Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

Left/Right dichotomies in the representation of female militants in the movies The Baader Meinhof Complex (2008) and A Student named Alexander (2011).

‘Although typically villainous, or at least morally ambiguous, and always associated with a sense of mystification and unease, femme fatales have also appeared as heroines in some stories . . .’

— Mary Ann Doane

From the Levantine Lilith to the Celtic Morgan Le Fay; and from Theda Bara’s vamp in Hollywood’s A Fool There Was to Eva Green in Sin City: A Dame to Kill For, the notion of the fille d’Eve tantalizes us. In sociological terms the notion of diabolic women is potent with misogyny, witchcraft and the negative aspects of anima, how woman appears to man, from the Jungian viewpoint. To take the cinematic angle, licentious dames mean box office receipts, plain and simple. Roger Vadim’s And God Created Woman (1957), starring starlet Brigitte Bardot and Jean-Jacques Beineix’s Betty Blue (1986) with Beatrice Dalle being just two cases that prove the point.

Stereotypes range from enchantress to succubus, haunting our consciousness in different guises, such as the spectral Cathy from Emily Brontë’s classic Wuthering Heights (1847) or the more malign character of Rebecca in Daphne du Maurier’s 1938 book of the same name. As Charles Baudelaire (1821-67) (1), Once mused, ‘The strange thing about woman — her pre-ordained fate — is that she is simultaneously the sin and the Hell that punishes it’. Indeed, a whole academic industry has grown up deconstructing such iconography with writers like Toni Bentley’s Sisters of Salome (2002); Bram Dijkstra’s Idols of Perversity: Fantasies of Feminine Evil in Fin-de-Siècle Culture (1986); and Elizabeth K. Mix’s Evil by Design: The Creation and Marketing of the Femme Fatale in 19th-Century France (2006) leading the way.

Baudelaire’s own magnum opus Les Fleurs du Mal (1857) epitomizes the dichotomy perfectly. The schizophrenia embodied in his poetic creations, Jean Duval (Black Venus) and Apollonie Sabatier (White Venus), both mirroring and reinforcing some male fantasies about women’s sexuality in the closing decades of the nineteenth century. The dialectics of Serpent Culture and Snake Charmer sensuality, so beautifully carved in Auguste Clesinger’s (picture here above) writhing milk white statue Woman Bitten by a Snake (1847), a representation of Apollonie Sabatier currently on display in the Musée d’Orsay, raises the question, is she squirming in agony or riding a paroxysm of pleasure from the venomous bite?

Moving beyond the arts, literature and film to the political milieu? What evidence do we have for Femme Fatale’s within the Left/Right dichotomy? There is certainly a colorful cast of charismatic characters to choose from: Inessa Armand, Rosa Luxemburg, Clara Zetkin, Jiang Quing, Bernardine Dohrn, and Angela Davis to name but a few on the left-side. Unity Mitford, Savitri Devi, Alessandra Mussolini, Beate Zschape, Yevgenia Khasis, and Marine Le Pen, as examples from the right side of the aisle.

It is my intention to dismiss empathetic documentaries like Confrontation Paris, 68, The Weather Underground (2002) and hatchet-job investigative journalism like Turning Point’s Inside the Hate Conspiracy (1995) about America’s The Order without further comment. Instead arguing that there are few, if any, historically accurate, unbiased and insightful fictional or factional celluloid representations of female (or for that matter male) political militants in circulation. Instead, what we are served up are predictable stereo-types and clichéd cartoonesque parodies, completely aligned with the liberal left Euro-68 ethos, wherein, a mélange of well-meaning but misguided (and always attractive) socialist idealists try to change society for the better, juxtaposed with psychopathic rightist harridans, or male sexual inadequates, portrayed as vacuous outsiders, decidedly uncool and devoid of social capital.

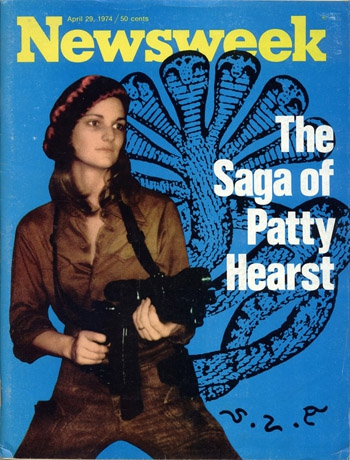

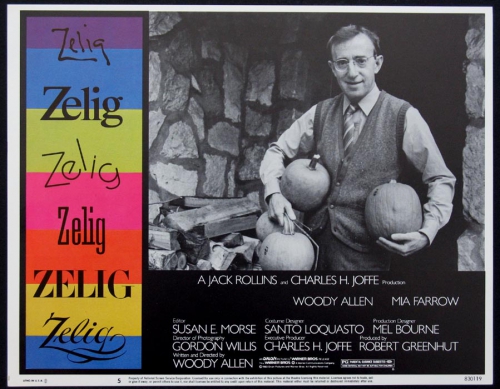

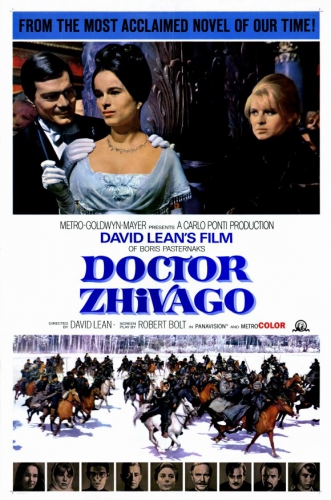

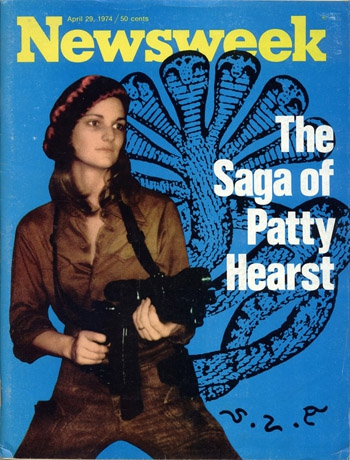

Indicative examples of the genre being, from the left: The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum (1975), The Underground (1976), Running on Empty (1988), What to Do in Case of Fire (2002), Baader (2002), The Dreamers (2004), Guerilla — The Taking of Patty Hearst (2005), Regular Lovers (2005), Mesrine: Killer Instinct (2008), Che (2008), The Baader Meinhof Complex (2008), The Company You Keep (2012) and Something in the Air (2013). As opposed to the more objectionable characterizations of rightists in productions like The Day of the Jackal (1973), The Odessa File (1974), The Boys from Brazil (1978), Betrayed (1988), Siege at Ruby Ridge (1996), Brotherhood of Murder (1999), and A Student named Alexander (2011).

For the sake of argument I have been deliberately selective and will focus specifically on Uli Edels’s Baader Meinhof Complex and Enzo De Camillis’s fifteen minute short A Student named Alexander. Risking the approbation of cultural commentators by possibly extrapolating too general a hypothesis from too limited a sample, I nevertheless press my case, that the content, reaction and intent of both these films exemplify the paradox of Left/Right caricatures in the entertainment media.

For the sake of argument I have been deliberately selective and will focus specifically on Uli Edels’s Baader Meinhof Complex and Enzo De Camillis’s fifteen minute short A Student named Alexander. Risking the approbation of cultural commentators by possibly extrapolating too general a hypothesis from too limited a sample, I nevertheless press my case, that the content, reaction and intent of both these films exemplify the paradox of Left/Right caricatures in the entertainment media.

Recipient of 6.5 million euros from various film boards and Golden Globe and Oscar nominee in the Best Foreign Film category, The Baader Meinhof Complex, rode the wave of resurgent seventies retro, a movie filled with baby boomer nostalgia for the late sixties and early seventies. Simpler times, when idealism meant Sartre, anti-Vietnam protest, Che Guevara posters, and smoking pot in bedsits listing to the sitar music of Ravi Shankar.

The movies all-star cast includes Martina Gedeck as Ulrike Meinhof, Moritz Bleibtreu as Andreas Baader, Johanna Wokalek as Gudrun Ensslin, and Alexandra Maria Lara as Petra Schelm. All of whom had already or were soon to appear in mainstream feature films like: The Lives of Others, Run Lola Run, The Good Shepherd, Pope Joan, North Face, Control, and Downfall.

The action begins with the 1967 Schah-Besuch mass street protest in Berlin against the Shah of Iran. Mohamed Reza Pahlavi’s supporters are depicted launching an unprovoked attack on the anti-Pahlavi elements, resulting in running battles and the shooting of Benno Ohnesorg in Krumme Strasse 66, by what appears to be a reactionary police officer, Karl-Heinz Kurras, but who was in reality a card-carrying member of the Communist Party acting as an undercover operative for the East German Stasi.

We are then treated to scenes where Maoist students hold packed meetings, intercut with footage of American warplanes strafing and bombing Vietnamese peasants. Rapidly followed by ‘Red’ Rudi Dutschke (3) of 2nd June Movement fame (named after the aforementioned riot) raising his clenched fist, the Messianic leader of the Gramscian ‘Long March through the Institutions’.

Dutschke is elevated to intellectual martyr status when he is mercilessly gunned down in the street by Josef Bachmann, portrayed by actor Tom Schilling, whose cinematic appearance is clearly meant to conjure images of a Hitler Youth or a die-hard Werewolf with a chronic nervous disposition. Which is ironic given that the Baader Meinhof gang and the various later incarnations of the Red Army Faction relied so heavily on a group linked to Heidelberg University, the Sozialistisches Patientiv Kollektiv (Socialist Patient Collective), an organization that sought to convince neurotics and the insane that they were not wrong, it was the system that was wrong, and social revolution was the cure.

