mardi, 23 février 2016

Sept films à voir ou à revoir sur la Littérature russe

Sept films à voir ou à revoir sur la Littérature russe

Ex: http://cerclenonconforme.hautetfort.com

Il est un fait évident que la littérature russe compte parmi le fleuron des arts littéraires du Vieux continent, au sein duquel le 19ème siècle fait figure d'âge d'or. Jugeons-en plutôt à la lecture de l'école romantique d'Alexandre Pouchkine, Nicolas Gogol, Ivan Tourgueniev, Fiodor Dostoïevski, Léon Tolstoï ou Anton Tchekhov ! Avec moins de faste, le début du 20ème siècle poursuit un certain classicisme russe dont Maxime Gorki constitue la figure de proue. L'avènement du bolchévisme au pays du Grand Ours marque un coup d'arrêt dans la magnificence de la littérature russe, tant il est vrai que si le génie personnel de tout écrivain est la condition première à la réalisation d'un chef-d'œuvre, il est des climats politiques qui compliquent la tâche, voire la rendent impossible. Notons tout de même les œuvres de Boris Pasternak, Mikhaïl Boulgakov et Mikhaïl Cholokhov. Ces listes ne sont, bien entendu, pas exhaustives. Et comment pourrions-nous évoquer les lettres russes sans évoquer le caractère plus fiévreux des ouvrages d'Alexandre Soljenitsyne, bien sûr, dissident politiquement incorrect qui renvoie dos à dos le communisme et le capitalisme, mais également les théoriciens de l'anarchisme Mikhaïl Bakounine et Pierre Kropotkine ? Et plus proche de nous, l'inclassable écrivain franco-russe, fondateur du parti national-bolchévique, Edouard Limonov. Si comme toutes les littératures nationales, les lettres moscovite et saint-pétersbourgeoise furent très influencées par la littérature occidentale, plus particulièrement française, elles n'en conservent pas moins des aspects particuliers. Plus que tout autre, la littérature russe est certainement déterminée géographiquement et psychologiquement par l'âme de sa Nation, dont la construction identitaire est marquée par la violence des soubresauts de son Histoire récente. Le lecteur profane en Histoire russe pourrait rapidement se heurter à une littérature absconse qui lui ferait manquer la dimension charnelle de l'œuvre. Littérature pessimiste, voire nihiliste, dans laquelle les cicatrices et fractures morales de l'individu constituent des aliénations, littérature dense faisant figurer de nombreux protagonistes, acteurs d'une intrigue diffuse et compliquée, la littérature russe est très difficilement transposable sur une pellicule. Il est d'ailleurs à noter que ce ne sont pas des cinéastes russes qui s'attaquèrent aux monuments littéraires de leur patrie éternelle. Adapter, c'est trahir dit-on ! Cela vaut certainement encore plus pour Dostoïevski et Tolstoï ! Aussi, qui est exégète de ces œuvres littéraires, dont la force et la beauté demeurent un apport incommensurable à l'identité européenne, sera déçu des films présentés. Pour les autres, il s'agira d'une formidable découverte.

Anna Karénine

Film américain de Clarence Brown (1935)

La Russie tsariste dans la seconde moitié du 19ème siècle. Anna Karénine est l'épouse d'un sombre et despotique noble, membre du gouvernement. Prisonnière d'un mariage de raison, l'épouse délaissée n'a jamais vraiment manifesté de sentiment amoureux pour son mari, à la différence de son jeune garçon Sergeï qui constitue son seul rayon de soleil. L'amour qu'elle porte à son enfant ne lui suffit néanmoins pas. Sa vie faite de convenances bourgeoises et de respectabilité sociale l'ennuie terriblement. Aussi, lors d'un voyage à Moscou, succombe-t-elle aux avances du colonel Comte Vronsky, jeune cavalier impétueux. Vronsky ne tarde pas à suivre Anna à Saint-Pétersbourg. L'idylle adultère est bientôt découverte et provoque un scandale. Anna est chassée de la maison sans possibilité de revoir son enfant. Elle va tout perdre, d'autant plus que si le Comte est un fougueux prétendant, sa véritable maîtresse est l'armée du Tsar...

Fait rare ! Greta Garbo interprètera à deux reprises l'héroïne du roman éponyme de Tolstoï, après une première adaptation muette d'Edmund Goulding sept années plus tôt. La présente adaptation de Brown est soignée mais la retranscription hollywoodienne de la Russie tsariste a un côté "image d'Epinal" très décevant. On n'y croit guère ! On ne peut que se rendre compte qu'adapter à l'écran la richesse d'une œuvre dense de plusieurs centaines de pages est une gageure. Egalement, peut-être la volonté du réalisateur était-elle justement de gommer le caractère russe de l'œuvre de Tolstoï afin de délivrer une vision plus universelle de cet amour interdit. A cet égard, la mise en scène est impeccable, de même que les décors et les costumes. Garbo et Fredric March ont un jeu impeccable.

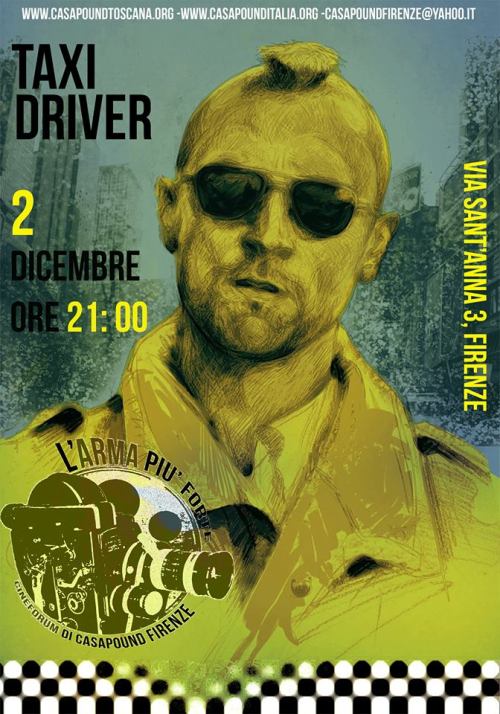

LE DOCTEUR JIVAGO

Titre original : Docteur Zhivago

Film américain de David Lean (1965)

Moscou en 1914, peu avant que la Première Guerre mondiale n'achemine la Russie tout droit vers la Révolution bolchévique. Le docteur Youri Jivago est un médecin idéaliste dont la véritable passion demeure la poésie. Jivago mène une vie paisible auprès de son épouse Tonya et leur fils Sacha, que vient bientôt bousculer Lara, fiancée à un activiste révolutionnaire, dont le médecin tombe immédiatement amoureux. Lorsqu'éclate la guerre, Jivago est enrôlé malgré lui dans l'armée russe et opère sans relâche les blessés sur le front. Sa route croise de nouveau celle de Lara devenue infirmière. D'un commun accord, ils se refusent mutuellement cette histoire sans lendemain. Après la Révolution d'octobre 1917, la vie devient précaire dans la capitale moscovite. Jivago se réfugie dans sa propriété de l'Oural avec sa famille afin d'échapper à la faim, au froid et à une terrible épidémie de typhus qui ravage le pays...

Film librement inspiré du roman éponyme de Pasternak et là aussi, un pavé de plusieurs centaines de pages à porter à l'écran. Lean s'en sort à merveille au cours de ces trois heures-et-demi, en retranscrivant magnifiquement l'épopée de ce jeune médecin en quête de vérité dans le tumulte de l'aube du vingtième siècle. Aussi, à la différence du livre, le film est-il recentré sur les protagonistes principaux. Pour que celui-ci soit à la hauteur, les producteurs y ont mis les moyens et ne se sont pas montrés avares en dépenses ! Le film, longtemps censuré au pays des Soviets, reprend bien évidemment avec la plus grande fidélité la critique du régime bolchévique par Pasternak. Ce qui n'est pas très surprenant non plus, concernant une production américaine en pleine période de guerre froide. Omar Sharif est convaincant. Une fresque grandiose qui a quand même un peu vieilli.

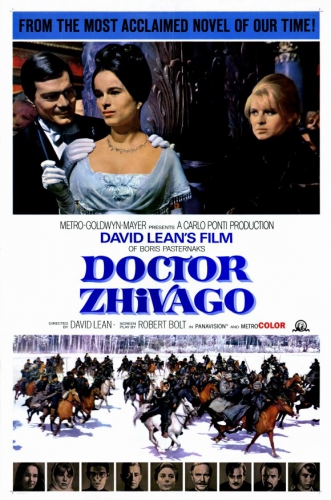

LE JOUEUR

Film franco-italien de Claude Autant-Lara (1958)

En 1867, Le général Comte russe Alexandre Vladimir Zagorianski prend du bon temps avec sa famille à Baden-Baden en attendant le décès de sa riche tante Antonina dont il espère l'héritage prochain. Le général est accompagné d'Alexeï Ivanovich, précepteur des enfants. L'oisiveté à laquelle la vie du général est toute dévouée le pousse à s'abandonner dans les bras de Blanche, habile intrigante. Quant à sa fille Pauline, elle est la maîtresse du marquis des Grieux, un riche aristocrate français qui entretient toute la famille du général tant qu'Antonia n'a pas expiré. Et la tante ne semble guère pressée de trépasser. Certes en fauteuil roulant, elle rend visite à son général de neveu en Allemagne. Ivanovich, qui avait prévu de retourner à Moscou après qu'il se soit fait éconduire par Pauline, change ses plans à l'arrivée de la riche tante qui le prend à son service. Antonia épouse le démon du jeu et a tôt fait de dilapider la fortune qui faisait tant l'espoir de Zagorianski...

Autant-Lara ne tire pas son meilleur film de sa libre adaptation du roman éponyme de Dostoïevski. Loin de là... Et Liselotte Pulver, Gérard Philipe et Bernard Blier ne sont pas au mieux de leur forme. Certes, Dostoïevski n'est pas l'auteur dont les personnages sont les plus simples à camper... Le film d'Autant-Lara est plus proche du Vaudeville que de la restitution de l'hédonisme russe en Allemagne. Néanmoins, cette fantasque description de l'univers du jeu au 19ème siècle, parfois trop caricaturale et mièvre, revêt des caractères plaisants bien rendus par les décors et l'atmosphère des villes d'eaux du duché de Bade. A réserver aux inconditionnels du réalisateur de La Traversée de Paris.

