The following is the text of a talk given in London on May 27, 2018 at The Poet at War, an event convened by Vortex Londinium.

“We want an European religion. Christianity is verminous with semitic infections. What we really believe is the pre-Christian element which Christianity has not stamped out . . .”[1] [2]

“If a race NEGLECTS to create its own gods, it gets the bump.”[2] [3]

“The glory of the polytheistic anschauung is that it never asserted a single and obligatory path for everyone. It never caused the assertion that everyone was fit for initiation and it never caused an attempt to force people into a path alien to their sensibilities.

Paganism never feared knowledge. It feared ignorance, and under a flood of ignorance it was driven out of its temples.”[3] [4]

Pound is a forest and one is in need of principles by which to navigate him, otherwise one is apt to lose sight of the wood for the trees, as we say in English. What I shall call Pound’s paganism can, I submit, offer one of the more direct routes into the man and his work, and in particular, into the heart of his most difficult: The Cantos.

At the same time, in the opposite direction, his poetry and prose can bring one to a better understanding of this part of our heritage and its potentialities, and here I intend no narrowly partisan point. By paganism I mean a central stream in European civilization, something that has participated in the formation of Christianity just as much as offering alternative visions of life. To give one example, the theologically fundamental doctrine of the Trinity is arguably a modified form of the Neo-Platonic triad of the One, Intellect, and Soul, in which the latter two emanate from the One and yet both are equivalent to it and yet not equivalent to it. St. Augustine in his Confessions confirms [5] that he and other Christian intellectuals believed thus that the Neo-Platonists had already had an awareness of the persons of the Trinity.

Pound was pagan in three respects. First, he accepted as true ideas from the pre- and non-Christian philosophers. One finds a Neo-Platonic orientation of mind, in the foreground or background, from the very first poem in his first published anthology, “Grace Before Song,” to the very last words of the final Canto, “Canto CXVI”:

To confess wrong without losing rightness:

Charity I have had sometimes,

I cannot make it flow thru.

A little light, like a rushlight

to lead back to splendour.[4] [6]

It is the idea of light as the symbol for a higher form of reality, of a more real reality, which all things may draw closer towards and so perfect themselves – it is this idea that unites how he speaks of the ethical precepts of Confucius, the financial theories of Major Douglas, the politics of John Adams, and the poetry of Cavalcanti, all aids towards the perfected man and the perfected society.

This is that first poem, from A Lume Spento, in 1908:

Lord God of heaven that with mercy dight

Th’alternate prayer wheel of the night and light

Eternal hath to thee, and in whose sight

Our days as rain drops in the sea surge fall,

As bright white drops upon a leaden sea

Grant so my songs to this grey folk may be:

As drops that dream and gleam and falling catch the sun

Evan’scent mirrors every opal one

Of such his splendor as their compass is,

So, bold My Songs, seek ye such death as this.[5] [7]

The second and obvious respect in which Pound was pagan was that he accepted as valid indigenous images, names, and myths, by which Deity has revealed Itself to the Europeans. He claimed that the only safe guides in religion were Ovid’s Metamorphoses and the writings of Confucius.[6] [8]

The second and obvious respect in which Pound was pagan was that he accepted as valid indigenous images, names, and myths, by which Deity has revealed Itself to the Europeans. He claimed that the only safe guides in religion were Ovid’s Metamorphoses and the writings of Confucius.[6] [8]

Which brings one to the third respect. He was pagan in his ethics, in the sense that he sought precepts that had arisen through tradition, were enshrined in custom, and were implicit in the natural order and man’s place within it. When he was captured by the partisans after the war and assumed he was about to face execution, it was the Analects of Confucius that he took with him, which he considered a better guide to moral behavior than the Bible: “The unshakable wisdom of Confucius . . . in comparison with which Christianity is a fad.”[7] [9]

In Pagan Ethics: Paganism as a World Religion,[8] [10] Professor Michael York unambiguously speaks of Confucianism as a religion, with its principles of solicitous care, decency, and benevolence, and the obverse of the Golden Rule: Do not do to others as you would not have done to yourself. Another example: Act in such a way that your descendants will be glad. In its emphasis on correct relationships between oneself and one’s family, between oneself and those above one and below one in society, between oneself and those who came before one in time, and between oneself and those who will come after one, Pound perceived the same multi-directional communitarian values that he found in Fascism.

