dimanche, 08 juillet 2012

American Transcendentalism

American Transcendentalism:

An Indigenous Culture of Critique

By Kevin MacDonald

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Philip F. Gura

Philip F. Gura

American Transcendentalism: A History [2]

New York: Hill and Wang, 2007

Philip Gura’s American Transcendentalism provides a valuable insight into a nineteenth-century leftist intellectual elite in the United States. This is of considerable interest because Transcendentalism was a movement entirely untouched by the predominantly Jewish milieu of the twentieth-century left in America. Rather, it was homegrown, and its story tells us much about the sensibility of an important group of white intellectuals and perhaps gives us hints about why in the twentieth century WASPs so easily capitulated to the Jewish onslaught on the intellectual establishment.

Based in New England, Transcendentalism was closely associated with Harvard and Boston—the very heart of Puritan New England. It was also closely associated with Unitarianism which had become the most common religious affiliation for Boston’s elite. Many Transcendentalists were Unitarian clergymen, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, the person whose name is most closely associated with the movement in the public mind.

These were very intelligent people living in an age when religious beliefs required an intellectual defense rather than blind acceptance. Their backgrounds were typical of New England Christians of the day. But as their intellectual world expanded (often at the Harvard Divinity School), they became aware of the “higher criticism” of the Bible that originated with German scholars. This scholarship showed that there were several different authors of Genesis and that Moses did not write the first five books of the Old Testament. They also became aware of other religions, such as Buddhism and Hinduism which made it unlikely that Christianity had a monopoly on religious truth.

In their search for an intellectual grounding of religion, they rejected Locke’s barren empiricism and turned instead to the idealism of Kant, Schelling, and Coleridge. If the higher criticism implied that the foundations of religious belief were shaky, and if God was unlikely to have endowed Christianity with unique religious truths, the Transcendentalists would build new foundations emphasizing the subjectivity of religious experience. The attraction of idealism to the Transcendentalists was its conception of the mind as creative, intuitive, and interpretive rather than merely reactive to external events. As the writer and political activist Orestes Brownson summed it up in 1840, Transcendentalism defended man’s “capacity of knowing truth intuitively [and] attaining scientific knowledge of an order of existence transcending the reach of the senses, and of which we can have no sensible experience” (p. 121). Everyone, from birth, possesses a divine element, and the mind has “innate principles, including the religious sentiment” (p. 84).

The intuitions of the Transcendentalists were decidedly egalitarian and universalist. “Universal divine inspiration—grace as the birthright of all—was the bedrock of the Transcendentalist movement” (p. 18). Ideas of God, morality, and immortality are part of human nature and do not have to be learned. As Gura notes, this is the spiritual equivalent of the democratic ideal that all men (and women) are created equal.

Intuitions are by their very nature slippery things. One could just as plausibly (or perhaps more plausibly) propose that humans have intuitions of greed, lust, power, and ethnocentrism—precisely the view of the Darwinians who came along later in the century. In the context of the philosophical milieu of Transcendentalism, their intuitions were not intended to be open to empirical investigation. Their truth was obvious and compelling—a fact that tells us much about the religious milieu of the movement.

On the other hand, the Transcendentalists rejected materialism with its emphasis on “facts, history, the force of circumstance and the animal wants of man” (quoting Emerson, p. 15). Fundamentally, they did not want to explain human history or society, and they certainly would have been unimpressed by a Darwinian view of human nature that emphasizes such nasty realities as competition for power and resources and how these play out given the exigencies of history. Rather, they adopted a utopian vision of humans as able to transcend all that by means of the God-given spiritual powers of the human mind.

Not surprisingly, this philosophy led many Transcendentalists to become deeply involved in social activism on behalf of the lower echelons of society—the poor, prisoners, the insane, the developmentally disabled, and slaves in the South.

* * *

The following examples give a flavor of some of the central attitudes and typical social activism of important Transcendentalists.

Orestes Brownson (1803–1876) admired the Universalists’ belief in the inherent dignity of all people and the promise of eventual universal salvation for all believers. He argued “for the unity of races and the inherent dignity of each person, and he lambasted Southerners for trying to enlarge their political base” (p. 266). Like many New Englanders, he was outraged by the Supreme Court decision in the Dred Scott case that required authorities in the North to return fugitive slaves to their owners in the South. For Brownson the Civil War was a moral crusade waged not only to preserve the union, but to emancipate the slaves. Writing in 1840, Brownson claimed that we should “realize in our social arrangements and in the actual conditions of all men that equality of man and man” that God had established but which had been destroyed by capitalism (pp. 138–39). According to Brownson, Christians had

to bring down the high, and bring up the low; to break the fetters of the bound and set the captive free; to destroy all oppression, establish the reign of justice, which is the reign of equality, between man and man; to introduce new heavens and a new earth, wherein dwelleth righteousness, wherein all shall be as brothers, loving one another, and no one possessing what another lacketh. (p. 139)

George Ripley (1802–1880), who founded the utopian community of Brook Farm and was an important literary critic, “preached in earnest Unitarianism’s central message, a belief in universal, internal religious principle that validated faith and united all men and women” (p. 80). Ripley wrote that Transcendentalists “believe in an order of truths which transcends the sphere of the external senses. Their leading idea is the supremacy of mind over matter.” Religious truth does not depend on facts or tradition but

has an unerring witness in the soul. There is a light, they believe, which enlighteneth every man that cometh into the world; there is a faculty in all, the most degraded, the most ignorant, the most obscure, to perceive spiritual truth, when distinctly represented; and the ultimate appeal, on all moral questions, is not to a jury of scholars, a hierarchy of divines, or the prescriptions of a creed, but to the common sense of the race. (p. 143)

Ripley founded Brook Farm on the principle of substituting “brotherly cooperation” for “selfish competition” (p. 156). He questioned the economic and moral basis of capitalism. He held that if people did the work they desired, and for which they had a talent, the result would be a non-competitive, classless society where each person would achieve personal fulfillment.

Amos Bronson Alcott (1799–1888) was an educator who “believed in the innate goodness of each child whom he taught” (p. 85). Alcott “realized how Unitarianism’s positive and inclusive vision of humanity accorded with his own” (p. 85). He advocated strong social controls in order to socialize children: infractions were reported to the entire group of students, which then prescribed the proper punishment. The entire group was punished for the bad behavior of a single student. His students were the children of the intellectual elite of Boston, but his methods eventually proved unpopular. The school closed after most of the parents withdrew their children when Alcott insisted upon admitting a black child. Alcott supported William Garrison’s radical abolitionism, and he was a financial supporter of John Brown and his violent attempts to overthrow slavery.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882) stirred a great deal of controversy in his American Scholar, an 1832 address to the Harvard Divinity School, because he reinterpreted what it meant for Christ to claim to be divine:

One man was true to what is in you and me. He saw that God incarnates himself in man, and evermore goes forth to take possession of his world. He said, in this jubilee of sublime emotion, “I am divine. Through me, God acts; through me, he speaks. Would you see God, see me; or, see thee, when thou also thinkest as I now think.” (p. 103)

Although relatively individualistic by the standards of Transcendentalism, Emerson proposed that by believing in their own divine purpose, people would have the courage to stand up for social justice. The divinely powered individual was thus linked to disrupting the social order.

Theodore Parker (1810–1860) was a writer, public intellectual, and model for religiously motivated liberal activism. He wrote that “God is alive and in every person” (p. 143). Gura interprets Parker as follows: “God is not what we are, but what we need to make our lives whole, and one way to realize this is through selfless devotion to God’s creation” (p. 218).

Parker was concerned about crime and poverty, and he was deeply opposed to the Mexican war and to slavery. He blamed social conditions for crime and poverty, condemning merchants: “We are all brothers, rich and poor, American and foreign, put here by the same God, for the same end, and journeying towards the same heaven, and owing mutual help” (p. 219). In Parker’s view, slavery is “the blight of this nation” and was the real reason for the Mexican war, because it was aimed at expanding the slave states. Parker was far more socially active than Emerson, becoming one of the most prominent abolitionists and a secret financial supporter of John Brown.

When Parker looked back on the history of the Puritans, he saw them as standing for moral principles. He approved in particular of John Eliot, who preached to the Indians and attempted to convert them to Christianity.

Nevertheless, Parker is a bit of an enigma because, despite being a prominent abolitionist and favoring racial integration of schools and churches, he asserted that the Anglo-Saxon race was “more progressive” than all others.[1] He was also prone to making condescending and disparaging comments about the potential of Africans for progress.

