of art one ought to first set forth, or have already established, a groundwork of principles allowing a reference or a framework for subsequent valuation. Within popular art criticism, especially criticism pertaining to ubiquitous and common cinema (common in the sense that it is opposed to fine art), a ground is often not made very explicit. Maybe rightly so, since all leaving the cinema are critics; everyone has an opinion and anyone’s seems to be as good as any other. But do these matters turn on opinion, and in any case is there an inherent epistemological equality among opinions? We understand that it is not easy to formulate a groundwork for aesthetic valuation due to the generally recognized non-objective (at least in an empirical sense) nature of aesthetics, which leads some to argue that any conclusions must therefore be inconclusive and likely arbitrary. Others know differently, and want to base their critique within a progressive aesthetic hierarchy leading upward to an ideal, a transcendental conception of Beauty, whose being-nature supports the final end of man (in an Aristotelian teleological sense), and whose arbiter is generally believed to be the wisdom found in and flowing from tradition. Behind it all, aesthetic judgment is required. The first question, then, is how to judge? To simply state that aesthetics is the science of “the beautiful” solves nothing as we attempt to parse specific instances of art. Such a definition necessarily points beyond whatever can be contained within words, even though our words may lead us toward a rational understanding of art as the expression of the formal idea of Beauty, and as it uncovers a non-rational, non-discursive experience of the transcendental.

At the same time it is wrong to judge art wholly through its participation in, or as an expression of, an integral transcendental formal idea, simply because various practical aspects of a particular art may not be transcendental at all. Within the philosophy of art, as the historian of philosophy, Étienne Gilson, argued [see The Arts of the Beautiful], art’s most fundamental aspect is a making. It is a human activity resulting in the creation of artifacts. And as a directed activity it is intentional. The resulting product may be produced for a variety of reasons, the least of which is intended to express any transcendental idea of Beauty. For instance: art may be intended to evoke a certain emotion; it may be made for decoration; a therapeutic value might be supposed; or perhaps the goal is simple entertainment with no other implied motive; for advertising; or, as in our current subject, overt political influence. The list is not exhaustive. The ability of an art-form to meet the criteria of more mundane purposes does not in any way depend upon the artwork being representative of an ideal, however this fact does not necessarily exclude its participation in the ideal, nor can we always casually dismiss art that is not made in order to represent or evoke a transcendental theme.

Turning to political art we should keep in mind that its place in Western tradition (derived as it is from classical philosophy) always understood that man cannot fulfill his natural end outside the social order, and because of it the polity or state has traditionally been understood to exist prior to the individual. Thus, the arts of the political (that is, political endeavors in their fullest meaning) are inseparable from the nature of man, and art-forms depicting political arts must correspondingly hold a valued place in any discussion of art as art. The degree to which examples of political art achieve their goal, that is, as an expression of the political as a concrete instance of an ideal, can be used as a criteria to establish an ordinal aesthetic hierarchy. It is not the purpose of this review to rank the films discussed, but rather to simply highlight some examples of the genre. At the same time, each in their own way could be ranked high, from a political standpoint. We are not here referencing acting, cinematography, special effects, and all the rest, but rather the film’s expression of the political.

