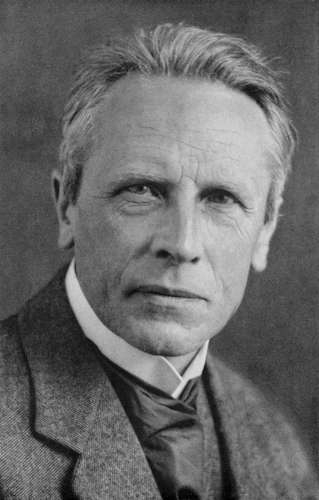

Ludwig Klages (1872–1956) was one of the most interesting thinkers of the twentieth century. He was also one of the most complex. Klages was a philosopher, a psychologist, and a leading graphologist. Together with Alfred Schuler and Karl Wolfskehl, he formed the ‘Cosmic Circle’ in Munich. The Circle consisted of the milieu around the poet Stefan George, but it did not fully adhere to George’s patriarchal worldview.

Klages was a productive and original thinker. Among other things, he was the father of the term ‘id’ which was later to be picked up by Sigmund Freud. Klages also coined the term logocentrist, which today is a term used in certain types of feminist theories. He gave his psychological school the name characterology, and wrote several classics on graphology.

Klages was a man of paradox. In his writings he was an anti-Semite, yet he spent several years editing the works of his Jewish-Hungarian colleague, the natural philosopher Melchior Palagyi, after he had passed away. Klages was not very popular in the Third Reich, but neither did he renounce his theories about Judaism even after the Second World War, either. Recently, Jürgen Habermas stated that there is much of value in Klages, given that he was such an original and interesting thinker. But his unique perspective is now largely forgotten. It is therefore of great value that Arktos Media has published two books consisting of excerpts from his writings, translated by Joseph D Pryce (Pryce has also written a valuable introduction to both collections). This present review focuses on the first of them, The Biocentric Worldview.

The Biocentric Worldview

‘Wild boar, ibex, fox, pine marten, weasel, duck and otter — all animals with which the legends dear to our memory are intimately intertwined — are shrinking in numbers, where, that is, they have not already become extinct…’

— Klages, 1913

What I appreciate the most in Klages’ thought is his so-called biocentric worldview. Klages claims that the distinction between ‘idealism’ and ‘materialism’ is rather irrelevant. In its place he describes a deeper, less well-known historical conflict. Klages puts Life in the centre, but he also identifies an anti-Life force that gradually infiltrated the world and took it over. Klages uses the German terms Seele and Geist, usually translated as Spirit and Mind. There is an intimate connection between Life and Spirit, but Mind is connected to abstractions, like ‘sin’, ‘will to power’, and similar concepts. Klages illuminates the difference:

‘Just as the philosopher of spirit considers everything that denies spirit to be a “sin”, the philosopher of life regards that which denies life to be an offense… no one speaks of a sin against a tree, but men have certainly spoken in the past — and even today many still speak — of an offense against a tree.’

Among these expressions of anti-Life he mentions moralism, Judaism, and Christianity, as well as capitalism and militarism. Nietzsche’s ‘will to power’ also risks becoming a part of the anti-Life forces and an unhealthy obsession. Klages develops a useful deep ecological perspective, related to and complementing Naess, Abbey, and Linkola. He also describes how ‘progress’ has hurt the world. In the essay ‘Man and Earth’, Klages describes how animals and plants became extinct, but also how folk cultures and authentic human emotions are pushed aside. Klages was an anti-colonialist, and discusses how both species of animals and human cultures are extinguished. In their place everything, is homogenised, and the vampire that is Geist spreads over the world. Thus Klages connects the threat against biological diversity with the threat against cultural.

‘Modern man´s conscious striving for power far surpasses that of any previous epoch… in the service of human needs, the ever-increasing mechanization has brought about the desecration of the natural world.’

— Klages

These essays are also interesting from the perspective of the history and philosophy of science. Klages analyses both psychoanalysis and Socrates, among many other things. He criticises concepts like ‘progress’ and utopianism as being hostile to Life. His perspective places primary value on Spirit and Life, and on the non-conscious and the qualitative. One does well to compare Klages with Guénon’s The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times, along with Heidegger and Alexander Jacob’s De Naturae Natura.