William Henry Channing (1810–1884) was a Transcendentalist writer and Christian socialist. He held that economic activity conducted in the spirit of Christian love would establish a more egalitarian society that would include immigrants, the poor, slaves, prisoners, and the mentally ill. He worked tirelessly on behalf of the cause of emancipation and in the Freedman’s Bureau designed to provide social services for former slaves. Although an admirer of Emerson, he rejected Emerson’s individualism, writing in a letter to Theodore Parker that it was one of his deepest convictions that the human race “is inspired as well as the individual; that humanity is a growth from the Divine Life as well as man; and indeed that the true advancement of the individual is dependent upon the advancement of a generation, and that the law of this is providential, the direct act of the Being of beings.”[2]

* * *

In the 1840s there was division between relatively individualist Trancendentalists like Emerson who “valued individual spiritual growth and self-expression,” and “social reformers like Brownson, Ripley, and increasingly, Parker” (p. 137). In 1844 Emerson joined a group of speakers that included abolitionists, but many Transcendentalists questioned his emphasis on self-reliance given the Mexican war, upheaval in Europe, and slavery. They saw self-reliance as ineffectual in combating the huge aggregation of interests these represented. Elizabeth Peabody lamented Emerson’s insistence that a Transcendentalist should not labor “for small objects, such as Abolition, Temperance, Political Reforms, &c.” (p. 216). (She herself was an advocate of the Kindergarten movement as well as Native American causes [p. 270].)

But Emerson did oppose slavery. An 1844 speech praised Caribbean blacks for rising to high occupations after slavery: “This was not the case in the United States, where descendants of Africans were precluded any opportunity to be a white person’s equal. This only reflected on the moral bankruptcy of American white society, however, for ‘the civility of no race can be perfect whilst another race is degraded’” (p. 245).

Emerson and other Transcendentalists were outraged by the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. Gura notes that for Emerson, “the very landscape seemed robbed of its beauty, and he even had trouble breathing because of the ‘infamy’ in the air” (p. 246). After the John Brown debacle, Emerson was “glad to see that the terror at disunion and anarchy is disappearing,” for the price of slaves’ freedom might demand it (p. 260). Both Emerson and Thoreau commented on Brown’s New England Puritan heritage. Emerson lobbied Lincoln on slavery, and when Lincoln emancipated the slaves, he said “Our hurts are healed; the health of the nation is repaired” (p. 265). He thought the war worth fighting because of it.

* * *

After the Civil War, idealism lost its preeminence, and American intellectuals increasingly embraced materialism. Whereas Locke had been the main inspiration for materialism earlier in the century, materialism was now exemplified by Darwin, Auguste Comte, and William Graham Sumner. After the Civil War, the Transcendentalists’ contributions to American intellectual discourse “remained vital, if less remarked, particularly among those who kept alive a dream of a common humanity based in the irreducible equality of all souls” (p. 271). One of the last Transcendentalists, Octavius Brooks Frothingham, wrote that Transcendentalism was being “suppressed by the philosophy of experience, which, under different names, was taking possession of the speculative world” (p. 302). The enemies of Transcendentalism were “positivists” (p. 302). After Emerson’s death, George Santayana commented that he “was a cheery, child-like soul, impervious to the evidence of evil” (pp. 304–305).

By the early twentieth century, then, Transcendentalism was a distant memory, and the new materialists had won the day. The early part of the twentieth century was the high water mark of Darwinism in the social sciences. It was common at that time to think that there were important differences between the races in both intelligence and moral qualities. Not only did races differ, they were in competition with each other for supremacy. Whereas later in the century, Jewish intellectuals led the battle against Darwinism in the social sciences, racialist ideas were part of the furniture of intellectual life—commonplace among intellectuals of all stripes, including a significant number of Jewish racial nationalists concerned about the racial purity and political power of the Jewish people.[3]

The victory of Darwinisn was short-lived, however, as the left became reinvigorated by the rise of several predominantly Jewish intellectual and political movements: Marxism, Boasian anthropology, psychoanalysis, and other ideologies that collectively have dominated intellectual discourse ever since.[4]

* * *

So what is one to make of this prominent strand of egalitarian universalism in nineteenth-century America? The first thing that strikes one about Transcendentalism is that it is an outgrowth of the Puritan strain of American culture. Transcendentalism was centered in New England, and all its major figures were descendants of the Puritans. I have written previously of Puritanism as a rather short-lived group evolutionary strategy, supplementing the work of David Sloan Wilson on Calvinism, the forerunner of Puritanism.[5] The basic idea is that, like Jews, Puritans during their heyday had a strong psychological sense of group membership combined with social controls that minutely regulated the behavior of ingroup members. Their group strategy depended on being able to control a particular territory—Massachusetts—but by the end of theseventeenth century, they were unable to regulate the borders of the colony due to the policy of the British colonial authorities, hence the government of Massachusetts ceased being the embodiment of the Puritans as a group. In the absence of political control, Puritanism gradually lost the power to enforce its religious strictures (e.g., church attendance and orthodox religious beliefs), and the population changed as the economic prosperity created by the Puritans drew an influx of non-Puritans into the area.

The Puritans were certainly highly intelligent, and they sought a system of beliefs that was firmly grounded in contemporary thinking. One striking aspect of Gura’s treatment is his description of earnest proto-Transcendentalists trekking over to Germany to imbibe the wisdom of German philosophy and producing translations and lengthy commentaries on this body of work for an American audience.

But the key to Puritanism as a group strategy, like other strategies, was the control of behavior of group members. As with Calvin’s original doctrine, there was a great deal of supervision of individual behavior. Historian David Hackett Fischer describes Puritan New England’s ideology of “Ordered Liberty” as “the freedom to order one’s acts in a godly way—but not in any other.”[6] This “freedom as public obligation” implied strong social control of thought, speech, and behavior.

Both New England and East Anglia (the center of Puritanism in England) had the lowest relative rates of private crime (murder, theft, mayhem), but the highest rates of public violence—“the burning of rebellious servants, the maiming of political dissenters, the hanging of Quakers, the execution of witches.”[7] This record is entirely in keeping with Calvinist tendencies in Geneva.[8]

The legal system was designed to enforce intellectual, political, and religious conformity as well as to control crime. Louis Taylor Merrill describes the “civil and religious strait-jacket that the Massachusetts theocrats applied to dissenters.”[9] The authorities, backed by the clergy, controlled blasphemous statements and confiscated or burned books deemed to be offensive. Spying on one’s neighbors and relatives was encouraged. There were many convictions for criticizing magistrates, the governor, or the clergy. Unexcused absence from church was fined, with people searching the town for absentees. Those who fell asleep in church were also fined. Sabbath violations were punished as well. A man was even penalized for publicly kissing his wife as he greeted her on his doorstep upon his return from a three-year sea voyage.

Kevin Phillips traces the egalitarian, anti-hierarchical spirit of Yankee republicanism back to the settlement of East Anglia by Angles and Jutes in post-Roman times.[10] They produced “a civic culture of high literacy, town meetings, and a tradition of freedom,” distinguished from other British groups by their “comparatively large ratios of freemen and small numbers of servi and villani.”[11] President John Adams cherished the East Anglian heritage of “self-determination, free male suffrage, and a consensual social contract.”[12] East Anglia continued to produce “insurrections against arbitrary power”—the rebellions of 1381 led by Jack Straw, Wat Tyler, and John Ball; Clarence’s rebellion of 1477; and Robert Kett’s rebellion of 1548. All of these rebellions predated the rise of Puritanism, suggesting an ingrained cultural tendency.

This emphasis on relative egalitarianism and consensual, democratic government are tendencies characteristic of Northern European peoples as a result of a prolonged evolutionary history as hunter-gatherers in the north of Europe.[13] But these tendencies are certainly not center stage when thinking about the political tendencies of the Transcendentalists.

What is striking is the moral fervor of the Puritans. Puritans tended to pursue utopian causes framed as moral issues. They were susceptible to appeals to a “higher law,” and they tended to believe that the principal purpose of government is moral. New England was the most fertile ground for “the perfectibility of man creed,” and the “father of a dozen ‘isms.’”[14] There was a tendency to paint political alternatives as starkly contrasting moral imperatives, with one side portrayed as evil incarnate—inspired by the devil.

Whereas in the Puritan settlements of Massachusetts the moral fervor was directed at keeping fellow Puritans in line, in the nineteenth century it was directed at the entire country. The moral fervor that had inspired Puritan preachers and magistrates to rigidly enforce laws on fornication, adultery, sleeping in church, or criticizing preachers was universalized and aimed at correcting the perceived ills of capitalism and slavery.

