dimanche, 15 juillet 2012

Guillaume Faye on Nietzsche

Guillaume Faye on Nietzsche

Translated by Greg Johnson

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

Translator’s Note:

The following interview of Guillaume Faye is from the Nietzsche Académie [2] blog.

How important is Nietzsche for you?

Reading Nietzsche has been the departure point for all values and ideas I developed later. In 1967, when I was a pupil of the Jesuits in Paris, something incredible happened in philosophy class. In that citadel of Catholicism, the philosophy teacher decided to do a year-long course on Nietzsche! Exeunt Descartes, Kant, Hegel, Marx, and others. The good fathers did not dare say anything, despite the upheaval in the program.

It marked me, believe me. Nietzsche, or the hermeneutics of suspicion. . . . Thus, very young, I distanced myself from the Christian, or rather “Christianomorphic,” view of the world. And of course, at the same time, from egalitarianism and humanism. All the analyses that I developed later were inspired by the insights of Nietzsche. But it was also in my nature.

Later, much later, just recently, I understood the need to complete the principles of Nietzsche with those of Aristotle, the good old Apollonian Greek, a pupil of Plato, whom he respected as well as criticized. There is for me an obvious philosophical affinity between Aristotle and Nietzsche: the refusal of metaphysics and idealism, and, crucially, the challenge to the idea of divinity. Nietzsche’s “God is dead” is the counterpoint to Aristotle’s motionless and unconscious god, which is akin to a mathematical principle governing the universe.

Only Aristotle and Nietzsche, separated by many centuries, denied the presence of a self-conscious god without rejecting the sacred, but the latter is akin to a purely human exaltation based on politics or art.

Nevertheless, Christian theologians have never been bothered by Aristotle, but were very much so by Nietzsche. Why? Because Aristotle was pre-Christian and could not know Revelation. While Nietzsche, by attacking Christianity, knew exactly what he was doing.

Nevertheless, the Christian response to this atheism is irrefutable and deserves a good philosophical debate: faith is a different domain than the reflections of philosophers and remains a mystery. I remember, when I was with the Jesuits, passionate debates between my Nietzschean atheist philosophy teacher and the good fathers (his employers) sly and tolerant, sure of themselves.

What book by Nietzsche would you recommend?

The first one I read was The Gay Science. It was a shock. Then Beyond Good and Evil, where Nietzsche overturns the Manichean moral rules that come from Socrates and Christianity. The Antichrist, it must be said, inspired the whole anti-Christian discourse of the neo-pagan Right, in which I was obviously heavily involved.

But it should be noted that Nietzsche, who was raised Lutheran, had rebelled against Christian morality in its purest form represented by German Protestantism, but he never really understood the religiosity and the faith of traditional Catholics and Orthodox Christians, which is quite unconnected to secularized Christian morality.

Oddly, I was never excited by Thus Spoke Zarathustra. For me, it is a rather confused work, in which Nietzsche tried to be a prophet and a poet but failed. A bit like Voltaire, who believed himself clever in imitating the tragedies of Corneille. Voltaire, an author who, moreover, has spawned ideas quite contrary to this “philosophy of the Enlightenment” that Nietzsche (alone) had pulverized.

Being Nietzschean, what does this mean?

Nietzsche would not have liked this kind of question, for he did not want disciples, though . . . (his character, very complex, was not devoid of vanity and frustration, just like you and me). Ask instead: What does it mean to follow Nietzschean principles?

This means breaking with Socratic, Stoic, and Christian principles and modern human egalitarianism, anthropocentrism, universal compassion, and universalist utopian harmony. It means accepting the possible reversal of all values (Umwertung) to the detriment of humanistic ethics. The whole philosophy of Nietzsche is based on the logic of life: selection of the fittest, recognition of vital power (conservation of bloodlines at all costs) as the supreme value, abolition of dogmatic standards, the quest for historical grandeur, thinking of politics as aesthetics, radical inegalitarianism, etc.

That’s why all the thinkers and philosophers — self-appointed, and handsomely maintained by the system — who proclaim themselves more or less Nietzschean, are impostors. This was well understood by the writer Pierre Chassard who on good authority denounced the “scavengers of Nietzsche.” Indeed, it is very fashionable to be “Nietzschean.” Very curious on the part of publicists whose ideology — political correctness and right-thinking — is absolutely contrary to the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche.

In fact, the pseudo-Nietzscheans have committed a grave philosophical confusion: they held that Nietzsche was a protest against the established order, but they pretended not to understand that it was their own order: egalitarianism based on a secularized interpretation of Christianity. “Christianomorphic” on the inside and outside. But they believed (or pretended to believe) that Nietzsche was a sort of anarchist, while advocating a ruthless new order. Nietzsche was not, like his scavengers, a rebel in slippers, a phony rebel, but a revolutionary visionary.

Is Nietzsche on the Right or Left?

Fools and shallow thinkers (especially on the Right) have always claimed that the notions of Left and Right made no sense. What a sinister error. Although the practical positions of the Left and Right may vary, the values of Right and Left do exist. Nietzscheanism is obviously on the Right. The socialist mentality, the morality of the herd, made Nietzsche vomit. But that does not mean that thepeople of the extreme Right are Nietzscheans, far from it. For example, they are generally anti-Jewish, a position that Nietzsche castigated and considered stupid in many of his writings, and in his correspondence he singled out anti-Semitic admirers who completely misunderstood him.

Nietzscheanism, obviously, is on the Right, and the Left, always in a position of intellectual prostitution, attempted to neutralize Nietzsche because it could not censor him. To be brief, I would say that an honest interpretation of Nietzsche places him on the side of the revolutionary Right in Europe, using the concept of the Right for lack of anything better (like any word, it describes things imperfectly).

Nietzsche, like Aristotle (and, indeed, like Plato, Kant, Hegel, and Marx, of course — but not at all Spinoza) deeply integrated politics in his thinking. For example, by a fantastic premonition, he was for a union of European nations, like Kant, but from a very different perspective. Kant the pacifist, universalist, and incorrigible utopian moralist, wanted the European Union as it exists today: a great flabby body without a sovereign head with the Rights of Man as its highest principle. Nietzsche, on the contrary, spoke of Great Politics, a grand design for a united Europe. For the moment, it is the Kantian view that has unfortunately been imposed.

On the other hand, the least we can say is that Nietzsche was not a Pan-German, a German nationalist, but rather a nationalistic — and patriotic — European. This was remarkable for a man who lived in his time, the second part of the 19th century (“This stupid 19th century,” said Léon Daudet), which exacerbated as a fatal poison the shabby petty intra-European nationalism that would result in the terrible fratricidal tragedy of 1914 to 1918, when young Europeans from 18 to 25 years, massacred one another without knowing exactly why. Nietzsche the European wanted anything but such a scenario.

That is why those who instrumentalized Nietzsche (in the 1930s) as an ideologue of Germanism are as wrong as those who, today, present him as a proto-Leftist. Nietzsche was a European patriot, and he put the genius of the German soul in the service of European power whose decline, as a visionary, he already sensed.

What authors do you see as Nietzschean?

Not necessarily those who claim Nietzsche. In reality, there are no actual “Nietzschean” authors. Simply, Nietzsche and others are part of a highly fluid and complex current that could be described as a “rebellion against the accepted principles.” On this point, I agree with the view of the Italian philosopher Giorgio Locchi, who was one of my teachers: Nietzsche inaugurated “superhumanism,” that is to say the surpassing of humanism. I’ll stop there, because I will not repeat what I have developed in some of my books, including Why We Fight and Sex and Perversion. One could say that a large number of authors and filmmakers are “Nietzschean,” but this kind of talk is very superficial.

On the other hand, I believe there is a strong link between the philosophy of Nietzsche and Aristotle, despite the centuries that separate them. To say that Aristotle is Nietzschean is obviously an anachronistic absurdity. But to say that Nietzsche’s philosophy continues Aristotle, the errant student of Plato, is a claim I will hazard. This is why I am both Aristotelian and Nietzschean: Because these two philosophers defend the fundamental idea that the supernatural deity must be examined in substance. Nietzsche looks at divinity with a critical perspective like Aristotle’s.

Most writers who call themselves admirers of Nietzsche are impostors. Paradoxically, I link Darwinism and Nietzsche. Those who actually interpret Nietzsche are accused by ideological manipulators of not being real “philosophers.” Even those who want Nietzsche to say the opposite of what he so inconveniently actually said. We must condemn this appropriation of philosophy by a caste of mandarins who proceed to distort the texts of the philosophers, or even censor them. Aristotle has also been a victim. One can read Nietzsche and other philosophers only through a scholarly grid, inaccessible to the common man. But no. Nietzsche is quite readable by any educated man. But our time can read only through the grid of censorship by omission.

Could you give a definition of the Superman?