‘Shooting is like fucking,’ screams Baader as Bernd Eichinger’s screenplay and Rainer Klausman’s hypnotic lens combine to present a seductive and fast paced cine-orgasm of free love, role model women for Second Wave feminism, cool people smoking cigarettes in coffee shops debating Marxist dialectics, driving around in BMWs, burning department stores, shooting up road signs, Robin Hood bank robbers sunning themselves topless in PLO training camps, liberating captives in a back glow of exploding gelignite and the swashbuckling rat-a-tat of 9mm shells.

Even the capture of Baader, Ensslin, and Meinhof for their egregious crimes are contextually ambiguous. Baader, in a scene more reminiscent of the end of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) than the original television footage of his stand-off with police; Meinhof, kicking and screaming in outrage, rather than the deflated, depressed, and played-out fantasist she was; and Ensslin, by pure chance, when a shop assistant notices a gun in her handbag. Another martyr is then injected into the story as Holger Meins (4) is depicted a la Bobby Sands (5), going on hunger strike and the subsequent trial in Stammheim (6), more Monty Python farce than a serious attempt to enact justice.

One is left in doubt as to where the audience’s sympathy is meant to lie. Especially, with our ever heroic protagonists making fun of the trial judges and gaining increasing support from those in attendance with their witty quips and stunning mind-games. Even The movie’s ending perpetuates the on-going myth that the ‘night of death’ was not triggered by the failure of the Mogadishu hijack (7) to negotiate their release but was in fact a pre-arranged multiple state murder made to look like simultaneous suicide. The movie culminating in a defiant cadre of young stern faced acolytes holding a graveside vigil, determined eyes set on continuing the struggle.

As a consequence, Christina Gerhardt writing in the Film Quarterly describes the movie thus: ‘During its 150 minutes, the film achieves action film momentum, bombs exploding, bullets spraying and glass shattering’. While Christopher Hitchens commenting in Vanity Fair refers to the movie’s ‘Uneasy relationship between sexuality and cruelty . . . an almost neurotic need to oppose authority’. A theme implied by Michael Bubach, son of Siegfried Bubach, the former Chief Federal prosecutor assassinated by the Red Army Faction in 1977, who’s summation of the feature pointed to the fact that the film ‘concentrates almost exclusively on portraying the perpetrators, which carries the danger that the viewer will identify too strongly with the protagonists’.

Examples of how this claim can be justified are so numerous that they would prove tedious to list. However, two personifications, beyond the central characters, stand out in particular, the first involving a chase sequence where Petra Schelm, portrayed by the beautiful Alexandra Maria Lara, is cornered and dies defiantly in a shoot-out with a horde of drone-like cops. The second is the murderous Brigitte Mohnhaupt, depicted by the stunning Naja Uhl, who is shown bedding Peter-Jurgen Boock, played by the teenage heart-throb actor Vinzenz Kiefer, before cold bloodedly slaughtering Siegried Bubach in his own home, organizing the ‘hit’ on Jurgen Ponto, Chairman of the Dresdner Bank of Directors, and the kidnap and murder of Hanns Martin Schleyer. Mohnhaupt, the leader of the second generation of the urban guerillas was also implicated in the 1981 attempt to kill NATO General Frederick Kroesen with a PRG-7 anti-tank missile. In fact, just the sort of unrepentant femme fatale we meet in her polar-opposite, the rightist Francesca Mambro in A Student Named Alexander, but who is treated in the diametrically opposite way.

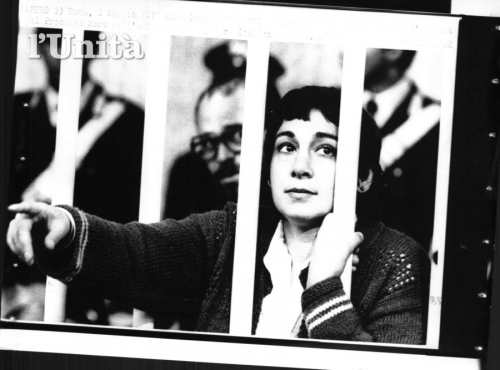

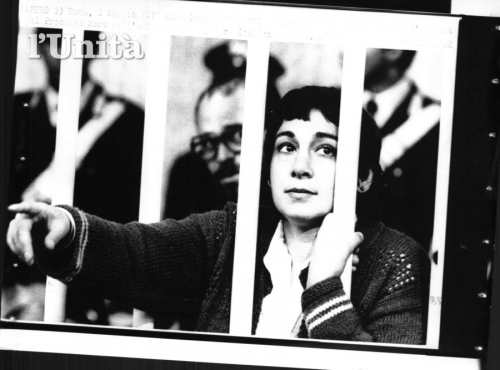

In Enzo De Camillis’s 15 minute silver ribbon winning short, shown at the Roma Film Fest and lauded for its journalistic quality, the much maligned Mambro is portrayed by Valentina Carnelutti (8), who at least partially resembles Mambro. De Camillis, a blood relative of the Alexander in question, (so no conflict of interest there?) indicated his intent in making the movie was to ‘show young people what they do not know, to reflect on a period of history that should not be repeated’. So, following a showing at The House of Cinema to an audience of impressionable students, a discussion is initiated, moderated by Santo Della Volpe (9), who declares at the outset, that ‘The goal of the short is not to re-open old wounds or discussions on the years of lead (10), but to bring to light the issue of the victims that are set aside, of which we no longer speak’.

Really? Well, that is somewhat convenient given the long list of crimes committed by the Italian Brigate Rosse during the period in question. The most notorious being the ambush at Via Fani on the 16th March 1978 and the kidnap and murder of the President of the Christian Democrats, Aldo Moro. But it should also be remembered, especially given the context of De Camillis’s film, that the Left also killed activists from the right wing Italian Social Movement (MSI) and the University National Action group, like Miki Mantakas, murdered in Via Ottaviano in Rome in 1975, and Stephan and Virgilio Mattei, the sons of the MSI party District Secretary for Prati.

It is also a disingenuous claim given the vociferous presence of the Association of Families of victims of the massacre at Bologna train station of 2nd August 1980, whose demands echo down the decades through documentaries and dramas. The latter being the main event used to demonize Mambro and her then lover, now husband, Valerio Fioravanti (11). Although, they have long denied involvement in the Bologna attack, though freely admitting, like their Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari (Armed Revolutionary Nuclei) NAR accomplices to other political killings, such as, the assassination of Judge Vittorio Occorsio (12) in 1976 and Magistrate Mario Amato (13) in 1980.

Fioravanti maintains that the bombing was the work of Libya, but the Italian government were reluctant to pursue that line of enquiry because of the state’s dependence on Libya’s oil and blamed neo-fascists instead. Mambro and Fioravanti also confessed to planning an attack on the then Prime Minister Francesco Cossiga (14), so one can hardly accuse them of hiding their intentions. When the initial 16 year prison term for Mambro was converted into house arrest in 1998, the Bologna Association’s President Paolo Bolognesi, described Mambro’s parole as ‘A disgrace. It is outrageous that this parole was granted to a terrorist who does not have the requirements, who was sentenced and has never expressed any feelings of detachment from her past’. This, despite the fact that the NAR, never claimed responsibility for the incident and there is substantive cause to believe that the Mafia Banda della Magliana gang (15) and prominent politician Licio Gelli’s (16) secretive Masonic Propaganda Due P2 Lodge (17) linked to the NATO’s Cold-War Operation Gladio architecture (18) had a hand in the incident.

The prosecution’s main witness against Mambro’s partner Fioravanti, Massimo Sparti, of the banda della Magliana, was even contradicted by his own son. ‘My father has lied about his part in the Bologna history’, he declared. Similarly the sinister presence of German terrorists Thomas Kram and Margot Frohlich, closely linked to both the PLO and Carlos the Jackal, who were in Bologna that very same day was never properly investigated. Coincidences like this and the possible link to the Ustica Massacre (19), when Aerolinea Itavia flight 870 was brought down by a missile, gave President Francesco Cossiga pause for thought, leading him to state on the 15th March 1991 that he felt the attribution of the Bologna Massacre to fascist activists may be based on misinformation supplied by the security services.

Returning to A Student named Alexander, unlike the Baader Meinhof Complex, the detail is nearly entirely on the victim, showing his cluttered bedroom, his journey by car to the art school in Piazza Risorgimento. No context is provided as to why Mambro and the NAR are robbing the Banca Nazionale on the 5th March 1982. Neither is reference made to the murder of her fellow MSI activists Franco Bigonzetti and Francesco Ciavatta, gunned down in the Acca Larentia by Left extremists, the Armed Squads for Contropotere Territorial, despite the fact that this led Mambro and her cohort to confront both their political opponents and the police in three days of shootings, stabbings and torching cars across Prenestino:

‘A few of us knew what this meant. Francesco Ciavatta was in our small circle. Our immediate reaction was shock, as if a relative had died. We looked at each other not knowing what to do. All around the city young militants flocked to us. The Italian Social Movement did not react. Kids like us were being used to keep order at meetings of Giorgi Almirante (20) , ready to take the blows and hit back . . . Acca Larentia marked the final break with the MSI . . . It could no longer be our home. For three days we shot at police and this marked the point of no return . . .’

— Francesca Mambro

Even, the circumstances of Alexander’s death are disputed. The movie depicts Mambro standing over the boy, firing into his head execution style, apparently mistaking him and his small umbrella for an armed plain clothes policeman. The counter argument is that he was killed in cross-fire as the NAR broke out of a police encirclement. A shoot out in which Mambro did not have in her possession the gun that was identified as the murder weapon and was herself very seriously wounded in the abdomen. She later recalls, hiding out in a garage, where a young doctor visits her and confirms ‘that it is only a matter of time . . . saying I could die . . .’

A discussion followed as to whether or not her compatriots should kill her there and then because she may talk under anesthetic but instead the NAR cell, led by Giorgio Vale (21), who went on later to found Terza Posizione (22), deposited her on the roadside outside an Emergency room.