Puritans waged holy war on behalf of moral righteousness even against their own cousins—perhaps a form of altruistic punishment as defined by Ernst Fehr and Simon Gächter.[15] Altruistic punishment refers to punishing people even at a cost to oneself. Altruistic punishment is found more often among cooperative hunter-gatherer groups than among groups, such as Jews, based on extended kinship.[16]

Whatever the political and economic complexities that led to the Civil War, it was the Yankee moral condemnation of slavery that inspired and justified the massive carnage of closely related Anglo-Americans on behalf of slaves from Africa. Militarily, the war with the Confederacy was the greatest sacrifice in lives and property ever made by Americans.[17] Puritan moral fervor and punitiveness are also evident in the call of the Congregationalist minister at Henry Ward Beecher’s Old Plymouth Church in New York during the Second World War for “exterminating the German people . . . the sterilization of 10,000,000 German soldiers and the segregation of the woman.”[18]

It is interesting that the moral fervor the Puritans directed at ingroup and outgroup members strongly resembles that of the Old Testament prophets who railed against Jews who departed from God’s law, and against the uncleanness or even the inhumanity of non-Jews. Indeed, it has often been noted that the Puritans saw themselves as the true chosen people of the Bible. In the words of Samuel Wakeman, a prominentseventeenth-century Puritan preacher: “Jerusalem was, New England is; they were, you are God’s own, God’s covenant people; put but New England’s name instead of Jerusalem.”[19] “They had left Europe which was their ‘Egypt,’ their place of enslavement, and had gone out into the wilderness on a messianic journey, to found the New Jerusalem.”[20]

Whereas Puritanism as a group evolutionary strategy crumbled when the Puritans lost control of Massachusetts, Diaspora Jews were able to maintain their group integrity even without control over a specific territory for well over 2,000 years. This attests to the greater ethnocentrism of Jews. But, although relatively less ethnocentric, the Puritans were certainly not lacking in moralistic aggression toward members of their ingroup, even when the boundaries of the ingroup were expanded to include all of America, or indeed all of humanity. And while the Puritans were easily swayed by moral critiques of white America, because of their stronger sense of ingroup identity, Jews have been remarkably resistant to moralistic critiques of Judaism.[21]

With the rise of the Jewish intellectual and political movements described in The Culture of Critique, the descendants of the Puritans readily joined the chorus of moral condemnation of America.

The lesson here is that in large part the problem confronting whites stems from the psychology of moralistic self-punishment exemplified at the extreme by the Puritans and their intellectual descendants, but also apparent in a great many other whites. As I have noted elsewhere:

Once Europeans were convinced that their own people were morally bankrupt, any and all means of punishment should be used against their own people. Rather than see other Europeans as part of an encompassing ethnic and tribal community, fellow Europeans were seen as morally blameworthy and the appropriate target of altruistic punishment. For Westerners, morality is individualistic—violations of communal norms . . . are punished by altruistic aggression. . . .

The best strategy for a collectivist group like the Jews for destroying Europeans therefore is to convince the Europeans of their own moral bankruptcy. A major theme of [The Culture of Critique] is that this is exactly what Jewish intellectual movements have done. They have presented Judaism as morally superior to European civilization and European civilization as morally bankrupt and the proper target of altruistic punishment. The consequence is that once Europeans are convinced of their own moral depravity, they will destroy their own people in a fit of altruistic punishment. The general dismantling of the culture of the West and eventually its demise as anything resembling an ethnic entity will occur as a result of a moral onslaught triggering a paroxysm of altruistic punishment. Thus the intense effort among Jewish intellectuals to continue the ideology of the moral superiority of Judaism and its role as undeserving historical victim while at the same time continuing the onslaught on the moral legitimacy of the West. [22]

The Puritan legacy in American culture is indeed pernicious, especially since the bar of morally correct behavior has been continually raised to the point that any white group identification has been pathologized. As someone with considerable experience in the academic world, I can attest to feeling like a wayward heretic back in seventeenth-century Massachusetts when confronted, as I often am, by academic thought police. It’s the moral fervor of these people that stands out. The academic world has become a Puritan congregation of stifling thought control, enforced by moralistic condemnations that aseventeenth-century Puritan minister could scarcely surpass. In my experience, this thought control is far worse in the East coast colleges and universities founded by the Puritans than elsewhere in academia—a fitting reminder of the continuing influence of Puritanism in American life.

Given this state of affairs, what sorts of therapy might one suggest? To an evolutionary psychologist, this moralistic aggression seems obviously adaptive for maintaining the boundaries and policing the behavior of a close-knit group. The psychology of moralistic aggression against deviating Jews (often termed “self-hating Jews”) has doubtless served Jews quite well over the centuries. Similarly, groups of Angles, Jutes, and their Puritan descendants doubtlessly benefited greatly from moralistic aggression because of its effectiveness in enforcing group norms and punishing cheaters and defectors.

There is nothing inherently wrong with moralistic aggression. The key is to convince whites to alter their moralistic aggression in a more adaptive direction in light of Darwinism. After all, the object of moralistic aggression is quite malleable. Ethnonationalist Jews in Israel use their moral fervor to rationalize the dispossession and debasement of the Palestinians, but many of the same American Jews who fervently support Jewish ethnonationalism in Israel feel a strong sense of moralistic outrage at vestiges of white identity in the United States.

A proper Darwinian sense of moralistic aggression would be directed at those of all ethnic backgrounds who have engineered or are maintaining the cultural controls that are presently dispossessing whites of their historic homelands. The moral basis of this proposal is quite clear:

(1) There are genetic differences between peoples, thus different peoples have legitimate conflicts of interest.[23]

(2) Ethnocentrism has deep psychological roots that cause us to feel greater attraction and trust for those who are genetically similar.[24]

(3) As Frank Salter notes, ethnically homogeneous societies bound by ties of kinship and culture are more likely to be open to redistributive policies such as social welfare.[25]

(4) Ethnic homogeneity is associated with greater social trust and political participation.[26]

(5) Ethnic homogeneity may well be a precondition of political systems characterized by democracy and rule of law.[27]

The problem with the Transcendentalists is that they came along before their intuitions could be examined in the cold light of modern evolutionary science. Lacking any firm foundation in science, they embraced a moral universalism that is ultimately ruinous to people like themselves. And because it is so contrary to our evolved inclinations, their moral universalism needs constant buttressing with all the power of the state—much as the rigorous rules of the Puritans of old required constant surveillance by the authorities.

Of course, the Transcendentalists would have rejected such a “positivist” analysis. Indeed, one might note that modern psychology is on the side of the Puritans in the sense that explicitly held ideologies are able to exert control over the more ancient parts of the brain, including those responsible for ethnocentrism.[28] The Transcendentalist belief that the mind is creative and does not merely respond to external facts is quite accurate in light of modern psychological research. In modern terms, the Transcendentalists were essentially arguing that whatever “the animal wants of man” (to quote Emerson), humans are able to imagine an ideal world and exert effective psychological control over their ethnocentrism. They are even able to suppress desires for territory and descendants that permeate human history and formed an important part of the ideology of the Old Testament—a book that certainly had a huge influence on the original Puritan vision of the New Jerusalem.

Like the Puritans, the Transcendentalists would have doubtlessly acknowledged that some people have difficulty controlling these tendencies. But this is not really a problem, because these people can be forced. The New Jerusalem can become a reality if people are willing to use the state to enforce group norms of thought and behavior. Indeed, there are increasingly strong controls on thought crimes against the multicultural New Jerusalem throughout the West.

The main difference between the Puritan New Jerusalem and the present multicultural one is that the latter will lead to the demise of the very white people who are the mainstays of the current multicultural Zeitgeist. Unlike the Puritan New Jerusalem, the multicultural New Jerusalem will not be controlled by people like themselves, who in the long run will be a tiny, relatively powerless minority.

The ultimate irony is that without altruistic whites willing to be morally outraged by violations of multicultural ideals, the multicultural New Jerusalem is likely to revert to a Darwinian struggle for survival among the remnants. But the high-minded descendants of the Puritans won’t be around to witness it.

Notes

[3] Kevin MacDonald, Separation and Its Discontents: Toward an Evolutionary Theory of Anti-Semitism (Bloomington, Ind.: Firstbooks, 2004), Chapter 5.

[4] Kevin MacDonald, The Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth-Century Intellectual and Political Movements (Bloomington, Ind.: Firstbooks, 2002).

[5] David Sloan Wilson, Darwin’s Cathedral (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002); Kevin MacDonald, (2002). “Diaspora Peoples,” Preface to the First Paperback Edition of A People That Shall Dwell Alone: Judaism as a Group Evolutionary Strategy (Lincoln, Nebr.: iUniverse, 2002).

