One hundred years ago this month – April 1915 – the Allies and Germany were stalemated on the Western Front. Winston Churchill, the young, ambitious First Lord of the British Admiralty proposed a scheme first advanced by France’s prime minister, Aristide Briand.

The best way for Britain and France to end the stalemate and link up to their isolated ally, Russia, would be a daring “coup de main,” or surprise attack, to seize the Ottoman Empire’s Dardanelles, occupy Constantinople (today Istanbul) and knock Turkey out of the First World War. Though rickety, the Ottoman Empire was Germany’s most important wartime ally.

Churchill’s plan was to send battleships of the British and French navies to smash their way through Turkey’ decrepit, obsolete forts along the narrow Dardanelles that connects the Aegean and Mediterranean with the Sea of Marmara, Constantinople and the Black Sea, Russia’s maritime lifeline.

This bold naval intrusion, that some predicted would rival Admiral Horatio Nelson’s dramatic attack in 1801 on Danish-Norwegian Fleet sheltered at Copenhagen, would quickly win the war and achieve for Churchill his ardent ambition of becoming supreme warlord.

Once the Dardanelles was run, 480,000 Allied troops from Britain, France, Australia and New Zealand would land at Gallipoli and other beaches, march north and keep the strategic strait open.

The Dardanelles are relatively narrow, some 1.6 km, a mere rife shot from the European to Asiatic side. In 1810 the British romantic poet Byron swam the Dardanelles to emulate the feat of the ancient Greek hero, Leander.

Churchill convinced his reluctant cabinet colleagues to adopt the bold plan. They should have been more cautious: the French-originated plan was unsound, and the French do not have a happy history in naval affairs.

Efforts by 18 older British and French battleships to force the strait failed miserably. Krupp cannon in the old brick Turkish forts and newly laid mines sank three Allied battleships and badly damaged three others.

The much-heralded French battleship “Bouvet” hit a mine and capsized taking 600 crewmen to their deaths.

Two British and two French battleships were put out of action. This was the last significant French naval action in the Mediterranean until World War II when the British sank the rest of its fleet at Toulon.

Meanwhile, a vast amphibious operation was underway, landing tens of thousands of Allied troops on the Gallipoli Peninsula, mostly on the Aegean side. The landing at Sulva Bay was particularly bloody: the Allied troops were caught in a withering enfilade by Turkish machine guns that turned the sea red.

Churchill’s Gallipoli expedition was a triumph of amphibious daring, a precursor to the Pacific island campaign of World War II. But it was also a planning and logistical disaster in which tens of thousands of brave soldiers were sacrificed for the glory of the politicians.

Churchill at least had seen war fighting the Dervishes up the Nile in Sudan (see his “River War”). So too his dashing colleague Lord Kitchner. Fighting natives armed with spears and swords was one thing.

Fighting Germans and Turks quite another. When Britain’s Imperial Army met the Germans on the Western Front it was savaged. The same is likely to happen if and when the US imperial army, also used to fighting natives, has to face Russian or Chinese regulars.

Churchill and his entourage had failed to properly understand Gallipoli’s torturous topography. What looked easy on maps (many of them incorrect) turned out to be deep gulches, and steep, waterless slopes that proved a nightmare for infantry. Just walking up and down them left me exhausted and winded.

With the racism typical of Imperial Britain, Churchill and the government in London dismissed Turks as backwards, cowardly Muslims. Gallipoli taught them the very opposite.

Out of this fierce battle emerged its hero, Col. Mustafa Kemal Ataturk who defeated the Allies, founded the Turkish republic eight years later, and saved his nation from invasions by Greece, Russia, Italy, Russia and France.

By December, 1915, the Allies began evacuating their troops, a humiliating and bloody defeat at the hands of the “backwards” Turks and their German advisers. The supposed “knockout” blow to the Ottoman Empire ended up knocking out Winston Churchill who was demoted but remained in cabinet for a while. His boss Prime Minister Asquith resigned.

Churchill was at least man enough to take up command of a Scots infantry unit on the Western Front, unlike so many other politicians who sent men to their deaths from the safety of their private clubs in Whitehall.

It is often said that modern Australia and New Zealand were really born as independent nations at Gallipoli, just as the same is said of Canada at the battle of Vimy.

