Archives de Synergies Européennes - 1988

Le message national du cinéma allemand

par Guy CLAES

Jadis, le passé s'évanouissait dans les brumes des souvenirs, se voyait transformé et déformé par les imaginations. Aujourd'hui, le passé demeure, fixé sur les bobines de celluloïde, archivé dans les cinémathèques. Les films sont notre néo-mémoire ; ils ont démocratisé l'histoire qui, désormais, ne se stocke plus uniquement dans les crânes de quelques élites motrices, mais est directement accessible aux masses. La puissance de gérer, de dominer, de manipuler l'histoire appartient dorénavant à ceux qui produisent les images et les lèguent aux générations futures. Dès lors, une lutte s'engage – et nous le constatons dans nos journaux et l'observons sur nos écrans – pour l'organisation de la mémoire publique et collective. Quel sens va-t-on lui donner ? Avec quels critères va-t-on l'imprégner ?

Jadis, le passé s'évanouissait dans les brumes des souvenirs, se voyait transformé et déformé par les imaginations. Aujourd'hui, le passé demeure, fixé sur les bobines de celluloïde, archivé dans les cinémathèques. Les films sont notre néo-mémoire ; ils ont démocratisé l'histoire qui, désormais, ne se stocke plus uniquement dans les crânes de quelques élites motrices, mais est directement accessible aux masses. La puissance de gérer, de dominer, de manipuler l'histoire appartient dorénavant à ceux qui produisent les images et les lèguent aux générations futures. Dès lors, une lutte s'engage – et nous le constatons dans nos journaux et l'observons sur nos écrans – pour l'organisation de la mémoire publique et collective. Quel sens va-t-on lui donner ? Avec quels critères va-t-on l'imprégner ?

En Allemagne, pays vaincu et « rééduqué », le thème de l'histoire, et surtout de l'histoire mise en film, s'avère problématique, lancinant, omniprésent et obsessionnel. L'histoire y sera jugée de façon critique, par des intellectuels inquiets, soucieux de ne pas enfreindre les comportements imposés, les tabous dictés par les psychologues affectés auprès de la police militaire américaine. La psychologie de l'intellectuel allemand, du Ouest-allemand qui joue et crée avec les opinions pour matériaux, diffère radicalement de celle de son homologue français, plus assuré, plus affirmateur, qui, s'il est « patriote » comme un Pierre Chaunu, rayonne de bonne conscience et forge de beaux écrits apologétiques. Le Français a une « patrie facile », l'Allemand a une « patrie difficile » (Ein schwieriges Vaterland).Et cette « difficulté » se répercute, de façon fantastique et étonnante, chez les cinéastes allemands modernes et dans leurs belles productions.

De l'image au débat sur l'histoire

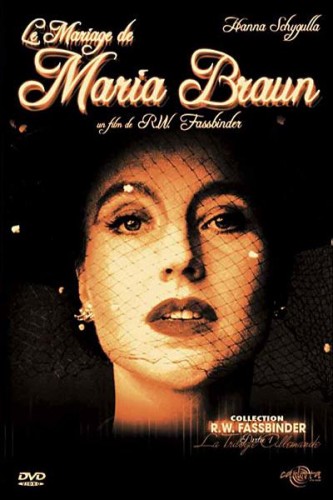

Comment cette angoissé face à l'histoire peut-elle, malgré les limites qu'elle impose à la pensée, se transfigurer de manière si captivante dans les films ? Parce que, écrit Anton Kaes, les images, couplées aux textes parlés et aux sons, relèvent d'une matérialité pluri-codée, génératrice d'une esthétique complexe, qui permettent de jouer sur les ambivalences et, simultanément, de suggérer au spectateur plusieurs significations à la fois. Le film de fiction, à connotations historiques, permet ainsi d'activer, chez le spectateur, des désirs et des angoisses cachés, de libérer des fantaisies, d'interpeller des sentiments collectifs inconscients et de catalyser des opinions. En bref: de titiller le refoulé, de le ramener à la surface. Ainsi, le film de Syberberg sur Hitler, Die Patriotin d'Alexander Kluge, Die Ehe der Maria Braun de Fassbinder et Deutschland bleiche Mutter de Helma Sanders-Brahm, ont tous déclenché un débat sur l'identité nationale à la fin des années 70. L'œuvre cinématographique donnait lieu et prétexte à un « événement » d'ordre discursif. Les critiques ne pouvaient plus se limiter à une simple analyse du film en tant que film mais devaient passer à un stade complémentaire et se plonger dans un débat sur l'histoire, imposé par la multiplicité des significations, véhiculée par les images.

Les critiques de cinéma étaient donc plus ou moins contraints de se mettre à l'écoute de l'histoire et, en outre, de se récapituler l'histoire du cinéma allemand, marquée par l'autorité de Goebbels. Ce dernier était parfaitement conscient de l'importance de la technique cinématographique, écrit Anton Kaes. Pendant l'hiver 1944/45, quand le IIIème Reich agonise, quand ses villes brûlent sous le phosphore des «soldats du Christ» et de son ayant-droit auto-proclamé, Roosevelt, quand ses dirigeants se réfugient dans leurs taupinières de béton, quand les meilleurs régiments sont saignés à mort, Veit Harlan, le cinéaste-vedette de l'époque, reçoit l'ordre de tourner un film en couleurs sur l'épisode de la bataille de Kolberg au XVIIIème siècle. Ce fut, malgré la disette et la ruine, le film le plus onéreux produit pendant l'ère hitlérienne. 187.000 soldats et 4.000 matelots sont détachés du front pour servir de figurants ! La première présentation publique a lieu le 30 janvier 1945, juste douze ans après la prise du pouvoir, dans la ville charentaise de La Rochelle, assiégée par les alliés. Quelques jours plus tard, les rares cinémas non détruits de Berlin passent le film sous les hurlements des sirènes, les vrombissements des bombardiers et l'explosion des bombes. Ce surréalisme fou et tragique témoigne de la foi aveugle qu'a cultivée le IIIème Reich à l'égard de la puissance démagogique des images mobiles.

Le IIIème Reich, c'est un film

Pour Goebbels, cette foi était calculée. Anton Kaes rappelle un de ses derniers discours, prononcé le 17 avril 1945, quelques jours avant son suicide. Devant un groupe d'officier, le Ministre de la Propagande prononce ces paroles si significatives : « Messieurs, dans cent ans on montrera un beau film en couleurs sur les jours terribles que nous vivons aujourd'hui. Voulez-vous jouer un rôle dans ce film ? Alors tenez bon maintenant pour que, dans cent ans, les spectateurs ne vous huent et ne vous sifflent pas lorsque vous apparaîtrez sur l'écran ! ». Cette exhortation reflète toute la prétention esthétisante du nazisme: jusqu'au bout, ce régime et cette idéologie ont mis la simulation, le tragique, l'esthétisme, le geste à l'avant-plan.

Pour Kaes, comme pour les jeunes cinéastes ouest-allemands, le « IIIème Reich », c'est un film. La scène de ce film, c'est l'Allemagne. Le producteur, c'est Hitler. Goebbels, c'est le metteur en scène. Albert Speer, c'est le décorateur. Le peuple, c'est l'ensemble des figurants. Et en effet, dès le premier jour du régime jusqu'à sa fin apocalyptique, la production d'images n'a pas cessé. Tous les films, les longs métrages comme les documentaires et les actualités, étaient contrôlés par la « Reichsfilmkammer » et Goebbels participait souvent personnellement au découpage. Jamais un État ne s'est préoccupé de façon aussi obsessionnelle de cinéma, reconnaissant par la même occasion sa fonction pédagogico-politique. Grâce au film, expliquait Goebbels, on peut éduquer le peuple sans lui donner l'impression qu'il se fait éduquer, la meilleure propagande est celle qui demeure invisible.