Cinema should be a primary vehicle of political expression. Cinema holds a unique position among the arts inasmuch as it participates in formal aspects of the several isolated pre-cinematic art forms. Cinema shows movement as does dance. Cinema offers up spoken word as does rhetoric, poetry, and song. It may describe color, and juxtaposition of form as in painting. Perhaps more importantly film abstracts both the comedic and tragic from traditional theater. This multiform aspect may be why cinema has always been attractive to the political propagandist, and it is not incorrect to state that cinema, more than any other art form, exemplifies the Platonic hesitancy that denies unfettered music into the polity, but rather requires necessary censorship within the best of all states. Today in the liberal Occident, especially the United States, we do not always primarily think about a dangerous political aspect of cinema inasmuch as censorship is generally considered to be repugnant to the civic mind. Because of it, the state censor has been reduced to a vestigial, industry sponsored non-governmental review board (the Classification & Ratings Administration, or CARA) that no one knows anything about, nor does anyone particularly care. However, it is not so within more traditional societies, or in non-liberal regimes. In such regimes there are two chief considerations: first, and typically most important, the maintenance of the regime against subversive elements; and second, the idea that the regime ought to act as a moral agent in order to correct behavior and edify the citizenry. Contrary to modern-day Western political norms we should point out that the first above-cited notion may or may not be indicative of tyranny, but depends upon the motive and methods of the regime in question, while the second aspect is part and parcel of classical Western political theory stemming from Plato, along with Aristotle’s understanding of the state as logically prior to the individual. Here, the state is necessary in order for citizens to achieve their individual natural end. Needless to say, these considerations remain unpopular within modern political theory, in spite of some later efforts to recover lost ground, for instance in some of the work of Leo Strauss.

Political propaganda, whether cinematic or no, finds its most immediate subject matter in war. War is, after all, the ultimate existential crisis for a people, and, anent Carl Schmitt, the conflict between a nation and their enemy is said to define the concept of the political, altogether. As a contrast to China’s relation to Japan, Hollywood’s presentation of the Japanese question has changed considerably since the Second World War. Although Americans have rehabilitated Japanese, making them as a likeness unto their own image, it is not so from the standpoint of the Chinese toward the Japanese, where, across a small area of ocean, island-mainland cousins remain solid enemies. This East Asian political disjunction now becomes our starting point when considering Chinese political cinema.

Vignettes from The Classic for Girls.

Chinese political cinema began with a theme of disaffection. It was a disaffection over not only external forces (forces not always, or even primarily, Japanese), but internal social discontent associated with a turn from an agrarian feudal order, to a modern cosmopolitan state. Shanghai was a principal focal point as it represented the locus of both old and new. In assessing a not particularly arbitrary starting time, we consider the May Fourth (1919) Movement as a turning point. At the beginning of the last century China was in transition. An imperial dynastic tradition had fallen apart, while European colonialism carved up the coastal cities of China. The end of the First World War resulted in a Chinese sense of political betrayal inasmuch as whatever China could do for the Entente (mostly the Chinese Labor Corps) had been summarily discounted at Versailles. Japan came away the big winner on the Chinese mainland, and as a result an anti-Western sentiment grew, along with an established hatred for anything Japanese. But this resentment was two-edged. First, in spite of a sense of political betrayal, Chinese intellectuals understood that their only hope for cultural transformation [that is, liberalism as opposed to “the old ways”] was to appropriate both the West’s advanced technology and, as a foil to tradition, its ideology. However, it is one thing to make use of foreign technical knowledge, but quite another to appropriate foreign political thinking. A gun is a gun is a gun. Can the same be said for the social effects of Enlightenment derived political theory? And what happens when a culture encounters both, at the same time? One also senses that a growing Western influenced Chinese social decadence, associated in their own minds with the economic hegemony of what we now call globalist capitalism, was instinctively repellant to those steeped in a traditional Confucius-Taoist-Buddhist hierarchical folk culture. In fine, the May Fourth Movement contained a contradiction between liberalism (i.e., the universal rights of man) and nationalism (an organic understanding of what constitutes a nation), and early Chinese political cinema infused it all.

Before discussing specific films it is necessary to say a few words about the distinction between what follows and what most people may know as Chinese cinema. If they know it at all, Westerners are likely familiar with Chinese fantasy cinema. Here, women are portrayed as kung-fu masters, adept at swordplay and hand to hand fighting. They are merciless killers, able to climb walls effortlessly, and fly through the air. They can fight on willowy bamboo stalks. Sexuality may be implied, but is hardly ever explicit. Entertaining as they may be, characters such as those typically portrayed by Michelle Yeoh and Brigitte Lin have no place in early Chinese political cinema. In reality, women are not by nature physical fighters, but if made into fighters their weapons are usually sexuality coupled with cunning. Only in modern times, with the advent of killing at a distance, are women able to become warriors. By the time of the Chinese Civil War women were sometimes conscripted as soldiers, and women soldiers are portrayed in one of the films we will discuss. First we will give a brief synopsis of representative political films, and then offer some general comments, starting with three pre-communist films.

