Les Indo-Européens et la domestication du cheval

par Wilfried Peter A. FISCHER

Ex: http://vouloir.hautetfort.com/

L'article qui suit est extrait d'un ouvrage que nous avions reçu en service de presse depuis longtemps déjà. Cet ouvrage est si riche en informations sur le plus lointain passé de l'Europe que nous avions eu du mal à en faire la recension. Il nous est paru plus sage d'en publier une infime partie, afin de donner au lecteur l'envie de le lire en entier. La domestication du cheval est sans doute l'une des prestations les plus spectaculaires de l'humanité indo-européenne au cours de cette période charnière entre la préhistoire et l'histoire. Les recherches de Wilfried Fischer permettent, par leur option interdisciplinaire, d'établir une nouvelle chronologie et de dégager des faits qui bouleversent la vision étriquée de la préhistoire que nous véhiculons toujours.

Notre thématique est très complexe : elle s'étend des domaines biologiques et archéologiques aux disciplines linguistiques, historiques et philosophiques. C'est pourquoi il m'apparaît opportun de partir des faits naturels. La famille des équidés était répandue dans l'ancien et le nouveau monde, même sous sa forme finale monodactyle. Peu avant la période de domestication attestée, toutes les formes américaines avaient disparu. Les mustangs, considérés erronément comme une variante du cheval sauvage, n'étaient en fait que des chevaux domestiques d'origine européenne retournés à l'état sauvage. En Eurasie et en Afrique, un seul genre (genus) a survécu : le genre equus, dans une diversité d'espèces que certains spécialistes ont classées dans diverses sous-espèces. La seule unité de base taxonomique réellement naturelle est l'espèce (species), laquelle, en règle générale, se subdivise en diverses sous-espèces, en vertu de critères géographiques dans la plupart des cas. Quant au concept de «race», il devrait être réservé aux hominidés actuels et aux espèces domestiques. Tous les représentants d'une espèce (quelle que soit leur sous-espèce) sont fertiles entre eux. Les bâtards entre les espèces d'un même genre (p. ex. les mules, les zébroïdes, etc.) sont stériles. Chaque forme d'animal domestique descend d'une espèce jadis sauvage. Depuis C. v. Linné, chaque espèce porte un nom double (p. ex. : equus africanus = âne sauvage), où le premier terme désigne le nom du genre. Les sous-espèces reçoivent un troisième terme (p. ex. equus africanus atlanticus = âne sauvage de l'Atlas). Toutes les races d'animaux domestiques reçoivent également un troisième terme, que l'on fait toutefois précéder d'un f. (pour forma = forme domestique). Ainsi : equus africanus f. asinus = âne domestique. Toutes les races de la forme domestique d'une espèce sauvage sont bien sûr non seulement fertiles entre elles mais aussi fertiles avec toutes les sous-espèces de l'espèce de base en question. Il convient de tenir compte de ce fait, lorsque l'on recense les caractéristiques spéciales des sous-espèces domestiques afin de rechercher des preuves quant à l'origine de leur domestication. Un flux de gènes de cette nature peut s'être produit à n'importe quelle période ultérieure. Un bon exemple est celui des chats domestiques, qui combinent des caractéristiques de deux sous-espèces : le chat fauve de Libye et le chat des forêts d'Europe. Sans attestation historique, le moment où ces caractéristiques se sont combinées ne peut être reconstitué.

La domestication de l'onagre

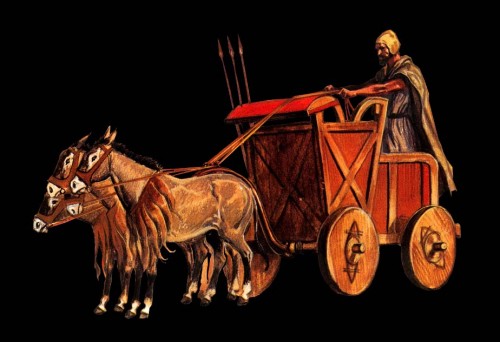

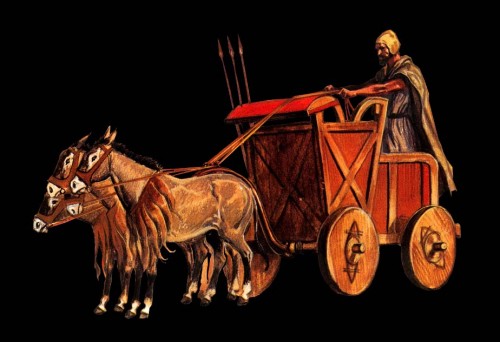

Au départ de ces données de base, retournons au cheval. À côté de l'espèce «âne sauvage», il existe en Afrique plusieurs espèces zébrines à robe tigrée qui n'ont jamais été domestiquées. Au Proche-Orient, vit l'espèce «onagre» (equus hemionus). Les hommes n'ont pas seulement chassé l'onagre mais l'on maintenu en captivité à Çatal Hüyük vers -6000. À partir de -3200, l'onagre est utilisé comme bête de somme, avec anneau nasal, à Sumer. Les zoologues nient la domestication parce qu'on n'a pas découvert d'ossements mais les historiens l'affirment parce qu'il existe des représentations imagées. L'exemple des onagres est intéressant lorsque l'on aborde les problèmes analogues dans la domestication du cheval.

La désignation de l'espèce de base «cheval sauvage» a été contestée pendant longtemps à cause de tendances inflationnaires. Ce n'est qu'en 1970 que Nobis a pu imposer le nom d'espèce : equus ferus, laquelle comprend toutes les sous-espèces fossiles de l'âge glaciaire. La systèmatique zoologique des formes récentes préfère encore et toujours le nom d'equus przewalskii.

