Emmanuel Todd

Lineages of Modernity: A History of Humanity from the Stone Age to Homo Americanus

Cambridge, England, and Medford, MA: Polity Press, 2019

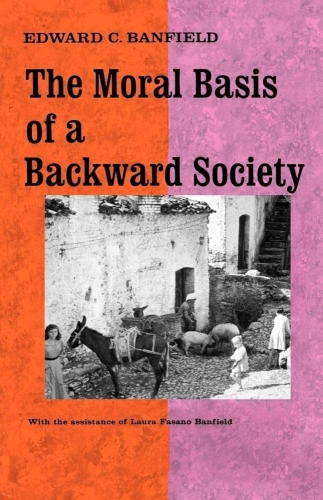

Much of today’s dominant globalist ideology derives from development theory, a body of thought which shares with Marxism the view that economic relations are the basis of social life and sees the races of mankind as fundamentally equivalent beneath the superficial cultural differences which have arisen over history. Human societies everywhere naturally develop from the hunter-gatherer stage to pastoralism, then to settled agriculture, and eventually to modern industrial civilization and “democracy” — the final stage, or at least the highest yet attained. Francis Fukuyama aptly characterized the development theorists’ dream as “getting to Denmark” — a world wherein all nations gradually converge on the model of a prosperous, stable, secure nation of the northern European type. But development occurs at different tempos in different places, with the result that some countries remain “undeveloped” (or, more euphemistically, still “developing”) while others have already reached the highest stage. Those in the vanguard of progress, mainly European-descended peoples, can help the rest develop by means of expertly managed international programs. Not the least important function of development theory, accordingly, is to justify prestige and rewards for a class of globe-trotting program administrators. Yet the world stubbornly refuses to evolve as globalist ideology foresees; plenty of differences remain intractable.

Much of today’s dominant globalist ideology derives from development theory, a body of thought which shares with Marxism the view that economic relations are the basis of social life and sees the races of mankind as fundamentally equivalent beneath the superficial cultural differences which have arisen over history. Human societies everywhere naturally develop from the hunter-gatherer stage to pastoralism, then to settled agriculture, and eventually to modern industrial civilization and “democracy” — the final stage, or at least the highest yet attained. Francis Fukuyama aptly characterized the development theorists’ dream as “getting to Denmark” — a world wherein all nations gradually converge on the model of a prosperous, stable, secure nation of the northern European type. But development occurs at different tempos in different places, with the result that some countries remain “undeveloped” (or, more euphemistically, still “developing”) while others have already reached the highest stage. Those in the vanguard of progress, mainly European-descended peoples, can help the rest develop by means of expertly managed international programs. Not the least important function of development theory, accordingly, is to justify prestige and rewards for a class of globe-trotting program administrators. Yet the world stubbornly refuses to evolve as globalist ideology foresees; plenty of differences remain intractable.

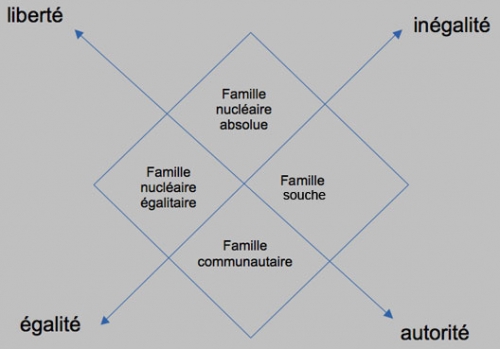

Emmanuel Todd is an anthropologist and demographer who focuses on family systems, an unusual but sometimes enlightening perspective to bring to historical and political questions. In the early 1980s, for example, he pointed out the connection between Leninist communism and a particular kind of peasant family pattern:

. . . a form that combined a father with his married sons, authoritarian as regards the relations between parents and children, egalitarian in the relations between brothers. Authority and equality, indeed, represent the hard core of communist ideology, and the coincidence between family and ideology was not difficult to explain. It resulted from a sequence at once historical and anthropological: urbanization and literacy broke down the communal peasant family; the latter, once it has disintegrated, releases into general social life its values of authority and equality; individuals emancipated from paternal constraint seek a substitute for their family servitude in fidelity to a single party, in integration by the centralized economy.

Todd found this pattern not only in Russia, China, and Vietnam, but also in Serbia (the backbone of Yugoslav communism) and north-central Italy (the region which voted heavily communist in the 1970s). In countries with different family systems — including Poland, the Czech lands, Slovenia and most of Croatia — communism is only likely to prevail for as long as it is imposed by an outside power. I thought I knew a fair amount about communism, but this was new to me.

Deep History

Todd advocates a three-level perspective on the history of nations, with change proceeding at a different pace on each level. At the conscious level we find war, politics, and economic policy. History often proceeds very quickly at this top level. At the subconscious level we find major educational changes such as the spread of basic literacy, which began in Germany with the Protestant Reformation and which Todd expects to reach its completion around the world within the next generation, i.e., over a period of about five hundred years. At the deepest, unconscious level we find religion and family structures, which change even more slowly. The economistic thinking characteristic of globalist ideology mistakes the most superficial level for the most fundamental.

In previous works, Todd has demonstrated that even in fully secularized societies, the religious beliefs of the past continue to influence thinking on an unconscious level. He has, for example, described a “zombie Catholicism” which must be taken into account if one wishes to understand social behavior in the French provinces today. In this work, he finds an analogous “zombie Protestantism” useful for understanding the educational and economic effectiveness of Scandinavia. Furthermore, as he notes,

In previous works, Todd has demonstrated that even in fully secularized societies, the religious beliefs of the past continue to influence thinking on an unconscious level. He has, for example, described a “zombie Catholicism” which must be taken into account if one wishes to understand social behavior in the French provinces today. In this work, he finds an analogous “zombie Protestantism” useful for understanding the educational and economic effectiveness of Scandinavia. Furthermore, as he notes,

It is usually difficult to completely separate family systems from religious systems. Religion generally has something to say about sexuality and marriage, the status of women, the authority of parents, and the equality or inequality of brothers.

Regarding family structure, Todd proposes a model of historical development according to which families tend to become increasingly patrilineal over time,

from the undifferentiated nuclear family (level 0 patrilineality) to the stem family (level 1 patrilineality), then from the stem family to the exogamous communitarian family (level 2 patrilineality), and finally to the endogamous communitarian family (level 3 patrilineality).

