samedi, 25 mai 2019

Les routes de la soie au prisme du néo-eurasisme de Douguine : retour de Béhémoth ou triomphe du Léviathan ?

Les routes de la soie au prisme du néo-eurasisme de Douguine : retour de Béhémoth ou triomphe du Léviathan ?

« La Grande Eurasie n’est pas un arrangement géopolitique abstrait, mais, sans exagération, un projet à l’échelle civilisationnelle, tourné vers l’avenir.»

Vladimir Poutine, mai 2017

« L’histoire mondiale est l’histoire de la lutte des puissances maritimes contre les puissances continentales et des puissances continentales contre les puissances maritimes »

Carl Schmitt, 1942

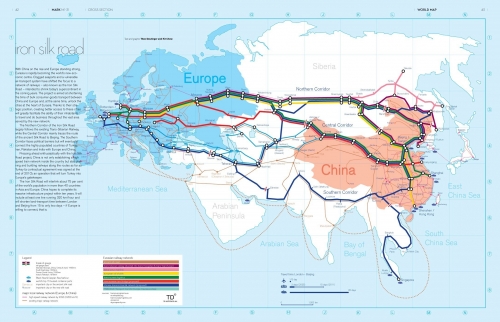

Au cœur de la stratégie politique et commerciale internationale de la Chine depuis 2013, le système multi-vectoriel de projets des nouvelles routes de la soie (appelé officiellement Belt and Road Initiative, BRI1 depuis mai 2017), qui souhaite connecter les économies chinoises, européennes, africaines et centre-asiatiques par une densification des réseaux d’infrastructures de transports et de communication, se concrétise chaque jour un peu plus sérieusement. Avec ses différents volets (construction d’infrastructures terrestres et maritimes, coopération économique, énergétique et sociétale), c’est sans doute l’entreprise la plus ambitieuse au monde et, au vu du potentiel de développement économique et des implications géopolitiques qu’elle comporte2, elle suscite de plus en plus de partenariats.

Le 9 avril dernier s’est ainsi tenu à Bruxelles le 21ème sommet Chine-Union Européenne, occasion pour l’UE de déterminer une position commune vis-à-vis de la BRI et de discuter des synergies possibles avec son plan européen de connectivité Europe-Asie4, alors que, l’une après l’autre, les nations européennes signent bilatéralement des engagements dans le projet5.

Bien plus que les timides rapprochements des Européens, c’est la perspective de l’édification d’un axe Moscou-Pékin autour de cette initiative qui soulève les analyses géopolitiques les plus audacieuses : Ressurgirait la vieille menace, préfigurée par Mackinder en 1904 dans les propos concluants son « Pivot géographique de l’histoire »6, d’une Chine qui offrirait aux ressources immenses du continent une large façade océanique (ce qui caractérisait pour lui le véritable « péril jaune » menaçant la liberté du monde). En somme un « empire terrien eurasiatique » dominant le Heartland pourrait émerger et reléguer les puissances maritimes occidentales au second rang dans la rivalité générale pour la domination mondiale.Un tel traitement nous ramènerait aux fondamentaux de la discipline par une réappropriation de la dialectique Terre-Mer pour analyser le phénomène routes de la soie. Elle fascine toujours autant de par sa dimension symbolique et son caractère quelque peu réducteur, la rendant accessible au plus grand nombre.

Cela dit, il est vrai que depuis 2014 Russie et Chine ont opéré un rapprochement bilatéral notable7 et coopèrent de plus en plus activement au travers de la BRI : ainsi en mai 2015 fut-il décidé que l’initiative d’intégration continentale portée par la Russie, l’Union économique eurasiatique (UEE), y soit raccordée8 et en novembre 2017 la « route maritime du Nord » est devenue un des corridors de la BRI9. On relève aussi l’imbrication de l’initiative avec le développement de la coopération sino-russe au sein de l’Organisation de Coopération de Shanghai (OCS)10.

De facto, une certaine unification continentale dans l’espace eurasiatique semble donc s’esquisser11. Ceci pourrait alors confirmer la portée heuristique persistante de la clé de lecture Terre-Mer. Mais c’est surtout lorsque l’on entre dans une géopolitique des perceptions que cette dialectique conserve sa pertinence : Il existe en effet un paradigme géopolitique affirmant explicitement la nécessité pour la Russie de briser l’hégémonie des puissances maritimes et de reconstituer une unité politique sur la masse continentale eurasiatique, notamment en développant un partenariat stratégique avec la Chine. Cette vision est portée par les auteurs constituant le mouvement d’idée du néo-eurasisme12. C’est une doctrine très en vue en Russie mais aussi dans d’autres États d’Asie Centrale, notamment au Kazakhstan où l’(ex-)président Nursultan Nazarbaev la soutient explicitement13.

Parmi les différents faisceaux composant le mouvement néo-eurasiste, un auteur se distingue : Alexandre Douguine14. Sa pensée, bien que plus marginale aujourd’hui, a connu ses heures de gloire et continue d’inspirer une partie des élites dirigeantes russes, tout en nourrissant bien des fantasmes chez les commentateurs étrangers15. S’il est issu de la pensée eurasiste classique, il y adjoint des filiations intellectuelles peu habituelles qui singularisent ses propositions, les amenant dans un registre métapolitique, métahistorique et culturaliste : Le monde des phénomènes n’est pour lui que le reflet des puissances archétypales qui le meuvent depuis l’invisible et sa pensée s’inscrit dans la bataille gramscienne16 pour l’« hégémonie culturelle »17.

Les analyses ne manquent pas pour venir questionner les convergences et les limites des projets russes et chinois au-regard des ambitions géopolitiques eurasistes, mais elles s’inscrivent généralement sur des plans stratégique, économique, financier, juridique. Dans cette étude, nous souhaiterions sortir de l’empire des faits pour plonger plus profondément dans le monde des idées. Nous proposerons une lecture du phénomène nouvelles routes de la soie à travers le prisme de la doctrine géopolitique d’Alexandre Douguine, en essayant de nous approprier son discours original, structurant la vision-du-monde de certains acteurs impliqués dans le complexe de la BRI.

Nous nous demanderons donc si la Belt and Road Initiative participe de la constitution d’un bloc continental eurasien face à la thalassocratie atlantiste compatible avec les fondamentaux proposés par Alexandre Douguine pour la politique étrangère russe.

Nous exposerons synthétiquement les contenus de la doctrine géopolitique douguinienne et nous verrons que si les projets de la BRI s’inscrivent bien dans un renversement de la hiérarchie des puissances à l’échelle globale marqué par une revalorisation de l’« île mondiale » – donc à un balancement au profit de la Terre –, l’initiative pourrait constituer, sur un plan plus culturaliste, une submersion du continent par la Mer.

Les fondamentaux de la géopolitique d’Alexandre Douguine : la dialectique Terre-Mer revisitée par la « pensée de la Tradition »

Alexandre Douguine s’inscrit dans une filiation géopolitique a priori classique, à la suite de Ratzel (1882, 1900), Mahan (1892), Castex (1935), Mackinder (1904), Spykman (1944), puisqu’il reprend la récurrente opposition Terre-Mer : « La civilisation thalassique, anglo-saxonne […] serait irréductiblement opposée à la civilisation continentale, russe-eurasienne »19, et le cœur de leur affrontement serait le contrôle du Rimland20. Il a surtout hérité des conceptions allemandes, adoptant un prisme foncièrement culturaliste21 : Il associe comme intrinsèques à la civilisation thalassique les attributs de « protestante, d’esprit capitaliste » tandis que la civilisation continentale serait « orthodoxe et musulmane, d’esprit socialiste ». Il figure parmi les tenants d’une approche plutôt déterministe de cette dichotomie, prise non seulement comme clé de compréhension de la politique au niveau global mais aussi comme véritable « explication de l’histoire ». C’est là toute l’originalité de notre auteur, puisqu’il établit un parallélisme entre cette dichotomie, devenue classique en géopolitique, et la dialectique Tradition-Modernité.