En pratique toutefois, on utilise les désignations ferus et przewalskii comme synonymes. À l'époque historique, il n'y avait que trois sous-espèces de cheval sauvage en Eurasie septentrionale, chacune ayant été considérée comme une espèce à part entière. Comme elles ont toutes disparue, du moins à l'état sauvage, plus aucun examen empirique n'est encore possible. Il s'agit des sous-espèces suivantes :

1) E.f. = p. silvaticus = le tarpan des forêts (robe éclaircie, petite taille, extinction vers 800) ;

2) E.f. = p. gmelini = le tarpan des steppes (robe gris souris, taille moyenne, extinction en 1871) ;

3) E.f. = p. przewalskii = le tarpan oriental (robe d'un jaune rougeâtre, grande taille, extinction après 1946).

Ces trois espèces ont une crinière de poitrine et des lignes transversales sur les membres antérieurs.

La domestication originelle s'est faite en Europe

Il va de soi qu'une première domestication du cheval n'a pu s'effectuer que dans la région de son expansion naturelle. L'Orient, région des premières cultures et de la plus ancienne domestication des chèvres et des moutons, ne peut être retenu comme lieu de la première domestication du cheval. Pour l'histoire des sciences, il est intéressant de rappeler que l'on a longtemps cru que l'origine du cheval domestique (equus ferus = przewalskii f. caballus) se trouvait en Mongolie. Deux causes majeures président à cette erreur, me semble-t-il. D'abord, le tarpan oriental, cheval sauvage de Mongolie, est la seule forme sauvage encore vivante qui a pu être observée scientifiquement. Ensuite, chez les Européens, il y avait encore le choc psychologique des invasions mongoles qui agissait inconsciemment. La maîtrise parfaite du cheval par les peuplades hunniques ne prouve rien. Il suffit de songer à l'exemple récent des Indiens d'Amérique qui ont su maîtriser à la perfection et très rapidement les chevaux européens capturés, après avoir été pris de panique en les apercevant pour la première fois. Pour prouver la fausseté de l'origine asiatique du cheval domestique, il suffit de signaler un fait : la civilisation chinoise, même arrivée à un degré de développement élevé, n'a appris à connaître le cheval que par l'intermédiaire de tribus indo-européennes orientales.

Si les Mongols ne sont pas les premiers domesticateurs du cheval, alors ce ne peuvent être que les Indo-Européens. Les traces de la plus ancienne domestication du cheval en Russie sont le fait d'Indo-Européens. L'opinion qui voulait attribuer une origine orientale au cheval domestique doit être reportée sur les Indo-Européens. À ce sujet, Franz Hancar (2), professeur à Vienne, avait dès 1955 débroussaillé le terrain et conforté l'origine européenne du cheval domestique. Le sort de ce travail de grande valeur a été tragique, car il a été publié à une époque où toutes les dates du néolithique européen avaient été erronément avancée de 2000 ans. Thenius, professeur de paléontologie, écrit dans un manuel publié à Vienne en 1969 : « Les chevaux ont été inclus dans l'oikos humain en Europe dès le néolithique. Un second centre de domestication a existé en Sibérie au 3ième millénaire av. notre ère » (3). Cette assertion, claire et succincte, n'est pas passée dans le grand public ni dans la recherche dominante actuelle en matières indo-européennes.

Bref résumé de l'histoire de la domestication

Examinons, au moins brièvement, les origines de la domestication des animaux. Les racines les plus anciennes des rapports entre l'homme et des mammifères, outre la chasse, remontent à la phase finale des hommes de Néanderthal, il y a 40.000 ans en Europe. L'image que l'on se faisait de cette sous-espèce (homo sapiens neanderthalensis) de l'homme accompli a radicalement changé au cours de ces cent dernières années : on avait cru qu'elle était à mi-chemin entre le singe et l'homme ; on sait désormais qu'elle était au moins égale au sapiens actuel et possédait un volume crânien plus important. Ces hommes ont laissé des autels de pierre dans les régions montagneuses de l'Europe centrale, sur lesquels étaient exposés des crânes et des fémurs d'ours des cavernes. Ce qui est important dans ce culte, c'est que les canines de ces crânes d'ours avaient été limées. Comme le prouve la présence d'une nouvelle couche d'émail, ces animaux ont vécu un certain temps sous la houlette de l'homme. Dans le Sud de la France (4), on a retrouvé trace d'une opération semblable sur des défenses de sanglier. Le culte de l'ours a été repris pas l'homo sapiens sapiens. Il s'est répandu à travers toute la Sibérie jusqu'à Hokaïdo, où des savants ont pu l'observer chez les Aïnous paléo-europides.

La domestication proprement dite commence avec celle du loup (canis lupus) en Eurasie septentrionale. L'ancienne hypothèse, qui postulait que la domestication découlait du fait que les loups suivaient les hommes, n'est plus défendue aujourd'hui par les biologistes. Nos ancêtres ne vivaient pas dans une société de gaspillage. Hommes et loups étaient d'âpres concurrents. La cause première de la domestication serait une superposition d'instincts. Les jeunes animaux déclenchent, via le schéma de l'enfant, l'instinct nourricier de l'homme ; le jeune animal, via le schéma de l'animal dominant dans le cadre des instincts grégaires, en vient à voir l'homme qui le soigne comme son dominant.

Le premier objectif de la domestication, c'est d'obtenir de la docilité par voie de sélection génétique. Le second objectif, c'est, au départ, d'obtenir une source de protéines et de matières grasses aisément accessible. Cela vaut pour toutes les phases premières de la domestication, du chien au cheval. Ce n'est que lorsque des cochons, des moutons et des chèvres domestiques ont été élevés que le chien a été réservé à d'autres tâches.

Chiens, cochons, moutons et chèvres

Les plus anciens ossements attestés de chiens domestiques (canis lupus f. familiaris) remontent à environ 8000 av. notre ère et ont été découverts dans le Yorkshire et dans le Senckenbergmoor (5). En 1986, j'ai pu prouver, grâce à un enchaînement d'indices, que déjà les chasseurs de mammouths il y a plus de 20.000 ans élevaient des chiens affublés de taches claires au-dessus des yeux (6). Les ossements les plus anciens de cochons domestiques (sus scrofa f. domestica) découverts jusqu'ici remontent à - 7500 et ont été découverts en Crimée. On remarquera que ces deux animaux domestiques n'impliquent aucunement la culture sur champ. Leurs éleveurs appartiennent encore au groupe linguistique boréen non fractionné tout en étant déjà les ancêtres des futurs Indo-Européens.