It is important to understand that this is not simply a development from worse to better. The higher levels must, indeed, have some advantage over the lower; otherwise, it would be difficult to explain why they developed. But Todd stresses that the more primitive types also have advantages that get sacrificed along the way. The modern economic powerhouses treated as universally normative by development theorists, for example, tend to have what are historically and anthropologically more “primitive” family patterns, while the communitarian family practicing cousin marriage and sequestering its women is the most complex and sophisticated arrangement. Globalists mystified that economically backward Islamic societies do not simply abandon cousin marriage and embrace “modern, progressive” sexual and family norms are in effect expecting several thousand years of historical development to go suddenly into reverse.

The Original Human Family

Early on, Todd offers a description of the original anthropological system of humanity, the “undifferentiated nuclear family,” as an ideal type:

The family is nuclear, albeit without dogmatism — young couples or elderly parents can be temporarily added to it. Women’s status is high. The kinship system is bilateral, giving the mother’s and father’s kin equal places in the child’s world. Marriage is exogamous, but again without dogmatism [i.e., there is no formal prohibition against consanguineous marriage]. Divorce is possible. Polygyny too, and sometimes even, although more rarely, polyandry. Interactions between the families of brothers and sisters are frequent and structure local groups. No relationship is completely stable. Families and individuals can separate and regroup. There are two levels of aggregation above the family:

1. Several nuclear families, most often related, constitute a mobile group.

2. These groups exchange spouses with each other within a territory comprising perhaps a thousand individuals.

Such a primordial human society is fairly tolerant of occasional homosexual or other non-reproductive sexual behavior, but this remains marginal.

Todd’s general descriptor for such flexible arrangements is “undifferentiated.” As he notes, anthropologists have used this term “to describe kinship systems that are neither patrilineal nor matrilineal, but leave individuals free to use paternal and maternal filiations pragmatically.” Todd himself extends the concept “to all elements of the family structure that have not been polarized in the course of history by a stable dichotomous choice.” Todd believes the original undifferentiated family type was universal among Homo sapiens before the rise of cities and writing in ancient Sumer about 5000 years ago.

A family system is undifferentiated in regard to co-residence of generations, e.g., where it occurs temporarily according to convenience without being evaluated either positively (as in the Russian or Chinese peasant family) or negatively (as often in the Anglo-Saxon world). Undifferentiated inheritance is regulated neither in an egalitarian nor an inegalitarian (e.g., with primogeniture) spirit. Polygyny below about the ten percent threshold may be considered undifferentiated; both socially enforced monogamy and polygyny above fifteen percent indicate differentiation. Both the formal prohibition against cousin marriage (as in Christendom) and cousin marriage as a normative ideal (as in the Arab-Persian world) indicate differentiation.

Reading History in Space

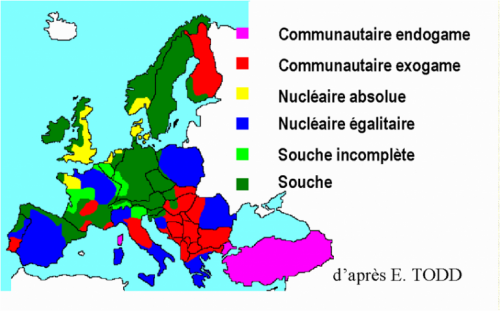

If we look at a map of Eurasian family patterns today, we find that the more central regions display greater patrilineal development, while simpler systems (which also involve a higher status for women) survive on the peripheries. To explain this, the author appeals to a once commonplace linguistic and anthropological interpretive principle that fell out of fashion with the rise of structuralism after the Second World War: the conservatism of peripheral areas.

This powerful explanatory hypothesis makes it possible to read history in space: the most archaic forms (linguistic, architectural, culinary or family) survive on the periphery of cultural spaces. . . . If a characteristic A distinguishes several pockets placed on the periphery of a characteristic B that covers a continuous central space, we can suppose that A represents the ancient characteristic, and B a central innovation that has spread to the periphery without completely submerging it. The greater the number of residual pockets, the more certain we can be of our interpretation.

This is what we find with family patterns on the Eurasian landmass. The Arab-Persian world, Northern India, and China are the classic settings of the Communitarian Family. Northwest Russia shows this type as well, albeit without endogamy and only dating back to the seventeenth century.

The nuclear family model survives in much of Western Europe. In Northeast Asia, it can still be found among relict native Siberian populations such as the Chukchi, as well as the Ainu of northern Japan. On the fringes of South Asia, it survives in Sri Lanka and among the natives of the Andaman Islands as well as the Christians of Southwest India. And it characterizes much of Southeast Asia, including Indonesia and the Philippine Islands. As Todd remarks: “Geography here provides us with the key to history. We can read the effects of time directly in space; we can see the patrilineal shift transforming the shape of the family, moving in waves toward a periphery that is never reached.”

The Differentiated Nuclear Family: England

It is important to note, however, that the nuclear family, where it has survived, has not remained undifferentiated; it now represents a “stable dichotomous choice.” In Europe, as Todd writes, the primordial patterns were “regulated rather than abolished by the Christian conception of sex and marriage.” In Christian England, e.g., undifferentiated de facto monogamy (with polygyny at the margins) was replaced by socially enforced and indissoluble monogamy: the covenantal marriage. Consanguineous marriage was not tolerated; neither were homosexuality or other nonreproductive forms of sex.

Lateral bonds between adult siblings lost all economic functionality. The three-generation household came to be frowned upon: young couples were required to establish their own households at marriage. This had the disadvantage of making it harder to care for the elderly and infirm. To meet the difficulty, the English Poor Laws of 1598 and 1601 required parishes to levy taxes for their support.

A sample of twenty communities, a picture of which can be formed from the parish register and the poor register combined, means we can study 110,000 pensions payments between 1660 and 1740. Statistical analysis reveals that 5 per cent of the population received a weekly pension, a figure that rose to 8 or 9 per cent in the city and 40-45 per cent for the over-sixties. For the latter, the average level of pension corresponded to the wages of a farm worker.

As the author notes, these facts contradict the “textbook commonplace” that Bismarck’s Germany pioneered social security.

Parents were left free to bequeath their property as they saw fit, a system neither egalitarian nor distinctly inegalitarian. English society also came to be characterized by extreme mobility: “Children moved as servants between large farms while still very young. Even the sons of better-off peasants were sent elsewhere as servants under the practice of ‘sending out.’”

Todd calls this system the absolute nuclear family; it was fully formed (=differentiated) by about the mid-seventeenth century. Apart from England, something broadly similar is found in Denmark, Southeast Norway (the Oslofjord), the Protestant and coastal parts of the Netherlands, as well as Upper Brittany in France.

Chaucer’s England was a land of about three million souls on the edge of a Eurasian continent with a population of about 300 million. Many historians have wondered that so tiny a country on the fringe of civilization went on to shape the modern world more than any other. Todd eventually came to the conclusion that England’s peripheral location and the anthropological backwardness that went with it were the secret of its success:

Its dynamism, and even more so that of [its offspring] America, is the dynamism of the original Homo sapiens. Elsewhere, successive civilizations have had time to imprison themselves in complex constructions that are liable to paralyze human creativity.