Ce second couple conceptuel n’est pas appréhendé selon ses présentations dans la littérature anthropologique ou sociologique, mais entendu selon l’acception originale portée par une école parfois qualifiée de « pensée de la Tradition »22 qui présente des catégories de pensée très éloignées de celles que l’on rencontre habituellement dans le monde académique contemporain et déployée à la suite de l’œuvre du Français René Guénon. La Tradition renvoie chez ces auteurs « traditionistes »23 à une « Sagesse Éternelle » (Sophia Perennis), une connaissance sacrée, immuable et transcendante transmise aux hommes depuis l’origine de l’humanité. Cette Tradition connaîtrait cependant nécessairement un processus d’obscurcissement à travers les âges (afin que toutes les possibilités de l’Être se manifestent, même les plus inférieures), l’avènement du monde moderne correspondant selon eux à la dernière étape de cette dégradation, une ère chaotique précédent la résorption du monde dans l’incréé – ce que l’on retrouve dans les traditions spirituelles comme étant la « fin des temps ». Pour de tels auteurs, la politique ou l’histoire n’ont de sens qu’en tant qu’elles révèlent l’incarnation de principes métaphysiques – ou archétypes – c’est pourquoi nous évoquions en introduction les termes de métapolitique24 et de métahistoire.

Douguine reprend ces conceptions et s’inscrit parmi ces auteurs traditionistes : Chez lui, la puissance maritime « atlantiste » représenterait les forces de dissolution entraînant le monde moderne vers le chaos, tandis que l’Eurasie aurait pour vocation d’être le bastion de la Tradition, le katechon paulinien25 résistant à la venue des Temps. Ainsi dans son œuvre « l’eschatologie se mêle à la géopolitique », puisqu’il la déploie à partir de postulats visant à se positionner politiquement en fonction des fins dernières de l’homme et des entités politiques. Ce prisme métaphysique l’amène à étudier la politique, l’histoire ou la géographie seulement à travers les principes supérieurs qu’elles incarnent. La Russie et les puissances eurasiatiques deviennent l’incarnation de l’archétype structurant « Terre » (Béhémoth), représentant la Tradition, tandis que les stratégies des États-Unis et de leurs alliés sont lues comme faisant le jeu de l’archétype dissolvant « Mer » (Léviathan), associé aux idéologies modernes. Depuis ces postulats, Douguine propose de « constituer un grand bloc continental eurasien » (versant géopolitique) qui se veut « une force intégratrice, un esprit de renaissance »26 (versant eschatologique) en vue d’édifier un modèle multipolaire pour le système international.

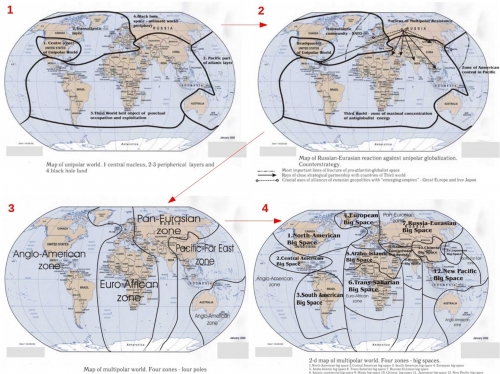

Afin de réaliser cette ambition il propose dès les années 1990, en tant qu’« impératif stratégique majeur » pour la Russie, d’intégrer les pays de la CEI dans une Union Eurasienne fédéraliste : « une seule formation stratégique, unie par une seule volonté et par un seul but de civilisation commune »27. À partir de cette base, il appelle cette entité eurasienne à se rapprocher de ses « partenaires naturels » car en situation de « complémentarité symétrique » avec la Russie : UE, Japon, Iran, Inde. Ceux-ci pourraient devenir de véritable « sujets » des Relations internationales et de la mondialisation s’ils participaient à la sortie du système uni-polaire américano-centré (dans lequel ils n’en seraient que des « objets ») pour construire ensemble la multipolarité. Leur partenariat avec la Russie serait pour Douguine gagnant-gagnant, un renforcement mutuel, étant donné qu’ils ont chacun des éléments vitaux à échanger. D’autres formations géopolitiques intéressées par la multipolarité seraient ensuite encouragées à appuyer ce projet de ré-agencement du système international : Chine, Pakistan, pays arabes… alors que le Tiers-Monde serait plutôt partagé en zones d’influence pour des champions régionaux (le Pacifique constituerait la zone d’influence nippone, l’ Afrique la zone d’influence européenne… ici aussi on retrouve l’influence de l’école géopolitique allemande et des pan-ideen de Haushofer). La thalassocratie étasunienne serait quant à elle refoulée dans l’espace américain (sa zone d’influence naturelle). Ainsi aurait-on des entités géopolitiques puissantes avec leurs zones d’influences propres et un certain équilibre entre les pôles. Cet équilibre multipolaire permettrait alors à la puissance tellurique de laisser se redéployer la Tradition.

La question que nous poursuivons ici est de savoir si la BRI serait pour Douguine un vecteur potentiel pour ses propositions. Participe-t-elle de l’élan vers la « multipolarité traditionnelle » qu’il appelle de ses vœux ? Voyons alors quels élément dans les projets des nouvelles routes de la soie peuvent être décryptés comme participants des ambitions telluriques néo-eurasistes de réagencement du système international dont nous connaissons maintenant les fondamentaux.

La BRI, facteur d’intégration eurasiatique dans le cadre d’une redistribution globale des cartes de la puissance : quelle compatibilité avec le projet multipolaire néo-eurasiste ?

Vers la multi-polarisation

De prime abord, on peut considérer la BRI comme s’inscrivant dans une stratégie d’émancipation de l’uni-polarité américano-centrée. Comme évoqué en introduction, la BRI vise à développer des lignes de communication routières, ferroviaires et maritimes pour relier la Chine à l’Europe et à l’Afrique orientale, via l’Asie Centrale, le Caucase, la Russie, l’Iran, la Turquie… Couplée avec les initiatives menées dans l’OCS et l’UEE, l’initiative s’imbrique donc dans une stratégie générale d’intégration du Rimland avec la masse eurasiatique29, passant outre les instances multilatérales et les canaux de communications ouverts et normés par les États-Unis.

Ces ambitions pourraient donc bien conduire à la définition de normes non-américaines ou non-occidentales30. On le voit par exemple dans le système d’institutions financières élaboré pour financer les projets de la BRI : Banque asiatique d’investissements pour les infrastructures, Fonds Routes de la soie, Nouvelle banque de développement des BRICS, associés à un appel aux fonds souverains des États impliqués dans le projet et aux banques commerciales, les projets se financeraient hors de l’orbite de la Banque mondiale (présidée depuis 1944 par un Américain) et du Fonds monétaire international, symboles de la domination internationale des normes américaines.

Vers la re-continentalisation

L’économie mondiale est à l’heure actuelle essentiellement dépendante des flux maritimes. Cette maritimisation des flux a conduit à une littoralisation des activités de production et donc de la démographie mondiale. En effet, puisqu’il faut exporter via les ports, les entreprises se sont rapprochées des côtes, entraînant alors des mouvements de population à la recherche d’emplois. La BRI, en faisant la part belle aux tracés terrestres, pourrait participer d’une re-continentalisation des supports logistiques de l’économie mondiale et, ce faisant, d’une re-continentalisation de ses pôles de productions.

