Ex: http://elfrentenegro.blogspot.com/

I

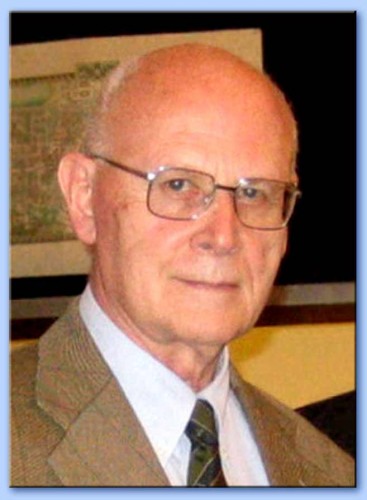

Ernst Jünger (1895-1998), autor de diarios claves sobre lo que se llamó la estética del horror, así como de un importante ensayo -El Trabajador- acerca de la cultura de la técnica moderna y sus repercusiones, está considerado, incluso por sus críticos más acerbos, como un gran estilista del idioma alemán, al que algunos incluso ponen a la altura de los grandes clásicos de la literatura germánica. Fue el último sobreviviente de una generación de intelectuales heredada de la obra de Oswald Spengler, Martin Heidegger, Carl Schmitt y Gottfried Benn. Apasionado polemista, nunca estuvo ajeno de la controversia política e ideológica de su patria; iconoclasta paradójico, enemigo del eufemismo, "anarquista reaccionario" en sus propias palabras, abominador de las dictaduras (fue expulsado del ejército alemán en 1944 después del fracaso del movimiento antihitlerista) y las democracias (dictaduras de la mayoría, como las llamó Karl Kraus, líder espiritual del círculo de Viena). En 1981, Jünger recibió el premio Goethe en Frankfurt, máximo galardón literario de la lengua germana. Sus obras, varias de ellas de carácter biográfico, giran sobre el eje de protagonistas en cuyas almas el autor intenta plasmar una cierta soledad y desencantamiento frente al mundo contemporáneo; al tema central, intercala disquisiciones acerca del origen y destino del hombre, filosofía de la historia, naturaleza del Estado y la sociedad. Por sobre esto, sus obras constituyen un llamado de denuncia y advertencia ante el avance incontenible y abrasador del nihilismo como movimiento mundial, a la vez que se convierten en guías para las almas rebeldes ante este proceso avasallador.

Ernst Jünger (1895-1998), autor de diarios claves sobre lo que se llamó la estética del horror, así como de un importante ensayo -El Trabajador- acerca de la cultura de la técnica moderna y sus repercusiones, está considerado, incluso por sus críticos más acerbos, como un gran estilista del idioma alemán, al que algunos incluso ponen a la altura de los grandes clásicos de la literatura germánica. Fue el último sobreviviente de una generación de intelectuales heredada de la obra de Oswald Spengler, Martin Heidegger, Carl Schmitt y Gottfried Benn. Apasionado polemista, nunca estuvo ajeno de la controversia política e ideológica de su patria; iconoclasta paradójico, enemigo del eufemismo, "anarquista reaccionario" en sus propias palabras, abominador de las dictaduras (fue expulsado del ejército alemán en 1944 después del fracaso del movimiento antihitlerista) y las democracias (dictaduras de la mayoría, como las llamó Karl Kraus, líder espiritual del círculo de Viena). En 1981, Jünger recibió el premio Goethe en Frankfurt, máximo galardón literario de la lengua germana. Sus obras, varias de ellas de carácter biográfico, giran sobre el eje de protagonistas en cuyas almas el autor intenta plasmar una cierta soledad y desencantamiento frente al mundo contemporáneo; al tema central, intercala disquisiciones acerca del origen y destino del hombre, filosofía de la historia, naturaleza del Estado y la sociedad. Por sobre esto, sus obras constituyen un llamado de denuncia y advertencia ante el avance incontenible y abrasador del nihilismo como movimiento mundial, a la vez que se convierten en guías para las almas rebeldes ante este proceso avasallador.

