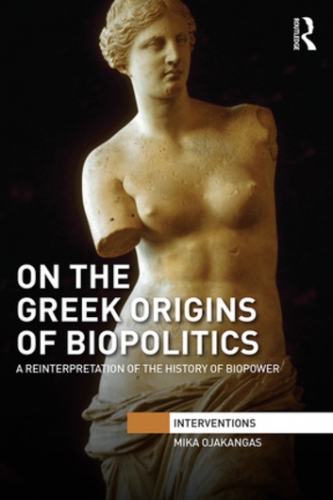

Mika Ojakangas is a professor of political theory, teaching at the University of Jyväskylä in Finland. He has written a succinct and fairly comprehensive overview of ancient Greek thought on population policies and eugenics, or what he terms “biopolitics.” Ojakangas says:

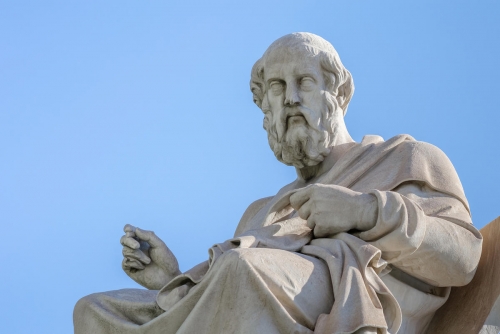

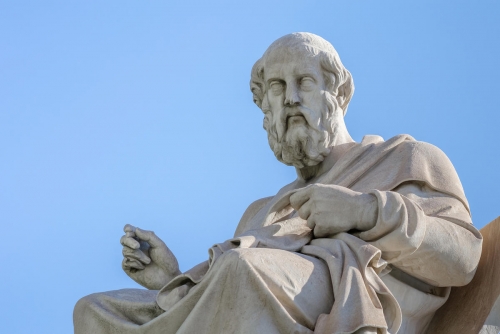

In their books on politics, Plato and Aristotle do not only deal with all the central topics of biopolitics (sexual intercourse, marriage, pregnancy, childbirth, childcare, public health, education, birthrate, migration, immigration, economy, and so forth) from the political point of view, but for them these topics are the very keystone of politics and the art of government. At issue is not only a politics for which “the idea of governing people” is the leading idea but also a politics for which the question how “to organize life” (tou zên paraskeuên) (Plato, Statesman, 307e) is the most important question. (6)

The idea of regulating and cultivating human life, just as one would animal and plant life, is then not a Darwinian, eugenic, or Nazi modern innovation, but, as I have argued concerning Plato’s Republic, can be found in a highly developed form at the dawn of Western civilization. As Ojakangas says:

The idea of politics as control and regulation of the living in the name of the security, well-being and happiness of the state and its inhabitants is as old as Western political thought itself, originating in classical Greece. Greek political thought, as I will demonstrate in this book, is biopolitical to the bone. (1)

Greek thought had nothing to do with the modern obsessions with supposed “human rights” or “social contracts,” but took the good to mean the flourishing of the community, and of individuals as part of that community, as an actualization of the species’ potential: “In this biopolitical power-knowledge focusing on the living, to repeat, the point of departure is neither law, nor free will, nor a contract, or even a natural law, meaning an immutable moral rule. The point of departure is the natural life (phusis) of individuals and populations” (6). Okajangas notes: “for Plato and Aristotle politics was essentially biopolitics” (141).

In Ojakangas’ telling, Western biopolitical thought gradually declined in the ancient and medieval period. Whereas Aristotle and perhaps Plato had thought of natural law and the good as pertaining to a particular organism, the Stoics, Christians, and liberals posited a kind of a disembodied natural law:

This history is marked by several ruptures understood as obstacles preventing the adoption and diffusion of the Platonic-Aristotelian biopolitical model of politics – despite the influence these philosophers have otherwise had on Roman and Christian thought. Among these ruptures, we may include: the legalization of politics in the Roman Republic and the privatization of everyday life in the Roman Empire, but particularly the end of birth control, hostility towards the body, the sanctification of law, and the emergence of an entirely new kind of attitude to politics and earthly government in early Christianity. (7)