Klages and Romanticism

Klages and Romanticism

‘Man should look upon the harvested fruits of the unconscious as an unexpected windfall bestowed by Heaven above.’

— Goethe

Among Klages’ own sources we find Nietzsche and the pre-Socratic philosophers. We also find the German Romantics and Goethe. Among the Romantics, Klages focuses on the now largely forgotten Carl Gustav Carus. He demonstrates that German Romanticism has permanent value.

In one’s own life, Klages is of value in showing that too much Geist leads to a worse and less authentic life. When the process has gone too far, one loses the ability to perceive the beauty of a forest, and instead only sees it as something merely quantifiable: as a bunch of timber. Likewise, the Romantics and Klages are also of use in politics. They show that the tendency towards hyper-politicisation and ideological thinking are among the enemies of Life. Family, nature, emotions, beauty, folk culture — they are all threatened by too much Geist. When Karlheinz Weissmann identifies the living as the leitmotiv of conservatism, or when Heinrich von Leo described his mission as protecting the ‘God-given, real life, in its development following its inner forces’, they are clearly related to Klages. Conservatism, defined as taking care of the living, not only animals and plants but also such ‘organisms’ as cultures, can also be biocentric.

When it comes to the philosophy of science, Carus, Goethe, and Klages are also of great use, given their focus on the whole rather than on the parts of things, on the sub- or non-conscious, and on reality and life above the prevailing focus on the mechanical and quantifiable. Klages quotes Carus:

‘…the key to an understanding of conscious thought resides in the realm of the unconscious.’

The Biocentric Worldview is thus of great value due to its deep ecological qualities as well as Klages’ original conception of history. Klages’ description of the rise and vampire-like spread of Geist has much in common with Nietzsche’s description of how ressentiment and slave morality takes over the world. (However, some aspects of Nietzsche are also dangerously close to the vampire.)

Klages is not a determinist. He does not rule out that Spirit and Life may be defended against Mind. He also reminds us that the goal of a Spirit-oriented science is to understand, rather than to reduce and manipulate. His role models are thus heroes, poets, and gods. The anthology is highly recommended.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

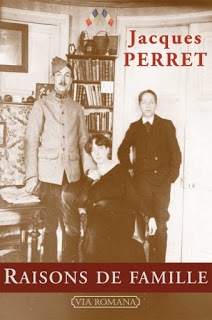

Les Editions Via Romana viennent de publier

Les Editions Via Romana viennent de publier  L'intérêt du livre de Jacques Perret est là, nous narrer l'avant-guerre, « la paix des familles, l'état d'innocence, l'harmonie universelle » ou « la cueillette des prunes », les devoirs de classe, les jeux en plein air, au Jardin du Luxembourg des distractions enfantines, les cabanes et les courses à vélo, agrémentées de pénibles leçons de piano. Dès lors, en lisant le livre, on ne peut pas commémorer la grande guerre sans faire des parallèles avec le repli familial des années 90 qui anticipe ce que sera le choc historique des années 2015-2025. Certes en 1912 pas de grand remplacement ni de théorie du genre obligatoire, de totalitarisme de l'édredon, rien de tout cela dans le portrait d'une famille plutôt traditionnelle d'avant-guerre avec le camembert et le pinard à la sortie de la Messe, ou les enfants montés de force à l'étage quand les grands finissaient d'arroser la soirée au calvados dans le salon : « De fumants éclats montaient jusqu'aux chambres des enfants et nous comprenions alors vaguement dans le demi-sommeil, quelle institution difficile et miraculeuse était la famille où sans être d'accord sur tout on peut s'embrasser à propos de rien ». En réalité, aujourd'hui, les enfants ne dorment plus très tôt, ne montent dans leurs chambres que pour les jeux vidéos tandis que leurs parents pianotent sur leurs portables sans même se parler ou se poser des questions. Mais n'est-ce pas aussi un climat d'avant-guerre, le climat insouciant d'une guerre mondiale qui sera hybride et civile mais dont on veut dénie la probable réalité barbaresque ou nucléaire ? En fait, ce paradis familial que narre Jacques Perret avant la grande catastrophe de 14 existe encore même s'il n'y a plus d'éden républicain capable de fomenter la fierté grandiloquente de l'humble devoir patriotique. Il n'y a plus de nation mais des rapatriements d'exilés ou d'immigrés dans des drapeaux brûlés, déchirés ou remplacés sur les places publiques par les bannières ennemies de républiques islamiques.