[6] David H. Fischer, Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 202.

[7] Albion’s Seed, 189.

[8] See Darwin’s Cathedral.

[9] Louis T. Merrill, “The Puritan Policeman,” American Sociological Review 10 (1945): 766–76, p. 766.

[10] Kevin Phillips, The Cousins’ Wars: Politics, Civil Warfare, and the Triumph of Anglo-America (New York: Basic Books, 1999).

[11] Ibid., 26.

[12] Ibid., 27.

[13] Kevin MacDonald, “What Makes Western Civilization Unique?” in Cultural Insurrections: Essays on Western Civilization, Jewish Influence, and Anti-Semitism (Atlanta: The Occidental Press, 2007).

[14] Albion’s Seed, 357.

[15] Ernst Fehr and Simon Gächter, “Altruistic Punishment in Humans,” Nature 412 (2002): 137-40.

[16] See my discussion in “Diaspora Peoples.”

[17] The Cousins’ Wars, 477.

[18] Ibid., 556.

[19] A. Hertzberg, The Jews in America: Four Centuries of an Uneasy Encounter (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 20–21.

[20] Ibid., 20.

[21] See Kevin MacDonald, “The Israel Lobby: A Case Study in Jewish Influence,” The Occidental Quarterly 7 (Fall 2007): 33–58.

[22] Preface to the paperback edition of The Culture of Critique.

[23] Frank K. Salter, On Genetic Interests: Family, Ethnicity, and Humanity in an Age of Mass Migration (New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction, 2006).

[24] J. Philippe Rushton, “Ethnic Nationalism, Evolutionary Psychology, and Genetic Similarity Theory,” Nations and Nationalism 11 (2005): 489–507.

[25] Frank K. Salter, Welfare, Ethnicity and Altruism: New Data and Evolutionary Theory (London: Routledge, 2005).

[26] Robert Putnam, “E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the Twenty-first Century,” The 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture, Scandinavian Journal of Political Studies 30 (2007): 137–74.

[27] Jerry Z. Muller, “Us and Them: The Enduring Power of Ethnic Nationalism,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2008.

[28] Kevin MacDonald, “Psychology and White Ethnocentrism,” The Occidental Quarterly 6 (Winter, 2006–2007): 7–46.

Source: TOQ, vol. 8, no. 2 (Summer 2008).

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2012/06/american-transcendentalism/

00:05 Publié dans Livre, Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : livre, philosophie, transcendentalisme américain, transcendentalisme, etats-unis, kevin macdonald |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Viol de masse des Françaises en 1945

Viol de masse des Françaises en 1945 (1 + 2)

00:05 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, deuxième guerre mondiale, seconde guerre mondiale, années 40, crime de guerre |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 07 juillet 2012

The Underman as Cultural Icon

The Underman as Cultural Icon:

The Saga of “Blanket Man”

By Kerry Bolton

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

“Blanket Man,” known in a previous life as Bernard (Ben) Hana, was a filth ridden alcoholic, given to drinking methylated spirits attired in nothing other than a blanket and a loin cloth. He shouted or mumbled abuse at passers-by, as he squatted on the streets of Wellington with others of his ilk. He seemed harmless enough, and this writer has nothing personal against him or the way he chose to lead his life.

What I do find of socio-cultural interest is the manner by which others have turned him into a cultural icon. Such elevation to the presently esteemed status of Anti-Hero says something about the mentality of those who have revived the “Cult of the Noble Savage” that became the rage of effete upper class French society prior to the Revolution. It is a symptom of what Lothrop Stoddard called “the menace of the underman” and “the revolt against civilization.”[1]

Mr. Hana has a Facebook page [2] established by his admirers. There one can learn the fundamentals of his life; a hagiography, one might say. He was born February 8, 1957 and died as the result of his celebrated lifestyle choice on January 15, 2012. He was a “homeless man who wandered the inner city streets of Wellington, New Zealand. Ben was a local fixture and something of a celebrity and was typically on the footpath in the precincts of Courtenay Place which has 24-hour activity.”[2]

When the scribe of Saint Bernard alludes to Courtenay Place’s “24-hour activity,” what this means is that the nightlife brings out lowlifes who engage in drinking, vomiting, excreting in the doorways of shops, and other expressions of societal rebellion.

But what makes Saint Bernard especially esteemed by the champions of the generic Underman is that he was a Maori, complete with matted, filthy, dreadlocked hair, and perhaps the epitome of what liberals, nihilists, and anarchists see as the living vestige of the Maori as he was, prior to European colonization: the “noble savage,” existing in the midst of a modern Western city.

Saint Bernard, despite sizzling his brain with alcohol and marijuana, was no fool, and on the few occasions the City Council attempted to do something about his plight, he had a ready answer for the Courts, exploiting the deference New Zealand society is obliged to show for all things “Maori,” whether real or contrived:

Ben was a self-proclaimed devotee of the Māori sun god Tama-nui-te-rā, and claimed that he should wear as few items of clothing as possible, as an act of religious observance. As a result, he was also tempted from time to time to remove all his clothing, which resulted in the consequent attendance of police officers.[3]

Another blogsite devoted to “Brother,” as he called himself, euologizes his contempt for authority, including his squatting with others of like state, at Wellington’s Cenotaph near Parliament Buildings.[4] On this blogsite one can read comments by, for the most part, admiring youths, aptly expressed in pidgin English, who were in such awe that they could only admire Saint Bernard from afar, as if a Christ-like figure too divine to be approachable, but an individual around which myths and legends can be spun:

- “When he i [sic] first saw blanket man he gave me a big as nod [sic] and he has a smile that makes you feel warm inside.”[5]

- From someone who wants to follow the way, the truth, and the life: “Inspiring Shit When i`m A Bigg Girll ii Wanna Bee Justt Like Him He`sz My idol.”[6]

- “mayn this dude is fucking awesome,, gu cunt. i always go to wellie and see him and he always smiles and nods (and mumbles haha) Hez a legend!”[7]

Such is the “evolution” of New Zealand “English” under several decades of liberal education, where grammar and spelling are not corrected by teachers lest the “creativity” of the child is ruined and s/he is left with a feeling of having failed.

However, Saint Bernard became an icon to more than just ill-educated youngsters. Many of the artistic, intellectual and scribbling classes see him as “a carefree spirit,” rather than an individual who became unbalanced after killing his best friend as the result of drunk driving and died through alcoholism. Marcelina Mastalerz in an interview with “Brother” relates her first impressions of his countenance:

He has become an iconic figure of Wellington’s Cuba Mall and Courtenay Place. Wrapped in a purple blanket, nearly naked, with his long dreads and carefree spirit, to many he is an annoying homeless man who simply won’t go away and who is destroying the beautiful, clean image of our city.[8]

At least this was my opinion of him when I first arrived to Wellington. I would see him, make a sour face and above all avoid eye contact as I quickly crossed the street. After all, his lifestyle and that of mine seemed to illustrate two contrasting worlds, which neither of us would ever understand.

But I started to wonder, who is this ever-present figure, who has no shame in living a lifestyle that society finds unacceptable and degenerating? Surely he must be either an alcoholic, drug addict, insane or all of the above, right?

No. “Brother,” what he likes to call himself, is neither an alcoholic[9] nor an unhappy man. He likes his lifestyle, and above all the freedom, which it gives him.[10]

Ms. Mastalerz was surely blinded by the Light, not to have perceived Saint Bernard as an alcoholic, if not a drug addict. What she saw was a Tolstoyan visage of a man who had succeeded in throwing off all the encumbrances of Civilization, and returned to the “state of Nature” that is heralded by effete intellectuals and bourgeoisie who could not last a day in such a state, but who envy those who seem “happy” to live in filth, rationalized as living an “alternative lifestyle,” or as Ms. Mastalerz and her type insist, living “carefree” and in “freedom.” It is what Lothrop Stoddard called “the lure of the primitive.”[11]

In the course of the interview Saint Bernard relates the gospel of the Underman quite articulately, and one readily sees why he is so irresistible to those who feel the burden of Civilization.

M: I saw the documentary Te Whanau o Aotearoa — Caretakers of the Land. In it you set to establish a “village of peace”– Aotearoa. How is that plan going?

B: It’s getting better. We established a political party “Te Whanau o Our Tea Roa.” There’s one million of us.[12] We live love, peace, harmony, equality at the top irrespective of age or gender.

M: If you had the power to do anything, what would you do?