Dans la zone du Croissant fertile, l'agriculture commence vers -9000, de même que l'élevage des chèvres et des moutons. Les quatre espèces d'animaux domestiques sont des mammifères grégaires de taille moyenne. Ceux de la zone septentrionale sont omnivores ; ceux de la zone méridionale sont herbivores. Dès 1986, j'ai pu prouver, avec force arguments, que seuls le chien et le cochon étaient les premiers animaux domestiques des Indo-Européens. Une prière hittite-louvite le signale. En voici un extrait : « Dieu Soleil du ciel, mon seigneur, à l'enfant de l'homme, au chien, au cochon, à l'animal sauvage des champs, dites ce qui est juste, ô Dieu Soleil, dites-le jour après jour » (7).

Même si à l'époque de la transcription de cette prière, vers -1300, les Hittites, peuple indo-européens, disposent déjà d'un large éventail d'animaux domestiques, leur prière rappelle ce qu'il y avait avant. Dès 6000 av. notre ère, l'Europe et l'Orient s'étaient échangé leurs animaux domestiques. Mais jusqu'à ce jour, le chien et le cochon chez les Indo-Européens, le mouton et la chèvre chez les Hamito-Sémites, sont nettement privilégiés dans les cultes et dans les croyances populaires.

En Grèce, les Paléo-Egéens, qui, sur le plan linguistique, appartenaient probablement au groupe caucasien- anatolien, réussissent à domestiquer pour la première fois un mammifère de grande taille : le bœuf domestique (bos primigenius f. taurus). Cette performance mérite une ample attention, surtout si l'on songe combien dangereux peuvent encore être les taureaux et au rôle qu'a joué le bœuf dans l'alimentation de l'homme. Les recherches récentes relatives à la domestication ont découvert que la transformation physique la plus frappante dans la phase initiale de la domestication, c'est une diminution de la taille. On peut encore voir de très petits bovidés domestiques en Anatolie aujourd'hui.

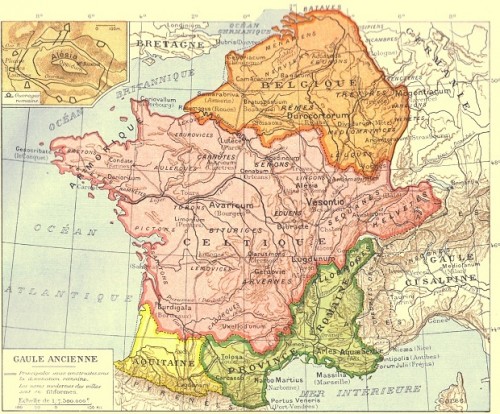

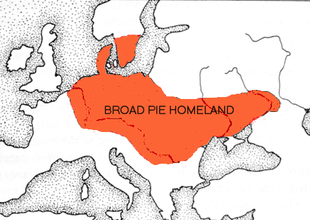

En Europe

Au nord des premiers éleveurs de bœufs, dans la péninsule balkanique, vivaient vers -6000, les porteurs de la culture des céramiques à bandeaux. Ils adoptent, en même temps que la culture des céréales, les animaux domestiques méditerranéens et transmettent ces formes d'économie à l'Europe Centrale en l'espace de 800 ans seulement. Il faut signaler dans ce processus trois stations de transmission au nord du cours supérieur du Danube pendant le néolithique : Müglitz/Mohelnice en Moravie ; Karbitz/Chabarovice en Bohème du Nord ; Olszanica en Haute-Silésie (8). Vers 5000 av. notre ère, la culture des céramiques à bandeaux linéaires s'étend déjà depuis l'Ouest de la France jusqu'à la Vistule. Les régions littorales du Nord et la Russie ne sont pas encore atteintes. Cela signifie que l'Europe du Sud-Est et du Centre possède à cette époque une avance culturelle et économique par rapport à toutes les autres régions du sous-continent.

Cette nouvelle forme d'économie provoque un premier mouvement de population, accompagné du défrichage par incendie et de la construction de maisons longues rectangulaires. Les haches perforées qui, dans le Nord de l'Europe préhistorique, étaient des haches faites en bois de cervidés et avaient déjà une longue tradition derrière elles, se fabriquent désormais en pierre taillée. Les morts sont enterrés assis. On reconnaît les tombes des hommes aux bijoux faits de fragments de coquilles d'huîtres. Le type racial dominant est est-méditerranéen. La taille des corps augmente en direction du nord, en concordance avec les lois de la zoologie. Les crânes hauts, étroits et longs se rapprochent de l'aspect de ceux des Est-nordides. Ce groupe démographiquement important et culturellement homogène pour les critères de cette lointaine époque ne peut qu'être indo-européen du point de vue linguistique. Vu les preuves nombreuses et les indices dont nous disposons, je ne puis que me référer à mon livre de 1986. Idem pour la justification exacte de la chronologie que j'emploie.

La capture des chevaux

À côté de l'élevage des animaux domestiques, la chasse continue à jouer un rôle important pour la satisfaction des besoins en protéines et en matières grasses. Le cheval sauvage est compris dans les animaux chassés, comme le prouvent les découvertes du Solutréen près de Lyon en France (28.000 - 17.000 av. notre ère). À cet endroit, les Paléo-Européens ouest-boréens ont tué quelque 40.000 à 100.000 chevaux en profitant de la panique de cet animal qui fuit devant le danger ; les chevaux tombaient du haut d'une falaise en fuyant. Ce cheval du Solutréen est, croit-on aujourd'hui, une forme primitive et occidentale du tarpan des forêts.