Daybreak [Tianmíng, 天明 1933, available at the Internet Archive with English subtitles] directed by Sun Yu, an American educated Chinese, tells the story of Ling Ling, a naïve country girl who, due to war, leaves her fishing village for Shanghai. Taking a position as a factory worker, Ling Ling is soon brutalized by the owner’s son, and falls into a life of prostitution. In spite of her fall, Ling Ling retains an essential dignity, and works her way up to a position of “high class” call-girl servicing rich clients. She becomes well to do as a result of her client’s largesse, using her earnings to help orphans. Ling Ling’s friend has become a political revolutionary, and in order to cover for him she allows herself to be arrested. The final scene before her firing squad is an appeal for the Chinese as a people to stop internecine conflict, and instead to focus their collective efforts on nationalism with the aim of defeating both the internal and the foreign enemy.

Another pre-revolutionary film, Nuer jing 女兒經 1934, highlights explicitly the May Fourth Movement’s contradiction. The movie’s title (in English known alternately as A Bible for Girls/The Classic for Girls, or sometimes Women’s Destiny) is taken from a Ming era (1368-1644) Confucian primer for young girls, the purpose being to establish a moral foundation and guidance within an established hierarchical social order. The Classic for Girls is rather long, about two and a half hours, and is available without translation at the Internet Archive. The action takes place within an upscale Shanghai apartment, where a group of young women stage a reunion, narrating their life stories over the past ten years, each story shown as a separate “movie within a movie” vignette. Due a particular moral or social failing exacerbated by fate, each woman succumbed to some or another tragedy. The implication is that in large part their problems were due to Western-style social decadence coupled to a personal moral failure. At the close of the film, the women are nevertheless upbeat, happily watching a street parade staged by the Sino-fascist New Life Movement, a KMT inspired anti-communist, anti-democratic, “neo-traditionalist” group incorporating a strain of Sino-Christianity by way of Soong Mei-ling’s influence [Generalissimo Chaing’s wife].

Street Angel [Malu tianshi, 马路天使 1937] directed by Yuan Muzhi, tells the story of two sisters, Xiao Hong (played by Zhou Xuan) and Xiao Yun (Zhao Huishen). Like Ling Ling in Daybreak, sisters have fled war only to be exploited by their adoptive parents. Xiao Yun is coerced into prostitution, while Xiao Hong is employed as a “sing song” girl, lately to be sold to a rich businessman/gangster. Rebellious sister Xiao Yun is stabbed by her adoptive father, and cannot be saved. A physician refuses to help; her poor friends have no money to pay him. In the end, there appears to be no way out for the characters within Shanghai society as it is.

After the Japanese surrender and the defeat of the KMT Nationalist Party, the Chinese Civil War ended with the creation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. An early Chinese Communist Party sponsored film, The White Haired Girl [Bai Mao Nu, 白毛女 1950] directed by Wang Bin and Shui Hua, tells the story of peasant girl Xi’er (Tian Hua) and her betrothed, Dachun (Li Baiwan). In order to satisfy Xi’er’s father’s land tax, the daughter is sold into slavery to the landlord, who proceeds to rape her. Pregnant, she escapes into the mountains suffering a miscarriage. The girl lives off the land taking shelter in a cave, but during the harsh winter her black hair turns white. In order to survive, at midnight Xi’er leaves her mountain abode, stealthily enters a Taoist shrine, and steals food placed by peasants as an offering to the local goddess. The frightened peasants spy her running in and out of the shrine, and create the legend of the “white haired goddess of the temple.” Shortly after Xi’er’s slavery, her betrothed runs away from the village and, out of grief along with a desire for political justice, enlists in the Communist Party Eighth Route Army which now, several years on, has liberated his village. Strangely intrigued by the peasant’s folk tale, Dachun sets a trap for the temple goddess who, of course, turns out to be his long lost love. Xi’er, with the help of the Red Army and peasants, captures the evil landlord, who is swiftly brought to justice.