Encouraging the autonomy of children, the absolute nuclear family fosters individualism and allows major breaks between generations. These were anthropological preconditions for the industrial revolution, which uprooted much of the English peasantry within just a few decades. So there is a definite association between economic progress and anthropological “backwardness.” Todd devotes a chapter to demonstrating that democracy (or, perhaps better, participatory government) is primordial as well: “the rise of complex family forms corresponds to the rise of authoritarian political forms.”

The Stem Family and Literacy: Germany

Given the advantages of the nuclear family, one may ask why it was ever superseded. The answer is that in the preindustrial world wealth derives mostly from the possession of land, and as population increases, land eventually becomes scarce. If a farmer has many children and divides his land between them, the plots will eventually become too small to support new families. To avoid such a result, primogeniture is instituted:

Male primogeniture makes it possible to transmit real estate without dividing it. The emergence of a densely settled rural world crowned by a political system that controls the whole of the regional space, is the basic condition for it to emerge. As long as there are new lands to be conquered, the emigration of children when they reach adulthood renders the privilege of the eldest useless. When land becomes scarce, this privilege may appear. The stem family then develops as a logical consequence of primogeniture: the choice of a single heir gradually leads to the co-residence of two adult generations.

Primogeniture and the stem family represent the first stage of patrilineality and, as compared to the nuclear family, tend to promote the values of authority and inequality. Younger sons must find their own way in the world.

Historically, this pattern first emerged from the undifferentiated nuclear family in Sumer not long after the invention of writing in 3300 BC. Skipping over antiquity, primogeniture arose in European history toward the end of the Carolingian period, with the founding of France’s Capetian monarchy among its first consequences. The institution subsequently spread through Europe’s aristocracy from the eleventh century. It arrived in England with the Conquest, but there remained the preserve of aristocrats. Yet primogeniture also emerged independently in peasant communities in Germany and Southern France beginning in the thirteenth century, also from a scarcity of land. Todd mentions that the German aristocracy distinguished itself from commoners by their practice of egalitarian inheritance — the reverse of the pattern in England.

The stem family was an essential component of a triple revolution that began in Germany and which, in Todd’s view, represents that nation’s single most important contribution to European and world civilization. The other two components of this revolution were Protestantism and universal literacy.

The author points out a commonality between primogeniture and writing: they both serve the purpose of transmission:

Writing is, in essence, a knowledge-fixing technique that allows human society to escape the uncertainty of oral transmission of memory. Primogeniture, with the stem family that ultimately stems from it, is also a technique of transmission: it transmits the monarchical state, the fief, peasant farming, the artisan’s stall and, at a deeper level, all the techniques that accompany these elements of social structures.

The gradual development of the stem family in Germany can be traced in the historical record between the fourteenth and eighteenth centuries. In about 1454, printing with moveable type was invented by the German Gutenberg, leading to a drastic reduction in the cost of reproducing texts. After 1517, Martin Luther launched the Protestant Reformation which, from the beginning, “sought to establish, for each human being, a personal dialogue with God, without the mediation of the priest.” This meant that responsibility for religious instruction passed to fathers:

Luther’s Little Catechism, the first vehicle of the Protestant educational offensive, displays, right from the start, an unambiguous patriarchal familialism: “The Ten Commandments or the Decalogue, Such as a father of a family must teach them with simplicity to his children and his servants.” It is easy to see how the father’s authority would be reinforced by his new religious role in the family.

Todd even asserts a fundamental connection between the stem family and the specifically theological content of Protestantism:

The mechanism that leads from family organization to religious system is simple; primogeniture comes with a high level of authority in the father; it defines a son who is chosen and other children who are rejected. In such a domestic context, a theological system that affirms that the Everlasting predestines a minority to salvation and the rest of humankind to damnation can appear quite simply as normal. It should be noted that when Protestantism spread from stem-family areas toward regions where the absolute nuclear family dominated, its dogma of predestination eventually collapsed.

As is well-known, the reformation focused on making the Bible available to ordinary people in their national vernaculars. At first, this occurred principally through church services and sermons, but in the course of the seventeenth century, literacy and Bible reading began gaining ground among the masses. By 1700, an estimated 35-45 percent of the population of Protestant Europe could read. This was something new in world history: in the Graeco-Roman world, according to the most careful modern estimates, male literacy rarely exceeded twenty percent anywhere.

The Great European Mental Transformation

One of Todd’s best chapters is devoted to “The Great European Mental Transformation” which resulted from the spread of literacy:

We would be wrong to see learning to read as merely the acquisition of a technique. We are now beginning to measure the enlargement of the brain function induced by an intensive and early use of reading. Reading creates a new person. It changes one’s relationship to the world. It allows a more complex inner life and achieves a transformation of the personality.

According to sociologist David Riesman (The Lonely Crowd, 1950), reading provides the old human personality regulated by custom with a new type of internal guidance system; he may have been getting at something like the anthropological distinction between shame and guilt cultures. More specifically, Riesman writes: “The inner-directed man often develops a character structure which drives him to work longer hours and to live on lower budgets of leisure and laxity than would have been deemed possible before.” Hence, the Protestant work ethic. The spread of literacy also coincided with a significant fall in private violence.

Such self-discipline also carried over into the realm of sex. Historical research into marriage in Protestant countries during the early modern period reveals both a notable increase in age at first marriage and a larger number of permanently unmarried people. In the author’s view, it was Protestantism that finally fulfilled “the old project of sexual abstinence developed more than a thousand years [before] by the Fathers of the Church.” In the Middle Ages, disciplined celibate religiosity had been the preserve of monastic specialists — religious virtuosos, as Max Weber called them — while the surrounding society remained “bawdy and violent.” Protestantism did not so much abolish the priesthood as clericalize the laity. An important result was lowered population pressure which, combined with the industrial revolution, allowed for an unprecedented accumulation of wealth and rise in living standards.

Todd speaks of a Protestant personality profile: “turned in on itself, predisposed by its morality (sexual or otherwise) to feelings of guilt, to leading an honest and upright life, an essentially active life turned towards study and work.” But he also notes that the Protestant surplus of interiority was compensated by a greater community and state hold over the individual: “The concrete life of Protestant communities, from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century at least, also displays an incredible strengthening of the local group and its ability to control the lives of individuals. The Reformation resulted in a reinforced surveillance of manners.” These are the “moral communities” which Kevin MacDonald has written about as substitutes for the kinship group in individualistic societies.

