Carl Schmitt y el Federalismo

Por Luís María Bandieri*

Ex: http://www.disenso.org/

Cuando se trata de abordar la relación que el título de este trabajo propone, entre nuestro autor y el concepto jurídico-político de federación, aparece de inmediato una dificultad. El federalismo resulta un tema episódico en su obra -un índice temático de la opera omnia schmittiana registraría escasas entradas del término. Más aún, puede sospecharse que se trata, antes que de una presencia restringida y a contraluz, de una ausencia a designio. Entonces, además de reseñar lo que dice sobre el federalismo, cabría preguntarse, también, el por qué de lo que calla. Schmitt es un autor tan vasto y profundo que, como todos los de su categoría, habla también por sus silencios, dejando una suerte de "escritura invisible" que el investigador no puede desdeñar.

El lector de Schmitt advierte, ante todo, que cuando nuestro autor se refiere al Estado, a la "unidad política" por excelencia, no suele detallar las modalidades de su organización interna y, especialmente, de cómo se articula hacia adentro, funcional o territorialmente, el poder. Autodefinido como último representante del jus publicum europaeum, Schmitt destaca en el Estado su capacidad de lograr la paz interior, sin preguntarse demasiado por cuáles mecanismos se alcanza. Las preguntas iniciales, pues, podrían ser: formuladas así: ¿cabe el federalismo dentro de la estatalidad clásica, propia de aquel jus publicum y tan cara a Schmitt? ¿Nuestro autor concibió otras formas políticas trascendentes a aquella estatalidad clásica? Si ese ir más allá se dio ¿hubo lugar para el federalismo?

En principio, aunque luego se verá que esta caracterización resulta insuficiente, cuando nos referimos al federalismo, según surge de la literatura jurídica corriente en nuestro país, nos referimos a una forma particular de articulación territorial del poder. El control de un territorio por el aparato de poder del Estado.

El control de un territorio por parte del Estado puede realizarse fundamentalmente de dos maneras:

El primero es un modelo unitario o centralista. El segundo es el modelo federal o más exactamente “federativo”. La Argentina, por ejempo, es un Estado federativo compuesto por estados provinciales federados. La confederación resulta un procedimiento de articulación territorial del poder donde un cierto número de Estados acepta delegar ciertas competencias a un organismo común supraestatal. Basten, por ahora, estas nociones rudimentales.

Schmitt se forma en un medio jurídico-político donde las ideas de lo federal y confederal están vivas y presentes. Después de todo, aquéllas toman entidad en la Lotaringia y el Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico, donde se desarrollan aldeas, ciudades y comunas, cada una de ellas con objetivos y alcances propios, sin perjuicio de estar relacionadas con los conjuntos más amplios del reino o el imperio, originándose así la idea de la unidad como una "concordia armoniosa", presente en el pensamiento medieval[1]. Cuando Napoleón derriba al antiguo imperio alemán, comprende que los múltiples principados alemanes no pueden sobrevivir aislados y, para organizar la Mitteleuropa, crea, bajo su protectorado, la Confederación del Rhin (1806-1813), excluída Prusia.. A la caída de Napoleón, se establece la Confederación Germánica (1815-1866), integrada por treinta y ocho estados soberanos donde se cuentan un Imperio (Austria) y cinco reinos (Prusia, Baviera, Wurtemberg, Sajonia y Hannover). El II Reich alemán se organiza en 1871 como un Estado federal, formado por veinticinco estados federados bajo hegemonía prusiana. El Consejo federal, o Bundesrat, estaba presidido por el rey de Prusia, que llevaba el título de emperador de Alemania y designaba al canciller del Reich. La República de Weimar de 1919, es federal, parlamentaria y democrática, si bien los Länder retenían facultades limitadas. En fin, sean cuales fueren las limitaciones y problemas que manifestaron estas confederaciones y federaciones, lo cierto es que un jurista, en la Alemania de principios del siglo XX, no podía evitar la reflexión inmediata sobre el federalismo[2].

En la vasta obra schmittiana, sólo hay dos textos donde se desarrolla su pensamiento sobre el federalismo. El primero es la "Teoría de la Constitución", Verfassungslehre, publicada en 1928. La otra, aparecida en 1931, aunque reúne estudios publicados ya en 1929, es "El Guardián de la Constitución", Der Hütter der Verfassung. Reseñemos lo que ambas dicen sobre nuestro tema.

El primero, "Teoría de la Constitución", es la única obra de Schmitt concebida y desarrollada mediante el formato del tratado jurídico convencional y clásico. Podría pensarse en un desafío de nuestro jurista renano a sus colegas más reconocidos de la época: escribo en igual molde que ustedes, diciendo todo lo contrario de lo que inveteradamente repiten ustedes. Schmitt, que fue, al fin de cuentas, más jurista -más Kronjurist- de la república de Weimar que del Tercer Reich, donde terminó como un outsider, construye esta obra como una empresa de demolición del Estado de derecho, esto es, del tipo de Estado que la constitución weimariana pretendía más adecuadamente reflejar. Ella, sin embargo, lo convierte, paradójicamente, en uno de los mejores y más agudos expositores de los aspectos del Rechtstaat en general más descuidados por los análisis habituales[3].