L'intérêt du livre de Jacques Perret est là, nous narrer l'avant-guerre, « la paix des familles, l'état d'innocence, l'harmonie universelle » ou « la cueillette des prunes », les devoirs de classe, les jeux en plein air, au Jardin du Luxembourg des distractions enfantines, les cabanes et les courses à vélo, agrémentées de pénibles leçons de piano. Dès lors, en lisant le livre, on ne peut pas commémorer la grande guerre sans faire des parallèles avec le repli familial des années 90 qui anticipe ce que sera le choc historique des années 2015-2025. Certes en 1912 pas de grand remplacement ni de théorie du genre obligatoire, de totalitarisme de l'édredon, rien de tout cela dans le portrait d'une famille plutôt traditionnelle d'avant-guerre avec le camembert et le pinard à la sortie de la Messe, ou les enfants montés de force à l'étage quand les grands finissaient d'arroser la soirée au calvados dans le salon : « De fumants éclats montaient jusqu'aux chambres des enfants et nous comprenions alors vaguement dans le demi-sommeil, quelle institution difficile et miraculeuse était la famille où sans être d'accord sur tout on peut s'embrasser à propos de rien ». En réalité, aujourd'hui, les enfants ne dorment plus très tôt, ne montent dans leurs chambres que pour les jeux vidéos tandis que leurs parents pianotent sur leurs portables sans même se parler ou se poser des questions. Mais n'est-ce pas aussi un climat d'avant-guerre, le climat insouciant d'une guerre mondiale qui sera hybride et civile mais dont on veut dénie la probable réalité barbaresque ou nucléaire ? En fait, ce paradis familial que narre Jacques Perret avant la grande catastrophe de 14 existe encore même s'il n'y a plus d'éden républicain capable de fomenter la fierté grandiloquente de l'humble devoir patriotique. Il n'y a plus de nation mais des rapatriements d'exilés ou d'immigrés dans des drapeaux brûlés, déchirés ou remplacés sur les places publiques par les bannières ennemies de républiques islamiques.

Klages puts Life in the centre, but he also identifies an anti-Life force that gradually infiltrated the world and took it over.

Klages puts Life in the centre, but he also identifies an anti-Life force that gradually infiltrated the world and took it over.

Dumont, nato a Salonicco nel 1911, si trasfersce successivamente in Francia, dove negli anni giovanili militerà nel Partito Comunista Francese, occupandosi delle varie sollecitazioni innovatrici della vivace realtà politica parigina. Presto si interessa di etnologia al punto di frequentare i corsi di Marcel Mauss al College de France, contro la volontà dei suoi genitori che lo avrebbero voluto ingegnere. Arruolato nell’esercito francese durante il secondo conflitto mondiale e finito prigioniero in un campo di detenzione tedesco, Dumont nel dopoguerra continua ad approfondire i suoi studi. Nel 1949 fa il suo primo viaggio in India, dove tornerà periodicamente per tutto il corso della sua vita. A partire dal confronto con l’India, comincia a sviluppare la dicotomia fondamentale tra l’Homo Aequalis, tipico dell’Occidente moderno, e l’Homo Hierarchicus. Proprio attorno a questa tematica, Dumont struttura alcuni dei suoi saggi più importanti e riconosciuti (si segnalano in particolare “La civiltà indiana e noi” del 1964 e “Homo Hierarchicus, saggio sul sistema delle caste” del 1966). Svincolando la sua analisi dal pregiudizio secondo il quale la società individualistica rappresenterebbe l’apice di un progresso (da leggere in contrapposizione alla barbarie di un sistema arcaico come quello delle caste), Dumont concentra la sua attenzione su uno dei testi più importanti della tradizione induista: il Sanathana Dharma.

Dumont, nato a Salonicco nel 1911, si trasfersce successivamente in Francia, dove negli anni giovanili militerà nel Partito Comunista Francese, occupandosi delle varie sollecitazioni innovatrici della vivace realtà politica parigina. Presto si interessa di etnologia al punto di frequentare i corsi di Marcel Mauss al College de France, contro la volontà dei suoi genitori che lo avrebbero voluto ingegnere. Arruolato nell’esercito francese durante il secondo conflitto mondiale e finito prigioniero in un campo di detenzione tedesco, Dumont nel dopoguerra continua ad approfondire i suoi studi. Nel 1949 fa il suo primo viaggio in India, dove tornerà periodicamente per tutto il corso della sua vita. A partire dal confronto con l’India, comincia a sviluppare la dicotomia fondamentale tra l’Homo Aequalis, tipico dell’Occidente moderno, e l’Homo Hierarchicus. Proprio attorno a questa tematica, Dumont struttura alcuni dei suoi saggi più importanti e riconosciuti (si segnalano in particolare “La civiltà indiana e noi” del 1964 e “Homo Hierarchicus, saggio sul sistema delle caste” del 1966). Svincolando la sua analisi dal pregiudizio secondo il quale la società individualistica rappresenterebbe l’apice di un progresso (da leggere in contrapposizione alla barbarie di un sistema arcaico come quello delle caste), Dumont concentra la sua attenzione su uno dei testi più importanti della tradizione induista: il Sanathana Dharma. Si comprende bene come un tale individualismo si ponga agli antipodi con la concezione olistica/tradizionale: questo non vuol banalmente significare che in passato la totalità delle persone fosse altruista, ma che la comunità viveva coesa attorno a dei valori universalmente riconosciuti. Nell’induismo, per esempio, non esiste l’idea che per essere felici bisogna gratificare il proprio ego, ma vige, piuttosto, il pensiero per cui ognuno debba scoprire il ruolo assegnatogli dal destino e vivere in armonia con esso e ciò che si ha intorno: ciò che gratifica veramente l’esistenza della persona è insomma trovare il proprio posto all’interno della comunità, non emanciparsi da essa. L’individuo induista si concepisce infatti come parte del cosmo e non come un atomo portatore di valori naturali, privo di interdipendenza. Lo stesso asceta che si allontana dalla società non lo fa in nome di un ripiegamento individualista: si tratta piuttosto dell’aspirazione ad una realizzazione metafisico-cosmica superiore a quella basata su una vita comunitaria, ma in cui trionfa sempre lo stesso spirito olistico (non si mette in discussione il valore della comunità in quanto tale), distinto sia dall’individualismo extramondano sia da quello mondano.

Si comprende bene come un tale individualismo si ponga agli antipodi con la concezione olistica/tradizionale: questo non vuol banalmente significare che in passato la totalità delle persone fosse altruista, ma che la comunità viveva coesa attorno a dei valori universalmente riconosciuti. Nell’induismo, per esempio, non esiste l’idea che per essere felici bisogna gratificare il proprio ego, ma vige, piuttosto, il pensiero per cui ognuno debba scoprire il ruolo assegnatogli dal destino e vivere in armonia con esso e ciò che si ha intorno: ciò che gratifica veramente l’esistenza della persona è insomma trovare il proprio posto all’interno della comunità, non emanciparsi da essa. L’individuo induista si concepisce infatti come parte del cosmo e non come un atomo portatore di valori naturali, privo di interdipendenza. Lo stesso asceta che si allontana dalla società non lo fa in nome di un ripiegamento individualista: si tratta piuttosto dell’aspirazione ad una realizzazione metafisico-cosmica superiore a quella basata su una vita comunitaria, ma in cui trionfa sempre lo stesso spirito olistico (non si mette in discussione il valore della comunità in quanto tale), distinto sia dall’individualismo extramondano sia da quello mondano.