This era was also characterized by such negative phenomena as religious hatreds, the rise of absolutism, and a recrudescence of war: “the price to be paid for the internal pacification of behavior was a collective reorientation of violence.” Stem family Protestant countries in which younger sons had to fend for themselves pioneered standing armies and militarism. Louis XIV is generally considered a warlike king, but at their height in 1710, his forces enrolled only 1.5 percent of Catholic France’s population. Around the same time, the Swedish Empire of Charles XII was employing 7.7 percent of its population in the military. By 1760, 7.1 percent of Prussia, that “army with a country attached,” was in uniform. Hesse, whose soldiers made up the bulk of British forces during the American War of Independence, practiced a mercenary militarism with the goal of increasing state revenue; by 1782 they had matched the Swedish figure of 7.7 percent of the population under arms. In some stem family Protestant countries, younger sons were automatically enlisted upon coming of age.

It remains to speak of the relation of the stem family to the industrial revolution which, as we have seen, was pioneered by a nation with an absolute nuclear family. Firstly, we should mention that literacy is the single most important factor in industrialization, and we have seen that the ideal of universal literacy was one third of a revolution whose other aspects were the stem family and Protestantism.

But the stem family, being essentially a system of transmission, also has a certain conservative tendency. We find such areas resisting industrialism for a time:

A society based on the accumulation of what has been acquired is endowed with the capacity for making any progress that does not entail a radical change in its methods and objectives. For example, it will be more difficult to transform rural people into urban people, artisans into factory workers, or nobles into entrepreneurs. The uprooting and transformation of all these actors can only be brought about under external pressure, and at the cost of great pain.

Of course, the rise of Britain did put pressure on other European nations. The most important stem family nation, Germany, experienced a delayed and highly disruptive transition to industrial capitalism. Once that transformation had occurred, however, the stem family acted as an accelerant: by the beginning of the twentieth century, Germany had actually overtaken Great Britain economically. We might also mention that Japan, a stem family society on the opposite side of Eurasia, went through a similar process during the Meiji period.

Secularization and Ideological Crisis

Another central tendency of the modern era on which light can be shed by the study of family structures and the spread of literacy is secularization. At first, of course, the Protestant Reformation amounted to a religious revival, as did the Catholic Counter-Reformation. Todd, however, interprets puritanism — a kind of radicalized Protestantism — as a “stiffening of the faith” which marks “a step on the path to secularization.”

It was the Paris Basin of Northern France which witnessed “the first religious collapse of a ‘sociological’ magnitude.” Between 1730 and 1740, the recruitment of priests collapsed. Subsequently, both religious observance and the birth rate declined among the masses of Northern France. This process was complete well before the French Revolution.

The family structure of the Paris Basin is an egalitarian variant of the nuclear family wherein parents are expected to divide their property equally between all children. Unlike in the stem family areas,

there was no strong image of the father to prop up the image of God; and there was no inequality between children to justify inequality between the priest and the ordinary person. In such an environment, the shock of rationalism was not cushioned by a deeply rooted belief. In fact, the principle of equality. . . seemed destined to call into question the belief in a superior being of any kind — father, king, or God.

The French Revolution was the result of a long development involving the spread of literacy, secularization, and falling birth rates, as France’s Annales historical school has uncovered.

Although France was the most historically important center of this first wave of secularization, it also affected other areas with a similar family structure:

In Southern Europe, with its egalitarian nuclear families, literacy at this time affected only the urban world, which around the middle of the eighteenth century lay outside the grip of the Church. Because the cities were feeding the countryside with a flow of religious personal, which then dried up, [not only] the Paris Basin [but also] Andalusia and southern Italy entered this new phase . . . [of] secularization.

The apostasy of these egalitarian areas strongly affected the Catholicism which survived into the nineteenth century, largely dependent on stem family regions: the church became a bastion of hierarchy and respect for every sort of authority. As the author notes, this mentality is far removed from that of early Christianity in the Late Roman Empire.

The second round of European secularization occurred in the Protestant lands beginning in the late nineteenth century:

In Calvinist and Lutheran Europe, secularization did not begin until the publication of The Origin of Species. The subsequent collapse was a brutal affair in a world heavily dependent on a literal interpretation of the Bible. Between 1870 and 1930, throughout Northwest and Northern Europe, the recruitment of Protestant pastors collapsed. Secularization was finally hitting the most educated part of the continent. It opened up a phase of maximum ideological instability.

Generalizing from the work of the Annales school, Todd proposes a regular pattern of historical development running from literacy to secularization to a declining birth rate to an ideological crisis and revolution. The ideological crisis which followed the collapse of Protestantism in Germany was not, however, the rise of socialism, heir apparent of France’s revolution:

Socialism took an essentially reformist and reasonable form . . . in Protestant Europe. It was the rise of nationalism that eventually dragged the continent into the conflagration of the First World War. It is obvious that the epicenter of the ideological and mental crisis lay in Germany.

National Socialism was also, in Todd’s view, a consequence of the crisis of German Protestantism. Support for the NSDAP always remained weak in Catholic areas of Germany, despite the party’s Bavarian origins. The author dismisses explanations that focus excessively on the Great Depression as a product of superficial economistic thinking. The deeply authoritarian yet non-egalitarian character of National Socialist ideology Todd explains by Germany’s stem family structure, so different from the egalitarian nuclear family system of Northern France (as well as the egalitarian communal family of Russia).

The Memory of Places

The family forms Todd discusses all arose before industrialization, and in a sense clearly belong to the past: there are no more three-generation households in Berlin today than there are in London; fathers do not co-reside with the families of all their grown sons in today’s Moscow any more than in the US. Nuclear households characterize these formerly stem- and communal-family areas no less than the Anglo-Saxon world. Might this represent a “convergence” such as globalists dream of?

Todd does not believe so. He stresses the distinction between

the family system — i.e., a set of values organizing the relationships between men and women, between parents and children, between brothers and sister — and the domestic group as can be seen in the census. It is quite conceivable that a system of values may survive the disintegration of the domestic group in which it was embodied in the peasant era. The nuclearization of households does not necessarily imply that of mentalities.

Mentalities can prove astonishingly stable even amid radical social change. An important example is the persistence of regional cultures. In 2013, Todd and the demographer and historian Hervé Le Bras collaborated on a book documenting

the perpetuation, across 550,000 square kilometers of France, of different systems of customs and manners in most recent times. Despite the acceleration of internal migration, despite the disappearance of complex households and the collapse of Catholicism, regional heterogeneity persists. Homogenization, via television, the TGV express train, and the Internet has not prevented the persistence of diverse cultures, stimulated rather than erased by economic globalization. And all this has happened within a single nation, unified by administration and language.