B: I don’t want power. Power belongs to the people.[13]

Saint Bernard, beneath the filthy façade, worn like a halo, articulated the very ideology that is upheld by the multitude of purveyors of Western decline, from the denizens of the streets to Green Party Members of Parliament, the Secretary General of the United Nations Organization, or the President of the United States: “love, peace, harmony, equality at the top irrespective of age or gender,” the present-day catch cries of Western decay; the contemporary counterpart to “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.”

It is no wonder that Saint Bernard became such an admired figure: This is the Age of the Anti-Hero. In bygone days, our heroes were great soldiers and explorers. Today, a hero can be a filthy drunk who lived, cussed, smoked, and crapped on the city streets. A figure who would be one of a multitude in Calcutta; a figure who will perhaps one day also be one of a multitude in all the cities of a bygone Western Civilization: the Fellaheen.

Another scribe for Saint Bernard, Nyree Barrett, provided a class conflict analysis of “Brother”:

Hana pervades the experience of Wellington, whether we like it or not, he is one of the most visual men in the city and because of this he carries a certain amount of celebrity status. He is the protagonist of Abi King-Jones and Errol Wright’s documentary Te Whanau o Aotearoa, the subject of a Wikipedia site, the inspiration for photographic assignments and poetry (albeit bad poetry), and a “character” to be dressed up as. During the recent rugby sevens tournament I saw a group of young men wearing fake dreads and versions of Hana’s distinct purple blanket.

He is imitated, yet when he discusses his many political ideas through his movement Te Whanau o Aotearoa, they are deemed unimportant. This quasi-political party seeks a reclamation of Aotearoa, from its current state as a bureaucratic colony to an egalitarian and racially non-exclusive land. The alienation and inequality in New Zealand is, for Hana, only going to be solved through a complete upheaval of the current system. This sounds an impossibility in a society so entrenched in hierarchy and class. Despite this, Hana’s ideas do deserve to be heard without his homeless status stifling our reception of them.

If the homeless and mainstream society are ever going to be able to live in one space in harmony, as Hana suggests we do in his ambitious vision of Aotearoa, we must first question and change the mainstream perception of life on the streets.[14]

Here again, Saint Bernard is perceived as a great philosopher and political leader, rather than as a wretch who squatted in filth. He is the New Zealand liberal’s version of the most famous “blanket man” of all: Gandhi. He is extolled as the leader of a “political movement,” which seems never to have amounted to to more than a half-dozen other homeless pot smokers who squatted about him within the central business district.

The latest eulogy to Saint Bernard is a play which we are told will further “immortalize” him. “The Road That Wasn’t There,” to be performed at the world fringe festival at Edinburgh, Scotland, was “inspired” by Hana. Playwright Ralph McCubbin Howell, now resident in Britain, wanted to write something about New Zealand “while taking inspiration from folktales.” “Who better to draw on than a man who became a legend within his own lifetime?”[15]

The play is aimed at children, using puppets, and Hana has been made into a puppet of what is — presumably unintentionally — monstrous visage. Other tributes include a song created in 2012 in tribute to Hana, recorded and released by ZM Radio;[16] and a 2007 Victoria University presentation on Hana by sociology lecturer Mike Lloyd and Doctoral student Bronwyn McGovern.

When Hana died of alcohol poisoning in 2012, a makeshift shrine was created at Courtenay Place, where messages were written on the walls of the ANZ Bank building, and flowers, candles, food and other items were left in tribute. Cecilia Wade-Brown, the Green Party’s Mayor of Wellington, were among those who paid tribute to Hana.

The local Anarchists — a melange of pot-smoking street people and mentally aberrant, histrionic bourgeoisie — quite naturally proclaimed Hana as one of their own and produced a signed, limited edition run of prints depicting the frail, doddering “Brother” as a heroic, strident revolutionary. To the Anarchists, “Blanket Man led quite and [sic] extraordinary life and will be missed by many Wellingtonians and New Zealanders alike following his recent death.”[17]

Where once bards wrote of Knights they now write of Blanket Man. He is an archetype of civilization’s decay, and as such is instinctively embraced by those, whether journalists, lecturers, street kids, or artists, high and low, who feel that civilization is an imposition. I saw the future visage of the Fellaheen West, and it squatted in filth on the streets of Wellington.

Words

1. L Stoddard, The Revolt Against Civilization: The Menace of the Underman (London: Chapman & Hall, 1922), republished 2012 by Wermod & Wermod.

2. “R.I.P. Blanket Man,” “About,” http://www.facebook.com/pages/RIP-BLANKET-MAN/273891829339723?sk=info [2]

3. Ibid.

4. “Blanket Man,” http://www.bebo.com/BlogView.jsp?MemberId=3895594292&BlogId=3895641359 [6]

5. Dr. Stevo, Ibid.

6. Nirvana, ibid.

7. Minta, ibid.

8. Wellington has long since stopped being “beautiful’ or “clean.” I have to question the aesthetic sensibilities of Ms. Mastalerz.

9. Apparently drinking methylated spirits is not to be regarded as a sign of alcoholism.

10. Marcelina Mastalerz, “A Different Way of Life: Interview with ‘Brother’ (a.k.a ‘Blanket Man’),” http://www.bebo.com/BlogView.jsp?MemberId=3895594292&BlogId=3895641359&PageNbr=2 [6]

11. L. Stoddard, chapter IV.

12. Probably an exaggeration.

13. Marcelina Mastalerz.

14. Nyree Barrett, “Perceiving homelessness in Wellington,” http://www.bebo.com/BlogView.jsp?MemberId=3895594292&BlogId=3895641359&PageNbr=2 [6]

15. Sophie Speer, “Myth of Blanket Man takes time trip at coveted Fringe,” The Dominion Post, Wellington, June 26, 2012, http://www.stuff.co.nz/dominion-post/culture/performance/7172069/Wellingtons-Blanket-Man-immortalised-in-play [7]

17. Wellington Craftivism Collective, http://wellingtoncraftivism.blogspot.co.nz/2012/01/blanket-man-limited-edition-prints.html [8]

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2012/06/the-underman-as-cultural-icon-the-saga-of-blanket-man/

00:05 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : kerry bolton, blanket man, ben hana, nouvelle zélande, philosophie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Fabrice LUCHINI à propos de Louis-Ferdinand CÉLINE

Fabrice LUCHINI

à propos de Louis-Ferdinand CÉLINE

00:05 Publié dans Entretiens, Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : littérature, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature française, céline, fabrice luchini |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 06 juillet 2012

Lettre sur l’identité à mes amis souverainistes, par Dominique Venner

Lettre sur l’identité à mes amis souverainistes,

Ex: http://fr.novopress.info/

Quand on appartient à une nation associée à Saint Louis, Philippe le Bel, Richelieu, Louis XIV ou Napoléon, un pays qui, à la fin du XVIIe siècle, était appelé « la grande nation » (la plus peuplée et la plus redoutable), il est cruel d’encaisser les reculs historiques répétés depuis les lendemains de Waterloo, 1870, 1940 et encore 1962, fin ignominieuse de la souveraineté française en Algérie. Une certaine fierté souffre nécessairement.

Dès les années 1930, beaucoup d’esprits français parmi les plus audacieux avaient imaginé trouver dans une Europe à venir en entente avec l’Allemagne, un substitut à cet affaiblissement constant de la France. Après la catastrophe que fut la Seconde Guerre mondiale (qui amplifiait celle de 14-18), naquit un projet légitime en soi. Il fallait interdire à tout jamais une nouvelle saignée mortelle entre Français et Allemands. L’idée était de lier ensemble les deux grands peuples frères de l’ancien Empire carolingien. D’abord par une association économique (la Communauté Européenne du Charbon et de l’Acier), puis par une association politique. Le général de Gaulle voulut concrétiser ce projet par le Traité de l’Elysée (22 janvier 1963), que les Etats-Unis, dans leur hostilité, firent capoter en exerçant des pressions sur la République fédérale allemande.

Ensuite, on est entré dans les dérives technocratiques et mondialistes qui ont conduit à l’usine à gaz appelée “Union européenne”. En pratique, celle-ci est la négation absolue de son appellation. La pseudo “Union européenne” est devenue le pire obstacle à une véritable entente politique européenne respectueuse des particularités des peuples de l’ancien Empire carolingien. L’Europe, il faut le rappeler, c’est d’abord une unité de civilisation multimillénaire depuis Homère, mais c’est aussi un espace potentiel de puissance et une espérance pour un avenir qui reste à édifier.

Pourquoi une espérance de puissance ? Parce qu’aucune des nations européennes d’aujourd’hui, ni la France, ni l’Allemagne, ni l’Italie, malgré des apparences bravaches, ne sont plus des États souverains.