Si déjà les Paléo-Européens du Solutréen pouvaient organiser des chasses à battues efficaces, les représentants de la culture de la céramique en bandeaux devaient, eux aussi, en pratiquer. Grâce à leurs expériences acquises avec le bœuf domestique, ils savent comment s'y prendre avec les mammifères de grande taille. Dans les clairières, les lopins cultivés devaient immanquablement attirer les chevaux sauvages. D'après nos connaissances quant à la construction des bâtiments longitudinaux, il était possible de fabriquer des enclos vers lesquels on poussait les chevaux sauvages. De telles conditions n'existaient pas dans la steppe. De plus, même pour les représentants de la céramique à bandeaux linéaires, nous ne possédons pas encore de preuves de la domestication du cheval.

Les découvertes de Woldrich

Environ vers -4800, l'unité de la grande culture centre-européenne se fractionne. Dans le vieux centre que fut la Bohème et la Saxe, se développe une culture de la céramique à poinçon, qui dura jusque vers -4200. Tous les sites archéologiques démontrent qu'à cette époque, l'élevage des animaux joue un rôle beaucoup plus important. Mais il nous manque toujours des indices (des ossements en l'occurrence) prouvant une domestication du cheval. Dans un ancien rapport de fouilles, relatif au site de Karbitz/Aussig, le paléontologue J. Woldrich signale toutefois des données intéressantes quant à la présence d'ossements dans les fosses cultuelles de la culture des céramiques à bandeaux. À l'époque de Woldrich, les dénominations en zoologie pour les animaux domestiques n'étaient pas encore uniformes et l'âge de la culture n'était pas encore déterminé avec certitude. Je remarquai tout particulièrement que Woldrich signalait la présence de nombreux restes d'os d'equus caballus minor, puis de différents types de bovidés et aussi d'equus caballus. Ces noms d'espèce ne sont plus utilisés aujourd'hui. Mais ils correspondent à equus ferus = przewalskii, le cheval sauvage d'Eurasie. Nous venons de voir qu'il existait en Europe deux sous-espèces de cette espèce. Je tiens pour exclu que la désignation «minor» désigne le tarpan des forêts, plus petit et différent du tarpan des steppes. La région située entre les Monts Métallifères et les Monts de Bohème, à l'époque fort humide, était recouverte d'une épaisse forêt. Ce n'était pas du tout un espace adéquat pour le tarpan des steppes. De surcroît, les sous-espèces naturelles se sont précisément développées par isolation géographique. Souvenons-nous de cette connaissance, établie récemment, qui prouve que la taille moyenne des premiers animaux domestiqués diminuait par rapport à leur forme sauvage ; alors les descriptions de fouilles de Woldrich nous apparaissent sous un jour nouveau. À côté de quelques ossements de cheval sauvage (equus caballus ; dans la nomenclature moderne : e. f. = p.), Woldrich mentionne de très nombreux ossements de cheval domestique, qu'il nomme equus caballus minor (dans la nomenclature moderne : e. f. = p. f. caballus).

La découverte de mors

Mais pour les règles très sévères établies pour les recherches relatives à la domestication, les résultats de Woldrich ne sont pas suffisants pour servir de preuves. En revanche, il existe des découvertes provenant de sites relevant de la culture de la céramique à bandeaux poinçonnés, découvertes qui étayent mes interprétations de façon convaincante. Il s'agit de la découverte de deux mors de bridon. Déjà en 1907, on en avait découvert une paire en bois de cerf poli dans un habitat à Goldbach près d'Halberstadt. Ces pièces auraient disparu. Je possède toutefois la publication originale avec photo. Le deuxième bridon provient de Zauschwitz près de Pegau en Saxe et se trouve au Musée de Dresde (9).

La découverte de mors de bridon, c'est pour la problématique que nous soulevons, une preuve beaucoup plus intéressante que la découverte d'ossements. Dans la plupart des cas, les indices de la domestication d'un animal n'apparaissent sur le squelette qu'après plusieurs siècles d'élevage. De plus, nous savons que l'objectif premier de la domestication est d'obtenir une réserve alimentaire. Les mors de bridon prouvent néanmoins que le cheval domestique primitif, petit de taille et dérivant de la sous-espèce «tarpan des forêts», était déjà utilisé comme bête de somme. Tandis que les bœufs sont attelés au moyen d'un joug, aux chevaux, on mettait, à l'origine, un bridon léger en cuir. Celui-ci reposait sur l'espace sans dents, entre les incisives et les molaires et avait besoin de mors latéraux. Par l'intermédiaire de rênes, le cheval pouvait aussi être guidé depuis l'arrière. C'était un grand avantage pour le charriage de troncs d'arbre, pour tirer des objets ou des pièces ou pour les traîner sur la neige ou la glace. L'invention du mors et de la bride a été une condition indispensable à l'invention du char et pour les techniques de cavalerie, plus récentes encore.

On ne pouvait pas monter ces premiers et faibles petits chevaux domestiques. On ne peut conclure, au départ de ces premières tentatives d'attelage, que les Européens de cette époque possédaient déjà des véhicules à roues. Même à Sumer, beaucoup plus tard, vers 3500 av. notre ère ; on ne trouve que des traîneaux de bois, pas encore de chars à roues pleines. Ce que l'on peut concevoir de plus réaliste, c'est l'utilisation de traîneaux comme chez les Amérindiens et en Sibérie, où comme on l'a parfois revu en Europe récemment en période de détresse. Les traîneaux, pour les voyages sur glace ou sur neige, sont sans doute la deuxième étape dans les progrès de l'attelage. Quoi qu'il en soit, les indices récoltés dans les régions de Halberstadt, Pegau et Aussig proviennent du centre de la zone d'expansion des porteurs de la culture de la céramique à bandeaux et à poinçons, culture dans laquelle nous pouvons situer les plus anciens éleveurs indo-européens de chevaux.

Je voudrais brièvement rappeler ici que chez les porteurs de cette culture, on trouve, outre les haches de schiste en forme de semelles, des haches-marteaux à trous en pierre de roche. Mais la découverte la plus importante, après la domestication du cheval, se situe dans le domaine astronomique. À Leitmeritz, en Bohème du Nord, on a découvert une plaquette dans laquelle un calendrier lunaire avait été gravé (10). La disposition des traits gravés ressemble à un cercle de pieux de bois récemment découvert près de Quenstedt en Thuringe. Je rappelle au lecteur que, sur base de données établies grâce au C-14, nous nous trouvons entre -4800 et – 4200. À la même époque, les premiers mégalithes apparaissent en Bretagne et, en Bulgarie, les premiers rudiments de la métallurgie du cuivre et de l'or.