C’est notamment le vecteur ferroviaire qui semble le plus porteur, grâce à une capacité d’emport supérieure et un coût inférieur de 80 % au transport aérien, pour des échanges deux fois plus rapide que par voie maritime31. Si 7500 conteneurs ont transité sur des trains intercontinentaux en 2012, l’objectif est de porter ce nombre à 7.500.000 pour 2020. Pour profiter de ces flux logistiques, de grandes entreprises telles Hewlett Packard ou Ford se sont déjà délocalisées depuis les côtes chinoises vers l’intérieur des terres pour se positionner sur ces lignes de trains prometteuses32.

Compatibilité de la BRI avec le projet néo-eurasiste : Multipolarité et continentalité ne suffisent pas, l’aspect culturel demeure le plus important

Ces dimensions, « terrestre » et multipolaire, semblent faire entrer la BRI en résonance avec les ambitions du projet néo-eurasiste d’Alexandre Douguine. À l’occasion du Belt and Road Forum de mai 2017, Vladimir Poutine a pu adopter la rhétorique néo-eurasiste en affirmant que grâce à des «formats d’intégration tels que la CEEA, l’OBOR, l’OCS et l’ASEAN, nous pouvons bâtir les bases d’un partenariat eurasien plus vaste» offrant une «occasion unique de créer un cadre de coopération commun qui va de l’Atlantique jusqu’au Pacifique, pour la première fois dans l’histoire». Il ajoute «La Grande Eurasie n’est pas un arrangement géopolitique abstrait, mais, sans exagération, un projet à l’échelle civilisationnelle, tourné vers l’avenir.»33.

Pour autant, même si la BRI renforçait l’organisation multipolaire du système international, et à supposer que la Chine laissera une place à la Russie dans ce nouvel ordre malgré l’asymétrie de leur relation, cela ne toucherait pas l’essence du projet néo-eurasiste. Car, au vu de ce que nous avons esquissé plus haut concernant la pensée traditionnelle, dans la philosophie archétypale douguinienne ce n’est pas la forme qui importe mais le fond, l’esprit. Aussi sa critique de l’uni-polarité thalassocratique ne concerne pas tant la maritimisation de l’économie mondiale que l’esprit maritime qui uniformiserait le monde. C’est pourquoi même si on assistait au reflux de la thalassocratie américaine par la multi-polarisation du système international et à une re-continentalisation de l’économie et de la démographie, une maritimisation culturelle du continent pourrait avoir lieu (un changement du « morphotype » sans modification du « psychotype »).

Cet esprit maritime est caractérisé par Carl Schmitt, l’une des racines intellectuelles d’Alexandre Douguine, qui veut montrer (selon Alain de Benoist, préfaçant la dernière édition de Terre et Mer de Schmitt) la relation logique entre la vie maritime et le libre-échangisme, le capitalisme, le libéralisme, l’individualisme, le parlementarisme, le droit-de-l’hommisme, le constitutionnalisme34… De plus, la « société liquide » (Bauman, 2000) trans-nationaliste créée par la civilisation océanique marchande amènerait peu à peu au délitement du politique, à l’enfoncement dans le fluctuant, le mouvant, le nomade, le réticulaire, le transitoire, à la fragmentation des identités et des sociétés dans l’homogénéité des flots35. Ce sont ces caractéristiques qui sont accolées chez Douguine à la thalassocratie et à la modernité. Le combat eurasiste ne serait donc pas gagné si cette mentalité continuait de s’imposer aux esprits. La multipolarité sans le souffle de la Tradition et la verticalité de la Terre ne serait pas plus souhaitable pour le néo-eurasiste que le système actuel.

Or la BRI est imprégnée à un certain niveau par cette mentalité moderniste : esprit marchand, capitalistique, libre-échangiste et faisant une large place aux marchés financiers ; réticulation de l’espace eurasien, recherche de la vitesse, du mouvement transfrontalier plutôt que de l’ancrage (les marchandises, les capitaux, les travailleurs seront amenés à migrer) ; le tout étant porté par une Chine maoïste, et donc héritière des idées révolutionnaires de 1789, athée, technocratique, pragmatique.

Bien évidemment, les dimensions libérales et constitutionnalistes qui termineraient de caractériser l’esprit maritime sont absentes. Nous sommes essentiellement face dans l’espace eurasien à des puissances (semi-)autoritaires, des démocratures (Max Liniger-Goumaz, 1992) pour qui la souveraineté, le politique, l’Ordre et l’identité (caractéristiques telluriques) sont encore des valeurs importantes (c’est pourquoi Douguine accorde une certaine dimension « traditionnelle » à l’idéologie socialiste, pourtant moderne36). Néanmoins, si l’on suit les auteurs de tendance contre-révolutionnaire, l’esprit moderne-maritime s’est imposé en Occident parce qu’une caste marchande transnationale a pu se constituer et se renforcer jusqu’à s’imposer politiquement pour ensuite dissoudre peu à peu cet ordre politique. Aussi la BRI pourrait-elle donc être l’ouverture nécessaire à la constitution d’une telle caste dans l’espace eurasiatique qui viendrait à terme renverser les valeurs telluriques prônés par Douguine.

Conclusion

Nous avons eu pour but dans cette étude de caractériser le projet des nouvelles routes de la soie au regard de la dialectique Terre-Mer « pérennialiste » d’Alexandre Douguine, qui peut être prise comme un croisement des pensées de Carl Schmitt et de René Guénon. La question était donc de savoir si ces projets constituaient une opportunité pour l’acheminement vers un système international multipolaire accompagné d’une réaffirmation des principes telluriques traditionnels dans l’ordre international – une « domination culturelle » de Béhémoth – ou au contraire s’ils favorisaient l’ouverture vers une diffusion de la mentalité thalassique et moderniste à tout l’espace eurasiatique – le « triomphe » de Léviathan.

Nous avons vu que la coopération stratégique sino-russe autour de la BRI, dans l’hypothèse où la Chine maintiendrait un partenariat équitable envers la Russie, pourrait conduire à une multi-polarisation du système international, avec un continent eurasiatique autonome vis-à-vis de la thalassocratie étasunienne, ce qui constitue le premier versant (géopolitique) du projet néo-eurasiste d’Alexandre Douguine. Cependant, si l’on considère les choses en profondeur et d’un point de vue culturel, l’initiative pourrait porter les germes de l’esprit moderne-maritime qu’il pourfend, le versant eschatologique de son projet serait alors condamné. En vue de constituer ce front de la Tradition37 qu’il appelle de ses vœux, son combat pour l’hégémonie culturelle ne s’arrêterait pas là, il lui faudra encore proposer un modèle permettant d’intégrer les tendances marchandes modernes dans un ordre tellurique politique traditionnel à l’échelle continentale et de maintenir les ancrages identitaires des peuples eurasiatiques.

Ainsi, au regard des fondamentaux de la vision douguinienne, nous pensons que les projets de la BRI pourraient caractériser une véritable croisée des chemins pour les Relations internationales : En effet, l’initiative porte en elle l’opportunité de voir se réaffirmer un ordre du monde basé sur des principes différents de ceux de la mentalité moderne occidentale, tout en comportant le risque de voir cette mentalité se diffuser rapidement au sein du « cœur du monde ». Au-delà même de la perspective eschatologique supportée par Douguine, nous pouvons y voir un réel enjeu en matière de diversité culturelle mondiale : la tension entre différentialisme et uniformisation, représentée chez Schmitt ou Douguine par le combat entre Béhémoth et le Léviathan (la Terre et la Mer au plan non plus géographique mais presque purement mental), est bien réelle !