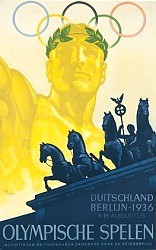

Quant aux films de propagande proprement dits, ils devaient subjuguer les masses par leur monumentalité. Mais la monumentalité n'est pas le seul atout de ce type de cinéma; dans Le Triomphe de la Volonté de Leni Riefenstahl, classique du genre, la caméra perpétuellement mobile parvient à dynamiser tout : les espaces, les formations humaines, les monuments de pierre. La symbolique suggérée par les jeux de lumière s'ajoute à cette mouvance enivrante qu'un Robert Brasillach ou un Pierre Daye ont constaté de visu. Ces images de propagande, ce dynamisme cinématographique légué par Leni Riefenstahl, nous les avons intériorisés ; ils font partie de notre mémoire vive ou dormante.

Présence et jouvence du IIIème Reich dans les films

Le IIIème Reich, dont la politique cinématographique fut rigoureusement planifiée, semble avoir de ce fait trouvé le secret de l'éternelle jouvence, la force de rester, en dépit des vicissitudes tragiques de l'histoire, pour toujours parmi nous. Goebbels nous a imposé et continue à nous imposer sa vision esthétique, son image du politique, son dynamisme total, comme nous l'indique son discours du 17 avril 1945. Les adversaires du régime n'existent plus parce qu'ils n'ont pas été filmés, si bien que leurs problèmes disparaissent, semblent n'avoir pas été parce qu'aucune image ne témoigne d'eux. Les images acquièrent une réalité plus prégnante que le réel et possèdent une dimension plus mobilisatrice, comme le prouvent aussi les innombrables albums illustrés sur le IIIème Reich qu'on trouve à profusion dans le commerce et comme l'attestent également les « contre-images » qui dévoilent l'univers concentrationnaire.

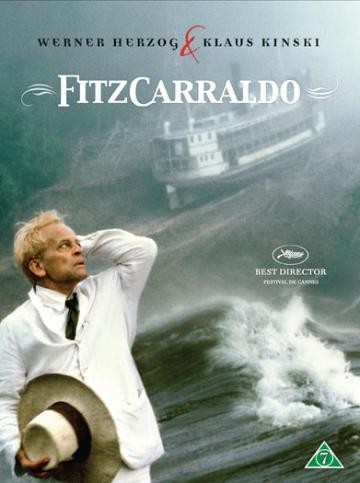

Cette conquête du futur, partiellement réussie par Goebbels, a été possible par l'émigration forcée de cinéastes comme le génial Fritz Lang qui voulait s'affranchir des impératifs politiques et ne pas passer sous les fourches caudines du parti au pouvoir. En dehors du cinéma nazi, il ne subsistait rien. Après la défaite, le public allemand et sa nouvelle intelligentsia cultiveront une méfiance instinctive à l'égard du cinéma dont les productions les plus connues avaient été marquées du sceau goebbelsien. La tradition cinématographique allemande, dans laquelle s'inscrivait Fritz Lang, avait été brisée et la tradition de Goebbels n'était plus de mise. Les nouveaux producteurs durent dès lors imiter les modèles américains ; Werner Herzog fut l'un des premiers à renouer avec la tradition des expressionnistes allemands des années 20. Schlöndorff s'inspira de ses collègues français. En 1962, vingt-six cinéastes et journalistes proclament le « Manifeste d'Oberhausen », où il est annoncé que le « cinéma de Papa » est mort. Les signataires envisagent l'avènement d'un cinéma « critique » qui doit remplacer la vogue des variétés dépolitisées et dépolitisantes, tout comme le « Groupe 47 » doit rénover la littérature. Suivant l'exemple des Français Godard, Truffaut et Chabrol, ils estiment que tout film doit porter la signature indélébile de son auteur.

Le souci « moral »

Le « Manifeste d'Oberhausen » trahit, comme les grands courants philosophiques contemporains en RFA ou comme les principes qui animent les tenants du « Groupe 47 » en littérature, un souci « moral », un souci de hisser la « morale » au-dessus du politique, de l'histoire et de l'instinct de conservation. Mais cette démarche « moralisatrice » va thématiser le rapport troublé qu'entretiennent les Allemands avec leur histoire, criminalisée par les vainqueurs de 1945 et sans cesse houspillée hors des mémoires. Les premiers Spielfilme du « jeune cinéma allemand » concernent directement ce passé problématique. L'Alsacien Jean-Marie Straub, installé en RFA, et sa compagne Danielle Huillet créent un cinéma rigoureusement détaché des variétés commerciales et calqué sur les œuvres littéraires de Heinrich Böll. Cette option se révèle clairement dans Machorka-Muff (1962), un court métrage inspiré par la satire de Böll, Hauptstädisches Journal (= Journal de la capitale). Le héros central du film est un ancien général de l'armée de Hitler, Erich von Machorka-Muff, qui réalise un fantasme : créer une « Académie des souvenirs militaires » où les militaires, à partir du grade de major, peuvent se retirer pour y écrire leurs mémoires. La première conférence prononcée dans cette institution porte, très significativement, le titre de « Le souvenir comme mission historique ». Straub et Huillet voulaient souligner par là que l'important, ce n'était pas les nostalgies des vieux soldats mais la volonté de dépasser l'amnésie installée pendant le miracle économique.

Ce retour discret à l'histoire, grèvé de ce sentiment de lourde culpabilité, qui agace parfois les nonAllemands, Straub et Huillet l’ont opéré par le biais d'une technique cinématographique diamétralement contraire aux techniques de Leni Riefenstahl. Tout grandiose est évacué et on voit apparaître un véritable ascétisme vis-à-vis des images. La caméra reste statique ; les acteurs déclament leur texte de façon un peu scolaire, afin que le caractère de fiction puisse bien apparaître, comme le préconisait Bertold Brecht. Ce genre de film est accueilli avec enthousiasme à l'étranger, lors des festivals, mais ne suscite pas les faveurs des masses. Il reste donc un pur produit intellectuel, en marge des préoccupations de monsieur-tout-le-monde, plus friand de sensationnel et de narratif.

Le choc de la « Bande à Baader »

Ce divorce entre la réflexion sur l'histoire refoulée et les désirs immédiats de la population perdurera jusqu'en 1977. Cette année-là est la grande année de la Rote Armee Fraktion (RAF) ou « Bande à Baader ». Ce groupe terroriste urbain assassine consécutivement le Procureur Buback, le banquier Ponto et le « patron des patrons » Schleyer. La tension culmine en octobre quand des camarades de Baader, emprisonné à Stammheim, détournent un avion vers Mogadiscio en Somalie avant de se faire neutraliser par un commando spécial. Baader, Raspe et Gudrun Ensslin se « suicident » alors mystérieusement dans leurs cellules. Cette situation de crise provoque la naissance d'un néo-macchartysme, d'une censure à l'endroit de tout ce qui peut apparaître comme non conformiste.

Dans le monde des cinéastes, Margarethe von Trotta, dans son film Die bleierne Zeit (= Temps de plomb ; 1981), se penche sur la personnalité de Gudrun Ensslin, la suicidée de Stammheim. Ce qui a conduit la jeune Gudrun au terrorisme urbain, c'est la prise de conscience des horreurs du nazisme ; elle s'imagine, qu'en tant qu'Allemande, elle porte une « marque de Caïn » indélébile qu'il faut racheter en luttant contre les injustices d'aujourd'hui et les reliquats du passé, portés par les « parents ». Moins simplificateur, le philosophe Norbert Elias estime que ce ne sont pas, en règle général, les « parents », en tant qu'êtres concrets et vivants, qui ont provoqué le déclic fatal mais les livres scolaires et l'école, mis au pas par la rééducation. Le lavage de cerveau conduirait ainsi au paroxysme terroriste.