Nietzsche intentionally gave a vague definition of the Superman. This is an open-ended yet clear concept. Obviously, the pseudo-Nietzschean intellectuals were quick to blur and empty this concept by making the Superman a sort of airy intellectual: detached, haughty, meditative, quasi-Buddhist—the conceited image they have of themselves. In short, the precise opposite of what Nietzsche intended. I am a partisan not of interpreting writers but of reading them, if possible, with the highest degree of respect.

Nietzsche obviously linked the Superman to the notion of Will to Power (which, too, has been manipulated and distorted). The Superman is the model of the man who fulfills the Will to Power, that is to say, who rises above herd morality (and Nietzsche thought socialism was a herd doctrine) to selflessly impose a new order, with two dimensions, warlike and sovereign, aiming at dominion, endowed with a power project. The interpretation of the Superman as a supreme “sage,” a non-violent, ethereal, proto-Gandhi of sorts is a deconstruction of Nietzsche’s thought in order to neutralize and blur it. The Parisian intelligentsia, whose hallmark is a spirit of falsehood, has a sophisticated but evil genius in distorting the thought of annoying but unavoidable great authors (including Aristotle and Voltaire) but also wrongly appropriating or truncating their thought.

There are two possible definitions of the Superman: the mental and the moral Superman (by evolution and education, surpassing his ancestors) and the biological superman. It’s very difficult to decide, since Nietzsche himself has used this expression as a sort of mytheme, a literary trope, without ever truly conceptualizing it. A sort of premonitory phrase, which was inspired by Darwinian evolutionism.

But your question is very interesting. The key is not having an answer “about Nietzsche,” but to know which path Nietzsche wanted to open over a hundred years ago. Because he was anti-Christian and anti-humanist, Nietzsche did not think that man was a fixed being, but that he is subject to evolution, even self-evolution (that is the sense of the metaphor of the “bridge between the beast and the Superman”).

For my part — but then I differ with Nietzsche, and my opinion does not possess immense value — I interpreted superhumanism as a challenge, for reasons partly biological, to the very notion of a human species. Briefly. This concept of the Superman is certainly much more than Will to Power, one of those mysterious traps Nietzsche set, one of the questions he posed to future humanity: Yes, what is the Superman? The very word makes us dreamy and delirious.

Nietzsche may have had the intuition that the human species, at least some of its higher components (not necessarily “humanity”), could accelerate and direct biological evolution. One thing is certain, that crushes the thoughts of monotheistic, anthropocentric “fixists”: man is not an essence that is beyond evolution. And then, to the concept of Übermensch, never forget to add that ofHerrenvolk . . . prescient. Also, we should not forget Nietzsche’s reflections on the question of race and anthropological inequality.

The capture of Nietzsche’s work by pseudo-scientists and pseudo-philosophical schools (comparable to the capture of the works of Aristotle) is explained by the following simple fact: Nietzsche is too big a fish to be eliminated, but far too subversive not to be censored and distorted.

Your favorite quote from Nietzsche?

“We must now cease all forms of joking around.” This means, presciently, that the values on which Western civilization are based are no longer acceptable. And that survival depends on a reversal or restoration of vital values. And all this assumes the end of festivisme (as coined by Philippe Muray and developed by Robert Steuckers) and a return to serious matters.

Source: http://nietzscheacademie.over-blog.com/article-nietzsche-vu-par-guillaume-faye-106329446.html [3]

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2012/07/guillaume-faye-on-nietzsche/

00:05 Publié dans Nouvelle Droite, Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, nouvelle droite, guillaume faye, nietzsche, surhumanisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 14 juillet 2012

Warrior heritage of Ukrainian Cossacks

Warrior heritage of Ukrainian Cossacks

00:05 Publié dans Militaria, Musique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (2) | Tags : cosaques, russie, ukraine, histoire, militaria, musique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 13 juillet 2012

Akhenaton, Fils du Soleil par Savitri Devi

La vie est un culte:

Akhenaton, Fils du Soleil par Savitri Devi

By Mark Brundsen

Traduit par Arjuna / Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

English original here

Savitri Devi demeure une figure énigmatique dans l’histoire récente. Elle est probablement le mieux connue comme la « prêtresse d’Hitler »,[1] une partisane farouchement impénitente de l’Allemagne nationale-socialiste, et portée au mysticisme. On se rappelle probablement d’elle de cette manière parce que cela nous permet de catégoriser ses idées. Si on se rappelle d’elle un jour, ce sera précisément à cause de l’absence de « mal pur » chez elle, cette étrange qualité qui est attribuée à d’autres figures nationale-socialistes dans le but de les rejeter. Le paradoxe qu’elle incarne, celui d’une nazie déclarée et aimante, est trop incompréhensible pour que certains puissent même l’examiner.

Savitri Devi demeure une figure énigmatique dans l’histoire récente. Elle est probablement le mieux connue comme la « prêtresse d’Hitler »,[1] une partisane farouchement impénitente de l’Allemagne nationale-socialiste, et portée au mysticisme. On se rappelle probablement d’elle de cette manière parce que cela nous permet de catégoriser ses idées. Si on se rappelle d’elle un jour, ce sera précisément à cause de l’absence de « mal pur » chez elle, cette étrange qualité qui est attribuée à d’autres figures nationale-socialistes dans le but de les rejeter. Le paradoxe qu’elle incarne, celui d’une nazie déclarée et aimante, est trop incompréhensible pour que certains puissent même l’examiner.

En conséquence, Savitri Devi reste une voie obligatoire dans une vision historique plus réaliste du national-socialisme ; ses écrits révèlent une vision-du-monde implicite qui est activement combative et dynamique, une possibilité inconcevable pour beaucoup de gens qui acceptent la vision d’après-guerre, ossifiée et monolithique, du national-socialisme. Cela ne veut pas dire que ses idées doivent remplacer les autres visions que nous avons du mouvement, mais qu’elles doivent nous en révéler les multiples dimensions, dont les siennes ne sont qu’une partie. Pour cette raison, Savitri Devi offre des leçons précieuses aux nationaux-socialistes d’aujourd’hui, qui peuvent apprendre à défendre un idéal moins dérivé d’une vision mutilée de l’histoire (et de son opposition polaire), tout comme aux accepteurs passifs de cette orthodoxie du mal, construite par leur crainte de tout schéma complexe.

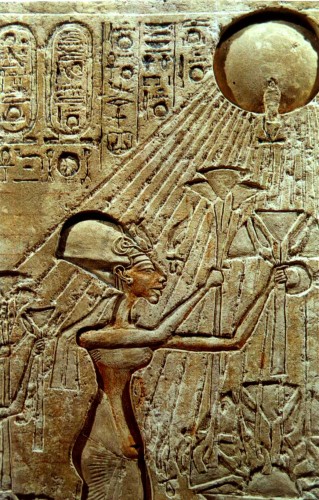

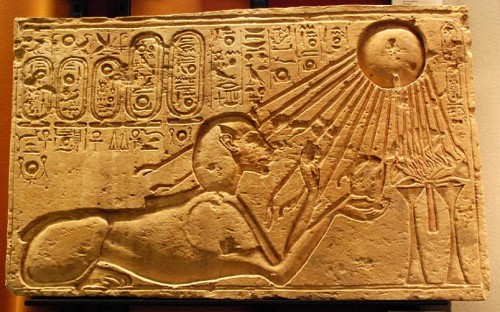

C’est dans cet esprit que je voudrais examiner son livre Akhenaton, Fils du Soleil : la vie et la philosophie d’Akhenaton, Roi d’Egypte,[2] écrit pendant la seconde guerre mondiale, alors que l’auteur demeurait en Inde, loin de la calamité en Europe, regardant anxieusement la tragédie de son mouvement. Le texte est un examen approfondi de la vie d’Akhenaton en tant que Pharaon apostat et des détails de son culte de la puissance solaire, Aton.

Le texte est divisé en trois parties : une description du début de la vie du roi, incluant son ascension et son remplacement de la religion nationale ; une discussion des particularités et des implications de l’atonisme ; et un exposé du déclin conséquent de l’Egypte à cause du refus par Akhenaton de faire des compromis concernant ses croyances, qui se termine par un chapitre examinant les leçons que les gens d’aujourd’hui peuvent tirer de la vie et de la religion d’Akhenaton.

Le chapitre final révèle le but ultime de Savitri Devi, qu’elle expose elle-même, c’est-à-dire présenter pour examen l’œuvre intellectuelle d’un héros oublié : un système de croyance antique, mais étonnamment contemporain, dont elle pensait qu’il avait le potentiel pour éclairer le chemin au-delà de l’impasse de la mentalité moderne, handicapée par la coupure entre science (ou rationalité) et religion, un système à la vision large.

Le style de Savitri Devi révèle sa personnalité ; en lisant Fils du Soleil, on peut voir à l’œuvre une penseuse hautement dévouée et passionnée, qui s’efforce de trouver toutes les informations (employées de manière créative) pour faire avancer sa thèse. Celle-ci peut constituer un choc pour le lecteur contemporain, trop préoccupé par le leurre de l’objectivité en histoire, et n’est pas aidée par le fait qu’à l’époque il n’y avait qu’une fraction des études sur Akhenaton disponibles aujourd’hui.

Savitri Devi utilise sans vergogne son imagination pour spéculer sur les détails de la vie du roi (en particulier sa description de l’éducation d’Akhenaton, de sa haute considération pour sa femme, de la vie dans sa nouvelle capitale Akhetaton, et la facilité avec laquelle Akhenaton comprenait intuitivement des faits que la science moderne a décrits depuis lors). Cela ne donne pas toujours l’impression d’être érudit, malgré son affirmation répétée de la valeur de la rationalité.

Savitri Devi considère comme son devoir de discuter d’Akhenaton comme d’un génie, d’un maître spirituel et intellectuel, et entreprend sa tâche d’une manière active et créative. Pour accepter ce fait, il faut considérer Fils du Soleil comme un exposé des idées de Savitri Devi tout autant que de la vie d’Akhenaton. Si on peut accepter cela, Fils du Soleil est une lecture riche et gratifiante.

La première partie du livre sert surtout à présenter le contexte dans lequel commença la vie d’Akhenaton, et aide aussi le lecteur à se familiariser au style de Savitri Devi. Celle-ci semble enivrée par sa description de l’Egypte impériale ; elle consacre un temps considérable à décrire la richesse et le pouvoir à la disposition de son roi, et la portée de son règne, qui impliqua une influence à la fois économique et religieuse. Le début de la vie d’Akhenaton est scruté de la même manière, et elle admet que les détails en sont déduits de ce que l’on sait de la fin de la vie de l’homme (p. 19). Elle fait cela très longuement, incluant la spéculation sur les origines ou les influences de ce qui devait devenir sa religion.

Quelque temps après que le prince soit devenu Pharaon, et ayant subi un changement religieux intérieur, il érigea un temple consacré au dieu Aton, une déité solaire déjà adorée en Egypte, peut-être synonyme de Râ. Si les murs du temple contiennent des images d’Aton aux cotés d’Amon et d’autres dieux nationaux, un peu plus tard la tolérance du roi disparut et toute l’iconographie religieuse fut enlevée, sauf celle d’Aton. C’est la principale trace historique des réformes d’Akhenaton : les influents prêtres d’Amon furent empêchés de pratiquer officiellement et l’atonisme fut déclaré seule religion légitime. Le problème d’Akhenaton, cependant, était que sa religion panthéiste innovante ne plaisait pas aux profanes, et Savitri Devi se demande même si ses adeptes n’ont pas été motivés simplement par un désir de promotion. La résolution d’Akhenaton impliquait la construction d’une nouvelle capitale pour l’Egypte, à nouveau décrite d’une manière glorieuse et créative.

La seconde partie consiste en un examen de l’atonisme, principalement à travers une lecture attentive des deux hymnes survivants d’Akhenaton (dont de multiples traductions sont fournies en appendice), et contient donc à la fois les idées centrales d’Akhenaton et de Savitri Devi. Dans les hymnes, Akhenaton désigne Aton, le disque du soleil, par divers autres termes. Le terme qui intéresse Savitri Devi est « Shu-qui-est-dans-le-disque », où Shu évoque à la fois la chaleur et la lumière. Elle compare cet usage aux références similaires d’Akhenaton aux grondements du tonnerre et de la foudre, qu’il assimile à Aton. Savitri Devi utilise ces deux indications pour suggérer qu’Akhenaton avait une conception profonde de l’énergie, de la chaleur et de la lumière, les considérant finalement comme équivalentes, un fait qui a été ostensiblement validé par la recherche scientifique.

L’indication de cette compréhension poussa Sir Flinders Petrie, dans son History of Egypt [1899], citée par Savitri Devi (p. 293), à remarquer : « Si c’était une nouvelle religion inventée pour satisfaire nos conceptions scientifiques modernes, nous ne pourrions pas trouver de défaut dans la correction de la vision [d’Akhenaton] de l’énergie du système solaire ». Sir Wallis Budge est cité comme affirmant que Akhenaton ne vénérait qu’un objet matériel, le soleil littéral, mais Savitri Devi rejette cela en citant des exemples où Akhenaton parle du Ka du Soleil, son âme ou son essence. Budge reconnaît aussi que la vision d’Akhenaton est celle d’un Disque créé par lui-même et existant par lui-même, ce qui est une distinction marquée par rapport aux vieux cultes héliopolitains qui incluaient une figure créatrice.

Akhenaton semble avoir suivi cette approche religieuse rationnelle avec cohérence. Son enseignement est entièrement dénué de récits mythologiques, de récits de miracles, et de métaphysique. La thèse de Savitri Devi en concevant la religion du Disque est que Akhenaton voyait et adorait la divinité dans la vie elle-même.

Dans ses hymnes, Akhenaton affirme l’origine terrestre du Nil et compare ses bienfaits à ceux des autres fleuves et de la pluie, rompant avec l’idée habituelle de l’origine divine du Nil, ou de tout ce qui était source d’eau. Akhenaton affirme également sa propre origine terrestre, s’opposant à la pratique acceptée des pharaons prétendant à une naissance divine. Akhenaton conserve ainsi sa connexion divine directe – il s’appelle lui-même Fils de Râ – mais transfère sa conception divine à une conception qui est physique sans ambiguïté.

La probabilité de l’accent porté par la religion sur l’immanence est accrue par l’absence d’idolâtrie. Akhenaton n’adore ni « un dieu… à l’image d’un homme, ni même un pouvoir individuel », mais une « réalité impersonnelle » (p. 141). Cela est aussi cohérent avec une absence de prescriptions morales dans le culte, qui contient seulement la valeur (que Akhenaton applique à lui-même, par un surnom régulier) « vivre-dans-la-vérité » : ce qui compte, c’est de mettre un esprit particulier dans ses actions (p. 193).

Une telle absence n’empêche cependant pas Savitri Devi de suggérer ce que cet esprit peut apprécier, par l’examen des hymnes. Alors que de nombreux commentateurs avaient précédemment souligné l’internationalisme et l’« objection de conscience à la guerre » (Weigall cité dans le texte, p. 150) d’Akhenaton, et son amour de tous les êtres humains, Savitri Devi lit les hymnes d’une manière moins anthropocentrique. Elle affirme que les hymnes expriment « la fraternité de tous les êtres sensibles, humains et non-humains » (p. 150, souligné dans l’original), et que par leur nature même les animaux adoraient le Ka du Disque, effaçant ainsi la séparation entre homme et bête, ou matériel et métaphysique (si fortement affirmée par la pensée juive, grecque et chrétienne). Les plantes sont aussi inclues dans l’hymne, bien que pas comme des agents aussi actifs que les animaux.

La discussion de Savitri Devi culmine dans son affirmation que Akhenaton était opposé à l’anthropocentrisme : l’idée que l’homme est un être unique et privilégié et que la seule valeur de l’environnement est son utilité pour l’homme (p. 161). Ses propres idées sur le sujet sont développées plus complètement dans Impeachment of Man. En proposant une telle vision centrée sur la vie, Savitri Devi précède même l’essai majeur de Aldo Leopold, The Land Ethic (1949), qui est généralement considéré comme l’année zéro pour l’éthique environnementale moderne et l’écologie profonde. Inutile de le dire, notre but en mentionnant cela n’est pas de présenter Savitri Devi comme la mère de ces développements, car le courant intellectuel dominant n’est pas intéressé par ses idées et celles-ci ont donc eu peu d’influence.

Savitri Devi interprète aussi les hymnes d’Akhenaton comme encourageant un nationalisme bienveillant. Si Akhenaton percevait la fraternité de toutes les créatures (unissant l’humanité par le fait de leur relation singulière avec Aton), il pensait aussi que Aton « a mis chaque homme à sa place », ce qui inclut la division en peuples « étranges » (et différents) (p. 158, note). Ici Savitri Devi discute en détail des droits de tous les peuples à l’autodétermination et de sa farouche opposition à l’impérialisme.

Finalement, Savitri Devi spécule sur la vision des femmes par Akhenaton, exprimée par le fait que, contrairement à la coutume, il n’eut qu’une seule femme (bien que cela ait ultérieurement été prouvé comme faux), et par l’inclusion de Nefertiti dans les hymnes, apparemment en tant qu’égale d’Akhenaton. Elle reconnaît, cependant, que nous ne savons pas de quelle manière ou à quel degré la reine comprenait la religion de son époux.

La partie finale du livre se concentre sur les résultats de la vision-du-monde du pharaon. A cause de sa négligence de la politique impériale, condamnée par ses croyances, l’Etat déclina. Dans un grand nombre de territoires conquis, des vassaux loyaux, menacés par des invasions et des soulèvements, appelèrent désespérément à l’aide le pharaon, auquel ils avaient payé un tribut régulier et important. Akhenaton refusa d’intervenir, et répondit à peine à leurs lettres, dont la plupart ont été préservées ; il retarda même pendant des mois une audience avec un messager.

Alors que les autres historiens ont interprété cette apathie comme de l’égoïsme, Savitri Devi accorde la bénéfice du doute à Akhenaton et explique cette inaction par sa croyance en l’autodétermination des tribus et des nations, et voit cette tragique effusion de sang comme la seule issue dans une situation bloquée, la véritable mise à l’épreuve pour les principes du pharaon. Il pouvait soit réprimer les soulèvements dans le sang, ce qui aurait entretenu l’hostilité, soit autoriser un conflit sacrificiel final, ce qui mettrait fin à l’escalade de la violence, celle de l’oppression tout comme celle de la résistance. Cette approche est en opposition avec les impératifs dictés par l’individualisme moderne, qui ne possède aucun mécanisme pour stopper un tel processus.

Inutile de le dire, un tel résultat était un suicide politique, et Savitri Devi continue à spéculer sur ce qui aurait pu se passer si Akhenaton avait tenté de répandre sa religion en utilisant la force, décrivant une expansion mondiale du culte. Cependant, cela aurait été contraire à l’essence même de cette religion, qui est élitiste, reposant sur une intuition profonde de l’essence de l’univers et de l’Etre. Le destin d’Akhenaton, consistant à être oublié et de voir sa religion abolie avec hostilité, était donc pour Savitri Devi « le prix de la perfection ». Savitri Devi conclut son ouvrage en examinant directement la pertinence de cette religion pour les Aryens d’aujourd’hui.

D’après cet exposé, il est clair qu’il y a quelques idées contradictoires dans Fils du Soleil, ce qui devrait nous inciter à considérer Savitri Devi comme une propagandiste du mal à l’esprit partisan. Malheureusement, alors que Savitri Devi dépense une énergie excessive à répéter et à souligner ses thèses (au point que le livre est inutilement long), elle néglige pour la plus grande part certains points contradictoires, qui restent ainsi non résolus dans le texte. Cela ne veut pas dire qu’ils compromettent les buts de Savitri Devi, mais que des occasions de développer ses idées ne sont pas exploitées, très probablement parce qu’elle ne voyait pas nécessairement de contradiction, alors que ses lecteurs contemporains en verront probablement une.

Les contradictions centrales sont, d’une part, celle entre son affirmation de la vision universaliste de la vie et la division des races humaines, et d’autre part sa présentation d’Akhenaton comme le premier individu du monde par opposition à l’appui de Savitri à ses politiques anti-individuelles. Ces difficultés finissent par disparaître si l’on fait quelques distinctions subtiles, qui sont si souvent négligées par les nationalistes tout comme par leurs adversaires aujourd’hui, très probablement à cause d’une interprétation orthodoxe de la seconde guerre mondiale.

Les buts du nationalisme ne coïncident pas nécessairement avec ceux de l’impérialisme, et Savitri Devi fait résolument la distinction entre eux. Le fait que l’humanité soit une fraternité sous le regard d’Aton n’exige pas que toutes les cultures effacent leurs différences ; au contraire, cela les encourage à célébrer leurs différents chemins de vie et de culte.

La révélation de la fraternité universelle ne pousse pas non plus Savitri Devi à adopter une position populiste : elle approuve le refus d’Akhenaton d’édulcorer sa religion pour les masses, qui ne feraient que la pervertir. Les gens d’aujourd’hui pourraient se plaindre d’un « double langage » dans la hiérarchie des droits en Egypte, mais Savitri Devi considère naturellement ces différences comme supérieures à une position totalement égalitaire.

La répugnance d’Akhenaton à se concilier les masses est poétique et pure, mais futile. Cela soulève la question même du règne de l’élite, car si celui-ci est juste mais ne peut jamais être correctement établi, quel est l’intérêt de le théoriser et de le défendre ? La norme politique aujourd’hui est simplement plus populiste, avec l’attente du suffrage universel, qui est lié au concept d’humanité. René Guénon met en garde contre un tel règne lorsqu’il déclare que « l’opinion de la majorité ne peut être que l’expression de l’incompétence ».[3] Mais dès que ces pouvoirs ont été accordés, comment la situation peut-elle être inversée ? Ce problème est éternel, puisqu’il est la question centrale de la politique, et nous ne pouvons pas nous attendre à ce que Savitri Devi le résolve. Comme beaucoup d’autres aujourd’hui, Savitri Devi peut seulement trouver une mauvaise consolation dans la croyance que ses idées, comme celles d’Akhenaton, ont valeur de vérité, quel que soit le jugement des masses.

De même, Savitri Devi fournit un exposé enthousiaste de la richesse et du statut impérial d’Akhenaton, dont elle affirme qu’ils sont la « récompense de la guerre » (p. 14), tout en affirmant ensuite le refus d’Akhenaton de maintenir un tel Etat, son principe du droit à l’autodétermination, et sa croyance que la guerre était « une offense envers Dieu » (p. 242). La position d’Akhenaton peut être excusée par le fait qu’il était né dans une certaine situation et qu’il fit de son mieux pour ne pas la laisser telle qu’il l’avait trouvée, et pour tenter d’améliorer sur le long terme l’état des choses tel qu’il le percevait. Savitri Devi, cependant, ne traite pas de cela dans le texte.

Mais la vision de Savitri Devi se trouve aussi en opposition avec son appui incessant à l’Allemagne nationale-socialiste, bien qu’elle ait écrit Fils du Soleil pendant les années de guerre. Nous devons bien sûr lui reconnaître d’abord la dignité d’avoir des idéaux supérieurs à ses affiliations politiques de compromis, de même que tout partisan d’un parti politique conserve une identité séparée de la politique du parti. Mais Savitri Devi reconnaît aussi la nécessité malheureuse d’une force de changement moralement portée au compromis dans son Europe lorsqu’elle remarque que « la violence est la loi de toute révolution dans le Temps » (p. 241, souligné dans l’original). Elle considère Akhenaton comme un homme « au-dessus du Temps », qui défend ses idéaux seulement pour les voir maudits, en contraste implicite avec Hitler (jusqu’ici implicitement mis en parallèle avec le pharaon), qui reconnaissait l’axiome précité (une ligne de pensée développée dans son ouvrage ultérieur The Lightning and the Sun). Savitri Devi n’expose pas explicitement ses idées sur le Lebensraum, bien qu’il semble que si certains de ses idéaux sont ouverts au compromis par nécessité politique, alors elle ne ferait pas d’exception pour l’expansion.

Elle tient aussi à montrer la continuité entre le culte solaire d’Akhenaton, l’hindouisme, et le national-socialisme moderne, en tentant d’établir divers liens biologiques avec les deux premières idées et en soulignant le fond culturel commun de la centralité du soleil, et de l’importance de la beauté, des castes et du principe. En fin de compte les connexions culturelles sont bien plus fortes que les biologiques, et sur le plan culturel le national-socialisme ne pouvait pas égaler ses prédécesseurs.

Savitri Devi envisage le remplacement de la relation brisée entre religion et Etat par une unité dans l’idée de la « religion de la race » (p. 288). Alors qu’elle approuve initialement un retour à une telle unité matérielle et spirituelle, elle le critique ensuite comme étant de portée trop étroite pour être fructueux. Elle le compare à un retour aux « dieux nationaux de jadis », qui étaient, notamment, ceux qui furent supplantés par la révolution d’Akhenaton. En fin de compte, Savitri Devi ne peut pas approuver un tel but ; s’il vaut peut-être mieux que les idées de ses « antagonistes humanitaires » (p. 288), il demeure un symbole plus étroit que celui de « l’homme », et peut donc permettre l’exploitation anthropocentrique de la nature ainsi que l’exploitation sélective des autres humains.

Une telle limitation imposée à la « Religion de la Vie » est indéfendable, et Savitri Devi préférerait plutôt l’autre voie, reconnaissant « les valeurs cosmiques comme l’essence de la religion » (p. 289). Cela semble similaire au rejet par Julius Evola de la vision biologique de la race par le national-socialisme, qu’il remplaça par un concept racial spirituel. Une telle vision, bien qu’elle jouait un rôle secondaire dans son courageux optimisme concernant le national-socialisme, nous montre que Savitri Devi tentait d’améliorer le mouvement qu’elle soutenait et qu’il ne la contraignait aucunement à limiter sa pensée.

Les complexités et les contradictions apparentes dans la pensée de Savitri Devi, particulièrement lorsqu’elles sont liées à ses convictions politiques, ne sont certainement pas des impasses et ne doivent pas nous conduire à rejeter sa pensée et à nous souvenir seulement de son action. Au contraire, elles doivent nous pousser à remettre en question notre conception de ses actions (et du contexte national-socialiste lui-même) afin de nous adapter à sa pensée. Vues sous cet angle, ce sont les convictions politiques de Savitri Devi qui nous apparaissent maintenant comme des anomalies ; elle consacra une foi incessante au mouvement national-socialiste d’après-guerre (qui n’aurait certainement pas pu approcher la vie d’après ses idéaux), finalement en vain, ce qui ne pouvait que ternir sa réputation en tant qu’écrivain.