When Mambro’s Rome based lawyer Amber Giovene challenged the authenticity of the way Mambro is depicted in the movie, claiming it ‘harmed her image’ she was met with a barrage of criticism. The case, overseen by prosecutor Barbara Sargent, was opened three months after the film opened and came like a bolt from the blue to the self-righteous director and the cultural association School of Arts and Entertainment. People in Bologna were whipped up into a state of frenzy, signing a petition in support of the film, which had already received a letter of commendation from the President of the Republic, Giorgio Napolitano. Expressions like censorship and statements like ‘You cannot stop a cultural work, you cannot stop history’, were bandied around with the usual air of moral indignation.

The 2013 Appeal notes relating to the accusation of defamation of Mambro’s character read: due to the benefit of the law, Francesca Mambro, who has never repented of her criminal and terrorist past, nor as ever wanted to work together to build the truth about serious events like the Bologna Massacre, will remain free. The request for the seizure of the short film is extremely serious because it sets a precedent on the freedom of cultural expression, journalism and news, and also because it opens the door to dangerous revisions and attempts to wipe clean historical memory’. The account continues: ‘A country without memory will never understand the present or the future’.

The double standards and contradictions exemplified in the differing responses to A Student Called Alexander and The Baader Meinhof Complex cannot be more stark. Memorialization of such actions are to be glamorized and mythologized if of the Left and censored and misrepresented if of the Right. The word revision is of itself loaded, implying an attempt to challenge supposedly known historical facts and is a term usually reserved for historians deviating from the legend of the Jewish Holocaust. Indeed, it seems that anything that transgresses the Left’s self-serving narrative is to be expunged, cast down the Orwellian memory hole, or twisted beyond all recognition.

Roberto Natale, the auteur of such movie classics as Kill Baby Kill and Terror Creatures from the Grave, also reiterated before his recent demise, that ‘there is a right and duty to tell. Art strengthens the record and citizens need to know. We journalists are on the side of those who stubbornly continue to speak against the custom in our country to silence uncomfortable voices, instead of being willing to speak. This short film has to circulate and be seen in schools, but not only in Rome’.

So, is the movie meant to educate or perpetuate the questionable conviction of Mambro for that specific crime? Be re-assured De Camillis states: ‘I tell you a story, I do not give you a political speech. I want to get out of games of this type. The short film I made for a number of reasons that I think are important. It is a warning to our politicians. Right now, if you do not listen to the needs of young people, you risk terrorism, perhaps we have already. We remember the riots in San Giovanni in Rome in October (23), the bullets that came in envelopes and the letter bombs’.

Then specifically commenting on the release of Francesca Mambro, but of course not being invested in any way, De Camillis adds:

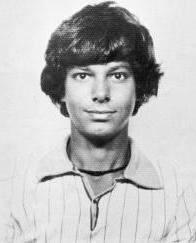

I will not even enter into legal issues because one relies on the judgment of the judiciary already formulated in 1985. But a citizen reflecting on the penalties imposed on others for far less serious offenses fully expatiated are still in prison. Mambro was guilty of 97 murders and was sentenced to nine life sentences. Yet, she walks outside, lives 400 meters from my house, and I may happen across her path by accident. There is a whisper that this story has resurfaced because of my family bonding and friendship with Alexander . . . Who was Alexander Caravillani? He was a boy of 17, he ran with the times, had a girlfriend, and harbored all the fantasies of a 17-year-old. He was not political, nor left or right. He passed in front of the bank, was simply crossing the street, going to school when he was shot, his short umbrella tumbling from his jacket, leading Mambro to believe he was a plain clothes policeman. Then she came back and put a bullet in his head. For that, she was sentenced to life imprisonment.

This is a story, he insists once again, to preserve the history of the years of lead.

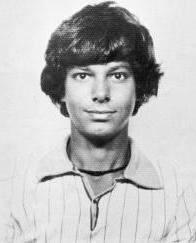

And if that is indeed the case, why not tell the story of one of the murdered MSI Youth Front members, Sergio Ramelli, 18; Francesco Cechin, 19; and Paolo Di Nella, 20, contemporaries of Alexander Caravillani (picture) and Mambro, who met their deaths by beating, shooting, and stabbings from Leftist brigands like the Autonomus Workers in the late ’70s and early ’80s? But of course, that will never happen. It does fit their agenda.

And if that is indeed the case, why not tell the story of one of the murdered MSI Youth Front members, Sergio Ramelli, 18; Francesco Cechin, 19; and Paolo Di Nella, 20, contemporaries of Alexander Caravillani (picture) and Mambro, who met their deaths by beating, shooting, and stabbings from Leftist brigands like the Autonomus Workers in the late ’70s and early ’80s? But of course, that will never happen. It does fit their agenda.

On February 11th 2012, De Camillis in direct contradiction to his supposed non-political stance is quoted, ‘Today, the city of Rome is right’, referring to the ‘post fascist’ Mayor Gianni Alemanno (24), MSI Youth Front veteran and graduate of Campo Hobbit (25), who was elected in April 2008 to the sound of Fascist-era songs and shouts of ‘Duce’. ‘Who are those who have called me to present the short film?’ asked Camillis, ‘They are Alemanno’s allies, Berlusconi’s Il Popolo della Liberta (26) . . . When it all came out I was in silence and I decided to just promote it, as I always do. But in the face of this attack, I mean to defend it at all costs. It is a ‘cultural action’ like opposition to gagging journalists. This is a way to silence not only the news but also the authorship of the image’.

There is clearly no intention of admitting even the possibility of bias or inaccuracy. De Camillis and his people are intent on staking their claim to the moral high ground. The following day, Mambro’s lawyer responded: ‘I write in the name and on behalf of the my client Francesca Mambro about the article published yesterday . . . I understand the presentation of the short film flatters the author. But I do not understand the claim that Mambro came back and shot him in the head. I do not know if Mr. De Camillis’s draws from insider sources? Caravillani, unfortunately died in the firefight because a bouncing bullet caused his immediate death. A bullet from an assault rifle that Mambro had never had in her possession, either as she entered the bank or as the NAR shot their way out. The scene is constructed in a way that will definitively condemn Mambro’. When Caravillani was struck, the judges concluded, it was because the young man, after he had run, suddenly found himself in the trajectory of shots fired between the various agents . . . Unfortunately, even the trailers of the short graphically depict Mambro in the disputed manner, astride a guy lying on the ground, shooting the coup de grace . . . I am sure, that in the name of the need to preserve the memory of the years of lead, both you and the newspaper for which he writes would give an account of this correction’. My personal advice is not to hold your breath for a retraction. Smear and distortion is their modus operandi.

Sentenced, for the killing of 9 individuals between May 1980 and March 1982, and the alleged involvement in the massacre of the Bologna bombing on 2nd August 1980, Mambro served 16 years in prison. Sometimes sharing a cell with Anna Laura Braghetti (27) (picture), of the Brigate Rosse, then after 1998 home detention until the 16th September 2008 when she was granted parole on the basis of ‘repeated and tireless dedication to reconciliation and peace with the victims’ families (28). Parole was ended on September 16th 2013 when the sentence was disposed of . . .’

So to end has I began with a quote from a French man of letters, Alexandre Dumas (29), author of The Three Musketeers, ‘she is purely animal; she is the babooness of the Land of Nod; she is the female of Cain: Slay her!’ Or at least besmirch her reputation and disparage her cause so that no one will want to emulate her.

Notes

1. Along with Edgar Allan Poe, Baudelaire identified counter enlightenment philosopher Joseph de Maistre as his maître a penser and adopted aristocratic views. He argued ‘There are but three things worthy of respect: the priest, the warrior and the poet. To know, to kill and to create . . .’

2. Auguste Clesinger (1814-1883), French sculptor who created Bacchante, the Infant Hercules Strangling Snakes, Nereid, and Sappho, was an Officier de la Legion d’honneur.

3. Rudi Dutschke (1940-1979), disciple of Rosa Luxemburg and critical Marxist, survived Josef Bachmann’s attack, but drowned as consequence of having an epileptic fit in the bath.

4. Holger Meins, seized with Baader and Jan Carle-Raspe on the 1st June 1972, went on hunger strike, dying a mere 39kg in weight. He is a central character in the movie Moses und Aron by Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet (1974). Followed by a documentary about Meins called Starbuck — Holger Meins by Gerd Conradt (2002).

5. Bobby Sands (1954-81), a member of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) died whilst on hunger strike in HM Maze Prison. During the course of his protest he was elected to the British Parliament as an Anti-H Block candidate. He has been depicted in various films including Some Mother’s Son (1996) and Hunger (2008) and is celebrated in songs like Christy Moore’s The People’s Own MP’.

6. Stammheim is a high security prison in Stuttgart.

7. Four militants of the Commando Martyr Halime hijacked Lufthansa flight 181 on the 13th October 1977. The plane was stormed in Somalia by GSG-9 elite counter-terrorism units in an operation code-named Feuerzauber (Fire Magic).

8. Valentina Carnelutti was trained at the Theatre Active in Rome and the Mime Theatre Movement. She has also appeared in the movies Martina Singapore (1995), Ridley Scott’s Hannibal (2001) and The Best of Youth (2003).

9. Santo Della Volpe is a professional journalist who covered the first Gulf War and is a managing editor on Italy’s TG3.

10. The term “Years of Lead” was used to describe the socio-political turmoil in Italy between the 1960s to the 1980s. It is thought that the reference originated from a movie called Marianne and Julianne by Margarethe Von Trotta. The Italian title was Anni di Piombo, literally years of lead. A later linked feature called The German Sisters (1981) became a classic of new German cinema, sympathetic to Gudrun Ensslin and dedicated to women’s civil rights.

11. Born in 1958, Giuseppe Valerio ‘Giusva’ Fioravanti, was a former child actor, who became a leader in the NAR and has been romantically linked with Mambro since 1979. While serving his prison sentence he made a documentary on Rome’s Rebibbia prison, Piccoli Ergastoli, Little Life Sentences (1997).