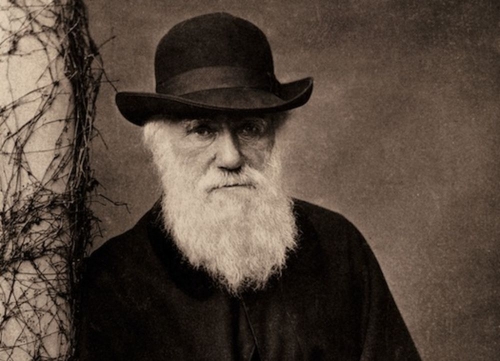

Ojakangas’ book has served to confirm my impression that, from an evolutionary point of view, the most relevant Western thinkers are found among the ancient Greeks, with a long sleep during the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages, a slow revival during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, and a great climax heralded by Darwin, before being shut down again in 1945. The periods in which Western thought was eminently biopolitical — the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. and 1865 to 1945 — are perhaps surprisingly short in the grand scheme of things, having been swept away by pious Europeans’ recurring penchant for egalitarian and cosmopolitan ideologies. Okajangas also admirably puts ancient biopolitics in the wider context of Western thought, citing Spinoza, Nietzsche, Carl Schmitt, Heidegger, and others, as well as recent academic literature.

Ojakangas’ book has served to confirm my impression that, from an evolutionary point of view, the most relevant Western thinkers are found among the ancient Greeks, with a long sleep during the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages, a slow revival during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, and a great climax heralded by Darwin, before being shut down again in 1945. The periods in which Western thought was eminently biopolitical — the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. and 1865 to 1945 — are perhaps surprisingly short in the grand scheme of things, having been swept away by pious Europeans’ recurring penchant for egalitarian and cosmopolitan ideologies. Okajangas also admirably puts ancient biopolitics in the wider context of Western thought, citing Spinoza, Nietzsche, Carl Schmitt, Heidegger, and others, as well as recent academic literature.

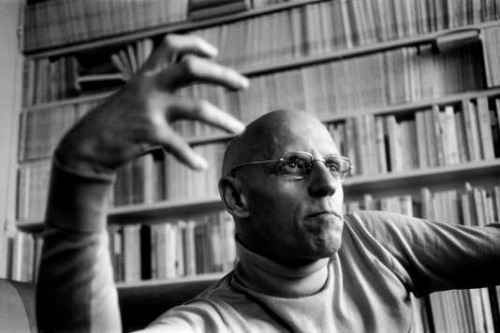

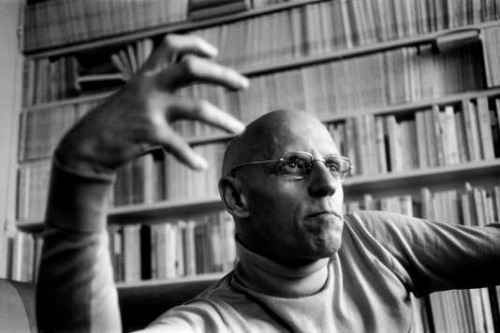

At the core of the work is a critique of Michel Foucault’s claim that biopolitics is a strictly modern phenomenon growing out of “Christian pastoral power.” Ojakangas, while sympathetic to Foucault, says the latter’s argument is “vague” (33) and unsubstantiated. Indeed, historically at least, Catholic countries with strong pastoral power tended precisely to be those in which eugenics was less popular, in contrast with Protestant ones.

It must be said that postmodernist pioneer Foucault is a strange starting point on the topic of biopolitics. As Ojakangas suggests, Foucault’s 1979 and 1980 lecture courses The Birth of Biopolitics and On the Government of the Living do not deal mainly with biopolitics at all, despite their titles (34–35). Indeed, Foucault actually lost rapidly lost interest in the topic.

Okajangas also criticizes Hannah Arendt for claiming that Aristotle posited a separation between the familial/natural life of the household (oikos) and that of the polis. In fact: “The Greek city-state was, to use Carl Schmitt’s infamous formulation, a total state — a state that intervenes, if it so wishes, in all possible matters, in economy and in all the other spheres of human existence” (17). Okajangas goes into some detail citing, contra Arendt and Foucault, ancient Greek uses of household-management and shepherding as analogies for political rule.