True to a degree, but we should also remember that the British Empire often used its “white troops” from Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Canada as cannon fodder to spare British regiments from the home islands.

The Gallipoli disaster and the surrender of a British army at Kut in Mesopotamia undermined the power and invincibility of the British Empire. The usual patriotic guff aside, 250,000 Allied troops died or were wounded for no good purpose. A similar number of Turkish troops died, but the Turks could at least claim victory and the defense of their nation.

The Australian and New Zealand troops (ANZAC) who had not previously seen combat fought with honor and gallantry. But their commanders and Churchill made one grave blunder after another, recalling the devastating description of the British forces in the 1854 Crimean War, “an army of lions, led by asses.”

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

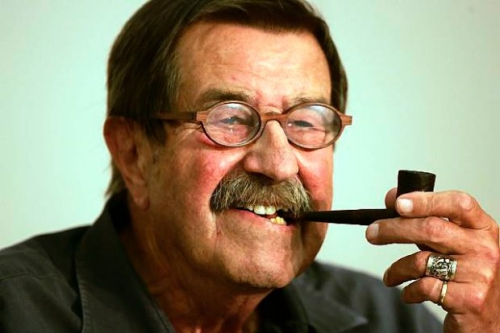

Bij me thuis hangt een litho van Günter Grass met een zelfportret als Dummer August, een domme nar of triestige ‘rode’ clown met een zotskap gemaakt van het krantenpapier waarop de Duitse ‘weldenkende’ pers hem als nazi had besmeurd. Gij domme august, zegt het gedicht dat rond zijn kop gekrabbeld staat, komisch toch zoals ge hier nu muilen staat te trekken onder het snelrecht van de rechtvaardigen: Schnellgericht der Gerechten. Had beter kunnen weten.

Bij me thuis hangt een litho van Günter Grass met een zelfportret als Dummer August, een domme nar of triestige ‘rode’ clown met een zotskap gemaakt van het krantenpapier waarop de Duitse ‘weldenkende’ pers hem als nazi had besmeurd. Gij domme august, zegt het gedicht dat rond zijn kop gekrabbeld staat, komisch toch zoals ge hier nu muilen staat te trekken onder het snelrecht van de rechtvaardigen: Schnellgericht der Gerechten. Had beter kunnen weten. Grass was wel wat tegenstand gewoon, en als meester-spelmaker van de publieke opinie kon hij zijn belagers ook gemakkelijk uiteenspelen. Memorabel is die kaft van Der Spiegel waarop de gevreesde criticus Marcel Reich-Ranicki een roman van Grass letterlijk in tweeën scheurt – hopelijk was het boekwerk al een beetje ‘voorgescheurd’ want in een twee drie kon je de turven van Grass niet zomaar kleinkrijgen: De bot, De rattin, Een gebied zonder eind, De blikken trommel – ik vermeld enkel de ‘dikste’. En telkens won Günter Grass. De bitterheid in de correcte pers werd er niet minder om. Tot ze hem tot prulschrijver degradeerden – precies zoals ze nu doen met de filosoof Peter Sloterdijk.

Grass was wel wat tegenstand gewoon, en als meester-spelmaker van de publieke opinie kon hij zijn belagers ook gemakkelijk uiteenspelen. Memorabel is die kaft van Der Spiegel waarop de gevreesde criticus Marcel Reich-Ranicki een roman van Grass letterlijk in tweeën scheurt – hopelijk was het boekwerk al een beetje ‘voorgescheurd’ want in een twee drie kon je de turven van Grass niet zomaar kleinkrijgen: De bot, De rattin, Een gebied zonder eind, De blikken trommel – ik vermeld enkel de ‘dikste’. En telkens won Günter Grass. De bitterheid in de correcte pers werd er niet minder om. Tot ze hem tot prulschrijver degradeerden – precies zoals ze nu doen met de filosoof Peter Sloterdijk. En dan, natuurlijk, zijn ‘echte’, grote, originele, onnavolgbare debuut: De blikken trommel. Die Blechtrommel is evident een oorlogsroman. Het is juist dat de immer klein blijvende Oskar Matzerath op den duur als ‘pseudo-dwerg’ bij een variétégroep belandt die de soldaten aan het front en aan de Atlantikwall wat amusement moest brengen. Maar de beschreven gebeurtenissen en oorlogshandelingen kunnen niet verder staan van wat bijvoorbeeld een Jonathan Littell evoceert in De welwillenden. Daarin komen slechts gruwelen voor, begeleid door de analyse van de psyche van hen die de gruwelen beramen. Met De blikken trommel konden de Duitsers leven: geschreven van binnenuit, en dus met als stof datgene wat de mensen toentertijd redelijkerwijze konden weten – mensen die immers over geen ooievaarsblik beschikken maar slechts over de beperkte blik van de spelers op de kleine rechthoek waar ze handelen. In vergelijking met wat Reemtsma’s Wehrmacht-tentoonstellingen te zien gaven gebeurt er in De blikken trommel niets. Precies daardoor heeft deze roman bijgedragen tot Auseinandersetzung en Vergangenheitsbewältigung.