12. Occorsio Vittorio (1929-1976) oversaw the trial of those indicted for the Piazza Fontana bombing.

13. Maria Amato was an Italian magistrate assassinated by NAR member Gilberto Cavallini in 1980.

14. Francesco Cossiga, Italy’s 42nd Prime Minister and 8th President between 1985-1992.

15. The Banda della Magliana was a criminal network operating out of Lazio, named after the district from where most of their leaders originated. Their activities included the murder of the banker Roberto Calvi, the kidnapping of Emanuela Orlandi and the attack on John-Paul II.

16. Licio Gelli, an Italian financier, heavily involved in the Banco Ambrosiano scandal and the venerable master of the P2 Lodge.

17. The Propaganda Due (P2) Lodge was under the jurisdiction of the Grand Orient of Italy implicated in numerous crimes and mysteries, often referred to as a ‘state within the state’.

18. Operation Gladio was the code-name for NATO’s ‘stay behind’ activity should the Warsaw Pact mount an invasion of western Europe. The name Gladio came from the word gladius, a type of short Roman sword.

19. The Ustica Massacre is still a subject of some controversy. Whether or not a French naval aircraft brought the plane down with a missile, or a bomb was set off in the toilet as evidenced by forensic experts, it is known that the Libyan leader Colonel Gadaffi was in the same airspace at the time. Linking the Ustica and Bologna incidents became common in some conspiracy circles.

20. Giorgio Almirante (1914-1988) studied under Giovanni Gentile, the eminent pro-Fascist philosopher and wrote for the Rome-based fascist journal Il Tevere. He once described Julius Evola as ‘Our Marcuse, only better’. Almirante was suspected of safe-housing Carlo Cicuttini, a MSI leader in the Monfalcone area and later a member of the Ordine Nuovo, a suspect convicted in absentia for his part in the Peteano di Sagrado killings. Almirante and his rival Pino Rauti often clashed bitterly on the tactics and methodology used by the Italian Right.

21. Giorgi Vale was killed in a shoot-out with police.

22. The Terza Posizione emerged from the national student’s movement under Roberto Nistri, who was imprisoned from 1982 to the early 2000s.

23. The San Giovanni Riots of the 15th October were violent street protests by Black Bloc Left extremists.

24. Gianni Alemanno was born in Bari in 1958. He is a former secretary of the MSI’s Youth Wing, who entered the Chamber of Deputies representing Lazio, serving as Rome’s 63rd Mayor between 2008-2013 and a Minister of Agriculture under Silvio Berlusconi. He is married to Isabella Rauti, the daughter of Pino Rauti.

25. Campo Hobbit was named after Catholic writer J. R. R. Tolkien’s first novel. It was an alternative cultural and musical ‘happening’ linked to Elemire Zolla who wrote The Arcana of Power 1960-2000. Held in various locations, the first in Montesarchio, it boasted its own Manifesto and became a ‘field school’ for the Italian New Right and thinkers like Pino Rauti and Marco Tarchi.

26. Berlusconi’s Il Poplo della Liberta was closely aligned with Gianfranco Fini’s conservative National Alliance and Umberto Bossi’s Lega Nord.

27. Anna Laura Braghetti owned the apartment where Aldo Moro was imprisoned. She is also the subject of her own book Prisoner which influenced Marco Bellocchio’s film Good Morning, Night (2003).

28. Mambro currently works for the Italian NGO Hands off Cain, an association campaigning against the death penalty linked to the Libertarian Radical Party.

29. Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870). It was said of Dumas, that his ‘tongue was like a windmill — once set in motion, you never knew when it would stop, especially if the theme was himself’ — Watts Phillips, English illustrator, playwright and novelist.

Related

Lucie est une jeune Parisienne, fille d’un père aux convictions païennes et d’une mère chrétienne d’origine ukrainienne. Spécialiste des parfums, elle doit se rendre dans un pays oriental (dont le nom ne sera, à dessein, jamais indiqué) pour mener une recherche dans le cadre de son sujet d’étude, à savoir « l’histoire des odeurs et la mémoire des peuples ». Le thème des parfums reviendra d’ailleurs comme un leitmotiv tout au long du film, qui aurait tout à fait pu être une œuvre tournée en odorama ! Les choses ne se passent toutefois pas comme prévu et, peu après son arrivée, la jeune fille, trompée par un chauffeur de taxi, est livrée à un groupe de djihadistes qui la prennent en otage pour obtenir de l’argent de la France. L’histoire nous est racontée tour à tour selon trois perspectives : celle de Lucie, celle de Younes (le chauffeur de taxi en proie à un dilemme moral et que les difficultés économiques contraignent à se faire le complice des islamistes) et celle d’Abou (un djihadiste d’origine française qui va peu à peu être assailli de doutes sur son engagement à mesure que la situation se dégrade).

Lucie est une jeune Parisienne, fille d’un père aux convictions païennes et d’une mère chrétienne d’origine ukrainienne. Spécialiste des parfums, elle doit se rendre dans un pays oriental (dont le nom ne sera, à dessein, jamais indiqué) pour mener une recherche dans le cadre de son sujet d’étude, à savoir « l’histoire des odeurs et la mémoire des peuples ». Le thème des parfums reviendra d’ailleurs comme un leitmotiv tout au long du film, qui aurait tout à fait pu être une œuvre tournée en odorama ! Les choses ne se passent toutefois pas comme prévu et, peu après son arrivée, la jeune fille, trompée par un chauffeur de taxi, est livrée à un groupe de djihadistes qui la prennent en otage pour obtenir de l’argent de la France. L’histoire nous est racontée tour à tour selon trois perspectives : celle de Lucie, celle de Younes (le chauffeur de taxi en proie à un dilemme moral et que les difficultés économiques contraignent à se faire le complice des islamistes) et celle d’Abou (un djihadiste d’origine française qui va peu à peu être assailli de doutes sur son engagement à mesure que la situation se dégrade).

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

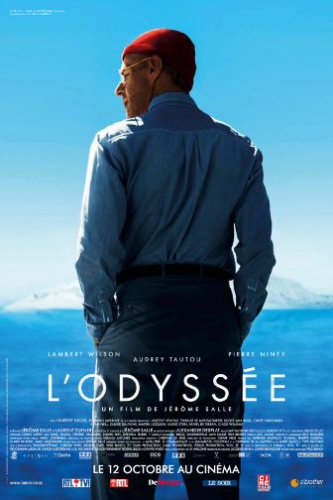

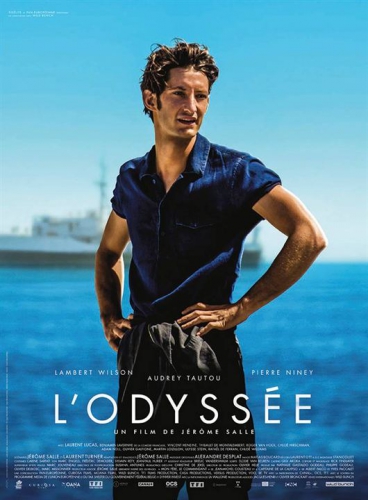

Digg Autour de la figure de Jacques-Yves Cousteau, interprété par Lambert Wilson, L'Odyssée, film de Jérôme Salle, César du meilleur premier film pour Anthony Zimmer, nous entraîne dans trente années qui vont forger un mythe en même temps que changer le monde : 1949-1979. Deux mondes que toute oppose. Derrière l'Odyssée, nous assistons plutôt à une série d'odyssées, celle de la famille Cousteau, celle de la France triomphante des Trente Glorieuses, celle, au final, de l'écologie balbutiante.

Autour de la figure de Jacques-Yves Cousteau, interprété par Lambert Wilson, L'Odyssée, film de Jérôme Salle, César du meilleur premier film pour Anthony Zimmer, nous entraîne dans trente années qui vont forger un mythe en même temps que changer le monde : 1949-1979. Deux mondes que toute oppose. Derrière l'Odyssée, nous assistons plutôt à une série d'odyssées, celle de la famille Cousteau, celle de la France triomphante des Trente Glorieuses, celle, au final, de l'écologie balbutiante. Le rêve Cousteau se transforme ainsi peu à peu en cauchemar pour son équipage et son épouse, attachés à la Calypso, alors que le Commandant se rend dans les soirées mondaines à New-York ou à Paris. La décrépitude de son épouse, qui ressemble de plus en plus à une tenancière de bistrot de province, contraste avec l'allure de son mari, toujours impeccablement habillé, signant des autographes et séduisant les femmes. L'archétype de l'homme français, séducteur et agaçant qui parvient parfois à conquérir l'Amérique.

Le rêve Cousteau se transforme ainsi peu à peu en cauchemar pour son équipage et son épouse, attachés à la Calypso, alors que le Commandant se rend dans les soirées mondaines à New-York ou à Paris. La décrépitude de son épouse, qui ressemble de plus en plus à une tenancière de bistrot de province, contraste avec l'allure de son mari, toujours impeccablement habillé, signant des autographes et séduisant les femmes. L'archétype de l'homme français, séducteur et agaçant qui parvient parfois à conquérir l'Amérique.