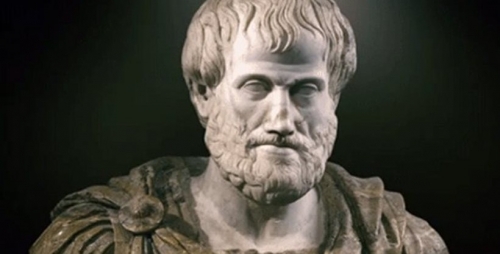

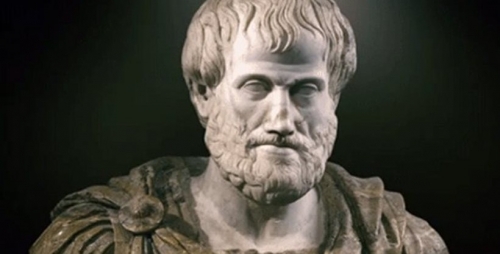

Aristotle appears as a genuine forerunner of modern scientific biopolitics in Ojakangas’ account. Aristotle’s politics was at once highly conventional, really reflecting more widespread Greek assumptions, and his truly groundbreaking work as an empirical scientist, notably in the field of biology. For Aristotle “the aim of politics and state administration is to produce good life by developing the immanent potentialities of natural life and to bring these potentialities to fruition” (17, cf. 107). Ojakangas goes on:

Aristotle was not a legal positivist in the modern sense of the word but rather a representative of sociological naturalism, as for Aristotle there is no fundamental distinction between the natural and the social world: they are both governed by the same principles discovered by empirical research on the nature of things and living beings. (55–56)

And: “although justice is based on nature, at stake in this nature is not an immutable and eternal cosmic nature expressing itself in the law written on the hearts of men and women but nature as it unfolds in a being” (109).

This entailed a notion of justice as synonymous with natural hierarchy. Okajangas notes: “for Plato justice means inequality. Justice takes place when an individual fulfills that function or work (ergon) that is assigned to him by nature in the socio-political hierarchy of the state — and to the extent that everybody does so, the whole city-state is just” (111). Biopolitical justice is when each member of the community is fulfilling the particular role to which he is best suited to enable the species to flourish: “For Plato and Aristotle, in sum, natural justice entails hierarchy, not equality, subordination, not autonomy” (113). Both Plato and Aristotle adhered to a “geometrical” conception of equality between humans, namely, that human beings were not equal, but should be treated in accordance with their worth or merit.

Plato used the concepts of reason and nature not to comfort convention but to make radical proposals for the biological, cultural, and spiritual perfection of humanity. Okajangas rightly calls the Republic a “bio-meritocratic” utopia (19) and notes that “Platonic biopolitico-pastoral power” was highly innovative (134). I was personally also extremely struck in Plato by his unique and emphatic joining together of the biological and the spiritual. Okajangas says that National Socialist racial theoriar Hans F. K. Günther in his Plato as Protector of Life (1928) had argued that “a dualistic reading of Plato goes astray: the soul and the body are not separate entities, let alone enemies, for the spiritual purification in the Platonic state takes place only when accompanied with biological selection” (13).[1]

Okajangas succinctly summarizes the decline of biopolitics in the ancient world. Politically this was related to the decline of the intimate and “total” city-state:

It indeed seems that the decline of the classical city-state also entailed a crisis of biopolitical vision of politics. . . . Just like modern biopolitics, which is closely linked to the rise of the modern nation-state, it is quite likely that the decline of biopolitics and biopolitical vision of politics in the classical era is related to the fall of the ethnically homogeneous political organization characteristic of the classical city-states. (118)

The rise of Hellenistic and Roman empires as universal, cultural states naturally entailed a withdrawal of citizens from politics and a decline in self-conscious ethnopolitics.

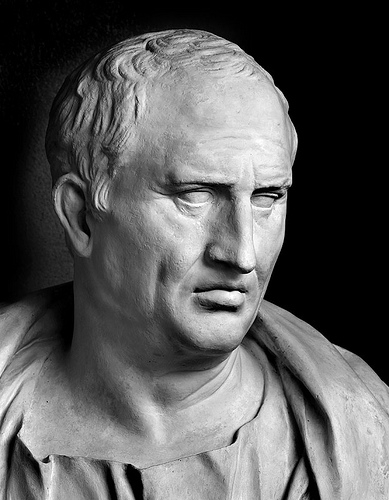

While Rome had also been founded as “a biopolitical regime” and had some policies to promote fertility and eugenics (120), this was far less central to Roman than to Greek thought, and gradually declined with the Empire. Political ideology seems to have followed political realities. The Stoics and Cicero posited a “natural law” not deriving from a particular organism, but as a kind of cosmic, disembodied moral imperative, and tended to emphasize the basic commonality of human beings (e.g. Cicero, Laws, 1.30).

