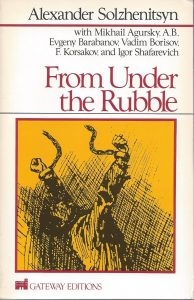

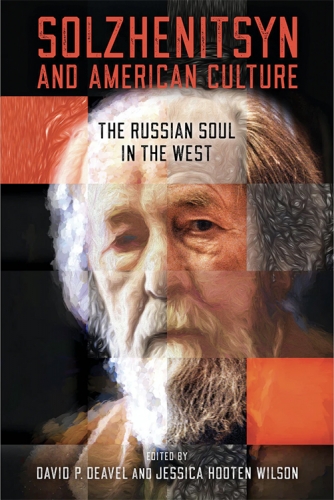

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn et al.

From Under the Rubble

Boston: Little, Brown & Company (1975)

Shortly before being deported from the Soviet Union in 1974, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn contributed three essays to a volume that was later published in the West as From Under the Rubble. The title was a clear metaphor for dissident voices speaking out from beneath the rubble left by communism. The rubble itself represents the remains of the traditional and spiritual life of Solzhenitsyn’s Russia which had been destroyed by the October Revolution and its bloody aftermath. In this volume, Solzhenitsyn lays out what it means to be a nationalist and a dissident against the totalitarian Left. Remarkably little has changed.

Shortly before being deported from the Soviet Union in 1974, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn contributed three essays to a volume that was later published in the West as From Under the Rubble. The title was a clear metaphor for dissident voices speaking out from beneath the rubble left by communism. The rubble itself represents the remains of the traditional and spiritual life of Solzhenitsyn’s Russia which had been destroyed by the October Revolution and its bloody aftermath. In this volume, Solzhenitsyn lays out what it means to be a nationalist and a dissident against the totalitarian Left. Remarkably little has changed.

Today’s Dissident Right will find a mirror image of its struggles in these essays — only needing to make a trivial adjustment of application. One would only need to exchange Solzhenitsyn’s references to Russia or Russians for today’s whites to find a near-perfect fit. Aside from the usual clarity, insight, and depth found in Solzhenitsyn’s work, it’s this familiarity which perhaps gives us the most comfort and inspiration when reading him. We think we have it bad today — Solzhenitsyn had it worse, and he persevered. And if he could persevere, so can we.

* * *

“As Breathing and Consciousness Return,” the first essay in the collection, begins by addressing Solzhenitsyn’s differences with fellow dissident Andrei Sakharov. It’s an illuminating contrast. Although both publicly opposed the repressive Soviets, it was Sakharov who ultimately championed the humanism and individualism of the West which so revolted Solzhenitsyn. Despite being abused and repressed by communism, Sakharov could not bring himself to condemn its socialist underpinnings. In this sense, Sakharov had much in common with the modern liberal. In a famous essay — to which Solzhenitsyn responded in this one — Sakharov had condemned “extremist ideologies” such as fascism, racism, and, most disingenuously, Stalinism. But Solzhenitsyn saw through this prestidigitation as simply a way to deflect blame away from Lenin and the other, supposedly purer, communists of the revolutionary period.

In response, Solzhenitsyn denies that Stalinism even existed. He points to the fact that there is no written Stalinist doctrine, not that Stalin himself had the intellectual horsepower to develop one. He then itemizes all the atrocities committed by Lenin and his cohorts that had little to do with Stalin (“What of the concentration camps (1918-1921)? The summary executions by the Cheka? The savage destruction and plundering of the Church (1922)? The bestial cruelties at Solovki (1922)? None of this was Stalin. . .”) He notes that Stalin’s main departure from Lenin was to inflict the same ruthless repression against his own party, as he did during the Great Terror of the mid-1930s. It’s almost as if Sakharov, who waxed about the “high moral ideals of socialism,” would approve of communism if only it did not devour its own.