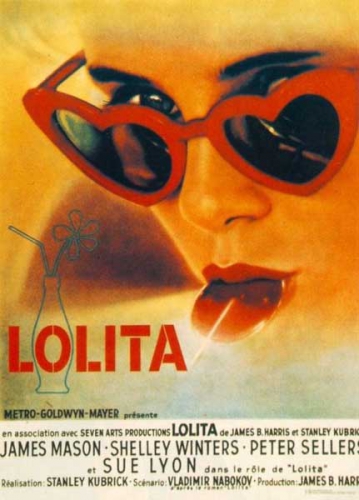

LOLITA

Film anglais de Stanley Kubrick (1962)

C'est l'été dans la petite ville de Ramslade dans le New Hampshire. Humbert Humbert est un séduisant professeur de littérature française récemment divorcé qui cherche une chambre à louer dans la ville. C'est dans la demeure de Charlotte Haze, veuve érudite en mal d'amour, qu'il trouvera son bonheur, surtout après avoir entraperçu Dolorès, quatorze ans, surnommée Lolita, la charmante fille de Charlotte. La propriétaire essaye par tous les moyens de s'attirer les faveurs du professeur bien plus tenté par le charme de la juvénile Lolita. Afin de pouvoir continuer à demeurer chez les Haze à l'issue de sa location, et ainsi à proximité de l'adolescente , Humbert n'hésite pas une seconde et épouse la mère. Le bonheur marial est de courte durée. Charlotte ne tarde pas à démasquer les véritables intentions de son nouveau mari...

Réalisation très librement inspirée du roman éponyme de Vladimir Nabokov qui ne fit pas l'unanimité. Certains allèrent jusqu'à hurler à la trahison de l'œuvre du moins russe des écrivains russes, dont la famille s'exila après la Révolution d'octobre 1917. Il est vrai que le film de Kubrick, qui n'a pourtant jamais craint d'érotiser son œuvre, contient une sensualité moindre que le roman. Il est vrai aussi que la censure exerçait encore de nombreuses contraintes à l'orée de la décennie 1960. Kubrick avait d'ailleurs déclaré, après avoir dû couper plusieurs scènes, qu'il aurait préféré ne pas tourner cette adaptation critique de la libéralisation sexuelle outre-Atlantique. La jeune Sue Lyon est merveilleuse, de même que James Manson. Il est difficile de juger si Lolita figure parmi les meilleurs Kubrick. Mais ça reste du grand Kubrick !

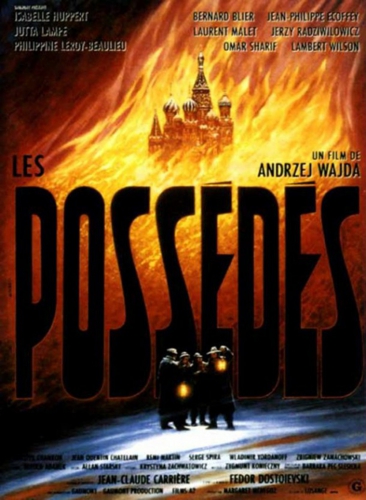

LES POSSEDES

Film français d'Andrzej Wajda (1987)

Vers 1870, dans une ville de province de l'Empire russe, un group d'activistes révolutionnaires tente de déstabiliser la Sainte-Russie. Aux réunions, grèves et diffusions de tracts, succède bientôt l'action clandestine. Conduits par l'exalté fils d'un professeur humaniste, Pierre Verkhovenski, la cellule nihiliste confie la direction du mouvement à Nicolas Stavroguine, de condition aristocrate, mais cynique et désabusé. Fanatique et charismatique, Stavroguine exerce un pouvoir sans pitié sur le groupe. Aussi, ordonne-t-il l'exécution de Chatov, ouvrier honnête qui manifestait ses distances avec la bande au sein de laquelle les tensions s'exacerbent. Verkhovenski intrigue afin que Kirilov, un athée mystique, endosse le crime. Kirilov est contraint au suicide...

Au risque de se répéter, une nouvelle fois, le film est inférieur au roman, bien que la présente réalisation de Wajda conserve un intérêt majeur et de splendides images. Le fond de l'intrigue est survolé et perd, ainsi, en intensité, au regard des centaines de pages de l'œuvre de Dostoïevski, mais comment pourrait-il en être autrement ? Si Omar Sharif incarne, de nouveau et de manière satisfaisante, un héros de la littérature russe, les personnages du film pourront être perçus comme excessifs à l'exception de Sjatov, révolutionnaire qui garde raison plus que les autres. Wajda semble assez peu à l'aise dans sa représentation de l'esprit révolutionnaire qu'il apparente trop vulgairement à une soif de violence gratuite. A voir quand même !

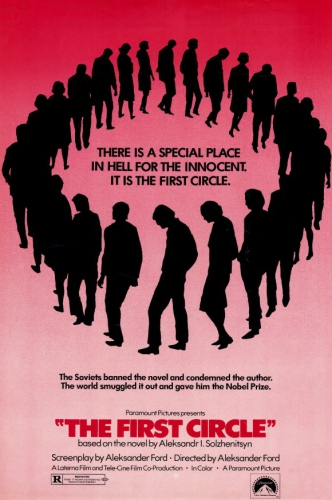

LE PREMIER CERCLE

Titre original : The First circle

Film américain d'Aleksander Ford (1972)

En 1949, un jeune diplomate découvre, à la lecture d'un dossier, l'arrestation imminente d'un grand médecin. Le diplomate prend la décision de prévenir anonymement le futur embastillé, ne se doutant que des oreilles mal intentionnées enregistrent la conversation téléphonique. La mise sur écoute n'est pas encore jugée suffisamment au point par les services secrets. Nombre de savants s'ingénient ainsi à perfectionner le système dans une charachka, laboratoire de travail forcé, de la banlieue moscovite. L'un des ingénieurs, conscient que l'écoute téléphonique est une arme coercitive précieuse pour les services secrets, entreprend de détruire sa création perfectionnée. Ce sabotage n'a d'autre issue que sa déportation en Sibérie. De même pour le diplomate bientôt identifié qui avait tenté de sauver la liberté du médecin. Parmi tout l'appareil répressif communiste, les laboratoires dans lesquels sont mis au point les armes de répression massive constituent le premier cercle de l'Enfer stalinien.

Il est surprenant que ce soit le cinéaste polonais rouge Ford qui se soit porté volontaire pour adapter à l'écran un roman de Soljenitsyne... Certainement revenu de ses illusions sur la nature du régime stalinien, Ford livre un plaidoyer en faveur de la liberté et de la dignité humaines. Soucieux d'une recherche esthétique, celle-ci n'est pourtant pas toujours réussie mais livre des passages intéressants que magnifie le noir et blanc. Le film est malheureusement tombé dans les oubliettes du Septième art. Quant au titre du récit éponyme et largement autobiographique de Soljenitsyne, il fait référence aux neufs cercles de l'Enfer de la Divine comédie de Dante Alighieri.

UN DIEU REBELLE

Titre original : Es ist nicht leicht ein Gott zu sein

Film germano-franco-russe de Peter Fleischmann (1989)

La Terre dans un futur loin de plusieurs siècles. Les Terriens sont parvenus à une parfaite maîtrise de leurs émotions afin de vivre dans une paix perpétuelle. A des fins d'étude, une équipe de chercheurs est envoyée en observation d'une autre civilisation humaine sur une lointaine planète. Afin de ne pas dévoiler leur présence, seul Richard est choisi parmi les siens pour aller à la rencontre des habitants. Un seul impératif guide son action : la non-ingérence dans les affaires autochtones. Le temps passe et Richard ne donne plus aucun signe de vie au reste de l'équipage demeuré dans le vaisseau spatial. Inquiet, Alan fait à son tour le voyage vers la planète semblable à la Terre mais sur laquelle les mœurs des habitants, brutales et cruelles, et la technologie accusent plusieurs siècles de retard...

Délaissons quelque peu l'univers de la littérature classique russe pour nous intéresser à un chef-d'œuvre méconnu de la littérature de science-fiction. Le présent film est une adaptation du roman Il est difficile d'être un Dieu des frères Arcadi et Boris Strougatski et est supérieur à la seconde adaptation éponyme d'Alexeï Guerman. Le présent film ne manque pas d'être subversif et peut être considéré comme une vive critique du soviétisme et, dans une perspective plus large, de la barbarie de la soumission à autrui qu'exerce la violence. La mise en scène est néanmoins faible, les cadrages serrés curieux au regard de l'immensité du décor et les effets spéciaux peu travaillés. Et pourtant ! Voilà un petit bijou que les passionnés de science-fiction considéreront comme culte. Les plus rationnels des spectateurs pourraient, quant à eux, s'endormir longtemps avant la fin. Tourné au Tadjikistan pour les décors naturels, il offre, en outre, de splendides paysages.

Virgile / C.N.C.

Note du C.N.C.: Toute reproduction éventuelle de ce contenu doit mentionner la source.

14:53 Publié dans Cinéma, Film, Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : russie, film, cinéma, 7ème art, littérature, lettres, lettres russes, littérature russe |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 24 décembre 2015

Comment l’Occident est passé de l’Iliade à Star Wars?

Une semaine après sa sortie aux États-Unis d’Amérique, le septième volet de la saga Star Wars – Le réveil de la Force – vient de battre un record de bénéfices, atteignant 238 millions de dollars. Quant au public français, l’intervalle de quelques jours qui sépara la sortie du film aux États-Unis et en France semble avoir été vécu comme un supplice, à en croire le Figaro qui titrait le 15 décembre : « En France, le monde de la culture s’impatiente. »

Jean Raspail et Renaud Camus ont le mérite d’avoir alerté le peuple français sur le Grand Remplacement orchestré par étapes, dans le plus grand silence. Mais ce remplacement n’est-il que démographique ? N’y a-t-il pas aussi une véritable substitution dans les fondements de notre culture ? Pour ce remplacement culturel, ce n’est pas dans les sables brûlants d’Arabie mais vers les tours métalliques de l’Oncle Sam qu’il faut porter le regard pour y trouver les réponses.

Qu’est-ce que la culture sinon un ensemble de mœurs, de techniques et de savoirs, cimentant l’unité d’un peuple, ayant pour fondement une tradition orale ou écrite ? Les textes dits « fondateurs » propres à chaque civilisation en ont à bien des égards façonné les mentalités. Que serait l’univers judaïque sans la Torah, le monde chinois sans Confucius ou l’Occident sans l’épopée homérique, la vaste littérature chrétienne et les nombreux récits d’aventures celto-germaniques qui en ont façonné l’esprit tout au long des siècles ?

Mais en 2015, Achille et le roi Arthur ont déserté nos esprits et nos discussions, sauf lorsqu’ils sont accaparés par des réalisateurs pour des films de qualité médiocre portant les mêmes messages lénifiants de tolérance et d’irénisme.

À la place, des allusions à Han Solo, Voldemort ou Gollum affleurent dans les conversations, quand ces personnages ne sont pas pris pour modèles par les jeunes générations. Détail révélateur : on parle de « saga » ou d’« épopée » pour désigner ces séries qui durent parfois pendant des décennies et engrangent des milliards de bénéfices.

ERTV (dont certes on peut avoir beaucoup à redire) a réalisé un reportage sur ce phénomène Star Wars, en interrogeant ces milliers de Français massés devant les cinémas pour espérer une place ne serait-ce qu’à la séance de 22 heures. L’effervescence était à son comble, les réactions étant quasi orgasmiques. Mais à la question « Pourquoi êtes-vous fan de Star Wars ? », cette joie frénétique laissait place au silence gêné ou, pire, aux poncifs sans cesse répétés : « Parce que c’est culte », dit l’un ; « C’est fondateur de notre culture », clame l’autre ; « Révisez vos classiques », affirme un troisième…

La culture est mobile, me direz-vous. Certes, l’art ne peut vaticiner indéfiniment entre Antiquité et Renaissance, la nouveauté est vitale pour l’esprit humain. Mais je ne conçois pas qu’Homère et Chrétien de Troyes s’effacent honteusement devant Rowling, Tolkien ou E. L. James au seul prétexte que « les temps changent ».

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Cinéma, Film, Réflexions personnelles | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, star xars, cinéma, film, occident |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 17 décembre 2015

Sept films à voir ou à revoir sur les Nations sans Etat

Sept films à voir ou à revoir sur les Nations sans Etat

Ex: http://cerclenonconforme.hautetfort.com

Depuis la fin de la période de décolonisation amorcée au lendemain de la Seconde Guerre mondiale jusqu'au milieu des années 1970, les notions d'éternité et d'intangibilité des frontières nationales sont durablement inscrites dans la représentation mentale collective. Or, ces derniers mois, les aspirations à l'indépendance de l'Ecosse et de la Catalogne bouleversent ces certitudes qui n'avaient pas été aussi ébranlées, au sein des Etats piliers de l'Union européenne, depuis de nombreuses décennies. De nombreux Etats européens ne masquent pas leurs craintes que ces exemples ne créent un lourd précédent. En réalité, qu'est-ce qu'une frontière continentale si ce n'est une limite issue d'un traité de guerre ou d'une union par mariage ? Ainsi, les luttes indépendantistes constituent-elles un légitime moteur de l'Histoire. Depuis la dissolution de l'ancien bloc soviétique au début de la décennie 1990, qui a favorisé l'accession ou la ré-accession à l'indépendance de nombre d'anciennes républiques soviétiques, ce ne sont pas moins de six pays qui sont parvenus à l'indépendance ces vingt dernières années : de l'Erythrée en 1993 au Soudan du Sud en 2011, en passant par le micro-Etat du Pacifique des Palaos, le Timor Oriental et le Monténégro. Il nous sera permis d'être plus circonspect concernant le sixième cas. Car si de nombreux Etats européens ne masquent pas leurs craintes de voir leurs frontières remises en cause, ces Etats-dit-Nations, si prompts à se crisper sur leur intégrité territoriale avaient su se montrer plus favorables, en 2008, à soutenir l'indépendance de l'Etat-mafieux islamiste du Kosovo-et-Métochie, au détriment du caractère de berceau originel que représente le Kosovo pour une Nation serbe qui n'avait pas voulu se plier aux injonctions du Nouvel Ordre mondial... Mauvais apprentis sorciers, les arroseurs sont aujourd'hui les arrosés. "Aujourd'hui la Serbie, demain la Seine-Saint-Denis, un drapeau frappé d'un croissant flottera sur Paris".... La chanson prophétique Paris-Belgrade du groupe de rock In Memoriam fait dramatiquement écho aux récents événements survenus dans la très jacobine Nation française.

LA BATAILLE DE CULLODEN

Titre original : The Battle of Culloden

Film anglais de Peter Watkins (1964)

16 avril 1746, à Culloden, des membres des différents clans rebelles écossais des Highlands, menés par le Prince Charles Edouard Stuart, font face aux troupes anglaises du Roi George II de Grande-Bretagne, que commande le Duc de Cumberland. Il ne faut pas plus d'une heure pour que le destin de la bataille soit scellé. Les Ecossais, mal organisés, sont mis en pièce par l'armée royale mieux équipée. Le combat terminé, la pacification du gouvernement britannique est d'une férocité sans nom. L'objectif avoué est de totalement annihiler le système clanique et, ainsi, de prévenir toute nouvelle rébellion dans les Hautes terres. Ils seront plus de deux mille Ecossais à périr dans la lande marécageuse ce jour-là...

Watkins a curieusement opté pour un montage singulier. Aussi, le film se présente-t-il comme un documentaire d'actualités tourné caméra à l'épaule. Le réalisateur se balade donc sur le champ de bataille et interviewe les combattants çà-et-là sans manquer pas de commenter le déroulé de la bataille en voix off. Choix risqué mais, ô combien, magistralement réussi ! Tourné avec des comédiens amateurs et un maigre budget, on est loin de la grande production peu avare en mélodrame. Et voilà tout le charme de Watkins, le drame brut l'emporte sur le pathos, finalement assez anachronique. Culloden, c'est un peu un Braveheart réussi ! Un chef-d'œuvre !

BRAVEHEART

Film américain de Mel Gibson (1995)

En cette fin de treizième siècle, l'Ecosse est occupée par les troupes d'Edouard 1er d'Angleterre. Rien ne distingue un certain William Wallace de ses frères de clan lorsque son père et son frère meurent opprimés. Bien au contraire, Wallace souhaite avoir le moins d'ennuis possibles avec la soldatesque anglaise et s'imagine parfaitement en modeste paysan et époux de son amie d'enfance, Murron MacClannough. C'est en secret que les amoureux se marient afin d'épargner à la belle de subir le droit de cuissage édicté par la couronne anglaise. Mais Murron est bientôt violentée par un soldat anglais, provoquant la fureur de Wallace. La jeune femme est étranglée devant ses yeux. Wallace ne pense plus qu'à se venger. La garnison britannique du village est massacrée, première bataille d'une longue série de reconquête des clans écossais à l'assaut des Highlands...

Oui, Braveheart est un beau film ! Oui, les scènes de bataille sont fabuleuses ! Oui, le personnage de Wallace, imaginé et interprété par Gibson, ferait se soulever n'importe quel militant et s'enhardir du courage nécessaire lorsqu'il n'y a plus d'autre solution que le combat. Oui, Wallace est un héros nationaliste qui ne laisse pas indifférent. Oui, Gibson maîtrise toutes les ficelles du Septième art dès son deuxième long métrage. Oui, il est normal que vous ayez irrésistiblement eu une furieuse envie de casser la figure de Darren, brave étudiant londonien en Erasmus, qui vous tient lieu de pourtant si amical voisin. Oui, oui, oui et pourtant... Braveheart ne parvient pas au niveau de la réalisation de Watkins. La faute à un pathos romantique trop exacerbé et une idylle absolument mal venue avec Isabelle de France, bru du Roi Edouard 1er. Il est néanmoins impensable de ne pas le voir et l'apprécier.

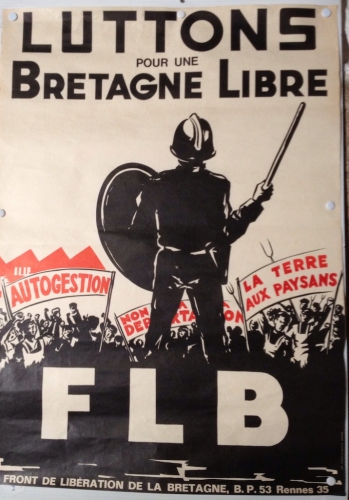

FLB

Documentaire français de Hubert Béasse (2013)

En quatorze années d'existence, de 1966 à 1980, le Front de Libération de la Bretagne a commis pas moins de deux centaines d'attentats. Par tous les moyens, les F.L.B. entreprennent de défaire l'annexion de la Bretagne à la France, héritée du mariage de la Duchesse Anne, alors seulement âgée de douze ans, et du Roi de France Charles VIII. Les nombreux attentats visent l'ensemble des pouvoirs régaliens et symboliques de la France. Le plasticage de l'antenne de retransmission télévisée de Roc'h Trédudon, privant la Bretagne de télévision pendant plus d'un mois, et le dynamitage de la Galerie des glaces du château de Versailles comptent parmi les actions les plus spectaculaires menées par les mouvements indépendantistes en France. Evidemment, la répression ne tarde pas à frapper l'Emsav...

Divisé en deux parties, Les Années De Gaulle et Les Années Giscard, le remarquable documentaire de Béasse donne la parole à nombre d'anciens F.L.B., dont le témoignage est assorti de nombreux documents inédits. Provenant d'horizons politiques, parfois les plus opposés, l'extension du F.L.B. ne pouvait que rimer avec scission. S'ouvrant aux thèses socio-économiques anticapitalistes, l'Armée Révolutionnaire Bretonne entend marier ses initiales au sigle F.L.B. et lutter pour une Bretagne plus progressiste. Béasse, par bonheur, entend tendre le micro à toutes les tendances des F.L.B., et ce, avec une objectivité appréciable dans le traitement des témoignages. Les pendules sont remises à l'heure pour ceux qui ont la mémoire courte ou la dent dure sur la réalité du mouvement breton. Parfaitement intéressantes que ces deux heures documentaires.

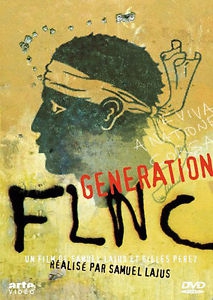

GENERATION FLNC

Documentaire français de Samuel Lajus (2004)

Il est dit que l'omerta règne en Corse. Pas dans ce passionnant et poignant documentaire en tout cas. De nombreuses images d'archives enrichissent les témoignages d'une trentaine d'ex-militants quinquagénaires du Front, de représentants du nationalisme corse mais également de hautes personnalités, tel le commissaire Robert Broussard, Jean-Louis Debré ou Charles Pasqua. La langue de bois n'est ainsi pas de mise, y compris sur les sujets les plus sensibles, des règlements de compte entre partisans de la même cause aux négociations secrètes entre les clandestins et l'Etat, mais aussi sur la dérive mafieuse de certaines factions. Finalement, ce sont les représentants de l'Etat qui en disent le moins ; tant il est vrai qu'ils n'ont pas les fesses complètement propres sur ces sujets. Deux années de tournage pour achever ce document, extraordinaire de décorticage d'un sentiment identitaire. Indispensable pour qui s'intéresse au sujet.

L'ORDRE ET LA MORALE

Film français de Mathieu Kassovitz (2011)

1988, loin de l'hexagone, sur l'île kanake d'Ouvéa, quatre gendarmes sont abattus dans l'assaut de leur caserne et vingt-sept autres retenus par des membres du mouvement indépendantiste du Front de Libération National Kanak et Socialiste. La situation se dégradait depuis de nombreux mois. Trois cents militaires sont dépêchés sur l'île calédonienne pour libérer les otages. Philippe Legorjus, patron de l'élite des gendarmes d'intervention, et Alphonse Dianou, leader des preneurs d'otages, partagent bien des valeurs communes, l'honneur surtout. Legorjus sent qu'il peut maîtriser la situation sans effusion de sang mais la France est alors à deux jours du premier tour des élections présidentielles. Dans le combat qui opposera Jacques Chirac et François Mitterrand en pleine cohabitation, la morale ne semble pas être la première préoccupation des deux candidats.

Tiré de l'ouvrage La Morale et l'action de Legorjus, le film ne manqua pas de faire scandale. Film militant pro-indépendantiste selon les partisans de la vérité d'Etat, film inutile pour de nombreux Kanaks estimant la réouverture des cicatrices inutile. C'est certainement Legorjus qui constitue la source la plus fiable pour expliquer ce bain de sang. Manipulation des faits pour de basses considérations électives, réalité d'un néo-colonialisme français, fortes rivalités entre de hauts gradés, la prise d'otages de la grotte ne pouvait connaître d'issue sereine. Les exécutions sommaires de militants indépendantistes fait prisonniers sont là pour le rappeler. Parfois manichéen dans sa caricature des militaires français, le film de Kassovitz demeure néanmoins extrêmement convaincant. A voir absolument !

15 FEVRIER 1839

Film québécois de Pierre Falardeau (2001)

14 février 1839, sous le régne de la Reine Victoria, deux héros québécois de la lutte pour l'indépendance, Marie-Thomas Chevalier de Lorimier et Charles Hindelang, apprennent que la sentence de mort par pendaison sera appliquée le lendemain. Voilà deux années que ces hommes comptent parmi huit cents détenus emprisonnés à Montréal dans des conditions dégradantes après l'échec de l'insurrection de 1837, dont une centaine a été condamnée à mort par les autorités colonialistes anglaises. Entourés de leurs compagnons d'infortune, vingt-quatre heures les séparent de leur funèbre destin. De vagues sursauts d'espoir affrontent la peur et le doute. Une seule chose est sûre, affronter la mort sera leur dernier combat. Et ils ne regrettent rien...

Malgré une parenté historique et linguistique évidentes, que connaît-on aujourd'hui du Québec en France et de son aspiration à la liberté ? Inspiré de faits réels, Falardeau rompt avec sa filmographie satirique et a à cœur de rendre hommage aux luttes indépendantistes qui ont enflammé le pays québécois au 19ème siècle. Le réalisateur livre un huis-clos sombre de toute beauté. D'un parti pris indépendantiste évident, le film a légitimement été fortement égratigné par la critique anglophone dénonçant un déferlement de haine antibritannique. Quelques approximations historiques ne nuisent pas à un ensemble prodigieux.

SALVATORE GIULIANO

Film italien de Francesco Rosi (1961)

5 Juillet 1950, le corps criblé de balles du bandit indépendantiste sicilien Salvatore Giuliano est découvert dans la cour d'une maison du village de Castelvetrano. Si l'homme était traqué par la police et l'armée italiennes, il semblerait qu'il ait été retrouvé avant eux. Le constat du décès est dressé par un commissaire tandis que les journalistes sont à l'affût du moindre renseignement. La mort achève une existence intrépide commencée en 1945 lorsque Giuliano s'engage dans la lutte violente, avec l'appui de la Mafia, pour l'indépendance de son île. Le 1er mai 1947, il avait été notamment impliqué dans l'assassinat de militants socialistes. Son corps est bientôt exposé dans sa commune natale de Montelepre, où sa mère et les habitants viennent se recueillir avec une dévotion non simulée. Tous les regards convergent alors vers Gaspare Pisciotta, lieutenant de Giuliano, que tous soupçonnent de l'avoir trahi et assassiné...

Film subversif et engagé à plus d'un titre ! Rosi utilise un curieux procédé scénographique pour évoquer la vie de ce curieux personnage historique sicilien, moitié bandit indépendantiste, moitié Robin des Bois dont le souhait était de voler les riches pour donner aux pauvres et arracher l'île à la domination italienne pour en faire le quarante-neuvième Etat d'Amérique. Ainsi, le récit anarchique de Rosi parvient-il à ne pas être brouillon sans aucun ordre chronologique. Autre point fort, Rosi est l'un des premiers à dénoncer les rapports étroits de la Cosa nostra avec le pouvoir politique sicilien. Enfin, le réalisateur n'a pas hésité à faire appel à des acteurs non-professionnels, renforçant le caractère authentique de l'œuvre. Un grand film politique par l'un des maîtres du cinéma italien.

Virgile / C.N.C.

Note du C.N.C.: Toute reproduction éventuelle de ce contenu doit mentionner la source.

00:05 Publié dans Cinéma, Film | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : cinéma, film, 7ème art, peuples sans état, écosse, nationalisme écossais, indépendantisme écossais, bretagne, nationalisme breton, corse, indépendantisme corse, québec |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 12 décembre 2015

CHEYENNE-MARIE CARRON: Cinéaste de l’insoumission

CHEYENNE-MARIE CARRON: Cinéaste de l’insoumission

Pierre-Emile BlaironEx: http://metamag.fr

La bataille des régionales aura pour enjeu important la question des subventions attribuées au secteur culturel, là où la droite, suivie de la gauche, sont intervenues pour largement subventionner nombre d’associations dont la vocation consiste à détruire les structures traditionnelles, culturelles et artistiques de notre pays au détriment de créateurs, artistes, écrivains, cinéastes, revues, groupements de préservation de nos racines et traditions qui constituent les fondements même de notre avenir. Cheyenne-Marie Carron est, parmi de nombreux autres, l’exemple vivant de cette injustice et de ces dysfonctionnements.

La bataille des régionales aura pour enjeu important la question des subventions attribuées au secteur culturel, là où la droite, suivie de la gauche, sont intervenues pour largement subventionner nombre d’associations dont la vocation consiste à détruire les structures traditionnelles, culturelles et artistiques de notre pays au détriment de créateurs, artistes, écrivains, cinéastes, revues, groupements de préservation de nos racines et traditions qui constituent les fondements même de notre avenir. Cheyenne-Marie Carron est, parmi de nombreux autres, l’exemple vivant de cette injustice et de ces dysfonctionnements.

Quels sont les éléments que vous aimeriez apporter, après une certaine expérience, à votre façon de travailler et de concevoir les films, pour progresser dans votre métier ?

Quels sont les éléments que vous aimeriez apporter, après une certaine expérience, à votre façon de travailler et de concevoir les films, pour progresser dans votre métier ?

00:05 Publié dans Cinéma, Film | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : cheyenne marie carron, cinéma, film, france |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 16 novembre 2015

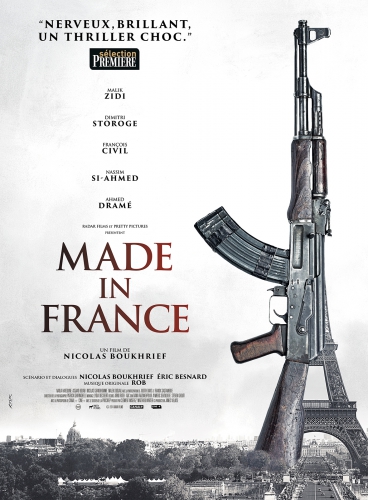

ATTENTATS "Made in France" : l’affiche du film retirée, sa sortie repoussée

ATTENTATS "Made in France" : l’affiche du film retirée, sa sortie repoussée

Ex: http://sans-langue-de-bois.eklablog.fr

ATTENTATS "Made in France" : l’affiche du film retirée, sa sortie repoussée. « Une vague d’attentats va secouer toute la France. » Lorsqu’on la visionne au lendemain du vendredi sanglant qui a frappé Paris, la bande-annonce de Made in France glace le sang.

Ce film de Nicolas Boukhrief devait sortir en salles mercredi 18 novembre. Son scénario : un journaliste indépendant infiltre les mosquées clandestines de la banlieue parisienne et se rapproche d’un groupe de jeunes djihadistes qui s’apprêtent à semer le chaos au cœur de la capitale. Le distributeur du film, Pretty Pictures, a annoncé samedi que sa sortie était repoussée et sa promotion annulée.

L’affiche de Made in France, elle aussi, a de quoi frapper les esprits. On y voit une tour Eiffel en forme de Kalachnikov géante, l’arme avec laquelle plusieurs assaillants ont tué plus de 120 personnes à Paris vendredi. L’affiche était placardée dans plusieurs espaces publicitaires de la RATP, gérés par la régie Metrobus. « Le producteur a demandé à ce qu’elle soit retirée, et nous avions décidé de la retirer de toute façon », indique un porte-parole de la RATP à Marianne. Un retrait qui a commencé dès la journée de samedi.

Made in France est un film d’autant plus prémonitoire qu’il a été tourné avant les attentats de janvier dernier. Dans la bande-annonce, l’un des personnages a cette phrase : « On est en guerre. Et dans toute guerre, il y a des victimes civiles. » Aucune nouvelle date de sortie n’a pour l’instant été communiquée.

(ndlr: La bande-annonce du films a été supprimée sur "youtube"!!!!!)

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Cinéma, Film | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : terrorisme, cinéma, film, censure, état policier, attentats de paris, paris, france |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 28 octobre 2015

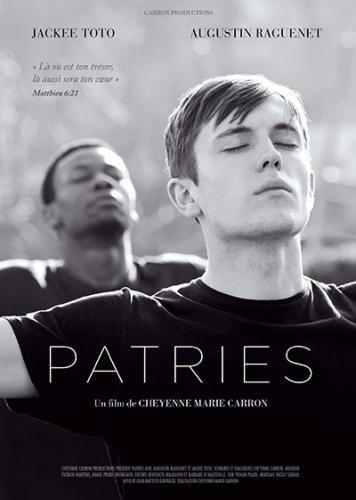

Patries. Un film choc de Cheyenne Carron sur le racisme anti-blanc et la remigration

Patries. Un film choc de Cheyenne Carron sur le racisme anti-blanc et la remigration

Le 21 octobre prochain sortira le nouveau film de la cinéaste indépendante Cheyenne Marie Carron , intitulé « Patries ». Un film particulièrement attendu car controversé avant même sa sortie, un film que nous avons pu visionner en exclusivité et en avant-première.

Cinéaste engagée, Cheyenne Marie Carron fait des films depuis 2001 sans bénéficier de la promotion et de l’aide dont bénéficient beaucoup de films qui ne font pourtant pas honneur au cinéma français. Sorti en 2014, son film L’Apôtre avait même suscité de violentes critiques et menaces parce qu’il évoquait l’histoire d’un jeune musulman désireux de se convertir au catholicisme. On se souvient même qu’une salle, à Nantes, avait déprogrammé le film après les attentats de janvier, de peur de représailles de la part d’islamistes.

N’ayant pas vu L’Apôtre, mon regard a donc pu se porter en toute objectivité sur le film Patries, film présenté comme traitant du racisme anti-blanc, dont j’avais vu la bande annonce au mois de mars dernier et lu le synopsis : « Sébastien et ses parents viennent d’emménager en banlieue parisienne. À son arrivée, il essaie de se faire accepter par un groupe de jeunes issus de l’immigration africaine. Malgré le rejet qu’il subit, une amitié complexe se noue avec Pierre, un jeune Camerounais en quête d’identité »

Quelle agréable surprise. Ou plutôt, quelle violente surprise. Car Patries est un film long-métrage coup de poing, une gifle en pleine figure, réalisé avec un budget équivalent à celui d’un clip publicitaire de 3 minutes effectués par des professionnels de la communication.

Un film intégralement tourné en noir et blanc et qui se divise en deux parties ; on suit d’abord principalement Sébastien (et le jeune acteur Augustin Raguenet) , jeune de la France périphérique obligé de suivre ses parents (dont son père aveugle) en banlieue parisienne, sa mère ayant trouvé un emploi à Paris. Très vite, il fait la connaissance de Pierre, un Camerounais qui le prends sous son aile et tente d’intégrer Sébastien à « sa bande », sans succès. Car Sébastien – éduqué par des parents ayant porté le « vivre ensemble » au statut de quasi-religion – va vite se rendre compte qu’il n’est pas le bienvenue dans cette banlieue, lui, le blanc, le babtou, la face de craie. La réalité des métropoles françaises et notamment de ses banlieues lui explose alors en plein visage sans que ses parents n’y comprennent rien et il deviendra rapidement une sorte de bouc émissaire pour deux « racailles » africaines ayant dès la première rencontre refusé de lui serrer la main en raison de sa couleur de peau. Seule solution pour lui ? Fuir, retourner dans la France périphérique, ou bien faire face, physiquement, et « s’intégrer » dans son propre pays.

La deuxième partie est centrée sur le personnage de Pierre, incarné par le brillant Jacky Toto, jeune Camerounais qui prend Sébastien sous son aile mais qui, suite à un mensonge non avoué de sa part, rompra de fait leur amitié et leur confiance naissante. Pierre – qui ne trouve pas de travail malgré sa volonté manifeste de réussir – est victime de DRH sans scrupules et d’une administration française qui ne pense qu’à l’aider, à l’assister, là où il voudrait réussir par lui même. Dans le même temps, il est en pleine crise identitaire, lui le Camerounais arrivé à 5 ans en France, jamais retourné au pays, mais n’ayant jamais su creuser sa place dans un pays qui n’est pas le sien. Doit-il partir et monter une entreprise au Cameroun, afin de réussir sa vie et d’aider son peuple , sur la terre de ses ancêtres ? Doit-il rester aux côtés de cette mère qui a tout sacrifié pour lui permettre une vie meilleure en France, et aux côtés de sa soeur, qui par le jeu d’une union mixte avec un bobo parisien français de souche, se sent beaucoup plus intégrée que lui ?

Le résultat est un film abouti, dont la scène finale ne pourra surprendre que ceux qui, habitant la France périphérique, ne connaissent pas ou n’ont pas connu la vie en banlieue, la vie d’un jeune blanc devenu étranger dans son propre pays. Durant ce film, qui, non sans un clin d’oeil appuyé à La Haine de Kassovitz , provoque un retour très violent au réel pour le spectateur, on se dit que du côté des enfants d’immigrés comme du côté des jeunes Français de souche, la cohabitation pacifique sera tout simplement impossible dans le futur, si ce n’est à la marge. Seuls les nantis ou les « vieux » comme dirait Julien Langella, et non pas les « anciens » , refusent de voir cette réalité, de l’admettre, alors même qu’elle est aujourd’hui communément admise par toute la jeunesse, quelle que soit sa couleur de peau ou son identité.

Patries est un film dur, violent psychologiquement, porté par une superbe bande-son particulièrement adaptée qui dévoile tantôt la foi chrétienne profonde de la réalisatrice, tantôt le ressenti de la rue, avec quelques morceaux de rap bien trouvés. C’est un film qui lève le voile sur une réalité jamais évoquée jusqu’ici par le cinéma français, trop souvent englué ces dernières années dans le politiquement correct et la médiocrité. Un film qui mériterait lui aussi d’être projeté dans toutes les salles obscures de France et d’être montré à la jeunesse de France, dans les collèges et les lycées. Car la réalité de la France des villes d’aujourd’hui, c’est plus Patries que L’Esquive, film médiocre sur des « jeunes de banlieue » qui avait, politiquement correct oblige, remporté 4 Césars alors même que la critique spectateurs ne lui accorde aujourd’hui que 2,6 sur 5 (2 962 notes) sur Allo Ciné.

Cheyenne Marie Carron est une cinéaste courageuse, au caractère bien trempé. C’est pourquoi elle a réussi avec brio ce film qui, au delà de ce qu’il montre, est techniquement réussi, surtout quand on connait le faible budget alloué. C’est pourquoi aussi, une certaine presse pourrait lui tomber rapidement dessus, ne pouvant admettre qu’une réalité certaine soit portée sur les écrans. Patries est en cette année 2015 au cinéma Français ce que « Catch Me Daddy » fut au cinéma anglais en 2014. Une révélation, une claque, à voir absolument à partir du mois d’octobre.

Plus d’informations sur le film ici

INTERVIEW

PATRIES

E.C : Le sujet du racisme anti-blanc, est assez tabou, avez-vous, vous-même subi du racisme ?

Cheyenne Carron : Je suis ni blanche, ni noire, mais marron clair de peau. Je n’ai jamais souffert de racisme de la part de personnes blanches ou noires. Depuis mon adolescence j’ai eu l’occasion de fréquenter des garçons et des filles issues de tous milieux et de toutes origines ethniques. J’ai observé les manifestations du racisme sous toutes ses formes. Aujourd’hui, j’ai pris assez de distance avec ce sujet pour pouvoir m’y intéresser. J’ai constaté que beaucoup de magnifiques films ont été fait dénonçant le racisme contre les noirs, je pense à « Imitation of Life », « 12 years a slave », ou « Dear white people », mais je n’ai jamais vu de films sur le racisme anti-blanc. Alors j’ai eu envie de corriger cela. Mais, avant de parler de racisme, Patries est surtout un film qui parle de différentes quêtes liées à l’identité.

E.C : N’avez-vous pas peur d’être taxée de racisme ?

C.C : Les valeurs dans lesquelles j’ai été élevée me mettent à l’abri de ce type de sentiment. J’ai des frères et sœurs blancs et un frère noir de peau. (Je viens d’une famille qui a adopté des enfants). Je ne suis pas raciste, et je pense donc qu’il est grand temps de parler des sujets qui fâchent ! Pour moi il ne s’agit pas de désigner des coupables et des victimes, mais il faut montrer le racisme mais aussi ceux qui l’exploitent en faisant mine de le condamner.

E.C : N’est-ce pas dangereux de traiter de ce sujet dans cette période compliqué ?

C.C : Il y a danger de se faire récupérer par des partis politiques extrêmes. Mais je pense qu’il y a aussi danger à ne pas s’emparer de ces sujets et de laisser à des gens sans humanité, et de les laisser pourrir dans la société… Et puis, je crois qu’un artiste doit s’emparer des problèmes de son temps.

E.C : Pour écrire ce scénario, vous êtes vous inspirée d’un livre, ou de faits divers ?

C.C : Je me suis inspirée du témoignage de plusieurs personnes. Elles m’ont raconté la manière dont elles tentaient de s’intégrer, mais aussi la manière dont elles vivaient une forme de rejet lié à leur couleur de peau, blanche ou noire.

E.C : Dans Patries vous nous montrez une famille, celle de Pierre, qui semble très attachée à son pays d’origine : le Cameroun.

C.C : Les sœurs de Pierre et sa mère, elles, sont très enracinées dans la culture Française, elles se sentent pleinement françaises. Pierre, lui, a un vrai désir qui grandit tout au long du film : celui de redécouvrir le pays d’où il vient. J’ai eu envie de parler d’un homme qui ne se sent pas heureux d’être en France, parce que sa culture d’origine lui manque. Je trouvais intéressant de montrer un immigré qui a soif de son identité perdue. Ça nous change du discourt habituel.. La France n’est pas son eldorado, il cherche autre chose. Pierre est aussi, d’une certaine façon, un héros. Il rêve de bâtir, et il croit en son destin. Mais pour lui, au fond de son cœur, son destin n’est pas en France. Son destin c’est le pays de ses ancêtres, alors que sa sœur ne jure que par la France.

E.C : Les deux mères de famille ont en point commun leur foi, c’est une thématique qui revient souvent dans vos films : la religion.

C.C : J’ai voulu faire le portrait de deux mères catholiques, à l’image de la mienne que j’aime. En tant qu’enfant abandonnée, j’aurais pu être adoptée par une maman noire, mais ce fut une maman blanche.

E.C : La notion de patrie incarne des réalités diverses selon le point de vue de chacun ; pour vous, quelle valeur a-t-elle ?

C.C : Moi qui ai été Pupille de l’État Français jusqu’à mes 19 ans, la patrie française ça a un sens. En tant qu’enfant abandonnée, j’ai bénéficié de la protection de l’État français et ça, ça n’a pas de prix. Mais il ne faut pas traiter les immigrés comme des enfants abandonnés ! Eux ont une terre quelque part, où ils sont nés, et où ils ont parfois une famille et des souvenirs. Un jour cette terre peut leur manquer, c’est le cas de Pierre.

E.C : Et où en êtes-vous avec le CNC ? J’ai cru comprendre que vos précédents films n’ont pas été subventionnés.

C.C : En 2014 le CNC m’a refusé deux scénarios (Hadès et Ma vie pour tes yeux lentement s’empoisonne), alors je ne présenterai plus mes scénarios à l’avenir. Je n’ai pas présenté Patries. J’ai beau faire ma maligne, à chaque refus ça me mine le moral et j’ai le sentiment que mon travail ne trouvera jamais grâce aux yeux du CNC. J’ai financé Patries avec l’argent que j’ai gagné sur les DVD de L’Apôtre.

E.C : Quels sont vos prochains projets ?

C.C : Je vais continuer à chercher le financement de « Hadès » et « Ma vie pour tes yeux lentement s’empoisonne », j’essaie d’élargir mon champ d’action à l’étranger. Si je n’y parviens pas, je vais devrais arrêter le cinéma. Je lui aurait donné tout ce que j’ai pu et Lui m’aura apporté beaucoup de joie et de réconfort.

Entretien avec Cheyenne-Marie Carron, réalisatrice

Cheyenne-Marie Carron est un OVNI. On ne croise pas un petit bout de femme comme elle tout les matins devant la haie de son champ.

Elle a été adoptée toute petite par une famille qui compte deux autres enfants adoptés ainsi que deux enfants “bio”. Elle est la réalisatrice d’une petite dizaine de films et commence à faire parler d’elle et notamment dans les médias rattachés à ce qu’on appelle la réacosphère. Un caractère bien trempé et une personnalité solaire: elle fait son petit bonhomme de chemin et à l’occasion de la sortie prochaine de son nouveau film, Patries, Cheyene-Marie Carron nous permet de nous intéresser à elle en nous accordant un entretien.

-Bonjour Madame, qui êtes-vous ? Pouvez-vous vous présenter succinctement aux lecteurs de Belle-et-Rebelle ?

J’ai 38 ans. Je suis une réalisatrice, scénariste et productrice, catholique.

-Quelle est la motivation qui pousse une jeune femme comme vous à réaliser un film aussi polémique que Patries, qui porte sur le racisme anti-blanc, ce thème tellement controversé ?

Ce qui me pousse n’est pas la polémique, mais l’injustice. Beaucoup de très beaux films existent sur le racisme contre les noirs, mais aucun sur le racisme contre les blancs. J’ai eu envie de corriger cela.

-D’après vous, pour quelles raisons le racisme anti-blanc est-il l’un des tabous de la France moderne?

Peut-être la peur… La peur de se rendre compte qu’on ne déracine pas impunément les gens sans que cela n’entraîne de conséquences.

Comment se manifeste selon vous le racisme anti-blanc ? -

Je pense qu’il prend sa source d’abord dans un mal-être. Celui de se sentir étranger à la culture française, avec peut-être un sentiment de honte et rage d’avoir abandonné son pays d’origine. Puis vient la conséquence, c’est à dire l’agression verbale ou physique de l’homme blanc, du Français.

Dans cette situation tout le monde souffre, d’abord la victime, le Français blanc de peau, mais aussi celui qui agresse.

-Quels obstacles avez-vous rencontrés dans la réalisation de votre film?

Aucun, car je n’ai rien demandé !

Le CNC m’a été refusé sur tous les films, et j’ai décidé de ne plus rien demander à cet organisme, ni aux régions. Je fais mes films sans argent, et je galère pas mal… mais je m’accroche.

-Cheyenne-Marie, soyez honnête, vous aimez vous compliquer la vie: femme, entrepreneure, politiquement incorrecte, catholique, artiste, j’en passe et des meilleures, vous cherchez les ennuis ?

Je ne cherche pas les ennuis, et si l’on m’en fait, je me défends, car j’ai le sentiment d’accomplir des choses justes.

-Est-ce que d’après vous, le harcèlement de rue des femmes ne relève pas aussi du racisme anti-blanc?

Ce harcèlement s’étend aussi à des femmes qui ne sont pas blanches. Il provient je crois d’un regard sur la femme occidentale qui prend sa source dans le mépris de notre culture.

Il faut que la femme occidentale par sa dignité et sa fierté en impose aux barbares.

-J’ai cru comprendre que vous n’êtes pas dans le circuit de distribution classique des films. Comment faites-vous pour faire voir vos films ? Avez-vous des idées de leur audience ?

Effectivement personne n’accepte de distribuer mes films, alors je prends mon courage à deux mains et frappe aux portes des cinémas. De manière étonnante, mes films voyagent aux quatre coins du monde grâce aux DVD et la VOD [Vidéo à la Demande; NDLR], et je reçois parfois des courriels d’encouragements venant de très loin. C’est ça aussi la magie d’un film, une fois terminé, il fait sa vie !

-Qu’est-ce qui vous révolte au quotidien?

Le manque de courage.

-Qu’est-ce qui vous fait garder l’espoir?

Ma foi en l’Eglise et en la France.

-Qu’est-ce qui vous émerveille ?

En ce moment, c’est le printemps qui m’émerveille…

-Qu’est-ce qui vous dégoûte?

L’orgueil.

-Les livres/images/œuvres/artistes/films qui ont fait de vous ce que vous êtes.

Ça n’est rien de tout ça.

Ce qui a fait ce que je suis devenue, c’est ma mère. Une sainte femme qui m’a recueillie lorsque j’avais 3 mois, et le prêtre de mon village qui m’a inspiré le film L’Apôtre. Cet homme a tendu la main à la famille du tueur de sa soeur.

Ces deux personnes sont les deux figures qui ont fait ce que je suis.

Ensuite, il y bien sûr des centaines de gens qui ont croisé ma route, et qui m’ont tendu la main !

-Votre idée du bonheur?

Avoir des enfants… ce que je n’ai pas pour le moment.

-Première chose que vous feriez si vous étiez présidente de la République.

Je restaurerai la Monarchie !

-Votre sucrerie préférée.

Les chocolats de Patrick Roger.

Son film, L’apôtre, est disponible en VOD ainsi qu’en DVD.

Patries sortira en septembre 2015.

00:05 Publié dans Cinéma, Film | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : cinéma, film, cheyenne-marie carron, france, racisme, anti-racisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 14 octobre 2015

Un autre cinéma est possible

Méridien Zéro #249: "Un autre cinéma est possible"

Cette semaine, Méridien Zéro a l'honneur et l'avantage de vous proposer un entretien avec la réalisatrice Cheyenne-Marie Carron, à quelques jours de la sortie de son film Patries (le 21 octobre). L'occasion pour nous d'éclairer l'oeuvre de cet auteur atypique et de revenir sur quelques aspects du cinéma français...

A la barre et à la technique Eugène Krampon et Wilsdorf.

00:05 Publié dans Cinéma, Entretiens, Film | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : cheyenne-marie caron, cinéma, méridien zéro, entretien, film |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 05 septembre 2015

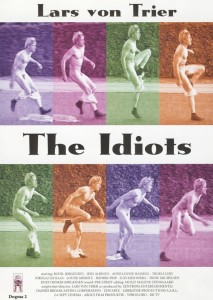

Lars von Trier’s The Idiots

Lars von Trier’s The Idiots

By Tonio Kröger

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

I. (Minor Spoilers)

The Idiots (Idioterne) is not an accessible film, and neither is it is easy to digest. The sexual content is so extreme that The Idiots is rated the same as any pornographic film in the United Kingdom, Spain, Australia, Norway, and several others. The depiction of mentally disabled individuals, both real and those merely acting as such, is alarming and controversial. During the screening at the Cannes Film Festival in 1998, film critic Mark Kermode was removed from the venue for exclaiming, ‘Il est merde!’ He was responding less to the actual quality of the film, and more to its remarkably provocative and unsettling subject matter.

Lars von Trier, of course, thrives on such reactions. His aim is to disturb and unnerve, to stir the viewer out of his seat and out of his comfort zone. This is done not simply for the ‘shock value’ in itself, as there is no legitimate artistic worth in managing to provoke or enrage the audience; instead this is done in order to communicate something through the shocking material. By knocking the viewer out of his ordinary perspective, where everything is comfortably perceived and organized according to a familiar worldview, Lars von Trier can assault him with a new perspective, a new challenge that might threaten his old way of viewing reality.

Lars von Trier, of course, thrives on such reactions. His aim is to disturb and unnerve, to stir the viewer out of his seat and out of his comfort zone. This is done not simply for the ‘shock value’ in itself, as there is no legitimate artistic worth in managing to provoke or enrage the audience; instead this is done in order to communicate something through the shocking material. By knocking the viewer out of his ordinary perspective, where everything is comfortably perceived and organized according to a familiar worldview, Lars von Trier can assault him with a new perspective, a new challenge that might threaten his old way of viewing reality.