While Rome had also been founded as “a biopolitical regime” and had some policies to promote fertility and eugenics (120), this was far less central to Roman than to Greek thought, and gradually declined with the Empire. Political ideology seems to have followed political realities. The Stoics and Cicero posited a “natural law” not deriving from a particular organism, but as a kind of cosmic, disembodied moral imperative, and tended to emphasize the basic commonality of human beings (e.g. Cicero, Laws, 1.30).

I believe that the apparently unchanging quality of the world and the apparent biological stability of the species led many ancient thinkers to posit an eternal and unchanging disembodied moral law. They did not have our insights on the evolutionary origins of our species and of its potential for upward change in the future. Furthermore, the relative commonality of human beings in the ancient Mediterranean — where the vast majority were Aryan or Semitic Caucasians, with some clinal variation — could lead one to think that biological differences between humans were minor (an impression which Europeans abandoned in the colonial era, when they encountered Sub-Saharan Africans, Amerindians, and East Asians). Missing, in those days before modern science and as White advocate William Pierce has observed, was a progressive vision of human history as an evolutionary process towards ever-greater consciousness and self-actualization.[2]

Many assumptions of late Hellenistic (notably Stoic) philosophy were reflected and sacralized in Christianity, which also posited a universal and timeless moral law deriving from God, rather than the state or the community. As it is said in the Book of Acts (5:29): “We must obey God rather than men.” With Christianity’s emphasis on the dignity of each soul and respect for the will of God, the idea of manipulating reproductive processes through contraception, abortion, or infanticide in order to promote the public good became “taboo” (121). Furthermore: “virginity and celibacy were as a rule regarded as more sacred states than marriage and family life . . . . The dying ascetic replaced the muscular athlete as a role model” (121). These attitudes gradually became reflected in imperial policies:

All the marriage laws of Augustus (including the system of legal rewards for married parents with children and penalties for the unwed and childless) passed from 18 BC onwards were replaced under Constantine and the later Christian emperors — and even those that were not fell into disuse. . . . To this effect, Christian emperors not only made permanent the removal of sanctions on celibates, but began to honor and reward those Christian priests who followed the rule of celibacy: instead of granting privileges to those who contracted a second marriage, Justinian granted privileges to those who did not (125)

The notion of moral imperatives deriving from a disembodied natural law and the equality of souls gradually led to the modern obsession with natural rights, free will, and social contracts. Contrast Plato and Aristotle’s eudaimonic (i.e., focusing on self-actualization) politics of aristocracy and community to that of seventeenth-century philosopher Thomas Hobbes:

I know that in the first book of the Politics Aristotle asserts as a foundation of all political knowledge that some men have been made by nature worthy to rule, others to serve, as if Master and slave were distinguished not by agreement among men, but by natural aptitude, i.e. by their knowledge or ignorance. This basic postulate is not only against reason, but contrary to experience. For hardly anyone is so naturally stupid that he does not think it better to rule himself than to let others rule him. … If then men are equal by nature, we must recognize their equality; if they are unequal, since they will struggle for power, the pursuit of peace requires that they are regarded as equal. And therefore the eighth precept of natural law is: everyone should be considered equal to everyone. Contrary to this law is PRIDE. (De Cive, 3.13)

It does seem that, from an evolutionary point of view, the long era of medieval and early modern thought represents an enormous regression as compared with the Ancients, particularly the Greeks. As Ojakangas puts it: “there is an essential rupture in the history of Western political discourse since the decline of the Greek city-states” (134).

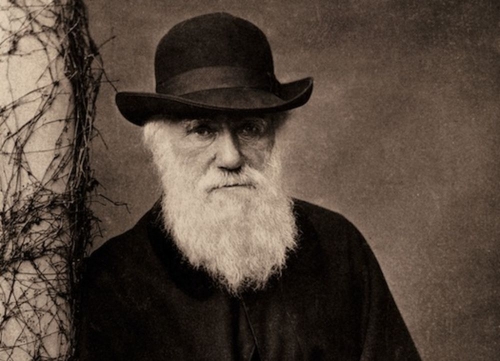

Western biopolitics gradually returned in the modern era and especially with Darwin, who himself had said in The Descent of Man: “The weak members of civilized societies propagate their kind. No one who has attended to the breeding of domestic animals will doubt that this must be highly injurious to the race of man.”[3] And: “Man scans with scrupulous care the character and pedigree of his horses, cattle, and dogs before he matches them; but when he comes to his own marriage he rarely, or never, takes any such care.”[4] Okajangas argues that “the Platonic Aristotelian art of government [was] more biopolitical than the modern one,” as they did not have to compromise with other traditions, namely “Roman and Judeo-Christian concepts and assumptions” (137).