Cut to London in the years following 1908, when Pound settled here. With the rise of science and biblical scholarship precipitating a crisis of faith in the mid-nineteenth century, some of the space hitherto occupied by the established denominations began to be filled by mysticism, occultism, and philosophies drawn from earlier times or from other parts of the world; and this was nowhere more evident than within the artistic circles in which Pound would move. The Theosophical Society was founded by Madame Blavatsky in 1875, and one of the emblematic texts of the aesthetic movement, Walter Pater’s work of fiction, Marius the Epicurean, appeared ten years later, providing a fully fleshed-out account of how non-Christian, Classical concepts of spirituality and the Good might be just as valid a way to live well as the prevailing religious norms.

The major source which fed Pound’s development as a religious thinker was, as has been indicated, Neo-Platonism, which is simply the continuation of Plato’s ideas, namely their elaboration and exegesis, principally through Plotinus but also through a host of others, including Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola in Italy, and later through the translations of the eighteenth-century English Neo-Platonist Thomas Taylor, whose books were read by and influenced poets such as Blake, Shelley, and Yeats.

What Pound found within Neo-Platonism was:

- The idea of henosis, that is to say union or reunion with the absolute One, which could manifest as a mystical experience. On his deathbed, Plotinus is reported to have summarized his teaching thus: “Try to bring back the god in oneself to the divine in the All.”[9] [11]

- The idea that an individual soul has a better, higher, and true self, and that this superior self seeks its return to the One that gave birth to all creation.

- The idea that experience results from the tension between the poles of the temporal and the eternal.

- The idea that the beauty of the absolute One descends into the beauty of the Platonic world of forms, and is then instantiated in the material world.

It seems Pound was congenitally disposed to such ideas. When interviewed during his stay in St. Elizabeth’s Hospital after his return to America in 1946, he said he had been under the influence of mysticism between the ages of 16 to 24.[10] [12] Later in his life, he wrote two refreshingly precise and disciplined statements of his own philosophy: “Religio, or the Child’s Guide to Knowledge (1918) and “Axiomata” (1923). The first is a catechism, a series of simple questions and answers which enunciates a pagan theology as well as any other text of such brevity of which I am aware.

He was drawn to Plotinus because Plotinus defended the value of worldly sensations and attacked their rejection by the Gnostics, who thought physicality evil in some sense. He was drawn to the idea in Plotinus that the beauty of this world is the manifestation of a celestial beauty, which we may not be able to grasp but which is yet a glimpse of a paradise that imparts to us, within a limited time, an unlimited joy.

But unlike Plotinus, who thought that this glimpse into the world of ideal forms was but the penultimate stage in the union with the One, a union with the absolute, an entity without parts or qualities, Pound seemed to believe that this was an unwarranted assumption, which one’s highest experiences neither legitimated nor needed. His type of paganism was without dogmatism or unnecessary abstraction: “To replace the marble Goddess on Her pedestal at Terracina is worth more than any metaphysical argument.”[11] [13]

The vast, sprawling, expansive sequence of poems called The Cantos is Pound’s attempt to fashion a work that embraced all things that seemed relevant, all things that needed to be said. It makes use of twenty-five languages – twenty-six if one includes musical notation. It draws on Dante’s Divine Comedy in the progression from the dark depths to the upper regions; Ovid’s Metamorphoses in the treatment of impermanence and change, and of the human and the mythic; and Homer’s Odyssey, in the hero’s endeavor to succeed over obstacles and achieve victory, and victory not merely in worldly terms.

Plotinus regarded Homer’s Odyssey as a metaphor for the journey of the individual soul to return home into the Great Soul of the absolute, and this became for Pound almost a foundational myth for civilization. The Cantos begins therefore with an account of Odysseus making landfall and offering sacrifice to the gods. Paganism, in its Hellenic manifestation, he saw as the golden thread that ran overtly through the Classical era, covertly through the Middle Ages, and surfaced again in the Renaissance, indeed being implicit alongside the explicit Christianity of his favorite author, Dante Alighieri.