***

Au delà de cette étude particulière, l’influence de Douguine sur la politique mérite selon nous d’être questionnée et étudiée, cet auteur connaissant une visibilité certaine tant en Russie que dans certaines mouvances idéologiques ouest-européennes. Cependant, si son discours géopolitique rencontre un certain écho et peut emporter l’adhésion parmi les élites russes, l’aspect « gnostique » de ses théories reste bien plus marginal (car estimé irrationnel, idéaliste, hors des critères de la pensée moderne, ou incompris, de par sa difficulté d’accès pour le grand public). Aussi est-il probable que si en apparence le néo-eurasisme et la politique étrangère russe convergent, le dessein recherché soit tout autre : D’un côté nous aurions une politique étrangère réaliste, somme toute moderne bien que conservatrice mais utilisant par opportunité la rhétorique néo-eurasiste, de l’autre une vision traditionnelle métaphysique dont les ambitions ne sont portées que par une minorité restreinte. Nous pensons toutefois que des études politologiques sur l’influence de sa pensée dans le champ des idées et des mouvements politiques serait pertinentes.

Sur un plan plus théorique, une étude conceptuelle sérieuse du couple Tradition-Modernité, confronté avec la réalité empirique, pourrait également offrir selon nous une clé herméneutique intéressante pour la discipline géopolitique, cette dialectique entendue dans son sens guénonien renvoyant à des double-mouvements (différenciation-uniformisation, conservatisme-progressisme, ancrage-nomadisme…) que l’on peut retrouver au cœur de la plupart des rivalités de puissance dans l’espace mondial.

Notes:

1 En chinois, le programme s’intitule Yidai yilu, « Une ceinture, une route » (« One Belt One Road », OBOR). En anglais, l’expression officiellement utilisée par Pékin est toutefois Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

2 Pour une présentation synthétique du projet, voir notamment : LASSERRE Frédéric et MOTTET Eric, « L’initiative Belt and Road, stratégie chinoise du Grand Jeu ? », Diplomatie, numéro 90, 2018/1, pp. 36-40.

3 Visible sur : « First Chinese Train Arrives in Tehran to Revive Silk Road », Strategic Demands Online, 15 février 2016. URL: https://strategicdemands.com/eurasia-newsilkroad/

4 Voir « 21e sommet Chine Union Européenne: vers plus de connectivité ! », OBOReurope, 11 avril 2019.

URL: https://www.oboreurope.com/fr/21e-sommet-chine-union-euro...,consulté le 11 avril 2019.

5 Ont déjà été signés des memorandums ou accords d’intégration entre la RPC et le Luxembourg, l’Italie, la Grèce, le Portugal, mais aussi la Lettonie, la Croatie, la Bulgarie ou Monaco. La Deutsche Bahn s’implique aussi financièrement, notamment par des investissement sur la principale ligne ferroviaire Pologne-Chine Voir « Qu’est que l’accord entre la Chine et l’Italie ? », OBOReurope, 24 mars 2019 (URL : https://www.oboreurope.com/fr/accord-chine-italie/, consulté le 11 avril 2019) et CLAIRET Sophie, « Pourquoi l’Europe risque de se perdre sur les nouvelles routes de la soie ? », GeoSophie, 6 janvier 2017 (URL : https://geosophie.eu/2017/02/05/pourquoi-leurope-risque-d..., consulté le 8 avril 2019).

6 MACKINDER Halford, « The Geographical Pivot of History », The Geographical Journal, vol. 23, 1904/4, pp. 421-437, p. 437 pour ces propos.

7 Voir BOULEGUE Mathieu, « La « lune de miel » sino-russe face à l’(incompatible) interaction entre l’Union Economique Eurasienne et la Belt & Road Initiative », Diploweb, 15 octobre 2017.

URL : https://www.diploweb.com/La-lune-de-miel-sino-russe-face-... consulté le 9 avril 2019.

8 Voir ALEXEEVA Olga, « Le partenariat stratégique Chine-Russie : une alliance durable ? », Areion 24 news, 25 janvier 2019.

URL : https://www.areion24.news/2019/01/25/le-partenariat-strat... consulté le 9 avril 2019.

9 Voir « La route polaire et l’initiative Belt and Road », OBOReurope, 7 novembre 2017 (URL: https://www.oboreurope.com/fr/route-polaire/, consulté le 10 avril 2019). Voir aussi BRUNEAU Michel, L’Eurasie. Continent, empire, idéologie ou projet, Paris, CNRS éditions, 2018, pp. 294-295.

10 Laquelle a une réalité géopolitique conséquente : elle vise à faire coopérer politiquement des pays représentants 2.758.000.000 d’habitants, 38% des approvisionnements en gaz naturel, 20% du pétrole, 40% du charbon et 50% de l’uranium disponibles sur la planète. Voir DUPUY Emmanuel, « Les nouvelles Routes de la Soie et l’Asie Centrale : l’Organisation de Coopération de Shanghai (OCS) en première ligne… », La Vigie, 16 novembre 2017 (URL : https://www.lettrevigie.com/blog/2017/11/16/les-nouvelles..., consulté le 4 avril 2019)

11 BOUCHARD Renaud et PORFIRYEV Boris, « L’économie russe et le basculement géostratégique », conférence donné dans le cadre du séminaire Franco-Russe « L’intégration eurasiatique en perspective / Евразийская интеграция в перспективе », Paris, EHESS, 14 septembre 2016 – 16 septembre 2016. URL : http://renaudbouchard.canalblog.com/archives/2016/09/22/3..., consulté le 6 avril 2019.

12 L’expression néo-eurasisme distingue ces auteurs du mouvement d’idées qualifié d’eurasisme classique, héritier du mouvement slavophile du XIXème siècle et qui finira par se rapprocher de la « révolution conservatrice » allemande. Pour l’histoire intellectuelle de ces mouvements, voir notamment : MEAUX (de) Lorraine, La Russie et la tentation de l’Orient, Paris, Fayard, 2010, 436 pages ; DRESSLER Wanda (dir.), Eurasie : espace mythique ou réalité en construction ?, Bruxelles, 2009, Bruylant, 410 pages (particulièrement pp. 49-68 et 95-106) ; SEDGWICK Mark, Contre le Monde Moderne. Le traditionalisme et l’histoire intellectuelle secrète du XXème siècle, Paris, Dervy, 2008, 380 pages (particulièrement pp/ 287 et ss.).

13 LARUELLE Marlène, « Le néo-eurasisme russe. L’empire après l’empire ? », Cahiers du monde russe [En ligne], 42/1, 2001, mis en ligne le 01 janvier 2007, pp. 71-94.URL: https://journals.openedition.org/monderusse/8437#bodyftn2, consulté le 5 avril 2019.

14 Philosophe, géopoliticien, écrivain et militant politique, né le 7 janvier 1962 à Moscou.

15 Par ses théories et son apparence physique, Alexandre Douguine est régulièrement qualifié de « Raspoutine », de « conseiller occulte du Kremlin », nourrissant des analyses assez éloignées de la réalité de son influence et parfois teintées d’un esprit « complotiste ».

16 Le concept d’hégémonie culturelle a été pensé par Antonio Gramsci, qui a décrit comment une classe dominante faisait aussi reposer son pouvoir sur une domination culturelle, à travers des outils tels que l’école ou les médias. Il s’agit alors pour les forces d’opposition de conquérir les esprits en diffusant au maximum leurs idéologies avant de pouvoir renverser le rapport de domination (préalable sans lequel le nouveau pouvoir ne saurait être accepté par la population), d’où la formule utilisée de « bataille gramscienne ».

17 MOHAMMEDI Adlène, « Le « néo-eurasisme » d’Alexandre Douguine : une revanche de la géographie sur l’histoire ? », Philitt, 4 juillet 2016. URL : https://philitt.fr/2016/07/04/le-neo-eurasisme-dalexandre... , consulté le 4 avril 2019.