Okajangas’ book is useful in seeing the outline of the long tradition of Western biopolitical thinking, despite the relative eclipse of the Middle Ages. He says:

Baruch Spinoza was probably the first modern metaphysician of biopolitics. While Kant’s moral and political thought is still centered on concepts such as law, free will, duty, and obligation, in Spinoza we encounter an entirely different mode of thinking: there are no other laws but causal ones, the human will is absolutely determined by these laws, freedom and happiness consist of adjusting oneself to them, and what is perhaps most essential, the law of nature is the law of a self-expressing body striving to preserve itself (conatus) by affirming itself, this affirmation, this immanent power of life, being nothing less than justice. In the thought of Friedrich Nietzsche, this metaphysics of biopolitics is brought to its logical conclusion. The law of life is nothing but life’s will to power, but now this power, still identical with justice, is understood as a process in which the sick and the weak are eradicated by the vital forces of life.

I note in passing that William Pierce had a similar assessment of Spinoza’s pantheism as basically valid, despite the latter’s Jewishness.[5]

The 1930s witnessed the zenith of modern Western biopolitical thinking. The French Nobel Prize winner and biologist Alexis Carrel had argued in his best-selling Man the Unknown for the need for eugenics and the need for “philosophical systems and sentimental prejudices must give way before such a necessity.” Yet, as Okajangas points out, “if we take a look at the very root of all ‘philosophical systems,’ we find a philosophy (albeit perhaps not a system) perfectly in agreement with Carrel’s message: the political philosophy of Plato” (97).

Okajangas furthermore argues that Aristotle’s biocentric naturalist ethics were taken up in 1930s Germany:

Instead of ius naturale, at stake was rather what the modern human sciences since the nineteenth century have called biological, economical, and sociological laws of life and society — or what the early twentieth-century völkisch German philosophers, theologians, jurists, and Hellenists called Lebensgesetz, the law of life expressing the unity of spirit and race immanent to life itself. From this perspective, it is not surprising that the “crown jurist” of the Third Reich, Carl Schmitt, attacked the Roman lex [law] in the name of the Greek nomos [custom/law] — whose “original” meaning, although it had started to deteriorate already in the post-Solonian democracy, can in Schmitt’s view still be detected in Aristotle’s Politics. Cicero had translated nomos as lex, but on Schmitt’s account he did not recognize that unlike the Roman lex, nomos does not denote an enacted statute (positive law) but a “concrete order of life” (eine konkrete Lebensordnung) of the Greek polis — not something that ‘ought to be’ but something that “is”. (56)

Western biopolitical thought was devastated by the outcome of the World War II and has yet to recover, although perhaps we can begin to see glimmers of renewal.

Okajangas reserves some critical comments for Foucault in his conclusion, arguing that with his erudition he could not have been ignorant of classical philosophy’s biopolitical character. He speculates on Foucault’s motivations for lying: “Was it a tactical move related to certain political ends? Was it even an attempt to blame Christianity and traditional Christian anti-Semitism for the Holocaust?” (142). I am in no position to pronounce on this, other than to point out that Foucault, apparently a gentile, was a life-long leftist, a Communist Party member in the 1950s, a homosexual who eventually died of AIDS, and a man who — from what I can make of his oeuvre — dedicated his life to “problematizing” the state’s policing and regulation of abnormality.

Okajangas’ work is scrupulously neutral in his presentation of ancient biopolitics. He keeps his cards close to his chest. I identified only two rather telling comments:

- His claim that “we know today that human races do not exist” (11).

- His assertion that “it would be childish to denounce biopolitics as a multi-headed monster to be wiped off the map of politics by every possible means (capitalism without biopolitics would be an unparalleled nightmare)” (143).

The latter’s odd phrasing strikes me as presenting an ostensibly left-wing point to actually make a taboo right-wing point (a technique Slavoj Žižek seems to specialize in).