Solzhenitsyn uncovers not only the moral shabbiness of liberalism, but the pie-in-the-sky ignorance which fuels it. Basically, we have intellectuals like Sakharov, who were not laborers, trying to convince their readers that “only socialism has raised labor to the peak of moral heroism.” Solzhenitsyn’s response is typically trenchant:

But in the great expanse of our collectivized countryside, where people always and only lived by labor and had no other interest in life but labor, it is only under “socialism” that labor has become an accursed burden from which men flee.

In peering beyond the strife of his age, Solzhenitsyn then distills Sakharov’s enlightened humanism down to what matters most to today’s dissidents: globalist anti-nationalism. It’s the inheritors of Andrei Sakharov who are dogging white ethnonationalists today, and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn saw this in clear relief as far back as 1974. Note the striking similarity between his assertion of nationalism and Greg Johnson’s, from chapter seven of Johnson’s White Nationalist Manifesto:

Solzhenitsyn:

Ah, but what a tough nut it has proved for the millstones of internationalism to crack. In spite of Marxism, the twentieth century has revealed to us the inexhaustible strength and vitality of national feelings and impels us to think more deeply about this riddle: why is the nation a no less sharply defined and irreducible human entity than the individual? Does not national variety enrich mankind as faceting increases the value of a jewel?

Johnson:

The ethnonationalist vision is of a Europe — and a worldwide European diaspora — of a hundred flags, in which every self-conscious nation has at least one sovereign homeland, each of which will strive for the highest degree of homogeneity, allowing the greatest diversity of cultures, languages, dialects, and institutions to flourish.

Solzhenitsyn also points out the double standard of progressives such as Sakharov who aim for greater freedom through greater state control. As a victim of state control himself, Solzhenitsyn argues that this can only lead to “hell on earth.” Sakharov wishes for the state to administer not only scientific and technological progress, but the psychological progress of its citizens as well. Solzhenitsyn finds this questionable, since such “moral exhortations” would be futile without coercive force.

And what would this freedom achieve for us anyway? Like many modern dissidents, Solzhenitsyn doesn’t disparage freedom, but realizes the danger when you have too much of it. Of course, being a devout Christian, he insists that freedom must serve a higher purpose. He pines for Tsarist autocracy in which autocrats were subservient to God. In such systems, the people are indeed freer. When leaders recognize no higher power, the likely outcome becomes totalitarianism, with nothing inhibiting governments from gross atrocity. Even in the so-called liberal democracies in the West, the corruption that must necessarily be birthed by two-party or parliamentary systems crushes the freedoms of the people:

Every party known to history has always defended the interests of this one part against — whom? Against the rest of the people. And in the struggle with other parties it disregards justice for its own advantage: the leader of the opposition . . . will never praise the government for any good it does — that would undermine the interests of the opposition; and the prime minister will never publicly and honestly admit his mistakes — that would undermine the position of the ruling party. If in an electoral campaign dishonest methods can be used secretly — why would they not be? And every party, to a greater or less degree, levels and crushes its members. As a result of all this a society in which political parties are active never rises in the moral scale. In the world today, we doubtfully advance toward a dimly glimpsed goal: can we not, we wonder, rise above the two-party or multiparty parliamentary system? Are there no extraparty or strictly nonparty paths of national development?

What Solzhenitsyn maintains — and what many dissidents today understand — is that land trumps political freedom. People and peoples require land for true freedom. With land they own, people have obligations, self-worth, stability, and a chance at prosperity. And this leads to the most important freedom of all: freedom to think, the freedom to call a lie a lie — lies which require the surrender of our souls to swallow and then repeat. While land ownership helps preserve the physical health of a nation, this inner freedom to resist lies helps preserve its moral health.

Referring to the pre-moderns. . .

[T]hey preserved the physical health of the nation (obviously they did, since the nation did not die out). They preserved its moral health, too, which has left its imprint at least on folklore and proverbs — a level of moral health incomparably higher than that expressed today in simian radio music, pop songs, and insulting advertisements: could a listener from outer space imagine that our planet had already known and left behind it Bach, Rembrandt, and Dante?

