All great cultures and nations that have arisen, and all those who are to come will one day decline and pass into history. This cyclical understanding is near universal. Societies do not decline however, entirely without an awareness of their decline. Like any organism that is sickly or wounded, society will show the symptoms of its decay, sometimes before it is too late and the course is not irreversible. History has given us many examples of men who, like canaries in a mine, warned of impending danger oftentimes losing their lives in the process. One of the finest examples is that of Agis IV, the Agiad king of Sparta. But first, a few remarks are necessary on the Spartan constitution and government before his time.

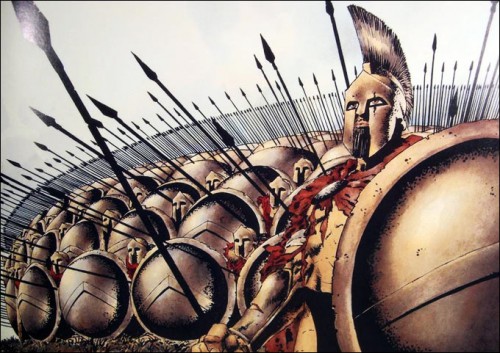

The Spartan constitution is perhaps one of the most unique in history. The Spartan state was for some time indistinguishable from the rest of the Greek poleis; its unique constitution was eventually decreed under one of the legendary sages of Greece, Lycurgus. Lycurgus aimed to make Sparta a militarized society that valued discipline, order and a strict hierarchy. The Spartan citizens were a warrior class able to form up at a moments notice to meet any threats. Spartans were known for their disdain for material wealth, their military prowess, and their system of a dual monarchy. Two kingly houses, the Argiad and the Eurypontid, traced their ancestry back to Hercules ruled Sparta for the length of its independent history, and were supported by five ephors, elected officials who were only permitted to remain in power for a year. Below these were a council of elders and a popular assembly. Sparta followed a strict hierarchy, only Spartan youths and a select few free men and helots were permitted to citizenship, and to be a Spartan meant to swear off trades or engage in any work outside of martial training and warfare, or travel outside of Sparta, unless on campaign or specifically permitted. The men were required to dine together from their adulthood to around their sixtieth year. Agricultural work, trade and craftsmanship were all done by either helots, the lowest class in the Spartan state, or perioeci, freemen without the privileges of citizenship. Despite its harsh nature, Spartan society proved resilient and Sparta remained one of the dominant states in Greece until the time of Alexander. Spartan soldiery enjoyed a reputation of near invincibility for most of this period, and even after its decline Spartans were highly prized as mercenaries.

Aristotle criticized the Spartan constitution in his Politics, writing that while it was suitable in war, it did not prepare Spartans to live in peace, and thus the very success of Sparta against Athens led to its ruin, through the influx of material wealth from its defeated foe. With no understanding of enjoying luxury in moderation, Sparta sunk into decadence. Its population had fallen perilously low, and the pool of citizens was shrinking to the point where only seven hundred families were considered Spartan, and of these only one hundred remained that possessed land. This was partially on account of a on the change in inheritance law, where before it would go to the son, after it could go to whomever one desired.

Agis was born into the wealthiest of the Spartan families and lived his early life in the luxury which Spartans had grown accustomed too, but was raised with a respect for Sparta’s great history, and its old ways which he resolved, before the age of 20 to adopt. He forsook the luxurious habits of his peers and donned the coarse cloak of the Spartans of old, and sought in every way to live by the laws of Lycurgus. He had his opportunity when he succeeded his father on the throne in 245 BC.

Those most opposed to Agis IV reforms were the older, established men who were used to their comfort and luxury and, to quote Plutarch,

“The young men, as he found, quickly and beyond his expectations gave ear to him, and stripped themselves for the contest in behalf of virtue, like him casting aside their old ways of living as worn-out garments in order to attain liberty. But most of the older men, since they were now far gone in corruption, feared and shuddered at the name of Lycurgus as if they had run away from their master and were being led back to him, and they upbraided Agis for bewailing the present state of affairs and yearning after the ancient dignity of Sparta..”

Spartan women also tended to oppose his moves, as Spartan society gave them a unique control over the affairs of family estates, and thus, the riches of the family. They enlisted Leonidas II, the co king to their cause. Leonidas was himself given to luxury even beyond the rest, having been raised in the Seleucid court. He needed very little persuading in the matter and opposed Agis’ motions on the grounds of the disorder they would cause. Agis had key supporters, however, in his mother and grandmother, along with his uncle Agesilaus, and the ephor Lysander. With their assistance, he presented a motion to the council of elders calling for drastic reforms to bring Sparta back in accordance with the laws of Lycurgus, including a cancellation of all debts, redistribution of land into equal parts among the Spartans with the rest going to free men, the elevating of more of the free men to citizenship class to alleviate their dangerously low numbers. Agis IV gained even more fervent support when he vowed to redistribute and part with his own lands and wealth first and foremost, with his family doing the same. He managed to banish Leonidas on the grounds of both his foreign upbringing and foreign wife, both strictly forbidden by the laws of Lycurgus, and be replaced with his son in law, Cleombrotus, a man far more amendable to Agis’ aims. Some in his camp around his uncle were eager to see Leonidas killed, but Agis, discovering this sent men to guard and escort Leonidas to safety. A more cunning, less morally scrupulous man than Agis would have no doubt allowed the conspirators to kill Leonidas, and be rid of a dangerous rival. This mercy would later contribute to his undoing.

With the removal of Leonidas and the support of ephors, he pushed through his reforms until being summoned to war as part of his alliance with Aratas and the Achaean League. He collected an army and departed, eager to take an opportunity to display the reinvigorated spirit of Sparta. His men, it is said eagerly marched behind the young king, and were marveled at by their allies for their discipline, order, and cheery disposition. While ultimately the campaign ended before any major engagement, Agis IV did Sparta no dishonor in this, fulfilling what was required of him by treaty and winning the respect of Aratas his fellow commander. Unfortunately, during his time away, he left the affairs of state in the hands of Agesilaus. While Agesilaus was a well regarded man, he had ulterior motives for supporting his nephew’s reforms; he had incurred significant debts that the reforms the king was pushing through would cancel out. He endeavored to push for the debt cancellation but delay the redistribution of land with the argument that the reforms should be carried out at a gradual pace, but once the first part was enacted, continually stalled on the second. This caused much chaos and disorder and left the Spartans yearning even for a return of Leonidas. At the same time, Lysander and Mandrocleides’ terms of office as ephors expired, and the new ephors were opposed to Agis’ designs. Leonidas was able to return unopposed with mercenaries at his back. Agis and Cleombrotus sensed the danger and fled to sanctuaries of Athena and Poseidon respectively. Leonidas wasted no time deposing his son in law, exiling him rather than executing him at the behest of his daughter, leaving only Agis to deal with. Agis was protected for a time by some companions, who would escort him from the sanctuary to the public baths. This continued until these same companions persuaded by one Amphares, under pressure from Leonidas, betrayed him and dragged him to prison.

From his cell, Agis was ordered to defend himself and accused of bring disorder into Sparta. Agis refused to denounce his conduct, insisting that he had acted of his own volition, with Lycurgus as his only inspiration. He stated that though he suffer the most severe punishment, he would not be made to renounce so noble an idea. He was sentenced to death accordingly, though those sent to execute him were reluctant to do so, for to spill the blood of a king and a man of such nature was a dishonor even to Leonidas’ hirelings. One Damochares stepped forward for Leonidas and the ephors were eager that he be dispatched with haste as people had gathered by the prison, including Agis’ mother and grandmother demanding he be tried before the people, rather than Leonidas’ selected men.

Agis was thus led to the execution chamber, and, according to Plutarch;

Agis was thus led to the execution chamber, and, according to Plutarch;

“saw one of the officers shedding tears of sympathy for him. “My man,” said he, “cease weeping; for even though I am put to death in this lawless and unjust manner, I have the better of my murderers.” And saying these words, he offered his neck to the noose without hesitation.”

With this, Agis was executed via strangulation. His mother and grandmother were executed at the same spot after; both faced their end with bravery. Before her death, his mother is said to have uttered: “My son, it was thy too great regard for others, and thy gentleness and humanity, which has brought thee to ruin, us as well.” Though Agis had failed, all was not lost to Sparta. Leonidas arranged for his widow to marry his son Cleomenes. Despite the circusmtances, the two developed mutual affection and the young Cleomenes was deeply impressed by Agis’ project. Upon taking the throne he enacted reforms himself, and led a resurgent Sparta against its enemies, becoming the last great king of Sparta.

Agis’s kingship only lasted four brief years yet he inspired one of his successor kings, Plutarch and countless others in later generations. Our interest in him comes from his embodiment of the ideal qualities of a true king. He wished to reform Spartan society and to bring it back into accordance with the laws of its illustrious past. His land reforms, redistribution and debt cancellation in other hands could have been seen as simply cheap populism meant to gain support and power. What separates Agis from a populist demagogue was his sincere desire to elevate Sparta spiritually. He wished to shake off its decadence and revive its old love of discipline, order and disdain for material gain. Sparta’s economic condition was of secondary importance. While his reforms would certainly have greatly improved the lot for its citizens and freemen, what was more important was they would restore Sparta’s honor and ensure its viability as a state long after his death. He was more than happy to sacrifice wealth and even his life for this goal, when he could have at any point ceased or compromised. In his personal conduct as well he showed nobility to a fault- never resorting to foul means or dishonorable acts to see his plans through. Even at his end, Plutarch seems to imply the ephors gave him the opportunity to pass the blame to his uncle Agesilaus or the ephor Lysander for the chaotic state of affairs. He took full responsibility rather than speak against either man. He could have been forgiven for betraying Agesilaus to Leonidas, considering how much of the blame for his ruin rested on the shoulders of that man, yet he refused to do so, such was his character. If there were any faults in the man, it was naivety and good nature, and these can hardly be called faults.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

By the 6

By the 6

„Mit diesem imposanten Werk liegt eine überzeugende Neuinterpretation des Wirkens von Karl Haushofer vor: Der globale Ansatz seiner Theorien wird durch die Fokussierung auf Japan und die dortige Rezeption von Haushofers Gedankenwelt erstmals deutlich herausgearbeitet. Haushofer wird überzeugend als theoretischer Wegbereiter nationalsozialistischer Eurasienpolitik beschrieben, der das Drehbuch zum ‚Dreimächtepakt’ verfasste, und mit seinen Werken in Japan sogar auf die Kriegsplanung einwirkte. Das ausgebreitete Detailwissen ist beeindruckend, die Interpretation neu und auch die sprachliche Umsetzung geglückt.“

„Mit diesem imposanten Werk liegt eine überzeugende Neuinterpretation des Wirkens von Karl Haushofer vor: Der globale Ansatz seiner Theorien wird durch die Fokussierung auf Japan und die dortige Rezeption von Haushofers Gedankenwelt erstmals deutlich herausgearbeitet. Haushofer wird überzeugend als theoretischer Wegbereiter nationalsozialistischer Eurasienpolitik beschrieben, der das Drehbuch zum ‚Dreimächtepakt’ verfasste, und mit seinen Werken in Japan sogar auf die Kriegsplanung einwirkte. Das ausgebreitete Detailwissen ist beeindruckend, die Interpretation neu und auch die sprachliche Umsetzung geglückt.“