Il y a trois attributs principaux de la souveraineté :

1er attribut : la capacité de faire la guerre et de conclure la paix. Les USA, la Russie, Israël ou la Chine le peuvent. Pas la France. C’est fini pour elle depuis la fin de la guerre d’Algérie (1962), en dépit des efforts du général de Gaulle et de la force de frappe qui ne sera jamais utilisée par la France de son propre chef (sauf si les Etats-Unis ont disparu, ce qui est peu prévisible). Autre façon de poser la question : pour qui donc meurent les soldats français tués en Afghanistan ? Certainement pas pour la France qui n’a rien à faire là-bas, mais pour les Etats-Unis. Nous sommes les supplétifs des USA. Comme l’Allemagne et l’Italie, la France n’est qu’un État vassal de la grande puissance suzeraine atlantique. Il vaut mieux le savoir pour retrouver notre fierté autrement.

2ème attribut de la souveraineté : la maîtrise du territoire et de la population. Pouvoir distinguer entre les vrais nationaux et les autres… On connaît la réalité : c’est l’État français qui, par sa politique, ses lois, ses tribunaux, a organisé le « grand remplacement » des populations, nous imposant la préférence immigrée et islamique avec 8 millions d’Arabo-musulmans (en attendant les autres) porteurs d’une autre histoire, d’une autre civilisation et d’un autre avenir (la charia).

3ème attribut de la souveraineté : la monnaie. On sait ce qu’il en est.

Conclusion déchirante : la France, comme État, n’est plus souveraine et n’a plus de destin propre. C’est la conséquence des catastrophes du siècle de 1914 (le XXe siècle) et du grand recul de toute l’Europe et des Européens.

Mais il y a un « mais » : si la France n’existe plus comme État souverain, le peuple français et la nation existent encore, malgré tous les efforts destinés à les dissoudre en individus déracinés ! C’est le grand paradoxe déstabilisateur pour un esprit français. On nous a toujours appris à confondre l’identité et la souveraineté en enseignant que la nation est une création de l’État, ce qui, pour les Français, est historiquement faux.

C’est pour moi un très ancien sujet de réflexion que j’avais résumé naguère dans une tribune libre publiée dans Le Figaro du 1er février 1999 sous le titre : « La souveraineté n’est pas l’identité ». Je le mettrai en ligne un jour prochain à titre documentaire.

Non, la souveraineté de l’État ne se confond pas avec l’identité nationale. En France, de par sa tradition universaliste et centraliste, l’Etat fut depuis plusieurs siècles l’ennemi de la nation charnelle et de ses communautés constitutives. L’État a toujours été l’acteur acharné du déracinement des Français et de leur transformation en Hexagonaux interchangeables. Il a toujours été l’acteur des ruptures dans la tradition nationale. Voyez la fête du 14 juillet : elle célèbre une répugnante émeute et non un souvenir grandiose d’unité. Voyez le ridicule emblème de la République française : une Marianne de plâtre coiffée d’un bonnet révolutionnaire. Voyez les affreux logos qui ont été imposés pour remplacer les armoiries des régions traditionnelles. Souvenez-vous qu’en 1962, l’État a utilisé toute sa force contre les Français d’Algérie abandonnés à leur malheur. De même, aujourd’hui, il n’est pas difficile de voir que l’État pratique la préférence immigrée (constructions de mosquées, légalisation de la viande hallal) au détriment des indigènes.

Il n’y a rien de nouveau dans cette hargne de l’État contre la nation vivante. La République jacobine n’a fait que suivre l’exemple des Bourbons, ce que Tocqueville a bien montré dans L’Ancien Régime et la Révolution avant Taine et d’autres historiens. Nos manuels scolaires nous ont inculqué une admiration béate pour la façon dont les Bourbons ont écrasé la « féodalité », c’est-à-dire la noblesse et les communautés qu’elle représentait. Politique vraiment géniale ! En étranglant la noblesse et les communautés enracinées, cette dynastie détruisait le fondement de l’ancienne monarchie. Ainsi, à la fin du XVIIIe siècle, la Révolution individualiste (droits de l’homme) triomphait en France alors qu’elle échouait partout ailleurs en Europe grâce à une féodalité et à des communautés restées vigoureuses. Relisez ce qu’en dit Renan dans sa Réforme intellectuelle et morale de la France (disponible en poche et sur Kindle). La réalité, c’est qu’en France l’État n’est pas le défenseur de la nation. C’est une machine de pouvoir qui a sa logique propre, passant volontiers au service des ennemis de la nation et devenant l’un des principaux agents de déconstruction identitaire.

[cc] Novopress.info, 2012, Dépêches libres de copie et diffusion sous réserve de mention de la source d'origine [http://fr.novopress.info/]

00:05 Publié dans Nouvelle Droite | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : souveraineté, souverainisme, identité, dominique venner, europe, européisme, nouvelle droite, mouvement identitaire |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 05 juillet 2012