Todd calls this phenomenon the “memory of places.” His explanation for it is that even values weakly held at the individual level and transmitted through the most casual mimetic processes can produce extremely strong, resilient, and sustainable belief systems at the group level. Such an interpretation also helps us to understand the persistence of national temperaments without our having to assume that everyone is the incarnation of an immutable national archetype or Volksgeist.

Todd calls this phenomenon the “memory of places.” His explanation for it is that even values weakly held at the individual level and transmitted through the most casual mimetic processes can produce extremely strong, resilient, and sustainable belief systems at the group level. Such an interpretation also helps us to understand the persistence of national temperaments without our having to assume that everyone is the incarnation of an immutable national archetype or Volksgeist.

The author offers an amusing illustration of how notions weakly held at the individual level can persist in groups: in the 1990s, he found it easy to convince people privately of the absurdity of the project for a single European currency.

But the belief in the inevitability of the euro was invulnerable at the collective level. The weak belief was already carried by a sufficiently broad group, and the individual, convinced for a while, returned to his or her belief at the same time as to his or her milieu after the conversation.

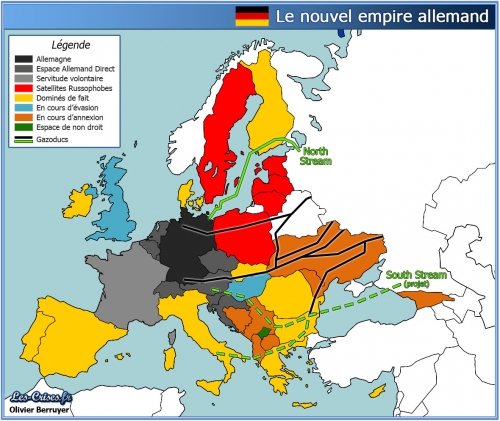

Stem Family Regions Today: The Case of Germany

Todd uses the concept of the memory of places to explain certain aspects of postwar German economic behavior which cannot be accounted for by economic theory itself. German consumers are more likely than those of the English-speaking world to prefer domestic products. German managers are less interested in short-term profit maximization than the long-term viability of their companies. Germany maintains a trade surplus while Anglo-Saxon countries cheerfully heap up debt. And more than other Western nations, the German economy relies on

small and medium-sized companies that dominate a narrow niche of global production, and prefer to develop their product or their range rather than to diversify. These companies are often located in areas that cannot be described as urban, and they continue, where possible, to prefer family transmission. They preserve the memory of primogeniture.

In the generation since reunification,

Germany has rebuilt its eastern area ruined by communism; it has reorganized Eastern Europe, putting to work the active populations brought up under the old popular democracies; in the West, it has conducted a real industrial blitzkrieg against the weaker nations trapped in the euro; it is proposing a partnership with China and posing as the economic rival of the United States.

All of this testifies to a continued German national consciousness and capacity for collective action, traceable to the stem-family mentality. This is all the more remarkable in that it can never be mentioned. Officially and publicly, the country operates on the assumption that the concept of nationhood was first introduced to the world by Adolf Hitler in 1933, so that any explicit national considerations are sufficient to mark one out as a “Nazi.” What we observe in Germany is a “zombie nationalism,” continuing at an unconscious level in spite of the country’s strict anti-national orthodoxy.

But all is not well in Germany. Todd observes that the birth rate in nuclear family regions of the West has remained reasonably close to replacement level at around 1.9 children per woman. In stem family areas it trends considerably lower, and is down to 1.4 in Germany. Todd ascribes this demographic disaster to

a mismatch between stem-family values and the ultra-individualism that has come from the West. In Germany, there is a widespread feeling that caring for a child full time is a moral obligation for the mother. Such a conception is not very compatible with the notion of a career. The level of state childcare provision is therefore low in the Federal Republic. But institutions here are simply reflecting mentalities.

German women have, indeed, increasingly opted for careers since the Second World War, but are more likely to remain entirely childless than their counterparts in France and the Anglosphere.

The eastward expansion of the EU and the recent departure of the United Kingdom have resulted in an EU dominated by its stem family areas — which include Germany, of course, but also the 47 percent share of the stem family population which lies outside the German-speaking world. This has given today’s EU a distinctly more inegalitarian and authoritarian cast than its founders intended:

A hierarchy of nations, more or less rich, more or less powerful, more or less dominated, has appeared. Nothing about this system is an accident. The political, economic, and social system that has developed in Europe with its hierarchy of peoples, its economic inequalities, and its absence of representative democracy, is the normal form to which the stem family must give birth.

Communitarian Family Regions: Russia and Belarus

Besides nuclear and stem family forms, three regions in Europe developed exogamous communitarian families in which adult brothers and their families co-reside with the family patriarch. Such a system represents the second level of patrilineal development in Todd’s scheme. One such region is North Central Italy, including Tuscany, Umbria, and Emilia-Romagna where, as we have mentioned, support for the Italian Communist Party used to be quite high. A second communitarian family zone stretches from the Balkans into central Europe, including Bulgaria, Albania, most of the non-Catholic constituents of the former Yugoslavia, as well as Slovakia and parts of Hungary. Todd says relatively little about this area.

The third communitarian family region includes Northwest Russia, Belarus, and the Baltic States. This area developed the communitarian family relatively recently, between the seventeenth century and the abolition of serfdom in 1861. Todd suggests the system may have been “born of a confrontation between the Germanic stem family and Mongolian patrilineal organization.” It is unusual among communitarian regions in maintaining a relatively high status for women (such as is not found in the Balkans, for example). The communitarian family system of Northwest Russia was historically important in providing a sociological basis for Russian communism, as explained near the beginning of this review. In the 1917 elections to the Constituent Assembly, the Bolshevik Party gained only 24 percent of the vote over the whole of the Russian Empire, but achieved over 50 percent support in St. Petersburg, Moscow, and Belarus. In Livonia, a region that included parts of today’s Latvia and Estonia, its share of the vote rose to 71 percent.

Even today, after all the upheavals of the twentieth century, this family background can explain certain aspects of political behavior which mystify outsiders:

The permanence of communitarian values obviously explains the emergence, after the disorder of the 1990s and 2000s, of a stable authoritarian democracy, combining elections and an unanimist vote. Indeed, there is nothing in the electoral process to prevent Vladimir Putin being indefinitely re-elected to head the system. Control of the media is not the fundamental cause of permanence in power; authoritarianism is rooted in the people, and draws on communitarian values that are constantly being reproduced by the memory of places.

The memory of places [also] provides us with the fascinating example of Belarus that today is more attached than Russia to authoritarianism. Pres. Lukashenko is now the only “old-fashioned” dictator on the European continent, but the citizens of Belarus seem perfectly happy with the situation — and their society is functioning quite satisfactorily.