18 Photographie publiée en ligne sur le site Geopolitica.ru. URL : https://www.geopolitica.ru

19 Le Prophète de l’Eurasisme. Alexandre Douguine, Paris, Avatar Éditions, 2006, pp. 16.

20 Définit par Spykman comme « une région intermédiaire située […] entre le Heartland (cœur du monde) et les mers périphériques […] vaste zone tampon de conflits entre la puissance maritime et la puissance terrestre. Orientée des deux côtés, elle doit fonctionner de manière amphibie et se défendre aussi bien sur terre qu’en mer », car « Celui qui domine le Rimland domine l’Eurasie ; celui qui domine l’Eurasie tient le destin du monde entre ses mains ». Voir SPYKMAN Nicolas, The Geography of the Peace, New York, Harcourt, Brace and Co, 1944, p. 43.

21 La dialectique Terre-Mer est appréhendée dans la littérature géopolitique de façon plus ou moins pragmatique – conception surtout présente chez les Anglo-saxons – ou plus ou moins culturaliste – appréhension plutôt rencontrée chez les auteurs Allemands.

22 Formulation retenue par Christophe Boutin, voir BOUTIN Christophe, Politique et tradition. Julius Evola dans le siècle (1898-1974), Paris, Éditions Kimé, 1992, 513 pages ; Id., « Tradition et réaction : la figure de Julius Evola », In., « Les pensées réactionnaires », Mil neuf cent, n°9, 1991, pp. 81-97.

23 Néologisme proposé par le philosophe Pierre Riffard pour éviter les confusions avec le terme de « traditionalistes », utilisé aussi pour parler de courants politiques ou religieux réactionnaires. Voir : RIFFARD Pierre, L’Ésotérisme, Paris, Robert Laffont, 2003 (1990), 1032 pages. On rencontre parfois le terme « pérennialistes », bien qu’il vise plutôt la frange du mouvement développée sur le continent nord-américain. Voir HOUMAN Setareh, De la Philosophia Perennis au pérennialisme américain, Milan, Archè, 2010, 622 pages.

24 Le mot métapolitique est « à celui de politique ce que le mot métaphysique est à celui de physique […] la métaphysique de la politique » (MAISTRE Joseph (de), Considérations sur la France suivi de l’Essai sur le principe générateur des constitutions, Bruxelles, 2006 (1797), Éditions Complexe, p. 227), et vise à donner à une philosophie politique un fondement d’universalité par la référence à une vérité transcendante, le but étant d’orienter l’être et la société vers cette sphère, de traduire cette transcendance dans la réalité sociale en réfléchissant à l’organisation idéale de la Cité. Sous cette acception, le concept est à distinguer tant de la théologie politique (qui est le transfert de concepts théologiques dans le processus de construction de l’État) que du conservatisme (car il ne se réfère pas au passé mais à la métaphysique immuable, éternelle, supra-temporelle) ou de l’intégrisme (car il ne se réfère pas à une tradition spirituelle particularisée, mais à une Vérité absolue devant être supérieure à ces traditions). Voir BISSON David, René Guénon. Une politique de l’esprit, Paris, Pierre Guillaume de Roux, 2013, 527 pages, pp. 130 et s., qui utilise le triptyque infra-politique, politique, méta-politique comme clé méthodologique pour analyser l’impact de l’œuvre de Guénon.

25 Entité évoqué par l’apôtre saint Paul, le katechon est un être dont la nature n’est pas précisée et qui a pour vocation d’empêcher la venue de l’Antéchrist. Ce dernier ne peut se manifester pleinement tant que cette entité est dans le monde Voir dans la Bible les versets : 2 Thes. 2, 6-7.

26 Le Prophète de l’Eurasisme, op. cit, p. 19.

27 Ibid., p. 29.

28 Visible sur le site du mouvement EVRAZIA : http://evrazia.org/modules.php?name=News&file=article.... La carte 1 représente le monde unipolaire actuelle, la 2 la contre-stratégie que doit déployer la Russie pour briser l’uni-polarité, la 3 révèle les futures grandes zones d’influence souhaitées par le projet néo-eurasiste et la 4 les « grands espaces » géopolitiques au sein de ces zones.

29 STRUYE DE SWIELANDE Tanguy, « La Chine et ses objectifs géopolitiques à l’aube de 2049 », in « Regards géopolitiques », Bulletin du Conseil québécois d’études géopolitiques, volume 2, n°1, printemps 2016, pp. 24-28.

30 GARCIN Thierry, « Le chantier – très géopolitique – des Routes de la soie », Diploweb, 18 février 2018.

URL : https://www.diploweb.com/Le-chantier-tres-geopolitique-de..., consulté le 10 avril 2019.

31 LASSERRE Frédéric et MOTTET Eric, « L’initiative Belt and Road, stratégie chinoise du Grand Jeu ? », op. cit.

32 FRANKOPAN Peter, Les Routes de la Soie. L’histoire du cœur du monde, Bruxelles, Éditions Nevicata, 2017, p. 622.

33 ESCOBAR Pepe, « Vladimir Poutine s’aligne avec Xi Jinping pour élaborer un nouvel ordre mondial (commercial) », RTFrance, 17 mai 2017.

URL : https://francais.rt.com/opinions/38470-vladimir-poutine-a..., consulté le 9 avril 2019.

34 Voir SCHMITT Carl, Terre et Mer (1942), Paris, Pierre Guillaume de Roux, 2017, p. 63.

35 Ibid., p. 66-67.

36 De toute manière, selon les postulats métaphysiques retenus par les auteurs comme Douguine, il n’existe aucun étant « pur » : tout ce qui est manifesté est constitué d’un dosage entre les différentes polarités. Concrètement, il ne peut exister d’entité entièrement tellurique ou entièrement thalassique.

37 En référence à l’ouvrage : DOUGUINE Alexandre, Pour le Front de la Tradition, Nantes, Ars Magna, 2017.

BIBLIOGRAPHIE

Ouvrages

––, Le Prophète de l’Eurasisme. Alexandre Douguine, Paris, Avatar Éditions, 2006, 349 p.

BISSON David, René Guénon. Une politique de l’esprit, Paris, Pierre Guillaume de Roux, 2013, 527 pages

BRUNEAU Michel, L’Eurasie. Continent, empire, idéologie ou projet, Paris, CNRS éditions, 2018, 352 pages.

BOUTIN Christophe, Politique et tradition. Julius Evola dans le siècle (1898-1974), Paris, Éditions Kimé, 1992, 513 pages

DRESSLER Wanda (dir.), Eurasie : espace mythique ou réalité en construction ?, Bruxelles, 2009, Bruylant, 410 pages.

FRANKOPAN Peter, Les Routes de la Soie. L’histoire du cœur du monde, Bruxelles, Éditions Nevicata, 2017, 732 pages.

HOUMAN Setareh, De la Philosophia Perennis au pérennialisme américain, Milan, Archè, 2010, 622 pages.

MAISTRE Joseph (de), Considérations sur la France suivi de l’Essai sur le principe générateur des constitutions, 2006 (1797), Éditions Complexe

MEAUX (de) Lorraine, La Russie et la tentation de l’Orient, Paris, Fayard, 2010, 436 pages.

RIFFARD Pierre, L’Ésotérisme, Paris, Robert Laffont, 2003 (1990), 1032 pages.

SCHMITT Carl, Terre et Mer (1942), Paris, Pierre Guillaume de Roux, 2017, 240 pages.

SEDGWICK Mark, Contre le Monde Moderne. Le traditionalisme et l’histoire intellectuelle secrète du XXème siècle, Paris, Dervy, 2008, 380 pages.

SPYKMAN Nicolas, The Geography of the Peace, New York, Harcourt, Brace and Co, 1944, 66 pages.

Articles

BOUTIN Christophe, « Tradition et réaction : la figure de Julius Evola », in., « Les pensées réactionnaires », Mil neuf cent, n°9, 1991, pp. 81-97.

LASSERRE Frédéric et MOTTET Eric, « L’initiative Belt and Road, stratégie chinoise du Grand Jeu ? », Diplomatie, numéro 90, 2018/1, pp. 36-40.