Oublier l'histoire ou s'y replonger

En triturant l'histoire, en la violentant, le système de la « rééducation » n'a pas apaisé les Allemands comme l'auraient voulu les Alliés occidentaux, ne les a pas réinsérés dans cette vieille, traditionnelle et paisible acceptance romantique d'une réalité internationale pré-bismarckienne qui leur assigne à perpétuité une place de seconde zone, dans cette douce et insouciante Gemütlichkeit du « Bon Michel » sans industrie et sans armée, mais, au contraire, les a jetés dans une angoisse atroce, dans un déchirement perpétuel, générateur de terrorisme, producteur de desperados à la Baader. Et la censure anti-terroriste, la chasse aux sorcières néo-macchartyste de l'automne 1977, n'a fait qu'amplifier cette angoisse, ce processus de refoulement constant, où l'inquisiteur, en traquant le non-conformiste soupçonné de sympathiser avec les terroristes, traque aussi un pan entier de sa propre sensibilité, de son intériorité,

L'affaire Baader provoque finalement un désir général de renouer avec l'histoire. À la version officielle de l'événement, un collectif de cinéastes répond par un film critique Deutschland im Herbst (= L'Allemagne en automne), où, par l'intermédiaire d'images d'archives, les spectateurs peuvent comparer l'assassinat de Rosa Luxemburg au « suicide » et à l'enterrement furtif et hyper-surveillé de Baader et de ses deux camarades, l'enterrement officiel du Maréchal Rommel, présenté comme dissident, et l'enterrement de Schleyer, victime de la RAF.

Le défi d'Holocauste

Cette timide amorce d'une réinvestigation de l'histoire n'a pas atteint le grand public et est resté affaire d'intellectuels contestataires. Une année plus tard, la série américaine Holocauste, elle, replonge directement les téléspectateurs dans l'histoire et interpelle sans détours les Allemands, détenteurs des mauvais rôles, comme il se doit à notre époque. Holocauste provoque un débat malgré la médiocrité stéréotypée de son intrigue, l'absence de tout goût dans sa réalisation générale et son kitsch flagrant. Ce sera Élie Wiesel qui aura les mots les plus durs pour dénigrer la série ; dans un article du New York Times, en date du 16 avril 1978, le futur Prix Nobel ne mâche pas ses mots ; écoutons ses paroles : « En tant que production de télévision, le film constitue une injure à l'égard de ceux qui ont périt et de ceux qui ont survécu. (...). Suis-je trop dur ? Trop sensible peut-être. (...) [Ce film] transforme un événement ontologique en une opérette (soap-opera). Quelqu'aient été les intentions de ses réalisateurs, le résultat est choquant. Des situations imaginées, des épisodes sentimentaux, des hasards non crédibles : (...). Holocauste, c'est un spectacle télévisé. Holocauste, c'est un drame de télévision. Holocauste, mi-fait, mi-fiction. N'est-ce pas exactement ce que de nombreux "experts" moralement égarés ont fait valoir partout dans le monde, ces derniers temps ? C'est-à-dire ont affirmé que l'holocauste n'est rien de plus qu'une "invention" ? (...). L'holocauste doit rester gravé dans nos mémoires, mais pas comme un show ».

Sabina Lietzmann, collègue de Wiesel à la Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, se place sur la même longueur d'onde dans un article paru le 20 avril 1978 ; pour elle, qui vient de visionner le film avant le public, Holocauste transforme le martyr des Juifs en opérette. Le 28 septembre 1978, elle révise son jugement, expliquant que le film a son utilité, sa fonction, qui est de renforcer et dépasser en efficacité les arguments du purisme rationnel. Le niveau de la « story », qui est celui d'Holocauste, permet un accès immédiat à l'histoire de l'anéantissement des Juifs, lequel demeurerait sinon incompréhensible à la raison courante, selon Sabina Lietzmann. L'intelligentsia juive a donc changé d'attitude à l'endroit de la production télévisée : hostile au départ, parce qu'elle trouvait la trame narrative trop grossière, son attitude s'est muée en enthousiasme devant le succès du film et l'étonnante naïveté du public européen

Die Patriotin d'Alexander Kluge

En Allemagne, le défi lancé par Holocauste, sa réception mitigée chez les Juifs et hostile chez les Nationalistes, ouvrent l'écluse : l'histoire entre à gros flots dans une société qui avait voulu l'oublier pour toujours et l'avait refoulée sans merci. Les « nouveaux » Allemands ont voulu prouver qu'ils ne correspondaient plus aux stéréotypes des nazis caricaturaux que donnaient d'eux les producteurs américains. L'histoire allemande, disaient-ils, ne devait plus être traitée exclusivement par l'« esthétisme commercial » américain. L'histoire allemande doit être traitée sur les écrans par des cinéastes allemands ; ils ont le devoir de ne pas se la laisser arracher des mains.

Kaes estime que la meilleure réponse à Holocauste a été Die Patriotin (= La patriote) d'Alexander Kluge, primée en septembre 1979. Ce film, commencé deux ans plus tôt, s'oppose radicalement à la série hollywoodienne sur le plan du style. Kluge rejette tout fil conducteur narratif, toute fiction sans épaisseur, toute cette platitude d'historiette. Son œuvre, de portée philosophique, de teneur non propagandiste, indique la perte qu'ont subie les Allemands : leur histoire est désormais détachée de tout continuum ; elle est devenue un puzzle défait, un chaos de morceaux épars, d'où l'on ne retire que du désorientement. Comme l'écrivait Lyotard, l'ère post-moderne est l'ère qui a abandonné les grands récits idéologiques explicatifs pour morceler le réel au gré des options individuelles. L'Allemagne a renoncé à comprendre les lames de fonds de son histoire multi-millénaire – parce qu'on la lui a criminalisée – pour butiner, erratique, autour des feux follets occidentaux, consuméristes, matérialistes.

Une nouvelle conception de l'histoire

La figure centrale de Die Patriotin est une enseignante, professeur d'histoire, Gabi Teichert. Cette femme cherche, au-delà de sa fonction, à renouer plus intimement avec le passé de son pays, l'Allemagne. Symboliquement, on la voit se transformer en archéologue-amateur qui gratte le sol pour découvrir des restes dispersés d'une histoire deux fois millénaire qui ne peut plus être mise sous un dénominateur commun. Fouiller ce vaste chantier, apporte au moins une conviction : l'histoire ne peut se réduire aux simplismes consignés hâtivement dans les manuels scolaires. Il n'y a pas une histoire mais beaucoup d'histoires ; il n'y a pas un « grand récit » (pour paraphraser Lyotard) mais un tissu complexe de milliers de « petits récits » enchevêtrés.

La « nouvelle histoire », c'est précisément la méthode historique qui doit réhabiliter ces « petits récits », lesquels deviennent la chape sous-jacente d'un « nouveau patriotisme ». Ce patriotisme n'exalte plus une construction politique, une machine étatique – l'idéologie dominante de gauche ne l'aurait pas accepté – mais chante un espace qui accouche perpétuellement d'une identité, un espace auquel on est lié par la naissance et l'enfance, la langue et les premières expériences de la vie. La gauche, après la faillite de la stratégie terroriste en 1977, se met à vouer un culte à la Heimat, socle incontournable, fait de monde plus durable que les gesticulations policières ou politiciennes, que les déclamations idéologiques ou l'agressivité terroriste. La « population » devient la nouvelle réalité centrale, les hommes et les femmes de chair et de sang, plutôt que les éphémères avant-gardes du prolétariat ou les porteurs de la « conscience de classe ». L'échec de la révolte urbaine de 68, l'enlisement de ses revendications dans le marais du libéral-consumérisme occidental, induit quelques-uns de ses protagonistes à renoncer aux utopies grandiloquentes, sur fond de stagnation, de croissance ralentie. Le réel le plus fort, puisque le plus stable, c'est cette dimension du « terroir » éternel, de cet oikos initial de la personnalité de chacun.