Putin’s Russia has instituted a protectionist regime to allow the reconstruction of the country’s industrial base. This amounts, as the author explains, to a “refusal of the Russian ruling class to see the people sold off as a cheap labor force to globalized capitalism,” and this is something the West’s neo-liberal elites cannot forgive. Poor as it is, Russia “remains a counter-model in a world that has moved towards a fierce ultra-individualism.” It also preserves a strong national consciousness without any of the embarrassment that affects Germany:

The values that have emerged from the communitarian family ensure the persistence of an integrated concept of the nation. The almost familial, concept of the people [narod] that characterizes Russia prevents Moscow from fantasizing about the dissolution of nations. In a world where most nations are small and militarily insignificant, the allure of the Russian approach is obvious, and very exasperating for the American geopoliticians who still think in terms of being all-powerful.

The best proof of the essential healthiness of today’s Russia can be found in demographic statistics. We may note here that Todd first gained notoriety back in the mid-1970s for predicting the impending collapse of Soviet communism on the basis of its rising infant mortality rate, something that had escaped everyone else’s attention. After reaching 22 per 1000 live births in the 1990s, infant mortality began to sink sharply around 2003 and now stands at 7 per 1000 (in Belarus, the figure is 3.6, comparable to Western Europe). Russia has recently experienced a drop of 53 percent in the suicide rate (2001-2014), 71 percent in the homicide rate (2003-2014), and 78 percent in the alcohol poisoning rate (2003-2014).

A revealing large focus of anti-Russian agitation in the West today involves Russia’s so-called homophobia. Todd suggests the West may be shifting away from the nuclear family model in favor of an extreme individualism in which people are conceived of as monads “detached from the conjugal family [and] ideally embodied by the homosexual of either sex” (for whom a redefined “marriage” is now understood as a right rather than, as traditionally for men and women, a duty). Russia, meanwhile, after undergoing a disastrous fall in its birth rate during the late 1980s and 1990s, has rebounded to 1.8 children per woman, well above the European average. In 2008, the Russian Orthodox Church even introduced a new holiday, the “Day of Family, Love, and Faithfulness,” as a celebration of natural procreation. No wonder the West hates them!

Russia fills an important role on the international stage today by offering an alternative to the Anglosphere’s combination of globalism, liberal economics, and maladaptively exaggerated individualism: it stands for a multipolar world of independent sovereign nations.

Mass Immigration and the Clash of Family Systems

Europe, then, is characterized by three fundamental family types: nuclear, stem, and exogamous communitarian. But let us recall that Todd distinguishes a fourth type: the endogamous communitarian family. This variant idealizes cousin marriage and frequently involves polygyny and purdah, or the systematic sequestration of women. Until very recently, such practices were entirely absent from Europe; today, of course, mass immigration has introduced them. Todd, although a man of the Left, is sensible enough to describe this development as “a bridge too far.” “The memory of places requires limited flows of migrants for it to function,” he cautions; “The arrival in just a few months of a block of immigrants is a quite different phenomenon.”

Of Angela Merkel’s lawless decision to open Germany’s borders in the summer of 2015, he observes:

Of Angela Merkel’s lawless decision to open Germany’s borders in the summer of 2015, he observes:

With the family reunifications that will follow, we can predict with absolute certainty the stabilization and growth of a separate population living in parallel with the [pre-existing] Turkish group. We must therefore imagine a Germany increasingly concerned about its internal stability and cohesion. The real risk is that of the internal hardening of a German society in which anxiety leads to a policing of the different ways of life.

To us, the real risk would seem to be something a great deal worse than this, and affecting not only Germany but our entire civilization.

Biology Denial

Thus far, we have had little but praise for Todd’s vision of a deep level of history where “anthropological substrata impose their values without the knowledge of the actors.” Yet we must note one essential limitation: he refuses to descend from the anthropological to the biological level. Early on, he claims that genetic analysis “in most cases . . . does not go much further than the examination of trivial phenotypic differences such as skin color or facial features.” It is tempting to counter that picking up a book such as The Bell Curve might have relieved the author of such a misapprehension. Alas, he reports: “I read this book when it first came out, and it sickened me.” Elsewhere he refers to IQ researchers as “ideologues.”

This blindness is all the odder in that biology represents, even more than anthropology, a deep, unconscious level of history whose study can bring to light otherwise invisible constraints under which the games of international relations and economic policy are played out. It would seem to be the next logical step on the path Todd has taken throughout his professional life.

In practice, the errors into which the author’s refusal to confront biological reality leads him seem mainly to affect his interpretation of very recent history, particularly 1) the higher education revolution since the Second World War, and 2) the third and final wave of secularization affecting areas where Catholicism remained strong until the 1960s.

The Secondary and Higher Education Revolutions: America

The popular spread of literacy which began in Protestant Germany can be seen in retrospect as a first educational revolution. In twentieth-century America, it was followed by what Todd considers a second and third educational revolution involving secondary and higher education respectively.

In 1900, ten percent of young Americans attended high school; six percent graduated. By 1940, 70 percent of Americans were attending high school and fully half of them completing it. Todd believes this rapid expansion of secondary education revolution was in part responsible for the New Deal and declining economic inequality between the 1920 and 1970s. The expansion continued after the war until, by the 1960s, “dropouts” (a term coined at this time) came to be seen as failures. The US was the undisputed leader of the movement to universalize secondary education: in the mid-1950s, when 80 percent of American 15-19 year olds were in education, the corresponding figures for Britain, France and West Germany hovered between 15 and 20 percent. Todd comments:

The second educational revolution was driven by an ideology of a democratic and egalitarian hue. American education was liberal, open, and concerned with the development of the individual as much as the acquisition of knowledge. This educational system showed absolutely no interest in elitist performance. It enabled the assimilation of immigrants [and] thus contributed to the emergence of an America that was not just prosperous but also culturally homogeneous.

In its egalitarian and homogenizing effects, this revolution was similar to the first educational revolution universalizing basic literacy.

The third educational revolution involved higher or tertiary education. Although historically it followed closely upon the expansion of secondary education and was motivated by the same ideals, Todd treats it as a separate phenomenon because of its association with inequality and social stratification.

On the eve of the Second World War, 7.5 percent of America’s men and 5 percent of its women earned Bachelor’s degrees. Following the war and passage of the GI Bill, higher education began expanding rapidly. Within a generation, by 1975, 27 percent of men and 22.5 percent of women were completing college. “Once these levels had been attained,” the author writes, “the model of ever-increasing education for all—applicable almost perfectly to primary and more or less to secondary education — lost its validity.” Higher education plateaued in the 1970s and 80s, and Todd recognizes that this “did not result from any restriction by the host system but from the fact that an intellectual ceiling had been reached.” Rather, “higher education is, by its nature, stratified.”