Hasta ese momento, y salvo la opinión de Max von Seydel, sobre la que se apoya nuestro autor, la teoría dominante contraponía la confederación de Estados -Staatenbund- (al modo de la Confederación de 1815) al Estado federal -Bundstaat- (como el II Reich de 1871). Para Schmitt, en cambio, no existen diferencias entre ambas formas.

Para él, "federación [en el sentido amplio y abarcativo señalado] es una unión permanente, basada en libre conveniencia y al servicio del fin común de la autoconservación de todos los miembros, mediante la cual se cambia el total status político de cada uno de los miembros en atención al fin común"[4]. La federación da lugar a un nuevo status jurídico-político de cada miembro. El pacto federal es un pacto interestatal de status con vocación de permanencia (toda federación es concertada para la "eternidad", esto es, para la eternidad relativa de toda forma política, mortal por definición).

Toda federación, según nuestro autor, reposa sobre tres antinomias o contradicciones:

-

Derechode autoconservación vs. renuncia al ius belli.

-

Derechode autodeterminación vs. Intervenciones.

-

Existenciasimultánea, por un lado. de la federación común y, por otro, de los estados miembros.La esencia de la federación reside, pues, en un dualismo de laexistencia política. Tal coexistencia de una unidad políticageneral y de unidades políticas particulares da lugar a unequilibrio difícil. Se presenta, ante todo, elproblema de la soberanía: ¿serán soberanos los estados federadosy no la federación? ¿o la federación es la únicasoberana y los estados federados carecen de tal atributo?. Se tratade soberanía, es decir, de una decisión (soberano es el que decidesobre el estado de excepción; en este caso, el que decide sobre su propia existencia política o, invirtiendo la fórmula, acerca deque un extraño no decida sobre su propia existenciapolítica). Si la decisión es deferida a un tribunaljudicial, éste se tornaría inmediatamente soberano, en otraspalabras, poder político existencial. La respuesta, según nuestroautor, tampoco puede consistir (según la teoría corriente en sutiempo, y vigente entre nuestros constitucionalistas) en ladistinción entre confederación y federación: en la confederación los estados federados son soberanos y en el Estado federal lasoberanía reside en la federación misma. Ya hemos visto su rechazode esa distinción, que no tiene en cuenta -afirma - cómosurge una decisión soberana en caso de un conflicto en que esté enjuego la propia existencia de la forma política en cuestión. Enpuridad, dice Schmitt, conforme aquel criterio dominanteresulta que la confederación se disuelve siempre en caso deconflicto, y que la federación se resuelve siempre, cuando mediaconflicto, en un Estado unitario. Schmitt, citándolo a través delos escritos de Max von Seydel, se refiere a las doctrinas de JohnCalhoun, que sirvieran a la argumentación de los confederadossudistas[5].Calhoun no admitía que, al sancionarse en Norteamérica laconstitución federativa de 1787, los estados federados hubiesenrenunciado a sus derechos soberanos, los State Rights,anteriores a la federación y en principio ilimitados, salvo lascompetencias que expresamente se delegaron en la constitución.Calhoun, como Seydel hará suyo, sostiene que una suma decompetencias delegadas no transmite soberanía al delegado, niimplica renuncia a ella por parte del delegante. Los estadosfederados conservaban, pues, un derechoa la anulación delas leyes y actos federales y, cuando estuviese comprometida suseguridad y existencia, un derechoa la secesión (loque condujo a la guerra civil de 1861-65). Derrotada esa posiciónen el campo de batalla (a partir de allí anulación ysecesión equivalen a rebelión y sobre las cuestiones entre estadosfederados decide en último término la Corte Suprema) no queda,según Schmitt, refutado por ello el argumento calhouniano. Lo queocurre es que la Constitución como tal ha cambiado su carácter yla federación ha cesado: subsiste tan sólo una autonomíaadministrativa y legislativa de los estados federados; en otraspalabras, una seudofederación.

A continuación, nuestro autor se plantea cómo se diluyen las antinomias que afectan a la federación. La federación supone homogeneidad de todos sus miembros. Para Montesquieu, esta homogeneidad significaba que los federados fueran estados republicanos, es decir, que tuviesen homogeneidad de organización política. La homogeneidad podría ser, también, de nacionalidad, de religión, de civilización etc. Schmitt parece privilegiar la homogenidad nacional de la población, esto es, para él, la homogeneidad de origen.

Así, la primera antinomia (derecho a la autodefensa y renuncia al ius belli) se diluye porque la homogenidad con los otros federados excluye la la hostilidad entre ellos.

La segunda antinomia (autonomía e intervención) se disuelve porque la voluntaCarl Schmitt y el Federalismo - SILACPOd de autodeterminación se plantea frente a una ingerencia extraña, pero no resulta extraña la de la propia federación.

La tercera antinomia (dualismo existencial entre federación soberana y estados miembros soberanos) se disuelve porque la homogeneidad excluye el conflicto existencial decisivo. Como las cuestiones de la existencia política pueden presentarse en campos diversos, se da así la posibilidad de que la decisión de una clase de cuestiones tales como, por ejemplo, de la política exterior, competa a la federación y que, por el contrario, la decisión de otras, por ejemplo, mantenimiento de la seguridad y el orden público dentro de un estado federado, quede reservada al propio estado miembro. No se trata de una división de la soberanía, porque en caso de una decisión que afecte a la existencia política como tal, la tomará por entero sea la federación, sea el estado miembro[6]. Donde hay homogeneidad, el caso de conflicto decisivo entre la federación y los estados miembros debe quedar excluída. De otro modo, el pacto federal se convierte en un "seudonegocio jurídico nulo y equívoco"[7].

El traductor español de la obra, Francisco Ayala, apunta en el prólogo, respecto de esta conclusión: "se las ingenia de manera a asegurar que tanto las federaciones como los estados miembros aparezcan al mismo tiempo como unitarios y soberanos". Pero Schmitt, en verdad, está señalando como propio de toda organización federativa la tensión conflictual entre federación y federados, que puede llegar al pico de la situación excepcional y resolverse por decisión soberana de la primera o de los segundos. Las antinomias que están en la base de esa tensión conflictual pueden diluirse, para Schmitt, mientras la homogeneidad que ha llevado al foedus o pacto originario, en cuya virtud ha cambiado el status de los federados, se mantenga. En el momento en que alguno de los federados sienta su propia existencia amenazada porque aquella homogeneidad se ha roto o no es reconocido como integrándola, entonces, o el foedus se revelará como pacto de origen de un Estado, en el fino fondo, "uno e indivisible", o será quebrado por ejercicio de los derechos de anulación y secesión. En otras palabras, en el primer caso, ante la situación excepcional, la federación ejerce la soberanía irrenunciable y deviene, en los hechos, un Estado centralizado y, en el segundo, el acto soberano proviene del estado federado, que rompe la federación. La Ausnahmezustand, la situación o estado de excepción, en ese caso, y cualquiera sea quien protagonice la decisión (federación o estado federado), da lugar al acto soberano y consecuente re-creación de un nuevo orden jurídico[8]. De todos modos, las circunstancias bien apuntadas por Schmitt no significarían una debilidad especial de la federación con respecto a otras formas de articulación territorial del poder. Basta observar el Estado unitario descentralizado italiano o español ("Estado de regiones" o "Estado de las autonomías"), o el caso del Reino Unido de la Gran Bretaña, para advertir la misma tensión existencial entre Estado central y comunidad particular que nuestro autor apunta como meollo antinómico y foco conflictivo de la federación, con situaciones extremas y excepcionales cual el Ulster o el País Vasco. Hasta en Francia, república "una e indivisble" por antonomasia, apunta, sobre otros, el caso inmanejable de Córcega. A tal punto que Raymond Barre, ex primer ministro francés, medio en broma medio en serio, proponía devolvérsela a Génova.

Volvamos a nuestro autor. Nos ha presentado las dificultades mayúsculas y tensiones conflictivas que, a su juicio, aparecen allí donde una federación exista. Luego aparenta disolverlas acudiendo al recurso de la homogeneidad, especialmente la homogeneidad de origen, la homogeneidad nacional de un pueblo. Pero a continuación, nos plantea una nueva dificultad, en la que aquella homogenidad amenaza destruir la federación. Se trata de una antinomia sobreviniente, que enfrenta a democracia y federalismo.

A mayor democracia, menor esfera propia de los Estados federados. Democracia y federación descansan, ambas, en el supuesto de la homogeneidad. El pensamiento de Schmitt, como se sabe, apunta en este aspecto a separar la noción de democracia de la noción de Estado liberal-burgués. Democracia, para Schmitt, es una forma política que corresponde al principio de identidad entre gobernantes y gobernados, de los que mandan y de los que obedecen, dominadores y dominados, esto es, identidad del pueblo y de la unidad política. Ello por la sustancial igualdad que es su fundamento y que supone, parejamente, una básica homogeneidad, en el pueblo. Por ello, en el desarrollo de la democracia dentro de una federación, la unidad nacional homogénea del pueblo transpasará las fronteras políticas de los Estados federados y tenderá a suprimir el equilibrio de la coexistencia de federación y estados federados políticamente independientes, a favor de una unidad común.

Ello conduce a un "Estado federal sin fundamentos federales"[9], como los EE.UU. o la República de Weimar, según nuestro autor. En ellos, la constitución toma elementos de una anterior organzación federal y expresa la decisión de conservarlos, pero el concepto democrático de poder constituyente de todo el pueblo, a juicio de Schmitt, suprime el concepto de federación. Se organiza un complejo sistema de distinción de poderes y descentralización, pero falta el fundamento federativo: hay una unidad política (la unidad política de un pueblo en un Estado) y no una pluralidad de unidades políticas, que es lo que supone la federación propiamente dicha. No existe, apunta Schmitt, un pueblo bávaro, prusiano, hamburgués en la constitución de Weimar: sólo existe el pueblo alemán. Sin embargo, la contradicción entre democracia y federación, donde la consecuencia de la primera, el poder constituyente del pueblo uno y único, socava los fundamentos de la segunda, no parece haber afectado a Suiza, por ejemplo. Una respuesta más afinada nos la dará Schmitt en la segunda obra donde se encuentran referencias al federalismo: Der Hüter der Verfassung.

En ella, sostiene que el presidente es el custodio de la constitución, como poder neutro y super partes. No podría serlo un tribunal judicial o corte constitucional porque, en ese caso, se le trasladaría la decisión soberana, convirtiéndose la Corte Suprema o el Consejo Constitucional en soberanos "legisladores negativos" (la expresión es de Kelsen). Detalla los peligros concretos que acechan a la defensa de la constitución que asigna al presidente del Reich. Por un lado, la existencia de partidos dotados de Weltanschauungen o cosmovisiones totales y encontradas (el nacionalsocialismo y el comunismo), es decir, partidos totalitarios. Cada uno de ellos trata de arrebatarle al Estado su prerrogativa propiamente política, esto es, trazar la línea divisoria entre el amigo y el enemigo. Al lado de estos partidos totalitarios, se manifiestan coaliciones parlamentarias lábiles, que acentúan tendencias pluralistas, es decir, para nuestro autos, fragmentantes de la unidad política. También contribuye a desarticular el Estado weimariano, prosigue nuestro autos, el "policratismo" de los diversos sectores de la economía pública (correo, ferrocarriles, Reichbank, etc.) que se mueven cada uno independientemente del otro y hasta chocando entre sí. Por otra parte, al haberse dado la república de Weimar una organización al mismo tiempo parlamentaria y federal, continúa nuestro autor, resurge la antinomia ya señalada en Verfassungslehre entre federalismo y democracia. Schmitt no oculta que la organización federativa de la república de Weimar le parece desestabilizante para el Estado, y la función presidencial de guardián de la constitución. Este peligro se acentúa cuando federalismo y pluralismo político se refuerzan mutuamente, consiguiéndose, dice nuestro jurista, "un doble quebrantamiento del hermetismo y de la solidez de la unidad estatal" En un Estado al mismo tiempo federal y parlamentario el federalismo, según nuestro autor, puede justificarse sólo de dos maneras:

-

Comorecurso de auténtica descentralización territorial, contra lospoderes pluralistas y policráticos enquistados en el gobierno y enla actividad económica.

-

Como"antídoto contra los métodos peculiares del pluralismo de lospartidos" [10].Esta última es una observación de gran actualidad: la realidad deun sistema de articulación territorial del poder reside en elsistema de partidos. Con partidos nacionales de direccióncentralizada, como en el caso de nuestro país, y más aún con sistemas electorales donde tales partidos monopolizan larepresentación y la manejan a través de listas cerradas,reduciéndose así, poco a poco, la democracia a un ejercicioautorreferencial de lo que se ha llamado el englobante "partidode los políticos", la variedad de las comunidades federadas sediluye en cacicazgos locales dentro de los bloques partidarios. Otra consecuencia es la aparición defensiva de partidosparticularistas, como se ve en España, Italia, Escocia, etc., comoreacción simétrica a lo anterior. Por lo tanto, y esto explica lainaplicabilidad, en principio, de la reflexión schmittiana enVerfassungslehre al caso suizo, la antinomia más virulenta se daríaentre federación y democracia monopolizada por partidos nacionalesy centralizados.

Muchos conocedores de Schmitt sostienen que, si bien advirtió la declinación del Estado-nación como forma política, jamás pudo superar el horizonte teórico estatalista. José Caamaño Martínez afirma, por ejemplo, ante la dúplice soberanía que otorga nuestro autor a la federación y a los miembros federados: "esta teoría de la federación nos muestra claramente que la forma histórica del Estado nacional unitario sigue siendo un dogma del pensamiento de Schmitt"[11].

"No deja lugar -dice Francisco por su parte Ayala- a un tipo de organización de la convivencia política distinto del Estado nacional [centralizado]"[12].

Gary Ulmen, por su lado, resume así la cuestión: Schmitt consideraba sustancialmente al federalismo como una fase del pasaje entre el mundo plural y parcializado de los Estados Naciones y el mundo contemporáneo, que tiende a la unidad homogeneizante. Schmitt plantea en el federalismo algunas antinomias fundamentales: partiendo del presupuesto que una federación es un contrato de status entre unidades más o menos iguales, que adhieren a la federación con finalidad de mutua protección, gestión e integración, conlleva una permanente tensión entre la autonomía de las unidades federadas y la intervención federal. Con el tiempo, la mayor fuerza de la federación respecto de las unidades federadas producirá una creciente centralización, mientras que la heterogeneidad de las diversas unidades (ej. los EE.UU) choca con el principio democrático del pueblo soberano, que trasciende las diferencias entre los Estados miembros y tiende a una única homogeneidad. En ese punto la contradicción se manifiesta insoluble: sin homogeneidad la federación democrática no puede funcionar, pero si la homogeneidad se logra, las diferencias resultan superadas y, de hecho, se realiza un Estado unitario. Un proceso, pues, de gradual reductio ad unum [13].

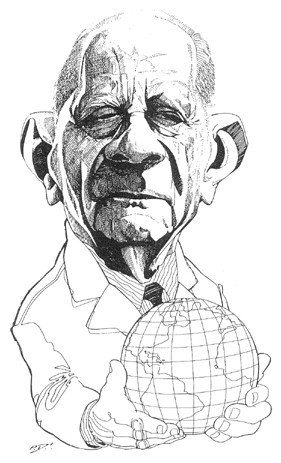

En Schmitt hay una permanente tensión entre la nostalgia del jus publicum europaeum, derecho público interestatal, y su percepción de la declinación de la forma estatal. Es muy claro respecto a esto último cuando prologa la reedición de "El Concepto de lo Político":

"Hasta los últimos años la parte europea de la Humanidad vivió una época cuyas nociones jurídicas eran acuñadas desde el punto de vista estatal. Se supuso al Estado modelo de la unidad política. La época del estatismo está terminando ahora. No vale la pena discutirlo. Con ello se termina toda la infraestructura de construcciones relacionadas con el Estado, que una ciencia europeo-céntrica del derecho internacional y del derecho político había erigido en cuatrocientos años de trabajo espiritual. Se destrona al Estado como modelo de la unidad política, al Estado como portador del monopolio de la decisión política. Se destrona a esta obra maestra de la concepción europea y del racionalismo occidental. Pero se mantienen sus nociones e incluso se mantienen como ideas clásicas, aunque hoy día la palabra clásico suena casi siempre equívoca y ambivalente, por no decir irónica"[14]. Se advierte, junto a la claridad de la toma de posición, el tono elegíaco respecto de la época que se cierra y un pronóstico ominoso respecto de la que se abre. Hay una cierta renuencia a pensar más allá de la forma estatal. Nuestro autor es claro, preciso y de seguimiento ineludible en cuanto a la pars destruens respecto de lo que asoma tras la retirada de la estatalidad y el jus publicum europaeum, donde aquélla se expresaba. Recoge la frase de Proudhon, "quien dice Humanidad quiere engañar" y alerta sobre la intensificación de la enemistad hacia posiciones absolutas que encubre el interventismo humanitarista. Pero, a la vez, desde la pars construens, no alcanza a concebir una pluralidad superadora de la estatalidad moderna, un orden jurídico postestatal, tanto hacia adentro del Estado y la articulación terriotorial del poder, como hacia fuera de los Estados, que suceda sin traicionar en lo esencial y valioso aquel jus publicum moribundo. Para Schmitt, la unidad política estatal fue el unum necessarium; ahora, marchamos hacia una unidad política de alcance planetario, que no podría cumplir con lo que el Estado consiguió ad intra: la paz interior, la deposición de la enemistad intestina; en otras palabras, se perdería, a escala global, el vivere civile, la dimensión civilizatoria de la política. Pero a Schmitt no le interesó jamás cómo se articulaba hacia adentro, funcional y territorialmente, aquella paz interior. Lo seduce la unitas, pero no lo atrae la universitas donde se articulan diversidades y diferencias. Así, deja a un lado la corriente de pensamiento medieval, con culminación en Dante, luego reaparecida con Altusio, que resulta basilar para la noción federativa. Los jurisconsultos del medioevo hablaban de una bóveda de universitates locales ordenadas desde el domus, el vicus, la civitas, la provincia, el regnum, el imperium. Es probable que nuestro autor viese en esta corriente una manifestación del romanticismo político que solía fulminar. Así, por ejemplo, en las fórmulas de Adam Müller acerca de una concepción "orgánica" y estamental del Estado como una comunidad superior de comunidades, transmitidas por la obra de Gierke y recogidas por un contemporáneo de Schmitt, Othmar Spann. Schmitt polemizó en varias ocasiones con las teorías organicistas que asimilaban el Estado a las otras comunidades, tanto las menos como las más amplias, afectando así la summa potestas del soberano[15]. En "El Concepto de lo Político" (1927) hace referencia expresa a Gierke, cuya teología política, según nuestro autor, en la búsqueda de una unidad última, de un "cosmos' y de un "sistema" resulta "superstición y reminiscencia de la escolástica medieval"[16]. En "El Leviatán en la Teoría del Estado de Tomás Hobbes" (1938) señala que los mecanismos estamentales, generadores de un derecho de resistencia, conducen a la guerra civil, cuando la misión del Estado es ponerle un cierre definitivo[17]. Pero su ataque se concentró, especialmente, sobre las concepciones pluralistas de Harold Laski y G.D.H. Cole, que, entre 1914 y 1925, habían propiciado, desde posiciones cercanas al socialismo inglés y los fabianos, la descentralización y repartición del poder estatal. Aunque las notas polémico de Schmitt son de 1927[18], cuando Laski ya había abandonado el pluralismo o policratismo, le servían a nuestro autor para reafirmar su pensamiento nuclear de rechazo de toda forma de contestación o recorte de la superioridad ad intra del Estado.

Nuestro autor, como se sabe, desde los años 40 comienza a hablar de los imperios y de los grandes espacios, los Grosseraume, como las formas políticas surgentes tras la estatalidad. El mundo quedaría parcelado en una pluralidad de grandes espacios, pero como pluralidad de unidades estancas. Habría, en otras palabras, un nuevo jus publicum con menos protagonistas que el antiguo: "un equilibrio de varios grandes espacios que creen entre sí un nuevo derecho de gentes en un nuevo nivel y con dimensiones nuevas, pero, a la vez, dotado de ciertas analogías con el derecho de gentes europeo de los siglos dieciocho y diecinueve, que también se basaba en un equilibrio.de potencias, gracias al cual se conservaba su estructura"[19]. Nada nos dice de cómo se organizarían ad intra los grandes espacios: súlo sabemos que deberían mantener alguna homogeneidad interna y que algún Estado ejercería en ellos un papel hegemónico (el ejemplo es el papel de los EE.UU respecto al resto de América, luego de que la doctrina Monroe estableciera límites y exclusiones configuradoras de este gran espacio).

Los Grosseraume se plantean como alternativa al gran peligro, a la remoción del katéjon (es decir, lo que retiene, ataja u obstaculiza, concepto recurrente en la teología política final de nuestro autor). El katéjon actúa en toda época y es, por lo tanto, variable con el decurso de aquéllas. El katéjon asienta o mantiene el Nomos epocal y desaparece con él[20]. Se lo menciona en Pablo de Tarso (II epístola a los tesalonienses, 2, 6/7), que lo considera el obstáculo o retardo, qui tenet nunc, el que retiene ahora la manifestación del Anticristo. El Anticristo de Schmitt es la soberanía global, el mundo uno y uniforme correspondiente al pensamiento técnico-industrial. El sistema de Estados nacionales en pugna controlada, construcción de la racionalidad europea, edificadores al mismo tiempo, cada uno, de su propia paz interior, he allí el verdadero katéjon para Schmitt. Ninguna virtualidad le ve en ese sentido a la provisoria federación, contrato temporario de status, fuente de desestabilizaciones, que prefiere mostrar a contraluz o no mostrar, como dijimos al principio de este trabajo. Aunque, a pesar de su desconfianza hacia las formas federativas, dejó sobre ellas notables observaciones jurídico-políticas, como hemos visto. Quizás, alguien ha señalado, se consideraba el mismo Schmitt como el katéjon intelectual al diseño maligno de la soberanía global desde la unidad política del mundo. De todos modos, advierte que un Nomos de la tierra desaparece y no ha apuntado el otro todavía. No alcanza a divisar si es posible un nuevo Nomos pluralístico donde la conflictualidad se canalice y yugule, sin proclamar su desaparición, como sueña la soberanía global mientras desarrolla sin pausa sus operaciones de policía humanitaria.

Schmitt advertía una sustancial oposición entre estatalidad y federalismo. Por eso decía que el Estado federal, seudonegocio jurídico nulo y equívoco se resuelve, como el federalismo hamiltoniano, en la forma de Estado unitario más o menos matizado. Hoy reaparece el federalismo de raíz lotaringio germánica, cuyo teórico más reciente fuera Proudhon, como visión comprensiva del mundo y de la sociedad, no como simple forma de Estado (su fórmula podría ser, en lugar de e pluribus, unum, del federalismo norteamericano, la de ex uno, plures[21]). El katéjon schmittiano está removido. Una soberanía global es posible. Hasta hace poco, se pensaba que esa soberanía residía impersonal y ubicuamente en los mecanismos, soportes y programas autosuficientes de las redes tecnológicas, de comunicación, informáticas y financieras que rodean el planeta[22]. Al no haber un Leviatán visible, se lo suponía muerto o dormido. Después del 11 de septiembre de 2001, Leviatán debe manifestarse otra vez, ahora para asegurar el globo ante la amenaza del terrorismo global y "privatizado". En esa bufera o borrasca dantesca nos toca movernos, y las reflexiones schmittianas permiten allí algunos vislumbres. Decía Hölderlin que en el peligro crece también lo que salva. Y nuestro autor agregaba que, al borde del abismo, en la situación excepcional, "la mente se abre al arcano".

* Doctor en Ciencias Jurídicas, Universidad Católica Argentina.

NOTAS

[1]) Ver Otto von Gierke, "Teorías Políticas de la Edad Media",con introducción de F.W. Maitland, traducciónindirecta del ingléspor Julio Irazusta, Editorial Huemul, Bs. As., 1963, p. 108/109.

[2] )Tras la Segunda Guerra Mundial, la República Federal Alemana seconfiguró en 1949, como su nombre lo indica, bajo un sistemafederativo. La República Democrática Alemana, en cambio, como"Estado socialista de la nación alemana", se configuróbajo un sistema unitario. Anteriormente, bajo el III Reich, la Leyde Plenos Poderes del 24 de marzo de 1933, que en los hechos derogóla Constitución de Weimar, otorgó la potestad legislativa laGobierno del Reich, es decir, al Fuehrer., que designaba algobernador (Gauleiter) en cada uno de los distritos. La organizacióndel Reich fue asimilándose (Gleichschaltung) a la organizacióncentralizada y uniforme del Partido Nacional Socialista ObreroAlemán. Alemania, hoy, es un Estado federal.

[3] )Ver Carl Schmitt, "La Defensa de la Constitución", trad.de Manuel Sénchez Sarto, prólogo de Pedro de Vega, ed. Tecnos,Madrid, 1998, 2ª. Edición, p. 12

[4] )Carl Schmitt, "Teoría de la Constitución", traducción ypresentación de Francisco Aala, epílogo de Manuel García-Pelayo,Alianza editorial, Madrid, 1982, p. 348.

[5] )Schmitt solía adherir a la causa de los vencidos: victrix causadiis placuit, sed victa Catoni,la causa de los vencedores place alos dioses, pero la de los vencidos a Catón..y a Schmitt.

[6] )Contra James Madison en "El Federalista", XXXIX, XLIV yXLV: se propone una soberanía distributiva, donde los estadosfederados retienen una porción no delegada, un residuo inviolable,y la federación ejerce sólo la delegada. Ello es posible porque elpueblo, organizado en ciudadanía, no en masa, manifiesta suvoluntad soberana parcialmente en varias represdentaciones: comoindividuo, como miembro del estado federado, como miembro de lafederación. Ver Hamilton, Madison y Jay, "El Federalista",prólogo y traducción de Gustavo R. Velasco, FCE, Mexico,6ª.reimpresión, 1998. Para Schmitt, este deslinde, esta especie definium regundorum entre federación y estados miembros de la mismasoberanía, no resulta concebible. En la situación excepcional,quien decida, federación o estado miembro, resulta plenamentesoberano.

[7] )Op. cit. n. iv, p. 359

[8] )Sobre las dificultades de traducción de Ausnahmezustand como"estado" o "situación" excepcional puede versela nota del traductor, Jean-Louis Schlegel en "ThéologiePolitique, 1922,1969", Gallimard, 1988, p. 15. Para otrosdesarrollos sobre el concepto de soberano en Schmitt me remito a miprólogo a "Teología Política", Ed. Struhart y Cía.,2ª. Ed., Bs. As. 1998.

[9] )Op. cit nota iv, p. 369.

[10] )Op. cit. n. iii, p. 161.

[11] )José Caamaño Martínez: "El Pensamiento Juídico-Político deCarl Schmitt", prólogo de Luis Legaz y Lacambra, Ed. Porto yCía, Santiago de Compostela, 1950, p. 159.

[12] )Op. cit. n iv, p. 17

[13] ) Gary L. Ulmen en Paul Piccone y otros, "La RivoluzioneFederalista", Settimo Sigillo, Roma, 1995.

[14] )Carl Schmitt, "La Noción de lo Político", en Revista deEstudios Políticos, Instituto de Estudios Políticos, nº 132, Madrid, noviembre-diciembre 1963, p.6

[15] )Una de ellas fue en una conferencia de 1930 en honor de Hugo Preuss,discípulo de Gierke. Ver George Schwab, "Carl Schmitt, lasfida dell'eccezione", introducción de FrancoFerrarotti, traducción de Nicola Porto, Laterza, Bari, 1986, p.92

[16] )Carl Schmitt, "El Concepto de lo Político", trad. deFrancisco Javier Conde, en "Estudios Políticos", Doncel,Madrid, 1975, p. 118.

[17] ) Carl Schmitt, "El Leviatán en la Teoría del Estado de TomásHobbes", traducción de Francisco Javier Conde, Ediciones Haz,Madrid,1941 p. 72/73.

[18] )Op. cit. nota anteror, loc. cit. Un eco de este ataque al pluralismo"extremista" del "judío Laski" aparece en "ElConcepto de Imperio en el Derecho Internacional" (1940), trad.de Francisco Javier Conde, Revista de Estudios Políticos, Madrid,1941, p. 97.

[19] )Carl Schmitt, "La Unidad del Mundo", Ateneo, Madrid, 1951,p.24

[20] )Carl Schmitt, "El Nomos de la Tierra en el Derecho de Gentesdel jus publicum europaeum", trad. Dora Schilling Thon,Estudios Internacionales, Madrid, 1979, p. 37 y sgs.

[21] )Me remito a mi trabajo "El Federalismo Argentino en elNovecientos o de cémo perdimos el siglo", IV Congreso Nacionalde Ciencia Política, UCA -SAAP, Buenos Aires, RA, noviembre 17 al20 de 1999,.

[22] )Ver Bandieri, Luis María, "¿Soberanía Global vs. SoberaníaNacional? (Hacia una Micropolítica Federativa)" Ponencia en laPrimeras Jornadas nacionales de derecho Natural, San Luis, RA, 14 al16 de junio de 2001, RA

Si le nom de Carl Schmitt n’est plus tout à fait inconnu en France, où plus d’une dizaine de ses ouvrages ont déjà été traduits depuis 1972, sa personnalité reste encore très controversée. Grand théoricien du droit constitutionnel et international de l’Allemagne de l’entre deux guerres, son attitude à l’égard du nazisme lui valut d’être emprisonné plus d’une année après 1945. Refuser d’aller plus loin serait pourtant regrettable, comme ceux qui voudront bien ouvrir Le nomos de la terre s’en rendront rapidement compte. Publié en 1950 et composé dans des conditions difficiles, ce gros ouvrage offre une vue d’ensemble sur la pensée de l’auteur et passe à bon droit pour son oeuvre maîtresse.

Si le nom de Carl Schmitt n’est plus tout à fait inconnu en France, où plus d’une dizaine de ses ouvrages ont déjà été traduits depuis 1972, sa personnalité reste encore très controversée. Grand théoricien du droit constitutionnel et international de l’Allemagne de l’entre deux guerres, son attitude à l’égard du nazisme lui valut d’être emprisonné plus d’une année après 1945. Refuser d’aller plus loin serait pourtant regrettable, comme ceux qui voudront bien ouvrir Le nomos de la terre s’en rendront rapidement compte. Publié en 1950 et composé dans des conditions difficiles, ce gros ouvrage offre une vue d’ensemble sur la pensée de l’auteur et passe à bon droit pour son oeuvre maîtresse.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Since 1945 Western nations have witnessed a dramatic reduction in the variety of positions in political theory and jurisprudence. Political argument has been virtually reduced to contests within liberal-democratic theory. Even radicals now take representative democracy as their unquestioned point of departure. There are, of course, some benefits following from this restriction of political debate. Fascist, Nazi and Stalinist political ideologies are now beyond the pale. But the hegemony of liberal-democratic political agreement tends to obscure the fact that we are thinking in terms which were already obsolete at the end of the nineteenth century.

Since 1945 Western nations have witnessed a dramatic reduction in the variety of positions in political theory and jurisprudence. Political argument has been virtually reduced to contests within liberal-democratic theory. Even radicals now take representative democracy as their unquestioned point of departure. There are, of course, some benefits following from this restriction of political debate. Fascist, Nazi and Stalinist political ideologies are now beyond the pale. But the hegemony of liberal-democratic political agreement tends to obscure the fact that we are thinking in terms which were already obsolete at the end of the nineteenth century.

In a certain sense, there have been total wars at all times; a theory of the total war, however, presumably dates only from the time of Clausewitz who would talk of “abstract” and “absolute” wars.”[1] Later on, under the impact of the experiences of the last Great War, the formula of total war has acquired a specific meaning and a particular effectiveness. Since 1920, it has become the prevailing catchword. It was first brought out in sharp relief in the French literature, in book titles like La guerre totale. Afterwards, between 1926 and 1928, it found its way into the language of the proceedings of the disarmament committee at Geneva. In concepts such as “war potential” (potentiel de guerre), “moral disarmament” (désarmement moral) and “total disarmament” (désarmement total). The fascist doctrine of the “total state” came to it by way of the state; the association yielded the conceptual pair: total state, total war. In Germany, the publication of the Concept of the Political has since 1927 expanded the pair of totalities to a set of three: total enemy, total war, total state. Ernst Jünger’s book of 1930 Total Mobilization made the formula part of the general consciousness. Nonetheless, it was only Ludendorff’s 1936 booklet entitled Der Totale Krieg (The Total War) that lent it an irresistible force and caused its dissemination beyond all bounds.

In a certain sense, there have been total wars at all times; a theory of the total war, however, presumably dates only from the time of Clausewitz who would talk of “abstract” and “absolute” wars.”[1] Later on, under the impact of the experiences of the last Great War, the formula of total war has acquired a specific meaning and a particular effectiveness. Since 1920, it has become the prevailing catchword. It was first brought out in sharp relief in the French literature, in book titles like La guerre totale. Afterwards, between 1926 and 1928, it found its way into the language of the proceedings of the disarmament committee at Geneva. In concepts such as “war potential” (potentiel de guerre), “moral disarmament” (désarmement moral) and “total disarmament” (désarmement total). The fascist doctrine of the “total state” came to it by way of the state; the association yielded the conceptual pair: total state, total war. In Germany, the publication of the Concept of the Political has since 1927 expanded the pair of totalities to a set of three: total enemy, total war, total state. Ernst Jünger’s book of 1930 Total Mobilization made the formula part of the general consciousness. Nonetheless, it was only Ludendorff’s 1936 booklet entitled Der Totale Krieg (The Total War) that lent it an irresistible force and caused its dissemination beyond all bounds.