Le patriotisme de Gabi Teichert

Die Patriotin met symboliquement cette mutation du patriotisme en scène. D'entrée de jeu, la première image sur l'écran, c'est un mot : "DEUTSCHLAND", thème qui va être placé sous la loupe. Très concrètement, la réalité allemande, c'est d'abord un paysage heimatlich, un terroir, un horizon bien circonscrit. Les premières images de Kluge semblent issues d'un documentaire touristique : des campagnes riantes, des champs, des prés, des arbres fruitiers en fleurs, les ruines d'un vieux château, des forêts. Ce survol s'opère sur un texte déclamé par un os de genou, découvert par Gabi Teichert, symbole d'un morceau du passé. Il dit : « On dit que je suis orienté historiquement. C'est juste, évidemment. L'histoire ne me quitte pas l'esprit car je suis partie d'un tout, comme mon ancien maître le caporal Wieland, était aussi partie d'un tout : une partie de notre belle Allemagne. (...). En tant que genou allemand, je m'intéresse tout naturellement à l'histoire allemande : à ses empereurs, à ses paysans, à ses récoltes, à ses arbres, à ses fermes, à ses prés, à sa flore... ».

Derrière l'ironie de ce discours prononcé par un genou de caporal arraché, se profile ce glissement, observable au cours des années 70, des utopies progressistes aux utopies écolo-passéistes. Dans l'orbite de ce glissement idéologique majeur de notre temps, le nationalisme de vieille mouture en vient à signifier l'éloignement d'« hommes du peuple » dans des champs de bataille lointains. Le patriotisme nouveau signifie, au contraire, la proximité du terroir. Kluge symbolise cette opposition par des images de Stalingrad, avec des soldats affamés, défaits, hâves, aux membres gelés, ce qui constitue un contraste affreux entre une steppe enneigée, si lointaine, et une patrie charnelle chaleureuse et idyllique. L'histoire est ici instance ennemie ; elle procède d'une logique qui tue le camarade ressortissant du même peuple que le mien. Si le paysage du terroir est baigné de soleil, le champ de bataille russe où se joue l'histoire est gelé, glacé, frigorifié. De l'hiver de Stalingrad à la froidure de l'Allemagne de Bonn, sortie de l'histoire, voilà l'itinéraire navrant d'une Allemagne qui ne peut plus renouer avec son passé romantique, musical et nationaliste.

Les Allemands victimes

Kluge truffe Die Patriotin de morceaux de films alliés d'actualité : des pilotes américains bombardent une ville allemande tout en plaisantant grossièrement; de jeunes résistants allemands, des Wehrwölfe, sont fusillés par les Alliés en 1945 ; les commentaires en off qui accompagnent ces images tragiques sont sarcastiques : « Ces pilotes de bombardier reviennent de leur mission. De l'Allemagne, ils n'ont rien appris de précis. Ils ont simplement détruit le pays pendant dix-huit heures de façon professionnelle. Maintenant, ils rejoignent leurs quartiers ; ils vont dormir ». Ou : « Nous ne voulons pas oublier que 60.000 personnes sont mortes brûlées dans Hambourg ». De tels commentaires induisent les spectateurs à percevoir les Allemands comme victimes d'orgies destructrices, de la guerre, de bombardements, de captivités et de fusillades. La personnalité de Gabi Teichert, professeur d'histoire en pays de Hesse, incarne dès lors le souvenir de tous ces morts issus du Reich, souvent victimes innocentes de la guerre totale.

Finalement, Kluge est très barrèsien : sa sentimentalité patriotique participe d'un culte doux de la Terre –réceptacle de gentillesse, de Gemütlichkeit, d'apaisement – et des Morts, dont on ne peut perdre le souvenir, dont on ne peut oublier les souffrances indicibles. L'Allemagne, ce n'est pas seulement un système étatique né en 1871 et durement étrillé en 1918 et en 1945, c'est surtout un corps vivant, vieux de deux millénaires, un produit de l'histoire façonné par 87 générations, une fabrique d'expériences collectives, un réceptacle de souvenirs. L'Allemagne est une cuisine gigantesque où une force de travail collective n'a jamais cessé de produire des mutations historiques. L'Allemagne véritable est un magma toujours en fusion, jamais achevé. L'Allemagne véritable ne se laisse pas enfermer dans une structure étatique figée. Laboratoire fébrile, l'Allemagne de Kluge et de son ami le philosophe Oskar Negt, connaît ses bonnes et ses mauvaises saisons et, quand Gabi Teichert, à la fin du film, s'en va fêter la Saint-Sylvestre et récapitule l'année écoulée, elle sait que l'hiver présent finira et qu'un nouvel été adviendra, riche en innovations...

La révolte de Fassbinder

Célébrissime fut Rainer Maria Fassbinder, le cinéaste « gauchiste » mort à 37 ans en 1982 ; perçu à l'étranger comme l'incarnation du nouveau cinéma allemand, comme le fleuron de la conscience blessée des Allemands contemporains. Fassbinder, c'est la fougue et la colère d'une jeunesse à laquelle toute conscience politique est interdite et qui doit ingurgiter passivement les modèles de société les plus étrangers à son coeur profond. Souvent, l'on a dit que cette génération de l'« heure zéro » (Stunde Null), dont l'enfance s'est déroulée sous le signe du miracle économique, s'est rebellée contre la génération précédente, celle dite d'« Auschwitz », celle de l'ère hitlérienne. Mais davantage qu'une révolte des fils contre les pères, la révolte de Fassbinder et de ses contemporains est une révolte contre la parenthèse apolitique, anti-identitaire, économiste, inculte, du redressement allemand sous le règne d'Adenauer.

Dans cette optique, l'épisode de la révolte étudiante de 67-68 est une ré-irruption du politique, une explosion de sur-conscience politique. Sur-conscience qui s'est pourtant bien vite enlisée dans l'utopisme stérile puis dans l'amertume des désillusions. Toute l'œuvre cinématographique de Fassbinder témoigne de cet échec complet de l'utopisme rousseauistemarxisant.

Pour Fassbinder, le XXème siècle allemand est une suite ininterrompue d'échecs : l'échec du totalitarisme nazi, l'échec humain et psychologique de l'opulence économique, l'échec du romantisme utopiste de 67-68, l'échec du recours à la terreur. Aucune formule n'a pu exprimer pleinement l'essence véritable de la germanité ; celle-ci reste refoulée dans les consciences. Pour mettre en scène ce « manque » – Kluge parle lui aussi de « manque » – Fassbinder adoptera les techniques du cinéaste Douglas Sirk (alias Hans Detlef Sierck), exilé à Hollywood en 1937, après avoir servi la UFA allemande. Sirk/Sierck avait créé un cinéma inspiré des romans triviaux sans happy end, où les aspirations au bonheur sont contrecarrées par les aléas de la vie. Autres techniques : éclairages contrastés, utilisation symbolique d'objets quotidiens (fleurs, miroirs, tableaux, meubles, vêtements, etc.).