This is truer of The Idiots than any other LvT film, and that includes the psychological horror of Antichrist and the raw sexual trauma of Nymphomaniac. This is due to the highly abrasive nature of the film’s narrative, which tells the story of a group of people who act like they are mentally retarded as a form of rebellion against what they understand to be a constrictive, conformist, and sterilizing society. Their antics, which they call ‘spazzing,’ include going into town to sell Christmas ornaments that they have made, going to the pool to create mischief with the other swimmers, and eating at restaurants only to spazz and leave without paying.

It is during the last antic that the group comes into contact with Karen, a seemingly ordinary person who becomes drawn and intimately attached to the spazz community over the next two weeks. Karen initially provides the neutral perspective of the group, the backdrop of normality to their witting insanity; she is very curious, though, and constantly questions the reasoning behind their activities, allowing the viewer to get a keener understanding of what they do. She firstly represents the ignorant audience who nevertheless desire to know more, but later, as we will see, she represents the fulfilment of the ‘spazz way of life.’

The group is led by a man named Stoffer, who is clearly the one who takes their mission the most seriously, ostensibly giving it an ideological basis and a higher cause than merely acting like idiots. Karen asks Stoffer why they do what they do, and Stoffer replies, ‘In the stone age all the idiots died. It doesn’t have to be like that nowadays. Being an idiot is a luxury, but it is also a step forward. Idiots are the people of the future. If one can find the one idiot that happens to be one’s own idiot . . .’ Stoffer finds in idiocy an outlet for what bourgeois society has repressed or camouflaged, namely a kind of personal creativity that does not accord with social normalcy. It is a new freedom, one which was obviously unavailable in a more brutal time, but which is presently imperative in an era that prizes comfort, material luxury, and ostracizes everything that is not conducive to ‘making one’s way in the world,’ i.e., becoming rich and popular. Stoffer asks meaningfully, ‘What’s the idea of a society that gets richer and richer when it doesn’t make anyone happier?’ Stoffer’s idea is instead to make one happier regardless of riches.

The means of achieving this are chiefly to ‘find the one idiot that happens to be one’s own idiot,’ a demonstrably individualistic and interiorized path that cannot help but hearken back to the Dionysian nature of the Breaking the Waves heroine, Bess. The idea is to determine the other side of oneself, the side that society has dispelled and rejected from its embrace. It is in this sense that we are reminded of C. G. Jung’s conception of the ‘shadow,’ or the secret personality that is imbued with our darker elements, with everything that has been evicted from and cannot fit into conscious life. Stoffer’s aim is essentially to reconcile modern man with his shadow self in a radical way; he aims to reintegrate man with his inner darkness to create something that is once again whole, independent of outer definitions and social parameters. When one character wakes him up, telling him that another spazzer is breaking things on the property, Stoffer responds, ‘Sheds are bourgeois crap. Smashing windows is obviously part of Axel’s inner idiot.’ The smashing of windows is an act that is socially reprehensible, but, since it allegedly exists as part of Axel’s ‘inner idiot,’ his ‘shadow self,’ it is perfectly acceptable in spazzer society.

This opposition between consciousness and the shadow is present not only in the individual sense, where the characters play out this drama in themselves, but in the collective sense as well. What this means is that the bourgeoisie, which is invariably treated as a great evil and as something to be rebelled against, represents the conscious side, and the spazzer society represents the shadow side; they are the ‘reservoir of darkness’ that has spilled out from respectable society, and has come to life after society has failed to suppress it. They even use society’s own tools against it, inverting the logic of social machinations to serve immoral ends. In one scene, for example, Stoffer has one of the spazzers pretend to have tripped over a loose cobblestone near a well-to-do homeowner’s property, then pesters the man to pay them off in order to avoid a lawsuit. When the wealthy man asks whether the spazzer didn’t simply trip on his own rather than a loose stone, Stoffer answers, ‘Are you saying they drag their feet? that they are clumsy?,’ which forces the man to retreat, unwilling to be responsible for anything that might be considered ‘politically incorrect.’ Stoffer considers this to be a victory over the ‘fascist’ system that he hates, contemptuously gazing into its soul and mocking it.

There are other scenes, too, that reveal other ‘victorious’ moments against other, more typical members of society. The house where they are staying, for example, is that of Stoffer’s uncle, who has entrusted Stoffer to sell it. When he visits the house, he remarks that he take better care of it, saying that, ‘These floors have been waxed every day for fifty years,’ which of course exemplifies the hated bourgeois attitude. Later on, coming into possession of caviar, Stoffer shows his group how to ‘eat it the way they eat caviar in Soelleroed [their town],’ stuffing it into his mouth as though he were a child eating chocolate. Allured by the antics of her new friends, Karen also learns to spazz, and though she meaningfully does not participate to the same extent as the others, she says that, ‘We’re so happy here. I’ve no right to be so happy.’

II (Major Spoilers)

The ‘paradise’ of Soelleroed is largely an illusion, however, as the final third of the film reveals. It is in these segments that the real darkness of the shadow comes out, which altogether reflects the failure of Stoffer’s mission to reconcile it with their conscious lives. This is as manifest in Stoffer himself as in any of the others. In one scene, for instance, a city official arrives at the house to offer them a government grant and a new location where they might stay, somewhere that is further away from normal society and which therefore makes it harder for them to intrude upon normal people. Stoffer of course reacts violently to this, ripping off his clothes and chasing the official all the way back to town naked, screaming ‘Fascist! fascist!’ the whole time. The others drag him back to the house, but they have to physically restrain him, strapping him to a bed overnight as he has reverted to a purely irrational state, succumbing to an episode that was formerly merely an act.

Another character, too, after the girl he fell in love with is stolen away from the house by her father, chases after him, running into his car, gesturing wildly and speaking nonsense. Affected so deeply by his feeling for her, he is no longer able to bridge the gap between his conscious self and the primitive he used to play at but has now become reality. This is not a successful integration between consciousness and the shadow; this is the conquest of the former by the latter, resulting in the personality regressing to something animalistic and instinctual. Stoffer’s experimentation in human happiness has failed, because there is no longer anything human in his subjects.

There are more obvious instances of this darkness, too. After the night which Stoffer spends in straps, they have a party, and at the end of the party he requests a gangbang. Most of his fellows willingly participate, but some do not; this leads Stoffer and another to chase one of the unwilling women down, essentially raping her in a violently disturbing scene of spazz sex. It is significant that Karen retreats from this scene altogether, abstaining from the evil that has infiltrated the rest of the ‘shadow group.’ It is even more significant that she is not raped, for she has maintained her own sense of self in contradistinction to the others; her personality is still intact while those of the others have been overwhelmed and utterly ransacked of their humanity.

Nearing the end of the film, Stoffer comes to doubt the sincerity of his fellow idiots, suspecting that this is all just some sort of game to them. He orders them to play ‘spin the bottle,’ with whomever the bottle points at having to demonstrate his commitment to the cause by spazzing in ‘real life’ places such as at work or at home with the wife and kids. The first fails completely, refusing to spazz in front of his family; he elects a normal life instead of the idiot life and the mistress he kept among them. The second opts to spazz in front of an art class he will be teaching, but he fails as well, causing Stoffer to storm out of the class, saying, ‘You love this middle class crap. These old dames use more make-up than the national theatre.’ The teacher, Henrik, says, ‘I had no pride in my inner idiot.’ The shadow self was just an illusion for them, something to play at in an insubstantial expression of inward identity.

Stoffer himself comes no closer to the reconciliation between the shadow and the ego. Instead of being the romantic and anarchic hero revolting against the oppressive bourgeois system that he likes to consider himself, he is infact a representation of it in its inverted sense; he is the ‘other side of the same coin,’ reflecting the absence of a genuine morality that extends to both the ‘middle class’ and the bohemian individualism. His ethos is fundamentally the same as that of his bourgeois uncle: ‘In reality, the acceptance of the shadow-side of human nature verges on the impossible. Consider for a moment what it means to grant the right of existence to what is unreasonable, senseless, and evil! Yet it is just this that the modern man insists upon. He wants to live with every side of himself — to know what he is. That is why he casts history aside. He wants to break with tradition so that he can experiment with his life and determine what value and meaning things have in themselves, apart from traditional presuppositions’ (C. G. Jung, ‘Psychotherapists or the Clergy’).

Stoffer is the epitome of the ‘modern man’ in that he wants to throw off all social inhibitions, not merely those of the 20th Century middle class, but the entire framework of human society. His revolt is the same as the student and hippy revolts of the sixties, revolts which were ultimately codified into the same bourgeois vassals that they originally reacted against. This is what makes Stoffer the superficial counterpart to the bourgeoisie; this is what makes him its useful idiot.

Karen is the only one who volunteers to spazz in her own life. Taking along her friend Suzanne for company, Karen returns to her home, somewhere she has not been for two weeks. We soon learn that her son had died, and that her son’s funeral was the day after she joined the group. Her husband comes home, and they sit down to eat – and Karen drools and dribbles at her food, which causes her family to stare, and her husband to hit her. Suzanne takes her hand, and they leave together, smiling naively, innocently.

Earlier in the film, Karen says to Stoffer, ‘I just want to be able to understand why I’m here,’ to which he replies, ‘Perhaps because there is a little idiot in there that wants to come out and have some company.’ While that is true in a certain, limited sense, it is truer to say that Karen’s ‘little idiot’ needed to come out to save her conscious self. Besieged by an impossible grief and a mother’s mourning, Karen’s ego longed for an escape route from the world’s immense difficulty. That she alone found it amongst all the idiots testifies both to the extent of her trauma and her extraordinary capability of dealing with it; she alone could make real sense of what the idiots were only playing at. Their reactions (aside from Stoffer, who was overcome by his own shadow) were conditioned by their belonging to the bourgeois order, something from which they recoiled in theory, but which they nevertheless could not do without; Karen’s reaction, on the other hand, was conditioned by a more profound disorder, which demanded an extreme process in order to be able to cope with it. Her struggle was far more real than that of the others, which is why she was the only one to find the solution to it.