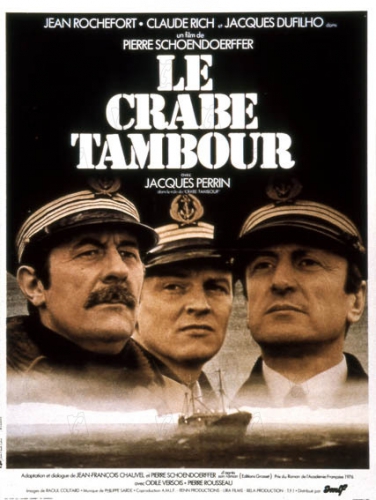

Quittant Lorient, l'escorteur d'escadres Jauréguiberry est chargé d'assister des chalutiers de pêche sur les bancs de Terre-Neuve pour sa dernière mission avant démilitarisation. Au cours de la traversée, le commandant, le médecin-capitaine et le chef mécanicien se remémorent Willsdorff, dit le Crabe-Tambour, un personnage qu'ils ont côtoyé naguère tandis qu'il participait aux guerres d'Indochine et d'Algérie. Partisan du maintien de l'Algérie française, le Crabe-Tambour avait rejoint les rangs de l'Organisation de l'Armée secrète. Préférant le légalisme à la clandestinité, le commandant avait été contraint de manquer à sa parole et rompre le contact avec le Crabe-Tambour, aujourd'hui patron de l'un des chalutiers escortés. Si proches après tant de temps. Et pourtant, les mauvaises conditions météorologiques empêchent le commandant de saluer l'ancien O.A.S. en personne. Le cancer du poumon qui condamne le commandant à une mort imminente est bien peu de choses face aux tourments de sa trahison à l'égard de Willsdorff...

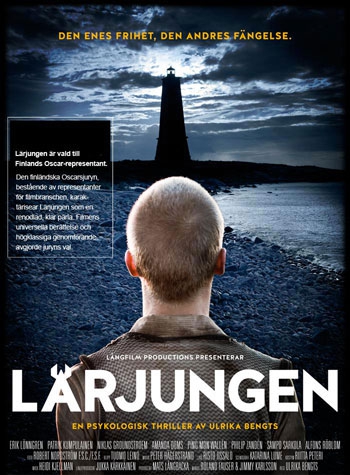

Quittant Lorient, l'escorteur d'escadres Jauréguiberry est chargé d'assister des chalutiers de pêche sur les bancs de Terre-Neuve pour sa dernière mission avant démilitarisation. Au cours de la traversée, le commandant, le médecin-capitaine et le chef mécanicien se remémorent Willsdorff, dit le Crabe-Tambour, un personnage qu'ils ont côtoyé naguère tandis qu'il participait aux guerres d'Indochine et d'Algérie. Partisan du maintien de l'Algérie française, le Crabe-Tambour avait rejoint les rangs de l'Organisation de l'Armée secrète. Préférant le légalisme à la clandestinité, le commandant avait été contraint de manquer à sa parole et rompre le contact avec le Crabe-Tambour, aujourd'hui patron de l'un des chalutiers escortés. Si proches après tant de temps. Et pourtant, les mauvaises conditions météorologiques empêchent le commandant de saluer l'ancien O.A.S. en personne. Le cancer du poumon qui condamne le commandant à une mort imminente est bien peu de choses face aux tourments de sa trahison à l'égard de Willsdorff... L'été 1939, âgé de treize ans, Karl Berg débarque sur la petite île déserte de Lågskär, perdue en pleine mer Baltique, afin d'être l'apprenti du gardien du phare, Hasselbond, accompagné de son épouse et de ses deux enfants. Jugé trop jeune, le gardien refuse son enseignement à l'apprenti, pourtant bien contraint de demeurer sur l'île, le bateau désormais reparti. Karl va s'échiner à se lier d'amitié avec Gustaf, le souffre-douleur et fils de Hasselbond. Karl se révèle entreprenant et dégourdi et est progressivement accepté du gardien-tyran, au point que ce dernier commence à favoriser l'apprenti à son propre fils. L'amitié entre les deux jeunes garçons se double bientôt d'une forte rivalité. Par-dessus tout, Hasselbond interdit tout mensonge dans son entourage. Mais lui-même ne semble pas exempt de reproches...

L'été 1939, âgé de treize ans, Karl Berg débarque sur la petite île déserte de Lågskär, perdue en pleine mer Baltique, afin d'être l'apprenti du gardien du phare, Hasselbond, accompagné de son épouse et de ses deux enfants. Jugé trop jeune, le gardien refuse son enseignement à l'apprenti, pourtant bien contraint de demeurer sur l'île, le bateau désormais reparti. Karl va s'échiner à se lier d'amitié avec Gustaf, le souffre-douleur et fils de Hasselbond. Karl se révèle entreprenant et dégourdi et est progressivement accepté du gardien-tyran, au point que ce dernier commence à favoriser l'apprenti à son propre fils. L'amitié entre les deux jeunes garçons se double bientôt d'une forte rivalité. Par-dessus tout, Hasselbond interdit tout mensonge dans son entourage. Mais lui-même ne semble pas exempt de reproches...

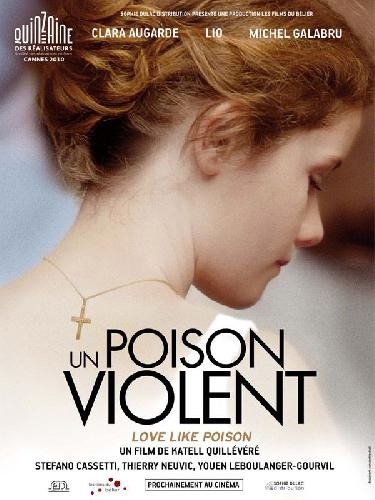

Cet été, plus rien ne sera comme avant pour Anna, quatorze ans. Fraichement rentrée de l'internat, elle découvre que son père a quitté le domicile conjugal. Sa mère, effondrée, trouve quelque réconfort auprès du jeune prêtre du village breton qui ne la rend pas insensible. Quant à Anna, la consolation, c'est son mécréant de grand-père qui la lui procure. Anna prépare pieusement sa confirmation qui constitue la prochaine étape de sa foi catholique. Mais surgit Pierre qui fait chavirer le cœur de l'adolescente. Déboussolée par ses déboires familiaux et sentimentaux, Anna se met à fréquenter les enterrements. Ses croyances religieuses sont d'autant plus ébranlées que le regard des autres sur son corps en pleine puberté change. Pierre éprouve un désir ardent pour Anna, loin d'être insensible, tandis que sa mère, succombant à la crise de la quarantaine, la jalouse. C'est au prêtre qu'il reviendra de palier l'absence du père et tentera de prodiguer ses meilleurs conseils pour qu'Anna reste dans le droit chemin...

Cet été, plus rien ne sera comme avant pour Anna, quatorze ans. Fraichement rentrée de l'internat, elle découvre que son père a quitté le domicile conjugal. Sa mère, effondrée, trouve quelque réconfort auprès du jeune prêtre du village breton qui ne la rend pas insensible. Quant à Anna, la consolation, c'est son mécréant de grand-père qui la lui procure. Anna prépare pieusement sa confirmation qui constitue la prochaine étape de sa foi catholique. Mais surgit Pierre qui fait chavirer le cœur de l'adolescente. Déboussolée par ses déboires familiaux et sentimentaux, Anna se met à fréquenter les enterrements. Ses croyances religieuses sont d'autant plus ébranlées que le regard des autres sur son corps en pleine puberté change. Pierre éprouve un désir ardent pour Anna, loin d'être insensible, tandis que sa mère, succombant à la crise de la quarantaine, la jalouse. C'est au prêtre qu'il reviendra de palier l'absence du père et tentera de prodiguer ses meilleurs conseils pour qu'Anna reste dans le droit chemin...

Paris est occupée par les armées du Reich en cette année 1943. La pénurie d'essence, sévissant en France, réduit à l'inactivité le chauffeur de taxi Marcel Martin. Le chauffeur survit en transportant clandestinement des colis destinés à l'alimentation du marché noir. L'activité n'est pas sans risque et Martin apprend que son compère vient d'être arrêté par la police. Il lui faut le remplacer au plus vite. Dans un bistrot, Martin fait la connaissance impromptue de Grandgil, qu'il prend pour un plâtrier, qui acceptera d'entreprendre la traversée de Paris. Le duo se rend chez Jambier, épicier de la rue Poliveau. L'épicier les charge de convoyer un cochon réparti dans quatre valises dans une boucherie de la rue Lepic. Six kilomètres périlleux au cours desquels toutes les péripéties peuvent se produire. A plus forte raison lorsque le nouvel acolyte Grandgil se révèle vite incontrôlable...

Paris est occupée par les armées du Reich en cette année 1943. La pénurie d'essence, sévissant en France, réduit à l'inactivité le chauffeur de taxi Marcel Martin. Le chauffeur survit en transportant clandestinement des colis destinés à l'alimentation du marché noir. L'activité n'est pas sans risque et Martin apprend que son compère vient d'être arrêté par la police. Il lui faut le remplacer au plus vite. Dans un bistrot, Martin fait la connaissance impromptue de Grandgil, qu'il prend pour un plâtrier, qui acceptera d'entreprendre la traversée de Paris. Le duo se rend chez Jambier, épicier de la rue Poliveau. L'épicier les charge de convoyer un cochon réparti dans quatre valises dans une boucherie de la rue Lepic. Six kilomètres périlleux au cours desquels toutes les péripéties peuvent se produire. A plus forte raison lorsque le nouvel acolyte Grandgil se révèle vite incontrôlable...

Cette industrie artistique a aidé à comprendre (même si elle a parfois caricaturé ou recyclé) la beauté du monde ancien, tellurique et agricole qui allait disparaître. Le cinéma japonais est magnifique dans ce sens jusqu’au début des années soixante. Et donc l’objet de ce livre est de pousser la jeunesse à redécouvrir l’esprit de la Genèse, la nature, les animaux, les cycles, les hauts faits, les voyages et les grandes aventures initiatiques. Les romains, dit déjà Juvénal dans ses Satires, connurent le même problème, les enfants ne croyant même plus aux enfers ! C’est un livre sur la poésie de la vie et des images qui nous aident à l’affronter aux temps de l’existence zombie et postmoderne.