Le système « RFA » est un échec

Les premières œuvres de Fassbinder sont toutes marquées par le style de Sirk/Sierck. Quant aux œuvres majeures, proprement fassbinderiennes, elles sont malgré tout impensables sans l'influence de Sirk. Les destins de Maria Braun, de Lola, de Veronika Voss sont des destins privés, indépendants de tout engagement politique/collectif, qui aboutissent tous à l'échec. Mais ces destins que la fiction pose comme privés parce que la technique cinématographique l'impose, sont en fait symboles de l'Allemagne, d'une histoire nationale ratée, et ne sont plus simplement des cas sociologiques qu'un militant politique met en scène pour induire le public et les gouvernants à trouver un remède politicien. De 1970-72 jusqu'à la période des grands films fassbindériens, commencée en 1977, on constate un glissement progressif de l'engagement social critique à un engagement national également critique et farci d'une terrible amertume, celle qui conduira Fassbinder au suicide par overdose.

Le recours à l'histoire ne résulte pas, chez Fassbinder, d'une nostalgie de l'Allemagne romantique, impériale ou nationale-socialiste mais d'une volonté de critiquer sans la moindre inhibition ou réticence, l'évolution subie par la patrie depuis 1945. Cette année-là, pense Fassbinder, tout était possible pour l'Allemagne, toutes les voies étaient ouvertes pour créer ce que les Wandervögel avaient nommé le Jugendreich, pour créer l'État idéal dont avaient rêvé les mouvements de jeunesse. « Nos pères – écrit Fassbinder – ont eu des chances de bâtir un État qui aurait pu être tellement humain et libre qu'il n'aurait jamais soutenu aucune comparaison historique... ».

Une démocratie importée...

Mais la RFA, secouée d'hystérie à l'automne 1977, n'est pas l'État idéal, la société parfaite, l'harmonie rêvée. L'entrée de l'histoire sur l'écran, c'est, chez Fassbinder, une rétrospective hyper-critique des années 50 et 60, un refus implicite des institutions et des valeurs règnantes dans cette nouvelle république allemande. La démocratie ouest-allemande est une démocratie non spontanée, importée par des armées étrangères et non imposée par la propre volonté du peuple allemand. Il n'existe donc pas de la démocratie de mouture spécifiquement allemande. Ces sentiments politiques contestataires, la trilogie Die Ehe der Maria Braun, Lola, Die Sehnsucht der Veronika Voss, va les exprimer brillamment.

Sur le plan psychologique, ce démocratisme d'importation, cette misère allemande, procède d'une soumission des sentiments et des instincts à la logique du profit, à l'âpreté matérialiste, à la corruption, aux stratégies de l'opportunisme. Ce calcul mesquin, les hommes, rescapés des campagnes hitlériennes (dans les années 50, il reste 100 hommes pour 160 femmes), ont tendance à le pratiquer plus spontanément que les femmes, symbolisées par les héroïnes de Fassbinder. Survivre, s'accomoder, rechercher le nécessaire : voilà les activités qui ont donné lieu à un refoulement constant des souvenirs et des deuils. Comprendre les années 50, cela ne peut se faire qu'en répertoriant les « petits récits » qui forment le « texte », la texture (du latin, textum), de l'histoire. Cette texture est complexe, drue, serrée et Maria Braun en est un reflet, un symbole car plusieurs constantes s'entrecroisent et s'opposent en elle. Elle est un paradigme fictif incarnant divers « petits récits » réels. Examinons cet entrelas.

Le destin de Maria Braun

Maria Braun épouse quelques mois avant la fin de la guerre le fantassin Hermann Braun qui, après une nuit et un jour, retourne au front. Il est porté disparu et Maria, pour survivre, doit se mettre en ménage avec un gros et placide GI noir. Hermann revient, une querelle éclate, Maria frappe mortellement Bill le GI et Hermann, touché par la fidélité de sa compagne, prend la faute sur lui et purge une peine de prison. Maria lui promet que la vie réelle reprendra dès sa libération. Entre-temps, elle ne voit plus qu'une chose : le succès économique. Amour et sentiments sont remis à plus tard, postposés comme un rendez-vous sans réelle importance. Elle cède ensuite à Oswald, un fabricant de textile revenu d'émigration, et vit avec lui sans l'aimer tout en gravissant rapidement l'échelle hiérarchique de son entreprise. Cette cassure entre les sentiments humains et la vie quotidienne matérialiste, phénomène consubstantiel au démocratisme d'importation, à l'économisme libéral venu d'Outre-Atlantique, se résume dans un dialogue au parloir de la prison entre Hermann et Maria, à propos des relations humaines de l'après-nazisme : « C'est donc comme ça, dehors, entre les gens ? C'est si froid ? » demande Hermann, anxieux. Elle lui répond : « C'est un temps pas bon pour les sentiments, j'crois ».

L'opulence acquise par Maria croît et quand Hermann sort, il part d'abord en voyage et ne revient que lorsque meurt Oswald. Maria apprend alors que Hermann et Oswald avaient négocié derrière son dos: Oswald léguait la moitié de ses biens à Hermann, si celui-ci lui laissait Maria jusqu'à sa mort. Maria, incarnation de l'Allemagne non politisée, de l'Allemagne victime de forces extérieures, comprend enfin qu'elle a été sans cesse manipulée... Après cette révélation, la superbe villa d'Oswald, désormais propriété du couple, explose. La morale de cette histoire, quand on sait que Maria incarne l'Allemagne éternelle et Hermann l'Allemagne combattante de ce siècle, c'est qu'il n'y a pas de bonheur possible au bout du libéralisme marchand, apporté par les GI noirs et les fabricants de tissus revenus d'exil...

Le progressisme marchand est une fuite en avant

La leçon que veut inculquer Fassbinder à son public, c'est que nos vies privées sont déterminées par l'histoire politique, elle-même déterminée par les vicissitudes économiques. En Allemagne, ce paramarxisme fassbindérien se justifie quand on constate avec quelle insouciance les Allemands de l'Ouest ont accepté la partition du pays en 1949 ou oublié la révolte ouvrière de Berlin-Est de 1953. Seule la linéarité « progressiste/libérale » comptait : c'était finalement une fuite en avant, positivement sanctionnée par l'acquisition quantitative de bouffe, de fringues, de mobilier. Plus le temps d'une réflexion, d'une introspection. Cette société vit aussi la surabondance des messages : les personnages devisent sur fond de discours radiophoniques, sourds aux événements du monde et préoccupés seulement de leurs petits problèmes personnels. C'est l'avènement, dans la non-histoire, de l'égoïsme anthropologique ; Maria dissimule, feint, ment pour arriver à ses fins et dit, dans un moment d'honnêteté : « Je suis maîtresse dans l'art de la simulation. Je suis outil du capitalisme le jour et, la nuit, je suis agent des masses prolétariennes, la Mata Hari du miracle économique ».

Maria est tiraillée, comme l'Allemagne, entre les souvenirs et l'oubli (le refoulement volontaire). Cette dernière démarche, propre à l'établissement ouest-allemand, est une impossibilité : les souvenirs se diffusent dans l'atmosphère comme un gaz toxique et explosif. Si on ne prête pas attention, si l'on persiste à vouloir refouler ce qui ne peut l'être, la moindre étincelle peut faire exploser le bâtiment (l'environnement)... Jean de Baroncelli dans Le Monde (19/01/80) explique de façon particulièrement limpide que Maria Braun, qui « est » l'Allemagne, est devenue un être vêtu de très riches vêtements, mais qui a perdu son âme, en se muant en « gagneuse ».

Antisémitisme ?