Xi’er sold (left), Xi’er as Taoist goddess (center) and The ghost becomes human (right).

The Red Detachment of Women [Hongse niangzijun, 红色娘子军 1961, directed by Xie Jin] is more or less based on historical events. RDW is set during the Chinese Civil War (the so-called Agrarian Revolution years), 1927—1937. At the time represented in the movie, the Hainan island area was a fighting ground between KMT Nationalists, Japanese, and Chinese Communist guerrillas. In 1934 (some sources say 1931) the 2nd Women’s Independent Regiment of the Red Army was commissioned. Legend has it that over 100 women ran away from oppressive captivity, and joining peasants and workers helped form the force. It has been reported that during the Japanese occupation of Hainan over a third of the male Chinese population were killed. This practically necessitated that women be engaged in many non-traditional roles, not a problem since gender egalitarianism was an ostensible CCP ideal, at least as it pertained to the proletariat workers and peasants.

Xijuan Zhu plays peasant girl Wu Qinghua, who has escaped the slave dungeon of Nan Batian, the Southern Tyrant. The defiant Wu escaped before, so this time she’s chained up in anticipation of being sold to another master. After her final escape, and on the run, she meets disguised Red Army officer, Hong Chongqing, who directs her to the Red Army hideout. Once there she joins an all-woman’s detachment and successfully leads her regiment to victory over Nan and his running dogs.

In a more modern vein we consider two recent films, first Zhang Yimou’s Flowers of War [Jinling Shisan Chai, 金陵十三钗 2011]. Zhang Yimou is likely the best known Chinese director, responsible for many notable films such as Ju Dou, The Story of Qui Ju, Shanghai Triad, House of Flying Daggers, and Curse of the Golden Flower. Flowers of War is set in 1937 Nanking during the Japanese invasion. It is the story of an American posing as a Catholic priest, and his at first reluctant attempt to save a group of Chinese Catholic schoolgirls. The American’s fighting companions consist of a cynical band of prostitutes who have lately arrived from the ruins of a bombed out brothel, seeking shelter. In order to save the pure and innocent schoolgirls, these world weary prostitutes take the place of the schoolgirls. They cut their hair, don Catholic dress, and wrap their bodices with sharp glass shards that will be used as knives in order to cut the throats of their Japanese captors who are coming to take them away in order to use them as “comfort women”. Once the prostitutes are taken away by Japanese troops, the American escapes to safety with the Chinese Catholic girls.

Next we consider the Chinese adaptation of Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’ novel, Dangerous Liaisons [危險關係, 2012]. Directed by South Korean Hur Jinho, this Mandarin language Chinese movie is set in 1931 Shanghai. The decadence of the characters is certainly appalling; naïve character Du Fenyu (played by Zhang Ziyi) considers suicide, only finally understanding that Western decadence must give way to positive action; at the end of the film she leaves Shanghai, joining the Communists [one suspects that it is not the Nationalist KMT inspired New Life Movement that she joins, as portrayed in the film, National Customs, but one cannot be sure] in her new role as school teacher and, one suspects, Japanese fighter.

Peasant Wu, confronting her tormentor.