Cette industrie artistique a aidé à comprendre (même si elle a parfois caricaturé ou recyclé) la beauté du monde ancien, tellurique et agricole qui allait disparaître. Le cinéma japonais est magnifique dans ce sens jusqu’au début des années soixante. Et donc l’objet de ce livre est de pousser la jeunesse à redécouvrir l’esprit de la Genèse, la nature, les animaux, les cycles, les hauts faits, les voyages et les grandes aventures initiatiques. Les romains, dit déjà Juvénal dans ses Satires, connurent le même problème, les enfants ne croyant même plus aux enfers ! C’est un livre sur la poésie de la vie et des images qui nous aident à l’affronter aux temps de l’existence zombie et postmoderne.

En 1919, la lutte pour l'indépendance de l'Irlande vient de débuter. Les sombres Black and Tans poursuivent inlassablement les rebelles indépendantistes. Le petit village de Clonmore est l'un des théâtres d'opération. Volontaire républicain, Denis O'Hara apprend au cours de la descente que la police investira le lieu d'une réunion secrète, qui doit se tenir non loin de Dublin, afin de discuter des actions à mener. Afin de déjouer l'arrestation de chacun, O'Hara tente de prévenir ses camarades mais est touché par une balle etbbientôt appréhendé. Son arrestation le fait échouer dans sa tentative. O'Hara est emprisonné à Kildare. Sans nouvelle du jeune homme, la famille du prisonnier le croit mort. Sa mère perd la vue sous le choc de la nouvelle tandis que sa fiancée Moira est enlevée par Gilbert Beecher, traitre acquis aux loyalistes. Le jeune O'Hara parvient néanmoins à s'échapper et regagner son village...

En 1919, la lutte pour l'indépendance de l'Irlande vient de débuter. Les sombres Black and Tans poursuivent inlassablement les rebelles indépendantistes. Le petit village de Clonmore est l'un des théâtres d'opération. Volontaire républicain, Denis O'Hara apprend au cours de la descente que la police investira le lieu d'une réunion secrète, qui doit se tenir non loin de Dublin, afin de discuter des actions à mener. Afin de déjouer l'arrestation de chacun, O'Hara tente de prévenir ses camarades mais est touché par une balle etbbientôt appréhendé. Son arrestation le fait échouer dans sa tentative. O'Hara est emprisonné à Kildare. Sans nouvelle du jeune homme, la famille du prisonnier le croit mort. Sa mère perd la vue sous le choc de la nouvelle tandis que sa fiancée Moira est enlevée par Gilbert Beecher, traitre acquis aux loyalistes. Le jeune O'Hara parvient néanmoins à s'échapper et regagner son village... Dublin en 1903, Michael O'Brien est capturé. L'activiste indépendantiste est suspecté d'un attentat meurtrier sur des policiers de Sa Majesté. La justice condamne le jeune O'Brien à mort après une parodie de procès. Pendant sa détention, sa fiancée enceinte Maeve Fleming le visite en prison et obtient l'autorisation de l'épouser avant qu'il ne soit pendu. O'Brien lui remet une croix d'argent qu'arborent les nationalistes irlandais et sur laquelle sont gravés les mots "Ma vie" et "Irlande". Puisse cette croix revenir un jour au fils qu'O'Brien ne verra jamais... 1921, O'Brien n'aura effectivement jamais connu son fils qui passe cette année-là son baccalauréat dans un collège anglais. Sa condition de fils d'un rebelle lui a imposé une éducation spécifique par l'occupant sous la férule de Sir George Baverly qui veut en faire un parfait Britannique. Ainsi sont éduqués les mauvais Irlandais comme Michael Jr. Il se peut qu'il en faille plus qu'un conditionnement sous haute surveillance pour transformer un fils de rebelle en fidèle sujet de la Couronne...

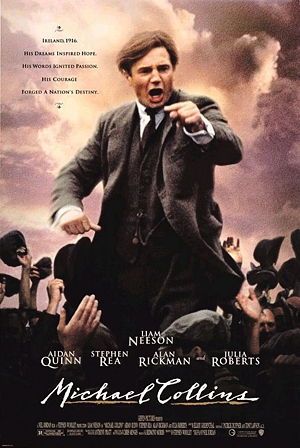

Dublin en 1903, Michael O'Brien est capturé. L'activiste indépendantiste est suspecté d'un attentat meurtrier sur des policiers de Sa Majesté. La justice condamne le jeune O'Brien à mort après une parodie de procès. Pendant sa détention, sa fiancée enceinte Maeve Fleming le visite en prison et obtient l'autorisation de l'épouser avant qu'il ne soit pendu. O'Brien lui remet une croix d'argent qu'arborent les nationalistes irlandais et sur laquelle sont gravés les mots "Ma vie" et "Irlande". Puisse cette croix revenir un jour au fils qu'O'Brien ne verra jamais... 1921, O'Brien n'aura effectivement jamais connu son fils qui passe cette année-là son baccalauréat dans un collège anglais. Sa condition de fils d'un rebelle lui a imposé une éducation spécifique par l'occupant sous la férule de Sir George Baverly qui veut en faire un parfait Britannique. Ainsi sont éduqués les mauvais Irlandais comme Michael Jr. Il se peut qu'il en faille plus qu'un conditionnement sous haute surveillance pour transformer un fils de rebelle en fidèle sujet de la Couronne... Pâques 1916, l'atmosphère est lourde dans la cité dublinoise. Chacun sent bien que des événements vont se produire. Si la rébellion d'une poignée d'insoumis irlandais éclate bien, l'issue des combats ne laisse aucun doute tant la supériorité technique des troupes anglaises est remarquable. Nombre de patriotes irlandais sont tués dans les combats. Beaucoup d'autres sont arrêtés, tel Eamon De Valera, président du Sinn Fein. On fusille des prisonniers parmi lesquels le révolutionnaire national-syndicaliste Connolly. L'insurrection est noyée dans le sang et provoque une détermination infaillible chez les survivants. Parmi les jeunes insurgés à avoir échappé à la mort, Michael Collins se jure que 1916 constituera le dernier échec des indépendantistes. Face à un ennemi supérieur en armes, la surprise doit-elle prévaloir. Aussi, la priorité est-elle l'élimination des espions. Avec l'aide de son fidèle ami Harry Boland et l'appui d'un informateur anglais, Collins devient le héraut républicain, entreprend la neutralisation des traitres et prépare une véritable stratégie de harcèlement militaire qui porte ses fruits. Le traité de 1921 accorde l'indépendance à la majeure partie de l'île. L'Ulster reste sous domination britannique, faisant se déchirer la famille républicaine...

Pâques 1916, l'atmosphère est lourde dans la cité dublinoise. Chacun sent bien que des événements vont se produire. Si la rébellion d'une poignée d'insoumis irlandais éclate bien, l'issue des combats ne laisse aucun doute tant la supériorité technique des troupes anglaises est remarquable. Nombre de patriotes irlandais sont tués dans les combats. Beaucoup d'autres sont arrêtés, tel Eamon De Valera, président du Sinn Fein. On fusille des prisonniers parmi lesquels le révolutionnaire national-syndicaliste Connolly. L'insurrection est noyée dans le sang et provoque une détermination infaillible chez les survivants. Parmi les jeunes insurgés à avoir échappé à la mort, Michael Collins se jure que 1916 constituera le dernier échec des indépendantistes. Face à un ennemi supérieur en armes, la surprise doit-elle prévaloir. Aussi, la priorité est-elle l'élimination des espions. Avec l'aide de son fidèle ami Harry Boland et l'appui d'un informateur anglais, Collins devient le héraut républicain, entreprend la neutralisation des traitres et prépare une véritable stratégie de harcèlement militaire qui porte ses fruits. Le traité de 1921 accorde l'indépendance à la majeure partie de l'île. L'Ulster reste sous domination britannique, faisant se déchirer la famille républicaine...

Pâques 1916 en Irlande. Les troubles agitent Dublin. L'insurrection..., Nora Clitheroe aimerait s'en tenir la plus éloignée possible. Mais voilà..., son époux Jack vient d'être nommé par le général Connolly commandant d'une unité. L'époux doit prendre immédiatement ses fonctions. Les dirigeants du Sinn Fein viennent de proclamer l'indépendance. Une indicible peur envahit l'épouse lorsqu'elle apprend que l'homme qu'elle aime éperdument reçoit l'ordre d'investir le bâtiment des Postes. Les rebelles possèdent l'avantage de la surprise et se battent vaillamment. Mais les nombreuses forces loyalistes écrasent sans difficultés la hardiesse des volontaires irlandais. Poursuivi sur les toits de la cité, Jack peine à retrouver Nora tout en continuant de tirer ses cartouches. Son amour pour Nora ne le fera guère abandonner la lutte armée...

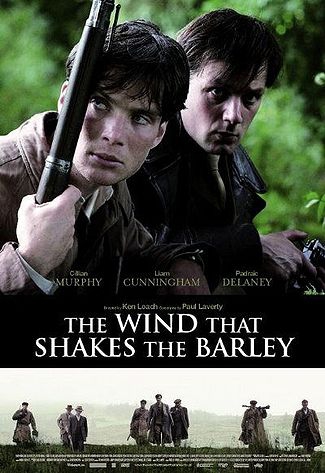

Pâques 1916 en Irlande. Les troubles agitent Dublin. L'insurrection..., Nora Clitheroe aimerait s'en tenir la plus éloignée possible. Mais voilà..., son époux Jack vient d'être nommé par le général Connolly commandant d'une unité. L'époux doit prendre immédiatement ses fonctions. Les dirigeants du Sinn Fein viennent de proclamer l'indépendance. Une indicible peur envahit l'épouse lorsqu'elle apprend que l'homme qu'elle aime éperdument reçoit l'ordre d'investir le bâtiment des Postes. Les rebelles possèdent l'avantage de la surprise et se battent vaillamment. Mais les nombreuses forces loyalistes écrasent sans difficultés la hardiesse des volontaires irlandais. Poursuivi sur les toits de la cité, Jack peine à retrouver Nora tout en continuant de tirer ses cartouches. Son amour pour Nora ne le fera guère abandonner la lutte armée... Les années 1920 en Irlande. Des bateaux entiers déversent leur flot de Black and Tans pour mâter les rebelles qui poursuivent la lutte pour l'indépendance après l'échec de l'insurrection de Pâques 1916. Les exactions sont nombreuses et la répression britannique impitoyable. A l'issue d'un match de hurling dans le comté de Cork, Damien O'Donovan voit son ami Micheál Ó Súilleabháin sommairement exécuté sous ses yeux. Malgré quelques hésitations, Damien plaque la jeune carrière de médecin qu'il devait débuter dans l'un des plus prestigieux hôpitaux londoniens pour rejoindre son frère Teddy, commandant de la brigade locale de l'I.R.A. Dans tous les comtés, des paysans rejoignent les rangs des volontaires républicains et bouter l'Anglais hors de l'île. Au prix de leur sang, et d'indicibles tourments, les volontaires de l'I.R.A. changeront le cours de l'Histoire...