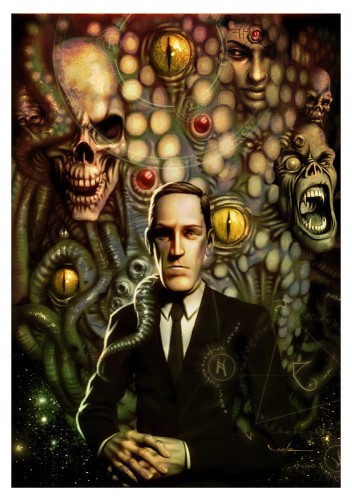

Lovecraft und die Inszenierung der großen Niederlage

|

|

|

|

Geschrieben von: Dietrich Müller

|

|

Ex: http://www.blauenarzisse.de/

|

|

Was für einen Sinn soll es haben, sich mit diesem Mann zu beschäftigen? Er hat eine reiche Korrespondenz hinterlassen und eine überschaubare Anzahl an Geschichten, die dem Horrorgenre zugerechnet werden – das nicht ganz zu Unrecht einen zweifelhaften Ruf genießt. Selbst für einen so früh verstorbenen Mann ist seine Biographie schrecklich mager, sie bietet kaum Höhepunkte, praktisch nichts Erzählenswertes. Geboren, geschrieben, gestorben. Lovecraft in drei Worten. Was kann die Beschäftigung mit diesem Mann uns schon geben? Ein Portrait dieses Mannes zu verfassen, scheitert am biographischen Zugriff. Es soll uns auch nur am Rande kümmern, wie er gelebt hat. Aber aus seinen Widersprüchen und seinen Fähigkeiten lässt sich ein Destillat erzeugen, aus dem sich einiges ziehen lässt und gerade dem kritischen Geist Nahrung liefert. Mehr als Fragment kann es freilich nicht sein, das hätte ihm wohl auch gefallen. Kapitulation hat durchaus etwas Verführerisches. Hat man erst einmal alle Hoffnung persönlich negiert, kann man sich bequem am Leben vorbeidrücken. Widerstand ist anstrengend, nervenaufreibend. Wo man sich an den Zeiten und den Menschen offensiv abmühen muss, da geht es an die Nerven, an die Substanz und der Ausgang bleibt immer mehr als ungewiss. Dem vollendeten Pessimisten ist der Eskapismus nahe. Beides trifft auf Lovecraft zu. Es ist eine Situation, welche die Kritiker heutiger Zeiten (und gerade die Konservativen und Reaktionäre) mit ihm teilen: Alles wird schlechter, die Entwicklungen werden zur Lawine, wir werden erdrückt. Fast könnte man neidisch werden auf die Kollaborateure und ihr zufriedenes Unzufriedensein zwischen Konsum und banalen Sorgen. Das Verführerische an der Kapitulation Viele kennen die Verführung, sich in die Schreibstube zurückzuziehen und abzuwarten, bis die Zeit einen dahinrafft. Diese leise Stimme, dass man sich umsonst abplackt und welch’ hoffnungsloser Irrsinn im dauernden Widerstand liegt. Lieber sich nicht mehr kümmern, nicht mehr teilnehmen. So sind wir doch Lovecrafts Kinder, wenn wir diese Verführung und diese Stimme kennen. Allein: Das stellt den Zweifel nicht ab. Den Schrecken über soviel Unwissen und Dummheit. Das – durchaus auch wohlige Erschauern – beim Ausblick auf künftige Katastrophen. Man blickt aus dem Fenster und beschaut die lachend-dummen Gesichter und fragt sich, wie sie aussehen werden, wenn das Unheil zu ihnen kommt. Der Gedanke gefällt und beunruhigt uns, er zieht uns magisch an den Schreibtisch, denn ganz können wir es nicht unterlassen, uns doch mitzuteilen – und sei es auch nur dem Papier. Nicht weil wir Erfolg wünschen oder Ruhm, sondern weil wir den Eselgesichtern einen Vorgeschmack geben wollen auf die bitteren Zeiten, welche sich für uns so klar abzeichnen. Man hat sich zwar versteckt, aber man kann den prophetischen Akt nicht unterlassen, auch weil man das falsche Glück durchschaut, welchem die Kleingeister da huldigen. Sind wir neidisch auf die Gedankenlosen? Halt! Moment! Wir wollten doch kapitulieren, uns nicht mehr einmischen! Uns der Passivität hingeben und alles verneinen. Wegducken und in Ruhe vergehen. Der Widerspruch nagt an uns. Sind wir neidisch? Ein unschöner Gedanke. Vielleicht so unschön wie wir und die anderen? Wir leben also weit weg vom prallen Leben. Die Menschen und ihr Alltag widern uns an. Unbegreiflich das dumme Tun und der Lauf der Zeit. Wir künden davon und werden alt. Auch aus der Ferne kann man das Schauen nicht unterlassen, die Gedanken nicht abstellen – die Qual sich zu äußern, die Frage, ob nicht alles anders sein könnte. Schließlich knüppeln wir die Hoffnung in den Texten tot. Oder versuchen es zumindest. Nicht mehr nur wegen der anderen, viel mehr noch wegen uns selbst. Abfinden wollen wir uns mit dem Ekel und nicht aufbegehren. Die Welt ist uns unbegreiflich, aber wir uns auch. Was soll dieser Unsinn? Das Leben ist und bleibt ein Saustall und es widert uns an. Geht mir aus den Augen! Gehe mir selbst aus den Augen! Ich tue mir selbst furchtbares an, aber wir auch den anderen. Missgunst und Empathie lassen keine Ruhe aufkommen. Auch die Heimat wird Gefängnis. Welch Verführung, welch Verschwendung! Also zehren wir uns auf Wir werden alt im Zeitraffer. Und krank. Wir schämen uns einerseits ob des ausgewichenen Lebens und sind doch voller Vorfreude, wenn die Zeit uns endlich dahinrafft. Wir spucken auf das erbärmliche Geschenk dieses unnötigen Lebens. Nur auf die Haltung kommt es noch an, auf die letzten Meter, bevor man endlich diesem Scheißhaufen mit seinen Amöbenexistenzen entfliehen kann. Ob einfach nur ein schwarzer Vorhang fällt oder neue Welten, neue Schrecken sich auftun, ist uns egal. Nur weg! Haben wir doch geahnt (oder nur gemeint?), dass es den ganzen Wahn nicht wert ist. Welche Verführung, welche Verschwendung! Also zehren wir uns auf: Uns rührt nicht die Frau, die wir nicht hatten, das Kind nicht, welches wir nie wollten, die Nachwelt nicht, welche wir ablehnen wie die Gegenwart. Wir haben ein Beispiel gegeben oder auch nicht. Das soll andere kümmern. Als uns das Sterben schließlich zerfrisst, blicken wir uns noch einmal delirisch um. Sicher war es alles nichts wert. Oder hoffen wir es nur? Das ist jene drohende, zwiespältige Botschaft, welche Lovecraft, sein Leben und seine Schriften haben. Wir leben in diesem Widerspruch. Die „Fülle der Zeit“ (Gasset) wie im 19. Jahrhundert kennen wir nicht und sie kommt auch nicht wieder. In jedem Zweifler steckt auch ein Nihilist, die wegwerfende Geste, die durchaus auch großartig wirken kann. Dieser Widerspruch und diese Verführung machen uns zu Lovecrafts Kindern. Freilich: Man sollte nicht seinem Beispiel folgen. Der quälende Blick vor dem Ende muss furchtbar sein und ist eine Mahnung. Auch die Glücklichen vergehen Aber wenn wir schließlich in seine Texte schauen, wenn wir angenehm erschauern beim Blick in den irrsinnigen Abgrund dieser sirenenhaften Unfassbarkeit, dann spüren wir, wie nahe er uns gewesen ist. Der Ekel über den alltäglichen Menschen in seiner viehischen Zufriedenheit wird uns bestätigt und am Ende kommt das Böse zu allen und bleibt stark in seiner Unfassbarkeit. Auch die Glücklichen vergehen und ihr Sturz ist noch viel tiefer. Das hilft über manch düstere Momente hinweg. Gerade diese missgünstige Ader, diese Lust am Unglück der Anderen befriedigt Lovecraft für uns. Deswegen redet man auch nicht gerne von ihm, vor allem in Deutschland. Aber auch in der internationalen Rezeption verschanzt man sich hinter schönen Worten oder böser Kritik. Lovecraft hat der „Leere eine Farbe“ gegeben Man sieht es nicht gerne, wenn der Menschenhasser und Katastrophenwünscher in jedem von uns bedient wird. Das literarische Establishment meidet seine Schriften und Visionen. Nicht alleine wegen der rassistischen Untertöne, sondern wegen der verführenden Wirkung und dieses unangenehmen Gefühls, beim eignen Widerspruch ertappt worden zu sein. Er hat der „Leere eine Farbe“ gegeben (Camus), während er konsequent gegen sich selbst lebte. Er ist Verführung und Vergewaltigung zugleich. Destruktiv und autoaggressiv. Selbstbezogen und doch voller Empathie. Ein totaler Widerspruch. Aus der Zeit. „I am Providence.” Alles hatte er überwunden und negiert. Und doch den Gedanken nicht unterlassen. Daran schließlich zerbrochen. Durch die Zeit hat er über diese und seine bescheidene Herkunft triumphiert, indem er seine Niederlage inszenierte. Und heute vernehmen wir vielleicht ein leises Echo eines boshaften Lachens, das möglicherweise von ihm stammt. Er war mehr als „nur“ Providence. In unseren aktuellen Thesen-durch-Fakten-Anschlägen haben wir uns ebenfalls mit dem Thema Pessimismus auseinandergesetzt und dazu sechs Thesen formuliert: Pessimismus ist Feigheit! |

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : lettres, littérature, littérature américaine, lettres américaines, lovecraft |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 04 juillet 2012

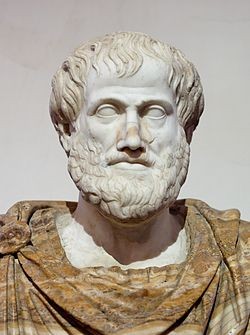

Introduction to Aristotle’s Politics

Introduction to Aristotle’s Politics

Part 1: The Aim & Elements of Politics

Posted By Greg Johnson

Part 1 of 2

Author’s Note:

The following introduction to Aristotle’s Politics focuses on the issues of freedom and popular government. It is a reworking of a more “academic” text penned in 2001.

1. The Necessity of Politics

Aristotle is famous for holding that man is by nature a political animal. But what does this mean? Aristotle explains that,

even when human beings are not in need of each other’s help, they have no less desire to live together, though it is also true that the common advantage draws them into union insofar as noble living is something they each partake of. So this above all is the end, whether for everyone in common or for each singly (Politics 3.6, 1278b19–22).[1]

Here Aristotle contrasts two different needs of the human soul that give rise to different forms of community, one pre-political and the other political.

The first need is material. On this account, men form communities to secure the necessities of life. Because few are capable of fulfilling all their needs alone, material self-interest forces them to co-operate, each developing his particular talents and trading his products with others. The classical example of such a community is the “city of pigs” in the second book of Plato’s Republic.

The second need is spiritual. Even in the absence of material need, human beings will form communities because only through community can man satisfy his spiritual need to live nobly, i.e., to achieve eudaimonia, happiness or well-being, which Aristotle defines as a life of unimpeded virtuous activity.

Aristotle holds that the forms of association which arise from material needs are pre-political. These include the family, the master-slave relationship, the village, the market, and alliances for mutual defense. With the exception of the master-slave relationship, the pre-political realm could be organized on purely libertarian, capitalist principles. Individual rights and private property could allow individuals to associate and disassociate freely by means of persuasion and trade, according to their own determination of their interests.