L’exactitude historique de Fils du Soleil n’est pas d’une importance essentielle. Savitri Devi utilisa habilement l’histoire pour sélectionner et développer une religion unifiant les besoins rationnels et spirituels de l’humanité, tout en décrivant à son sommet un génie/héros digne de toutes les tentatives d’émulation. C’est la principale réussite du livre. Si l’obsession moderne de l’authenticité est forte, elle est finalement dépassée par l’obsession moderne pour l’originalité et la nouveauté. L’atonisme, bien sûr, n’a été adopté par personne. Mais son approche naturaliste et esthétique de la vie, et son absence de prescriptions morales, est une leçon inestimable pour les humains modernes. Le livre Fils du Soleil est en lui-même une œuvre de l’esprit solaire qu’il exalte. Akhenaton, Roi d’Egypte, et Savitri Devi peuvent tous deux nous enseigner la vérité selon laquelle la vie est un culte.

Notes

1. Titre d’une récente biographie : Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, Savitri Devi, la prêtresse d’Hitler, Akribeia 2000. Edition originale : New York University Press, 1998.

2. Titre original : A Son of God: The Life and Philosophy of Akhnaton, King of Egypt (London: Philosophical Publishing House, 1946), plus tard réédité sous le titre de Son of the Sun: The Life and Philosophy of Akhnaton, King of Egypt (San Jose, California: A.M.O.R.C., 1956).

3. René Guénon, La crise du monde moderne, Gallimard 1946. Traduction anglaise M. Pallis et R. Nicholson (London: Luzac, 1962), p. 72.

Source: http://savitridevi.org/article_brundsen_french.html [6]

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2011/06/la-vie-est-un-culte-savitri-devis-akhenaton-fils-du-soleil/

00:07 Publié dans Livre, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : tradition, traditions, traditionalisme, savitri devi, égypte antique, akhenaton, culte solaire, soleil, égyptologie, monothéisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 12 juillet 2012

The Fourth Political Theory

A Note from the Editor

Foreword by Alain Soral

Introduction: To Be or Not to Be?

1. The Birth of the Concept

2. Dasein as an Actor

3. The Critique of Monotonic Processes

4. The Reversibility of Time

5. Global Transition and its Enemies

6. Conservatism and Postmodernity

7. ‘Civilisation’ as an Ideological Concept

8. The Transformation of the Left in the Twenty-first Century

9. Liberalism and Its Metamorphoses

10. The Ontology of the Future

11. The New Political Anthropology

12. Fourth Political Practice

13. Gender in the Fourth Political Theory

14. Against the Postmodern World

Appendix I: Political Post-Anthropology

Appendix II: The Metaphysics of Chaos

00:05 Publié dans Livre, Nouvelle Droite, Synergies européennes, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : livre, alexandre douguine, russie, theorie politique, sciences politiques, politologie, nouvelle droite russe |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Modernità totalitaria

Modernità totalitaria

Ex: http://www.centrostudilaruna.it/

Augusto Del Noce individuò precocemente la diversità dei regimi a partito unico del Novecento, rispetto al liberalismo, nella loro natura “religiosa” e fortemente comunitaria. Vere religioni apocalittiche, ideologie fideistiche della redenzione popolare, neo-gnosticismi basati sulla realizzazione in terra del Millennio. Questa la sostanza più interna di quei movimenti, che in tempi e modi diversi lanciarono la sfida all’individualismo laico e borghese. Fascismo, nazionalsocialismo e comunismo furono uniti dalla concezione “totalitaria” della partecipazione politica: la sfera del privato andava tendenzialmente verso un progressivo restringimento, a favore della dimensione pubblica, politica appunto. E nella sua Nuova scienza della politica, Voegelin già nel 1939 accentrò il suo sguardo proprio su questo enigmatico riermergere dalle viscere dell’Europa di una sua antica vocazione: concepire l’uomo come zoòn politikòn, animale politico, che vive la dimensione dell’agorà, della assemblea politica, come la vera espressione dell’essere uomo. Un uomo votato alla vita di comunità, al legame, alla reciprocità, al solidarismo sociale, più di quanto non fosse incline al soddisfacimento dei suoi bisogni privati e personali.

Lo studio del Fascismo partendo da queste sue profonde caratteristiche sta ormai soppiantando le obsolete interpretazioni economiciste e sociologiche che avevano dominato nei decenni scorsi, inadatte a capire un fenomeno tanto variegato e composito, ma soprattutto tanto “subliminale” e agente negli immaginari della cultura popolare. In questo senso, la categoria “totalitarismo”, sotto la quale Hannah Arendt aveva a suo tempo collocato il nazismo e il comunismo, ma non il Fascismo (in virtù dell’assenza in quest’ultimo di un apparato di violenta repressione di massa), viene recuperata con altri risvolti: anche il Fascismo ebbe un suo aspetto “totalitario”, chiamò se stesso con questo termine, aspirò a una sua “totalità”, ma semplicemente volendo significare che il suo era un modello di coinvolgimento totale, una mobilitazione di tutte le energie nazionali, una generale chiamata a raccolta di tutto il popolo nel progetto di edificazione dello Stato Nuovo. Il totalitarismo fascista, insomma, non tanto come sistema repressivo e come organizzazione dello Stato di polizia, ma come sistema di aggregazione totale di tutti in tutte le sfere dell’esistenza, dal lavoro al tempo libero, dall’arte alla cultura. Il totalitarismo fascista non come arma di coercizione capillare, ma come macchina di conquista e promozione di un consenso che si voleva non passivo e inerte, ma attivo e convinto.

Un’analisi di questi aspetti viene ora effettuata dal libro curato da Emilio Gentile Modernità totalitaria. Il fascismo italiano (Laterza), in cui vari autori affrontano il tema da più prospettive: la religione politica, gli stili estetici, la divulgazione popolare, l’architettura, i rituali del Regime. Pur negli ondeggiamenti interpretativi, se ne ricava il quadro di un Fascismo che non solo non fu uno strumento reazionario in mano agli agenti politici oscurantisti dell’epoca, ma proprio al contrario fu l’espressione più tipica della modernità, manifestando certo anche talune disfunzioni legate alla società di massa, ma – all’opposto del liberalismo – cercando anche di temperarle costruendo un tessuto sociale solidarista che risultasse, per quanto possibile nell’era industriale e tecnologica, a misura d’uomo.

Un’analisi di questi aspetti viene ora effettuata dal libro curato da Emilio Gentile Modernità totalitaria. Il fascismo italiano (Laterza), in cui vari autori affrontano il tema da più prospettive: la religione politica, gli stili estetici, la divulgazione popolare, l’architettura, i rituali del Regime. Pur negli ondeggiamenti interpretativi, se ne ricava il quadro di un Fascismo che non solo non fu uno strumento reazionario in mano agli agenti politici oscurantisti dell’epoca, ma proprio al contrario fu l’espressione più tipica della modernità, manifestando certo anche talune disfunzioni legate alla società di massa, ma – all’opposto del liberalismo – cercando anche di temperarle costruendo un tessuto sociale solidarista che risultasse, per quanto possibile nell’era industriale e tecnologica, a misura d’uomo.

Diciamo subito che l’indagine svolta da Mauro Canali, uno degli autori del libro in parola, circa le tecniche repressive attuate dal Regime nei confronti degli oppositori politici, non ci convince. Si dice che anche il Fascismo eresse apparati atti alla denuncia, alla sorveglianza delle persone, alla creazione di uno stato di sospetto diffuso. Che fu dunque meno “morbido” di quanto generalmente si pensi.

E si citano organismi come la mitica “Ceka” (la cui esistenza nel ‘23-’24 non è neppure storicamente accertata), la staraciana “Organizzazione capillare” del ‘35-’36, il rafforzamento della Polizia di Stato, la figura effimera dei “prefetti volanti”, quella dei “fiduciari”, che insieme alle leggi “fascistissime” del ‘25-’26 avrebbero costituito altrettanti momenti di aperta oppure occulta coercizione. Vorremmo sapere se, ad esempio, la struttura di polizia degli Stati Uniti – in cui per altro la pena capitale viene attuata ancora oggi in misura non paragonabile a quella ristretta a pochissimi casi estremi durante i vent’anni di Fascismo – non sia molto più efficiente e invasiva di quanto lo sia stata quella fascista. Che, a cominciare dal suo capo Bocchini, elemento di formazione moderata e “giolittiana”, rimase fino alla fine in gran parte liberale. C’erano i “fiduciari”, che sorvegliavano sul comportamento politico della gente? Ma perchè, oggi non sorgono come funghi “comitati di vigilanza antifascista” non appena viene detta una sola parola che vada oltre il seminato? E non vengono svolte campagne di intimidazione giornalistica e televisiva nei confronti di chi, per qualche ragione, non accetta il sistema liberaldemocratico? E non si attuano politiche di pubblica denuncia e di violenta repressione nei confronti del semplice reato di opinione, su temi considerati a priori indiscutibili? E non esistono forse leggi europee che mandano in galera chi la pensa diversamente dal potere su certi temi?

Il totalitarismo fascista non va cercato nella tecnica di repressione, che in varia misura appartiene alla logica stessa di qualsiasi Stato che ci tenga alla propria esistenza. Vogliamo ricordare che anche di recente si è parlato di “totalitarismo” precisamente a proposito della società liberaldemocratica. Ad esempio, nel libro curato da Massimo Recalcati Forme contemporanee di totalitarismo (Bollati Boringhieri), si afferma apertamente l’esistenza del binomio «potere e terrore» che domina la società globalizzata. Una struttura di potere che dispone di tecniche di dominazione psico-fisica di straordinaria efficienza. Si scrive in proposito che la società liberaldemocratica globalizzata della nostra epoca è «caratterizzata da un orizzonte inedito che unisce una tendenza totalitaria – universalista appunto – con la polverizzzazione relativistica dell’Uno». Il dominio oligarchico liberale di fatto non ha nulla da invidiare agli strumenti repressivi di massa dei regimi “totalitari” storici, attuando anzi metodi di controllo-repressione che, più soft all’apparenza, si rivelano nei fatti di superiore tenuta. Quando si richiama l’attenzione sull’esistenza odierna di un «totalitarismo postideologico nelle società a capitalismo avanzato», sulla materializzazione disumanizzante della vita, sullo sfaldamento dei rapporti sociali a favore di quelli economici, si traccia il profilo di un totalitarismo organizzato in modo formidabile, che è in piena espansione ed entra nelle case e nel cervello degli uomini con metodi “terroristici” per lo più inavvertiti, ma di straordinaria resa pratica. Poche società – ivi comprese quelle totalitarie storiche –, una volta esaminate nei loro reali organigrammi, presentano un “modello unico”, un “pensiero unico”, un’assenza di controculture e di antagonismi politici, come la presente società liberale. La schiavizzazione psicologica al modello del profitto e l’obbligatoria sudditanza agli articoli della fede “democratica” attuano tali bombardamenti mass-mediatici e tali intimidazioni nei confronti dei comportamenti devianti, che al confronto le pratiche fasciste di isolamento dell’oppositore – si pensi al blandissimo regime del “confino di polizia” – appaiono bonari e paternalistici ammonimenti di epoche arcaiche.

Il totalitarismo fascista non va cercato nella tecnica di repressione, che in varia misura appartiene alla logica stessa di qualsiasi Stato che ci tenga alla propria esistenza. Vogliamo ricordare che anche di recente si è parlato di “totalitarismo” precisamente a proposito della società liberaldemocratica. Ad esempio, nel libro curato da Massimo Recalcati Forme contemporanee di totalitarismo (Bollati Boringhieri), si afferma apertamente l’esistenza del binomio «potere e terrore» che domina la società globalizzata. Una struttura di potere che dispone di tecniche di dominazione psico-fisica di straordinaria efficienza. Si scrive in proposito che la società liberaldemocratica globalizzata della nostra epoca è «caratterizzata da un orizzonte inedito che unisce una tendenza totalitaria – universalista appunto – con la polverizzzazione relativistica dell’Uno». Il dominio oligarchico liberale di fatto non ha nulla da invidiare agli strumenti repressivi di massa dei regimi “totalitari” storici, attuando anzi metodi di controllo-repressione che, più soft all’apparenza, si rivelano nei fatti di superiore tenuta. Quando si richiama l’attenzione sull’esistenza odierna di un «totalitarismo postideologico nelle società a capitalismo avanzato», sulla materializzazione disumanizzante della vita, sullo sfaldamento dei rapporti sociali a favore di quelli economici, si traccia il profilo di un totalitarismo organizzato in modo formidabile, che è in piena espansione ed entra nelle case e nel cervello degli uomini con metodi “terroristici” per lo più inavvertiti, ma di straordinaria resa pratica. Poche società – ivi comprese quelle totalitarie storiche –, una volta esaminate nei loro reali organigrammi, presentano un “modello unico”, un “pensiero unico”, un’assenza di controculture e di antagonismi politici, come la presente società liberale. La schiavizzazione psicologica al modello del profitto e l’obbligatoria sudditanza agli articoli della fede “democratica” attuano tali bombardamenti mass-mediatici e tali intimidazioni nei confronti dei comportamenti devianti, che al confronto le pratiche fasciste di isolamento dell’oppositore – si pensi al blandissimo regime del “confino di polizia” – appaiono bonari e paternalistici ammonimenti di epoche arcaiche.

Il totalitarismo fascista fu altra cosa. Fu la volontà di creare una nuova civiltà non di vertice ed oligarchica, ma col sostegno attivo e convinto tanto delle avanguardie politiche e culturali, quanto di masse fortemente organizzate e politicizzate. Si può parlare, in proposito, di un popolo italiano soltanto dopo la “nazionalizzazione” effettuata dal Fascismo. Il quale, bene o male, prese masse relegate nell’indigenza, nell’ignoranza secolare, nell’abbandono sociale e culturale, le strappò al loro miserabile isolamento, le acculturò, le vestì, le fece viaggiare per l’Italia, le mise a contatto con realtà sino ad allora ignorate – partecipazione a eventi comuni di ogni tipo, vacanze, sussidi materiali, protezione del lavoro, diritti sociali, garanzie sanitarie… – dando loro un orgoglio, fecendole sentire protagoniste, elevandole alla fine addirittura al rango di “stirpe dominatrice”. E imprimendo la forte sensazione di partecipare attivamente a eventi di portata mondiale e di poter decidere sul proprio destino… Questo è il totalitarismo fascista. Attraverso il Partito e le sue numerose organizzazioni, di una plebe semimedievale – come ormai riconosce la storiografia – si riuscì a fare in qualche anno, e per la prima volta nella storia d’Italia, un popolo moderno, messo a contatto con tutti gli aspetti della modernità e della tecnica, dai treni popolari alla radio, dall’auto “Balilla” al cinema.

Il totalitarismo fascista fu altra cosa. Fu la volontà di creare una nuova civiltà non di vertice ed oligarchica, ma col sostegno attivo e convinto tanto delle avanguardie politiche e culturali, quanto di masse fortemente organizzate e politicizzate. Si può parlare, in proposito, di un popolo italiano soltanto dopo la “nazionalizzazione” effettuata dal Fascismo. Il quale, bene o male, prese masse relegate nell’indigenza, nell’ignoranza secolare, nell’abbandono sociale e culturale, le strappò al loro miserabile isolamento, le acculturò, le vestì, le fece viaggiare per l’Italia, le mise a contatto con realtà sino ad allora ignorate – partecipazione a eventi comuni di ogni tipo, vacanze, sussidi materiali, protezione del lavoro, diritti sociali, garanzie sanitarie… – dando loro un orgoglio, fecendole sentire protagoniste, elevandole alla fine addirittura al rango di “stirpe dominatrice”. E imprimendo la forte sensazione di partecipare attivamente a eventi di portata mondiale e di poter decidere sul proprio destino… Questo è il totalitarismo fascista. Attraverso il Partito e le sue numerose organizzazioni, di una plebe semimedievale – come ormai riconosce la storiografia – si riuscì a fare in qualche anno, e per la prima volta nella storia d’Italia, un popolo moderno, messo a contatto con tutti gli aspetti della modernità e della tecnica, dai treni popolari alla radio, dall’auto “Balilla” al cinema.

Ecco dunque che il totalitarismo fascista appare di una specie tutta sua. Lungi dall’essere uno Stato di polizia, il Regime non fece che allargare alla totalità del popolo i suoi miti fondanti, le sue liturgie politiche, il suo messaggio di civiltà, il suo italianismo, la sua vena sociale: tutte cose che rimasero inalterate, ed anzi potenziate, rispetto a quando erano appannaggio del primo Fascismo minoritario, quello movimentista e squadrista. Giustamente scrive Emily Braun, collaboratrice del libro sopra segnalato, che il Fascismo fornì nel campo artistico l’esempio tipico della sua specie particolare di totalitarismo. Non vi fu mai un’arte “di Stato”. Quanti si occuparono di politica delle arti (nomi di straordinaria importanza a livello europeo: Marinetti, Sironi, la Sarfatti, Soffici, Bottai…) capirono «che l’estetica non poteva essere né imposta né standardizzata… il fascismo italiano utilizzava forme d’arte modernista, il che implica l’arte di avanguardia». Ma non ci fu un potere arcigno che obbligasse a seguire un cliché preconfezionato. Lo stile “mussoliniano” e imperiale si impose per impulso non del vertice politico, ma degli stessi protagonisti, «poiché gli artisti di regime più affermati erano fascisti convinti».