Les années 1920 en Irlande. Des bateaux entiers déversent leur flot de Black and Tans pour mâter les rebelles qui poursuivent la lutte pour l'indépendance après l'échec de l'insurrection de Pâques 1916. Les exactions sont nombreuses et la répression britannique impitoyable. A l'issue d'un match de hurling dans le comté de Cork, Damien O'Donovan voit son ami Micheál Ó Súilleabháin sommairement exécuté sous ses yeux. Malgré quelques hésitations, Damien plaque la jeune carrière de médecin qu'il devait débuter dans l'un des plus prestigieux hôpitaux londoniens pour rejoindre son frère Teddy, commandant de la brigade locale de l'I.R.A. Dans tous les comtés, des paysans rejoignent les rangs des volontaires républicains et bouter l'Anglais hors de l'île. Au prix de leur sang, et d'indicibles tourments, les volontaires de l'I.R.A. changeront le cours de l'Histoire...

26 mars 1827, le grand Beethoven meurt à Vienne. Son secrétaire et homme de confiance Anton Schindler s'apprête à régler la succession du maître lorsqu'il découvre un testament annulant et remplaçant les actes précédents. Dans ce nouveau manuscrit, le musicien exprime sa volonté de léguer tous ses biens et sa fortune à son Immortelle bien-aimée. Malgré la vive opposition de la famille du compositeur, Schindler part à la recherche de la muse qui se cache derrière cette mystérieuse identité. La comtesse Giuliana Guicciardi, Joanna et la comtesse Anna Maria Erdody, chaque femme qui a partagé la vie de Beethoven évoque ses souvenirs avec le génie allemand...

26 mars 1827, le grand Beethoven meurt à Vienne. Son secrétaire et homme de confiance Anton Schindler s'apprête à régler la succession du maître lorsqu'il découvre un testament annulant et remplaçant les actes précédents. Dans ce nouveau manuscrit, le musicien exprime sa volonté de léguer tous ses biens et sa fortune à son Immortelle bien-aimée. Malgré la vive opposition de la famille du compositeur, Schindler part à la recherche de la muse qui se cache derrière cette mystérieuse identité. La comtesse Giuliana Guicciardi, Joanna et la comtesse Anna Maria Erdody, chaque femme qui a partagé la vie de Beethoven évoque ses souvenirs avec le génie allemand... 1911, Gustav Mahler rentre de voyage et regagne Vienne. Rongé par la maladie, le compositeur autrichien ignore encore qu'il ne lui reste plus que quelques jours à vivre ici-bas. Sombrant dans une profonde mélancolie, Mahler se remémore, au cours de son voyage, les étapes importantes de sa vie parfois fantasmée. De religion juive, l'enfance de Mahler s'est heurtée au fort antisémitisme de la société viennoise qui contraint une future conversion au Christianisme, seule possibilité de faciliter son ascension et la direction de l'orchestre de Vienne. Les drames familiaux ont également forgé la vie de l'apostat. La violence de son père à l'encontre de sa mère, le suicide de son frère et la mort prématurée de la fille qu'il eut avec Alma, son épouse, sont autant d'évènements qui constituent de douloureuses cicatrices...

1911, Gustav Mahler rentre de voyage et regagne Vienne. Rongé par la maladie, le compositeur autrichien ignore encore qu'il ne lui reste plus que quelques jours à vivre ici-bas. Sombrant dans une profonde mélancolie, Mahler se remémore, au cours de son voyage, les étapes importantes de sa vie parfois fantasmée. De religion juive, l'enfance de Mahler s'est heurtée au fort antisémitisme de la société viennoise qui contraint une future conversion au Christianisme, seule possibilité de faciliter son ascension et la direction de l'orchestre de Vienne. Les drames familiaux ont également forgé la vie de l'apostat. La violence de son père à l'encontre de sa mère, le suicide de son frère et la mort prématurée de la fille qu'il eut avec Alma, son épouse, sont autant d'évènements qui constituent de douloureuses cicatrices...

L'année 1801, Beethoven tombe fou amoureux à Vienne d'une jeune et jolie italienne, la comtesse Guicciardi qui compte parmi ses élèves attentives. La comtesse deviendra sa muse bien qu'elle ne ressen pour lui qu'une grande amitié, empreinte d'une forte admiration. L'élève italienne annonce son vœu de mariage avec le comte Gallenberg. Profondément meurtri, le compositeur s'enfuit tandis que l'orage se déchaîne. Lé génie se rend compte que la surdité le gagne. Thérèse de Brunswick, cousine de la comtesse, prend bientôt la place de Giulietadans le cœur éploré de Beethoven. Sans aucune concertation machiavélique, Giulieta se rend compte de l'échec inévitable de son mariage et entreprend de se rapprocher de son mentor tandis que Thérèse devine la nature inextinguible des sentiments de Beethoven envers la comtesse. Thérèse aussi ne demeurera qu'une amie et Beethoven un génie solitaire...

L'année 1801, Beethoven tombe fou amoureux à Vienne d'une jeune et jolie italienne, la comtesse Guicciardi qui compte parmi ses élèves attentives. La comtesse deviendra sa muse bien qu'elle ne ressen pour lui qu'une grande amitié, empreinte d'une forte admiration. L'élève italienne annonce son vœu de mariage avec le comte Gallenberg. Profondément meurtri, le compositeur s'enfuit tandis que l'orage se déchaîne. Lé génie se rend compte que la surdité le gagne. Thérèse de Brunswick, cousine de la comtesse, prend bientôt la place de Giulietadans le cœur éploré de Beethoven. Sans aucune concertation machiavélique, Giulieta se rend compte de l'échec inévitable de son mariage et entreprend de se rapprocher de son mentor tandis que Thérèse devine la nature inextinguible des sentiments de Beethoven envers la comtesse. Thérèse aussi ne demeurera qu'une amie et Beethoven un génie solitaire...

Procédant par touches impressionnistes, par une beauté visuelle, tout autant que sonore, « Les Saisons » se place dans le sillage de l'émerveillement permanent, de l'apologie de la beauté de notre nature. Grâce à une véritable prouesse technique, nous approchons au plus près des habitants de nos forêts, les voyant naître, grandir, mourir... A tel point que nous nous identifions aux cerfs, loups, lynx, ours, renards, sangliers et autres multiples espèces d'oiseaux qui constituent la diversité de notre faune, autant d'animaux qui font le bonheur des lecteurs de « La Salamandre » et de « La Hulotte ». Sans parler de la beauté des éléments (pluie, neige, vent, orage, aurore, crépuscule, nuit, pleine lune, etc.). Le film réussit également à nous montrer l'apparition des hommes au cœur de cette nature par petites touches comme si nous n'étions pas l'élément central de cette nature, mais l'un des hôtes.

Procédant par touches impressionnistes, par une beauté visuelle, tout autant que sonore, « Les Saisons » se place dans le sillage de l'émerveillement permanent, de l'apologie de la beauté de notre nature. Grâce à une véritable prouesse technique, nous approchons au plus près des habitants de nos forêts, les voyant naître, grandir, mourir... A tel point que nous nous identifions aux cerfs, loups, lynx, ours, renards, sangliers et autres multiples espèces d'oiseaux qui constituent la diversité de notre faune, autant d'animaux qui font le bonheur des lecteurs de « La Salamandre » et de « La Hulotte ». Sans parler de la beauté des éléments (pluie, neige, vent, orage, aurore, crépuscule, nuit, pleine lune, etc.). Le film réussit également à nous montrer l'apparition des hommes au cœur de cette nature par petites touches comme si nous n'étions pas l'élément central de cette nature, mais l'un des hôtes.

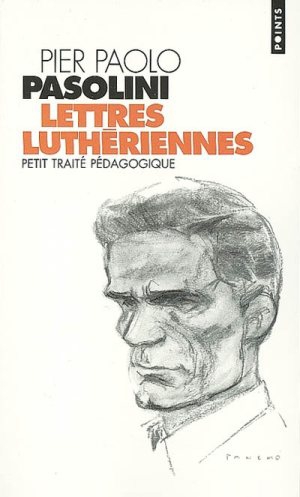

Le nouveau pouvoir consumériste impose ainsi un conformisme en accord avec l'air du temps utilitariste : la morale, la poésie, la religion, la contemplation, ne sont plus compatibles avec l'impératif catégorique de jouir du temps présent. L'art qui se nourrit des passions humaines les plus tragiques et les plus violentes n'a plus sa place dans un monde soumis aux stéréotypes médiatiques et aux discours officiels. À quoi servent encore des livres qui transmettent une représentation d'un monde passé dans une société exclusivement tournée sur elle-même ?