Solzhenitsyn’s connection to today’s Dissident Right can be seen in how he places an almost mystical imperative upon the nation and one’s obligation to it through work and honest living. Human beings are weak, and when tempted with freedom, they will often give in to corruption or corrupt others. This can lead to either the decay of society (as Solzhenitsyn witnessed in the West) or its demise through totalitarianism (as he so famously experienced in the Soviet Union). Both outcomes threaten the health and future of nations. Andrei Sakharov recognized the danger of the latter, but not the former — indeed it was his globalist progressivism that has led the West even further into decadence and corruption in the years since From Under the Rubble was published.

To speak out against this makes one a dissident. Solzhenitsyn was not only a dissident against totalitarianism, he was also a dissident against Western decadence, the same Western decadence that has led to non-white immigration and the ongoing destruction of the civilizations that white people created millennia ago. Beneath this is the lie of racial egalitarianism, and modern whites are being fed this lie in nearly the same manner as which the Soviet people were fed the lie of class egalitarianism.

Solzhenitsyn teaches us to never give in to this lie.

And no one who voluntarily runs with the hounds of falsehood, or props it up, will ever be able to justify himself to the living, or to posterity, or to his friends, or to his children.

* * *

“Repentance and Self-Limitation in the Life of Nations” bears a much more obvious and direct connection to modern white dissidents than the previous essay. In it, Solzhenitsyn exhorts his fellow Russians to seek absolution and redemption for the sins of the Russian past. He is quite sincere about this, and believes that, to an extent, his people cannot move forward in friendship with other peoples (or with themselves) without contrite acknowledgment of past atrocities. “Repentance is the only starting point for spiritual growth,” he tells us. Since, as we discussed above, Solzhenitsyn believed in the distinct character of individual nations, he also believed that nations “. . . are very vital formations, susceptible to all moral feelings, including — however painful a step it may be — repentance.”

So far, so bad, today’s dissident might tell us. Is this not how whites are expected to behave in the face of endless waves of non-white immigration into their homelands? Such people, as well as blacks and Jews in the United States, demand repentance for colonialism, imperialism, slavery, the Jewish Holocaust, the list goes on. Aren’t these demands the weapons non-whites use against whites to usurp their very civilization?

Certainly, they are. Solzhenitsyn understood the abusive and one-sided nature of this relationship and concludes his essay with two points that redeem it entirely. One, that Russians have no obligations to repent unless those nations attempting to extract repentance also repent. For example, Solzhenitsyn readily accepts Russia’s guilt for past behavior, some of which he witnessed personally during World War II:

. . . but we all remember, and there will yet be occasion to say it out loud: the noble stab in the back for dying Poland on 17 September 1939; the destruction of the flower of the Polish people in our camps, Katyn in particular; and our gloating, heartless immobility on the bank of the Vistula in August 1944, whence we gazed through our binoculars at Hitler crushing the rising of the nationalist forces in Warsaw — no need for them to get big ideas, we will find the right people to put in the government. (I was nearby, and I speak with certainty: the impetus of our advance was such that the forcing of the Vistula would have been no problem, and it would have changed the fate of Warsaw.)

After this, however, he then offers up a prodigious list of atrocities that the Poles themselves committed in the past and explains that the Polish lack of repentance for them (both historical and contemporary) makes it difficult for him to unburden his heart to them.

Well then, has any wave of regret rolled over educated Polish society, any wave of repentance surged through Polish literature? Never. Even the Arians, who were opposed to war in general, had nothing special to say about the subjugation of the Ukraine and Byelorussia. During our Time of Troubles, the eastward expansion of Poland was accepted by Polish society as a normal and even praiseworthy policy. The Poles thought themselves as God’s chosen people, the bastion of Christianity, whose mission was to carry true Christianity to the “semipagan” Orthodox of savage Muscovy, and to be the propagators of Renaissance university culture.