Le cheval comme animal domestique

La culture des céramiques à bandeaux et à poinçons a été remplacée par la culture des vases en entonnoirs (Trichterbecherkultur) ; le littoral de l'Allemagne du Nord et le Sud de la Scandinavie sont désormais inclus dans la zone néolithique agricole. À cela s'ajoute l'inhumation individuelle sous tumulus / kourgan, avec ou sans bords de pierre : c'est en dernière instance une caractéristique archéologique des Indo-Européens. Les tumuli du Groupe de Baalberg en Saxe/Thuringe sont plus anciens que les kourgans en bordure de la Mer Caspienne. Au cours de la phase des tombes à couloir (-3200/-2800), dans les habitats le long du Lac Dümmer (Basse-Saxe), le nombre d'ossements de chevaux dépasse largement celui de tous les animaux à sabots (11). Chez les porteurs contemporains dé la culture de Bernburg (sur le territoire de la RDA), on a recensé une paire de mors de bridon fait dans des défenses de sanglier à Warnstedt/Thale et des restes de crânes d'une race de petits chevaux domestiques près de Großquenstedt.

On a également trouvé à Jordansmühl en Silésie des inhumations de chevaux datant de -3600/3200 ; ces inhumations constituent les indices premiers d'une position cultuelle du cheval. Dans un site relevant de la culture de Baden en Basse-Autriche (-3200/-2800), on a retrouvé une pièce jugulaire en os provenant d'un mors. Le plus ancien point à l'Est, où l'on trouve trace d'une domestication du cheval, se situe en Ukraine occidentale. C'est dans cette région que la culture de Cucuteni-Tripolye, caractérisée par la présence de poteries peintes, a pris son envol à partir de -4200. Son origine doit être recherchée dans la plus ancienne des cultures de la céramique à bandeaux peinte dans les Balkans. Les ossements de chevaux domestiques sont déjà présents dans la phase de transition AB, laquelle commence vers ± -4000 ; on les retrouve à côté de traîneaux dans un territoire situé au Nord-Est de la zone de la culture de Tripolye. Parce qu'ils négligent les découvertes provenant des cultures plus anciennes de la céramique à bandeaux et à poinçons, les défenseurs de la thèse postulant une origine ouralienne des Indo-Européens affirment que ces vestiges constituent les preuves les plus anciennes de la domestication du cheval. Il est certain toutefois que les preuves les plus anciennes de la domestication du cheval entre 4800 et 3200 av. notre ère se limitent à l'espace entre le Lac Dümmer (Basse-Saxe) et le Dniepr.

L'apparition de la roue

Dès que l'élevage des chevaux se confirme, l'érection de tumuli s'étend à partir de -3800 depuis l'Ukraine occidentale jusqu'à l'espace sud-russe. Sur la base de signes écrits sumériens, on peut dater l'apparition des premières roues pleines en bois de -3300. D'après le tour de potier connu à Sumer depuis environ -4000, on pense que la roue est une invention des Sumériens. Même en tenant à cette théorie, on doit admettre qu'il soit étonnant que des roues pleines de bois, que l'on peut dater avec exactitude de -3000, aient été trouvées en Hollande et au Jutland, tandis que dès -3200 on trouve trace de massues cylindriques à l'époque des tombes à couloir de la culture des vases en entonnoir. Les massues cylindriques que j'ai pu observer ne présentent aucune trace d'usure prouvant qu'elles aient été utilisées. On peut évidemment penser qu'il s'agit de massues de cérémonie. Leur forme, présentant à l'évidence un moyeu affûté, correspond de manière frappante à des disques d'argile datant de la même époque et découverts en Hongrie. Dans ce site, on a également découvert un modèle miniature complet de char en argile datant d'environ -3000. Trois roues de bois bien conservées d'un diamètre variant entre 73 et 78 cm, trouvées près de Herning dans le Jutland, prouvent l'existence de chars dès -2800. Un char de la même époque a également été découvert dans le Sud de la Russie.

Le char, instrument de l'expansion indo-européenne

Dès que le char a été connu, il a dû se répandre en 300 ans de Sumer à l'Europe du Nord-Ouest. Le contact a dû indubitablement s'établir dans le Caucase. Les intermédiaires ont dû être ces Indo-Européens qui, à partir de -4200, ont quitté leur patrie originelle de l'Europe Centrale pour traverser l'Ukraine et buter contre les montagnes du Caucase. Dans les régions du Sud de la Russie, l'organisation économique se transforme : elle passe d'une structure de paysannerie nomade à l'élevage, avec une plus grande mobilité et une densité de population réduite. J'estime que c'est une erreur entachée d'idéologie de croire que ces tribus sont opposées et différentes, sur les plans de la langue et de la race, de leurs congénères paysans d'Europe Centrale. Hérodote nous rappelle pourtant que les Iraniens de son temps se répartissent en tribus d'élite paysannes et nomades. Sachons aussi que les farmers et les cow-boys d'Amérique représentent des types humains dérivés d'une même matrice, retrouvant sans doute les mêmes réflexes que leurs plus lointains ancêtres des steppes russo-ukrainiennes. D'après les preuves chronologiques que l'on a pu rassembler, les guerriers de l'Est, armés de haches de combat et dressant des tumuli pour leurs morts, ne sont ni les premiers Indo-Européens ni les inventeurs de la domestication du cheval. Ils sont certainement des Indo-Européens de la première heure, qui possédaient des chevaux et des chars ; ils ont assuré une diffusion rapide des ethnies et des langues indo-européennes de l'Atlantique à la Mer d'Aral.

Les Sumériens aux yeux bleus

J'aimerais évoquer encore le processus de transmission de la roue et signaler un état de choses que j'ai été le premier à mettre en évidence et à exploiter scientifiquement. On peut constater sur les reproductions photographiques de nombreux ouvrages illustrés que, dans le groupe de statuettes d'argile dit des «hommes en prière», ainsi que pour d'autres figures sumériennes, datant de -2700, un bon tiers des personnes représentées, appartenant aux castes supérieures ont un iris bleu incrusté en lapis-lazuli. Les deux autres tiers ont un iris brun. La pierre de couleur bleue devait être importée d'Afghanistan. Personne ne se serait donné tant de mal si des hommes aux yeux bleus étaient inconnus. Par hétérozygotie, ce gène récessif ne survient que dans le phénotype. Les mutants de cette caractéristique n'étaient pas installés au départ dans les zones subtropicale et centreasiatique. Les yeux bleus ne sont qu'un phénomène connexe sans valeur sélective naturelle dans le processus général d'éclaircissement des pigments. Les spécialistes ne s'entendent pas entre eux pour dire que les yeux bleus sont apparus au plus tard au début du néolithique en Europe centrale et en Europe du nord-ouest. Les éléments à yeux bleus dans les castes nobles de Sumer ne peuvent avoir immigré que d'une région située à l'Ouest. Lorsque je vis pour la première fois en 1979 la statuette du tronc d'un prince d'Ourouk, j'eus immédiatement l'impression d'avoir en face de moi un conducteur de char. Archéologues et historiens de l'art ne pourront jamais expliquer la position des mains, s'ils persistent à croire que ce prince est en prière. Plus tard, je pus apprendre, dans la Propyläen-Kunstgeschichte, que dans les orbites de cette figure, de 500 ans plus ancienne, on a découvert des restes de lapis-lazuli dans un noyau en coquillage blanc (12).

Grâce à cette découverte, je me suis convaincu que dès -3200 une première caste de conducteurs de chars a déboulé en Orient, exactement de la même façon que vers -1650 les Mitanniens indoaryens surgiront en Syrie. Évidemment, il s'agissait encore de chars primitifs, dotés de roues de bois pleines, dont les chevaux n'étaient encore guère accoutumés au climat subtropical. Pour cette raison, ces tribus attelèrent des onagres. Mais il est possible de parler dès cette époque d'un contact culturel reliant Sumer à la Mer du Nord.

Peu après apparaissent également de riches tumuli érigés par des Indo-Européens orientaux dans la région du Kouban. À partir de cette région, des tribus s'élancent vers la Sibérie et vers l'Altaï, où se crée alors, au IIIième millénaire av. notre ère, un second centre de domestication du cheval. Déjà en Russie, l'espèce, de taille plus grande, qu'est le tarpan des steppes, s'était croisée avec le cheval domestique. Aux temps historiques, les étalons tarpans séduisaient et enlevaient des juments domestiques, ce qui a conduit, au siècle passé, à l'extermination des derniers tarpans de Russie. Le tarpan oriental a pu se croiser en Mongolie avec des chevaux domestiqués. En Europe les chevaux de fjord norvégiens constituent les derniers vestiges d'une forme ancienne de cheval domestique retournée à l'état sauvage et dérivée du tarpan des forêts. Ces chevaux sont toutefois plus forts et capables de meilleures prestations que les premiers chevaux domestiques.

Les racines linguistiques des mots signifiant «chevaux»

En langue indo-européenne primitive, le mot commun pour désigner le cheval est *ekvos. En tokharien, il prend la forme de yakvé et celle-ci se retrouve jusqu'en Chine. Chez les Indo-aryens, le mot devient asva, à cause de la mutation consonantique qui transforme le k en s. La mutation iranienne, laquelle se retrouve également dans les nom de personnes en Thrace, donne aspa. Les Illyriens et les Celtes, originaires d'Europe Centrale, transforment le groupe consonantique kv en p. C'est ainsi que le constructeur du Cheval de Troie se nomme Épeios et que la déesse chevaline gauloise s'appelle Épona. Cette forme s'est maintenue dans certains dialectes allemands et en grec ancien. Le terme allemand Mähre, que l'on retrouve dans le vocable péjoratif Schindmähre (rosse, carne), est dérivé du vieil-haut-allemand merila, signifiant jument. La racine de ce mot est mongole (*mörin). On peut penser que ce sont les Huns qui nous l'ont transmis. Le mot Pferd (nl : paard) dérive, quant à lui, du moyen-latin paraveredus, qui désignait les chevaux de la poste gallo-romaine. Le mot ouralique *kaväl nous est venu d'Asie centrale via le finnois et le slave. L'origine de *kob-moni n'est pas encore tout à fait élucidée. De ce mot dérive le terme greco-latin kaballe/us, que l'on retrouve â côté de hippos et equus. Nous l'avons conservé dans les mots français «cavalier» (Kavalier) et «cavalerie» (Kavallerie). La racine *mandus est westique-méditerranéenne : on la retrouve chez les Basques et les Étrusques. Celtes et Italiques utilisent le mot mannus pour désigner le poney.

Friedrich Cornelius (13) fut le premier à remarquer que la plus ancienne preuve onomastique d'une invasion venue de l'Ouest à Akkad en Mésopotamie date de -2270, sous le règne de Naramsin. Il s'agit des Erin Manda, guerriers montés sur chars appartenant très certainement au groupe des Hittites-Louvites. Ceux-ci avaient pénétré en Anatolie centrale et méridionale via Troie. C'est à eux que l'on doit l'invention du char à deux roues, lesquelles sont à rayons en bois de frêne. Mandus est ici la désignation particulière du cheval des chars. Les Hittites, au plus tard vers -1700, avaient mis sur pied des corps d'armée puissants montés sur des chars de combat et de chasse. Une organisation semblable se retrouve également chez la noblesse guerrière indo-aryenne des Hourrites. À côté de noms de dieux, on trouve des expressions propres au dressage des chevaux parmi les vocables découverts sur documents écrits et relevant des Aryens au temps où ils vivaient non encore divisés en Asie Mineure.

Assyriens, Babyloniens et Égyptiens adoptent le cheval

En Grèce et dans la culture nordique de Scandinavie, le char léger de combat est attesté par des représentations depuis -1600 au moins. Très rapidement les Assyriens, les Babyloniens et les Égyptiens, sous l'influence des Kassites et des Hyksos, s'approprient la nouvelle arme. En Égypte, les dynasties d'après la libération des dominations étrangères sont très clairement marquées par les idéaux des guerriers charistes. Les femmes des pharaons et leurs suites, composées d'une noblesse aryenne-hourritique, ont certainement renforcer la tendance.

Il n'est pas étonnant que la toute première représentation égyptienne d'un véritable cavalier au milieu de guerriers dans un camp de campagne date de -1325 (18ième Dynastie). Le cheval y est fringant et bridé ; le cavalier ne dispose pas de selle et est nu. Il s'agit peut-être d'un cheval de char mené à l'abreuvoir. Cornelius croit que l'origine de la cavalerie proprement dite (sans char) doit être recherchée chez les Amazones de l'Anatolie du nord-ouest. Il s'agirait de femmes originaires du pays d'Adzzi et des localités d'Amisos, d'Amasia et Amastris (Am- désignant «femme»). Par une étymologie vulgaire et erronée, les Grecs en auraient fait a-mazi, c'est-à-dire guerrières sans seins. D'après Cornelius (14), ce serait ces femmes-là qui seraient les inventeurs de la cavalerie vers -1230. Dans l'Empire des Hittites, on ne montait les chevaux que pour les dresser à tracter des chars de course. D'après des gravures rupestres de Suède, Spanuth date trop tôt (de 200 ans) les premiers cavaliers, avec boucliers rectangulaires. Ce n'est pas avant -1200 que les guerriers cavaliers apparaissent simultanément en Europe, en Orient et en Sibérie.

Se représenter des Indo-Européens primitifs cavaliers venus de l'Est est donc une aberration. Car au moment de l'apparition du char léger de combat vers -2300, l'unité linguistique indo-européenne n'existait déjà plus. Mais chez tous les Indo-Européens, qui descendent des plus anciens paysans d'Europe Centrale, on trouve une croyance commune : le dieu solaire est tiré le jour par un couple de chevaux. Dans le char solaire de Trundholm, cette croyance est illustrée par l'une des plus belles pièces d'art de la «préhistoire». En tant qu'Alces chez les Germains de l'Âge du Bronze, qu'Asvin chez les Aryens et que les Dioscures chez les Grecs et les Romains, le divin attelage chevalin a été personnifié. Les jumeaux divins aident les guerriers, les naufragés et les femmes qui accouchent dans la détresse. À partir de -1380, à l'époque de la culture des champs d'urnes, la représentation du char solaire se couple au culte des cygnes. C'est pourquoi des têtes de chevaux et de cygnes ornent les étraves des bateaux scandinaves depuis l'Âge du Bronze.

Le cheval domestique, dressé par les Indo-Européens, est devenu l'animal le plus important de toute l'histoire mondiale.

► Wilfried Peter Adalbert FISCHER, Vouloir n°52/53, 1989.

(texte issu de Deutschland in Geschichle und Gegenwart, 36. Jg., Nr. 4, 1988 ; adresse : Grabert-Verlag, Am Apfelberg 18, Postfach 1629, D-7400 Tübingen 1.Trad. française : R. Steuckers).

Wilfried Peter A. FISCHER, Alteuropa in neuer Sicht : Ein interdisziplinärer Versuch zu Ursprung und Leistung der Indoeuropäer, LIT Verlag, Münster, 1986, 300 S., DM 58 ; adresse : Dieckstr. 56, D-4400 Münster, tel. : (0251) 23.19.72.

La richesse de cet ouvrage est impressionnante : Fisher nous y initie à l'archéologie préhistorique, à la linguistique, à la raciologie. Son livre complète utilement les recherches des instituts américain (Journal of Indo-European Studies) et français (Institut d'Études indo-européennes de l'Université de Lyon 3) des professeurs Marija Gimbutas, Jean-Paul Allard, Jean Haudry et Jean Varenne. Nous le recommandons chaleureusement.

Notes

(1) Wolf Herre u. Manfred Röhrs, Haustiere - zoologisch gesehen, Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart, 1973, S. 29. (2) Franz Hancar, Das Pferd in prähistorischer und früher historischer Zeit, Verlag Herold, Wien/München, 1956.

(3) Erich Thenius, Phylogenie der Mammalia, Walter de Gruyter & Co., Berlin, 1969, S. 565.

(4) Burchard Brentjes, Die Haustierwerdung im Orient, Franckh'sche Verlagshandlung, Stuttgart, 1965, S.10. (5) Wilfried Peter A. Fischer, Alteuropa in neuer Sicht, Lit Verlag, Münster, 1986, S. 35.

(6) Ibid., S.36f.

(7) Ibid., S.138.

(8) David u. Ruth Whitehouse, Lübbes archäologischer Weltatlas, Gustav Lübbe Verlag, Bergisch Gladbach, 1976, S. 134.

(9) WPA Fischer, op. cit., S. 72.

(10) Ibid., S. 238.

(11) Ibid., S. 36.

(12) Ibid., S. 136. D’après Marin Dinn, dans une thèse publiée en 1981, on trouve des modèles de roues de char en Roumanie dès -4200. Ces modèles sont donc plus anciens que ceux de Sumer, ce qui étaye mes considérations à propos des conducteurs de chars à yeux bleus.

(13) Friedrich Cornelius, Geschichte der Hethiter, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt, 1976.

(14) Ibid., S. 269 ff.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Spanuth's approach to Atlantis was professional, as a classical scholar he had access to many ancient inscriptions, writings and fragments (especially Greek) and his expertise in this field meant he could quote and examine them in great detail. His original book 'Atlantis the mystery unravelled' was the most comprehenesive containing a massive amount of referenced classical sources. The purpose of Atlantis of the North (as the introduction states on the first few pages) was merely to be a ''shorter version'' of the original, for better access and understanding for the reader. There are still hundreds of classical sources however found cited throughout the book.