Vient ensuite la phase la plus contestée de l'œuvre de Fassbinder : celle qui aborde le problème délicat de l'antisémitisme. Deux films du cinéaste n'ont pu être tournés et sa fameuse pièce Der Müll, die Stadt und der Tod (= Les ordures, la ville et la mort) n'a pu être jouée ni en 1976, quand elle fut achevée, ni en 1985, quand un théâtre a tenté de braver l'interdit. L'intrigue de cette pièce si contestée provient d'un roman de Gerhard Zwerenz, Die Erde ist unbewohnbar wie der Mond (= La Terre est inhabitable comme la Lune), dont la figure centrale est un spéculateur immobilier de confession israëlite, Abraham. C'est le stéréotype du « riche Juif » de la littérature antisémite. Le récit de la pièce, c'est la mort d'une ville, en l'occurence Francfort, qui est systématiquement mise en coupe réglée par des spéculateurs immobiliers, dont certains sont juifs. La population, dans de telles circonstances, devient un ensemble désorganisé et pantelant de « cadavres vivants » (comme le dit une prostituée dans la pièce), expurgés de toute épaisseur humaine.

Le tollé, soulevé par la pièce, fut énorme. Fassbinder fut accusé de fabriquer un « antisémitisme de gauche », un « fascisme de gauche ». Son éditeur, la Maison Suhrkamp, pourtant peu suspecte d'antisémitisme et fer de lance de la « nouvelle gauche », a dû retirer de la vente le texte de la pièce, sous la pression des « rééducateurs » patentés. L'historien Joachim Fest avait rédigé l'une des plus violente philippique contre le cinéaste dans la FAZ (19/03/1976), ce qui peut sembler paradoxal, puisqu'il sera lui-même victime de ce genre d'hystérie, lors de la parution de son Hitler - Eine Karriere en 1977, sous prétexte que le problème juif sous le IIIème Reich n'y était traité qu'en deux minutes et demie dans un film de deux heures et demie.

Dans la foulée, deux films de Fassbinder, dérivés du célèbre roman de Gustav Freytag Soll und Haben, seront interdits ou sabotés, parce que le cinéaste avait traduit en images cinématographiques les descriptions du ghetto, émaillant ce classique littéraire. Représenter le ghetto ne signifie pas en vouloir aux Juifs et manifester de l'antisémitisme, écrivit Fassbinder pour sa défense, mais au contraire dévoiler les conditions objectives dans lesquelles vivaient les Juifs en butte à l'antisémitisme. Si dans de telles circonstances, poursuit-il, des Juifs sont amenés à avoir un comportement vicié, c'est la conséquence de l'oppression qu'ils subissent. Ses adversaires rétorquent que le danger de ses films vient du simple fait d'opérer une monstration des comportements viciés, laquelle pourrait conduire à des mésinterprétations dangereuses. À cela, Fassbinder répond qu'il est inepte de présenter les Juifs à la manière philosémite, c'est-à-dire comme des victimes pures et blanches, car une telle démarche est l'inverse exact du manichéisme antisémite.

Ces raisonnements hétérodoxes font de Fassbinder un « anarchiste romantique », dans le sens où le vocable « anarchisme » signifie une radicale indépendance à l'égard des partis, des Weltanschauungen de gauche et de droite, de tous liens personnels et politiques. Son pessimisme, qui se renforce sans cesse quand il observe l'involution ouest-allemande, dérive du constat que les énergies utopiques positives, potentiellement édificatrices d'un État parfait, se sont épuisées et qu'en conséquence, l'avenir n'offre plus rien de séduisant. « L'avenir est occupé négativement », déplore Fassbinder qui cultive désormais le sentiment d'être assassiné en tant qu'« être créatif ». Conclusion qui sera suivie de son suicide : « Il n'y a pas de raison d'exister, lorsque l'on n'a pas de but ».

La vanité des espoirs de Fassbinder correspond à l'échec des gauches étudiantes qui avaient voulu « conscientiser » (horrible mot !) les masses en les dépouillant de tous leurs réflexes spontanés. L'impact en littérature et en cinéma de cet échec, c'est l'éclosion d'une « nouvelle subjectivité » qui vise à réhabiliter les identités individuelles, les expériences personnelles et les intériorités psychologiques, devant l'effondrement des « châteaux en Espagne » que furent les utopies militantes, marquées par les philosophies rationalistes. Ce fut là un retour volontaire à l'« authenticité », à la concrétude existentielle, confirmé par le flot de romans historiques, de biographies et de mémoires produits dans les années 70.

Le travail de Helma Sanders-Brahms

Ce retour, qui est aussi retour au passé, procède souvent d'une interrogation des parents, témoins de la « pré-histoire » du présent, à laquelle on retourne parce que les perspectives d'avenir sont réduites et que la nostalgie acquiert ainsi du poids. En cinéma, l'œuvre cardinale de la vogue « néo-subjectiviste » est, pour Kaes, Deutschland, bleiche Mutter (= Allemagne, mère blême), de Helma Sanders-Brahms. C'est le dialogue entre une fille et sa mère Lene, qui apparaît comme une victime souffrante de l'histoire allemande récente. Les stigmates de cette souffrance se lisent sur le visage ridé et ravagé de l'actrice principale, incarnation, comme Maria Braun, de l'Allemagne mutilée.

La vie de Lene reflète l'histoire allemande, tout comme le suggère la première image du film : une surface d'eau où se reflète un drapeau rouge frappé de la croix gammée. Lene rencontre Hans, son futur mari, en 1939 : une idylle amoureuse classique, suivie d'un mariage, puis le départ du jeune époux pour la campagne de Pologne. Anna, la fille, est conçue pendant un congé militaire et naît pendant une attaque aérienne, quand tout est sytématiquement détruit autour d'elle. Le retour des pères, aigris, vaincus, devenus étrangers à leurs familles, amène une nouvelle guerre au sein des foyers : les mères avaient quitté leurs cuisines, organisé des secours pendant les bombardements, parfois manipulé des canons de DCA, fait la chasse au ravitaillement, déblayé des ruines et participé à la reconstruction des villes. Le retour des pères leur ôte une intensité d'existence et certaines, comme Lene, se recroquevillent sur ellesmêmes, saisies par un sentiment d'inutilité, et sombrent dans l'alcoolisme. Lene, minée, tombe malade et une partie de ses muscles faciaux se paralysent. Elle est muette, folle, neurasthénique et repousse l'amour de sa fille de 9 ans. Puis se suicide au gaz.

La narration d'un destin privé est transformée par le génie artistique de Helma Sanders-Brahms en un miroir de l'histoire collective des Allemands. Se référant à Heinrich Heine, qui avait, dans un poème, comparé l'Allemagne à une « mère blême » (eine bleiche Mutter), et à Bertold Brecht, le dramaturge antinazi qui, depuis son exil californien, n'avait cessé de militer contre toutes les volontés alliées de « punir » son pays (en cela, il prenait le radical contre-pied de Thomas Mann, partisan d'une punition sévère). Helma Sanders-Brahms reprend à son compte ce désir de Brecht : pour elle comme pour lui, l'Allemagne est une pauvre mère, victime de fils ingrats, les nazis. Victime ensuite d'un viol par une puissance étrangère, l'Amérique : sur l'écran, le viol de Lene par deux GI's ivres. Helma SandersBrahms donne là une image de son pays ravagé, éclaté, fractionné, dont les familles, jadis havres de bonheur, sont détruites et dont les enfants errent affolés à la recherche de leurs parents.

L'Allemagne d'Adenauer qui sort de cette tragédie est décrite comme hyper-conventionnelle, irréelle, « kitsch ». Le nazi rénégat réussit dans cette société, comme cet Oncle Bertrand de Berlin, un opportuniste devenu « Président d'Église ». La cassure entre les discours officiels d'Adenauer, pleins de références grandiloquentes à l'éternité de l'Occident chrétien, est mise en exergue dans le film : tandis que la radio débite les belles paroles du Chancelier, des hommes ivres exécutent des cabrioles enfantines, titubent et tombent, grotesques, sur le sol. Cette scène veut nous montrer qu'il n'y a plus de vraie Allemagne, qu'il ne reste que des opportunistes méprisables, sans idéal autre que les hypocrites déclamations occidentalistes à la sauce catholique, ou que des prolos saoûls, incapables de se hisser au-dessus de leur vice.

Hans Jürgen Syberberg : marionnettes et irrationalisme

Tout autre est l'approche de Hans Jürgen Syberberg. La situation existentielle de l'Allemagne ne peut se symboliser par un récit, fût-il allégorique. Les reliquats épars de l'histoire allemande doivent être montrés comme les numéros d'un cirque : le film sur Hitler, qui rendit Syberberg si célèbre, est présenté par un « directeur de cirque » au visage maquillé de blanc vif. Le cinéaste a voulu par là provoquer une révolution dans l'art cinématographique. Et cette mutation doit se déclencher, pense Syberberg, par l'action de trois nouveautés qui bouleversent les habitudes de l'art cinématographique. D'abord, une provocation délibérée : Hitler n'est pas le sujet d'une œuvre documentaire et éducative mais d'un film poétique et imaginaire ; ensuite, par la trame du film qui n'est pas une story mais une succession de tableaux statiques (la juxtaposition de « numéros de cirque »), accompagnés de longs monologues de réflexions, selon les traditions inaugurées par Marguerite Duras et Alain Robbe-Grillet. Enfin, une affirmation philosophique qui postule que l'irrationalisme est le noyau profond de la plus authentique identité allemande, affirmation radicalement opposée à toute la philosophie officielle « rationaliste » (par antifascisme) de la RFA.

Syberberg, boycotté par les critiques allemands que son audace effrayait, voulait révolutionner les conventions du cinéma en exorcisant l'héritage de Hollywood. L'hollywoodisme « paraphrase » superficiellement le réel, pense Syberberg, et provoque ainsi une stagnation de l'art cinématographique. La tradition qu'il entend ressusciter est celle de Méliès et des cinémas muets russe et allemand, chez lesquels on découvre une tradition magique et non mimétique, qui crée un « espace réel de fiction », où, pour la durée du film, les lois de la logique sont mises entre parenthèses et où fantaisie, artifice et magie peuvent se mettre sans freins à nous fasciner. Faire présenter les « tableaux » par un maître de cérémonie en frac à basques, coiffé d'un haut-de-forme, permet une distanciation par rapport à la matière traitée. Le spectateur est ainsi toujours conscient de sa position de spectateur, comme dans le théâtre préconisé par Brecht. Les racines du cinéma doivent être recherchées dans le théâtre. L'accompagnement musical doit être présent, ce qui donne à l'art de Syberberg une connotation franchement wagnérienne. La combinaison des esthétiques de Wagner et de Brecht permet de saisir des éléments d'histoire par association de leitmotive répétés et non sur le mode « édificateur » et moralisant des conformistes. Les associations permettent à chaque spectateur de se façonner son propre jugement et d'extrapoler de manière créative, au-delà des slogans officiels préfabriqués.

Dénoncer un monde rigidifié

Les tableaux statiques, signaux de la post-histoire dans laquelle nous nous sommes enfoncés, cristallisent, gèlent et figent le réel pour symboliser un monde rigidifié, où l'histoire s'est arrêtée, où l'avenir est bouché (Syberberg est ici d'accord avec Fassbinder) et où les éléments morts et disloqués du passé sont (re)présentés par le maître de cérémonie. Rigidité et momification sont également exprimées par le masque pétrifié et sans vie des marionnettes qui jouent dans Hitter, ein Film aus Deutschland.

L'ostracisme pratiqué à l'encontre de Syberberg vient de sa défense de l'irrationalisme, fondement de l'identité allemande et matrice de toutes ses productions artistiques, musicales et littéraires. Sans irrationalisme, pas de Mozart, de Runge, de Caspar David Friedrich, de Schiller ou de Nietzsche. Le rationalisme de notre après-guerre, conçu pour servir de rempart contre cet irrationalisme qui a donné aussi Hitler, ne conduit qu'au culte du veau d'or et au néant culturel.

Malgré des approches différentes, venues tantôt de la gauche, tantôt de la droite, les cinéastes allemands prononcent tous un plaidoyer pour un retour à l'histoire et pour une transgression des tabous modernes et un réquisitoire impavide contre la RFA. Un souffle à la fois identitaire et révolutionnaire qui ne cadre pas du tout avec les discours sur la révolution que l'on entend dans les salons de l'Ouest...

Guy CLAES.

Anton KAES, Deutschlandbilder : Die Wiederkehr der Geschichte als Film, edition text + kritik, München, 1987, 264 S., DM 36.

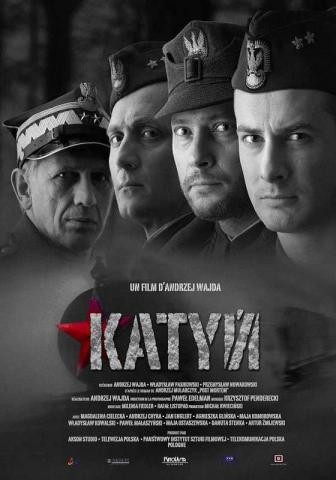

On projette donc le très beau film "Katyn" ce 14 avril (1) sur la chaîne franco-allemande Arte. Au-delà de l'œuvre de Wajda elle-même (2), de son scénario, tiré d'un roman mais aussi de l'expérience personnelle du cinéaste dans la Pologne communiste d'après-guerre, il faut considérer l'Histoire. Celle-ci accable non seulement Staline personnellement mais, d'une manière plus générale, le communisme international. Au premier rang en occident le parti le plus servile, le parti français, le parti de Maurice Thorez et de Jacques Duclos partage 100 % de la culpabilité de son maître. Et il faut y ajouter une circonstance aggravante. Car, après la Pologne en 1939, abandonnée par les radicaux-socialistes en charge à Paris de la conduite de la guerre, le sort de la France suivit en 1940.

On projette donc le très beau film "Katyn" ce 14 avril (1) sur la chaîne franco-allemande Arte. Au-delà de l'œuvre de Wajda elle-même (2), de son scénario, tiré d'un roman mais aussi de l'expérience personnelle du cinéaste dans la Pologne communiste d'après-guerre, il faut considérer l'Histoire. Celle-ci accable non seulement Staline personnellement mais, d'une manière plus générale, le communisme international. Au premier rang en occident le parti le plus servile, le parti français, le parti de Maurice Thorez et de Jacques Duclos partage 100 % de la culpabilité de son maître. Et il faut y ajouter une circonstance aggravante. Car, après la Pologne en 1939, abandonnée par les radicaux-socialistes en charge à Paris de la conduite de la guerre, le sort de la France suivit en 1940.

Sous ce titre paraîtra un ouvrage de l'auteur de ces lignes retraçant le contexte de la politique soviétique pendant toute l'entre deux guerres. Il comprend en annexe, et expliquant, plus de 80 documents diplomatiques, caractéristiques de cette alliance. Il sera en vente à partir du 15 mai au prix de 29 euros. Les lecteurs de L'Insolent peuvent y souscrire jusqu'au 30 avril au prix de 20 euros, soit en passant par la page spéciale sur le site des Éditions du Trident, soit en adressant directement un chèque de 20 euros aux Éditions du Trident 39 rue du Cherche Midi 75006 Paris. Tel 06 72 87 31 59.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

“Neuchâtel, 26 octobre.

“Neuchâtel, 26 octobre.