In the face of this, Solzhenitsyn expects nothing less than “mutual repentance” for his ideas to become applicable. This is exactly the attitude white people should take in the face of non-whites living in their homelands. If American blacks demand whites repent over slavery, then they themselves must repent over the horrific surge of crime, corruption, rape, and murder that they have presided over since the abolition of slavery. If Jews demand whites to repent over the Jewish Holocaust then they themselves must repent over their leading role in the October Revolution, the Holodomor, the Great Terror, and the Gulag Archipelago, all of which resulted in tens of millions killed. All groups of people have atrocities in their past which were committed both against themselves and others (and, in many cases, against white people).

So if non-whites wish to make white people repent for the past, whites should follow Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s lead by saying two words:

“You first.”

Second, Solzhenitsyn underscores Russian suffering in the past. If a nation has been both victimizer and victim throughout history, then abject mea culpas simply become inappropriate. Solzhenitsyn understood historical Russian suffering well (and experienced its contemporary suffering firsthand as a Gulag zek in the 1940s and 1950s). There is no pulling the wool over his eyes. Quotes such as these say it all:

The memory of the Tartar yoke in Russia must always dull our possible sense of guilt toward the remnant of the Golden Horde.

And

Did not the revolution throughout its early years have some of the characteristics of a foreign invasion? When in a foraging party, or the punitive detachment which came down to destroy a rural district, there would be Finns, there would be Austrians, but hardly anyone who spoke Russian? When the organs of the Cheka teemed with Latvians, Poles, Jews, Hungarians, Chinese?

It may seem weak or effeminate for whites to play the victim card, but as the non-whites have shown, it is a powerful card. All whites must play it in order to counter it when played against them. As discussed above, tens of millions of whites were murdered, starved to death, or incarcerated by the Soviet system between the world wars. Whites must follow Solzhenitsyn’s logic and own this. For example, when American blacks demand repentance over slavery, whites need to point out that whites were brought to North America as slaves in similar numbers, under equally hazardous circumstances, and were in many cases treated worse than the blacks were. And if blacks wish to complain about contemporary racism or segregation, whites must counter with crime statistics and the undeniable fact that blacks victimize whites in these crimes many more times than the reverse.

Fortunately, Solzhenitsyn sees beyond all this and wants the endless finger-pointing to end.

Who has no guilt? We are all guilty. But at some point the endless account must be closed, we must stop discussing whose crimes are more recent, more serious and affect most victims. It is useless for even the closest neighbors to compare the duration and gravity of their grievances against each other. But feelings of penitence can be compared.

And compare we must. This is may not change the minds of the enemies of whites, but it will stiffen the resolve of white people. And what do a people need more than resolve in order to survive and thrive?

* * *

In “The Smatterers,” Solzhenitsyn’s final contribution to From Under the Rubble, our author outlines the defining characteristics of the Soviet intelligentsia to the point of creating a universal type. Thanks to Solzhenitsyn’s ruthless insight into human nature, all dissidents on the Right now have a reliable blueprint for their Left-wing, humanist oppressors. Several decades and thousands of miles may separate many of us from Solzhenitsyn’s Soviet dystopia, but in “The Smatterers,” one of his most prescient works, Solzhenitsyn shows us that his enemies are indeed our enemies. Nothing fundamental has changed with the Left. Its adherents today follow the same psychological pattern and ape the same grotesque behaviors of the Soviet and pre-Soviet elite which beleaguered dissidents throughout the twentieth century.

Some of these characteristics are itemized below:

Anti-Racism: “Love of egalitarian justice, the social good and the material well-being of the people, which paralyzed its love and interest in the truth. . .”

Passionate Intolerance: “Infatuation with the intelligentsia’s general credo; ideological intolerance; hatred as a passionate ethical impulse.”

Atheism: “A strenuous, unanimous atheism which uncritically accepted the competence of science to decide even matters of religion — once and for all and of course negatively; dogmatic idolatry of man and mankind; the replacement of religion by a faith in scientific progress.”

Anti-Nationalism: “Lack of sympathetic interest in the history of our homeland, no feeling of blood relationship with its history.”