Spanuth's approach to Atlantis was professional, as a classical scholar he had access to many ancient inscriptions, writings and fragments (especially Greek) and his expertise in this field meant he could quote and examine them in great detail. His original book 'Atlantis the mystery unravelled' was the most comprehenesive containing a massive amount of referenced classical sources. The purpose of Atlantis of the North (as the introduction states on the first few pages) was merely to be a ''shorter version'' of the original, for better access and understanding for the reader. There are still hundreds of classical sources however found cited throughout the book.

Los primeros hombres, con ojos de color de cielo y cabellos de color de luz, engastaron en sus dagas de sílex la Piedra de Luna… pusieron en movimiento las aspas del sol y se adueñaron de la Tierra por añadidura. Buscaban Avalón en este mundo y la Piedra de Luna tuvo para ellos significado diferente. El Guía fue el primer Caminante de la Aurora y su nombre cambia en las Edades. La Piedra de Luna estuvo entre sus cejas. La daga de sílex en sus manos. La Tierra bajo sus plantas. La piel del Carnero fue el emblema que se mecía al viento de esas edades.

Los primeros hombres, con ojos de color de cielo y cabellos de color de luz, engastaron en sus dagas de sílex la Piedra de Luna… pusieron en movimiento las aspas del sol y se adueñaron de la Tierra por añadidura. Buscaban Avalón en este mundo y la Piedra de Luna tuvo para ellos significado diferente. El Guía fue el primer Caminante de la Aurora y su nombre cambia en las Edades. La Piedra de Luna estuvo entre sus cejas. La daga de sílex en sus manos. La Tierra bajo sus plantas. La piel del Carnero fue el emblema que se mecía al viento de esas edades.

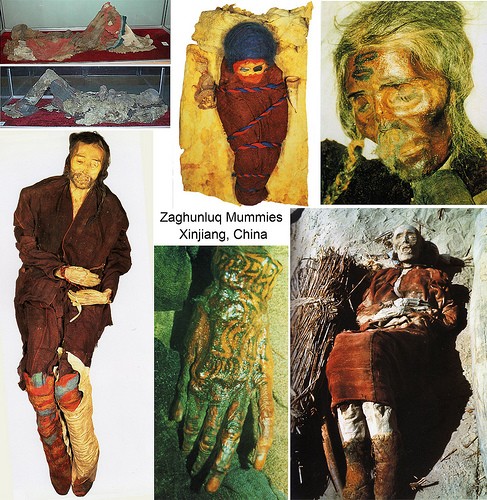

Eu estava, pois, apoiado no bar, bebericando um xarope de romã, quando vi avançar na minha direção um homenzinho calvo com alguns fios longos ao redor das orelhas; visivelmente ele tinha vontade de debater, pouco importando o assunto; nós bebemos e ele falou; ou o contrário; ele tinha um velho sobretudo negro, cujas manchas eram muito grandes, óculos que eram verdadeiros binóculos e se exprimia com um sotaque curioso, que enrolava os “r”, vindo talvez de qualquer parte do leste. Uma mistura de professor Girassol com Bergier. Ele me contou uma história engraçada sobre múmias que foram descobertas na China em um deserto, múmias de “gigantes loiros”, dizia. Ele desapareceu no momento em que eu pagava a conta; eu me perguntei se ele não era uma aparição, de um ou de outro dos personagens anteriormente citados; sim, eu sei que o professor Girassol não existe que sob o lápis de Hergé, mas sabe-se lá. Paul-Georges Sansonetti deve saber. Eu havia esquecido esta história até os dias de hoje, quando eu fiz algumas pesquisas. Somente para saber que o homenzinho não brincava.

Eu estava, pois, apoiado no bar, bebericando um xarope de romã, quando vi avançar na minha direção um homenzinho calvo com alguns fios longos ao redor das orelhas; visivelmente ele tinha vontade de debater, pouco importando o assunto; nós bebemos e ele falou; ou o contrário; ele tinha um velho sobretudo negro, cujas manchas eram muito grandes, óculos que eram verdadeiros binóculos e se exprimia com um sotaque curioso, que enrolava os “r”, vindo talvez de qualquer parte do leste. Uma mistura de professor Girassol com Bergier. Ele me contou uma história engraçada sobre múmias que foram descobertas na China em um deserto, múmias de “gigantes loiros”, dizia. Ele desapareceu no momento em que eu pagava a conta; eu me perguntei se ele não era uma aparição, de um ou de outro dos personagens anteriormente citados; sim, eu sei que o professor Girassol não existe que sob o lápis de Hergé, mas sabe-se lá. Paul-Georges Sansonetti deve saber. Eu havia esquecido esta história até os dias de hoje, quando eu fiz algumas pesquisas. Somente para saber que o homenzinho não brincava. É o turcólogo alemão F.W. K. Muller quem deu, em 1907, o nome de tokariana a uma língua que nós podemos decifrar facilmente nos manuscritos, pois eles estavam anotados de maneira bilíngüe tokariano – sânscrito. Os lingüistas teriam em seguida estabelecido os vínculos entre esta língua e as línguas indo-européias, essencialmente o celta e o germânico. Nós reencontraremos alguma sonoridade similar nestes exemplos, respectivamente em português², francês, latim, irlandês e tokariano: mãe, mère, mater, mathir, macer. Irmão, frère, frater, brathir, prócer (próximo do inglês “brother”), três, trois, tres, tri, tre (segundo Giovanni Monastra).

É o turcólogo alemão F.W. K. Muller quem deu, em 1907, o nome de tokariana a uma língua que nós podemos decifrar facilmente nos manuscritos, pois eles estavam anotados de maneira bilíngüe tokariano – sânscrito. Os lingüistas teriam em seguida estabelecido os vínculos entre esta língua e as línguas indo-européias, essencialmente o celta e o germânico. Nós reencontraremos alguma sonoridade similar nestes exemplos, respectivamente em português², francês, latim, irlandês e tokariano: mãe, mère, mater, mathir, macer. Irmão, frère, frater, brathir, prócer (próximo do inglês “brother”), três, trois, tres, tri, tre (segundo Giovanni Monastra).