But in Politics 3.9, Aristotle denies that the realm of material needs, whether organized on libertarian or non-libertarian lines, could ever fully satisfy man’s spiritual need for happiness: “It is not the case . . . that people come together for the sake of life alone, but rather for the sake of living well” (1280a31), and “the political community must be set down as existing for the sake of noble deeds and not merely for living together” (1281a2). Aristotle’s clearest repudiation of any minimalistic form of liberalism is the following passage:

Nor do people come together for the sake of an alliance to prevent themselves from being wronged by anyone, nor again for purposes of mutual exchange and mutual utility. Otherwise the Etruscans and Carthaginians and all those who have treaties with each other would be citizens of one city. . . . [But they are not] concerned about what each other’s character should be, not even with the aim of preventing anyone subject to the agreements from becoming unjust or acquiring a single depraved habit. They are concerned only that they should not do any wrong to each other. But all those who are concerned about a good state of law concentrate their attention on political virtue and vice, from which it is manifest that the city truly and not verbally so called must make virtue its care. (1280a34–b7)

Aristotle does not disdain mutual exchange and mutual protection. But he thinks that the state must do more. It must concern itself with the character of the citizen; it must encourage virtue and discourage vice.

But why does Aristotle think that the pursuit of virtue is political at all, much less the defining characteristic of the political? Why does he reject the liberal principle that whether and how men pursue virtue is an ineluctably private choice? The ultimate anthropological foundation of Aristotelian political science is man’s neoteny. Many animals can fend for themselves as soon as they are born. But man is born radically immature and incapable of living on his own. We need many years of care and education. Nature does not give us the ability to survive, much less flourish. But she gives us the ability to acquire the ability. Skills are acquired abilities to live. Virtue is the acquired ability to live well. The best way to acquire virtue is not through trial and error, but through education, which allows us to benefit from the trials and avoid the errors of others. Fortune permitting, if we act virtuously, we will live well.

Liberals often claim that freedom of choice is a necessary condition of virtue. We can receive no moral credit for a virtue which is not freely chosen but is instead forced upon us. Aristotle, however, holds that force is a necessary condition of virtue. Aristotle may have defined man as the rational animal, but unlike the Sophists of his day he did not think that rational persuasion is sufficient to instill virtue:

. . . if reasoned words were sufficient by themselves to make us decent, they would, to follow a remark of Theognis, justly carry off many and great rewards, and the thing to do would be to provide them. But, as it is, words seem to have the strength to incite and urge on those of the young who are generous and to get a well-bred character and one truly in love with the noble to be possessed by virtue; but they appear incapable of inciting the many toward becoming gentlemen. For the many naturally obey the rule of fear, not of shame, and shun what is base not because it is ugly but because it is punished. Living by passion as they do, they pursue their own pleasures and whatever will bring these pleasures about . . . ; but of the noble and truly pleasant they do not even have the notion, since they have never tasted it. How could reasoned words reform such people? For it is not possible, or nor easy, to replace by reason what has long since become fixed in the character. (Nicomachean Ethics, 10.9, 1179b4–18)

The defect of reason can, however, be corrected by force: “Reason and teaching by no means prevail in everyone’s case; instead, there is need that the hearer’s soul, like earth about to nourish the seed, be worked over in its habits beforehand so as to enjoy and hate in a noble way. . . . Passion, as a general rule, does not seem to yield to reason but to force” (Nicomachean Ethics, 10.9, 1179b23–25). The behavioral substratum of virtue is habit, and habits can be inculcated by force. Aristotle describes law as “reasoned speech that proceeds from prudence and intellect” but yet “has force behind it” (Nicomachean Ethics, 10.9, 1180a18). Therefore, the compulsion of the appropriate laws is a great aid in acquiring virtue.

At this point, however, one might object that Aristotle has established only a case for parental, not political, force in moral education. Aristotle admits that only in Sparta and a few other cities is there public education in morals, while “In most cities these matters are neglected, and each lives as he wishes, giving sacred law, in Cyclops’ fashion, to his wife and children” (Nicomachean Ethics, 10.9, 1180a24–27). Aristotle grants that an education adapted to an individual is better than an education given to a group (Nicomachean Ethics, 10.9, 1180b7). But this is an argument against the collective reception of education, not the collective provision. He then argues that such an education is best left to experts, not parents. Just as parents have professional doctors care for their childrens’ bodies, they should have professional educators care for their souls (Nicomachean Ethics, 10.9, 1180b14–23). But this does not establish that the professionals should be employees of the state.

Two additional arguments for public education are found in Politics 8.1:

[1] Since the whole city has one end, it is manifest that everyone must also have one and the same education and that taking care of this education must be a common matter. It must not be private in the way that it is now, when everyone takes care of their own children privately and teaches them whatever private learning they think best. Of common things, the training must be common. [2] At the same time, no citizen should even think he belongs to himself but instead that each belongs to the city, for each is part of the city. The care of each part, however, naturally looks to the care of the whole, and to this extent praise might be due to the Spartans, for they devote the most serious attention to their children and do so in common. (Politics, 8.1 [5.1], 1337a21–32)

The second argument is both weak and question-begging. Although it may be useful for citizens to “think” that they belong to the city, not themselves, Aristotle offers no reason to think that this is true. Furthermore, the citizens would not think so unless they received precisely the collective education that needs to be established. The first argument, however, is quite strong. If the single, overriding aim of political life is the happiness of the citizens, and if this aim is best attained by public education, then no regime can be legitimate if it fails to provide public education.[2]

Another argument for public moral education can be constructed from the overall argument of the Politics. Since public education is more widely distributed than private education, other things being equal, the populace will become more virtuous on the whole. As we shall see, it is widespread virtue that makes popular government possible. Popular government is, moreover, one of the bulwarks of popular liberty. Compulsory public education in virtue, therefore, is a bulwark of liberty.

2. Politics and Freedom

Aristotle’s emphasis on compulsory moral education puts him in the “positive” libertarian camp. For Aristotle, a free man is not merely any man who lives in a free society. A free man possesses certain traits of character which allow him to govern himself responsibly and attain happiness. These traits are, however, the product of a long process of compulsory tutelage. But such compulsion can be justified only by the production of a free and happy individual, and its scope is therefore limited by this goal. Since Aristotle ultimately accepted the Socratic principle that all men desire happiness, education merely compels us to do what we really want. It frees us from our own ignorance, folly, and irrationality and frees us for our own self-actualization. This may be the rationale for Aristotle’s claim that, “the law’s laying down of what is decent is not oppressive” (Nicomachean Ethics, 10.9, 1180a24). Since Aristotle thinks that freedom from the internal compulsion of the passions is more important than freedom from the external compulsion of force, and that force can quell the passions and establish virtue’s empire over them, Aristotle as much as Rousseau believes that we can be forced to be free.

But throughout the Politics, Aristotle shows that he is concerned to protect “negative” liberty as well. In Politics 2.2–5, Aristotle ingeniously defends private families, private property, and private enterprise from Plato’s communistic proposals in the Republic, thereby preserving the freedom of large spheres of human activity.

Aristotle’s concern with privacy is evident in his criticism of a proposal of Hippodamus of Miletus which would encourage spies and informers (2.8, 1268b22).

Aristotle is concerned to create a regime in which the rich do not enslave the poor and the poor do not plunder the rich (3.10, 1281a13–27).

Second Amendment enthusiasts will be gratified at Aristotle’s emphasis on the importance of a wide distribution of arms in maintaining the freedom of the populace (2.8, 1268a16-24; 3.17, 1288a12–14; 4.3 [6.3], 1289b27–40; 4.13 [6.13], 1297a12–27; 7.11 [4.11], 1330b17–20).

War and empire are great enemies of liberty, so isolationists and peace lovers will be gratified by Aristotle’s critique of warlike regimes and praise of peace. The good life requires peace and leisure. War is not an end in itself, but merely a means to ensure peace (7.14 [4.14], 1334a2–10; 2.9, 1271a41–b9).

The best regime is not oriented outward, toward dominating other peoples, but inward, towards the happiness of its own. The best regime is an earthly analogue of the Prime Mover. It is self-sufficient and turned inward upon itself (7.3 [4.3], 1325a14–31). Granted, Aristotle may not think that negative liberty is the whole of the good life, but it is an important component which needs to be safeguarded.[3]

3. The Elements of Politics and the Mixed Regime

Since the aim of political association is the good life, the best political regime is the one that best delivers the good life. Delivering the good life can be broken down into two components: production and distribution. There are two basic kinds of goods: the goods of the body and the goods of the soul.[4] Both sorts of goods can be produced and distributed privately and publicly, but Aristotle treats the production and distribution of bodily goods as primarily private whereas he treats the production and distribution of spiritual goods as primarily public. The primary goods of the soul are moral and intellectual virtue, which are best produced by public education, and honor, the public recognition of virtue, talent, and service rendered to the city.[5] The principle of distributive justice is defined as proportionate equality: equally worthy people should be equally happy and unequally worthy people should be unequally happy, commensurate with their unequal worth (Nicomachean Ethics, 5.6–7). The best regime, in short, combines happiness and justice.

But how is the best regime to be organized? Aristotle builds his account from at least three sets of elements.