MACKINDER Halford, « The Geographical Pivot of History », The Geographical Journal, vol. 23, 1904/4, pp. 421-437.

STRUYE DE SWIELANDE Tanguy, « La Chine et ses objectifs géopolitiques à l’aube de 2049 », in « Regards géopolitiques », Bulletin du Conseil québécois d’études géopolitiques, volume 2, n°1, printemps 2016, pp. 24-28.

Articles en ligne

ALEXEEVA Olga, « Le partenariat stratégique Chine-Russie : une alliance durable ? », Areion 24 news, 25 janvier 2019.URL : https://www.areion24.news/2019/01/25/le-partenariat-strat...

BOUCHARD Renaud et PORFIRYEV Boris, « L’économie russe et le basculement géostratégique », conférence donné dans le cadre du séminaire Franco-Russe « L’intégration eurasiatique en perspective / Евразийская интеграция в перспективе », Paris, EHESS, 14 septembre 2016 – 16 septembre 2016. http://renaudbouchard.canalblog.com/archives/2016/09/22/3...

BOULEGUE Mathieu, « La « lune de miel » sino-russe face à l’(incompatible) interaction entre l’Union Economique Eurasienne et la Belt & Road Initiative », Diploweb, 15 octobre 2017 https://www.diploweb.com/La-lune-de-miel-sino-russe-face-...

CLAIRET Sophie, « Pourquoi l’Europe risque de se perdre sur les nouvelles routes de la soie ? », GeoSophie, 6 janvier 2017.URL : https://geosophie.eu/2017/02/05/pourquoi-leurope-risque-d...

DUPUY Emmanuel, « Les nouvelles Routes de la Soie et l’Asie Centrale : l’Organisation de Coopération de Shanghai (OCS) en première ligne… », La Vigie, 16 novembre 2017 URL : https://www.lettrevigie.com/blog/2017/11/16/les-nouvelles...

ESCOBAR Pepe, « Vladimir Poutine s’aligne avec Xi Jinping pour élaborer un nouvel ordre mondial (commercial) », RTFrance, 17 mai 2017.URL : https://francais.rt.com/opinions/38470-vladimir-poutine-a...

GARCIN Thierry, « Le chantier – très géopolitique – des Routes de la soie », Diploweb, 18 février 2018. URL : https://www.diploweb.com/Le-chantier-tres-geopolitique-de...

LARUELLE Marlène, « Le néo-eurasisme russe. L’empire après l’empire ? », Cahiers du monde russe [En ligne], 42/1, 2001, mis en ligne le 01 janvier 2007, pp. 71-94. https://journals.openedition.org/monderusse/8437#bodyftn2

MOHAMMEDI Adlène, « Le « néo-eurasisme » d’Alexandre Douguine : une revanche de la géographie sur l’histoire ? », Philitt, 4 juillet 2016.https://philitt.fr/2016/07/04/le-neo-eurasisme-dalexandre...

« 21e sommet Chine Union Européenne: vers plus de connectivité ! », OBOReurope, 11 avril 2019.

URL: https://www.oboreurope.com/fr/21e-sommet-chine-union-euro...

« La route polaire et l’initiative Belt and Road », OBOReurope, 7 novembre 2017.URL: https://www.oboreurope.com/fr/route-polaire/

« Qu’est que l’accord entre la Chine et l’Italie ? », OBOReurope, 24 mars 2019 https://www.oboreurope.com/fr/accord-chine-italie/

Cartes

BOUCHARD Renaud et PORFIRYEV Boris, « L’économie russe et le basculement géostratégique », conférence donné dans le cadre du séminaire Franco-Russe « L’intégration eurasiatique en perspective / Евразийская интеграция в перспективе », Paris, EHESS, 14 septembre 2016 – 16 septembre 2016.http://renaudbouchard.canalblog.com/archives/2016/09/22/3...

« First Chinese Train Arrives in Tehran to Revive Silk Road », Strategic Demands Online, 15 février 2016 URL: https://strategicdemands.com/eurasia-newsilkroad/

« Les nouvelles routes de la soie : le cauchemar de Brzezinski passe par l’Asie centrale », Investig’action, 10 octobre 2018.

URL : https://www.investigaction.net/fr/les-nouvelles-routes-de...

Sitographie

Site Geopolitica.ru. URL : https://www.geopolitica.ru

Site du mouvement EVRAZIA : http://evrazia.org/modules.php?name=News&file=article....

00:50 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Eurasisme, Géopolitique, Nouvelle Droite | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : nouvelle droite, alexandre douguine, nouvelle droite russe, routes de la soie, eurasisme, eurasie, europe, affaires européennes, asie, affaires asiatiques, politique internationale, géopolitique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Algorithmic Governance and Political Legitimacy

Algorithmic Governance and Political Legitimacy

00:30 Publié dans Philosophie, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, philosophie politique, matthew b. crawford, gouvernance algorithmique, surveillance, théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Europe : Orban contre Macron ou souverainistes contre globalistes

Europe : Orban contre Macron ou souverainistes contre globalistes

En vue des élections européennes de 2019

L’émergence conservatrice en Europe et la politique des identités

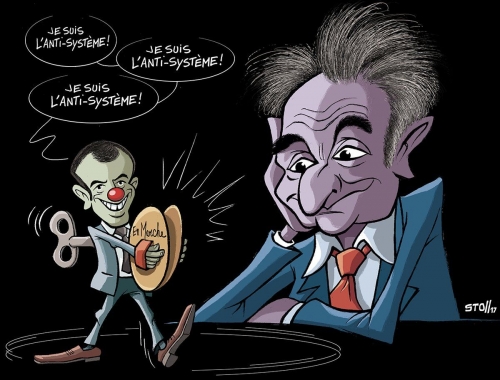

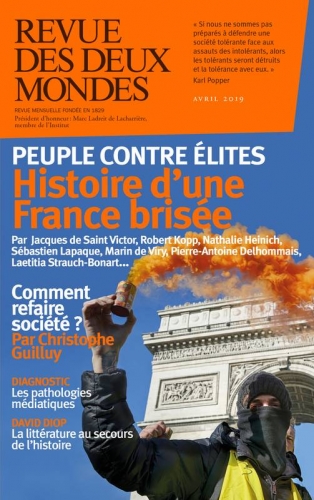

L’évolution de la conjoncture européenne en vue des élections parlementaires de 2019 résulte d’une opposition entre dirigeants européens et américains à propos des deux notions, du « peuple » et du « gouvernement », se présentant comme une opposition entre populistes et élitistes, ou encore entre « nationalistes » et « globalistes », « souverainistes illibéraux » (Orban, Salvini et autres) et « libéraux anti-démocratiques », tels Macron, Merkel et Sanchez.

Cette opposition reprend la classification de Yascha Mounk, Professeur à Harvard,dans son essai, « Le peuple contre la Démocratie« , qui explique pourquoi le libéralisme et la démocratie sont aujourd’hui en plein divorce et pourquoi on assiste à la montée des populismes.

La crise de la démocratie libérale s’explique, selon Mounk, par la conjonction de plusieurs tendances, la dérive technocratique du fait politique, dont le paroxisme est représenté par l’Union Européenne, la manipulation à grande échelle des médias et une immigration sans repères qui détruit les cohésions nationales.

Ainsi l’atonie des démocraties exalte les nationalismes et les formes de « patriotisme inclusif », qui creusent un fossé entre deux conceptions du « peuple », celle défendue par Trump, Orban et les souverainistes européens, classifiés comme « illibéraux démocratiques » et celle des « libéraux anti- démocratiques »,pour qui les processus électoraux sont contournés par les bureaucraties, la magistrature (en particulier la Cour Suprême aux États-Unis) et les médias, dans le buts de disqualifier leurs adversaires et éviter les choix incertains des électeurs.

Ce type de libéralisme permet d’atteindre des objectifs anti-populaires par des méthodes détournées.

Or, dans la phase actuelle, la politique est de retour en Europe, après une longue dépolitisation de celle-ci, témoignée par le livre de F. Fukuyama, qui vient de paraître aux États-Unis, au titre: « Identité: la demande de dignité et la politique du ressentiment« .

Fukuyama nous expliquait en 1992, que « la fin de l’histoire » était la fin du débat politique, comme achèvement du débat entre projets antagonistes, libéralisme et socialisme, désormais sans objet.

Au crépuscule de la guerre froide, il reprenait au fond la thèse de Jean Monnet du début de la construction européenne sur la « stratégie de substitution » de la politique pour atteindre l’objectif de l’unité européenne.

Une stratégie qui s’est révélée une « stratégie d’occultation » des enjeux du processus unitaire et de lente dérive des nouveaux détenteurs du pouvoir, les »élites technocratiques », éloignées des demandes sociales et indifférentes, voire opposées au « peuple ».

Pour Fukuyama l’approfondissement de sa thèse sur la démocratie libérale comme aboutissement du libéralisme économique, implique encore davantage aujourd’hui, après trente ans de globalisation, un choix identitaire et un image du modèle de société, conçue en termes individualistes, d’appartenance sexuelle, religieuse et ethnique.

Le contre choc de la globalisation entraîne un besoin d’appartenance et une politique des identités, qui montrent très clairement les limites de la dépolitisation.

Les identités de Fukuyama sont « inclusives », car elles réclament l’attachement des individus aux valeurs et institutions communes de l’Occident, à caractère universel.

Face à l’essor des mouvements populistes, se réclamant d’appartenances nationales tenaces, les vieilles illusions des fonctionnalistes, pères théoriques des institutions européennes, tels Haas, Deutsch et autres, selon lesquelles la gestion conciliatrice des désaccords remplacerait les conflits politiques et l’efficacité des normes et de la structure normative se substitueraient aux oppositions d’intérêts nationaux, est remise radicalement en cause, à l’échelle européenne et internationale, par les crises récentes de l’Union.

En effet, la fragilité de l’euro-zone, les politiques migratoires, les relations euro-américaines et euro- russes révèlent une liaison profonde, conceptuelle et stratégique, entre politique interne et politique étrangère.

Elles révèlent l’existence de deux champs politiques,qui traversent les différences nationales et opposent deux conceptions de la démocratie et deux modèles de société, celle des « progressistes (autoproclamés) » et celle des souverainistes (vulgairement appelés populistes).

« L‘illibéralisme » d’Orban contre le »le libéralisme anti-démocratique » de Macron

Ainsi l’enjeu des élections européennes de mai 2019 implique une lecture appropriée des variables d’opinions,le rejet ou l’aquiescence pour la question migratoire, l’anti-mondialisme et le contrôle des frontières.

Cet enjeu traduit politiquement une émergence conservatrice, qui fait du débat politique un choix passionnel, délivré de tout corset gestionnaire ou rationnel

Ce même enjeu est susceptible de transformer les élections de 2019 en un référendum populaire sur l’immigration et le multi-culturalisme, car ce nouveau conservatisme, débarrassé du chantage humanitaire, a comme fondement l’insécurité, le terrorisme et le trafic de drogue, qui se sont installés partout sur le vieux continent.

Il a pour raison d’être l’intérêt du peuple à demeurer lui même et pousse les dirigeants européens à promouvoir une politique de civilisation.Il n’est pas qui ne voit que le phénomène migratoire pose ouvertement la question de la transformation démographique du continent et, plus en profondeur,la survie de l’homme blanc,

En perspective et par manque d’alternatives, l’instinct de conservation pourra mobiliser tôt ou tard les peuples européens vers un affrontement radical et vers la pente fatale de la guerre civile et de la révolte armée contre l’islam et le radicalisme islamique

Ainsi autour de ces enjeux, le débat entre les deux camps, de « l’illibéralisme » ou de l’État illibéral à la Orban et du « libéralisme sans démocratie » à la Macron, creuse un fossé sociétal dans nos pays, détruit les fondements de la construction européenne et remet à l’ordre du jour le mot d’ordre de révolution ou d’insurrection.

Il en résulte une définition de l’Europe qui, au delà du Brexit, n’a plus rien à voir avec le marché unique ou avec ses institutions sclérosées et désincarnées, mais avec des réalités vivantes, ayant une relation organique avec ses nations.

Les élections parlementaires de 2019 constitueront non seulement un tournant, mais aussi une rupture avec soixante ans d’illusions européistes et mettront en cause le primat de la Cour européenne des droits de l’homme, censée ériger le droit et le gouvernement des juges au dessus de la politique.

Ainsi le principe de l’équilibre des pouvoirs devra être redéfini et le rapport entre formes d’État et formes de régimes, revu dans la pratique, car mesuré aux impératifs d’une conjoncture inédite.

Le fossé entre élites et peuple doit être ré-évalué à la mesure des pratiques des libertés et à l’ostracisation du discours des oppositions, classé « ad libitum » comme phobique ou haineux, ignorant les limites constitutionnelles du pouvoir et de l’État de droit classiques.

Or la conception illibérale de l’État, dont s’est réclamé Orban en 2014, apparaît comme une alternative interne à l’équilibre traditionnel des pouvoirs et , à l’extérieur, comme une révision de la politique étrangère et donc comme la chance d’une « autre gouvernance » de l’Union, dont le pivot serait désormais la nation, seul juge du bien commun.

Or la conception illibérale de l’État, dont s’est réclamé Orban en 2014, apparaît comme une alternative interne à l’équilibre traditionnel des pouvoirs et , à l’extérieur, comme une révision de la politique étrangère et donc comme la chance d’une « autre gouvernance » de l’Union, dont le pivot serait désormais la nation, seul juge du bien commun.

Cette conception de » l’État non libéral, ne fait pas de l’idéologie l’élément central de l’organisation de de l’État, mais ne nie pas les valeurs fondamentales du libéralisme comme la liberté ».

En conclusion « l’illibéralisme d’Orban »résulte d’une culture politique qui disqualifie, en son principe, la vision du libéralisme constitutionnel à base individualiste et fait du « demos » l’axe portant de toute politique du pouvoir.

Le débat entre « souverainistes » et « progressistes » est une preuve de la prise de conscience collective de la gravité de la conjoncture et de l’urgence de trancher dans le vif et avec cohérence sur l’ensemble de ces questions vitales.

En France le bonapartisme est la quintessence et la clef de compréhension de l’illibéralisme français, qui repose sur « le culte de l’État rationalisateur et la mise en scène du peuple un ».

Orban réalise ainsi la synthèse politique de Poutine et de Carl Schmitt, une étrangeté constitutive entre « la verticale du pouvoir » du premier et du concept de souveraineté du second, qui s’exprime dans la nation et la tradition et guère dans l’individu.

Cette synthèse fait tomber « un rideau du doute » entre les deux Europes, de l’Est et de l’Ouest, tout au long de la ligne du vieux « rideau de fer », allant désormais de Stettin à Varsovie, puis de Bratislava à Budapest et, in fine de Vienne à Rome.

D’un côté nous avons le libre-échange sauvage, la morale libertine et une islamisation croissante de la société, sous protection normative de l’U.E et de certains États-membres, de l’autre les « illibéraux » de l’Est, qui se battent pour préserver l’héritage de l’Église et de la chrétienneté.

L’espace passionnel de l’Europe centrale, avec, en fers de lance la Pologne et la Hongrie puise dans des « gisements mémoriels », riches en histoire, les sources d’un combat souverainiste et conservateur, qui oppose à l’Ouest deux résistances fortes, culturelles et politiques.