Misreading Contemporary Inequality: Higher Education and Neo-Liberalism

So far, so good. To a biological realist, it is obvious that the indefinite expansion of education was always a utopian project bound to crash into the wall of natural and inherited capacities, intelligence in particular. Todd’s reference to an “intellectual ceiling” seems to imply a recognition of this. Yet he then turns around and treats so knowledgeable authority on intelligence as Richard Herrnstein as an “ideologue . . . embarked on the theoretical shaping of a new inegalitarian creed” meant to justify social and economic inequality!

It may be that Todd accepts intellectual differences at the individual level but not the group level, or it may be that he simply has no consistent position; his statements remain ambiguous or contradictory. But he clearly affirms that the higher education revolution has produced inequality rather than merely revealing it; one of his chapter subsections is actually entitled “Academia: a machine to manufacture inequality.”

Each institution of higher education assigns each student a place in the social hierarchy. Knowledge is of course transmitted there, and research carried out. However, since studies are now longer than required for the acquisition of knowledge or the identification of aptitude for research, it is clear that the hierarchization of society has become the primary goal.

And he maintains that the rise in economic inequality since the 1980s has been a consequence of this educational system, although all he demonstrates is that, historically, one followed the other; in other words, he may be guilty of the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy. I share Todd’s disdain for an economic system that has “forced American workers to compete with Third World workers who were paid twenty or thirty times less,” even as CEO salaries at Fortune 500 companies have risen from 20 times that of the average worker in 1950 to 204 times in 2013. But the natural inequalities increasingly revealed in educational achievement were just as real before this change in policy came about, and will remain with us under any possible educational or economic system.

Todd makes the valid point that the American revolution in higher education, which has since spread throughout the West,

impose[s] on the participants an attitude of submission to authority [and] nourishes a higher class which, because it is selected by merit, thinks of itself [as] intellectually and morally superior. This superiority is a collective illusion: the homogeneity and conformism engendered by the mechanism of selection produces the ultimate paradox of a ‘world above’ subject to intellectual introversion, unsuited to individual thought.

But the illusion is not that differences in natural aptitude for higher education exist; it is that today’s hypertrophy of professional and technical training is equivalent to an increase in education as such. I can only shake my head over the presumption of equivalence between the number of years people now spend in school and their intellectual and (especially) moral development. It should be obvious that neither the individual nor society gains much from any increase in the number of doctorates awarded in “early childhood education” or “resentment studies,” but such bogus programs of study were a nearly inevitable consequence of trying to expand higher education past the point of diminishing returns determined by the fixed factor of inherited natural aptitude.

In such an academic environment, the ideal of liberal education — i.e., the cultivation of the mind for its own sake — cannot survive. And it is a proper liberal education, especially, which can teach intellectual humility to the highly intelligent. Hence the degeneration of higher education into the combination of professional training and political indoctrination we see today. And hence our current elite consisting of admittedly high-IQ persons who mistake their cleverness and academic qualification for breadth of mind, depth of insight, and even moral superiority.

Our political and social elites badly need replacing, and our bloated and corrupt academy badly needs both extensive pruning and qualitative curricular change. But Todd does not succeed in demonstrating that the higher education revolution is responsible for the harmful effects of neo-liberal economic policies.

The Third Ideological Crisis of Secularization: Is Le Pen a Nazi?

In the 1960s, Catholicism began to collapse in the areas — mainly stem family areas — of Europe where it had survived the first two waves of secularization. Much of the mentality and many social practices associated with Catholic Christianity remain strong in such areas, and this is the context in which Todd developed his concept of “zombie Catholicism.” But specifically religious belief and practice is nearly as vestigial there today as in other parts of Europe. And we may recall that Todd has asserted a natural pattern of development leading from literacy, to secularization, to a declining birthrate and ideological crisis. “Zombie Catholic” areas, like other stem family areas, have been especially hard hit by recent demographic collapse. Can we expect an ideological crisis in these areas as well?

This is not a question of merely theoretical interest, for we may recall that the first wave of secularization was associated with the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, while the second wave was associated with two world wars and German National Socialism.

Todd’s treatment of this theme is coy and extremely compressed, being mostly limited to a couple of sentences. But they are revealing:

Since the mid-1960s, the zones of Catholicism have been living through the final stage of European secularization. And again, the metaphysical emptiness this entails is leading, against a backdrop of economic instability, to great anxiety and to the identifying of scapegoats.

Now, the Left’s favored way of explaining opposition to replacement-level immigration is to interpret it as a “scapegoating” of immigrants driven by economic and other anxieties on the part of irrational bigots. Todd’s free use of the cant expression “Islamophobia” suggests sympathy for this view as well. He appears to be suggesting that the identitarian movement which has arisen in Europe in response to the threat of demographic replacement represents the ideological crisis of the third wave of secularization. This would seem to imply that he considers its destructive potential comparable to that of the French Revolution and the World Wars.

By characterizing the ideological crisis of the second (Protestant) wave of secularization as a “rise of nationalism,” Todd also suggests a historical analogy between the rise of Hitler and today’s “nationalist” opposition to multiculturalism and the Great Replacement. But nationalism is a highly ambiguous term that has meant widely differing things in various historical situations. Today’s nationalism is largely a defensive response to an aggressive globalism that threatens the continued survival of any recognizably Western civilization. It would be either stupid or dishonest to equate it with Hitler’s 1939 invasion of Poland. I cannot help but think that Todd’s Jewish identity has influenced him to seek historical analogies where none exist.

Todd thus follows a pattern I have observed in a depressing number of scholars: he is a learned and original interpreter of the past who quickly turns into a cliché-ridden progressive journalist the moment he turns his attention away from his area of specialization toward questions of contemporary politics.

This does not, of course, negate the value of his scholarly work or diminish the truth of his book’s principal message: mankind is not converging; history is continuing, and its deeper levels will always generate differences in mentality and social behavior that may lead to conflict. As he puts it in the conclusion of his study: “We urgently need to accept the divergence of nations resulting from the differentiation of family systems, if we have the peace of the world at heart.”

If you want to support Counter-Currents, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [4] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [5] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

La version la plus forte et la plus emblématique du vaticanisme est le jésuitisme. Les Jésuites sont nés en tant que bras armé de la papauté à une époque de crise pour le Saint-Siège. Le jésuitisme est cette pratique dans laquelle l'habileté diplomatique du Vatican oriente les "tendances" de la société par des choix politiques et sociaux qui solidifient la relation structurelle entre l'Église et l'État. Voyez en ce sens comment un pape jésuite comme Bergoglio est étroitement lié à la vague de néo-humanitarisme progressiste et actionniste de notre époque.