In any event, I take Ojakangas’ work as a confirmation of the utmost relevance of ancient political philosophy for refounding European civilization on a sound biopolitical basis. The Greek philosophers, I believe, produced the highest biopolitical thought because they could combine the “barbaric” pagan-Aryan values which Greek society took for granted with the logical rigor of Socratic rationalism. The old pagan-Aryan culture, expressed above all in the Homeric poems, extolled the values of kinship, aristocracy, competitiveness, community, and manliness, this having been a culture which was produced by a long, evolutionary struggle for survival among wandering and conquering tribes in the Eurasian steppe. This highly adaptive traditional culture was then, by a uniquely Western contact with rationalist philosophy, rationalized and radicalized by the philosophers, untainted by the sentimentality of later times. Plato and Aristotle are remarkably un-contrived and straightforward in their political methods and goals: the human community must be perfected biologically and culturally; individual and sectoral interests must give way to those of the common good; and these ought to be enforced through pragmatic means, in accord with wisdom, with law where possible, and with ruthlessness when necessary.

[1]Furthermore, on a decidedly spiritual note: “ rather than being a Darwinist of sorts, in Günther’s view it is Plato’s idealism that renders him a predecessor of Nazi ideology, because race is not merely about the body but, as Plato taught, a combination of the mortal body and the immortal soul.” (13)

[2] William Pierce:

The medieval view of the world was that it is a finished creation. Since Darwin, we have come to see the world as undergoing a continuous and unfinished process of creation, of evolution. This evolutionary view of the world is only about 100 years old in terms of being generally accepted. . . . The pantheists, at least most of them, lacked an understanding of the universe as an evolving entity and so their understanding was incomplete. Their static view of the world made it much more difficult for them to arrive at the Cosmotheist truth.

William Pierce, “Cosmotheism: Wave of the Future,” speech delivered in Arlington, Virginia 1977.

[3] Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex (New York: Appleton and Company, 1882), 134.

[4]Ibid., 617. Interestingly, Okajangas points out that Benjamin Isaac, a Jewish scholar writing on Greco-Roman “racism,” believed Plato (Republic 459a-b) had inspired Darwin on this point. Benjamin Isaac, The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2004), 128.

[5]Pierce, “Cosmotheism.”

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Ojakangas’ book has served to confirm my impression that, from an evolutionary point of view, the most relevant Western thinkers are found among the ancient Greeks, with a long sleep during the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages, a slow revival during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, and a great climax heralded by Darwin, before being shut down again in 1945. The periods in which Western thought was eminently biopolitical — the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. and 1865 to 1945 — are perhaps surprisingly short in the grand scheme of things, having been swept away by pious Europeans’ recurring penchant for egalitarian and cosmopolitan ideologies. Okajangas also admirably puts ancient biopolitics in the wider context of Western thought, citing Spinoza, Nietzsche, Carl Schmitt, Heidegger, and others, as well as recent academic literature.

Ojakangas’ book has served to confirm my impression that, from an evolutionary point of view, the most relevant Western thinkers are found among the ancient Greeks, with a long sleep during the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages, a slow revival during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, and a great climax heralded by Darwin, before being shut down again in 1945. The periods in which Western thought was eminently biopolitical — the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. and 1865 to 1945 — are perhaps surprisingly short in the grand scheme of things, having been swept away by pious Europeans’ recurring penchant for egalitarian and cosmopolitan ideologies. Okajangas also admirably puts ancient biopolitics in the wider context of Western thought, citing Spinoza, Nietzsche, Carl Schmitt, Heidegger, and others, as well as recent academic literature.

While Rome had also been founded as “a biopolitical regime” and had some policies to promote fertility and eugenics (120), this was far less central to Roman than to Greek thought, and gradually declined with the Empire. Political ideology seems to have followed political realities. The Stoics and Cicero posited a “natural law” not deriving from a particular organism, but as a kind of cosmic, disembodied moral imperative, and tended to emphasize the basic commonality of human beings (e.g. Cicero, Laws, 1.30).

While Rome had also been founded as “a biopolitical regime” and had some policies to promote fertility and eugenics (120), this was far less central to Roman than to Greek thought, and gradually declined with the Empire. Political ideology seems to have followed political realities. The Stoics and Cicero posited a “natural law” not deriving from a particular organism, but as a kind of cosmic, disembodied moral imperative, and tended to emphasize the basic commonality of human beings (e.g. Cicero, Laws, 1.30).