Sur le plan culturel une résistance déclarée à toutes les doctrines aboutissant à la dissolution de la famille, de la morale et des mœurs traditionnelles (avortement et théorie du genre).

Sur le plan politique, la remise en question du clivage droite-gauche, la limitation des contre- pouvoirs, affaiblissant l’autorité de l’exécutif et au plan général, la préservation des deux héritages, la tradition et l’histoire, qui protègent l’individu de la contrainte, quelle qu’en soit la source, l’État, la société ou l’Église; protection garantie par une Loi fondamentale à l’image de la Magna Carta en Grand Bretagne (1215), ou de la Constitution américaine de 1787.

Cette opposition de conceptions, de principes et de mœurs, aiguisés par la mondialisation et la question migratoire, constitueront le terrain de combat et de conflit des élections européennes du mois de mai 2019 et feront de l’incertitude la reine de toutes les batailles, car elles seront un moment important pour la création d’un nouvel ordre en Europe et, indirectement, dans le monde.

00:27 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : emmanuel macron, viktor orban, france, hongrie, europe, affaires européennes, illibéralisme, néolibéralisme, union européenne |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Il Kairós

Massimo Selis

Ex: http://www.ilpensieroforte.it

«There is a crack, a crack in everything / That's how the light gets in (Vi è una crepa, una crepa in ogni cosa / È così che la luce entra)» cantava Leonard Cohen in Anthem.

L’arco di questo ultimo scorcio di modernità, nella fattispecie, la sua esternazione tecnologica, ha finito la sua corsa. La curva che si distendeva ampia fino a qualche decennio fa, ora si stringe chiudendo verso i bracci. Rigettato tutto ciò che avesse anche solo un’ombra sbiadita della millenaria Tradizione che ci precede, essa ha regalato agli uomini un nuovo credo costruito su facili slogan: libertà, progresso, democrazia, e altri simili. Dalle macerie della guerra essa si è innalzata esibendosi maestosa fino alla fine dello scorso secolo. Ma gli acciacchi della vecchiaia si facevano intravedere; ora però sono divenute metastasi di un corpo decadente.

Il tempo della Storia, infatti, non si sviluppa in modo differente da quello di ogni uomo, che nasce, cresce, si sviluppa e solidifica durante l’età adulta, fino a scivolare nella vecchiaia che conduce alla morte. Così i cicli, così le ere e i regni. Lo svolgersi lineare e indefinito del tempo lungo gli eoni è abbaglio per gli sciocchi e gli insipienti.

Le crepe si stanno aprendo sempre più ampie e prepotenti: crisi economica, scontri sociali e ideologici, conflitti, eventi catastrofici. La sofferenza e la tragicità esprimono il volto esteriore, ma il male, suo malgrado, lavora sempre anche per un risveglio del bene: queste sciagure possono essere anche, in fondo, una benedizione per chi ha occhi per vedere. La facciata posticcia e illusoria della modernità sta cadendo a pezzi, lasciando intravedere fra le sue crepe, una nuova strada, l’ingresso nella Nuova Umanità redenta.

«È giunto il momento di riconoscere i segni dei tempi, di coglierne le opportunità e guardare lontano». Se rettamente intese, queste parole di Giovanni XXIII a pochi giorni dal suo beato transito, sono un monito e un indirizzamento. Eppure proprio qui sorgono tutti i limiti e le paure dell’uomo moderno, anche di quei pochi che oggi non si arrendono alla dittatura del pensiero unico.

Il primo di questi è per l’appunto, il non saper leggere i segni, perché in fondo ad essi non crediamo affatto. Invero, ogni cosa nell’Universo Creato è segno, o per meglio dire, simbolo, di qualcos’altro. Questa è certezza di ogni Sapienza Tradizionale, anche e soprattutto di quella cristiana. La Storia, d’altro canto non è semplice successione di eventi, bensì Storia Sacra che si svolge dall’alfa all’omega secondo un superiore disegno di Provvidenza. Pertanto all’uomo il cui intelletto non è ancora stato sigillato non possono sfuggire i segni che continuamente essa ci presenta. Solo un’opera di cultura può colmare tale ignoranza e portare ad un primo risveglio dei sensi interiori.

Il primo di questi è per l’appunto, il non saper leggere i segni, perché in fondo ad essi non crediamo affatto. Invero, ogni cosa nell’Universo Creato è segno, o per meglio dire, simbolo, di qualcos’altro. Questa è certezza di ogni Sapienza Tradizionale, anche e soprattutto di quella cristiana. La Storia, d’altro canto non è semplice successione di eventi, bensì Storia Sacra che si svolge dall’alfa all’omega secondo un superiore disegno di Provvidenza. Pertanto all’uomo il cui intelletto non è ancora stato sigillato non possono sfuggire i segni che continuamente essa ci presenta. Solo un’opera di cultura può colmare tale ignoranza e portare ad un primo risveglio dei sensi interiori.

Tuttavia, pur avendo compreso in quale tragico punto della navigazione cosmica ci troviamo, occorre passare all’azione per il tempo che ci verrà concesso, poco o tanto che sia. Per fare ciò dobbiamo passare dalla cecità dell’Io alla lucidità del Noi. L’individualismo liberista sembra aver vinto per il momento, bisogna ammetterlo. Dobbiamo allora comprendere che nulla è possibile senza la comunione di liberi spiriti, comunione che è molto più che semplice comunità. Il singolo non può nulla nella bolgia modernista. Solo all’interno di una civiltà si è potuto creare in passato cultura e bellezza. Solo nella comunione ci si può prendere cura della vocazione di ognuno.

Creare, per l’appunto. Oggi si assiste a timidi e spesso solo moralistici tentativi di opposizione, gesti difensivi e nulla più. Ma l’uomo ha la dignità che gli spetta solo quando crea. Le gemme dell’intelletto come i capolavori dell’arte nascono dalla forza misteriosa che spinge verso quell’ordine celeste dal quale tutti fummo generati: uomini e cosmo. La bellezza non può nascere dalla paura, ma solo dalla sapiente speranza!

Secondo una tradizione, la capacità mantica dell’oracolo delfico derivava dalle esalazioni provenienti da una spaccatura nel terreno. Questo è il tempo in cui fumi di luce promanano dal cadavere della modernità: occorre leggerne il significato profetico. Questo è il tempo in cui bisogna vincere la schiavitù delle consuetudini e divenire umili servitori della Verità. Questo è il tempo in cui un manipolo di uomini liberi è chiamato a creare con fedele spirito cavalleresco quel poco di Giustizia e Bellezza che renderà meno dura la caduta di “questo mondo” e preparerà quello a venire. Questa è l’ora, il kairós, e non può essere disattesa.

00:05 Publié dans Philosophie, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, tradition, temps, kairos, mythologie, mythologie grecque, antiquité grecque, grèce antique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

In The Black Box Society: The Hidden Algorithms That Control Money and Information, University of Maryland law professor Frank Pasquale elaborates in great detail what others have called “platform capitalism,” emphasizing its one-way mirror quality. Increasingly, every aspect of our

In The Black Box Society: The Hidden Algorithms That Control Money and Information, University of Maryland law professor Frank Pasquale elaborates in great detail what others have called “platform capitalism,” emphasizing its one-way mirror quality. Increasingly, every aspect of our

First, in the spirit of Václav Havel we might entertain the idea that the institutional workings of political correctness need to be shrouded in peremptory and opaque administrative mechanisms because its power lies precisely in the gap between what people actually think and what one is expected to say. It is in this gap that one has the experience of humiliation, of staying silent, and that is how power is exercised.

First, in the spirit of Václav Havel we might entertain the idea that the institutional workings of political correctness need to be shrouded in peremptory and opaque administrative mechanisms because its power lies precisely in the gap between what people actually think and what one is expected to say. It is in this gap that one has the experience of humiliation, of staying silent, and that is how power is exercised.