II

Pero, ¿qué es el nihilismo? Jünger, en un intercambio epistolar con Martin Heidegger, expuso sus conceptos sobre el nihilismo en el ensayo Sobre la línea (1949). Basándose en La voluntad de poder de F. Nietzsche, lo define, en primer término, como una fase de un proceso espiritual que lo abarca y al que nada ni nadie pueden sustraerse. En sí mismo, es un proceso determinado por "la devaluación de los valores supremos", en que el contacto con lo Absoluto es imposible: "Dios ha muerto". Nietzsche se caracteriza como el primer nihilista de Europa, pero que ya ha vivido en sí el nihilismo mismo hasta el fin. De esto Jünger recoge un Optimismo dentro del Pesimismo característico de este proceso, en el sentido de que Nietzsche anuncia un contramovimiento futuro que reemplazará a este nihilismo, aun cuando lo presuponga como necesario. También recoge síntomas del nihilismo en el Raskolnikov de Dostoievski, que "actúa en el aislamiento de la persona singular", dándole el nombre de ayuntamiento, proceso que puede resultar horrible en su epílogo, o ser la salvación del individuo luego de su purificación "en los infiernos", regresando a su comunidad con el reconocimiento de la culpa. Entre las dos concepciones, Jünger rescata un parentesco, el hecho de que progresan en tres fases análogas: de la duda al pesimismo, de ahí a acciones en el espacio sin dioses ni valores y después a nuevos cometidos. Esto permite concluir que tanto Nietzsche como Dostoievski ven una y la misma realidad, sí bien desde puntos muy alejados.

Jünger se encarga de limpiar y desmitificar el concepto de nihilismo, debido a todas las definiciones confusas y contradictorias que intelectuales posteriores a Nietzsche desarrollaron en sus trabajos, problema para él lógico debido a la "imposibilidad del espíritu de representar la Nada". Como problema principal, distingue el nihilismo de los ámbitos de lo caótico, lo enfermo y lo malo, fenómenos que aparecen con él y le han dado a la palabra un sentido polémico. El nihilismo depende del orden para seguir activo a gran escala, por lo que el desorden, el caos serían, como máximo, su peor consecuencia. A la vez, un nihilista activo goza de buena salud para responder a la altura del esfuerzo y voluntad que se exige a sí mismo y los demás. Para Nietzsche, el nihilismo es un estado normal y sólo patológico, por lo que comprende lo sano y lo enfermo a su particular modo. Y en cuanto a lo malo, el nihilista no es un criminal en el sentido tradicional, pues para ello tendría que existir todavía un orden válido.

El nihilismo, señala Jünger, se caracteriza por ser un estado de desvanecimiento, en que prima la reducción y el ser reducido, acciones propias del movimiento hacia el punto cero. Si se observa el lado más negativo de la reducción, aparece como característica tal vez más importante la remisión del número a la cifra o también del símbolo a las relaciones descarnadas; la confusión del valor por el precio y la vulgarización del tabú. También es característico del pensamiento nihilista la inclinación a referir el mundo con sus tendencias plurales y complicadas a un denominador; la volatización de las formas de veneración y el asombro como fuente de ciencia y un "vértigo ante el abismo cósmico" con el cual expresa ese miedo especial a la Nada. También es inherente al nihilismo la creciente inclinación a la especialización, que llega a niveles tan altos que "la persona singular sólo difunde una idea ramificada, sólo mueve un dedo en la cadena de montaje", y el aumento de circulación de un "número inabarcable de religiones sustitutorias", tanto en las ciencias, en las concepciones religiosas y hasta en los partidos políticos, producto de los ataques en las regiones ya vaciadas.

Según lo expresado en Sobre la línea, es la disputa con Leviatán -ente que representa las fuerzas y procesos de la época, en cuanto se impone como tirano exterior e interior-, es la más amplia y general en este mundo. ¿Cuáles son los dos miedos del hombre cuando el nihilismo culmina? "El espanto al vacío interior, obligando a manifestarse hacia fuera a cualquier precio, por medio del despliegue de poder, dominio espacial y velocidad acelerada. El otro opera de afuera hacia adentro como ataque del poderoso mundo a la vez demoníaco y automatizado. En ese juego doble consiste la invencibilidad del Leviatán en nuestra época. Es ilusorio; en eso reside su poder". La obra de Jünger trastoca el tema de la resistencia; se plantea la pregunta sobre cómo debe comportarse y sostenerse el hombre ante la aniquilación frente a la resaca nihilista.

"En la medida en que el nihilismo se hace normal, se hacen más temibles los símbolos del vacío que los del poder. Pero la libertad no habita en el vacío, mora en lo no ordenado y no separado, en aquellos ámbitos que se cuentan entre los organizables, pero no para la organización". Jünger llama a estos lugares "la tierra salvaje", lugar en el cual el hombre no sólo debe esperar luchar, sino también vencer. Son estos lugares a los cuales el Leviatán no tiene acceso, y lo ronda con rabia. Es de modo inmediato la muerte. Aquí dormita el máximo peligro: los hombres pierden el miedo. El segundo poder fundamental es Eros; "allí donde dos personas se aman, se sustraen al ámbito del Leviatán, crean un espacio no controlado por él". El Eros también vive en la amistad, que frente a las acciones tiránicas experimenta sus últimas pruebas. Los pensamientos y sentimientos quedan encerrados en lo más íntimo al armarse el individuo una fortificación que no permite escapar nada al exterior; "En tales situaciones la charla con el amigo de confianza no sólo puede consolar infinitamente sino también devolver y confirmar el mundo en sus libres y justas medidas". La necesidad entre sí de hombres testigos de que la libertad todavía no ha desaparecido harán crecer las fuerzas de la resistencia. Es por lo que el tirano busca disolver todo lo humano, tanto en lo general y público, para mantener lo extraordinario e incalculable, lejos.

Este proceso de devaluación de los valores supremos ha alcanzado, de algún modo, caracteres de "perfección" en la actualidad. Esta "perfección" del nihilismo hay que entenderla en la acepción de Heidegger, compartida por Jünger, como aquella situación en que este movimiento "ha apresado todas las consistencias y se encuentra presente en todas partes, cuando nada puede suponerse como excepción en la medida en que se ha convertido en el estado normal." El agente inmediato de este fenómeno radica en el desencuentro del hombre consigo mismo y con su potencia divina. La obra de Jünger, en este sentido, da cuenta del afán por radicar el fundamento del hombre.

III

Uno de los síntomas de nuestra época es el temor. Aquel temor que hace afirmar al autor que toda mirada no es más que un acto de agresión y que hace radicar la igualdad en la posibilidad que tienen los hombres de matarse los unos a los otros. A lo anterior, hay que agregar la inclinación a la violencia que desde el nacimiento todos traemos, según lo señalado en su novela "Eumeswil" (1977). . Por eso el mundo se torna en imperfecto y hostil. Su historia no es sino la de un cadáver acechado una y otra vez por enjambres de buitres. Esta visión lúgubre de la realidad, en la que se encuentra una reminiscencia schopenhaueriana, fue sin duda alimentada por la experiencia personal del autor, testigo del horror de dos guerras implacables que no hicieron más que coronar e instaurar en el mundo el culto a la destrucción, al fanatismo y la masificación del hombre. El avance de la técnica, a pesar de los beneficios que conlleva, a juicio de Jünger tiene la contrapartida de limitar la facultad de decisión de los hombres en la medida en que a favor de los alivios técnicos van renunciando a su capacidad de autodeterminación conduciendo, luego, a un automatismo generalizado que puede llevar a la aniquilación. La pregunta que surge entonces es cómo el hombre puede superarlo, a través de que medios puede salvarse. La respuesta de Jünger, en boca de uno de sus personajes principales, el anarca Venator: la salvación está en uno mismo. El anarca, que nada tiene que ver con el anarquista, expulsa de sí a la sociedad, ya que tanto de ésta como del Estado poco cabe esperar en la búsqueda de sí mismo. El no se apoya en nadie fuera de su propio ser; su propósito es convertirse en soberano de su propia persona, porque la libertad es, en el fondo, propiedad sobre uno mismo.

Aparecen en este momento dos afirmaciones que pueden aparecer como contradictorias: el hombre inclinado a la violencia desde su nacimiento, y el hombre que debe penetrar en un conocimiento interior con el fin de descubrir su forma divina. Jünger afirma que la riqueza del hombre es infinitamente mayor de lo que se piensa. ¿Cómo conciliar esto con el carácter perverso que le atribuye al mismo? Al responder esto, el escritor apela a una instancia superior a la que denomina Uno, Divinidad, lo Eterno, según lo que se colige sobre todo en su obra posterior a 1950. La relación entre el hombre y lo Absoluto, expuesta por el maestro alemán, se entiende del siguiente modo: el ser, forma o alma de cada uno de nosotros ha estado, desde siempre, es decir, antes de nacer, en el seno de la Divinidad, y, después de la muerte, volverá a estar con ella. Antes de nacer, es tal el grado de indeterminación de esa unidad en lo Uno que el hombre no puede tener conciencia de la misma. Sólo cuando el nacimiento se produce, el hombre se hace consciente de su anterior unidad y busca desesperadamente volver a ella, al sentirse un ser solitario. Es allí cuando debe dirigirse hacia sí mismo, penetrar en su alma que es la eterna manifestación de lo divino. En el conócete a ti mismo, el hombre puede acceder a la forma que le es propia, proceso que para Jünger es un "ver" que se dirige hacia el ser, la idea absoluta. Señala en El trabajador que la forma es fuente de dotación de sentido, y la representación de su presencia le otorga al hombre una nueva y especial voluntad de poder, cuyo propósito radica en el apoderamiento de sí mismo, en lo absoluto de su esencia, ya que el objeto del poder estriba en el ser-dueño... En consecuencia, en ese descubrimiento de ser atemporal e inalterable que le confiere sentido, el hombre puede hacerse propietario de éste y convertirse en un sujeto libre. En caso contrario, quien no posea un conocimiento de sí mismo es incapaz de tener dominio sobre su ser no pudiendo, por tanto, sembrar orden y paz a su alrededor. En conclusión, esta inclinación a la violencia que surge con el nacimiento del hombre, en otras palabras, con su separación de lo Uno en la identidad primordial y primigenia dando lugar a la negación de la Divinidad, puede ser dominada y contrarrestada en la medida que el hombre se convierta en dueño de sí mismo, para lo cual es fundamental el conocimiento de la forma que nos otorga sentido.

La sustancia histórica, señala Jünger, radica en el encuentro del hombre consigo mismo. Ese encuentro con el ser supratemporal que le dota de sentido lo simboliza con el bosque. En su obra El tratado del rebelde afirma: "La mayor vigencia del bosque es el encuentro con el propio yo, con la médula indestructible, con la esencia de que se nutre el fenómeno temporal e individual". Es, entonces, el lugar donde se produce la afirmación de la Divinidad, al adquirir el sujeto la conciencia misma como partícipe de la identidad con lo Eterno.

El Verbo, entendido como "la materia del espíritu", es el más sublime de los instrumentos de poder, y reposa entre las palabras y les da vida. Su lugar es el bosque. "Toda toma de posesión de una tierra, en lo concreto y en lo abstracto, toda construcción y toda ruta, todos los encuentros y tratados tienen por punto de partida revelaciones, deliberaciones, confirmaciones juradas en el Verbo y en el lenguaje", enuncia en El tratado del rebelde. El lenguaje es, en definitiva, un medio de dominación de la realidad, puesto que a través de él aprehendemos sus formas últimas, en la medida en que es expresión de la idea absoluta. En una época tan abrumadoramente nihilista como la contemporánea, el propio autor describe como el lenguaje va siendo lentamente desplazado por las cifras.

En la obra de Jünger, el hombre que no acepta el "espíritu del tiempo" y se "retira hacia sí mismo" en busca de su libertad, es un rebelde. A partir de un ensayo de 1951, Jünger había propuesto una figura de rebelde a las leyes de la sociedad instalada, el Waldgänger que, según una antigua tradición islandesa, se escapa a los bosques en busca de sí mismo y su libertad. Posteriormente, el autor desarrolla la figura del rebelde en la novela Eumeswil, publicada en 1977, definiendo la postura del anarca, tipo que encarnaría el distanciamiento frente a los peores aspectos del nihilismo actual; o como el único camino digno a seguir para los hombres de verdad libres.

IV

Como en Heliópolis, en Eumeswil, Jünger nos presenta un mundo aún por llegar: se vive allí el estado consecutivo a los Grandes Incendios -una guerra mundial, evidentemente- y a la constitución y posterior disolución del Estado Mundial. Un mundo simplificado, en que aparecen formas semejantes a las del pasado: los principados de los Khanes, las ciudades-estados. El autor marca el carácter postrero del ambiente que da a su novela, comparándola a la época helenística que sigue a Alejandro Magno, una ciudad como Alejandría, ciudad sin raíces ni tradición. De modo análogo, en la sociedad de Eumeswil las distinciones de rangos, de razas o clases han desaparecido; quedan sólo individuos, distinguidos entre ellos por los grados de participación en el poder. Se posee aún la técnica, pero como algo más bien heredado de los siglos creadores en este dominio. La técnica permite, por ejemplo -siendo esto otro rasgo alejandrino-, un gran acopio de datos sobre el pasado, pero este pasado ya no se comprende.

Se enfrentan en Eumeswil dos poderes: el militar y el popular, demagógico, de los tribunos. Del elemento militar ha salido el Cóndor, el típico tirano que restablece el orden y, con él, las posibilidades de la vida normal, cotidiana, de los habitantes. Pero se trata de un puro poder personal, informe, que ya no puede restaurar la forma política desvanecida. Por lo demás tampoco en Eumeswil se tiene la ilusión de la gran política; no se trata siquiera de una potencia, viviendo como vive bajo la discreta protección del Khan Amarillo. En suma, son las condiciones de la civilización spengleriana, las de toda época final en el decurso de las culturas. "Masas sin historia", "Estados de fellahs", como señala Jünger.

El protagonista y narrador de la novela es Martín Venator, "Manuelo" en el servicio nocturno de la alcazaba del Cóndor. Es un historiador de oficio: aplica al pasado sus cualidades de observador, y de allí las reflexiones sobre el tiempo presente. Su modelo es, sin duda, Tácito: senador bajo los Césares, celoso del margen de libertad que aún puede conservar, escéptico frente a los hombres y frente al régimen imperial.

Venator también es camarero, barman en la alcazaba: como en las cortes de otra época, el servicio personal y doméstico al señor resulta ennoblecido. El camarero suele ser asimismo un observador, y en este terreno se encuentra con el historiador.

El historiador se retira voluntariamente al pasado, donde se encuentra en realidad "en su casa", y en este modo se aparta de la política. La derrota, el exilio, han sido a veces la condición de desarrollo de una vocación historiográfica -Tucídides en la Antigüedad, por ejemplo-, pero en otras ocasiones el historiador ha tomado parte activa de las luchas de su tiempo. En la novela, tanto el padre como el hermano del protagonista también son historiadores, pero, a diferencia de éste, están ideológicamente "comprometidos": son buenos republicanos, liberales doctrinarios, cautos enemigos del Cóndor más ajenos al mundo de los hechos que éste representa. Ellos deploran que "Manuelo" haya descendido a tan humilde servicio al tirano. Servicio fielmente prestado, pero en ningún caso incondicional. Entre los enemigos del Cóndor están los anarquistas: conspiran, ejecutan atentados... nada que la policía del tirano no logre controlar. De ellos se diferencia claramente Venator: no es un anarquista, es un anarca.

V

La mejor definición para la posición del anarca pasa por su relación y distinción de las otras figuras, las otras individualidades que se alzan, cada una a su modo, frente al Estado y la sociedad: el anarquista, el partisano, el criminal, el solipsista; o también, del monarca absoluto, como Tiberio o Nerón. Pues en el hombre y en la historia hay un fondo irrenunciable de anarquía, que puede aflorar o no a la superficie, y en mayor o menor grado, según los casos. En la historia, es el elemento dinámico que evita el estancamiento, que disuelve las formas petrificadas. En el hombre, es esa libertad interior fundamental. De tal modo que el guerrero, que se da su propia ley, es anárquico, mientras que el soldado no. En aparente paradoja, el anarquista no es anárquico, aunque algo tiene, sin duda. Es un ser social que necesita de los demás; por lo menos de sus compañeros. Es un idealista que, al fin y al cabo, resulta determinado por el poder. "Se dirige contra la persona del monarca, pero asegura la sucesión".

El anarca, por su parte, es la "contrapartida positiva" del anarquista. En propias palabras de Jünger: "El anarquista, contrariamente al terrorista, es un hombre que en lo esencial tiene intenciones. Como los revolucionarios rusos de la época zarista, quiere dinamitar a los monarcas. Pero la mayoría de las veces el golpe se vuelve contra él en vez de servirlo, de modo que acaba a menudo bajo el hacha del verdugo o se suicida. Ocurre incluso, lo cual es claramente más desagradable, que el terrorista que ha salido con bien siga viviendo en sus recuerdos...El anarca no tiene tales intenciones, está mucho más afirmado en sí mismo. El estado de anarca es de hecho el estado natural que cada hombre lleva en sí. Encarna más bien el punto de vista de Stirner, el autor de El único y su propiedad ; es decir, que él es lo único. Stirner dice: "Nada prevalece sobre mí". El anarca es, de hecho, el hombre natural". No es antagonista del monarca, sino más bien su polo opuesto. Tiene conciencia de su radical igualdad con el monarca; puede matarlo, y puede también dejarlo con vida. No busca dominar a muchos, sino sólo dominarse a sí mismo. A diferencia del solipsista, cuenta con la realidad exterior. No busca cambiar la ley, como el anarquista o el partisano; no se mueve, como éstos en el terreno de las opciones políticas o sociales. Tampoco busca trasgredir la ley, como el criminal; se limita a no reconocerla. El anarca, pues, no es hostil al poder, ni a la autoridad, ni a la ley; entiende las normas como leyes naturales.

No adhiere el anarca a las ideas, sino a los hechos; es en esencia pragmático. Está convencido de la inutilidad de todo esfuerzo ("tal vez esta actitud tenga algo que ver con la sobresaturación de una época tardía"). Neutral frente al Estado y a la sociedad, tiene en sí mismo su propio centro. Los regímenes políticos le son indiferentes; ha visto las banderas, ya izadas, ya arriadas. Jünger afirma, además, que aquellas banderas son sólo diferentes en lo externo, porque sirven a unos mismos principios, los mismos que harán que " toda actitud que se aparte del sistema, sea maldita desde el punto de vista racional y ético, y luego proscrita por el derecho y la coacción." No obstante, el anarca puede cumplir bien el papel que le ha tocado en suerte. Venator no piensa desertar del servicio del Cóndor, sino, por el contrario, seguir lealmente hasta el final. Pero porque él quiere; él decidirá cuando llegue el momento. En definitiva, el anarca hace su propio juego y, junto a la máxima de Delfos, "conócete a ti mismo", elige esta otra: "hazte feliz a ti mismo".

La figura del anarca resplandece verdaderamente, como la del hombre libre frente al Estado burocrático y a la sociedad conformista de la actualidad. Incluso aparece en algunas ocasiones en forma más bien mezquina, a la manera del egoísmo de Stirner: "quien, en medio de los cambios políticos, permanece fiel a sus juramentos, es un imbécil, un mozo de cuerda apto para desempeñar trabajos que no son asunto suyo". "(El anarca) sólo retrocede ante el juramento, el sacrificio, la entrega última". "Sólo cabe una norma de conducta" -dice Attila, médico del Cóndor, anarca a su modo- "la del camaleón..."

VI

La cuestión es si el anarca se constituye en una figura ejemplar para cierto tipo de hombres que no se reconozcan en las producciones sociales últimas. Pues si el anarca es la "actitud natural" -"el niño que hace lo que quiere"-, entonces nos hallamos ante simples situaciones de hecho que no tienen ningún valor normativo ni ejemplar. Desde siempre los hombres han querido huir del dolor y buscar lo agradable; por otro lado, apartarse de una sociedad decadente y que llega a ser asfixiante es una cosa sana. Venator invoca a Epicuro como modelo; debería referirse más bien a Aristipo de Cirene, discípulo de Sócrates y fundador de la escuela hedonista, quien proponía una vida radicalmente apolítica, "ni gobernante ni esclavo", con la libertad y el placer como únicos criterios. Jünger reconoce, y muy de buena gana, que el tipo de anarca se encuentra, socialmente hablando, en el pequeño burgués, piedra de tope de más de una corriente de pensamiento: es ese artesano, ese tendero independiente y arisco frente al Estado. La figura del anarca es más familiar al mundo anglosajón, especialmente al norteamericano, con su sentido ferozmente individualista y antiestatal: del cowboy solitario o del outlaw al "objetor de conciencia". Están en la mejor línea del anarca y el rebelde contra la masificación burocrática. Se sabe, por supuesto, en qué condiciones sociales han florecido estos modelos.

Pero las sociedades "posmodernas" actuales se distinguen por el más vulgar hedonismo; su tipo no es el del "superhombre", sino el del "último hombre" nietzscheano, el que cree haber descubierto la felicidad. El tipo del "idealista" y del "militante" pertenecen a etapas ya superadas; hoy, es el individuo de las sociedades "despolitizadas", soft, que toma lo que puede y rehusa todo esfuerzo. ¿Cuál es la diferencia de este tipo de hombre con el anarca? La respuesta radica en que el segundo está libre de todas las ataduras sentimentales, ideológicas y moralistas que aún caracterizan al primero. En verdad, la figura de Venator está históricamente condicionada: aparece en una de esas épocas postreras en la cuales nada se puede ya esperar. Lo que hay que esclarecer es si efectivamente nuestra propia época es una de ellas. Pero lo dicho sobre el anarca tiene un alcance mucho más universal: en cualquier tiempo y lugar se puede ser anarca, pues "en todas partes reina el símbolo de la libertad".