The Idiots reveals both the positive and the negative scenarios that are the consequence of a Dionysiac revolt against the Apollonian dream-world. In order to ‘revolt successfully,’ to truly indulge in Dionysian fruit, the individual’s actions must be founded on something universally real that transcends particular circumstances; he must determine himself based on who he really is rather than merely a perception or a projection of who he is. This is where most of the idiots failed: ‘The shadow is a moral problem that challenges the whole ego-personality, for no one can become conscious of the shadow without considerable moral effort. To become conscious of it involves recognizing the dark aspects of the personality as present and real. This act is the essential condition for any kind of self-knowledge’ (C. G. Jung, Aion). The idiots never really became conscious of their shadow; they acted it out either as a meaningless game that allowed them an illusion of rebellion against their bourgeois lives, or, in the case of Stoffer, as a license to perform whatever irrational and pernicious acts that occurred to him, as long as they did not agree with the prevailing social order. They never addressed the shadow as a ‘moral problem,’ as something that directly influences the person; they addressed it as a ‘social problem,’ and thus remained chained to the illusions of Apollo’s dream-world.

Karen alone represents Dionysus as the purveyor of dynamic, uninhibited truth. She refused the moral violations of the other idiots, she refused their pretensions of abandoning society, and she refused their needless and unlawful interdictions with the rest of the town; in a word, Karen rejected rejection, and she did so because her rebellion was founded on an affirmation of self rather than on its negation. Unlike Stoffer, who loses control when he is confronted with that which he hates and fears most (the bourgeois city official), Karen maintains perfect control as she releases her inner idiot in front of her family, again exemplifying a personal command that eluded the others.

Speaking of her return home, where she demonstrates her restored personal strength, she says to the idiots, ‘We’ll see if I can show you if it has all been worthwhile.’ This follows a farewell in which Karen expresses an open, authentic love for many of the idiots, and repeats her avowal of happiness to have been amongst them. Karen’s family, cold, unfeeling, and uncomprehending of what it must be for a mother to lose her son, failed to ease her grief; it was only in her introspection, the confrontation with her ‘inner idiot’ as a lifeboat that carries her from the drowning ego, that actually saves the ego. By acknowledging her despair in this radical context, she could dilute and eventually sublimate it into something far more positive, to the extent that, all things considered, she does not even know why or how she can be so happy. In this sense, the freedom of Dionysus is attained not as a rejection of Apollo, but as a victorious affirmation of the reconciliation between the unconscious and the conscious; while the rest of the idiots founded their shadow-search on a rejection of Apollo, Karen had to be rejected by him instead. This is what led to her final freedom; this is what made it all worthwhile.

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2015/08/lars-von-triers-the-idiots/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: https://secure.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/TheIdiots.jpg

00:05 Publié dans Cinéma, Film | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : lars von trier, cinéma, film, danemark |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 26 avril 2015

Pasolini : le chant de l’abyme

Pasolini: le chant de l’abyme

« Scandaliser est un droit. Être scandalisé est un plaisir. Et le refus d’être scandalisé est une attitude moraliste. »

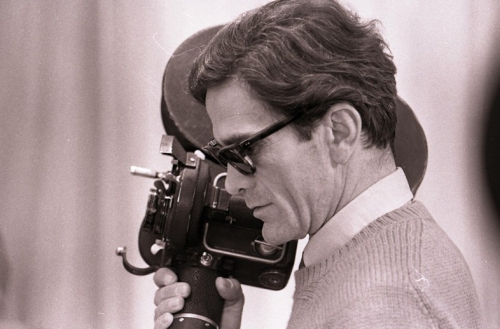

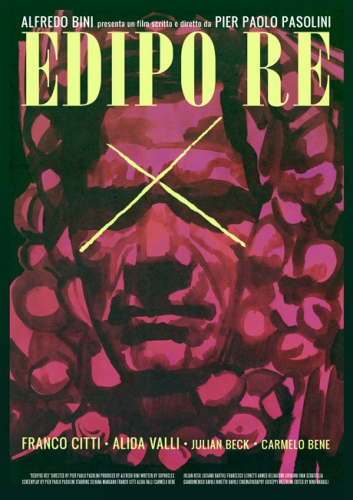

Devant le journaliste français qui l’interroge, Pier Paolo Pasolini ne mâche pas ses mots. Il ne l’a jamais fait. Il vient de terminer Salo ou les 120 journées de Sodome. Le lendemain, il sera mort. C’est ainsi que débute le beau film qu’Abel Ferrara a consacré à cet homme qui paya de sa vie son droit sacré au blasphème moderne.

Rassurons d’emblée ceux que les biopics convenus lassent ou exaspèrent : le film de Ferrara n’a pas l’ambition, ni la volonté, d’embrasser toute la vie du poète italien de façon linéaire. Son récit se concentre sur les derniers jours de sa vie, comme si ces ultimes instants recelaient en eux-mêmes toute sa puissance tragique et artistique.

Alternant les scènes de vie familiale avec les interviews politiques, Ferrara s’aventure également, à la manière des récits en cascade des Mille et une nuits, dans le champ de l’imaginaire en illustrant son roman inachevé Pétrole et les premières esquisses du film Porno-Teo-Kolossal racontant le voyage d’Epifanio et de son serviteur Nunzio à travers l’Italie à la recherche du Paradis, guidés par une comète divine. Enchâssant la fiction dans la réalité (et même la fiction dans la fiction), Ferrara trace une ligne de vie viscérale entre Pasolini et ses œuvres : « Pasolini n’était pas un esthète, mais un avant-gardiste non inscrit, affirme Hervé Joubert-Laurencin. Il n’a pas vécu sa vie comme un art mais l’art comme une vie, il n’était pas « décadentiste » mais « réaliste », il n’a pas « esthétisé la politique » mais « politisé l’art ». »

Et sa voix politique, frontale mais toujours respectueuse, a eu un retentissement phénoménal dans les années 1960/1970 en Italie et en Europe, en se heurtant au conservatisme politique et au puritanisme moral. La beauté de son cinéma politique résidait dans le regard cru qu’il portait sur les choses, notamment les plus triviales. Devant sa caméra elles ne se transformaient pas en verbiage théorique. Les choses restaient des choses, d’un réel trop éclatant, trop beau, trop vrai : « Je n’ai pas honte de mon « sentiment du beau ». Un intellectuel ne saurait être qu’extrêmement en avance ou extrêmement en retard (ou même les deux choses à la fois, ce qui est mon cas). C’est donc lui qu’il faut écouter : car la réalité dans son actualité, dans son devenir immédiat, c’est-à-dire dans son présent, ne possède que le langage des choses et ne peut être que vécue. » (Lettres luthériennes)

Vent debout face à la houle

Pasolini était un homme du refus. Mais pas circonstancié et tiède : « Pour être efficace, le refus ne peut être qu’énorme et non mesquin, total et non partiel, absurde et non rationnel. » (Nous sommes tous en danger) C’est tout ou rien. Pasolini était CONTRE. Contre la droite cléricale-fasciste et démocrate-chrétienne mais aussi contre les illusions de son propre camp, celui du gauchisme (cette « maladie verbale du marxisme ») et de ses petit-bourgeois d’enfants.

Pasolini était un homme du refus. Mais pas circonstancié et tiède : « Pour être efficace, le refus ne peut être qu’énorme et non mesquin, total et non partiel, absurde et non rationnel. » (Nous sommes tous en danger) C’est tout ou rien. Pasolini était CONTRE. Contre la droite cléricale-fasciste et démocrate-chrétienne mais aussi contre les illusions de son propre camp, celui du gauchisme (cette « maladie verbale du marxisme ») et de ses petit-bourgeois d’enfants.

Il était contre les belles promesses du Progrès qui font s’agenouiller les dévots de la modernité triomphante, ces intellos bourgeois marchant fièrement dans un « sens de l’Histoire » qu’ils supposent inéluctable et forcément bénéfique. « La plupart des intellectuels laïcs et démocratiques italiens se donnent de grands airs, parce qu’ils se sentent virilement « dans » l’histoire. Ils acceptent, dans un esprit réaliste, les transformations qu’elle opère sur les réalités et les hommes, car ils croient fermement que cette « acceptation réaliste » découle de l’usage de la raison. […] Je ne crois pas en cette histoire et en ce progrès. Il n’est pas vrai que, de toute façon, l’on avance. Bien souvent l’individu, tout comme les sociétés, régresse ou se détériore. Dans ce cas, la transformation ne doit pas être acceptée : son « acceptation réaliste » n’est en réalité qu’une manœuvre coupable pour tranquilliser sa conscience et continuer son chemin. C’est donc tout le contraire d’un raisonnement, bien que souvent, linguistiquement, cela en ait l’air. […] Il faut avoir la force de la critique totale, du refus, de la dénonciation désespérée et inutile. » (Lettres luthériennes)

« Les saints, les ermites, mais aussi les intellectuels, les quelques personnes qui ont fait l’histoire sont celles qui ont dit « non« , et pas les courtisans ou les assistants des cardinaux. »

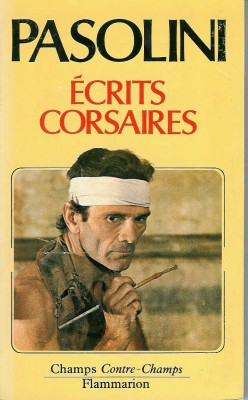

C’est aussi son rejet de la nouvelle langue technique qui aplatit tout sur son passage, écrasant les particularismes culturels et linguistiques, réduisant en poussière le discours humaniste et faisant du slogan le nouveau port-étendard d’un monde mort sur lequel l’individu narcissique danse jusqu’à l’épuisement. Et la gauche, qui ne veut pas rester hors-jeu, s’engouffre dans cette brèche en prêtant allégeance à la civilisation technologique, croyant, de façon arrogante, qu’elle apportera Salut et Renouveau sans percevoir qu’elle détruit tout sentiment et toute fierté chez l’homme. Les regrets pointent : « L’individu moyen de l’époque de Leopardi pouvait encore intérioriser la nature et l’humanité dans la pureté idéale objectivement contenue en elles ; l’individu moyen d’aujourd’hui peut intérioriser une Fiat 600 ou un réfrigérateur, ou même un week-end à Ostie. » (Écrits corsaires)