Queste cose oggi possono finalmente esser dette apertamente, senza timore di quella vecchia censura storiografica, che è stata per decenni l’esatto corrispettivo delle censure del tempo fascista. Le quali ultime, tuttavia, operarono in un clima di perenne tensione ideologica, di crisi mondiali, di catastrofi economiche, di guerre e rivoluzioni, e non di pacifica “democrazia”. Se dunque vi fu un totalitarismo fascista, esso è da inserire, come scrive Emilio Gentile, nel quadro dell’«eclettismo dello spirito» propugnato da Mussolini, che andava oltre l’ideologia, veicolando una visione del mondo totale.

* * *

Tratto da Linea del 27 marzo 2009.

00:05 Publié dans Histoire, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : totalitarisme, histoire, théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques, italie, années 20, années 30, fascisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Chant of the Templars - Salve Regina

Chant of the Templars - Salve Regina

00:05 Publié dans Musique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : musique, moyen âge, templiers, chevalerie, musique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 11 juillet 2012

Fascism, Anti-Fascism, and the Welfare State

Fascism, Anti-Fascism, and the Welfare State

Paul Gottfried

00:05 Publié dans Entretiens, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques, paul gottfried, fascisme, italie, années 20, années 30 |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 10 juillet 2012

Interview with Paul Gottfried

"Attack the System"

Interview with Paul Gottfried

00:18 Publié dans Entretiens | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : droite, gauche, paul gottfried, entretiens, etats-unis |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 09 juillet 2012

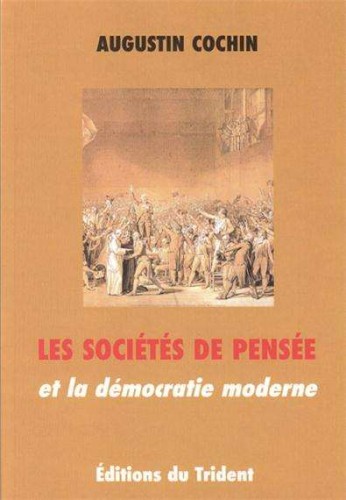

Augustin Cochin on the French Revolution

From Salon to Guillotine

Augustin Cochin on the French Revolution

By F. Roger Devlin

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Augustin Cochin

Organizing the Revolution: Selections From Augustin Cochin [2]

Translated by Nancy Derr Polin with a Preface by Claude Polin

Rockford, Ill.: Chronicles Press, 2007

The Rockford Institute’s publication of Organizing the Revolution marks the first appearance in our language of an historian whose insights apply not only to the French Revolution but to much of modern politics as well.

Augustin Cochin (1876–1916) was born into a family that had distinguished itself for three generations in the antiliberal “Social Catholicism” movement. He studied at the Ecole des Chartes and began to specialize in the study of the Revolution in 1903. Drafted in 1914 and wounded four times, he continued his researches during periods of convalescence. But he always requested to be returned to the front, where he was killed on July 8, 1916 at the age of thirty-nine.

Cochin was a philosophical historian in an era peculiarly unable to appreciate that rare talent. He was trained in the supposedly “scientific” methods of research formalized in his day under the influence of positivism, and was in fact an irreproachably patient and thorough investigator of primary archives. Yet he never succumbed to the prevailing notion that facts and documents would tell their own story in the absence of a human historian’s empathy and imagination. He always bore in mind that the goal of historical research was a distinctive type of understanding.

Both his archival and his interpretive labors were dedicated to elucidating the development of Jacobinism, in which he (rightly) saw the central, defining feature of the French Revolution. François Furet wrote: “his approach to the problem of Jacobinism is so original that it has been either not understood or buried, or both.”[1]

Most of his work appeared only posthumously. His one finished book is a detailed study of the first phase of the Revolution as it played out in Brittany: it was published in 1925 by his collaborator Charles Charpentier. He had also prepared (with Charpentier) a complete collection of the decrees of the revolutionary government (August 23, 1793–July 27, 1794). His mother arranged for the publication of two volumes of theoretical writings: The Philosophical Societies and Modern Democracy (1921), a collection of lectures and articles; and The Revolution and Free Thought (1924), an unfinished work of interpretation. These met with reviews ranging from the hostile to the uncomprehending to the dismissive.

“Revisionist” historian François Furet led a revival of interest in Cochin during the late 1970s, making him the subject of a long and appreciative chapter in his important study Interpreting the French Revolution and putting him on a par with Tocqueville. Cochin’s two volumes of theoretical writings were reprinted shortly thereafter by Copernic, a French publisher associated with GRECE and the “nouvelle droit.”

The book under review consists of selections in English from these volumes. The editor and translator may be said to have succeeded in their announced aim: “to present his unfinished writings in a clear and coherent form.”

Between the death of the pioneering antirevolutionary historian Hippolyte Taine in 1893 and the rise of “revisionism” in the 1960s, study of the French Revolution was dominated by a series of Jacobin sympathizers: Aulard, Mathiez, Lefevre, Soboul. During the years Cochin was producing his work, much public attention was directed to polemical exchanges between Aulard, a devotee of Danton, and his former student Mathiez, who had become a disciple of Robespierre. Both men remained largely oblivious to the vast ocean of assumptions they shared.

Cochin published a critique of Aulard and his methods in 1909; an abridged version of this piece is included in the volume under review. Aulard’s principal theme was that the revolutionary government had been driven to act as it did by circumstance:

This argument [writes Cochin] tends to prove that the ideas and sentiments of the men of ’93 had nothing abnormal in themselves, and if their deeds shock us it is because we forget their perils, the circumstances; [and that] any man with common sense and a heart would have acted as they did in their place. Aulard allows this apology to include even the very last acts of the Terror. Thus we see that the Prussian invasion caused the massacre of the priests of the Abbey, the victories of la Rochejacquelein [in the Vendée uprising] caused the Girondins to be guillotined, [etc.]. In short, to read Aulard, the Revolutionary government appears a mere makeshift rudder in a storm, “a wartime expedient.” (p. 49)

Aulard had been strongly influenced by positivism, and believed that the most accurate historiography would result from staying as close as possible to documents of the period; he is said to have conducted more extensive archival research than any previous historian of the Revolution. But Cochin questioned whether such a return to the sources would necessarily produce truer history:

Mr. Aulard’s sources—minutes of meetings, official reports, newspapers, patriotic pamphlets—are written by patriots [i.e., revolutionaries], and mostly for the public. He was to find the argument of defense highlighted throughout these documents. In his hands he had a ready-made history of the Revolution, presenting—beside each of the acts of “the people,” from the September massacres to the law of Prairial—a ready-made explanation. And it is this history he has written. (p. 65)

In fact, says Cochin, justification in terms of “public safety” or “self- defense” is an intrinsic characteristic of democratic governance, and quite independent of circumstance:

In fact, says Cochin, justification in terms of “public safety” or “self- defense” is an intrinsic characteristic of democratic governance, and quite independent of circumstance:

When the acts of a popular power attain a certain degree of arbitrariness and become oppressive, they are always presented as acts of self-defense and public safety. Public safety is the necessary fiction in democracy, as divine right is under an authoritarian regime. [The argument for defense] appeared with democracy itself. As early as July 28, 1789 [i.e., two weeks after the storming of the Bastille] one of the leaders of the party of freedom proposed to establish a search committee, later called “general safety,” that would be able to violate the privacy of letters and lock people up without hearing their defense. (pp. 62–63)

(Americans of the “War on Terror” era, take note.)

But in fact, says Cochin, the appeal to defense is nearly everywhere a post facto rationalization rather than a real motive:

Why were the priests persecuted at Auch? Because they were plotting, claims the “public voice.” Why were they not persecuted in Chartes? Because they behaved well there.

How often can we not turn this argument around?

Why did the people in Auch (the Jacobins, who controlled publicity) say the priests were plotting? Because the people (the Jacobins) were persecuting them. Why did no one say so in Chartes? Because they were left alone there.

In 1794 put a true Jacobin in Caen, and a moderate in Arras, and you could be sure by the next day that the aristocracy of Caen, peaceable up till then, would have “raised their haughty heads,” and in Arras they would go home. (p. 67)

In other words, Aulard’s “objective” method of staying close to contemporary documents does not scrape off a superfluous layer of interpretation and put us directly in touch with raw fact—it merely takes the self-understanding of the revolutionaries at face value, surely the most naïve style of interpretation imaginable. Cochin concludes his critique of Aulard with a backhanded compliment, calling him “a master of Jacobin orthodoxy. With him we are sure we have the ‘patriotic’ version. And for this reason his work will no doubt remain useful and consulted” (p. 74). Cochin could not have foreseen that the reading public would be subjected to another half century of the same thing, fitted out with ever more “original documentary research” and flavored with ever increasing doses of Marxism.

But rather than attending further to these methodological squabbles, let us consider how Cochin can help us understand the French Revolution and the “progressive” politics it continues to inspire.

It has always been easy for critics to rehearse the Revolution’s atrocities: the prison massacres, the suppression of the Vendée, the Law of Suspects, noyades and guillotines. The greatest atrocities of the 1790s from a strictly humanitarian point of view, however, occurred in Poland, and some of these were actually counter-revolutionary reprisals. The perennial fascination of the French Revolution lies not so much in the extent of its cruelties and injustices, which the Caligulas and Genghis Khans of history may occasionally have equaled, but in the sense that revolutionary tyranny was something different in kind, something uncanny and unprecedented. Tocqueville wrote of

something special about the sickness of the French Revolution which I sense without being able to describe. My spirit flags from the effort to gain a clear picture of this object and to find the means of describing it fairly. Independently of everything that is comprehensible in the French Revolution there is something that remains inexplicable.

Part of the weird quality of the Revolution was that it claimed, unlike Genghis and his ilk, to be massacring in the name of liberty, equality, and fraternity. But a deeper mystery which has fascinated even its enemies is the contrast between its vast size and force and the negligible ability of its apparent “leaders” to unleash or control it: the men do not measure up to the events. For Joseph de Maistre the explanation could only be the direct working of Divine Providence; none but the Almighty could have brought about so great a cataclysm by means of such contemptible characters. For Augustin Barruel it was proof of a vast, hidden conspiracy (his ideas have a good claim to constitute the world’s original “conspiracy theory”). Taine invoked a “Jacobin psychology” compounded of abstraction, fanaticism, and opportunism.

Cochin found all these notions of his antirevolutionary predecessors unsatisfying. Though Catholic by religion and family background, he quite properly never appeals to Divine Providence in his scholarly work to explain events (p. 71). He also saw that the revolutionaries were too fanatical and disciplined to be mere conspirators bent on plunder (pp. 56–58; 121–122; 154). Nor is an appeal to the psychology of the individual Jacobin useful as an explanation of the Revolution: this psychology is itself precisely what the historian must try to explain (pp. 60–61).

Cochin viewed Jacobinism not primarily as an ideology but as a form of society with its own inherent rules and constraints independent of the desires and intentions of its members. This central intuition—the importance of attending to the social formation in which revolutionary ideology and practice were elaborated as much as to ideology, events, or leaders themselves—distinguishes his work from all previous writing on the Revolution and was the guiding principle of his archival research. He even saw himself as a sociologist, and had an interest in Durkheim unusual for someone of his Catholic traditionalist background.

The term he employs for the type of association he is interested in is société de pensée, literally “thought-society,” but commonly translated “philosophical society.” He defines it as “an association founded without any other object than to elicit through discussion, to set by vote, to spread by correspondence—in a word, merely to express—the common opinion of its members. It is the organ of [public] opinion reduced to its function as an organ” (p. 139).

It is no trivial circumstance when such societies proliferate through the length and breadth of a large kingdom. Speaking generally, men are either born into associations (e.g., families, villages, nations) or form them in order to accomplish practical ends (e.g., trade unions, schools, armies). Why were associations of mere opinion thriving so luxuriously in France on the eve of the Revolution? Cochin does not really attempt to explain the origin of the phenomenon he analyzes, but a brief historical review may at least clarify for my readers the setting in which these unusual societies emerged.

About the middle of the seventeenth century, during the minority of Louis XIV, the French nobility staged a clumsy and disorganized revolt in an attempt to reverse the long decline of their political fortunes. At one point, the ten year old King had to flee for his life. When he came of age, Louis put a high priority upon ensuring that such a thing could never happen again. The means he chose was to buy the nobility off. They were relieved of the obligations traditionally connected with their ancestral estates and encouraged to reside in Versailles under his watchful eye; yet they retained full exemption from the ruinous taxation that he inflicted upon the rest of the kingdom. This succeeded in heading off further revolt, but also established a permanent, sizeable class of persons with a great deal of wealth, no social function, and nothing much to do with themselves.

The salon became the central institution of French life. Men and women of leisure met for gossip, dalliance, witty badinage, personal (not political) intrigue, and discussion of the latest books and plays and the events of the day. Refinement of taste and the social graces reached an unusual pitch. It was this cultivated leisure class which provided both setting and audience for the literary works of the grand siècle.

The common social currency of the age was talk: outside Jewish yeshivas, the world had probably never beheld a society with a higher ratio of talk to action. A small deed, such as Montgolfier’s ascent in a hot air balloon, could provide matter for three years of self-contented chatter in the salons.

Versailles was the epicenter of this world; Paris imitated Versailles; larger provincial cities imitated Paris. Eventually there was no town left in the realm without persons ambitious of imitating the manners of the Court and devoted to cultivating and discussing whatever had passed out of fashion in the capital two years earlier. Families of the rising middle class, as soon as they had means to enjoy a bit of leisure, aspired to become a part of salon society.

Toward the middle of the eighteenth century a shift in both subject matter and tone came over this world of elegant discourse. The traditional saloniste gave way to the philosophe, an armchair statesman who, despite his lack of real responsibilities, focused on public affairs and took himself and his talk with extreme seriousness. In Cochin’s words: “mockery replaced gaiety, and politics pleasure; the game became a career, the festivity a ceremony, the clique the Republic of Letters” (p. 38). Excluding men of leisure from participation in public life, as Louis XIV and his successors had done, failed to extinguish ambition from their hearts. Perhaps in part by way of compensation, the philosophes gradually

created an ideal republic alongside and in the image of the real one, with its own constitution, its magistrates, its common people, its honors and its battles. There they studied the same problems—political, economic, etc.—and there they discussed agriculture, art, ethics, law, etc. There they debated the issues of the day and judged the officeholders. In short, this little State was the exact image of the larger one with only one difference—it was not real. Its citizens had neither direct interest nor responsible involvement in the affairs they discussed. Their decrees were only wishes, their battles conversations, their studies games. It was the city of thought. That was its essential characteristic, the one both initiates and outsiders forgot first, because it went without saying. (pp. 123–24)

Part of the point of a philosophical society was this very seclusion from reality. Men from various walks of life—clergymen, officers, bankers—could forget their daily concerns and normal social identities to converse as equals in an imaginary world of “free thought”: free, that is, from attachments, obligations, responsibilities, and any possibility of failure.

In the years leading up to the Revolution, countless such organizations vied for followers and influence: Amis Réunis, Philalèthes, Chevaliers Bienfaisants, Amis de la Verité, several species of Freemasons, academies, literary and patriotic societies, schools, cultural associations and even agricultural societies—all barely dissimulating the same utopian political spirit (“philosophy”) behind official pretenses of knowledge, charity, or pleasure. They “were all more or less connected to one another and associated with those in Paris. Constant debates, elections, delegations, correspondence, and intrigue took place in their midst, and a veritable public life developed through them” (p. 124).

Because of the speculative character of the whole enterprise, the philosophes’ ideas could not be verified through action. Consequently, the societies developed criteria of their own, independent of the standards of validity that applied in the world outside:

Whereas in the real world the arbiter of any notion is practical testing and its goal what it actually achieves, in this world the arbiter is the opinion of others and its aim their approval. That is real which others see, that true which they say, that good of which they approve. Thus the natural order is reversed: opinion here is the cause and not, as in real life, the effect. (p. 39)

Many matters of deepest concern to ordinary men naturally got left out of discussion: “You know how difficult it is in mere conversation to mention faith or feeling,” remarks Cochin (p. 40; cf. p. 145). The long chains of reasoning at once complex and systematic which mark genuine philosophy—and are produced by the stubborn and usually solitary labors of exceptional men—also have no chance of success in a society of philosophes (p. 143). Instead, a premium gets placed on what can be easily expressed and communicated, which produces a lowest-common-denominator effect (p. 141).

The philosophes made a virtue of viewing the world surrounding them objectively and disinterestedly. Cochin finds an important clue to this mentality in a stock character of eighteenth-century literature: the “ingenuous man.” Montesquieu invented him as a vehicle for satire in the Persian Letters: an emissary from the King of Persia sending witty letters home describing the queer customs of Frenchmen. The idea caught on and eventually became a new ideal for every enlightened mind to aspire to. Cochin calls it “philosophical savagery”:

Imagine an eighteenth-century Frenchman who possesses all the material attainments of the civilization of his time—cultivation, education, knowledge, and taste—but without any of the real well-springs, the instincts and beliefs that have created and breathed life into all this, that have given their reason for these customs and their use for these resources. Drop him into this world of which he possesses everything except the essential, the spirit, and he will see and know everything but understand nothing. Everything shocks him. Everything appears illogical and ridiculous to him. It is even by this incomprehension that intelligence is measured among savages. (p. 43; cf. p. 148)

In other words, the eighteenth-century philosophes were the original “deracinated intellectuals.” They rejected as “superstitions” and “prejudices” the core beliefs and practices of the surrounding society, the end result of a long process of refining and testing by men through countless generations of practical endeavor. In effect, they created in France what a contributor to this journal has termed a “culture of critique”—an intellectual milieu marked by hostility to the life of the nation in which its participants were living. (It would be difficult, however, to argue a significant sociobiological basis in the French version.)