La senda del anarca termina en la retirada. Venator ha estado organizando una "emboscadura" temporal -según lo que el mismo Jünger recomendaba en Der Waldgang (1951)-, para el caso de caída del Cóndor. Al final, seguirá a éste, con toda su comitiva, en una expedición de caza a las selvas misteriosas más allá de Eumeswil: una emboscadura radical, o la muerte, no se sabe el desenlace. Del mismo modo, en Heliópolis, el comandante Lucius de Geer y sus compañeros se retiran en un cohete, con destino desconocido. Pero eso sí, después de haber luchado sus batallas, al igual que los defensores de la Marina en Sobre los Acantilados de Mármol no buscan refugio sino después de dura lucha con las fuerzas del Gran Guardabosques. Pero ¿de qué se trata esta "emboscadura"?

El anarca hace lo que Julius Evola, el gran pensador italiano, recomienda en su libro Cabalgar el tigre: "La regla a seguir puede consistir, entonces, en dejar libre curso a las fuerzas y procesos de la época, permaneciendo firmes y dispuestos a intervenir cuando el tigre, que no puede abalanzarse sobre quien lo cabalga, esté fatigado de correr". Lo que Evola llama "tigre", Jünger lo denomina "Leviatán" o "Titanic".

El anarca se retira hacia sí mismo porque debe esperar su hora; el mundo debe ser cumplido totalmente, la desacralización, el nihilismo y la entropía deberán ser totales: lo que Vintila Horia llama "universalización del desastre". Jünger enfatiza que emboscarse no significa abandonar el "Titanic", puesto que eso sería tirarse al mar y perecer en medio de la navegación. Además: "Bosque hay en todas partes. Hay bosque en los despoblados y hay bosque en las ciudades; en éstas, el emboscado vive escondido o lleva puesta la máscara de una profesión. Hay bosque en el desierto y hay bosque en las espesuras. Hay bosque en la patria lo mismo que lo hay en cualquier otro sitio donde resulte posible oponer resistencia... Bosque es el nombre que hemos dado al lugar de la libertad... La nave significa el ser temporal; el bosque, el ser sobretemporal...". En la figura del rebelde, por tanto, es posible distinguir dos denominaciones: emboscado y anarca. El primero presentaría las coordenadas espirituales, mientras el segundo da luces sobre su plasmación en el "aquí y ahora". Jünger lo define más claramente: "Llamamos emboscado a quien, privado de patria por el gran proceso y transformado por él en un individuo aislado, está decidido a ofrecer resistencia y se propone llevar adelante la lucha, una lucha que acaso carezca de perspectiva. Un emboscado es, pues, quien posee una relación originaria con la libertad... El emboscado no permite que ningún poder, por muy superior que sea, le prescriba la ley, ni por la propaganda, ni por la violencia".

VII

El nihilismo y la rebeldía... La figura del anarca es la de quien ha sobrevivido al "fin de la historia" ("carencia de proyecto: malestar o sueño"). El último hombre no puede expulsar al anarca que convive junto a él. Su poder radica en su impecable soledad y en el desinterés de su acción. Su sí y su no son fatales para el mundo que habita. El anarca se presenta como la victoria y superación del nihilismo. Las utopías le son ajenas, pero no el profundo significado que se esconde tras ellas. "El anarca no se guía por las ideas, sino por los hechos. Lucha en solitario, como hombre libre, ajeno a la idea de sacrificarse en pro de un régimen que será sustituído por otro igualmente incapaz, o en pro de un poder que domine a otro poder".

El anarca ha perdido el miedo al Leviatán, en el encuentro con la médula indestructible que le dota de sentido para luego proyectarse y reconocerse en el otro, en la amada, en el hermano, en el que sufre y en el desamparado, puesto que Eros es su aliado y sabe que no lo abandonará...