Finally, two examples of overt propaganda that completely strip the films of all aesthetic sensibility may be cited. First, Breaking With Old Ideas, and then, National Customs. The first was produced under the care of Jiang Qing [artistic director of the Cultural Revolution] as a “reminder” to all Chinese that revisionism must never be allowed to manifest in the era of “Mao Zedong Thought”. Yet, to take this film either as entertainment or edification would be to take it out of any possible context, and the contorted plot underscores just how spiritually stifling communism can be. National Customs is different, in that it actually aims at showing the contrasts between two social orders: traditional Chinese agrarian folkways, and modern Shanghai Western influence. However, due to the influence of KMT censors, the film turns into nothing more than a grotesque indoctrination session. This is really too bad inasmuch as National Customs highlights two ironies. First, it is the last movie featuring actress Ruan Lingyu before her suicide, and secondly, it is thoroughly anti-Western. The first is an irony inasmuch as Ruan’s character, Zhang Lan, espouses sentiments that would have prevented her from suicide had she paid attention. The second irony is that the KMT were entirely dependent upon Western support, and once that stopped the mainland fell to the CCP. Plus, Soong Mei-ling was hardly, in real life, the apotheosis of the young woman played by Ruan, but in outward appearance was more like the character Zhang Tao, played by Li Lili. [As an aside, for anyone interested in this era’s cinema, they can be directed to the movie, Center Stage, an excellent quasi-documentary about the life of Ruan Lingyu. It is available online with subtitles, for free.]

A common theme among the films is how those possessed of naïve apolitical innocence, or cynical immorality, can rise above their station given the proper influence. Proper influence is a correct political outlook conjoined to a nationalist spirit. The women in Daybreak, Street Angel, andDangerous Liaisons are, in a real sense, pre-political since they have not yet been introduced to, or have only recently been made aware of, a political solution that could ameliorate their depravity. In the later films, by the time Xi’er and Wu escape their immediate oppression, a political solution offers itself, and it only remains for them to embrace it. But, in return, before embracing a political solution they must to be willing to offer up their lives. One’s life is the necessary condition inherent within a true political context. The situation described by Flowers is much the same. Strictly speaking, political ideology is not the immediate issue for the women, much less the American. Nevertheless, the individual’s life must be judged as secondary to the hopeful existence of a greater nation-being which, for its part, must survive at all costs. Along with killing the enemy (although in this instance killing Japanese is a secondary problem for the women), their immediate concern is saving the next life-giving generation—Chinese school girls. Unlike Wu (Red Detachment of Women), these women are not professional soldiers, but civilians, and their planning against the enemy is ad hoc. In a similar rejection of Western modernity, Du Fenyu forsakes her ill-gotten gain (inherited from a dead spouse) in order to groom the next generation, and fight the Japanese army. It is a moral teaching, hearkening back to The Classic for Girls, and the book of the same name expounding moral instruction for girls and young women.

To conclude we should probably say a few words about religion. Religion is understandably downplayed within these revolutionary themes, just as overt Chinese tradition is deprecated in official Communist era films (The White Haired Girl and The Red Detachment of Women). This is not surprising, as the Communist Party takes the place of the church, and the transcendental spirit is transformed into the community of socialists. Strict Western-style political communism was never suited for China, though. Chinese have always been superstitious, and have always expressed authentic religious feeling. Consequently, Chinese art was always religious, featuring large doses of Buddhist ceremony and Taoist magic. To cite an example: in the historical Three Kingdom period [220-280 AD] Warlord Lui Bei’s chief advisor and general, Zhuge Liang, is depicted as a Taoist priest in Luo Guanzhong’s Romance of the Three Kingdoms. But Chinese Communism is slow to change. In spite of religious scenes in both The White Haired Girl and Flowers of War, religion is not a chief characteristic or influence upon any character’s heroic action. Rather, the chief influence is political—a nationalist spirit. The earlier film depicts traditional folk religion as simple superstition, and if anything it exists as a hindrance to the peasant’s acceptance of the clear light of Chinese Communism. In effect, the Eighth Route Army is responsible for debunking primitive religious superstition, and it is the army that is responsible for “reincarnating” Xi’er back into the world of the living.

For their part, both the Flowers and ersatz priest are out of place in the cathedral. But only at first. As the movie progresses it is almost as if a spirit descends upon the characters, and guides their thinking. But even that is not clear. And if it is an Occidental spirit, it is not the current liberally interpreted spirit of “turn the other cheek” Christianity, but rather an earlier Judaic tradition of destroying one’s enemies without mercy. For the Flowers, their humanity may simply be the blossom of an integral “Taoist yin” nature directed toward feminine nurture; coupled, no doubt, with both fear and intense hatred of Japanese soldiers. The American, in his role as a newly self-ordained priest, could have easily left on his own, saving his life and turning the rest over to Japanese invaders. In many respects his is the most enigmatic of characters, and his inclusion in the film, along with Chinese Catholic school girls, deserves further consideration.