In the essay “Psychology and Troubadours” (1912), he posited a continuity of Classical paganism in the south of France:

Provence was less disturbed than the rest of Europe by invasion . . . if paganism survived anywhere, it would have been, unofficially, in the Langue d’Oc. That the spirit was, in Provence, Hellenic, is seen readily enough by anyone who will compare the Greek Anthology with the work of the Troubadours. They have, in some way, lost the names of the Gods, and remembered the names of lovers.[12] [14]

One recognizes a person that one actually knows by sight, by who the person is, not because of the name. A person may be called by different names yet be the same person still. “Tradition inheres in the images of the Gods, and gets lost in dogmatic definitions . . . But the images of the Gods . . . move the soul to contemplation and preserve the tradition of the undivided light.”[13] [15]

One recognizes a person that one actually knows by sight, by who the person is, not because of the name. A person may be called by different names yet be the same person still. “Tradition inheres in the images of the Gods, and gets lost in dogmatic definitions . . . But the images of the Gods . . . move the soul to contemplation and preserve the tradition of the undivided light.”[13] [15]

Before I close with a poem, I should like to put forward two conclusions.

First, with the insights into the Cantos offered by Neoplatonic paganism, one can put to one side some of the less inspiring critical readings – that it is a record of a lifetime’s reading, or an old man’s descent into confusion – and it becomes again the epic he intended it to be, the struggle of light against darkness, of heroes with themselves and with the world to reach a blessed place.

And second, with Pound’s veneration for the past and his appetite for the future, for making it new, as he put it, with his courage and capacity for friendship, with the range of his enthusiasms, and the range of what he was not satisfied with, he is an ideal figure to head any movement of European rebirth. And this poem, “Surgit Fama”[14] [16] (“it rises to fame”), seems to be about that more than anything else. The first stanza depicts a stirring in the world, the coming of Korè who is Persephone, the returning and reborn Spring; in consort with Leuconoë, the girl to whom Horace addresses the famous injunction to seize the day, carpe diem.[15] [17] In the second stanza, when the poet tries to render this into verse, he has to resist any superfluity, any unnecessary words that may be circulated as rumor or bent in their meaning, which he feels Hermes may tempt him to, and he addresses himself, exhorting himself to speak true. And in the final stanza that is what he does, when he says how in Delos, the island where it was said Apollo and Artemis were born, once again shall rites be enacted and the story continued.

There is a truce among the Gods,

Korè is seen in the North

Skirting the blue-gray sea

In gilded and russet mantle.

The corn has again its mother and she, Leuconoë,

That failed never women,

Fails not the earth now.

The tricksome Hermes is here;

He moves behind me

Eager to catch my words,

Eager to spread them with rumour;

To set upon them his change

Crafty and subtle;

To alter them to his purpose;

But do thou speak true, even to the letter:

“Once more in Delos, once more is the altar a quiver.

Once more is the chant heard.

Once more are the never abandoned gardens

Full of gossip and old tales.”

Notes

[1] [18] Ezra Pound, “Statues of Gods,” The Townsman, August 1939; in William Cookson (ed.), Ezra Pound, Selected Prose 1909-1965 (London: Faber and Faber, 1973), p. 71.

[2] [19] Ezra Pound, “Deus et Amor,” The Townsman, June 1940; Selected Prose, p. 72.

[3] [20] Ezra Pound, “Terra Italica,” The New Review, Winter, 1931-2; Selected Prose, p. 56.

[4] [21] Ezra Pound, The Cantos (London: Faber and Faber, 1975), p. 743.

[5] [22] Michael John King (ed.), The Collected Early Poems of Ezra Pound, ed. Michael John King (London: Faber and Faber, 1977), p. 7.

[6] [23] In a letter from 1922 to Dr. Felix E. Schelling, in D. D. Paige (ed.), The Selected Letters of Ezra Pound, 1907-1941 (London: Faber and Faber, 1950), p. 182.

[7] [24] “Statues of Gods,” Selected Prose, p. 71.

[8] [25] Michael York, Pagan Ethics: Paganism as a World Religion (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2016), p. 356.

[9] [26] Porphyry, The Life of Plotinus, in Plotinus, vol. I, trans. Arthur Hilary Armstrong (Cambridge, Mass.: Loeb Classics, Harvard University Press, 1995), p. 7.

[10] [27] Peter Liebregts, Ezra Pound and Neoplatonism (Madison: Rosemont Publishing, 2004), p. 34.

[11] [28] Ezra Pound, “A Visiting Card,” written in Italian and first published in Rome in 1942; the translation by John Drummond was first published by Peter Russell in 1952; Selected Prose, p. 290.

[12] [29] Ezra Pound, The Spirit of Romance (London: Peter Owen, 1952), p. 90.

[13] [30] “A Visiting Card”; Selected Prose, p. 277.

[14] [31] Ezra Pound, Collected Shorter Poems (London: Faber and Faber, 1952), p. 99.

[15] [32] Horace, Odes, I, XI.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

« On était exempt de ces fléaux quand on ne s’était pas encore laissé fondre aux délices, quand on n’avait de maître et de serviteur que soi. On s’endurcissait le corps à la peine et au vrai travail ; on le fatiguait à la course, à la chasse, aux exercices du labour. On trouvait au retour une nourriture que la faim toute seule savait rendre agréable. Aussi n’était-il pas besoin d’un si grand attirail de médecins, de fers, de boîtes à remèdes. Toute indisposition était simple comme sa cause : la multiplicité des mets a multiplié les maladies. Pour passer par un seul gosier, vois que de substances combinées par le luxe, dévastateur de la terre et de l’onde ! »

« On était exempt de ces fléaux quand on ne s’était pas encore laissé fondre aux délices, quand on n’avait de maître et de serviteur que soi. On s’endurcissait le corps à la peine et au vrai travail ; on le fatiguait à la course, à la chasse, aux exercices du labour. On trouvait au retour une nourriture que la faim toute seule savait rendre agréable. Aussi n’était-il pas besoin d’un si grand attirail de médecins, de fers, de boîtes à remèdes. Toute indisposition était simple comme sa cause : la multiplicité des mets a multiplié les maladies. Pour passer par un seul gosier, vois que de substances combinées par le luxe, dévastateur de la terre et de l’onde ! » Et d’évoquer la pédophilie festive de nos romains diners :

Et d’évoquer la pédophilie festive de nos romains diners :

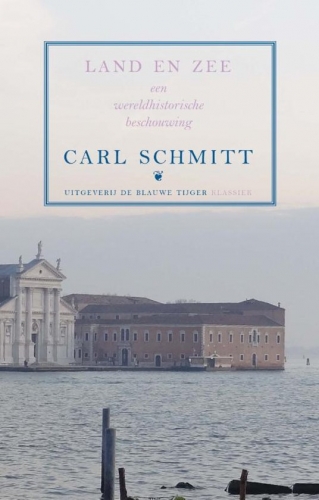

De eersten die de omslag maken zijn de oude Grieken in de klassieke Oudheid. Griekenland bestaat uit vele stadstaten, maar de zeemacht Athene en de landmacht Sparta steken in deze Griekse wereld boven allen uit. Het denken van de Grieken veranderde van een volk dat zich enkel met landbouw bezighield naar een zeemacht, omdat het op een gegeven moment het gehele oostelijke deel van de Middellandse zee ging beheersen. De Grieken waren opgesloten in deze context en ze misten de mankracht om hieruit te breken.

De eersten die de omslag maken zijn de oude Grieken in de klassieke Oudheid. Griekenland bestaat uit vele stadstaten, maar de zeemacht Athene en de landmacht Sparta steken in deze Griekse wereld boven allen uit. Het denken van de Grieken veranderde van een volk dat zich enkel met landbouw bezighield naar een zeemacht, omdat het op een gegeven moment het gehele oostelijke deel van de Middellandse zee ging beheersen. De Grieken waren opgesloten in deze context en ze misten de mankracht om hieruit te breken.

Quelle est votre définition du « cosmopolitisme », un mot qui, au XVIIIe siècle, à l’époque des Lumières, représentait le nec plus ultra : cela revenait alors, pour l’élite, à s’informer des autres cultures que celle de son pays d’origine ?

Quelle est votre définition du « cosmopolitisme », un mot qui, au XVIIIe siècle, à l’époque des Lumières, représentait le nec plus ultra : cela revenait alors, pour l’élite, à s’informer des autres cultures que celle de son pays d’origine ?

Los van het feit dat de “dreiging” om asiel aan te vragen in het buitenland als bepaalde mensen verkozen worden of als een land onafhankelijk wordt (een fenomeen dat zich sinds 1900 toch al zo’n 200 keer heeft voorgedaan in de wereld) tot de meest ridicule en zo goed als nooit uitgevoerde beloftes behoort, slaat de hele uitleg van Aerts nergens op. Voor zover ik weet behoren al die “kikkers” in Vlaanderen namelijk, net zoals Aerts zelf, tot dat belgië dat zich zo “bewust (...) [is] van die beperktheid”, zo “bereid” ook “intern en buiten de landsgrenzen iets op te steken”. Tenzij Aerts het bij zijn uitspraken over belgië alleen maar zou hebben over die onderdelen daarvan die niet Vlaams zijn, natuurlijk. Dat zou, gezien het feit dat de man nogal sterk op Frankrijk gericht is, niet eigenaardig zijn, maar als je met zo’n dédain over een bepaald onderdeel van je geliefde land spreekt, moet je ook niet raar opkijken dat dat onderdeel er vroeg of laat vandoor wil.

Los van het feit dat de “dreiging” om asiel aan te vragen in het buitenland als bepaalde mensen verkozen worden of als een land onafhankelijk wordt (een fenomeen dat zich sinds 1900 toch al zo’n 200 keer heeft voorgedaan in de wereld) tot de meest ridicule en zo goed als nooit uitgevoerde beloftes behoort, slaat de hele uitleg van Aerts nergens op. Voor zover ik weet behoren al die “kikkers” in Vlaanderen namelijk, net zoals Aerts zelf, tot dat belgië dat zich zo “bewust (...) [is] van die beperktheid”, zo “bereid” ook “intern en buiten de landsgrenzen iets op te steken”. Tenzij Aerts het bij zijn uitspraken over belgië alleen maar zou hebben over die onderdelen daarvan die niet Vlaams zijn, natuurlijk. Dat zou, gezien het feit dat de man nogal sterk op Frankrijk gericht is, niet eigenaardig zijn, maar als je met zo’n dédain over een bepaald onderdeel van je geliefde land spreekt, moet je ook niet raar opkijken dat dat onderdeel er vroeg of laat vandoor wil.

It was most likely in the context of this scientific tradition and its enemies that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, generally recognized as Germany’s greatest poet (or one of them, at any rate), later authored attacks on Newton’s ideas, such as Theory of Colors. Goethe, an early pioneer in biology and the life sciences, loathed the notion that there is anything universally axiomatic about the mathematical sciences. Goethe had one major predecessor in this, the Anglo-Irish philosopher and Anglican bishop George Berkeley. Like Berkeley, Goethe argued that Newtonian abstractions contradict empirical understandings. Both Berkeley and Goethe, though for different reasons, took issue with the common (or at least, commonly Anglo-Saxon) wisdom that “mathematics is a universal language.”

It was most likely in the context of this scientific tradition and its enemies that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, generally recognized as Germany’s greatest poet (or one of them, at any rate), later authored attacks on Newton’s ideas, such as Theory of Colors. Goethe, an early pioneer in biology and the life sciences, loathed the notion that there is anything universally axiomatic about the mathematical sciences. Goethe had one major predecessor in this, the Anglo-Irish philosopher and Anglican bishop George Berkeley. Like Berkeley, Goethe argued that Newtonian abstractions contradict empirical understandings. Both Berkeley and Goethe, though for different reasons, took issue with the common (or at least, commonly Anglo-Saxon) wisdom that “mathematics is a universal language.”

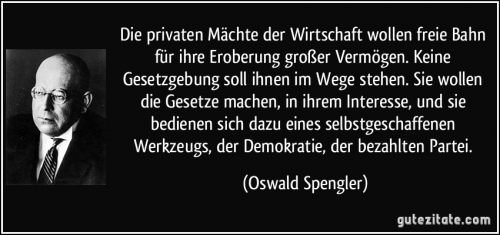

Cuvier, however, does not belong to the German transcendentalist tradition, so Spengler mentions him only peripherally. On the other hand, in the third chapter of the second volume of The Decline of the West, Spengler uses a word that Charles Francis Atkinson translates as “admitted” to describe how Cuvier propounded the theory of catastrophism. Clearly, Spengler shows himself to be more sympathetic to Cuvier than to what he calls the “English thought” of Darwin.

Cuvier, however, does not belong to the German transcendentalist tradition, so Spengler mentions him only peripherally. On the other hand, in the third chapter of the second volume of The Decline of the West, Spengler uses a word that Charles Francis Atkinson translates as “admitted” to describe how Cuvier propounded the theory of catastrophism. Clearly, Spengler shows himself to be more sympathetic to Cuvier than to what he calls the “English thought” of Darwin.