La version la plus forte et la plus emblématique du vaticanisme est le jésuitisme. Les Jésuites sont nés en tant que bras armé de la papauté à une époque de crise pour le Saint-Siège. Le jésuitisme est cette pratique dans laquelle l'habileté diplomatique du Vatican oriente les "tendances" de la société par des choix politiques et sociaux qui solidifient la relation structurelle entre l'Église et l'État. Voyez en ce sens comment un pape jésuite comme Bergoglio est étroitement lié à la vague de néo-humanitarisme progressiste et actionniste de notre époque. Sous prétexte d'amour parental, la phrase "Roba mia, vienitene con me" du personnage de Mazzarò tiré de la plume de Giovanni Verga dans la nouvelle "La Roba" est fréquemment dissimulée. Mazzarò est un propriétaire terrien, maintenant un vieil homme, qui est sur le point de mourir et qui, n'acceptant pas de perdre tout ce qu'il a eu de sa vie, commence à tuer les canards et les poulets qu'il possède avec son bâton, en disant "Roba mia vienitene con me" . Un exemple typique d'un ego réactif et robotique.

Sous prétexte d'amour parental, la phrase "Roba mia, vienitene con me" du personnage de Mazzarò tiré de la plume de Giovanni Verga dans la nouvelle "La Roba" est fréquemment dissimulée. Mazzarò est un propriétaire terrien, maintenant un vieil homme, qui est sur le point de mourir et qui, n'acceptant pas de perdre tout ce qu'il a eu de sa vie, commence à tuer les canards et les poulets qu'il possède avec son bâton, en disant "Roba mia vienitene con me" . Un exemple typique d'un ego réactif et robotique.

FH – Es la cuestión planteada en Un Mundo Feliz de Aldous Huxley: si tenéis un hijo por la vía sexual es sencillamente porque os habéis ido a la cama con una mujer. Esto no ofrece garantías sobre vuestras cualidades reproductivas ni sobre vuestras competencias como educadores. He aquí por qué sería mejor, para el bienestar del nuevo ser creado, ser puesto a punto dentro de una incubadora y educado por especialistas. Esta argumentación es muy fuerte.

FH – Es la cuestión planteada en Un Mundo Feliz de Aldous Huxley: si tenéis un hijo por la vía sexual es sencillamente porque os habéis ido a la cama con una mujer. Esto no ofrece garantías sobre vuestras cualidades reproductivas ni sobre vuestras competencias como educadores. He aquí por qué sería mejor, para el bienestar del nuevo ser creado, ser puesto a punto dentro de una incubadora y educado por especialistas. Esta argumentación es muy fuerte.

.jpg)

.jpg) zurück schrieb Callonge: »Ich will ins Haus zurück, nicht immer nur erzwungenermaßen, sondern öfter, länger, freiwilliger. Ich will nicht meine Kinder nur zwei Stunden täglich sehen. Ich weigere mich zu wählen zwischen Beruf und Familie. Ich will beides. Ich will leben!« Dieses Buch hatte in Frankreich der Diskussion um die Befreiung der Frau bereits vor dreißig Jahren entscheidende neue Impulse gegeben.

zurück schrieb Callonge: »Ich will ins Haus zurück, nicht immer nur erzwungenermaßen, sondern öfter, länger, freiwilliger. Ich will nicht meine Kinder nur zwei Stunden täglich sehen. Ich weigere mich zu wählen zwischen Beruf und Familie. Ich will beides. Ich will leben!« Dieses Buch hatte in Frankreich der Diskussion um die Befreiung der Frau bereits vor dreißig Jahren entscheidende neue Impulse gegeben..jpg) wie DER SPIEGEL, DIE WELT oder die Süddeutsche Zeitung die Feministin Badinter derzeit ebenso emphatisch hochjubeln wie ihre deutschen Mitstreiterinnen Dorn oder Schwarzer –

wie DER SPIEGEL, DIE WELT oder die Süddeutsche Zeitung die Feministin Badinter derzeit ebenso emphatisch hochjubeln wie ihre deutschen Mitstreiterinnen Dorn oder Schwarzer –  Kinder und Jugendliche sind unsicher und ängstlich wie nie: Alle Umfragen und Studien der zurückliegenden Jahre signalisieren: Kinder und Jugendliche fürchten sich vor der Zukunft!

Kinder und Jugendliche sind unsicher und ängstlich wie nie: Alle Umfragen und Studien der zurückliegenden Jahre signalisieren: Kinder und Jugendliche fürchten sich vor der Zukunft! Der kanadische Psychologe Gordon Neufeld geht davon aus, dass eine starke Gruppensozialisation bei Kindern und Jugendlichen auch Auswirkungen auf das spätere Verhalten im Erwachsenenalter hat: Wer sehr jung die Gruppe als Lebensrealität empfunden und kennen gelernt hat, und wem die Erfahrungen des Alleinseins, aber auch die einer Familie und dem damit verbundenen Zusammenhalt fehlen, der verlässt sich später auch nicht auf sich allein. Extreme Erscheinungsformen der Gleichaltrigenorientierung sind nach seiner Meinung tyrannisierendes Verhalten mit Gewaltanwendung, Selbstmorde und Morde unter Kindern und Jugendlichen. Auch die inzwischen allseits bekannten Massenpartys mit Höhepunkten wie Koma-Sauf-Wettbewerbe oder Gang-Bangs, also Massenvergewaltigungen, bei denen die Mädchen vorher zustimmen, können zu diesen Folgen zählen.

Der kanadische Psychologe Gordon Neufeld geht davon aus, dass eine starke Gruppensozialisation bei Kindern und Jugendlichen auch Auswirkungen auf das spätere Verhalten im Erwachsenenalter hat: Wer sehr jung die Gruppe als Lebensrealität empfunden und kennen gelernt hat, und wem die Erfahrungen des Alleinseins, aber auch die einer Familie und dem damit verbundenen Zusammenhalt fehlen, der verlässt sich später auch nicht auf sich allein. Extreme Erscheinungsformen der Gleichaltrigenorientierung sind nach seiner Meinung tyrannisierendes Verhalten mit Gewaltanwendung, Selbstmorde und Morde unter Kindern und Jugendlichen. Auch die inzwischen allseits bekannten Massenpartys mit Höhepunkten wie Koma-Sauf-Wettbewerbe oder Gang-Bangs, also Massenvergewaltigungen, bei denen die Mädchen vorher zustimmen, können zu diesen Folgen zählen.