Christian Bale, Western reprobate turned hero (top) and Zhang Ziyi as Du Fenyu, disenchanted and leaving Shanghai (bottom)

To conclude, although the Chinese Communists downplayed religion, Chinese tradition began an official restatement shortly after the disastrous attempt to destroy all vestiges of tradition during the Cultural Revolution. In a beginning effort at recovery, in 1987, China Central Television produced a 36 episode series of one of the great modern Chinese classics, The Dream of the Red Chamber/Mansion [Hong Lou Mang 紅樓夢 by Cao Xueqin and Gao E]. However, not surprisingly, Taoist and Buddhist aspects of the novel were significantly downplayed, to the point of making the adaptation rather lean, to say the least. To compare, one of the vignettes featured in The Classic for Girls, depicts one woman’s young daughter kidnapped, most likely for possible sale. This may have be a conscious effort to recreate a beginning episode in the aforementioned novel, that is, an acknowledgement and a return to tradition.

Michael Presley is currently a Southerner who briefly sojourned in China, where he lived and studied with a Taoist priestess. His own outlook is best described by English comedic stylist Vivian Stanshall’s description of the (fictional) Sir Henry of Rawlinson End: changing yet changeless as canal water, armored but not always effete, opsimath and eremite; still feudal.

Ce sont finalement, la géopolitique et l’économie qui dictent l’agenda de la politique étrangère de l’Occident (et par extension de la Turquie) en Asie centrale et en Chine. Il s’agit d’une tentative d’étouffer le développement économique, tant de la Russie que de la Chine, et d’empêcher les deux puissances de poursuivre leur double démarche de coopération et d’intégration régionale. Ainsi considérée, la Turquie devient une pièce géante instrumentalisée pour garder la Russie et la Chine séparées mais aussi garder séparées la Chine et l’Europe. Il y a beaucoup de magie derrière le rideau proverbial.

Ce sont finalement, la géopolitique et l’économie qui dictent l’agenda de la politique étrangère de l’Occident (et par extension de la Turquie) en Asie centrale et en Chine. Il s’agit d’une tentative d’étouffer le développement économique, tant de la Russie que de la Chine, et d’empêcher les deux puissances de poursuivre leur double démarche de coopération et d’intégration régionale. Ainsi considérée, la Turquie devient une pièce géante instrumentalisée pour garder la Russie et la Chine séparées mais aussi garder séparées la Chine et l’Europe. Il y a beaucoup de magie derrière le rideau proverbial.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

De Europese Unie en de NAVO worden tegenwoordig als de grootste vredesprojecten aller tijden beschouwd. Niets is meer ironisch. De Belgische staat is nog nooit in zoveel oorlogen verwikkeld geraakt als sinds haar toetreden tot de NAVO. Al haar oorlogen voor deze toetreding waren zuiver defensief, terwijl België inmiddels een ware agressor is geworden. Enkel al de laatste 20 jaren heeft België unilateraal de oorlog verklaard aan Joegoslavië, Servië, Afghanistan en Libië. Daarnaast heeft ze als NAVO-lidstaat indirect de oorlog(-en) van de VS met Irak gefaciliteerd.

De Europese Unie en de NAVO worden tegenwoordig als de grootste vredesprojecten aller tijden beschouwd. Niets is meer ironisch. De Belgische staat is nog nooit in zoveel oorlogen verwikkeld geraakt als sinds haar toetreden tot de NAVO. Al haar oorlogen voor deze toetreding waren zuiver defensief, terwijl België inmiddels een ware agressor is geworden. Enkel al de laatste 20 jaren heeft België unilateraal de oorlog verklaard aan Joegoslavië, Servië, Afghanistan en Libië. Daarnaast heeft ze als NAVO-lidstaat indirect de oorlog(-en) van de VS met Irak gefaciliteerd.

Un simple coup d'œil sur les forces en présence sur la plage de Marathon donne les Perses très largement gagnants. Comme on sait, ce fut le contraire. Mais un siècle plus tard, la Grèce, puissante et relativement démocratique sur de nombreux points, s'effondre presque dans les guerres civiles du Péloponnèse, avant d'être soumise par un petit royaume grec du Nord qui, avec Alexandre le grand à sa tête, conquerra l'immense territoire s'étendant de l'Europe à l'Inde. Personne n'aurait pu prédire que ce petit royaume deviendrait maître de la terre au point que les Juifs, des irréductibles s'il en est, traduisirent leurs textes sacrés en grec, la Septante. On mesure encore aujourd'hui toute l'ampleur de cette conquête en Égypte entre autres, où une ville s'appelle Alexandrie. Même chose en Afghanistan où la nouvelle de Rudyard Kipling, L'homme qui voulait être roi et le beau film qu'on en a tiré, évoquent Iskander, c'est-à-dire Alexandre le grand.

Un simple coup d'œil sur les forces en présence sur la plage de Marathon donne les Perses très largement gagnants. Comme on sait, ce fut le contraire. Mais un siècle plus tard, la Grèce, puissante et relativement démocratique sur de nombreux points, s'effondre presque dans les guerres civiles du Péloponnèse, avant d'être soumise par un petit royaume grec du Nord qui, avec Alexandre le grand à sa tête, conquerra l'immense territoire s'étendant de l'Europe à l'Inde. Personne n'aurait pu prédire que ce petit royaume deviendrait maître de la terre au point que les Juifs, des irréductibles s'il en est, traduisirent leurs textes sacrés en grec, la Septante. On mesure encore aujourd'hui toute l'ampleur de cette conquête en Égypte entre autres, où une ville s'appelle Alexandrie. Même chose en Afghanistan où la nouvelle de Rudyard Kipling, L'homme qui voulait être roi et le beau film qu'on en a tiré, évoquent Iskander, c'est-à-dire Alexandre le grand.

La politique avant tout, disait Maurras. Parlons plutôt, comme Baudelaire, d’antipolitisme. On sait que le poète, porté, en 1848, par un enthousiasme juvénile, avait participé physiquement aux événements révolutionnaires, appelant même, sans doute pour des raisons peu nobles, à fusiller son beau-père, le général Aupick. Cependant, face à la niaiserie des humanitaristes socialistes, à la suite de la sanglante répression, en juin, de l’insurrection ouvrière (il gardera toujours une tendresse de catholique pour le Pauvre, le Travailleur, et il fut un admirateur du poète et chansonnier populiste Pierre Dupont), et devant le cynisme bourgeois (Cavaignac, le bourreau des insurgés, fut toujours un républicain de gauche), il éprouva et manifesta un violent dégoût pour le monde politique, sa réalité, sa logique, ses mascarades, sa bêtise, qu’il identifiait, comme son contemporain Gustave Flaubert, au monde de la démocratie, du progrès, de la modernité. Ce dégoût est exprimé rudement dans ses brouillons très expressifs, aussi déroutants et puissants que les Pensées de Pascal, Mon cœur mis à nu, et les Fusées, qui appartiennent à ce genre d’écrits littéraires qui rendent presque sûrement intelligent, pour peu qu’on échappe à l’indignation bien pensante.