Le nouveau pouvoir consumériste impose ainsi un conformisme en accord avec l'air du temps utilitariste : la morale, la poésie, la religion, la contemplation, ne sont plus compatibles avec l'impératif catégorique de jouir du temps présent. L'art qui se nourrit des passions humaines les plus tragiques et les plus violentes n'a plus sa place dans un monde soumis aux stéréotypes médiatiques et aux discours officiels. À quoi servent encore des livres qui transmettent une représentation d'un monde passé dans une société exclusivement tournée sur elle-même ?

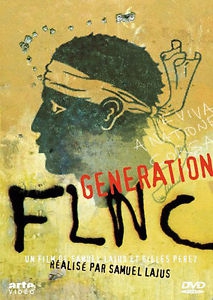

Eté 1975 sur l'Ile de beauté, Edmond a finalement choisi entre la canne à pêche et le fusil. Dès l'année suivante, différents groupuscules unissent leurs forces et créent le Front de Libération Nationale Corse et célèbrera joyeusement sa naissance par une spectaculaire nuit bleue. Le sigle F.L.N.C. se popularise très rapidement au-delà des côtes corses et inquiète fortement les services français. Les nombreuses arrestations et mises en détention n'entament en rien la progression de l'idée nationaliste en Corse. Aussi, est-il inconcevable de ne pas attribuer au Front les avancées des revendications corses. Si la lutte armée contre le trafic de drogue divise la population, tous les Corses, à l'exception de certains propriétaires fonciers peu regardants, approuvent le plasticage des résidences construites sur le littoral, afin que la Corse ne devienne pas la Costa del Sol. Pourtant, les tensions grandissent et les nationalistes s'engluent dans les affaires jusqu'à l'assassinat du préfet Erignac qui consomme un certain divorce entre partisans de la lutte armée et peuple corse.

Eté 1975 sur l'Ile de beauté, Edmond a finalement choisi entre la canne à pêche et le fusil. Dès l'année suivante, différents groupuscules unissent leurs forces et créent le Front de Libération Nationale Corse et célèbrera joyeusement sa naissance par une spectaculaire nuit bleue. Le sigle F.L.N.C. se popularise très rapidement au-delà des côtes corses et inquiète fortement les services français. Les nombreuses arrestations et mises en détention n'entament en rien la progression de l'idée nationaliste en Corse. Aussi, est-il inconcevable de ne pas attribuer au Front les avancées des revendications corses. Si la lutte armée contre le trafic de drogue divise la population, tous les Corses, à l'exception de certains propriétaires fonciers peu regardants, approuvent le plasticage des résidences construites sur le littoral, afin que la Corse ne devienne pas la Costa del Sol. Pourtant, les tensions grandissent et les nationalistes s'engluent dans les affaires jusqu'à l'assassinat du préfet Erignac qui consomme un certain divorce entre partisans de la lutte armée et peuple corse.

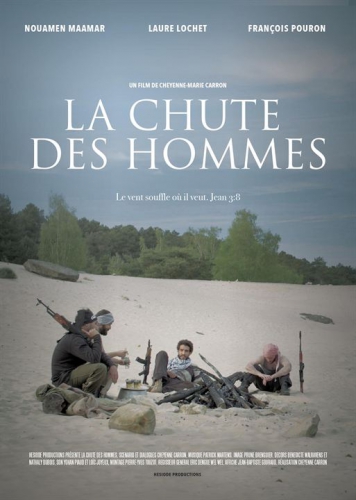

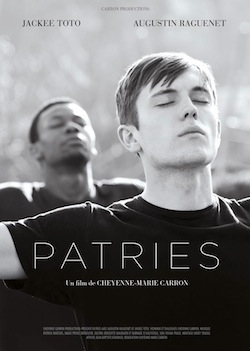

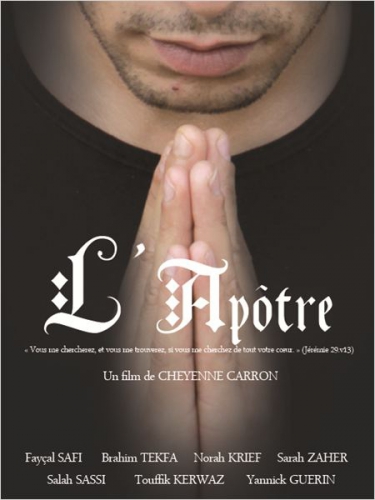

La bataille des régionales aura pour enjeu important la question des subventions attribuées au secteur culturel, là où la droite, suivie de la gauche, sont intervenues pour largement subventionner nombre d’associations dont la vocation consiste à détruire les structures traditionnelles, culturelles et artistiques de notre pays au détriment de créateurs, artistes, écrivains, cinéastes, revues, groupements de préservation de nos racines et traditions qui constituent les fondements même de notre avenir. Cheyenne-Marie Carron est, parmi de nombreux autres, l’exemple vivant de cette injustice et de ces dysfonctionnements.

La bataille des régionales aura pour enjeu important la question des subventions attribuées au secteur culturel, là où la droite, suivie de la gauche, sont intervenues pour largement subventionner nombre d’associations dont la vocation consiste à détruire les structures traditionnelles, culturelles et artistiques de notre pays au détriment de créateurs, artistes, écrivains, cinéastes, revues, groupements de préservation de nos racines et traditions qui constituent les fondements même de notre avenir. Cheyenne-Marie Carron est, parmi de nombreux autres, l’exemple vivant de cette injustice et de ces dysfonctionnements.

Lars von Trier, of course, thrives on such reactions. His aim is to disturb and unnerve, to stir the viewer out of his seat and out of his comfort zone. This is done not simply for the ‘shock value’ in itself, as there is no legitimate artistic worth in managing to provoke or enrage the audience; instead this is done in order to communicate something through the shocking material. By knocking the viewer out of his ordinary perspective, where everything is comfortably perceived and organized according to a familiar worldview, Lars von Trier can assault him with a new perspective, a new challenge that might threaten his old way of viewing reality.

Lars von Trier, of course, thrives on such reactions. His aim is to disturb and unnerve, to stir the viewer out of his seat and out of his comfort zone. This is done not simply for the ‘shock value’ in itself, as there is no legitimate artistic worth in managing to provoke or enrage the audience; instead this is done in order to communicate something through the shocking material. By knocking the viewer out of his ordinary perspective, where everything is comfortably perceived and organized according to a familiar worldview, Lars von Trier can assault him with a new perspective, a new challenge that might threaten his old way of viewing reality.

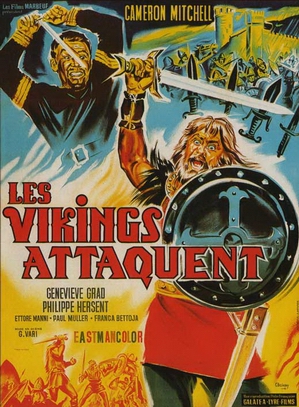

Au 9ème siècle, nombre de seigneurs anglais s'affrontent pour établir et consolider leur pouvoir. Wilfred, neveu du roi Dagobert est un jeune intriguant. Faisant la cour à la reine Patricia, il parvient à faire retenir prisonnier le Roi et porter les soupçons de félonie sur des contingents Normands, commandés par Olaf, établis sur ses terres et souhaitant y demeurer pacifiquement. Olivier d'Anglon, un jeune comte, s'éprend de Svetlana qu'il pense être la fille du chef viking mais qui se révèle en réalité être la fille issue des premières noces de Dagobert. A l'intrigue amoureuse, se joint la cupidité de Wilfred à qui Dagobert refuse de faire connaître la cachette de son trésor. Le sang ne peut que couler...

Au 9ème siècle, nombre de seigneurs anglais s'affrontent pour établir et consolider leur pouvoir. Wilfred, neveu du roi Dagobert est un jeune intriguant. Faisant la cour à la reine Patricia, il parvient à faire retenir prisonnier le Roi et porter les soupçons de félonie sur des contingents Normands, commandés par Olaf, établis sur ses terres et souhaitant y demeurer pacifiquement. Olivier d'Anglon, un jeune comte, s'éprend de Svetlana qu'il pense être la fille du chef viking mais qui se révèle en réalité être la fille issue des premières noces de Dagobert. A l'intrigue amoureuse, se joint la cupidité de Wilfred à qui Dagobert refuse de faire connaître la cachette de son trésor. Le sang ne peut que couler...

For the sake of argument I have been deliberately selective and will focus specifically on Uli Edels’s Baader Meinhof Complex and Enzo De Camillis’s fifteen minute short A Student named Alexander. Risking the approbation of cultural commentators by possibly extrapolating too general a hypothesis from too limited a sample, I nevertheless press my case, that the content, reaction and intent of both these films exemplify the paradox of Left/Right caricatures in the entertainment media.

For the sake of argument I have been deliberately selective and will focus specifically on Uli Edels’s Baader Meinhof Complex and Enzo De Camillis’s fifteen minute short A Student named Alexander. Risking the approbation of cultural commentators by possibly extrapolating too general a hypothesis from too limited a sample, I nevertheless press my case, that the content, reaction and intent of both these films exemplify the paradox of Left/Right caricatures in the entertainment media.

And if that is indeed the case, why not tell the story of one of the murdered MSI Youth Front members, Sergio Ramelli, 18; Francesco Cechin, 19; and Paolo Di Nella, 20, contemporaries of Alexander Caravillani (picture) and Mambro, who met their deaths by beating, shooting, and stabbings from Leftist brigands like the Autonomus Workers in the late ’70s and early ’80s? But of course, that will never happen. It does fit their agenda.

And if that is indeed the case, why not tell the story of one of the murdered MSI Youth Front members, Sergio Ramelli, 18; Francesco Cechin, 19; and Paolo Di Nella, 20, contemporaries of Alexander Caravillani (picture) and Mambro, who met their deaths by beating, shooting, and stabbings from Leftist brigands like the Autonomus Workers in the late ’70s and early ’80s? But of course, that will never happen. It does fit their agenda.