En dan, natuurlijk, zijn ‘echte’, grote, originele, onnavolgbare debuut: De blikken trommel. Die Blechtrommel is evident een oorlogsroman. Het is juist dat de immer klein blijvende Oskar Matzerath op den duur als ‘pseudo-dwerg’ bij een variétégroep belandt die de soldaten aan het front en aan de Atlantikwall wat amusement moest brengen. Maar de beschreven gebeurtenissen en oorlogshandelingen kunnen niet verder staan van wat bijvoorbeeld een Jonathan Littell evoceert in De welwillenden. Daarin komen slechts gruwelen voor, begeleid door de analyse van de psyche van hen die de gruwelen beramen. Met De blikken trommel konden de Duitsers leven: geschreven van binnenuit, en dus met als stof datgene wat de mensen toentertijd redelijkerwijze konden weten – mensen die immers over geen ooievaarsblik beschikken maar slechts over de beperkte blik van de spelers op de kleine rechthoek waar ze handelen. In vergelijking met wat Reemtsma’s Wehrmacht-tentoonstellingen te zien gaven gebeurt er in De blikken trommel niets. Precies daardoor heeft deze roman bijgedragen tot Auseinandersetzung en Vergangenheitsbewältigung.

On n’en finit pas de revivre les « années de plomb » en Italie. Là-bas, entre 1968 et 1975, au lieu de mastiquer des marguerites comme tout le monde, jeunes fascistes et jeunes gauchistes se sont livrés à une guerre acharnée. Rien à voir avec les révolutionnaires parisiens de l’époque dont le bla-bla sentencieux endormait jusqu’aux fleurs. Chez nous, on jouait à la révolution. Chez eux, c’était la guerre. De Lotta nazionale, jusqu’aux Brigades rouges, on avalait chaque matin du chien-loup en brochette sur des barbelés. Les vieux de chaque bord étaient maudits. La nostalgie geignarde du passé impérial, des Chemises noires et du salut romain exaspéraient les jeunes fascistes qui vouaient, en revanche, un culte à Mussolini. Même chose en face : les dinosaures du Parti communiste étaient maudits, tandis que Staline, Lénine ou Mao, les vrais monstres, restaient d’indéboulonnables idoles.

On n’en finit pas de revivre les « années de plomb » en Italie. Là-bas, entre 1968 et 1975, au lieu de mastiquer des marguerites comme tout le monde, jeunes fascistes et jeunes gauchistes se sont livrés à une guerre acharnée. Rien à voir avec les révolutionnaires parisiens de l’époque dont le bla-bla sentencieux endormait jusqu’aux fleurs. Chez nous, on jouait à la révolution. Chez eux, c’était la guerre. De Lotta nazionale, jusqu’aux Brigades rouges, on avalait chaque matin du chien-loup en brochette sur des barbelés. Les vieux de chaque bord étaient maudits. La nostalgie geignarde du passé impérial, des Chemises noires et du salut romain exaspéraient les jeunes fascistes qui vouaient, en revanche, un culte à Mussolini. Même chose en face : les dinosaures du Parti communiste étaient maudits, tandis que Staline, Lénine ou Mao, les vrais monstres, restaient d’indéboulonnables idoles.