La politique avant tout, disait Maurras. Parlons plutôt, comme Baudelaire, d’antipolitisme. On sait que le poète, porté, en 1848, par un enthousiasme juvénile, avait participé physiquement aux événements révolutionnaires, appelant même, sans doute pour des raisons peu nobles, à fusiller son beau-père, le général Aupick. Cependant, face à la niaiserie des humanitaristes socialistes, à la suite de la sanglante répression, en juin, de l’insurrection ouvrière (il gardera toujours une tendresse de catholique pour le Pauvre, le Travailleur, et il fut un admirateur du poète et chansonnier populiste Pierre Dupont), et devant le cynisme bourgeois (Cavaignac, le bourreau des insurgés, fut toujours un républicain de gauche), il éprouva et manifesta un violent dégoût pour le monde politique, sa réalité, sa logique, ses mascarades, sa bêtise, qu’il identifiait, comme son contemporain Gustave Flaubert, au monde de la démocratie, du progrès, de la modernité. Ce dégoût est exprimé rudement dans ses brouillons très expressifs, aussi déroutants et puissants que les Pensées de Pascal, Mon cœur mis à nu, et les Fusées, qui appartiennent à ce genre d’écrits littéraires qui rendent presque sûrement intelligent, pour peu qu’on échappe à l’indignation bien pensante.

Nachdem die Zahl der Anhänger der nordischen Glaubensrichtung sich auf Island seit dem Jahr 2000 verfünffacht hat, soll in der isländischen Hauptstadt Reykjavík erstmals seit der Wikingerzeit wiedereine heidnische Kultstätte entstehen.Nach der Christianisierung Islands im Jahre 1000 durfte das Heidentum nicht mehr praktiziert werden.

Nachdem die Zahl der Anhänger der nordischen Glaubensrichtung sich auf Island seit dem Jahr 2000 verfünffacht hat, soll in der isländischen Hauptstadt Reykjavík erstmals seit der Wikingerzeit wiedereine heidnische Kultstätte entstehen.Nach der Christianisierung Islands im Jahre 1000 durfte das Heidentum nicht mehr praktiziert werden.

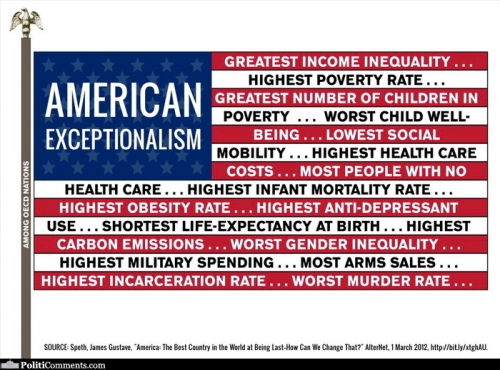

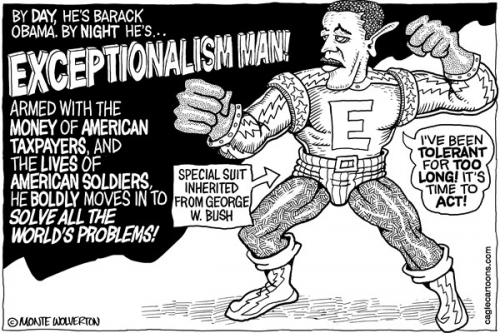

All that should be impressive enough for a discredited, long dead authoritarian thinker. But Schmitt’s dictum also became a philosophical foundation for the exercise of American global power in the quarter century that followed the end of the Cold War. Washington, more than any other power, created the modern international community of laws and treaties, yet it now reserves the right to defy those same laws with impunity. A sovereign ruler should, said Schmitt, discard laws in times of national emergency. So the United States, as the planet’s last superpower or, in Schmitt’s terms, its global sovereign, has in these years repeatedly ignored international law, following instead its own unwritten rules of the road for the exercise of world power.

All that should be impressive enough for a discredited, long dead authoritarian thinker. But Schmitt’s dictum also became a philosophical foundation for the exercise of American global power in the quarter century that followed the end of the Cold War. Washington, more than any other power, created the modern international community of laws and treaties, yet it now reserves the right to defy those same laws with impunity. A sovereign ruler should, said Schmitt, discard laws in times of national emergency. So the United States, as the planet’s last superpower or, in Schmitt’s terms, its global sovereign, has in these years repeatedly ignored international law, following instead its own unwritten rules of the road for the exercise of world power.