La actitud del anarca puede ser interpretada desde dos perspectivas, una activa y otra pasiva. Esta última verá en la emboscadura, y en el anarca que la realiza, la posibilidad de huir del presente y aislarse en aquella patria que todos llevamos en nuestro interior; al decir de Evola, la que nadie puede ocupar ni destruir. Pero no debe confundirse la actitud del anarca como una simple huida: "Ya hemos apuntado que ese propósito no puede limitarse a la conquista de puros reinos interiores". Mas bien se trata de otro tipo de acción, de un combate distinto, "donde la actuación pasaría entonces a manos de minorías selectas que prefieren el peligro a la esclavitud". Minorías que entiendan que emboscarse es dar lucha por lo esencial, sin tiempo y acaso sin perspectivas. Minorías que, como el propio Jünger lo expresa, sean capaces de llevar adelante la plasmación de una "nueva orden", que no temerá y, por el contrario, gustará de pertenecer al bando de los proscritos, pues se funda en la camaradería y la experiencia; orden que pueda llevar a buen término la travesía más allá del "meridiano cero", y se prepare a dar una lucha en el "aquí y ahora"...

"En el seno del gris rebaño se esconden lobos, es decir, personas que continúan sabiendo lo que es la libertad. Y esos lobos no son sólo fuertes en sí mismos: también existe el peligro de que contagien sus atributos a la masa, cuando amanezca un mal día, de modo que el rebaño se convierta en horda. Tal es la pesadilla que no deja dormir tranquilos a los que tienen el poder".

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Ernst Jünger (1895-1998), autor de diarios claves sobre lo que se llamó la estética del horror, así como de un importante ensayo -El Trabajador- acerca de la cultura de la técnica moderna y sus repercusiones, está considerado, incluso por sus críticos más acerbos, como un gran estilista del idioma alemán, al que algunos incluso ponen a la altura de los grandes clásicos de la literatura germánica. Fue el último sobreviviente de una generación de intelectuales heredada de la obra de Oswald Spengler, Martin Heidegger, Carl Schmitt y Gottfried Benn. Apasionado polemista, nunca estuvo ajeno de la controversia política e ideológica de su patria; iconoclasta paradójico, enemigo del eufemismo, "anarquista reaccionario" en sus propias palabras, abominador de las dictaduras (fue expulsado del ejército alemán en 1944 después del fracaso del movimiento antihitlerista) y las democracias (dictaduras de la mayoría, como las llamó Karl Kraus, líder espiritual del círculo de Viena). En 1981, Jünger recibió el premio Goethe en Frankfurt, máximo galardón literario de la lengua germana. Sus obras, varias de ellas de carácter biográfico, giran sobre el eje de protagonistas en cuyas almas el autor intenta plasmar una cierta soledad y desencantamiento frente al mundo contemporáneo; al tema central, intercala disquisiciones acerca del origen y destino del hombre, filosofía de la historia, naturaleza del Estado y la sociedad. Por sobre esto, sus obras constituyen un llamado de denuncia y advertencia ante el avance incontenible y abrasador del nihilismo como movimiento mundial, a la vez que se convierten en guías para las almas rebeldes ante este proceso avasallador.

Ernst Jünger (1895-1998), autor de diarios claves sobre lo que se llamó la estética del horror, así como de un importante ensayo -El Trabajador- acerca de la cultura de la técnica moderna y sus repercusiones, está considerado, incluso por sus críticos más acerbos, como un gran estilista del idioma alemán, al que algunos incluso ponen a la altura de los grandes clásicos de la literatura germánica. Fue el último sobreviviente de una generación de intelectuales heredada de la obra de Oswald Spengler, Martin Heidegger, Carl Schmitt y Gottfried Benn. Apasionado polemista, nunca estuvo ajeno de la controversia política e ideológica de su patria; iconoclasta paradójico, enemigo del eufemismo, "anarquista reaccionario" en sus propias palabras, abominador de las dictaduras (fue expulsado del ejército alemán en 1944 después del fracaso del movimiento antihitlerista) y las democracias (dictaduras de la mayoría, como las llamó Karl Kraus, líder espiritual del círculo de Viena). En 1981, Jünger recibió el premio Goethe en Frankfurt, máximo galardón literario de la lengua germana. Sus obras, varias de ellas de carácter biográfico, giran sobre el eje de protagonistas en cuyas almas el autor intenta plasmar una cierta soledad y desencantamiento frente al mundo contemporáneo; al tema central, intercala disquisiciones acerca del origen y destino del hombre, filosofía de la historia, naturaleza del Estado y la sociedad. Por sobre esto, sus obras constituyen un llamado de denuncia y advertencia ante el avance incontenible y abrasador del nihilismo como movimiento mundial, a la vez que se convierten en guías para las almas rebeldes ante este proceso avasallador.