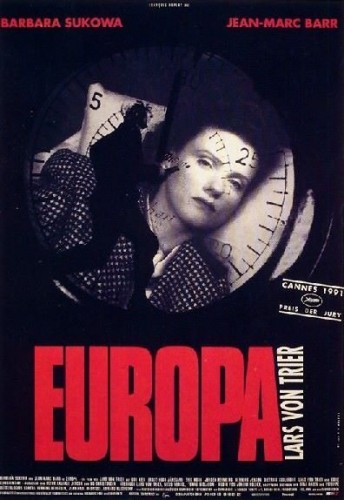

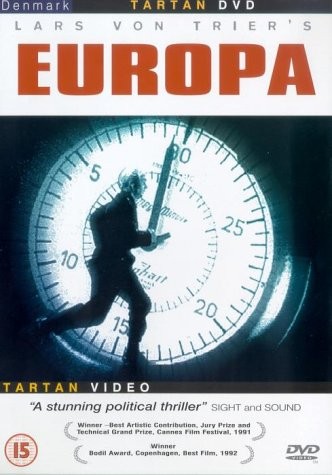

Europa is about a young American man born of German immigrants, Leopold Kessler, who travels to occupied Germany in late 1945, just a few months after the end of the war – an idealist and pacifist who, having deserted the American military during the conflict, now sees it as his mission to “show a little kindness to Germany” in order to “make the world a better place.”

Europa is about a young American man born of German immigrants, Leopold Kessler, who travels to occupied Germany in late 1945, just a few months after the end of the war – an idealist and pacifist who, having deserted the American military during the conflict, now sees it as his mission to “show a little kindness to Germany” in order to “make the world a better place.”

Making fun out of national stereotypes is not exactly standard comic fare

Making fun out of national stereotypes is not exactly standard comic fare

“

“

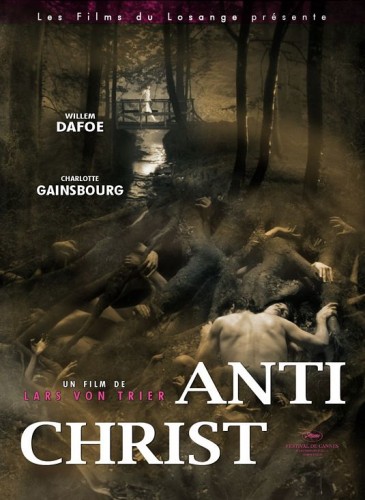

I will not explain the argument since you would only need to watch the movie, but, indeed, I can assure you it is not all about women’s evil. May be, it is more about the perception of evil in women that dominated Western culture during centuries –let us not forget that some time in history they were even claimed to lack a proper soul-. We have got clear examples of this in Eve, the first one, the one who succumbed to the Serpent in the Garden of Eden; in witches, burnt alive; in nuns and all the heretic tradition within the Western world. You have got plenty of bibliography about these that you can read on your own.

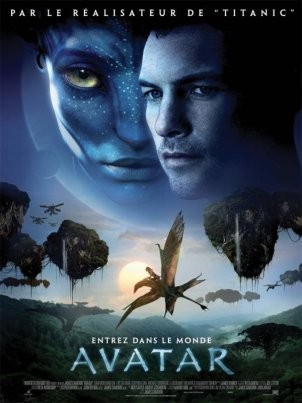

I will not explain the argument since you would only need to watch the movie, but, indeed, I can assure you it is not all about women’s evil. May be, it is more about the perception of evil in women that dominated Western culture during centuries –let us not forget that some time in history they were even claimed to lack a proper soul-. We have got clear examples of this in Eve, the first one, the one who succumbed to the Serpent in the Garden of Eden; in witches, burnt alive; in nuns and all the heretic tradition within the Western world. You have got plenty of bibliography about these that you can read on your own. Von Trier makes an extensive use of elements that appear in Fantasy literature but he sets them within a different context –this is similar to Avant-garde Literature-. One might claim he has not been able to reflect that clearly, but in our current market there is a very thin line separating ethics and reflection from endless benefits. Against the predominance of light stupidisation trough products like Avatar -that aims only at commercially viable ecology– only those with real talent are strong enough to survive. This way, there is not really a need for explanation; the story unfolds itself, this is what postmodernism is all about. But this one takes pleasure from aesthetics and thinks beyond catharsis –feeling good about being in the world-.

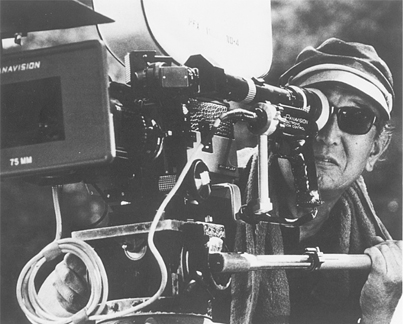

Von Trier makes an extensive use of elements that appear in Fantasy literature but he sets them within a different context –this is similar to Avant-garde Literature-. One might claim he has not been able to reflect that clearly, but in our current market there is a very thin line separating ethics and reflection from endless benefits. Against the predominance of light stupidisation trough products like Avatar -that aims only at commercially viable ecology– only those with real talent are strong enough to survive. This way, there is not really a need for explanation; the story unfolds itself, this is what postmodernism is all about. But this one takes pleasure from aesthetics and thinks beyond catharsis –feeling good about being in the world-. Akira Kurosawa è stato un uomo di cinema molto colto, uno di quelli che si sono ispirati ai geni della

Akira Kurosawa è stato un uomo di cinema molto colto, uno di quelli che si sono ispirati ai geni della

Jadis, le passé s'évanouissait dans les brumes des souvenirs, se voyait transformé et déformé par les imaginations. Aujourd'hui, le passé demeure, fixé sur les bobines de celluloïde, archivé dans les cinémathèques. Les films sont notre néo-mémoire ; ils ont démocratisé l'histoire qui, désormais, ne se stocke plus uniquement dans les crânes de quelques élites motrices, mais est directement accessible aux masses. La puissance de gérer, de dominer, de manipuler l'histoire appartient dorénavant à ceux qui produisent les images et les lèguent aux générations futures. Dès lors, une lutte s'engage – et nous le constatons dans nos journaux et l'observons sur nos écrans – pour l'organisation de la mémoire publique et collective. Quel sens va-t-on lui donner ? Avec quels critères va-t-on l'imprégner ?

Jadis, le passé s'évanouissait dans les brumes des souvenirs, se voyait transformé et déformé par les imaginations. Aujourd'hui, le passé demeure, fixé sur les bobines de celluloïde, archivé dans les cinémathèques. Les films sont notre néo-mémoire ; ils ont démocratisé l'histoire qui, désormais, ne se stocke plus uniquement dans les crânes de quelques élites motrices, mais est directement accessible aux masses. La puissance de gérer, de dominer, de manipuler l'histoire appartient dorénavant à ceux qui produisent les images et les lèguent aux générations futures. Dès lors, une lutte s'engage – et nous le constatons dans nos journaux et l'observons sur nos écrans – pour l'organisation de la mémoire publique et collective. Quel sens va-t-on lui donner ? Avec quels critères va-t-on l'imprégner ?

Filmbespreking: “Avatar”

Filmbespreking: “Avatar” Is een film die gaat over leven van de Franse zangeres Edith Piaf. Wiens echte naam Édith Giovanna Gassion is, maar onder de artiestennaam Piaf door het leven ging. Piaf betekent in het Nederlands ‘mus’. Een nukkige Parisienne, zeer gelovig en simpel, maar gezegend met een fabuleuze stem. De film schakelt tussen verschillende fasen van haar leven, wat soms even lastig is precies te snappen waar men nu is beland.

Is een film die gaat over leven van de Franse zangeres Edith Piaf. Wiens echte naam Édith Giovanna Gassion is, maar onder de artiestennaam Piaf door het leven ging. Piaf betekent in het Nederlands ‘mus’. Een nukkige Parisienne, zeer gelovig en simpel, maar gezegend met een fabuleuze stem. De film schakelt tussen verschillende fasen van haar leven, wat soms even lastig is precies te snappen waar men nu is beland.