Hypocrisy: “Perfectly well aware of the shabbiness and flabbiness of the party lie and ridiculing among themselves, they yet cynically repeat the lie with their very next breath, issuing ‘wrathful’ protests and newspaper articles in ringing, rhetorical tones. . .”

Materialism: “. . . it is disgusting to see all ideas and convictions subordinated to the mercenary pursuit of bigger and better salaries, titles, positions, apartments, villas, cars. . .”

Ideological Submission: “For all this, people are not ashamed to toe the line punctiliously, break off all unapproved friendships, carry out all the wishes of their superiors and condemn any of their colleagues either in writing or from a public platform, or simply by refusing to shake his hand, if the party committee orders them to.”

Arrogance: “An overweening insistence on the opposition between themselves and the “philistines.” Spiritual arrogance. The religion of self-deification — the intelligentsia sees its existence as providential for the country.” (Solzhenitsyn also points out how the Soviet intelligentsia of his day would give their dogs peasant names, such as Foma, Kuzma, Potap, Makar, and Timofei.)

With his typical wry sense of humor, Solzhenitsyn asks, “If all these are the qualities of the intelligentsia, who are the philistines?”

Seriously, however, could anyone have turned in a more accurate depiction of today’s Leftist avengers who use government and big tech corporations as weapons against the people? Yes, some of the above characteristics are shared by all decadent elites. And yes, today’s milieu has become far more degenerate than Solzhenitsyn’s (racial diversity, non-white immigration, feminism, gay rights, and transgenderism will do that). But the source of power behind both elites remains the same: “the maintenance of the obligatory ideological lie.”

As discussed above, in Solzhenitsyn’s day, the lie was class egalitarianism; today it is racial and gender egalitarianism. One must enthusiastically support and propagate such lies to become part of the country’s elite. There is no second path. In fact, for these elites, these smatterers, as Solzhenitsyn calls them, following any second path becomes anathema and must be swiftly punished. He draws a straight line from the “atheistic humanism” of the smatterers to the “hastily constituted revolutionary tribunals and the rough justice meted out in the cellars of the Cheka.”

This is how nations lose their souls. Forcing lies onto a nation’s elite warps them — it makes their minds inconsequential but their actions highly consequential.

Then millions of cottages — as well-designed and comfortable as one could wish — were completely ravaged, pulled down or put into the wrong hands and five million hardworking, healthy families, together with infants still at the breast, were dispatched to their death on long winter journeys or on their arrival in the tundra. (And our intelligentsia did not waver or cry out, and its progressive part even assisted in driving them out. That was when the intelligentsia ceased to be, in 1930. . .)

And not just in the Soviet Union. Smatterers in the West are equally consequential. Back in the early 1970s, Solzhenitsyn predicted the immigration crisis which is now ravaging Europe, and correctly blamed it on the “spirit of internationalism and cosmopolitanism” of these smatterers. The following passage is uncannily prescient:

In Great Britain, which still clings to the illusion of a mythical British Commonwealth and where society is keenly indignant over the slightest racial discrimination, it has led to the country’s being inundated with Asians and West Indians who are totally indifferent to the English land, its culture and traditions, and are simply seeking to latch onto a ready-made high standard of living. Is this such a good thing?

Solzhenitsyn’s answer to all of this, and the action he prescribes, is to simply reject the lie. This, to him, is more important than “our salaries, our families, and our leisure.” Even our very lives. This is what makes a dissident a dissident. Many in his day and ours justify accepting the ideological lie for the sake of their children. Solzhenitsyn responds by asking what kind of degenerate society will we bequeath to our children and grandchildren if we don’t stand up to these lies? Because Solzhenitsyn bears a blood identification with the Russian nation (as the Dissident Right today does with the white European diaspora), he believes that no personal gain or loss can outweigh the importance of rejecting ideological lies. This, as much as anything, preserves the spiritual and ultimately the physical health of a nation and a people.

If you want to support Counter-Currents, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [4] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every weekend on DLive [5].

Don’t forget to sign up [6] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg